7

Local-level Economic and Social Consequences

P. A. Bolton, Battelle Institute, Seattle, Washington

INTRODUCTION

While not a major focus of the North American media, the earthquakes that occurred in northeastern Ecuador on the night of March 5, 1987, were of considerable significance within Ecuador. At the national level, the country's already deteriorating economy suffered a major blow when Ecuadorian oil production was disrupted by earthquake-related damage to the Trans-Ecuadorian pipeline. According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, 1987), the Ecuadorian oil fields had accounted for about 60 percent of the nation's export earnings. Thus, Ecuador's ability to meet its internal operating costs and to make interest payments on its foreign debt were severely impaired. Within a week after the earthquakes, the national government instituted several extreme economic measures, including suspension of the external debt payment to private banks, increased fuel prices, a national austerity plan, and a price freeze on selected essential goods.

The earthquake's social consequences and accompanying demands for response and recovery assistance were relatively unusual with respect to their variety and geographic scope. Damage to the Trans-Ecuadorian pipeline resulted in both a major reconstruction cost and a major loss of national revenue. The damage to housing was spread over a large area and distributed mostly among households of limited resources. The loss of a major transportation route created problems for thousands of people who otherwise suffered no direct damage.

At the most basic level, the tremors were particularly frightening to the populations most directly affected. No earthquakes of a similar magnitude had occurred in the affected area of the country for more than 30 years. The two major tremors, 3 hr apart, left in their wake not only a variety of

types of damage and social consequences, but considerable further hazard in the form of thousands of weakened buildings and the threat of additional landslides. Fortunately, within the next few months there were no substantial aftershocks, although about 20 of the thousands of aftershocks that occurred were perceptible to human beings.

This chapter describes the local-level consequences of the earthquakes that were noted during brief visits to three of the affected provinces. The observations reported here are mainly based on visits to several of the affected communities to view the damage, and on conversations with a variety of local officials, recovery program representatives, and local residents encountered along the way. A few documents and newspapers also were reviewed. The information from the communities was gathered approximately 16 weeks after the earthquakes, and thus refers mostly to consequences experienced and actions taken in the disaster-stricken areas up to the middle of June 1987.

The communities discussed here are located in regions of Ecuador known generally as the Oriente and the Sierra (Figure 2.1). The Oriente extends eastward from the flanks of the Andes and forms part of the Amazon Basin. Damage to the communities in the Andean region, known as the Sierra, occurred mainly in the relatively densely populated central valley N of the capital city, Quito.

As described in earlier chapters, the mass-wasting phenomena that resulted from the earthquakes occurred in the mountainous western fringes of the Oriente in the vicinity of Reventador Volcano (Figure 1.1). The communities visited in this region (Figure 1.1, Figure 1.2, Figure 4.3) included Lago Agrio at the northern edge of the affected area, Baeza at the southern end, and some smaller villages between Baeza and the bridge site where the Salado River joins the Coca River. These communities are located in Napo Province.

In the Sierra, where damage was mostly limited to specific types of structures affected by ground shaking, exploratory visits were made to parts of the capital city of Quito, to the town of Tabacundo, the village of Olmedo, and the city of Ibarra and its environs ( Figure 4.3). These communities lie in northern Pichincha Province and in southern Imbabura Province (Figure 4.1). Carchi Province (Figure 4.1), N of Imbabura Province, also was considered part of the disaster area, but was not visited.

IMMEDIATE CONSEQUENCES AND EMERGENCY-RESPONSE ISSUES

There was little major damage to structures in Quito, although observers reported some rather spectacular fireballs that accompanied the consequences to the power system of the first strong ground movement. Within a few hours, the electricity and phone service were back to normal. Later damage

assessments revealed minor cracking in various buildings around the city, and somewhat more serious damage to several colonial-era churches and cathedrals in the oldest section of Quito, as well as to some of the older houses.

The earthquakes were felt with sufficient intensity in Quito to alert national and international agencies to the possibility of serious consequences and to the need to begin an immediate assessment of the situation. The various environmental clues led to some degree of uncertainty in the first few hours. For example, preliminary damage assessments had to be reexamined once the second and more damaging quake (Ms=6.9) occurred 3 hr later. Also, there was initial concern, because of the location of the epicenter and reports of landsliding, as to whether a volcanic eruption had been involved, or might be expected. Secondly, even before dawn, because of the evidence of landslides that resulted in flooding along the Coca and Aguarico rivers and in a broken oil pipeline along the Coca, attention of emergency responders and assessment teams was initially focused on the greatly affected but sparsely populated area immediately E of Reventador Volcano ( Figure 1.2). The Ecuadorian military detachment in Lago Agrio was first on the scene on Friday, March 6, beginning its reconnaissance and search-and-rescue missions at dawn.

On Saturday, March 7, assessments were made by U.S. experts. Also by Saturday, the extensiveness of the damage to houses in the Sierra had become evident. For the most part in the Sierra, damaged houses had not collapsed immediately, and there was no loss of life or need for search-andrescue efforts.

