Cultural Sensitivity in Health Care Delivery and Research

The final morning session featured four speakers who examined in greater detail the influence of culture in determining health inequities. Roger Dale Walker, professor in the departments of psychiatry, public health, and preventive medicine at the Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU), described a mentoring program designed to recruit and retain Native Americans and Alaska Natives (ANs) in health care delivery and biomedical research. Terry Maresca, medical director for the Snoqualmie tribe and clinical associate professor in the department of family medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine, listed a number of programs that can serve as models for increasing the number of culturally aware clinicians and researchers. Benjamin Young, former dean of students at the University of Hawaii School of Medicine, described his extremely successful efforts to increase the number of Native health care practitioners in Hawaii and the Pacific Islands. Finally, Arne Vainio, a family practice physician at the Min-No-Aya-Win Human Services Clinic on the Fond du Lac Ojibwe Reservation in Cloquet, Minnesota, discussed how important it can be for practitioners to share the culture of the communities they serve.

A MENTORING PROGRAM FOR NATIVE STUDENTS

The One Sky Center is a national resource center for all American Indian (AI) communities in North America, said Roger Dale Walker, OHSU. It also is a resource center for policy makers in the federal government and elsewhere, because to make good decisions about Native Americans, policy makers need to know Native Americans. The center, which operates out of

the office of the president at OHSU, does research, recruits Native Americans to medicine and research, works to retain Native Americans in medical training, provides training and technical assistance for clinicians and community workers, and conducts other programs aimed at the intersection of Native Americans with medicine and biomedical research. It also maintains a listing of more than 100 programs that are doing excellent work across Indian communities but often do not get the visibility they deserve.

Every site is different, said Walker. The One Sky Center works at more than 50 different sites in a year, which means that people working with the center need to absorb a history and a culture every time they go to a new community, whether it is inner-city, rural, or high-poverty.

Walker focused in his presentation on a national model for mentorship to attract and retain Native Americans and ANs in health care delivery and biomedical research. The model is complicated by the diversity of places where AIs live. Today, two-thirds of Indians live off a reservation, which means that their lives and health care are influenced not only by the federal government but also by states, counties, and cities. Mentorship also is complicated by the high rate of attrition among Native American students. Half of the Native Americans who enter college leave in the first year, according to the National Institute for Leadership in Higher Education. Only 3 of every 20 Native Americans who enter college graduate. “That is a hard place to find Ph.D. candidates,” he stated.

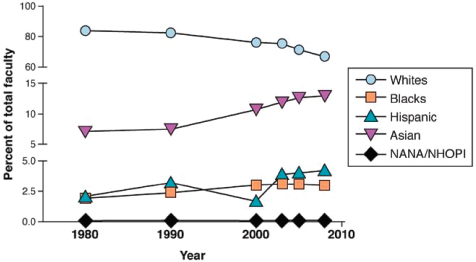

Having a critical mass of other Native American students and mentors is a major problem. Association of American Medical Colleges data from 2008 show that there is a total of only 14 Native American professors in the United States, said Walker, and “we need to do something about that” (see Figure 4-1).

The mentorship program at OHSU is designed to increase that number substantially. Among its goals are the following:

• Provide instruction on conducting research.

• Provide insight into Native identity, both at the personal and community levels.

• Improve trainees’ self-confidence.

• Critique and support trainees’ research.

• Assist in defining and achieving career goals.

• Socialize trainees into the profession.

• Assist in the development of collegial networks.

• Advise how to balance work and personal life.

• Assist in the development of future colleagues.

Native peoples have unique struggles in college, said Walker. They have to preserve their home lives while embracing a life of research. Trainees have to be socialized not just on Indian issues but also on institutional and

FIGURE 4-1 The percentage of Native American and Native Alaskan faculty members in degree-granting institutions remains very low.

NOTE: NANA = Native American/Native Alaskan; NHOPI = Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander.

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics, 2010.

research issues. Many Native Americans come back home after being in college and are told that they have changed. “There are some real conflicts that we need to think about,” he explained.

The program currently has 17 Native mentors from across the United States, all at the associate professor level or higher. These mentors are serving 27 mentees, about half of whom are in premedical programs or in medical schools, with the other half in doctoral or postdoctoral programs. It is a tight-knit community that encourages multiple types of mentorship contact, including

Face to Face

• Attend national and regional conferences as mentor/mentee teams.

• Discuss career objectives and strategies to accomplish those objectives.

• Co-present at conferences.

