A Conceptual Model of Aging for the Next Generation of Research

How individuals and societies experience and respond to aging is deeply influenced by the contexts in which that experience occurs. Individual and collective experiences, behaviors, and decisions are shaped by social contexts. Those contexts affect the significance, meaning, and interpretation of the aging experience for individuals as well as communities. Contexts are in turn collectively constituted by individuals. What is it like for an individual to turn 65 when remaining life expectancy is 20 years rather than 10? What are the implications for a society when those defined as “old” are a quarter of the population rather than a tenth?

Myriad changes in family and generational structures, in patterns of employment and retirement, in racial/ethnic composition, and in biological processes affecting longevity and senescence can influence vulnerability and resiliency in the aging population and shape disparities in well-being. Demographic, economic, political, and health-care changes affect the resources available to an aging population, and the resources—in wisdom, services, and accumulated wealth—that aging individuals can provide to others. As Phyllis Moen notes (see Chapter 9), “It is hard but essential for innovative research over the coming decades to study changing lives and changing structures, as well as the links (including mismatches) between the two.”

Grasping the changes in lives, structures, and contexts across the aging process requires conceptual models that can encompass the whole. It also calls for models that can capture heterogeneity, fluidity, and indeterminacy within larger patterns. Hardy and Skirbekk (see Chapter 7) caution,

The traditional measures of population aging implicitly assume homogeneity in the aging process, and temporal comparisons based on these traditional measures assume that the societal implications associated with skills, abilities, functionalities and behaviors linked to chronological age operate in the same way across time. There is ample evidence that neither of these assumptions is correct.

Aging is changing for individuals and societies, the social contexts of aging are changing, the shifts are not homogeneous, and the study of aging is changing as well (see Chapter 1). Clear conceptual models are needed for the next phase of research on aging. Useful models capture current understandings and guide emerging efforts, help to identify gaps in knowledge, suggest synergies among different approaches, and may facilitate transdisciplinary initiatives.

Theorizing and model-building exercises are never complete. New conceptualizations are challenged and refined by empirical findings. Multiple causal pathways and translational mechanisms are suggested by observations, but require further analysis. In the study of aging, priorities for theorizations and conceptualization include how and when contexts impact individual lives, relations, health, and genetic transcription. Concomitant attention is addressing how micro processes within and between individuals generate new macro contexts. These processes occur in a specific time, whether in the life course of an individual or the political and historical trajectory of a community or society, which is also significant to their impact.

An example of ongoing theory building is reviewed by Shanahan (see Chapter 12). Addressing the impact of social context on the individual and the life course, possible models include a critical period, a sensitive period, and a chain of risks. The critical period model posits a definite time during development in which a biological system changes durably in response to the environment; the sensitive period model also posits a specific time span for the period of heightened plasticity, but it views change as possible at other periods as well. The chains of risks model suggests that risks (such as low socioeconomic status) faced in childhood increase the likelihood of subsequent disadvantages, perhaps by increasing the chances that the individual may exhibit vigilance and mistrust of others, diminished self-regulation, and a proclivity for risky behaviors. This constellation of perceptions and behaviors, sometimes called the “defensive phenotype” (Miller, Chen, and Parker, 2011), then increases both exposure to stress and stress reactivity, adversely affecting health and other outcomes. A fourth model, developed by O’Rand (O’Rand and Hamil-Luker, 2005), proposes that early disadvantages initiate strongly path-dependent exposure to risks across the phases of life and that the differences attributable to initial disadvantage are magnified over time (analogous to compound interest) (Diprete and Eirich,

2006). Thus, while the chain of risks model points to the accumulation of risk factors, O’Rand’s model suggests that the effect of early risk is accentuated over time. These different theoretical perspectives present nuanced life course models that address early exposures, durable changes, feedback mechanisms, and late-emerging consequences—all relevant to the experience of aging. The different perspectives may be appropriate to research questions addressing a range of exposures and risks and to designing and evaluating interventions across the life course.

As such questions are examined, the panel proposes a conceptual model to facilitate further theory and research efforts on the ways in which social processes and contexts affect aging. The model can be of use in many different disciplines and in transdisciplinary initiatives in the study of aging.

A CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF AGING

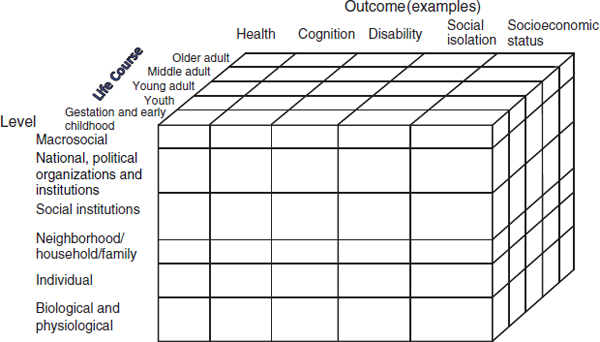

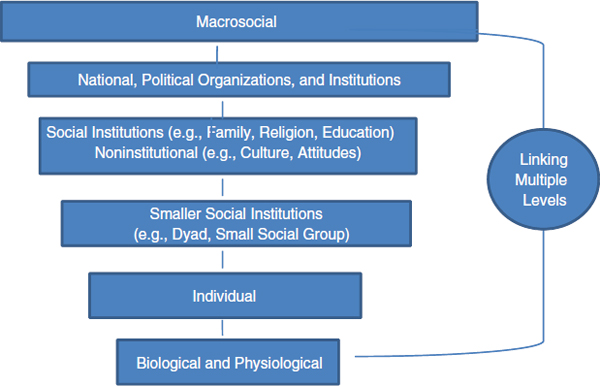

A many-celled cube (see Figure 2-1) illustrates a conceptual model for studying social processes in aging over the life course. The model has three dimensions: (1) levels from macro to subindividual; (2) developmental stages over the life course; and (3) examples of outcomes of interest. The model is based on the work of Silverstein and Giarrusso (2011), who propose a biographical-institutional-societal model of the life course and the deliberations of the panel, particularly regarding the further explication of and connections among the different levels (see Figure 2-2). It is important

FIGURE 2-1 Conceptual model for studying social processes in aging over the life course.

FIGURE 2-2 Changing social processes and social context in an aging society—The conceptual model: how the social sciences see the world.

to note that the model is intended to offer a heuristic for thinking conceptually about the linkages across levels but does not define a hierarchy nor does it present any specifics as to the combination of level, life stage, and outcome.

Each cell of this cube defines a set of topics of potential interest in the study of aging. For example, the cell at the lower left-hand corner of the cube addresses health as the outcome of interest at the biological and physiological level during gestation and childhood. Shanahan (see Chapter 12) describes recent research that falls within this cell. The cell in the upper right-hand corner, in contrast, examines socioeconomic status as the outcome at the macrosocial level during older adulthood. Angel and Settersten (see Chapter 6), Hardy and Skirbekk (see Chapter 7), and Moen (see Chapter 9) all point to important and unanswered questions about aging in this cell.

Levels of Social Organization

As presented in the model, factors at all levels can have an impact on aging. Ascertaining the ways in which social processes and contexts relate to aging, both as causes and consequences, at all levels requires a clear understanding of the social fabric in which individuals are embedded.

Attention to levels includes addressing how individuals belong to and are nested in many layers of social units, from the largest agglomerations of nations and even international patterns; to major social institutions; to neighborhoods, workplaces, and civic or religious organizations; to households, couples, and families; and ultimately to individuals themselves and their physiologies.

The levels are interconnected and the flow of influence between levels is often multidirectional. The family, for example, mediates the effects of macrosocial changes on individuals. The degree to which the family serves this function may be affected by alterations in the family as a social institution, at the same time that the changing family itself contributes to macrosocial change.

Macrosocial (Demography)

At the top of Figure 2-2 are the macrosocial or demographic trends operating at the societal level. Characteristics of the population at any given time are partially defined by population aging. Simultaneously, those characteristics affect how individuals and the society experience and respond to aging. Macrodemographic trends are the consequences of population aging and also influence the social experiences of aging. Some key demographic trends include the rapidly increasing number of the “oldest old,” a more racially and ethnically diverse older population, more immigrants and foreign-born citizens among the elderly, changing causes of death, and greater human capital (education and work experience) and labor force participation among older adults. The overall implication of these trends is a large and growing number of relatively healthy, active older adults. The fact that population aging is a global phenomenon will probably also modify norms and expectations surrounding the aging process (see Hardy and Skirbekk, Chapter 7; National Research Council, 2012a).