The major effects were determined to be of three general types:

-

Direct effects of the landslides, debris flows, and flooding to the infrastructure in the area, including damage to roads and bridges and in particular the Trans-Ecuadorian oil pipeline and the parallel Poliducto gas line. This damage in turn had secondary effects on both the local and national economies.

-

Direct effects from the ground shaking on housing and some public buildings in communities N of Quito, and also to some extent in the Oriente.

-

Indirect effects on the population of Napo Province that no longer had land access to the rest of the country, as a result of the only road from the town of Lago Agrio to the Sierra region and the capital city of Quito being impassable.

This chapter provides a brief review of the emergency-response-related issues and of the most significant aspects of the emergency period as they differed in the Oriente and the Sierra. It then describes emerging long

term impacts observed in June 1987, followed by sections on the economic and social impacts and recovery activities observed in the Oriente and the Sierra.

THE EMERGENCY PERIOD IN THE ORIENTE

Beginning with the effects on Napo Province, the most evident direct physical damage from the earthquake was on the flanks of Reventador Volcano and on the floodplains of the drainage systems in this mountainous area. Virtually all of the loss of life associated with the event occurred in Napo Province. The most common estimate of the number of deaths related to the earthquakes is about 1,000. Those who lost their lives were caught by the landslides, or were swept away in the rivers swollen by the debris flows of saturated soil, rock debris, and vegetation from the steep volcanic slopes. These victims typically were residents of plantations or small settlements in the hills and on the floodplains in the area between Baeza and Lumbaquí (Figure 7.1).

In general, the area has only recently been settled by farmers who came there as part of the national agrarian reform and colonization program. Previously, the area was inhabited by various indigenous groups that to a

FIGURE 7.1 Typical preearthquake dwelling along the Trans-Ecuadorian pipeline and highway near Reventador Volcano. (1978 photograph by S. D. Schwarz.)

great extent have been pushed farther into the jungle as land is provided to the new settlers. Estimates of the numbers of settlers that were killed or missing as a result of the earthquake vary considerably because there are no reliable data on how many people were living in the area affected by the landslides, and it is assumed that many bodies have not been recovered from the rivers. No specific information was found on whether or not indigenous settlements were included among those destroyed.

Those who were fortunate enough not to be caught in the landslides and debris flows were stranded if they were located on the N side of the Coca River between the bridge at the confluence of the Salado and Coca rivers and the bridge over the Aguarico River. Most of those who were stranded were evacuated by helicopter in the first day or two after the earthquakes, because it was believed that the area was too hazardous for them to remain.

These evacuations and the search-and-rescue operations were carried out by the Ecuadorian Air Force and Special Forces. Provisional shelter was found in convents, schools, and private homes until tent camps could be established in Lago Agrio and in the villages between the Salado River bridge and Baeza. It generally is estimated that around 4,000 to 5,000 people were evacuated. About 500 to 1,000 people eventually were taken to camps in Quito, and about 1,000 stayed in the camps in the Oriente. It is likely that the majority of the evacuees moved in with relatives or friends near the disaster area or in other parts of Ecuador. Some families stayed in Lumbaquí and other nearby settlements, but had to have supplies airlifted across the Aguarico River to them. Eventually this airlift was replaced by canoes and, for a short time, a footbridge (which subsequently washed out). Airlifts for supplies were coordinated by an emergency operations committee that met daily in Lago Agrio, and were carried out by the Ecuadorian Air Force. Lago Agrio itself did not suffer flooding or earthquake damage.

In the area most heavily damaged by the landslides, much vegetation was lost from the mountainsides, leaving the area even more vulnerable to future landsliding. Plantations, grazing land, and other agricultural developments, as well as livestock, also were destroyed by landslides, debris flows, and flooding. Many vehicles were lost or damaged, and others were stranded in the area until the road could be reopened. This caused hardship for survivors who depended on the vehicles for their livelihood.

The sediment in the rivers from the landslides and debris flows did considerable damage to fisheries for great distances downstream. Although about 100,000 barrels of oil spilled into the river when the pipeline was broken, any environmental effect it may have had was overwhelmed by the effects of the sediment and other debris in the water. The destruction of the fish population undoubtedly had negative consequences, in particular to indigenous groups engaged in subsistence fishing. There also were reports

of sediment and other contamination in the rivers causing short-term health problems and making the water unusable until the rivers cleared.

Some tourism was said to have been affected for a short time by the debris load in the rivers, since one of the attractions in eastern Napo Province is boat excursions along the jungle rivers. However, most of this activity is centered in towns that are farther E or S; thus, the economic effects, if any, were not felt in Lago Agrio.

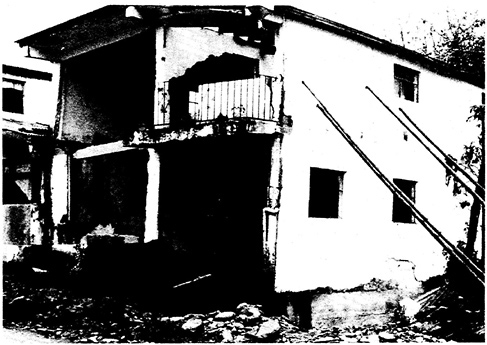

In the small towns S of the area most damaged by landslides, some dwellings were damaged by the groundshaking. In particular, houses constructed of concrete blocks suffered the greatest damage, since most of them had been poorly constructed. To a great extent, these were the homes of people who had prospered enough to move out of the more traditional wooden houses. A few wooden houses also suffered some degree of distortion, or had damage to their concrete foundations. Baeza, the largest town S of the landslide area, presented the most significant example of extensive damage to concrete block homes ( Figure 7.2), as well as to some wooden structures.

