Highlights of Points Made by Individual Speakers

- Many deficiencies exist in the data for preparedness planning related to children.

- The basic goal with respect to disasters is to make children, families, and communities more resilient and less vulnerable.

- Adults and children may initially persevere following a traumatic event, but the resilience can erode the longer recovery takes, and the more stressful the recovery process is over time.

- Progress continues to be made in the implementation of recommendations in 11 categories from the 2010 report authored by the National Commission on Children and Disasters.

This report begins with an overview of the specific impact of disasters on children by Irwin Redlener, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University. He explained the important differences between lessons learned and lessons acted on, and realistic goals to keep in mind regarding children in these precarious situations. This is followed by a review of the recommendations from the 2010 National Commission on Children in Disasters (NCCD) report and updates on progress being made in different sectors around the country.

NEEDED FOCUS ON CHILDREN AND FAMILIES

There are tremendous deficiencies in the data needed to plan appropriately for children, said keynote speaker Redlener, and as a

population they do not have their own voice to use to their advantage. Children have very long memories, he continued, and the impact of the trauma associated with both the disaster itself, and prolonged or difficult recoveries, can last a very long time.

Lessons Learned Versus Actions Taken

People often look back at their experiences and call them “lessons learned.” But Redlener highlighted the need to differentiate between something that happened, and something that happened that led to preventive actions to mitigate future adverse events. He offered several examples from the events that occurred between October 24, 2012, and May 31, 2013. During this 7-month period, there were 9 major incidents: Hurricane Sandy on the East Coast; the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Newtown, Connecticut; bombings at the Boston Marathon; an explosion in a fertilizer plant in West, Texas; letters containing Ricin mailed to officials in Washington, DC; massive flooding in the Midwest; two EF5 tornadoes within 2 weeks in Moore and El Reno, Oklahoma; and a bridge collapse in Mount Vernon, Washington. Four of these incidents happened in 1 week, between Monday and Friday of April 15 through April 19 (Boston bombings, West explosion, DC Ricin letters, and Midwest flooding).

Children’s Near Misses

Data are difficult to obtain, but it is estimated that across these 9 events there were 176 fatalities, 46 of which were children or adolescents (26 percent). Redlener also described some of the “close calls” in these events, situations that could have easily been far worse with respect to child injuries and fatalities. For example, during Hurricane Sandy, the New York University Langone Medical Center evacuated neonates from its neonatal intensive care unit. Photographs of people carrying tiny newborn babies down a dark hospital stairwell were front-page news. While evacuation helped to ensure continued intensive care, Redlener suggested that, had we learned from Hurricane Katrina and taken action to protect generators, fuel supplies, electrical systems, etc., there may not have been a need to move these delicate patients. In Boston, there happened to be very few children at the marathon finish line when the bombs detonated. What if, Redlener said, there had been a third-grade

class watching the end of the marathon at that time? In West, Texas, the plant explosion caused extensive damage to the middle school and high school. Because the explosion happened after school hours, the middle school students were gone, and although the high school track team was returning to the school from an event, they decided to stop along the way for something to eat, delaying their return to school. Although hundreds of schools are in Oklahoma’s “Tornado Alley” (most without appropriate storm cellars or other safe havens), the Moore, Oklahoma, tornado only destroyed one school (killing seven people in the school). In Mount Vernon, Washington, there were no children in the vehicles that plunged into the water when the bridge collapsed. Thankfully, there was not a school bus on the bridge at that time, he noted.

Turning Learning to Action

The questions, Redlener said, are what are we actually learning from these events and near misses, and how fast are we filling the gaps in preparedness and response that are identified? During only 215 days the country faced a hurricane superstorm, a school shooting, terrorism, an industrial accident, severe flooding, tornadoes, and infrastructure failure. Disasters are not going away. More severe weather is inevitable. Pandemic viruses continue to emerge. The country faces potential cyber attacks, nuclear plant meltdowns, improvised nuclear devices, chemical spills, earthquakes, and the list goes on.

Are we learning from these tragedies and close calls? For example, it is clear that children must be protected in schools. Alabama now requires newly built public schools to have adequate protection from tornadoes, but Redlener said he was not aware of any similar action in the Oklahoma State Legislature thus far. There is limited understanding about how to protect backup generators in hospitals. There is also a lack of preemptive evacuation protocols. Shelters, even those designated for families, are often ill prepared for children, lacking diapers, cribs, and baby food.