Institutions and Policies

The next level is occupied by an array of social institutions and policies. A multiplicity of formal and informal social institutions structures the choices and decisions that individuals make as they move through later adulthood. For example, age-graded policy institutions such as Social Security and Medicare interact with other social factors (e.g., race, gender, education, prior work, and family experience) to shape the patterns of stratification and inequality among older adults. Social support, social integration, and social isolation are also institutionalized, with social norms and expectations generating known roles for aging adults (see Moen, Chapter 9).

Contexts and Environment

The macrodemographic trends (the first level) and institutions (the second level) are widely shared by many older adults living in the United States in the early 21st century. The social and economic context for all older adults is formed by both demographics—for example, the proportion of 65- or 75-year-olds in the population—and social policies— for example, Social Security laws. The effects of demographic conditions or social policies on any particular individual may vary considerably. At the next level, contexts and environment, more divergence emerges based on individual sociological characteristics and other factors. From the household to the neighborhood, school and workplace, religious communities and civic organizations, contexts and environments are important influences on the development and functioning of individuals at the same time as they respond to characteristics and behaviors of individuals as they age (see Cagney et al., Chapter 8). For example, neighborhood contexts can exert cumulative impact across the life course (Wen and Gu, 2011) and across generations (Sharkey and Elwert, 2011).

Structural characteristics of neighborhoods (e.g., racial/ethnic diversity) and the nature of the built environment may also affect aging outcomes (Browning et al., 2006).

Dyads and Small Social Groups

A further level is comprised of pairs of individuals (dyads) and small social groups of which virtually all older adults are members. This level has a significant impact on many outcomes among the aged. For example, Lindau et al. (2003) propose that health is determined within the social and cultural context of the dyad, and influenced by inputs of biophysical, psychocognitive, and social capital (Lindau et al., 2003). The most common and important dyad is the married couple or cohabiting partnership, at least for older men. Women are much more likely than men to be unpartnered, both because female life expectancy exceeds that of men and because women tend to marry men several years older than themselves (Lindau et al., 2007). Thus, differences in access to partnership mean that the aging life course tends to follow divergent trajectories for women and men in ways that tend to disadvantage women, socially, emotionally, and economically. Of course, unpartnered older adults need not live alone and most are not socially isolated (Cornwell, Laumann, and Schumm, 2008, p. 2). The authors find that age is positively related to the frequency of socializing with neighbors as well as participation in religious activities and volunteering (p. 12). Social networks important to older adults may span distances, ages, and relationships. Social networks, often measured as the others or “alters”

with whom people engage, for example in discussions of important matters, may consist of nuclear family, friends, more distant relatives, co-workers. Network members may know each other, may live with the older adult, may have frequent communication but do not need to have any of these characteristics (Cornwell, Laumann, and Schumm, 2008). Social networks have been linked to diagnosis and treatment of hypertension (Cornwell and Waite, 2012), to the potential of the person to act as a bridge between network members (Cornwell, 2011), and to sexual dysfunction in older men (Cornwell and Laumann, 2011).

Individual

Much of sociology, social demography, and social epidemiology focuses on outcomes at the individual level, often individuals aggregated into groups of some kind, perhaps by age, gender, race/ethnicity, or education. Examples include age differences in social participation (Cornwell, Laumann, and Schumm, 2008), obesity or smoking behavior of individuals embedded in different social networks (Christakis and Fowler, 2007, 2008), mortality of married versus unmarried men (Rendall et al., 2011), racial differences in chronic conditions (Hayward et al., 2000), or grief following widowhood (Carr, 2004). These studies of individuals may in turn explicate the role of the life course (in the case of age differences), social structures (in the case of networks), social institutions (in the case of marriage), social isolation (in the case of widowhood), or social stratification (in the case of racial differences in chronic conditions). A key contribution of social epidemiology at this level is its focus on the factors and processes that determines heterogeneity in the response of individuals or groups, and when that heterogeneity in response socially patterned. A focus on individuals can reveal much about the social contexts and processes that affect them.