Although no long-term camp for evacuees from the landslide zone was established in Baeza, many of the town's own residents were dislocated from their damaged or collapsed homes and had to find other lodging or

FIGURE 7.2 Damaged concrete-block dwelling in Baeza, Napo Province.

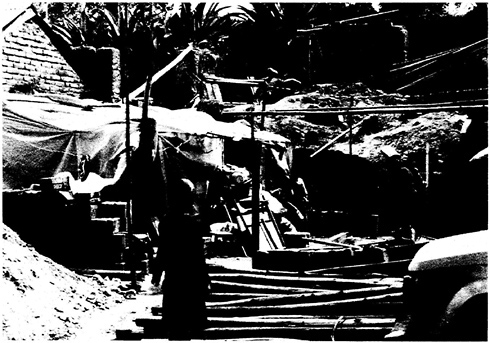

FIGURE 7.3 Tents for refugees from the landslide/flood zone, placed in the town square of Quijos.

make temporary shelters near their damaged homes. Several of the smaller towns became locations for tent camps that housed evacuees from the landslide area who had nowhere else to go, or who preferred to remain near their landholdings (Figure 7.3). An Italian emergency medical response team established a field hospital in Baeza immediately after the disaster, which they later donated to the community.

THE EMERGENCY PERIOD IN THE SIERRA

The damage caused in the communities N of Quito was characteristic of what most typically happens in an earthquake event like that of March 5. Damage patterns were related to the distribution of buildings with certain characteristics of construction design and quality, with some variation depending on the type of soil and the orientation of the structures in relation to the epicenter.

The most extensive damage in the Sierra occurred to houses constructed of adobe bricks or tapia (mud poured into molds and then sun-dried in place to form walls), and particularly to those constructed according to traditional building practices in the rural areas. Consequently, the bulk of the house

holds directly affected were those in the lowest income class. These households typically were located in the more marginal barrios of the larger towns or in the predominantly Indian villages and rural settlements. To some extent, other types of houses and public buildings also were damaged, particularly those constructed in the 19th century or with improper construction practices.

For the most part, the houses did not collapse outright, although there may have been failure of a wall or two, or the collapse of a portion of a roof. No deaths were reported as a result of building collapse. However, the houses that were damaged were greatly weakened, and many collapsed later or were purposely demolished.

Many schools were damaged or destroyed because they had been constructed in the same manner as the houses. A much smaller proportion of community health-center facilities sustained major damage, since these were more likely to be newer buildings than were the schools. In some instances, the health centers served as public shelters in the first week or so.

Although tremors had been felt on occasion in the Sierra in past years, none has jolted the area with the intensity of those occurring on March 5. We were told that residents of the villages exhibited extreme fear. Many engaged in fervent prayer, because they viewed the event as punishment for sinful behavior. However, these typically were secondhand reports, making it difficult to determine whether they were accurate descriptions of the villagers' behavior or whether the behavior of a few individuals was being attributed to the rural population as a whole in order to underscore the local impact of the event.

Health-center patients in Imbabura Province were screened for symptoms of mental health problems 10 to 12 weeks after the earthquakes. Although the data were not yet analyzed as of June 1987, the preliminary impression of researchers at the Ministerio de Salud Pública, División Nacional de Salud Mental (Ministry of Health, National Division of Mental Health) was that about 25 percent of the victims interviewed exhibited emotional problems, to a great degree related to the earthquakes.

After the earthquakes, many people chose to sleep outside their homes for several weeks, even though the weather turned rainy and cold the day after the tremors. This rational adaptation is common in areas hit by damaging earthquakes. As in other earthquake situations, the vulnerability of many of the dwellings was apparent, even without deaths having occurred, and mild aftershocks could be felt for many weeks, creating doubt about whether or not the worst had yet happened. Even people whose homes were not damaged were reported to have slept outside their houses for some time.

More than 1,000 tents were eventually supplied to families in the affected area in the Sierra. Some families slept in public buildings, such as health centers, until other shelter could be prepared. Many other families

improvised shelters near their damaged dwellings, using plastic sheeting provided to victims by assistance agencies.

Some tent camps for refugees were established; in other instances, tents or shelters made of plastic sheeting were placed on private lots adjacent to damaged dwellings. Emergency-period activities and distribution of relief goods most commonly were coordinated by the provincial staff of the Defensa Civil de Ecuador (Ecuadorian Civil Defense), although various observers noted that the organization was not as yet very skilled in such activities. Within a few days after the disaster, there was some distribution of clothing and food, but these activities were of short duration, and done in many instances without any systematic attempts to identify who were victims and who were not. The aid distribution was handled differently in different locations; for example, in some places the distribution involved only Civil Defense, at others a priest or minister. It was apparent that most of the disaster-assistance activities during the emergency period were conducted in the more urbanized areas.