Recovery

Once the initial disaster event is over, it can take a very long time for a community to return to a normal level of functionality. When a community is at high risk for further disaster events, Redlener said, the

goal is not to achieve the pre-event normal, but rather to achieve a new normal with better infrastructure and stability. Redlener referred to the recovery of infrastructure as “façade recovery.” The buildings are rebuilt, the infrastructure is repaired, and there is the appearance of recovery. The recovery of the impacted population, however, takes much longer. He noted that surveys done 3, 5, and 7 years after Hurricane Katrina still indicated ongoing effects of the trauma.

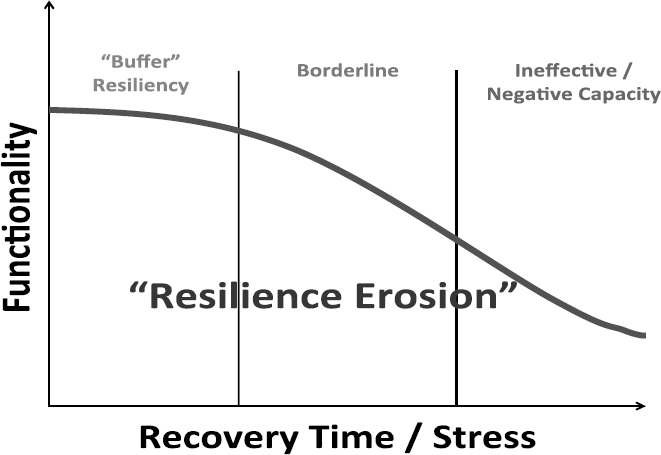

Redlener also described the concept of “resilience erosion” (see Figure 2-1). People, including children, can initially persevere through a traumatic event. Children are buffered from stress by resilient adults who protect them through the period of trauma and recovery, and transmit a sense of resilience. However, the longer recovery takes, and the more stressful the recovery process is, the more difficult it is for the adult to remain a resilient buffer for the children. After weeks, months, and even years of waiting for the situation to improve, parents who were once strong begin to lose their ability to provide an emotional and functional safety net for their children. Adding to the stress is the lack of any central function that coordinates the various recovery assets available from federal, state, and local agencies, nonprofit organizations, the Red Cross, insurance companies, banks, and others. Instead, individuals who have been affected by the disaster must navigate the highly complex bureaucratic process on their own.

Setting and Achieving Goals

The basic goal with respect to disasters is to make children, families, and communities less vulnerable, and more resilient and safe. Toward this end, the 2010 NCCD report recommends specific actions to be taken to improve preparedness, response, and recovery for children (NCCD, 2010; discussed further by Schonfeld and Dodgen in the next section). In setting and achieving goals, there is what Redlener called a “denominator problem.” If achievement is thought of as a fraction, what has been completed is the numerator and what is still needed is the denominator.

FIGURE 2-1 Resilience erosion.

SOURCE: Redlener presentation, June 10, 2013.

Government agencies are often interested in the numerator, and issue long lists of the progress that has been made. But the denominator of “continuing needs” is huge, he said, and because of this, children are still at risk. Through focusing more on the denominator—what is still left to be done—more needs can be identified.

There are definitely wins, Redlener stressed. There is leadership buy-in to the concept that children need to be protected, there is embedded pediatric expertise throughout government, and there are many advocates. But federalism and politics run counter to national disaster planning. Washington’s priorities are not necessarily the end user’s priorities, and it is the local governments who determine how and when they will spend money and what their priorities are. Further, the research base on children and disasters is insufficient, and preparedness and response funding continues to be cut. Redlener pointed out that in comparison to fiscal year (FY) 2010, the President’s submitted budget for FY 2014 shows funding for the Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) cut by 35 percent, state and local preparedness programs cut by 62 percent, and the elimination of the Academic and Public Health Preparedness Centers that had been promised a 5-year lifespan.

There are many community-based programs addressing preparedness. But Redlener suggested that the scale is too large to be handled solely on a local basis. High-functioning community-based models of children’s preparedness are necessary, but are not replacements for government initiatives and large-scale funding.