Biological and Physiological

Humans are first and foremost social animals whose bodies evolved while perceiving and responding to social stimuli in ways that promoted their survival and adaptation. Thus, human physiology is attuned to characteristics of the social environment and interactions with others, and social behavior is likewise underpinned by complex biological processes (see Gruenewald, Chapter 10; Shanahan, Chapter 12). Perhaps for this reason, social conditions, such as isolation, poverty, low social status, or lack of social support, are strongly and consistently associated with poor health, and social risk factors rival or exceed traditional biomedical factors, such as smoking and cholesterol levels, in their power to predict poor health

outcomes (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, and Layton, 2010; House, Landis, and Umberson, 1988; Sharkey and Elwert, 2011).

Attention has turned recently to the ways that the social world “gets under the skin” to affect health and illness as individuals age. This has motivated the addition of biological, physiological, and functional measures to large-scale social surveys like the Health and Retirement Study, the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study, and the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (see Chapter 4). Linking biological and social processes is complex, because each of the processes is itself complicated, and because some research suggests interactions among these levels, so that the association between social risk factors and illness differs across states, regions, or countries (see Gruenewald, Chapter 10; Weinstein, Glei, and Goldman, Chapter 11; Shanahan, Chapter 12; Schnittker, Chapter 13).

Linking Multiple Levels

The idea that individuals are embedded in multiple layers of social units and organizations is well established. One of the main messages of Frank Furstenberg’s study of families living in inner-city neighborhoods was that families operate in the context of the neighborhoods and communities in which they are located: what parents can do for their children is partly determined by the resources available in the surrounding environment (Furstenberg, 1999). More recently, Small’s study of mother-to-mother networks at child-care centers found that individuals’ social capital depends fundamentally on the organizations in which they are embedded, and through multiple mechanisms, such organizations can create or reproduce network advantages for their members (Small, 2009).

A large body of research and theory also points to the importance of the macro levels that may appear to be far removed from individuals’ daily concerns. The political economy, as a whole, and specific state policies regarding entitlements, pensions, health care, and disability programs play an important role in shaping the health, financial resources, retirement decisions, and even marriage choices of older adults (see Marshall and Bengtson, 2011; Mayer, 2009).

Social experiences, such as social isolation, seem to affect biological and physiological outcomes, including blood pressure, sleep, and gene expression (Cacioppo and Hawkley, 2009; Cole et al., 2011; Hawkley et al., 2010). This appreciation of the impact of the social on the physiological is but a further illustration of the importance of examining linkages among multiple levels. The relationship between the social and the physiological goes the other way as well. Biologically based disease and disability certainly have an effect on the higher levels.

Stages of the Life Course

The multiple levels of social organization in which individuals are embedded in the conceptual model (see Figure 2-1) are by no means static as those individuals proceed through life (Hobcraft, 2006, p. 173). The model and its levels accommodate another source of dynamism and fluidity in individuals’ lives: temporal progression of the person through the stages of the life course, “a sequence of socially defined events and roles that the individual enacts over time” (Giele and Elder, 1998, p. 22).

The life course perspective considers developmental processes, culturally and normatively constructed life stages and age roles, demographic factors, biographical accounts, aging, the role of policies and institutions, and/or the association between events and understandings from birth to death (Mayer, 2009). It has helped researchers to model the social patterning of lives and consider the experience of aging as a result of institutions, policies, biological processes, and biography, all historically situated and interconnected with others (Hendricks, 2012; Mayer, 2009). The life course framework also attends to “the process of human growth and senescence within historical context, producing unique life experiences and trajectories for different birth cohorts” (Silverstein and Giarrusso, 2011, p. 35).

In the study of human development, adult development and aging, the life course paradigm has been extremely influential (Billari, 2009; Elder, 2002; Mayer, 2009). Since the 1970s, the extraordinary growth of national longitudinal studies of both adults and children—such as the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, the National Longitudinal Surveys, the Health and Retirement Study, and the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (see Chapter 3)—has enabled researchers to directly examine individual outcomes at multiple observation points, to situate lives within historical periods, and to trace trajectories of individual lives.