Three refugee camps were established on the periphery of Ibarra, the largest city in Imbabura Province, providing temporary housing for residents whose homes were destroyed. These camps apparently were established and maintained under the direction of a local physician, who donated his time to this effort and to tending to the health needs of victims for the first month after the disaster. The tents came from outside Ecuador and were distributed by Civil Defense to the local Red Cross chapter to establish the camp. This physician, working with Red Cross emergency medical assistants (socorristas) he was training, planned and established the camp and the procedures for feeding the refugees and maintaining sanitary conditions. The National Guard handled discipline and security. The physician remarked that he knew there were books available from international organizations to guide in the establishment of refugee camps, but he had great difficulty in obtaining them quickly enough to be of any use. He eventually obtained some by going to Quito and paying for them himself, but this was after most of the initial work had been done to establish the camp.

Little mention was made of injuries suffered in the earthquakes. However, the physician in Ibarra noted that respiratory diseases were common among the persons who lived in the tent camp or who had been living outside their damaged houses in the rain and cold.

Mention was made by some of disruption of tourism in the Sierra. Locals observed that the number of tourists visiting Indian markets near Cayambe and Ibarra diminished somewhat after the earthquakes, but only for a short time. Also, one person noted that some people believed that the tourism bureau had made efforts to minimize reports of damage from the region, so as to minimize economic consequences to resorts and mar-

kets. The concern was expressed that by minimizing reports of damage, the chance for the area to receive available and necessary disaster assistance was in turn affected. This dilemma has been noted in other disasters and warrants further study in future disasters.

EMERGING LONG-TERM IMPACTS

When considering the longer-term impacts that seemed to be emerging in the communities visited, it is important to recognize the overall economic context in which these were occurring. Although the opening of the Amazonian oil fields many years before had given an important boost to the economy of the country, Ecuador had at the same time become very dependent on oil revenues. Thus, when oil prices fell in 1986, the annual economic growth of the country dropped to below 2 percent, a large fiscal deficit was incurred, and the trade surplus fell (ECLAC, 1987, p. 2).

Including the anticipated 6-month curtailment in oil production while the Trans-Ecuadorian pipeline was being repaired, the total cost to the country was estimated soon after the disaster to be about $1 billion (ECLAC, 1987, p. 26). At about the same time as the March 5 earthquakes and resulting landslides, widespread flooding (unrelated to the earthquakes) occurred in the vicinity of Guayaquil (Figure 1.1); considerable infrastructure was damaged by all of these catastrophes, placing additional demands on the national budget. The reconstruction needs created by the disasters only added to Ecuador's already serious economic difficulties, and rather specific financial strategies were needed to try to deal with the situation.

Under the circumstances, recovery projects designed to help generate local currency are important to consider. National and international strategies for doing this have not been examined in this quick reconnaissance study but, where implemented, warrant evaluation as to their effectiveness and transferability into other postdisaster settings.

To the people in the affected communities, who had already begun to feel the consequences to their pocketbooks of the national economic problems before the earthquake, there was some skepticism that the economic problems and national austerity measures attributed to the earthquake did indeed originate with it. It is difficult to say which of the economic problems evident at the community level after the disaster might have been experienced even without an earthquake, as the national government grappled with its longer-term problems. The natural disasters certainly exacerbated the situation.

The earthquake damage had affected for the most part persons who already were experiencing difficult economic circumstances. Much of the damage occurred in rural areas that had very limited infrastructure and were lacking in basic services even before the earthquake. Thus, the mingling of

reconstruction issues and development issues could be expected. For example, one demonstration of dissatisfaction with the progress of disaster recovery was covered in the Quito newspapers in June (Hoy, June 16, 1987; El Comercio, June 17, 1987). The reports described a contingent of local government officials and residents marching to Quito from the capital of Napo Province to ask for additional reconstruction assistance; however, the request was more general than for just things that would allow reconstruction of the disaster-stricken communities to predisaster conditions. Here again, no in-depth analysis was attempted of this aspect of the recovery process, but the relationship between reconstruction and development is a topic of interest for designing disaster assistance in developing countries (Bates, 1982; Cuny, 1983).

Increased prices for staples were part of the overall economic changes that individuals reported in all parts of the disaster area. Gasoline was rationed for a short time after the earthquakes. The price of gasoline increased by about 80 percent at the time, and was still at that level in June 1987. This in turn affected bus fares and the costs of transportation for agricultural produce and other goods. The price of cooking fuel used in urban areas also increased. People reported that the price of some, but not all, food items increased. There also was a shortage of sugar beginning in June, but this was attributed to actions on the part of the sugar producers in order to raise prices.

Many people indicated skepticism about the reasons for the price increases and said that the earthquake was being used as a pretext for the government to institute economic measures it had planned to take anyway. However, the fact that the nation could not meet even its own internal petroleum needs after the pipeline breakage cannot be ignored in relation to increases in fuel prices.