In conclusion, Redlener said that with regard to children we should be hoping for the best and preparing for the worst, but given the economy, the political deadlock, and children’s status among national priorities, we are instead hoping that we keep dodging the bullets.

2010 NATIONAL COMMISSION ON CHILDREN AND DISASTERS RECOMMENDATIONS

The NCCD 2010 Report to the President and Congress1 provided recommendations in 11 major categories (see Appendix H). David Schonfeld, director of the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement and former Commission member, shared his perspective on some of the progress made thus far in 8 of the 11 categories (omitting the last 3 due to time constraints).

Integration

The first NCCD recommendations on disaster management and recovery are really about integration, Schonfeld said. Recommendation 1.1 from the report is to “distinguish and comprehensively integrate the needs of children across all inter- and intra-governmental disaster management activities and operations.” The recommendation specifies further that children should not be grouped in an “at-risk” category, but should instead be pulled out for separate consideration. Schonfeld listed several examples of how the needs of children are now being considered

___________________

1The National Commission on Children and Disasters was authorized under the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2008, signed into law by President Bush on December 26, 2007 (P.L. 110-161). The Commission was charged with examining children’s needs relative to disaster preparedness, response, and recovery, and the status of existing laws, regulations, policies, and programs relevant to meeting such needs. The final Commission findings and recommendations were delivered to President Obama and Congress in October 2010. The Commission was terminated in April 2011, per its charter. See http://www.ahrq.gov/prep/nccdreport for further information (accessed September 8, 2013).

in planning, response, and recovery efforts, including the establishment of children’s working groups at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), as well as significant focus on the needs of the children by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Recommendation 1.1 also specifies that “the Executive Branch at all levels of government should establish and maintain permanent focal points of coordination for children in disasters that are supported by sufficient authority, funding and policy expertise.” Schonfeld said that significant progress has been made in incorporating pediatric subject-matter expertise and policy expertise. However, he noted that there are concerns about the permanence of these efforts and whether the experts actually do have sufficient authority to effect change on an ongoing basis. Of particular concern is the adequacy of funding. One opportunity to enhance integration comes under the Pandemic and All-Hazards Preparedness Act reauthorization, which calls for the establishment of a National Advisory Committee on Children in Disasters. According to Schonfeld, it is expected that this committee will have sufficient resources, support, and potential influence. But, as noted earlier by Anderson, there is uncertainty on where this committee will live, which reinforces the overall need for centralization for these issues and resources.

One gap in integration highlighted by the NCCD was the lack of inclusion of education, child care, juvenile justice, and child welfare systems into disaster planning, training, and exercises. Progress in this area has been hindered in large part by funding reductions. These partners are struggling to simply meet their core missions, and there is little to no supplemental funding to meet specific disaster preparedness response goals. If this is not remedied, Schonfeld said, much of the considerable progress that has been achieved stands to be lost.

Mental Health

Recommendation 2.1 in the report states that “HHS should lead efforts to integrate mental and behavioral health for children in public health, medical, and other relevant disaster management activities.” Although there has been progress in this area, Schonfeld said that funding limitations have compromised the federal agencies and the nonfederal partners’ ability to enhance pre-disaster preparedness in pediatric

disaster mental and behavioral health (e.g., psychological first aid, bereavement support, brief supportive interventions). Such preparedness training would be geared toward mental health professionals and other individuals who work with children (e.g., teachers). With regard to preparedness training, Schonfeld cautioned that “just-in-time” training is usually not in time. As an example, he described meeting with the school staff just after the shooting in Newtown, Connecticut. He observed that it was very difficult for the staff to process any information or training at that point.

Recommendation 2.4 calls for strengthening the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP) to better meet the mental health needs of children and families. Schonfeld said that follow-up conversations (after the NCCD disbanded) with representatives of the CCP indicated that FEMA was generally in agreement with the changes recommended by the Commission, and was seeking mechanisms to implement them. Although overall progress toward successful implementation is not yet clear, there are some examples. Schonfeld cited the Crisis Counseling Grant awarded to New Jersey in response to Hurricane Sandy, which includes a community liaison, numerous children’s specialists, and an intervention-based program to ensure that children’s disaster mental health needs are addressed effectively and efficiently. Similar efforts are also under way in Oklahoma.