• Have lunch or share breaks at meetings.

• Alerts of programs and new information.

• Answers for mentees of quick questions.

• Reminders about programs and other activities.

Phone

• Set up strategy meetings and touch base (especially when tone of voice is important and e-mail will not suffice).

Internet

• Reference materials, data links, and news.

• Job search information and recruitment.

• Communication through Facebook.

Mentors and mentees discuss research methods, proposals, and grant management. They attend scientific conferences with Native researchers and go to meetings on Native or community themes and policies, along with workshops designed specifically for mentees. The program holds an annual conference and focused workshops and has prepared individuals for national leadership roles. The relationships formed through the program are ongoing and go on indefinitely, because American Indians will continue to face difficult issues throughout their careers. Recently, the program has begun working with high school students to increase the number of students entering the pipeline in college. Students can work with anyone in the network who has the expertise they need.

Walker emphasized the need to increase interactions between Native people and national leaders. “People who are leaders and non-Native need to know Natives,” he said, and “people who are Native need to know who these leaders are and begin to make outreach happen.”

The program has already had many successes, including new faculty members, admissions to graduate school, postdoctoral fellowships, grants in preparation, funded grants, and numerous publications and presentations. Furthermore, it has ambitious future plans, including

• Recruit new mentees each year.

• Further refine the mentor role and recruit new mentors.

• Recruit new senior non-Native researchers as associates.

• Continue to develop relationships with the Indian Health Service (IHS) and professional health organizations.

• Develop a National University Consortium for Native Health Research.

• Apply for a National Mentoring Network Grant.

“We are very excited about trying to make this a movement and to expand our richness as broadly as we can,” Walker concluded.

Many Native Americans come back home after being in college and are told that they have changed. “There are some real conflicts that we need to think about.” —Roger Dale Walker

INCREASING THE NUMBER OF CULTURALLY AWARE CLINICIANS AND RESEARCHERS

Terry Maresca, University of Washington School of Medicine, discussed five broad approaches to increasing the number of culturally aware clinicians and researchers. The first is increasing cultural safety for patients and students. As models, Maresca cited several programs:

• A program on the Crow Reservation in Montana pairs tribal elders as teachers with new clinicians in reservation settings, allowing providers who are new to the community to have a safe person with whom to talk. In dealing with issues such as birth, serious illness, or impending death, the community becomes the expert rather than the medical or nursing director.

• In the Rural Human Services Program at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, elders-in-residence conduct onsite and distance learning with health care professionals, including behavioral health aides, who are serving Native villages. Having elders involved is especially important when dealing with sensitive issues such as chemical dependency, violence, or suicide, said Maresca.

• The Snoqualmie tribe in Washington and the Southcentral Foundation in Alaska have planted Native herbal medicine gardens on clinic property. Such programs have the effect of reconnecting Native peoples with the land. In addition, a program at Northwest Indian College in Bellingham, Washington, promotes the use of traditional plants, particularly for diabetes prevention, with the community as the driving force behind the program. The program is now being expanded to address issues of access to indigenous foods, which has sparked interest among tribes that have not been able to access areas where they can gather, hunt, or fish.

• The University of Washington has held an annual summit that brings together the university president and top staff with 29 leaders of the tribes in the state to discuss the barriers to postsecondary recruitment and retention for Native students. In the future, said Maresca, university officials would be even better served by going into tribal communities to have these conversations.

The second area Maresca discussed is the need to learn respect for indigenous healing practices, again using several examples as models:

• The Association of American Indian Physicians, a small group with less than 400 members that has been in existence for more than four decades, holds a cross-cultural medicine workshop that brings in indigenous healers from around the country to conduct a dialogue about Native health practices with students, clinicians, and other interested community members.

• The IHS holds an annual conference titled Advances in Indian Health designed to enhance awareness of disparities, the role of historical trauma, and cultural healing practices. Such programs help to address the reluctance of some parts of the health system to understand the health benefits traditional practices can produce.

• The Puyallup Tribal Health Authority in Washington conducts cultural in-service training for all staff. Such programs should not just be “helicopter training,” said Maresca, but fully developed programs that work with communities to understand how to address disparities with the resources that are available.

• The Seattle Indian Health Board Family Medicine Residency Program, which was established in 1994, has been collaborating with traditional healers to conduct clinical training embedded in Native communities. More than three-quarters of the graduates of the program remain in underserved communities.

• The University of Washington has established rural training sites with a connection to Native communities for 6-month immersion training of medical students.