As empirical evidence demonstrating the impact of childhood social experiences and biological exposures on adult outcomes accumulates, scholars have begun to more explicitly connect very early with very late stages in the life course. Smith (2009), for example, assesses the effect of health in childhood on labor market outcomes many years later. He has found that poor childhood health has a quantitatively large effect on family income, household wealth, individual earnings, and labor support, even after family-specific effects are taken into account (Smith, 2007, 2009). In a related paper, Smith and Smith (2010) found that psychological problems and substance abuse during childhood have large effects in adulthood on the ability of those affected to work and earn, the likelihood that they are married, the size of family assets, and education completed (Smith and Smith, 2010). These effects are not due to co-occurring physical health problems; estimates controlling for within-sibling differences show that characteristics

of families common to siblings do not account for these differences. The “arm” of childhood (Hayward and Gorman, 2004) is indeed very long (see also Johnson and Schoeni, 2007; Luo and Waite, 2005; Warren, Sheridan, and Hauser, 2002).

The social structure of the life course as a system of age-graded social statuses has consequences for activities, expectations, behaviors, social roles, and physical and mental health (Clark et al., 2011). As the life course itself changes (see Angel and Settersten, Chapter 6; Hardy and Skirbekk, Chapter 7), the life stages are becoming less clearly defined, more porous, fluid, and diverse. It should also be mentioned that the specific ages that define each life course phase lack precision. The ages demarcating entry to a particular life course stage may vary by social class and cohort. For example, the age demarcations for middle age is usually defined as age 45, but depending on social class and educational attainment, age 45 can be the age at which one has a first birth, or when one enters the “empty nest” stage.

The model in Figure 2-1 shows stages of the life course from older adulthood back through gestation and early childhood. These stages are discussed below.

Older Adults

Older adults are clearly the most relevant target population of research for those who study aging. As adults move toward older age, activities and social roles tend to change. Many adults leave employment, or they leave a primary job for a second career or a different job (Gruber and Wise, 2005). They often experience declines in health, the loss of social network contacts (Cornwell, Laumann, and Schumm, 2008), and marital loss through widowhood. Both the risk of these changes and the adjustment to such losses are heterogeneous (Bonanno et al., 2002). Individuals’ subjective perceptions and objective situations also differ during these transitions (see Settersten and Mayer, 1997, on subjective age identification). The chronological age at which an individual becomes entitled to certain age-graded benefits or services has also varied over time and across countries or policy regimes, with substantial effects on behavior (Gruber and Wise, 2005). Likewise, cognitive skills change and with those changes come associated effects on wealth, wealth growth, and wealth composition in the individual’s retirement years (McArdle, Smith, and Willis, 2009).

Middle-Aged Adults

When individuals reach middle age, their health begins to change significantly and individuals diverge. Many individuals maintain physical, cognitive, and emotional health; others develop chronic disease, functional

limitations, and disability. This divergence is socially patterned, with more socially disadvantaged groups showing health declines much earlier than the more advantaged, including the onset of some age-related chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension) and disabilities. The number of biological risk factors that individuals have also diverges by race/ethnicity and education in the middle years (Crimmins and Beltrán-Sánchez, 2011; Crimmins and Seeman, 2004). For example, among people aged 51-61, the estimated prevalence of hypertension (a common risk factor for a variety of diseases) was 61 percent for black women compared to 34 percent for white women. The greater divergence in health by groups appears to be due to “a long-term and cumulative process of health disadvantage over the life cycle” (Hayward et al., 2000, p. 926).

Health in middle and older ages depends in part on social experiences during earlier stages. Hughes and Waite (2009) found that both physical and psychological health are affected by earlier marital loss, so that although those currently married enjoy better health, those who have ever been divorced or widowed are worse off than those who have never had a marital loss (Dupre and Meadows, 2007; Hughes and Waite, 2009). Zhang and Hayward (2006) found that women who have been divorced face increased risks of developing cardiovascular disease, perhaps due to the stresses accompanying marital breakdown.