Child Physical Health and Trauma

Recommendation 3.1 calls on Congress, HHS, and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)/FEMA to ensure the availability of and access to pediatric medical countermeasures. A recent Government Accountability Office report found that significant progress has been made in furthering the development of medical countermeasures (MCMs) for children; incorporating children’s needs into planning at the state and local levels; and developing and distributing dosing and administration guidance materials for parents and other caregivers (GAO, 2013). There has also been attention to increasing the relative proportion of MCMs in the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) that can be used for children. Pediatric experts now advise on the content of the SNS to ensure that pediatric needs are represented, and emergency use authorizations (EUAs) have been developed proactively so that stockpiling of MCMs used under EUAs is permitted. Despite this

progress, challenges remain in the development, testing, and purchasing of sufficient pediatric MCMs. Most worrisome, Schonfeld suggested, is the erosion of funding to support the SNS, which threatens the ability to maintain even the current level of readiness in the SNS for pediatric MCMs.

Recommendations 3.2 and 3.3 advise HHS and the Department of Defense to enhance pediatric capabilities of their disaster medical response teams and to ensure that health professionals who may treat children during disasters have adequate pediatric disaster clinical training. In this regard, the National Disaster Medical System (NDMS)2 has made significant efforts to increase the number of providers with pediatric expertise, but Schonfeld said that this effort by NDMS does not translate directly to comprehensive pediatric readiness in the field.

The NCCD also recommended establishing a formal regionalized pediatric system of care to support pediatric surge capacity during and after disasters. Schonfeld highlighted the NCCD’s concern that the country is not yet prepared to accommodate a surge in pediatric emergency medical trauma that may occur during a disaster, although, as of yet, no North American emergency to date has overwhelmed intensive care unit services on a widespread basis since the modern development of the field of critical care. However, planners are not optimistic that this will always be the case, and important progress on Pediatric Emergency Mass Critical Care has been made in recent years (Kissoon, 2011).

Another recommendation in this area calls for prioritizing the recovery of pediatric health and mental health care delivery systems in disaster affected areas. There has been no progress in establishing a funding mechanism to support the restoration and continuity of for-profit health and mental health services for children, and this remains a significant vulnerability, Schonfeld said.

___________________

2The NDMS is a federally coordinated system to provide disaster medical care to the nation. The mission of NDMS is to “temporarily supplement federal, tribal, state and local capabilities by funding, organizing, training, equipping, deploying and sustaining a specialized and focused range of public health and medical capabilities.” For further information, see http://www.phe.gov/preparedness/responders/ndms/Pages/default.aspx (accessed September 9, 2013).

Emergency Medical Services and Pediatric Transport

Recommendation 4.1 states that “the President and Congress should clearly designate and appropriately resource a lead federal agency for emergency medical services with primary responsibility for the coordination of grant programs, research, policy, and standards development and implementation.” Although Schonfeld opined that this remains a need not only for disaster preparedness, but also for optimizing routine pediatric emergency medical services across the country, this view may not be uniformly shared across the emergency medical services (EMS) community. Given that EMS interfaces with so many different federal agencies, creating one federal lead may not solve issues that reach across so many areas.

Schonfeld described the commission’s call for efforts to “improve the capability of emergency medical services to transport pediatric patients and provide comprehensive pre-hospital pediatric care during daily operations and disasters,” and to “develop a national strategy to improve federal pediatric emergency transport and patient care capabilities for disasters.” The limited federal and state capability to accommodate a major pediatric surge requiring transport of a large number of pediatric patients is a significant vulnerability.

Disaster Case Management

The single recommendation in this area, Section 5, states that “disaster case management programs should be appropriately resourced and should provide consistent holistic services that achieve tangible positive outcomes for children and families affected by disasters.” Further, “government agencies and NGOs [nongovernmental organizations] should develop voluntary consensus standards on the essential elements and methods of disaster case management including pre-credentialing of case managers and training that includes focused attention to the needs of children and families.” Case management of a family is much more than making sure they have a place to live temporarily, Schonfeld explained.

To this end, the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) is developing a model of case management that provides more comprehensive services and addresses the needs of children and families

more appropriately.3 Schonfeld noted, however, that these standards have not yet been broadly adopted.