The third set of programs Maresca described are aimed at modifying work to fit the available workforce:

• A program for dental health aide therapists in Alaska is designed to meet the needs of rural Native villages. Therapists receive 2 years of training and do not require a dental college degree, which has generated controversy with the American Dental Association.1

• A parallel program in California is taking the same approach with urban Native communities, which have equally high oral health disparities.

______________

1The American Dental Association opposes the dental health aide therapist (DHAT) program because the organization believes that the training received in the DHAT program is inadequate for performing the surgical procedures typically performed by licensed dentists.

• Jobs to Careers, a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation partnership with the IHS, Northern Arizona University, and the Winslow Indian Health Care Center, supports medical technologists as entry-level health care workers, with students receiving college credit for work.

• Southcentral Foundation in Alaska has an internship program starting in high school that pays students to work in all divisions of the health system, including traditional healing and administration, with cultural values training to serve “customer-owners.”

• Through a partnership with the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, high school students from Alaska are able to remain in the state and participate in a biomedical research summer program that centers on alcohol and health.

Increasing the number of Native clinicians and researchers requires wider and more welcoming pathways into health professions schools. Programs that have been making a difference include the following:

• Since 1973, the Indians into Medicine program at the University of South Dakota has supported a robust pipeline program in a five-state region with a large AI population. A holistic admissions program has contributed to the program’s success, as has a cultural diversity tuition waver.

• For two decades the University of Washington and the University of Minnesota have sponsored programs called Indian Health Pathways that feature a specific curriculum, including a research requirement, a traditional Native medicine clerkship, and mentoring. Several participants at the Institute of Medicine (IOM) workshop had completed one of these programs.

• Another consortium, called Pathways to Health, has brought together more than 150 tribes, AI/AN organizations, tribal colleges, universities, the IHS, federal agencies, area health education centers, and state health departments. The initiative offers cultural attunement, interprofessional training, and distance learning.

Finally, in the area of promoting culturally aware faculty and research, Maresca highlighted the following programs:

• The University of Washington, the University of Minnesota, and other institutions serve as Native American Centers of Excellence to provide faculty development fellowships and seminars.

• The University of Colorado Native Investigator Development Program and Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health provide intensive mentoring for Native researchers and clinicians to transition to research on elder health disparities.

• The Mayo Clinic Spirit of Eagles program promotes Native researchers, scientists, and medical students who are involved in cancer control activities in Native communities.

• The National American Research Centers for Health supports partnerships between tribes or tribally based organizations for research on Native health issues and faculty development.

• The Center for Native Health Partnerships at Montana State University creates community-based participatory research links with all seven tribes in the state and supports the student pipeline.

Maresca concluded by showing a photograph of a Native University of Washington graduate who, after training in rural Oregon and spending time with the Native health system there, chose to return to her home in northern California to practice medicine. “That is success for me,” she said.

In-service sessions should not be “helicopter training,” but fully developed programs that work with communities to understand how to address disparities with the resources that are available. —Terry Maresca

INCREASING THE NUMBER OF NATIVE PRACTITIONERS IN HAWAII AND THE PACIFIC ISLANDS

In 1972, Benjamin Young, who had just finished his residency, received a note from Terence Rogers, the dean of the University of Hawaii School of Medicine. At that time, Young was the first Native Hawaiian to go into the field of psychiatry, and he was 1 of fewer than 10 Native Hawaiian physicians licensed in the state of Hawaii. Rogers told Young that he wanted him to recruit more Pacific Islanders into the field of medicine.

Working throughout the Pacific was a great challenge, Young said. The islands of the Pacific are separated by huge distances and have different languages, cultures, and educational systems. At the time, there were no Pacific Islander physicians in Micronesia, and there was just one Samoan doctor, a surgeon in American Samoa.

Young began by working to develop a 1-year intensive review of biology, chemistry, mathematics, and physics to bring the MCAT scores of

Native students up to acceptable levels. Starting such a program required curricula, classrooms, and students. Young recruited students by talking with teachers, appearing at schools, and going on talk shows. He got essential support from a number of people, including the late U.S. senator Daniel Inouye, who was “a key person to know, especially for Native Americans.”

Since Young began working on the problem, more than 350 Native Hawaiian physicians have graduated from the University of Hawaii School of Medicine and are in practice throughout the islands. Key leadership positions in Hawaii, including director of health for the state of Hawaii, the chairs of several departments in the university, and directors of community health centers, are products of the program, Young stated. The program has also produced 6 physicians for the Northern Marianas, 17 for Guam, 4 for Palau, 1 for Yap, and 12 for American Samoa. All returned to their islands, and several are in leadership positions, further encouraging students to enter medicine.

