Cancer Prevention and Treatment in Native Communities

Cancer has been a silent disease for Native communities, said Jennie Joe, director of Native American research and training and professor in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, who moderated the panel on cancer prevention at the workshop. Many Native communities did not even have a name for the disease, and indigenous cultures did not have experience diagnosing or treating it. This situation is starting to change, she said, partly because cancer has become a critical problem in Native communities. In particular, community-level groups are implementing innovative approaches to prevention, early diagnosis, and effective treatment that are useful and effective.

Three speakers covered programs in cancer prevention and treatment. JoAnn Tsark, project director at ‘Imi Hale Native Hawaiian Cancer Network, described a program to train both clinical cancer patient navigators and community cancer patient navigators in the Hawaiian Islands. A comprehensive cancer control program was the subject of the talk by Kerri Lopez, director of Northwest Tribal Cancer and Western Tribal Diabetes Projects with the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board. Linda Burhansstipanov, president and grants director of the Native American Cancer Research Corporation, shared some of the lessons she has learned in tailoring cancer prevention and survivorship programs for local communities.

A CANCER PATIENT NAVIGATION TRAINING PROGRAM IN HAWAII

Although Native Hawaiians make up about 20 percent of the population in Hawaii, cancer is a cause of death for Native Hawaiians at a rate 50 percent higher than for the state as a whole. In response to this disparity, the ‘Imi Hale Native Hawaiian Cancer Network was established to increase cancer prevention and control in Native Hawaiian communities, cancer prevention and control research, and the number of Native Hawaiian researchers.

JoAnn Tsark described the Ho’okele i ke Ola Navigating to Health program within the ‘Imi Hale network. The program is a community-driven effort to address cancer health disparities in Hawaii by training cancer patient navigators. The health care system is fractured and disjointed in Hawaii, said Tsark, as in the rest of the country. In addition, rates of mammograms and colonoscopies are lower for Native Hawaiians than for other groups, which means the cancers are detected later, are more complicated, and have worse outcomes. Although some islands have sophisticated medical care delivery systems, other islands have fewer oncologists and services. For example, the island of Molokai has no oncologists or radiologists.

The Navigating to Health program involved communities from the start and sought to build on community strengths and values. It promoted co-learning and capacity building and sought to provide tangible benefits, including an increase in the number of people who could access cancer services when needed. It conducted an extensive review of navigator programs elsewhere, held focus groups with cancer survivors and their families on five islands, and consulted with mentors from the National Cancer Institute.

In the process, the program discovered three truths about cancer care, according to Tsark. First, cancer care is complicated and fractured. Even within Hawaii, what Maui patients want is not necessarily what Kauai patients want. Second, regardless of regional preferences, all people need information, access to services, emotional and cultural support, and confidence and assistance to manage their care. Third, all patients face barriers both in the community and in the health care setting. As access barriers, Tsark listed

• high costs,

• no insurance,

• few providers and services,

• long travel distance to care,

• patients too busy to seek care, and

• stressed support systems.

In addition, systems barriers include

• running between different providers for different services,

• lost referrals and paperwork,

• not knowing who is in charge,

• not knowing what to ask,

• feeling intimidated, and

• providers’ lack of sensitivity, time to answer questions, or knowledge of resources.

The ‘Imi Hale patient navigator model is designed to provide navigation through the cancer care continuum. It is training both clinical cancer patient navigators and community cancer patient navigators, because the two categories of navigators need expertise in their different domains. The program identified 14 core competencies:

1. Describe the role of a cancer patient navigator.

2. Explain the importance of maintaining the confidentiality of the people you help.

3. Describe barriers to cancer care and ways to overcome them.

4. Identify unique risk factors, tests, and treatments of cancer.

5. Identify related physical, psychological, and social issues likely to face people with cancer and their families.

6. Demonstrate the ability to gather data and create a “Patient Record.”

7. Demonstrate ability to find reliable cancer information from agencies and on the Web.

8. Describe cancer-related services available in your community.

9. Describe the advantages of participating in clinical trials and barriers to participation.

10. Define palliative care and hospice care.

11. Assist patients in completing an advance directive.

12. Demonstrate the ability to work through “mock” cancer cases.

13. Demonstrate ability to organize a resource binder.

14. Describe ways to care for yourself.

The findings of the review process also shaped the format of the training. Future navigators receive 48 hours of training spread over 2 days per week for 3 weeks. The training was instituted as a three-credit community college class, because college credits were more valuable to the trainees than a certificate. Training incorporated multiple methodologies, including lectures, class activities, onsite tours, role playing, networking, writing, and developing resource binders, with an emphasis on communications, roles and boundaries, and relationships.

The curriculum and materials were developed from scratch to support the navigators, and funding came from a variety of sources, including an initial grant in 2005 from the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. “I’m a believer that if you ask for what you want and you know where you’re going to go, you’re going to get the funds to do it,” said Tsark. Many of the physicians, radiologists, nurses, social workers, and others who were consulted in setting up the program agreed to volunteer for each 6-day session, which helped build relationships among navigators and health care providers. Cancer survivors and previously trained navigators also served as trainers. “It’s not a very expensive program, but it is very much labor-intensive,” she explained.

