3

Leveraging Health Care Coalitions

Highlights of Points Made by Individual Speakers

- Pediatric surge capacity remains a challenge.

- Barriers to building capability include lack of understanding among stakeholders of each other’s needs and capabilities, lack of local knowledge about available guidance and tools, and cost.

- A coalition’s role is translating across silos, promoting day-to-day pediatric readiness, helping communities navigate through numerous disaster preparedness tools, and partnering to make the best use of available resources.

- National neonatal and pediatric disaster drills are needed.

This chapter focuses on how best to leverage existing coalitions and collaborations for the benefit of children. Panelists provided federal, state, and local perspectives on coalition challenges and best practices, and discussed duality of services and improving everyday capacity. Securing buy-in from important stakeholders and coordinating work across regions and sectors are a few of the challenges discussed, as well as highlighting the need for central coordination and broadening of stakeholders in coalitions past simply including pediatric providers.

Giving an example of ways to augment pediatric surge capacity, Andrew Rucks of the University of Alabama at Birmingham noted that he also serves as director of the Southeastern Regional Pediatric Disaster Surge Network, which currently includes Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee, and will soon include Kentucky, North Carolina, and South Carolina. The network is an emerging multi-

state coalition of health departments, children’s specialty hospitals, regional hospitals, emergency responders, first responders, and local community pediatricians who are coming together to provide surge capacity in a region of the country that has very limited surge capacity to deal with children. The network has developed a mission and is working to operationalize and exercise the surge network, pointing to an earlier referenced challenge about the lack of pediatric focused exercises and drills. There are numerous challenges to managing this multistate coalition consisting of a wide variety of players, Rucks said. And while regions are becoming better prepared to deal with large-scale events (e.g., hurricanes), Rucks suggested that they are not as well prepared to deal with the smaller-scale issues that overwhelm the needs of one or more local pediatric specialty hospitals.

FEDERAL PERSPECTIVE: THE HOSPITAL PREPAREDNESS PROGRAM

Richard Hunt, senior medical advisor for the National Health Care Preparedness Programs at the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), provided federal-level perspective on health care coalitions. Currently, the U.S. health care delivery system is focused on cost reduction. This includes service retraction, which results in just-in-time operating principles and staffing. Although U.S. health systems emergency preparedness and response mechanisms are established and operational, they are fragmented and are restrained by a just-in-time approach, Hunt said. The country continues to experience overcrowding in emergency departments with limited mechanisms to reallocate patients throughout the hospital or the community. Although the concept of surge capacity has been discussed for well over a decade, a March 2013 Government Accountability Office report still highlights surge capacity as a challenge. Work has been done on allocation of scarce resources and introducing the concept of crisis standards of care, where population outcomes would be optimized over individual patient outcomes (Devereaux et al., 2008; IOM, 2012). Although this difficult conversation is further complicated when children are introduced to the discussion, it is an important piece in planning if a scenario occurred where real limitations were placed on resources or capabilities.

Hunt described some of the financial realities of disaster preparedness and response. National health care expenditures grew 4

percent to $2.5 trillion in 2009, or $8,086 per person, and accounted for 17.6 percent of gross domestic product. Hospital expenditures for 2010 were $814 billion according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Assuming there were 5,754 hospitals in the United States (per the American Hospital Association), the average hospital expenditure was approximately $141 million that year. In contrast, the total Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) budget for 2012 was $347 million, which Hunt pointed out is 0.0001 percent of overall national health expenditures.

With that in mind, Hunt said, the current need is a comprehensive national preparedness and response health care system that is scalable and coordinated to meet local, state, and national needs, and is financially sustainable. This requires a multifaceted effort, including integrating with and improving the efficiency of daily health care delivery, and applying a population-based health care–delivery model for disaster response. Toward that end, having defined health care preparedness capabilities (i.e., goals) and performance measures is very important.

Fifteen capabilities for national health care preparedness are outlined by ASPR in the National Guidance for Health care System Preparedness (ASPR, 2012). Health care system preparedness is one area where HPP is currently focusing efforts. Hunt described health care coalition development as the foundation for health care preparedness capabilities. The concept is one of inclusiveness, like a web, where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Per the ASPR guidance, the list of health care coalition essential partner memberships includes “specialty service providers (e.g., dialysis, pediatrics, women’s health, stand-alone surgery, urgent care).” It will be important moving forward for pediatrics to interface with coalitions, and for pediatric coalitions to interface with the health care preparedness program. Hunt noted that the Pediatric Preparedness Resource Kit1 released by the American Academy of Pediatrics includes an entire section on pediatric coalitions.

Hunt described four key considerations for developing a preparedness and response coalition. First, the coalition must be functional (i.e., not simply a mechanism for further discussions). Second, it is important to consider the percent of the population covered in a particular area relative to resources (e.g., how a very rural coalition

___________________

1Available at http://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Children-and-Disasters/Documents/PedPreparednessKit.pdf (accessed September 9, 2013).

compares to one that covers a much larger percentage of the population). The third consideration is the necessary linkage of preparedness with daily delivery of health care. Finally, risk needs to be taken into account. One aspect of risk could be, for example, how many coalitions cover a particular earthquake fault line? But another risk consideration is vulnerable or at-risk populations (e.g., older adults and children). Hunt stressed that ASPR is committed to building functional coalitions for national health care preparedness that not only work, but that will serve children as well.

