Although most of the workshop focused on the actual human and environmental benefits and costs of the U.S. food system and dietary guidelines, the session summarized in this chapter revolved around the role of the food price environment and its impact on food and diet decision making. Workshop participants considered the role of weather and climate and the impact on commodity and food prices. Furthermore, participants discussed economic and marketing tools that will help consumers make food and diet choices that are healthier for both themselves and the environment.

Specifically, Richard Volpe, from the Economic Research Service (ERS), discussed the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) food price forecasting, emphasizing that most of the uncertainty of forecasted prices is due to unexpected droughts and other extreme weather events. Recent reversals in a couple of key long-term economic trends, such as the recent increase in commodity prices after decades of decreasing prices, are also likely due, at least in part, to extreme weather events. Still, despite increasing commodity prices, average food prices have been relatively stable and will continue to remain stable in the near future. Although average food prices have remained fairly stable, prices of some major food groups have fluctuated, with healthier foods (e.g., fresh fruits and vegetables) showing more price volatility than less-healthy packaged foods.

Barton Seaver, from Harvard University, encouraged workshop participants to expand their notion of sustainability and think not just about environmental impact but also resource and product use. There is no better

example of the opportunity for improved use of products, in his opinion, than the Peruvian anchoveta fishery. He encouraged a reexamination of U.S. fisheries and a consideration of ways to use some of the many other fish and shellfish in the sea. For example, although cod is a consumer favorite, a cod net yields many other white flaky fish that are just as tasty and as healthy as cod. Seaver described his collaboration with hospitals, in which he asked that they include some of these other white flaky fish on their menus to nudge consumers into broadening their diets. As a result, participating hospitals have reduced their food costs and driven more purchasing dollars into their local economies while providing healthy foods for their consumers.

Like Seaver, rather than putting the burden on the consumer to make changes, Parke Wilde from Tufts University considered other ways to guide consumer decision making. He considered several different types of economic incentives aimed at increasing the healthfulness of consumer choice, such as taxing less-healthful products, and discussed how those incentives compare to incentives aimed at reducing the environmental impacts of consumer choice. In addition to economic incentives, Wilde encouraged workshop participants to consider removing counterproductive agricultural and food policies and developing new public policies that more directly address some of the problems at hand.

Key Themes of This Chaptera

• Although overall food prices in the United States have remained steady and will likely remain steady into the future, some food groups show more price volatility than others. Healthier food groups (e.g., fresh fruits and vegetables) tend to exhibit more price volatility than less-healthy packaged foods. (Volpe)

• Consumers can be nudged into broadening their diets in ways that benefit health, environment, and economic issues, for example, through creative menuing (e.g., including “other” flaky white fish that are caught in cod nets that are as tasty and healthful as cod). (Seaver)

• There are several different economic incentives and policy approaches to consider as ways to encourage healthful and environmentally conscious consumer food and diet choices. (Wilde)

_________________

a Key themes identified during discussions, presenter(s) attributed to statement indicated by parenthesis “( ).”

PROJECTED FOOD PRICES: THE IMPACT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSTRAINTS1

A major function of the ERS, the principal economic arm of USDA, is to forecast retail food prices for major food categories. Volpe explained that the forecasts are updated on the 25th day of each month, with the Consumer Price Index (CPI)2 serving as a basis for the forecasts, which extend 6-18 months in the future. The forecasts are based on farm and wholesale price projections, fuel and energy prices, labor wages, and structural breaks (points in time where, for various reasons, the direction of food prices suddenly changes), but not climate change or other environmental changes related to weather volatility. Although ERS researchers recognize these factors, the time frame for the food price forecasts is too short to incorporate them. Because these factors cannot be incorporated into the forecasts, they are the single greatest source of uncertainty, with almost all incorrect forecasts due to unexpected extreme weather events. Recent examples are the unusually warm, wet weather in California and western Mexico in 2010-2011, which led to some surprising and strange phenomena with produce crops; the excessive rainfall in South America in 2011-2012 and its impacts on grain and oil seed prices, especially soybean; and the historic Midwest U.S. drought in 2012. Volpe has observed a rise in extreme weather events, even in his 3 short years at ERS.