By 2012 the program had conducted 11 48-hour trainings on four islands and 30 continuing education sessions. It had produced 146 navigators, held 5 annual conferences, and made multiple national presentations. It also had started to expand into screening navigation to enhance prevention. The program established 13 paid positions for community patient navigators and received a grant to put navigators in three rural hospitals. And the majority of graduates had reported using their patient navigation skills in their jobs as community outreach workers and health care providers.

Future goals of the program are to develop navigation programs in more clinical settings, strengthen navigation at both the screening and survivor ends of the cancer spectrum, receive third-party payor support for navigation services, and report and publish outcomes data for the state of Hawaii. “Did we increase the number of navigators? Yes. Did we increase the number of hospitals offering this service? Yes. Did we reduce financial and geographical cultural barriers? Yes. Did we establish it as a reimbursable service? Not yet. But we’re on there,” Tsark concluded.

“I’m a believer that if you ask for what you want and you know where you’re going to go, you’re going to get the funds to do it.” —JoAnn Tsark

A COMPREHENSIVE CANCER CONTROL PROGRAM IN THE NORTHWEST

The Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board was founded in 1973 to serve the 43 federally recognized tribes in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. Its mission is “to assist Northwest tribes to improve the health status and quality of life of members’ tribes and Indian people in their delivery of culturally appropriate and holistic health care.” Kerri Lopez started

working for the board in 1992 and has been involved in tobacco control, women’s health programs, elders’ programs, and seatbelt safety. “I’ve been a part of it for 20 years, so I’ve seen a lot happen,” she said.

In 2002 the Yakama tribe hosted a major meeting on cancer control, which led to funding of the first tribal comprehensive cancer program. A navigator project involving six tribes also began in 2002, along with a survey of behavioral risk factors through the Indian Health Board, which was repeated starting in 2012.

Since 1998 the Northwest Tribal Cancer Coalition has held meetings involving many Northwest tribes and has achieved several important benchmarks, according to Lopez. It performs trainings and has distributed tribal mini-grants for a variety of cancer control activities. It also provides cancer updates for clinicians covering such issues as cancer screening, Native American/Alaska Native cancer policy, cancer patient education, and the use of electronic health records. “For a comprehensive cancer program to actually get primary care providers to a training is a minor miracle, [but] we manage to get about 35 to 40 people at our trainings every year,” she explained.

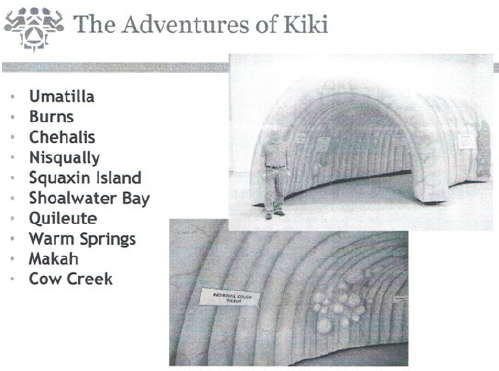

During tribal site visits, the cancer program conducts a Cancer 101 training, helps to develop tribal action plans, and engages in grant writing that has led to the reception of several mini-grants, with follow-up phone and e-mail technical assistance. It also sponsors visits from Kiki, a large, inflatable, walk-through section of a colon that demonstrates the progression from healthy cells to polyps to cancer (see Figure 6-1). “When folks start talking about that to me I was like, eww, that is so not going to go over in Indian country,” said Lopez. But “Kiki’s been a hit. She’s been to all these tribes. She’s gotten folks talking about colorectal cancer screening. There’s education going on.” Furthermore, as Lopez said in response to a question during the discussion session, colon cancer screening numbers have been going up at the Indian Health Service (IHS) clinics.

The Northwest Tribal Comprehensive Control Program has developed a variety of tools and resources, including a Northwest Tribal Cancer Resource Guide, a text for its Cancer 101 training, cancer fact sheets, an appointment companion, and tribal cancer action plans. It also has developed a 20-year Northwest Tribal comprehensive cancer control plan. The program has developed partnerships among the tribes, with state health programs in the Northwest, with foundations and nonprofit organizations, and with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. As just one example, the program has partnered with the Fred Hutchinson Institute in Seattle to interview cancer survivors.

Cancer control and epidemiology in Indian country still need better clinical data and cancer data capacity for electronic health records, Lopez said. Prevention also will remain critical, including youth activities, better

FIGURE 6-1 Kiki, an inflatable walk-through colon, has helped increase colon cancer screening in Native American communities.

SOURCE: Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board.

nutrition, physical activity, tobacco cessation, and wellness in the workplace. And cancer survivors who come back to their tribes need better care, because the clinics offer only ambulatory health care, not cancer care.