LOCAL PERSPECTIVE: THE CALIFORNIA NEONATAL/PEDIATRIC DISASTER COALITION

Patricia Frost, director of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) for Contra Costa County Health Services in California, described a local, grassroots coalition-building effort and how coalitions can help overcome barriers to pediatric disaster preparedness. Contra Costa County in California has a population of 1.1 million, with about 250,000 children. A 2008 EMS for Children Program Assessment revealed that the county has lost more than 40 percent of its total pediatric bed capacity in the prior 5 years, and had approximately 1 licensed pediatric bed for every 16,000 children in Contra Costa. No one knew or considered the impact of this to the health system, she said.

“In most communities across the nation, less than four to five critical pediatric patients, per hospital, arriving on the same day would completely saturate the pediatric health care system in that community.”

—Patricia Frost

A primary barrier to building capability, according to Frost, is the lack of understanding among stakeholders of each other’s needs and capabilities. Frost observed that many times what one group perceives as simply excuses from another are, in fact, real barriers for them. A major role for a coalition is to translate across the gaps and silos, and to help find workarounds for complex problems.

Frost described the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic as a “pediatric disaster near miss” that helped launch the California Neonatal/Pediatric Disaster Coalition.2 The first challenge for the grassroots effort to

___________________

2Frost referred participants to the coalition’s GoogleSite, https://sites.google.com/site/pedineonetwork and the Contra Costa Pediatric Disaster Preparedness Resources website,

enhance pediatric capacity was to get people’s attention. The coalition addressed this by telling a compelling story about the lack of licensed pediatric beds in the state. The state had never done a bed capacity analysis for neonatal and pediatrics, citing lack of funding. Frost found that California and the West Coast’s pediatric “safety net” consists of about eight key regional centers that handle more than 55 percent of pediatric inpatient care. Every one of these is on a fault line at high risk for earthquakes. If, for example, Southern California lost its infrastructure for neonatal intensive care, providers may have to look as far as Texas to find bed capacity.

Another role of the coalition is to promote a strategic plan to improve day-to-day pediatric readiness. We need to plan for those situations that fall in between daily triage, when resources are available relative to patient demand and normal standards of care are applied, and full-scale disaster, when patient needs outstrip resources and crisis standards of care come into play. It does not take much to overwhelm the current system of pediatric care, Frost said. According to her experience, in most communities across the nation, less than four to five critical pediatric patients, per hospital, arriving on the same day would completely saturate the pediatric health care system in that community.

Lack of local knowledge about available guidance and tools is another barrier to preparedness. The coalition’s role is the navigator through numerous (often overlapping) disaster preparedness tools, helping communities understand what they need to prepare for and how. With regard to tools, Frost also advocated for the use of communication technology under normal conditions. The goal is to embed technology, telemedicine, and consultation into normal pediatric care because it builds relationships and competencies. This knowledge, shared now, pays dividends when the power is lost later.

Cost is an ongoing barrier to preparedness. The coalition’s role is not to raise money for itself, but rather to partner with organizations that have resources, and to direct communities to the training and other resources already available for free.3 In addition, although hospitals are often competitors in a business sense, they must “share without regard to turf” when it comes to readiness.

_________________________________________________________

http://cchealth.org/ems/emsc-disaster-prepare.php, for further information (accessed September 9, 2013).

3Frost cited, for example, the University of New Mexico Pediatric Emergency Online Education Program, available at http://hsc.unm.edu/emermed/PED/educationonlineEd.shtml (accessed September 9, 2013).

Competency requires volume, and everyone can make a contribution, Frost said. The role of the coalition is to help set reasonable expectations, and craft messages to reduce fear. “Special” may be interpreted as “too scary to handle” for a community hospital, and adult providers may lack confidence in dealing with pediatric patients. Coalitions, both formal and informal, mobilize partners, and small collective actions matter. The California Neonatal/Pediatric Disaster Coalition has grown from a handful of key people to more than 150 champions statewide.

Frost concluded noting that we are very good at multi-agency and organization mobilization to save one or several children (for example, the rescue of 18-month-old Jessica McClure when she fell 22 feet down an 8-inch-wide well in 1987), but we tend to lose our focus when many more children are involved. Frost suggested that the next priority for the HPP should be a national neonatal and pediatric disaster drill. This, she said, could be the single most important vehicle to improve capability.

HOSPITAL PERSPECTIVE: NEW YORK CITY PEDIATRIC DISASTER COALITION

On the evening of Saturday, May 1, 2010, a sports utility vehicle packed with explosives was parked near Times Square in New York City, across the street from the theater where the family musical The Lion King was playing. The bomb failed, but had it exploded, there would likely have been numerous children in the area. George Foltin, vice chair of clinical services at Maimonides Infant and Children’s Hospital, described a study conducted by the New York City Pediatric Disaster Coalition to determine how many pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) beds were available in New York City on that day at that time. Although New York has a very sustainable and robust health care system and many pediatric intensive care beds, on that night only 21 percent of the pediatric beds were available, or 32 total beds. This potential disaster, paired with the bed census study, demonstrates the need to develop pediatric critical care surge capacity to increase the number of available beds in an emergency.