RECOVERY PROGRAMS AND IMPACTS IN THE ORIENTE

By mid-June 1987, little had been accomplished in the way of reconstruction in Baeza and the other communities along the road toward the Salado River bridge. The people in Baeza who had been dislocated from their homes were for the most part either living in shelters on their property or sharing homes with relatives. Some people had apparently left the area, but we were told that many people in Baeza had government jobs and thus their incomes had not been affected, even though they may have had housing problems. It is likely that the restaurant and hotel business had slowed somewhat with the reduced traffic along the Baeza-Lago Agrio highway.

The tent hospital that the Italian medical team had donated was being operated by the Ecuadorian Ministry of Health, in order to provide free

health care that had not previously been available in the area. There was a private Catholic hospital in Baeza as well. The tent hospital was staffed with two nurses who lived in Baeza and two doctors who commuted from Quito. The plan was to eventually move the health facility into a permanent building. One of the nurses noted that the main malady they were treating was scabies, which was rampant in the households that had been living in tents for the last 3 months.

A housing loan program offered by the Banco Ecuatoriano de la Vivienda (Ecuadorian Housing Bank) was just being started in the Oriente as of the middle of June 1987. The plan was to have four technical representatives of the bank. These representatives would visit residents, offer loans, and give technical advice on construction. In addition, there would be four social workers, who would check on the families' abilities to qualify for the loans, and would help them find solutions for any financial problems that might arise later. (This loan program is discussed further in the next section.)

In the town of El Chaco (Figure 1.1 and Figure 4.3), we were told that Civil Defense officials were that same day giving out a bag of cement to each family having a damaged house, but few other details about the program were known. Several damaged buildings were evident in the community, but little visible construction or repair work was going on. However, it had been raining daily, which might account for the lack of such activity in the communities.

In talking to a few people in the towns of El Chaco and Quijos (on the Quijos River, 4 km downstream from El Chaco), it was evident that, in the communities with evacuee tent camps, there were three distinctions used for disaster victims: (1) people from other towns who lived in the camps, (2) people who lived in the town whose houses had been badly damaged or destroyed, and (3) people who had not suffered damage. Those in the last group had not received any type of disaster assistance, but often were impacted in some indirect way. Impacts reported included reduced income as a result of a voluntary reduction in agricultural production because it was not possible to transport the agricultural products to market, a reduction in income from food sales during the time that disaster victims were receiving free food, and reduced business in general because the destruction of the Trans-Ecuadorian highway east of the Salado River reduced the road traffic to that point, and many people had left the area to try to find employment opportunities elsewhere.

It was reported that the crews that had formerly operated the pumping stations along the pipeline had mostly left the area. However, there was a construction camp in the town of Quijos for the workers who were replacing the bridge across the Coca River at Lumbaquí (Figure 1.2). One person observed that these workers were paid very good salaries, but described the

consequences of this in negative terms because of the workers' disorderly behavior when off duty. However, there undoubtedly were some local benefits from having these jobs and salaries in the area.

Other comments were made by local residents about the relations between various groups, for example, between evacuees and residents, Catholics and Evangelists, victims and nonvictims, and people with money and people without. These comments suggest that further in-depth study might indicate that these communities have fairly low social cohesion. The different social character of people of the Oriente compared with those of the Sierra was mentioned by more than one observer.

In general, aside from the original indigenous inhabitants of the Oriente, who were not encountered during the visit to the disaster area, the populations in the towns and on the plantations were fairly recently arrived, and typically had left some other part of the country in order to seek economic opportunity as colonists to this area. Thus, these residents were not likely as yet to have long-term attachment to the land nor to have extensive and strong social ties to others in the area. One local storekeeper remarked that, right after the earthquake, the people had helped each other, but now things were “back to normal.”

Another notable aspect of the earthquakes' effects on the Oriente was the impacts in Napo Province created by the loss of the Salado and Aguarico river bridges. First, the inaccessibility of the land along the approximately 67-km stretch of road between these two bridges created problems for the surviving farmers and plantation owners who had been evacuated from the area. Besides the washed-out bridges, the roads in the area between the bridges were blocked by landslides and by flood damage in many places, and the threat of further landsliding was high, making the area both difficult and very risky for resettlement at that time, even if it could be served by air or boat. Secondly, a large proportion of the 75,000 inhabitants of Napo Province were effectively cut off from the rest of Ecuador by the damage to the road between Baeza and Lago Agrio.

The effects on the inhabitants of the town of Lago Agrio (Figure 1.1) and of the areas to the N and E in Napo Province were for the most part indirect. There was little significant direct damage from the groundshaking of the earthquake in the eastern part of Napo Province. However, agricultural producers in the region suffered significant economic impacts as a result of not being able to transport their crops to market. For example, it was estimated that the postearthquake production losses from abandonment of land or lack of access to markets amounted to about $7 million (ECLAC, 1987, pp. 18-19). This estimate was based on the assumption that land access would be reestablished by the end of June, which it was not. The main link with the rest of the country as of June 1987 was by air, a means of transportation that is too expensive for most agricultural products.