Volpe highlighted two important long-term economic trends that have reversed in recent years. The first is an increase in the price of commodities since 2002, both globally and in the United States, after many years of the real price of commodities decreasing (which means that, globally, food was becoming cheaper). The second is a slight increase in the share of disposable income spent on food by U.S. households, after having gradually decreased for many years. In Volpe’s opinion, one likely explanation for the reversals in both of these long-term trends is increased weather volatility, with increased frequencies of extreme weather events driving up commodity prices and making food more expensive. Another likely contributing factor is that U.S. wages have been stagnant for some time.

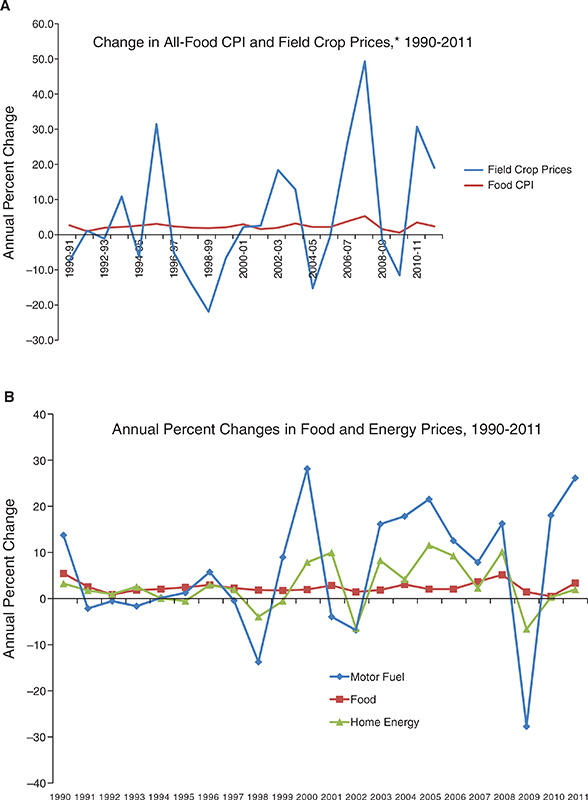

Despite the fact that commodity prices, as well as energy prices, have been on the rise and are growing more volatile, food prices in the United States have remained remarkably stable (see Figure 4-1). Prices for what the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics defines as “personal services”3 have also remained stable over time, as they are typically distinct from fuel and

_________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Richard Volpe, Ph.D., Economic Research Service, Washington, DC.

2 See http://www.bls.gov/cpi (accessed December 11, 2013).

3 In the CPI, the U.S. Bureau of Labor statistics describes “other goods and services” as including haircuts and other personal services (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2013).

energy prices, and the food CPI bears a closer resemblance to the personal services CPI in terms of volatility. The retail food dollar reflects all of the various industries that contributed to putting that single dollar of food on supermarket shelves, with the farm and agribusiness industry contributing 11.6 percent (commodity prices are reflected in that share), food services 33.7 percent, food processing 18.6 percent, retail trade 13.6 percent, energy and transportation 10.3 percent, finance and insurance 4.4 percent, packaging 4 percent, and advertising, legal, and accounting 3.8 percent (Canning, 2011). Volpe explained that the industry shares are parceled out such that even when energy, transportation, and other costs are associated with the farm and agribusiness sector, they are not included in the farm and agribusiness sector share but rather in their respective energy, transportation, or other sector shares. In what is known as a marketing bill, where the farm share does include those other components, the farm share (and thus the commodity price contribution) is never much larger than about 16 percent. Likewise, when the retail food dollar includes only food at home and not food away from home—again, the farm and agribusiness share is never much larger than about 15-17 percent (Canning, 2011).