Child Care and Early Education

In Section 6, the NCCD recommended that “Congress and HHS should improve disaster preparedness capabilities for child care,” including requiring states to include disaster planning, training, and exercising within the scope of minimum health and safety standards for child care licensure or registration, and requiring Head Start Centers to have disaster preparedness capabilities and to provide basic disaster mental health training for their staff.4

There is some growing interest in disaster preparedness among Head Start Programs. Schonfeld cited as an example a recent workshop sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics at the Head Start Leadership Institute in Washington, DC. In addition, ACF issued a proposed regulation that would require emergency preparedness and response planning for providers serving children who are receiving child care development fund assistance. Such planning would include provisions for evacuation and relocation, sheltering in place, and family reunification. Despite these efforts, most of the recommendations in this section have not yet been implemented, and the state of readiness of child care in early education is a major gap, Schonfeld said. The ongoing concern is that schools, child care, and early education centers are not sufficiently prepared to recover promptly from natural disasters and they remain potential soft but high-impact targets for terrorism.

Elementary and Secondary Education

Moving to Section 7 of the NCCD report, Schonfeld conveyed the commission’s concerns about the limited funds available to improve the preparedness of schools and school districts. The recommendations in this section call for DHS and FEMA to partner with the Department of

___________________

3Update: The Disaster Case Management Concept of Operations is now online; see http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/ohsepr/disaster-case-management (accessed November 1, 2013).

4The Head Start Emergency Preparedness Manual can be found at http://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/hslc/tta-system/health/ep (accessed November 1, 2013).

Education to provide additional “funding and other resources to support disaster preparedness efforts of state and local education agencies, including collaborative planning, training, and exercises with emergency management officials.” The commission also called for funding to states to “implement and evaluate training and professional development programs in basic skills in providing support to grieving students and students in crisis, and to establish state-wide requirements related to teacher certification and recertification” in these areas.

“School systems and their students remain unprepared to deal with disasters, whether natural or man-made.”

—David J. Schonfeld

The Readiness for Emergency Management in Schools (REMS) program was highlighted by the NCCD as a worthwhile mechanism for delivering grant funding to school districts for preparedness that should be expanded. However, funding for the REMS grant programs has been eliminated, and Schonfeld noted that there has been little progress toward the goal of implementing or evaluating the training and professional development of educators and other school personnel. At a recent White House event on school preparedness that was held after the school shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, there was a clear call from partners to reverse the cuts to the REMS grant program and to expand it substantially, as called for by the NCCD. Unfortunately, Schonfeld said, this is one area where ground has been lost, rather than progress made, and school systems and their students remain unprepared to deal with disasters, whether natural or man-made.

Child Welfare and Juvenile Justice

The NCCD made several recommendations aimed at ensuring that state and local child welfare agencies, juvenile justice agencies (and their associated court programs), and residential treatment, correctional, and detention facilities that house children become adequately prepared for disasters to minimize the impact of these events and to support rapid recovery. Recommendations 8.1, 8.2, and 8.3 call for an evaluation of current status; issuing of planning guidance; provision of funding, guidance, and technical assistance; and the establishment of minimal standards of preparedness. Schonfeld said that there has been some review of current preparedness, and the Department of Justice is preparing a pilot competitive grant program to states to support the

development of emergency preparedness plans for juvenile justice facilities. Still, there has not yet been sufficient response to remedy the gap as called for by the NCCD.

Sheltering, Housing, and Evacuation

The remaining three groups of recommendations in Sections 9, 10, and 11 address sheltering standards, services, and supplies; housing, including prioritizing the needs of families with children (including those with children who have disabilities or chronic physical or mental health needs) in temporary and long-term disaster housing; and evacuation, including reunification of children with their families after disasters.

HHS PROGRESS IN ADDRESSING CHILDREN’S DISASTER HEALTH NEEDS

The NCCD recommendations directed toward HHS fall into four key categories: behavioral health; MCMs; physical health, EMS, and transport; and child care and child welfare. To address these, ACF and the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) established the Children’s HHS Interagency Leadership on Disasters (CHILD) Working Group comprised of members from 18 HHS divisions. The working group was created to comprehensively integrate the disaster-related health and human services needs of children across HHS disaster policy, planning, and operations activities; to assess current capabilities and facilitate coordination at the policy and response levels; and to develop a set of recommendations to enhance departmental efforts (see Box 2-1). An overview of progress by HHS in the four areas was provided by Dan Dodgen, director of the Division for At-Risk Individuals, Behavioral Health, and Community Resilience in ASPR.5

___________________

5Dodgen referred participants to the Division for At-Risk Individuals, Behavioral Health, and Community Resilience website for further information: http://www.phe.gov/abc (accessed September 9, 2013).