During much of this period, Young was director of the Native Hawaiian Center of Excellence at the School of Medicine, which seeks to recruit and retain Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in medicine and the health professions. He also was dean of students for almost 15 years and shared in both the triumphs and the struggles of the students he helped recruit.

“In 1972, the dean told me, ‘Let’s increase the numbers of Pacific Islanders, including Hawaiians, in medicine.’ Today, in 2012, we can look back with no small amount of pride that we did what we said we were going to do,” Young concluded.

“In 1972, the dean told me, ‘Let’s increase the numbers of Pacific Islanders, including Hawaiians, in medicine.’ Today, in 2012, we can look back with no small amount of pride that we did what we said we were going to do.” —Benjamin Young

WEAVING CULTURE INTO THE CLINICAL SETTING

Providers who grew up in the same culture as the people they are helping can make a huge difference to individuals and to communities, said Arne Vainio, Min-No-Aya-Win Human Services Clinic. Vainio is in great demand as a physician in his communities because he understands what people go through. When he was a young doctor, he tried to maintain a professional distance, but maintaining that distance turned out to be impossible. “I am part of the community,” he said.

Vainio also emphasized the importance of keeping Native languages and cultures alive to encourage more Native students to become health care providers. He explained that “there is an Ojibwa language table that we go to, my family and I … that is a really special thing.”

Vainio writes a monthly column for News from Indian Country, in which he has written about diseases and about “the strength and the beauty that come with people.” He tells people in his community that writing about them is the best way to pass on their teachings. “That is a sacred obligation,” he said, as Native Americans historically have not had a written culture or historical documents that say who they are. Instead, stories are passed down through the elders from one generation to the next.

Vainio also has written about his own experiences with medicine, although, he said, “you can’t find a worse patient than a middle-aged Native man, unless you make him a doctor.” Recently, a filmmaker suggested making a documentary about Vainio’s experiences and put him and his wife in touch with a graphic arts student from the University of Minnesota, Duluth. For 2 years Vainio worked and traveled accompanied by a film camera, he recalled, “in case I said something profound.” The documentary that resulted is called Walking into the Unknown. At the workshop, Vainio ran a short segment from the film, in which he talked about suicide among his family members and among his people.

Vainio concluded by explaining that “this is dark stuff that people don’t talk about. It is difficult to bring up these conversations. These are scary conversations, but it is important…. When you have those kinds of demons, you either hide them in the closet, so they haunt your dreams, or you open the doors and you let the sunlight get them. That is what I have chosen to do.”

“It is difficult to bring up these conversations. These are scary conversations, but it is important…. When you have those kinds of demons, you either hide them in the closet, so they haunt your dreams, or you open the doors and you let the sunlight get them. That is what I have chosen to do.” —Arne Vainio

Rosalina James, assistant professor in the department of bioethics and humanities at the University of Washington, asked about how to get Native Americans involved as researchers even when they do not have doctorates, because their knowledge of Native communities and health issues can

be indispensable for research to succeed. Maresca said it was a powerful question and that she could immediately picture individuals without “initials after their names” who would make major contributions to research. Bridges need to be built to access the knowledge and skills of these individuals and others who could further research.

Models and examples could demonstrate the potential of tapping into a community’s infrastructure, after which such initiatives could expand. As an example, Young described a $4.6 million endowment grant to the University of Hawaii to establish a research center to encourage young researchers to participate in projects on health conditions that are prominent in Native communities such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

Walker pointed to the importance of grant writing in the funding process. Grants are awarded with the expectation of outcomes, and these outcomes need to be carefully defined around the needs of a community. Many people in Indian country have tremendous experience and continue to learn more all the time. “We need to find a mechanism to recognize that,” he said, and some programs are beginning to succeed in finding ways to tap into this expertise.

Other ways to foster community-based research will be available through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, said Eve Higginbotham, Emory School of Medicine. Such research will be able to examine the economic drivers that are pushing health care to become more value-based and outcomes-driven.

Lisa Thomas, research scientist at the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington, pointed to a project funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, the Healing of the Canoe, which has community partners who are co-investigators on the project. In the eighth year of the partnership, the research skills of the community partners were “up to par” with those of the university researchers. However, longer grants may be needed for community partners to build the capacity to be fully prepared partners.

This page intentionally left blank.