Without income from agriculture in the area, retailers and services in turn suffered from reduced business volume. People familiar with Lago Agrio prior to the earthquakes observed that the number of retail stalls on the main street had greatly declined, and also believed that people were leaving the area increasingly to look for work elsewhere.

An inquiry into the impacts on employment due to the drastic reduction in oil production revealed that the workers at the CEPE-Texaco installation near Lago Agrio figured little in the economy of the town, both before and after the earthquake. The CEPE-Texaco “camp” operated much like an offshore drilling rig, with workers sleeping in dormitories and eating in the company dining hall for several days at a time, and then being flown by the company back to their homes in Quito when the shift changed. The Texaco workers for the most part were shifted from production to maintenance work while the pipeline was being repaired.

With the exception of the indigenous groups, the settlers in the area are dependent on receiving food staples and gasoline from outside Napo. Also, major medical services and some kinds of business services can be obtained only in the larger cities elsewhere in the country. The airlink that existed in June 1987 was used mainly for passengers and for bringing in these staples. The air service was provided by the national airlines, and created considerable uncertainty for persons trying to use it to leave the area. There were only a few flights a day, despite the high demand for the service. The fare could be paid in advance, but seats could not be reserved; thus, hundreds of people stood in long lines for every flight out of the area, and they often could not get on a flight even after waiting a day or two.

One source indicated that products could be transported to and from eastern Napo region by motorized canoe up the Napo River, continuing to Lago Agrio by bus from the town of Coca (also known as Puerto Francisco de Orellana) (Figure 1.1). This apparently was the preferred means for bringing gasoline to the area, and could be used for taking products out. Another source suggested that considerable extortion was involved in getting transportation, air or water, for whatever products did leave the area.

The temporary lack of a road between Lago Agrio and Ecuador's other commercial centers made it difficult for many to maintain themselves economically while this condition existed. More importantly, there also was no specific information available to the inhabitants of the region as to when the road would be repaired. In fact, an alternative route (see Chapter 8) had been proposed and construction started, which if it were completed, would solve the problem of a transportation route for agricultural products, but also would have long-term implications for persons who owned land along the original route.

The question of whether the original road would be repaired or a new route established was not solved at the time of our visit to the disaster area.

Certainly, the existing route was located in a very hazardous area, which had been made even more hazardous by the earthquake-caused landsliding. Although the road and the Trans-Ecuadorian oil pipeline parallel each other much of the way between Baeza and Lago Agrio, and some type of access road is necessary for pipeline maintenance, it was noted that only a minimal road was necessary to service the pipeline. Thus, road construction efforts undertaken by Texaco and CEPE (Corporación Estatal Petrolera Ecuatoriana), the national petroleum company that operates the pipeline, in order to obtain access to the pipeline, would not necessarily result in a road of the same size and quality as existed before the earthquakes.

Continued uncertainty about the timing and location of a road to Lago Agrio made it impossible for the inhabitants of this isolated region to make informed decisions about the best course of action to protect their own personal economic interests. For the most part, about the only option for most was to leave the area in order to survive economically. This also was not a particularly promising option if it meant abandoning one's parcel of land.

Another type of issue existed with respect to the question of access to landholdings along the Baeza-Lago Agrio road and access to Lago Agrio. First, some settlers (about 80 families) who had been farming in the landslide/ flood zone had expressed interest in relocation. Among the reasons for their wanting to do this was that the former land was now ruined, or that they could not wait any longer to have land to work, or that they considered the area too hazardous to return to. However, there were difficulties in obtaining other land in the Oriente that could be made available to them. INCRAE (Instituto de Colonización y Reforma Agraria Ecuatoriana), the Ecuadorian colonization and agrarian reform agency, indicated that there were major problems to be solved, both for the families that were willing to stay in the disaster area to farm and for those who wanted to be relocated.

In order to obtain new land in northeastern Ecuador, progress needs to be made in agrarian reform. Whether families are returned to their preearthquake plantations or resettled onto new lands, resources are needed to provide the necessary infrastructure of roads, bridges, schools, health centers, and so forth. For either solution to be accomplished, several national-level agencies will have to work in concert to bring it about in a timely manner. Thus, at least 200 families who had farmed the land between the Salado and Aguarico River bridges remained in limbo about their futures 4 months after the earthquakes, many living without a permanent dwelling or income.

RECOVERY PROGRAMS AND IMPACTS IN THE SIERRA

In the Sierra, many families with badly damaged or demolished houses constructed simple shelters on their lots, and in June 1987 were preparing to rebuild their houses. Others reportedly had doubled up with relatives for

the short term until they could rebuild. Some of the housing construction activity was undertaken with technical supervision and some was not. Because there was no mechanism for condemning dangerous buildings, there also was concern that many families continued to live in houses that were even more vulnerable to future earthquakes than they had been before the earthquakes. The dilemma of reconstructing communities in a timely manner versus taking the time and resources to provide safer housing and other facilities has been observed in many other disasters (Haas and others, 1977; Bates, 1982).

The reconstruction period provides one of the best opportunities for upgrading housing and making it safer, because interest and awareness are high. In the damaged villages of northern Pichincha Province (Figure 4.1), the provincial office of Civil Defense coordinated housing reconstruction with the Ecuadorian Housing Bank and other groups. They developed a plan for the reconstruction that focused mainly on helping the poorest victims.