Coalition-Developed Resources

During the past decade, there has been a strong coalition between the New York City Department of Health and the health care sector. Because there are now hospitals focused exclusively on children, general hospitals have probably done the least thus far to prepare for children. Foltin cited as an example the 2008 development of guidelines to help hospitals prepare to receive children in a disaster. The resource guides general hospitals on elements such as security, how to put a baby in an adult bed, what kind of food and how much should be provided for children, and so forth. A pediatric disaster tabletop exercise was also developed to help hospitals exercise their plans.4 Another resource the New York coalition developed for out-of-hospital pediatric disaster preparedness describes the elements of disaster planning and management for pre-hospital providers.5

“Major pediatric centers must be able to surge as critically ill children are best served at specialty centers.”

—George Foltin

The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene also directed federal funds for a formalized Pediatric Disaster Coalition of hospitals, public health entities, municipal services, and community groups. The coalition is focused on effectively matching critical assets and resources to victim’s needs during and after a large-scale disaster affecting children, neonates, and women in labor. The coalition will also develop and expand ongoing pediatric disaster preparedness efforts through advisory and coalition-building activities.

Continuing to describe resources his coalition has developed, Foltin explained that a child’s chances of survival are heavily dependent on the early chain of events, including triage, tiering, and transport (e.g., whether the child gets access to pediatric expertise right away, or whether they receive interim treatment at a facility not set up to handle children, followed by transport elsewhere). To help address this, the Pediatric Disaster Coalition created new guidelines for first responders, recommending transport of pediatric patients to pediatric receiving hospitals. A memorandum of understanding was established with the fire

___________________

4The hospital guidelines and the tabletop exercise toolkit are available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/em/emergency-ped.shtml (accessed September 9, 2013).

5Available at http://cpem.med.nyu.edu/teaching-materials/pediatric-disaster-preparedness (accessed September 9, 2013).

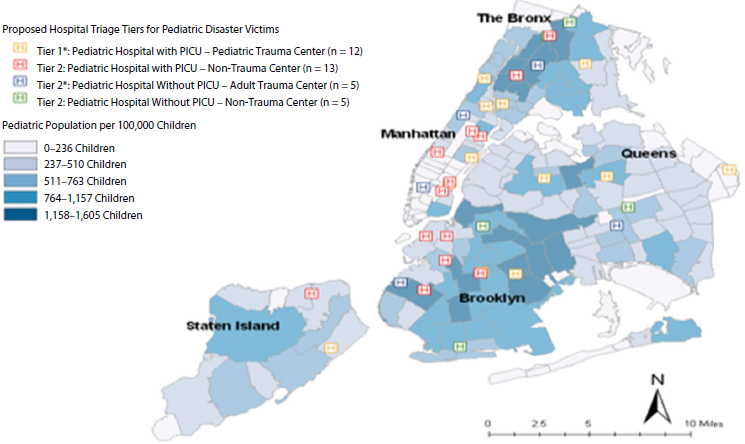

department and EMS for inter-hospital transport after a disaster, because children may not have been initially transported to pediatric receiving hospitals. Pediatric intensive care surge plans were also developed, increasing pediatric surge bed capacity by an additional 128 beds above the baseline of 238. The coalition also worked with EMS to modify their triage process for children, and developed proposed hospital triage tiers for pediatric disaster victim transport based on pediatric capability of hospitals relative to the pediatric population (see Figure 3-1).

Foltin mentioned the Pediatric Fundamental Critical Care Support curriculum developed by the Society for Critical Care Medicine as one resource for hospitals to train providers in pediatric care during a disaster.6 Other coalition activities Foltin mentioned include pediatric tabletop and full-scale exercises of PICU Surge Plans, activities focused on neonatal and maternal health, and a working group to study the successes and gaps in the pediatric response to Hurricane Sandy.

FIGURE 3-1 Proposed hospital triage tiers for pediatric disaster victims mapped against pediatric population density.

NOTE: PICU = pediatric intensive care unit.

SOURCE: Foltin presentation, June 10, 2013, citing Dana Meranus, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, April 2009.

___________________

6Avai Septemb ilable at www.sccm.org/Fundamentals/PFFCCS/Pages/default.aspx (accesssed September 9, 2013).

In conclusion, there must be a plan and communication, Foltin said. Major pediatric centers must be able to surge as critically ill children are best served at specialty centers. Primary transport should be to these centers, and inter-hospital transportation must be in place for children initially transported elsewhere. If this is not possible, general hospitals that are used to serving adults should have plans in place to properly take care of children. Building on just planning, resources, and drills are essential, he noted. Providers who do not routinely care for children often do not understand the subtleties, and many are very intimidated by it. If we do not prepare providers for the challenges and horrors of taking care of large numbers of badly injured children, they will not be able to care for the children successfully (or for adults, or even for themselves).