Some research suggests that middle-aged adults might be particularly vulnerable to sudden system changes, such as those that occur during major wars or the transition of former socialist countries (Mayer, 2009). The same may be true for other unexpected losses such as unemployment during an economic downturn.

Young Adults and Youth

Recent advances in longitudinal data on the transition to adulthood, in particular the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (ADD Health) have led to an explosion of research on this stage in the life course. This longitudinal study of a nationally representative sample of adolescents in grades 7-12 in the United States during the 1994-1995 school year has produced a dataset that is innovative for its linkages among socioeconomic, family, individual, behavioral, biological and genetic levels (Harris and Cavanagh, 2008). The transition from youth to young adulthood is one of the most demographically dense in the life course, with frequent changes in living arrangements, educational enrollment, types and hours of employment, romantic and marital unions, and entry into childbearing (Rindfuss, 1991; Shanahan and Hofer, 2011). Experiences, exposures, and levels of educational attainment in the youth and young adult years may be pivotal for later stages of the life course (Crimmins and Cambois, 2003).

Gestation and Early Childhood

A large body of research points to the intrauterine environment and early childhood as critical developmental periods for later health and cognitive function (Cunha et al., 2006; Fogel and Costa, 1997; Johnson and Schoeni, 2007). Poor health at birth and limited parental resources (including low income, lack of health insurance, and unwanted pregnancy) interfere with cognitive development and health capital in childhood, reduce educational attainment, and lead to worse labor market and health outcomes in adulthood (Johnson and Schoeni, 2007). These effects are substantial, and they are robust to the inclusion of sibling fixed effects and an extensive set of controls. The results reveal that low birth weight (defined as under 5.5 pounds) ages people in their 30s and 40s by 12 years, increases the probability of dropping out of high school by one-third, lowers labor force participation by 5 percentage points, and reduces labor market earnings by roughly 15 percent (Johnson and Schoeni, 2007, p. 26). Little is known about whether these effects continue at the later stages—suggesting the need for aging research that reaches back to early childhood.

Outcomes in the Conceptual Model

Outcomes constitute the third dimension in the conceptual model. Figure 2-1 lists five outcomes of interests across the top of the cube: health, cognition, disability, social isolation, and socioeconomic status (SES). These serve as a possible set of outcomes to be considered, but they could be replaced by others, such as morbidity, longevity, mortality, social participation, social support, obesity, diabetes, retirement, emotional well-being, quality of life, caregiving, or labor force participation. The model, as presented, deliberately offers as examples outcomes that are general, important, and well researched, and that span disciplinary boundaries. The selection of outcomes to be studied in turn affects what theories of causation and translational mechanisms will be most useful in relating different levels of contexts and processes across the life course.

Health

The World Health Organization defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (World Health Organization, 2012). Health and long life are universally desired and are central to the daily experiences of all people. They become increasingly important at older ages as chronic conditions emerge, functional limitations appear, psychological health declines, and disabilities develop. Poor health and short life are key dimensions of social

disadvantage, especially by race (Crimmins and Seeman, 2004; Hayward et al., 2000; National Research Council, 2004). Social demography and social epidemiology have long-standing interests in health, including morbidity and mortality, and on health disparities.

Cognition

Significant changes in cognitive function develop with age. These changes are evident in several major aspects of mental ability, although age-related declines do not develop uniformly either within or across cognitive domains. The nature of the change that occurs, the point at which changes become apparent, and the magnitude and rate of change vary, depending on the cognitive function in question. The five major areas of cognitive ability, ranked by their sensitivity to variation at the high end of the cognitive spectrum, are learning and memory, executive function abilities (e.g., concept formation and abstract thought), language, visuospatial abilities, and sustained attention (the ability to focus and perform a simple task). Cognitive impairment has been shown to markedly reduce the survival prospects of individuals and is also associated with a marked deficiency in an individual’s quality of life and that of their caregivers (Matthews et al., 2009).

These processes are now being studied in the Healthy Brain Project at the National Institutes of Health, which focuses on the determinants of cognitive and emotional health. The multifaceted project will “assess the state of longitudinal and epidemiological research on demographic, social and biologic determinants of cognitive and emotional health in aging adults and the pathways by which cognitive and emotional health may reciprocally influence each other” (National Institutes of Health, 2012).