Behavioral Health

Dodgen highlighted some of the key accomplishments thus far in the area of behavioral health, noting that these actions were taken in response to both the recommendations of the NCCD and recommendations of the National BioDefense Science Board.

BOX 2-1

Children’s Health and Human Services Interagency Leadership on Disasters (CHILD) Working Group Recommendations for Health and Human Services Action

Behavioral Health

- Develop and implement a concept of operations for disaster behavioral health.

- Implement internal, programmatic improvements to the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP).

- Leverage new/expanded health home and behavioral health benefits authorized by the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to promote health and resilience in children.

- Update HHS grants to improve integration among public health, behavioral health, and health care delivery systems.

- Enhance the research agenda for children’s disaster mental health.

- Promote and disseminate just-in-time training on children’s mental health for caregivers, professionals, and responders.

Medical Countermeasures (MCMs)

- Establish an integrated program team to advise the Public Health Emergency Medical Counter Measures Enterprise (PHEMCE) on pediatric and obstetric (OB) MCM priorities.

- Incorporate pediatric and OB-specific vulnerabilities in scenario and medical consequence modeling for requirements.

- Provide clarity in the regulatory pathway for pediatric MCMs (e.g., stockpiling, forward deployment, clinical guidance).

- Engage the pediatric MCM community on a regular basis.

- Continue and improve industry support for research and development of MCMs suitable to pediatric use.

- Include pediatric and OB expertise in the Public Health Emergency Research Review Board (PHERRB) to support data collection for assessing safety and efficacy of MCMs.

Physical Health, Emergency Medical Services (EMS), Transport

- Evaluate the recruitment and deployment process of the National Disaster Medical System Multi-Specialty Enhancement Team.

- Strengthen requirements for pediatric surge capacity within the Health Care Preparedness Program (HPP) and encourage HHS grantees to adopt the Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) pediatric equipment list for ambulances and other guidelines.

- Take a lead role in setting educational and operational standards for pre-hospital care, particularly for children.

- Convene stakeholders to assess capabilities and address gaps for large-scale pediatric patient movement.

- Train NDMS personnel in pediatric disaster medicine to ensure basic clinical skills.

Child Care and Child Welfare

- Implement and promote the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) Information Memorandum that provides guidance to Child Care and Development Fund Lead Agencies in developing, exercising, and maintaining comprehensive emergency preparedness and response plans for child care.

- Develop a cross-regional review of child welfare disaster plans to identify strengths, areas for improvement, and targeted technical assistance.

- Make available additional outreach and training efforts for states to increase their understanding of the Disaster Case Management program.

- Ensure children and others with access and functional needs are included in relevant disaster services trainings.

SOURCE: Dodgen presentation, June 10, 2013.

First, HHS created and implemented a Disaster Behavioral Health Concept of Operations6 designed to provide coordination and guidance for federal-level behavioral response. As a result, children’s behavioral health is now part of every HHS response and recovery to disasters. For example, HHS provided support in response to the Newtown, Connecticut, shooting, Hurricane Sandy, and the Joplin tornadoes through the

___________________

6The HHS Disaster Behavioral Health Concept of Operations is available at http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/abc/Documents/dbh-conops.pdf (accessed September 9, 2013).

CCP, which sent trained crisis counselors into the community and schools to work with children.

To build capacity, ASPR leadership and NDMS responders have been trained in psychological first aid, the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps includes psychological first aid in all of its field training activities, and a 6-hour, interactive, online psychological first aid course available through National Child Traumatic Stress Network.7

In 2012, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) launched the Disaster Distress Helpline (DDH), the first hotline dedicated to providing disaster crisis counseling. The DDH offers support via telephone and Short Message Service (SMS) text, and hosted a Twitter chat on helping children and teenagers cope after disasters. The line is always active and ready for use, Dodgen explained, and capacity can be increased as events happens. Dodgen commended SAMHSA for making the disaster distress line readily accessible via forms of communication that are popular among adolescents (e.g., texting and Twitter).