The best ideas come from the tribes themselves, Lopez added, providing a partial list of the kinds of activities going on at the tribal level:

• Pap-a-Thon (free pap test and health education for women)

• Pink Paddle Project (canoe trip for female cancer survivors to raise awareness of cancer)

• Aerobics video • Pink Shawl Project (multigenerational breast health awareness project)

• Mother-daughter tea/lunch

• Golf tournaments

• Cancer awareness day

• Cancer 101

• Great American Smoke-Out

• Men’s health day

• Relay on the Rez (cancer fundraising event)

• Cooking classes/healthy eating

• Just Move It (campaign to promote physical activity)

• Tribal Cancer Coalition

• Women and Wellness

• Lifestyle intervention classes

• Breast cancer awareness bingo

• Colorectal cancer poker walk (a walking event where participants draw a card at each of several stations. The best poker hand at the end of the walk is eligible for prizes)

“I want to give credit to my tribes,” she said, “but we could do a lot more with more funding.” —Kerri Lopez

CULTURAL ISSUES IN CANCER PREVENTION AND SURVIVORSHIP

Native communities are well known for their sharing traditions, said Linda Burhansstipanov, Native American Research Corporation. All of the programs and approaches described at the workshop by the workshop speakers are free for others to use. “We don’t believe in hoarding,” she said. “You shouldn’t have to start from scratch on anything.”

But every program needs to be tailored to the local community, because every community is different. In particular, different parts of the United States have statistically significant differences in cancer incidence and mortality. Lung and bronchus cancer incidence rates do not differ much among non-Hispanic white men, but they differ greatly for Native Americans and Alaska Natives, from well above the national average (in Alaska and the Great Plains) to well below (in the East, the Pacific Coast, and especially the Southwest). Using a single number for the cancer rate among Native peoples masks the uniqueness of different regions. “It’s lifestyle. It’s behavioral variation. It’s cultural practices of what you can and cannot eat or what you can and cannot do,” said Burhansstipanov.

Understanding these differences and lowering cancer rates require addressing the barriers to prevention and care in culturally respectful manners, Burhansstipanov continued. Community-driven and community-based participatory research programs are essential. Programs are not necessarily evidence-based unless they are based on evidence from the community in which they will be applied; a program designed for and by one community

will not necessarily translate to another community. And community-based means that budgets should be split equally, instead of the typical structure in which most of the money goes to the researchers and a small portion goes to the community.

No community program is now or ever will be perfect. Community programs evolve, and interventions that work for a while need to change as the community changes. Interventions need to go beyond collecting survey data to have some sort of benefit for the community. “We have been surveyed to death,” said Burhansstipanov. Strategies that work for non-Native communities frequently lack the inherent characteristics that need to be included in Native programs. Also, interventions need to be informed by the community, and particularly by the guidance of elders. “We stand on the shoulders of our ancestors,” said Burhansstipanov.

To be successful, surveys need to integrate traditional, healthy American Indian culture and behaviors, she said. They need to result in improved and culturally acceptable services and programs that survive beyond the length of a grant. Examples of successful interventions include Native patient navigators, stories and vignettes captured from Native peoples, and interactive patient activities.

Everything needs to be evaluated. For example, workshops that involve interactive activities show a 25 percent greater retention rate 3 months later than workshops that lack interactive activity, “so we do not do a community workshop without having an interactive activity,” Burhansstipanov explained. Local leadership and partnerships are essential if an intervention is to be sustainable.

In particular, supplying Native patient navigators “is the most beneficial, interactive, proactive, strategic intervention that we have ever done,” Burhansstipanov said. The best qualification for being a navigator is not education but passion for a community and respect from the community. The navigators even have made it possible to talk openly about cancer, whereas before Native people tended to avoid the subject.

Burhansstipanov’s work on cancer prevention and survivorship has yielded several lessons that she shared at the workshop. Prevention is needed for all people, including cancer survivors. One-third of the survivors in the network are overweight. One-third go back to smoking cigarettes after they have been diagnosed with cancer. Thirty-eight percent of survivors have concurrent diabetes. Also, inequities due to living in poverty are exacerbated in rural areas. And a willingness to undergo screening does not help unless people have access to health care.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) seeks to address these issues in three ways. First, it enrolls people into some sort of insurance. The IHS never has served as insurance, Burhansstipanov observed. It is not funded at a high-enough level. In the network’s database of about

820 survivors, only 12 percent use the IHS for their cancer care. However, the ACA will need Native navigators who can translate policies into action and get people into the appropriate programs.

Second, the ACA will coordinate services in a system that is extremely fragmented today. This will ease the current problem of establishing residency and qualifying for programs, which can be extremely complex, costly, and time-consuming. In local programs today, funding for health care can run out at certain points in the funding cycle, and delays in enrollment and referrals can delay treatment, even for people with advancing cancers.

Third, the ACA emphasizes behavioral interventions. In this regard, it overlaps with responsibilities traditionally allotted to public health.

Burhansstipanov concluded by noting several essential components of community-based participatory research. First, local leadership is essential. Second, the budget must truly be split equally between the researchers and the tribes. Finally, it is critical that researchers spend some time in the communities they are studying.

“We stand on the shoulders of our ancestors.” —Linda Burhansstipanov

This page intentionally left blank.