A map of the projects in Pichincha Province showed three different types of projects: (1) communities in which housing reconstruction was supported by Civil Defense, (2) communities supported from international assistance organizations (“outside the [national] plan”), and (3) communities that had been designated for a project, but for which there were no funds as yet. The projects to be implemented jointly by Civil Defense and either the housing bank or private contractors were slated to start in October 1987. For these projects, construction materials were to be given to the homeowners who were to provide the labor, with technical assistance from Civil Defense or the housing bank. Necessary machinery was to be loaned by the municipal government. At the time of the author 's reconnaissance visit, it was not possible to say to what extent any of the planned housing programs would be implemented or in which villages this would occur.

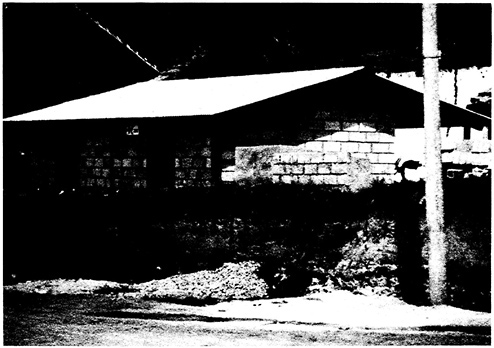

The town of Tabacundo (Figure 4.3) provided one example of a community in which many stages of housing reconstruction could be seen at one time. The temporary housing being used ranged from crude, makeshift shacks, to tents from foreign donors, to small houses of wood slabs. Many lots had been completely cleared of the damaged structures, and construction was beginning (Figure 7.4). Some residents were rebuilding with their own resources, while about 120 households had received metal frames, donated by a German organization, to provide support for walls made of brick infill. Other people were building more traditional adobe buildings. The community was given a machine for compacting the adobe bricks to make them more seismic-resistant, and we were told that technical assistance was available in the community from Ecuadorian agencies. The people could request certain building materials from Civil Defense; these materials were delivered by trucks provided by the municipal government.

FIGURE 7.4 Temporary dwelling of plastic sheeting used as a residence while family builds a new home using a metal frame, Tabacundo, Pichincha Province.

In most small Andean communities, the population of Indian descent typically uses the traditional social practice of the minga, or ad hoc work group, to complete community projects. A specific project is selected and a work group, sometimes involving most of the people in the village, is formed to complete it. In Tabacundo, the minga tradition was being used in the reconstruction of housing. For example, a minga work group was observed making adobe bricks using a new compacting device (Figure 7.5).

Various interviews indicated that there was some controversy about what approach to reconstruction has the fewest drawbacks. Governmental officials claimed that the Indians, even though they are primarily farmers, had sufficient time to also work on the reconstruction of housing in their communities. Furthermore, the use of the residents to provide the construction labor makes the projects less costly and supposedly gives the residents a stronger sense of ownership for reconstruction activities. Other observers felt that the construction work cut into the farming work and that this might lead to problems in the future if food production was inadequate. Another argument was given by some that it was not the best idea to have the villagers do the construction, since houses not properly designed and constructed will be likely to suffer damage during future earthquakes.

FIGURE 7.5 Minga (traditional community work group) making mud bricks using a brick-compacting machine that had been donated to the community, Tabacundo, Pichincha Province.

The provision of technical assistance and instruction is a means of counteracting the potential that local people will be unfamiliar with appropriate building design and construction procedures. The reconstruction plans of the national Civil Defense office and the Ecuadorian Housing Bank included the provision of technical assistance and instruction to community residents. Also, books with simple pictures and descriptions on how to repair or to build seismically resistant adobe houses were available for distribution in the communities undertaking reconstruction. Two booklets that were available had been jointly prepared by the Junta Nacional de la Vivienda (National Housing Council) and the United Nations (Junta Nacional de la Vivienda and Centro de Naciones Unidas para Asentamientos Humanos-Habitat, 1987a, 1987b). A third one, on building with tapia (sun-dried mud slabs), had been published after the earthquake by the Centro Andino de Acción Popular (Andean Center for Popular Action) in 1987. It would be useful to document how widely distributed and used such booklets came to be, and how much technical assistance is necessary to support the use of such instructional materials.

Another example of a housing reconstruction program was observed in Imbabura Province (Figure 4.1). There, the League of Red Cross Societies

proposed after the disaster to build 1,000 houses to be donated to families selected as the most in need. The project was completed in 1987, with funds permitting the construction of 600 homes. Two designs were used: (1) an urban-style house with a metal frame and block infill and (2) a rural-style house with an exposed wooden beam across the center of the house from which harvested crops could be suspended, as was the custom. For this program, most of the construction materials were purchased locally, and local contractors were used to build the houses, with technical oversight by on-site specialists provided as part of the program (Figure 7.6). Program staff found many families incredulous that someone was going to give them a free house, and one of the initial tasks was to gain credibility with the potential recipients. The varying housing repair and reconstruction programs in the Andean highlands of Ecuador lend themselves to valuable study of the differential social impacts of the various approaches to involving inhabitants in the construction of housing.