Medical Countermeasures

We are beginning to make some real strides in moving forward the MCM enterprise for children, Dodgen said. For example, a pediatric and obstetric integrated program team was established to provide guidance to PHEMCE and prioritize gaps related to pediatric and obstetrical needs. There are now a number of pediatric MCM initiatives under way. In May 2013, for example, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) awarded a contract for the development of the antibiotic solithromycin for the treatment of children infected with anthrax, tularemia, or community-acquired bacterial pneumonia. Clinical studies have also been funded by the National Institutes of Health and BARDA to support a pediatric indication for midazolam to treat nerveagent seizures, and they should be widely distributed within stockpiles for children once approved. Though, as benzodiazepines (midazolam family) are commonly used for the treatment of seizure disorders in children, clinical studies on drugs that are not used as often or where effects are less clear could also be illuminating. In addition, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pediatric Trials

___________________

7The psychological first aid course is available at http://learn.nctsn.org/course/category.php?id=11 (accessed September 9, 2013).

Network plans to conduct 16 trials in the next 5 years that could enhance pediatric labeling of MCMs. There are also activities aimed at addressing the unique challenges of developing MCMs for children. For example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration held a public workshop on the Ethical and Regulatory Challenges in the Development of Pediatric Medical Countermeasures.

Physical Health, EMS, and Transport

Dodgen highlighted several accomplishments in the areas of pediatric physical health, EMS, and transport. The NDMS has developed the capability to deploy pediatric specialists to augment traditional response teams. The intent is to have people with unique expertise who may not need to respond to every emergency setting, but who are available when needed. To help address pediatric patient movement, ASPR hosted two workshops with pediatric transport stakeholders and additional workshops are planned. To aid reunification, one outcome of the Pediatric Disaster Preparedness Curriculum Development Conference convened by the National Center for Disaster Medicine and Public Health was an online module, “Tracking and Reunification of Children in Disasters: A Lesson and Reference for Health Professionals.”8 The ASPR HPP hosted a technical assistance webinar in June 2013 for HPP grantees and health care coalitions on integrating pediatric disaster management into health care system preparedness and medical surge.9 Approximately 400 people dialed in to participate in the webinar, and the archived webpage received 3,000 visits in the first month it was available. A second webinar focused on pediatrics is scheduled for May 2014 through the HPP at ASPR.

These are just a few examples of current programs, and Dodgen noted that the goal is not to simply create more federal mechanisms and federal projects, but to involve the stakeholders and people at the local level who will ultimately implement the programs.

___________________

8Module is available at http://ncdmph.usuhs.edu/KnowledgeLearning/2012-Learning1.htm (accessed September 9, 2013).

9The webinar is archived at http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/abc/Pages/webinar-resources-130620.aspx (accessed September 9, 2013) along with all of the resources identified, from both federal agencies and nongovernment partners.

Child Care and Child Welfare

There is a lot of activity on child care and child welfare happening at ACF right now, Dodgen said. For example, ACF has trained all of the nation’s State Administrators for Family Violence Prevention and Services on disaster preparedness, including attention to the needs of children exposed to domestic violence. ACF has also trained Head Start executives in preparedness planning. ACF recently collaborated with state and NGO partners via Child Care Task Forces and Coalitions following the Joplin tornadoes and Hurricanes Isaac and Sandy to assess the impacts to systems serving children and to promote children’s resilience and recovery. (Efforts toward improved child and family welfare during disaster recovery are discussed further in Chapter 8.)

Next Steps for HHS

HHS has been responsive to the recommendations of the Commission and other stakeholders, and has covered a lot of the basic areas, Dodgen said, but there is still work to be done. The CHILD working group has prioritized three additional areas of focus for 2012-2013: children with special health care needs and other subpopulations of children traditionally under-represented in planning efforts; pregnant/breastfeeding women and neonates; and enhancing inter-departmental and NGO collaboration. The working group plans to submit its second progress report to HHS leadership at the end of 2013. In closing, Dodgen said that Assistant Secretary Lurie and ASPR are committed to ensuring that children are integrated into all emergency preparedness, response, and recovery efforts. HHS policies and programs will continue to emphasize and address the disaster health and human services needs of children and families. He stressed that, in the face of the sequester budget challenges, there is no longer room for isolated projects. Collaboration across federal agencies and with outside stakeholders is essential.