Disability

The risk of disability, defined broadly as “impairments in body functioning, limitations in activities, and restrictions in participation” (Freedman, 2011, p. 57), is age graded and unevenly distributed among groups. Freedman notes that “the consequences associated with loss of functioning can be far-reaching for individuals, families, and communities in terms of both economic costs and quality of life. As such, although not inevitable outcomes of aging, disability and functioning are central topics in the study of late life” (Freedman, 2011, p. 57). Although disability-free life expectancy has been increasing, the dynamic process behind such increase is yet to be fully explored (Crimmins et al., 2009).

Frailty is a clinical syndrome that muscle weakness, bone fragility, very low body mass index, susceptibility to falling, vulnerability to trauma,

vulnerability to infection, high risk for delirium, blood pressure instability, and severely diminished physical capabilities. Frailty connotes vulnerability to adverse outcomes and limited ability to respond to and recover from stressors. Frail older adults are at increased risk of mortality. Frailty and disability are associated but not synonymous. Behavioral and social risk factors are important in the development of frailty (Fried et al., 2004; Walston et al., 2006).

Social Isolation

Social isolation, a state studied by sociologists, is a surprisingly unhealthy state. In fact, the health risks associated with social isolation have been compared in magnitude to the well-known dangers of smoking cigarettes and obesity (House, 2001). There are a number of indicators of social isolation, including living alone, having a small social network, infrequent participation in social activities, that may be associated with health risks (Cornwell and Waite, 2009).

Much the same effects are experienced when there is perceived isolation, associated with feelings of loneliness and perceived lack of social support that are usually studied by psychologists. Indeed, loneliness is seen as a prevalent and serious social and public health problem (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010).

Research on loneliness, conducted mostly in Western countries, has shown that at any given time, 20 to 40 percent of older adults report feeling lonely (De Jong and Van Tilburg, 1999; Savikko et al., 2005; Theeke, 2009; Walker, 1993) and from 5 to 7 percent report feeling intense or persistent loneliness (Steffick, 2000; Victor et al., 2005). However, while socially isolated individuals tend to feel lonely, loneliness is not synonymous with objective isolation. Loneliness can be thought of as perceived isolation and is more accurately defined as the distressing feeling that accompanies discrepancies between one’s desired and actual social relationships (Pinquart and Sorensen, 2003).

Prospective studies have shown that feelings of loneliness predict depressive symptoms (Cacioppo, Hawkley, and Thisted, 2010), impaired sleep and daytime dysfunction (Hawkley, Thisted, and Cacioppo, 2009; Hawkley et al., 2010), reductions in physical activity (Hawkley, Thisted, and Cacioppo, 2009), and impaired mental health and cognition (Wilson et al., 2007). At the biological level, loneliness is associated with increased vascular resistance (Cacioppo et al., 2002; Hawkley et al., 2003); increased systolic blood pressure (Hawkley et al., 2010); increased hypothalamic pituitary adrenocortical activity (Adam et al., 2006; Steptoe et al., 2004), under-expression of genes bearing anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid response elements (GREs); over-expression of genes bearing response elements for pro-inflammatory

NF-κB/Rel transcription factors (Cole et al., 2007, 2011); and altered immunity (Kiecolt Glaser, Garner, and Speicher, 1984; Pressman et al., 2005). Moreover, an increasing body of research shows that feelings of isolation and loneliness predict mortality (Luo et al., 2012; Patterson and Veenstra, 2010; Shiovitz and Ayalon, 2010; Tilvis et al., 2011).