In the Sierra, special attention was given to the preservation of various damaged buildings that were felt to have historical and cultural value to the country. They were considered important both for the citizens of Ecuador and for tourism. National funds were used for the repair of these

FIGURE 7.6 League of Red Cross Societies project house, urban style, Imbabura Province.

buildings, most of which were located in the cities of Quito and Ibarra. Governmental funds also were used to repair schools and health clinics, which were the responsibility of national agencies. However, most local public buildings did not come under any of these programs, and there was concern in the smaller communities about how these would be repaired.

Concerns also were voiced about the need for assisting displaced tenants. For example, in Ibarra (Figure 4.3), most of the families left in the tent camps after several months were renters at the time of the earthquakes. As renters, they could not receive assistance to repair their former housing, and usually had to relocate. The housing they had lived in was already the least expensive in the community, and there was very little affordable replacement housing in a market where demand for housing had increased. The tent dwellers had asked to keep their tents, but the local Red Cross chapter had declared its intention to reclaim the tents so they could be used in future emergencies. The camps could not be maintained indefinitely, and it was not clear what provisions were being considered, if any, for supplying housing for these victims.

A loan program to assist homeowners was designed by the Ecuadorian Housing Bank, based on the transfer of some of the bank's funds from regular housing loan programs to programs for earthquake victims. The loans were to be handled by local banks, and the borrowers were able to use the money for housing repair or reconstruction. Initially, it was anticipated that the program could help about 7,000 affected households. However, problems arose over whether or not the bank could use the funds in the manner specified for the loan program, and it appeared that far fewer loans would be possible. Also, as of June 1987, it appeared likely that the initially proposed housing grants for those with the lowest incomes would not be implemented.

The bank estimated that about 70 percent of the affected households had incomes too low to qualify for loans. About 20 percent of the affected households were estimated to have high enough incomes that they qualified only for the normal-rate loans, but many were likely to find the 19 percent interest rate unacceptably high. Only about 10 percent of the victims were estimated to be eligible for lower, preferential, rates established by the program. Thus, the program, as designed, was of limited value.

SUMMARY

At the time of our visit, 3 months after the disaster, the three major problems in the Oriente were: (1) repair of the oil pipeline, (2) deciding what rehabilitation activities were appropriate for the area so clearly identified as hazardous, and (3) deciding on the solution to providing a road that would connect the northeastern part of Napo Province to the rest of

the country. Of course, the problem of pipeline repair affected not only the Oriente, but the nation as a whole.

In the Sierra, the time was right for improving the seismic resistance of dwellings in the region. It remains to be seen whether or not the various programs for repairing and replacing damaged housing are implemented widely and effectively enough to significantly reduce the earthquake hazard for the inhabitants of the region.

The observations made in June 1987 revealed many areas in which lessons may be learned from this or future earthquake disasters in developing nations. Recommendations for further research include studies that address:

-

the extent to which technical assistance for construction, both in-person and in the form of written materials, reaches the affected population, and what factors contribute to its effectiveness,

-

the extent to which active efforts are made to distribute special instructional materials on handling the housing and health needs of disaster victims to persons at the local level who can assume responsibility for emergency programs,

-

the development of assistance approaches that emphasize generating local currency versus those that involve providing goods and services by outside organizations,

-

the economic and social consequences of various types of programs for repairing or replacing housing,

-

the relationship between various types of recovery assistance and the promotion of local or national economic development, and policy development for this issue,

-

the effects on reconstruction and relocation decisions of individual victims of providing, or not providing, information about government plans for replacement of infrastructure,

-

policies that help or hurt low-income renters, versus homeowners, whose dwellings were damaged or destroyed, and

-

ways in which the tourist industry can approach the dilemma of not discouraging visitors while not jeopardizing a region's access to assistance, and the extent to which disasters actually affect tourism.

REFERENCES

Bates, F. L. (ed.). 1982 . Recovery, Change and Development: A Longitudinal Study of the 1976 Guatemalan Earthquake, Final Report . Athens : University of Georgia .

Centro Andino de Acción Popular . 1987 . Construir la casa campesina: hagamos casas de tapia mas seguras . Quito .

Cuny, F. C. 1983 . Disasters and Development . New York : Oxford University Press .

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) . 1987 . The Natural Disaster of March 1987 in Ecuador and its Impact on Social and Economic Development . Report #87-4-406, United Nations , Geneva .

El Comercio (Quito) . June 17, 1987 .

Haas, J. E. , R. W. Kates , and M. J. Bowden (eds). 1977 . Reconstruction Following Disaster . Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press .

Hoy (Quito) . June 16, 1987 .

Junta Nacional de la Vivienda , and Centro de Naciones Unidas para Asentamientos Humanos-Habitat . 1987a . Como hacer nuestra casa de adobe . Quito , United Nations Project ECU-87-004 .

Junta Nacional de la Vivienda , and Centro de Naciones Unidas para Asentamientos Humanos-Habitat . 1987b . Como arreglar nuestra casa . Quito , United Nations Project ECU-86-004 .