SES

SES can be measured in multiple ways (e.g., education, income, occupation, wealth, material deprivation, subjective social status, income inequality) and is one of the most robust predictors of health and well-being. It is also itself a measure of achievement, and its causes and consequences constitute one of the central topics of theory and research in sociology. SES is a frequently used predictor in social demography and social epidemiology (see Gruenewald, Chapter 10; Shanahan, Chapter 12), as those of high SES have an array of resources with which to pursue all goals, including health. These resources consist, of course, of financial resources, but also, in part, of information, social contacts, generally salubrious local environments free of toxins, access to health care, and skills in evaluating and adopting new treatments and technologies. Those with low status are more often exposed to stress, have few resources to counter stress, lack access to health care or face care of poor quality, tend to have poorer health habits, and face exposure to environmental toxins (Miech et al., 2011). One key dimension of SES—education—leads to desirable outcomes because it provides training in the acquisition, evaluation, and use of information, and because it helps develop self-direction and self-efficacy (Mirowsky and Ross, 2003; Ross and Mirowsky, 2001). SES has been consistently linked to health outcomes across the life course, regardless of how it is measured and regardless of the measure of health used (Bruce et al., 2010; Phelan et al., 2004; Smith, 2007).

Theorizing the Conceptual Model

The three-dimensional conceptual model enables the consideration of, but does not articulate, relationships, causal mechanisms, interacting effects, or translation mechanisms that connect the different levels, stages, and outcomes. Theory can help specify causal pathways, within and among the cells in the model (Diez Roux, 2003). Each cell of the conceptual model includes many opportunities for further theorization.

Ross and Mirowsky (2001), for example, employed a series of multilevel models to test whether structural characteristics of the neighborhood indirectly influence health through individual-level processes such as physical activity. They found that neighborhood disadvantage contributes to

increases in perceived disorder within the neighborhood, which discourages walking and is consequently harmful to health. They further found that the effect of perceived disorder was partially mediated by fear. People who fear being robbed or attacked in their neighborhood were unlikely to walk for recreation or transportation (Ross and Mirowsky, 2001).

Theory may also help identify common biological mechanisms (e.g., cortico-striatal and limbic systems) behind a wide range of socially graded experiences and contexts that produce pro-inflammatory patterns (see Shanahan, Chapter 12). This very different set of questions can also be located within the three-dimensional model.

Cagney et al. (see Chapter 8) call for greater efforts to theorize the impact of multiple social contexts on older adults. They draw attention to the simultaneous and interactive effects of geographic, institutional, and social network influences on the individual and collective experience of aging.

Chronological age and time and historical epoch are other influences that permeate the entire cube. These are period and cohort effects, in addition to individual age and life course. “Period refers to a specific time point, such as a year or decade, and period effects are changes among people of all ages from one period to another period. Birth cohort refers to a group of people who are born at about the same time, and cohort effects are changes across these groups, regardless of age” (Schwadel, 2010, p. 3) The outcome of social isolation, for example, can be examined not only over an individual life course but also from vantage points of period and cohort. Cross-cutting themes, such as inequality and heterogeneity, could also be explored across all the different cells of the conceptual model, to theorize their impact on the experience of aging.

Older adults in the early 21st century may be able to take advantage of information technology to stay connected with relatives living far away, lessening isolation (period effect). The 20th century cohorts that experienced a high rate of divorce may become more isolated in old age due to family fragmentation (cohort effect). In addition to these inter-cohort effects, it is increasingly important to consider the effects of intra-cohort changes with age (Yang and Lee, 2009).

The conceptual model elaborated here both situates the many different ways the study of aging has been approached and suggests many different opportunities that remain for further study.

Recommendation 1. The National Institute on Aging should engage researchers in the development of a conceptual model, or a number of conceptual models, for social processes in aging over the life course in multiple dimensions.

Greater theorization is needed to explicate the interrelationships among the different levels, stages, outcomes, and cells of the conceptual model. Further data and transdisciplinary work, as discussed in the next chapters, are imperative and the research community is urged to think carefully and conceptually about the linkages across levels, stages, outcomes, and cells. Indeed, the model offers a heuristic for this but points to no specific cells as more important than others; what is important is the consideration of context and levels. It should be noted, as Angel and Settersten observe “aging is one of the most intricate scientific puzzles, posing many significant challenges for individuals, families, and societies” (see Angel and Settersten, Chapter 6).

Recommendation 2. The conceptual model, or models, should be used by the National Institute on Aging to serve as the basis for developing a standard set of key measures, across disciplines, for use in surveys and other types of data collections and analyses that focus on aging issues.

The process for obtaining those measures from databases is discussed in Chapter 3.