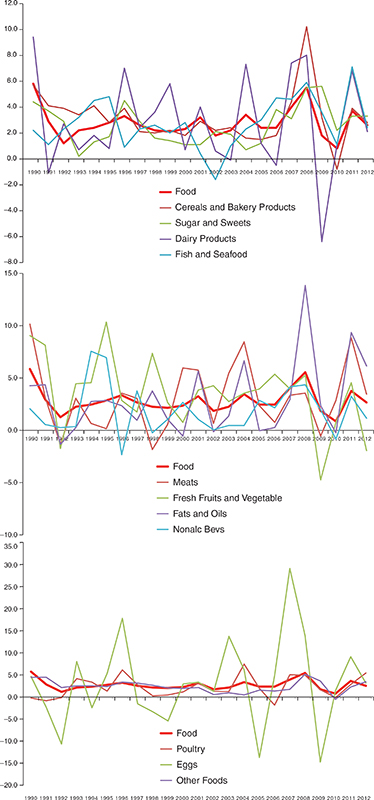

Although, on average, food prices have remained stable, with fluctuating commodity prices having little impact, prices for individual food groups have been volatile (see Figure 4-2). Dairy prices have been especially volatile. Fat and oil prices have also been volatile, largely because soybean prices, which comprise a large portion of that food category, have been affected by weather and export events. Fresh fruit and vegetable prices have also been volatile in recent years, again largely due to weather events. Eggs have been by far the most volatile food category in terms of price. By contrast, one of the most stable food categories in terms of price is what the CPI calls “other foods.” “Other foods” is the largest major food category and includes processed, packaged, shelf-stable foods, for example, a lot of soups, condiments, and packaged side dishes (e.g., boxes of dried mashed potatoes). Factors contributing to the stability of “other foods” prices include advertising and long-term contracts with big-name manufacturers. In sum, according to Volpe, prices for processed, packaged, shelf-stable foods tend to be more stable than prices for most of the food groups that are considered healthy.

What can be expected for the future? According to Volpe, “We are looking at no significant reduction in food supply and very modest increases in overall food price inflation.” The global stocks-to-use ratio4 is expected to increase slightly in 2013-2014, slowing food price inflation (USDA, 2013b). Even though retail food price inflation is expected to continue to outpace inflation of the overall economy, food prices will still remain rela-

_________________

4 Stocks-to-use ratio is a measure of supply and demand interrelationships of commodities.

tively stable through 2022, with an average of 2.4 percent inflation. With respect to climate change, ERS projections for U.S. agricultural production through 2030, based on a range of climate change scenarios, suggest that the impact will be modest even in the harshest scenario, because the U.S. agricultural and food production system has the capacity to respond through geographic shifts (e.g., shifting production away from the West coast) (Malcolm et al., 2012).

THE EFFECT OF NATURAL RESOURCE SCARCITY ON COMMODITY SOURCING5

Seaver began his presentation by saying, “I am thrilled by the conversations that I am hearing … linking environmental sustainability with human health, because I think ultimately they are one and the same.” He said he considered “sustainability” to be “somewhat of a limited term” because, for many people, sustainability is based on the assumption that the best that can be done is to sustain the status quo. Thus, sustainability is inherently subject to a cultural or historical baseline. Seaver suggested broadening the discussion to one that revolves around better use, as opposed to sustained use, of products and encouraged workshop participants to think about sustainability as minimizing environmental impacts of products while simultaneously maximizing the impacts of those products on humans. He encouraged workshop participants to consider the notion of sustainable use: look at the resources being used and consider better ways to use those resources.

Recycling, Organics, and Free Trade: Unintended Consequences

Dissociating solutions to environmental problems from their larger context can lead to a cascade of unintended consequences, in Seaver’s opinion. He cited three examples: recycling, organics, and fair trade. Recycling is largely considered to be the most successful environmental campaign of all time—the refrain “reduce, reuse, recycle” has now been legislated into municipalities nationwide and globally. Yet, there has also been increased pace and amount of recyclable goods flowing into the economy. “Reduce, reuse, recycle forgot the first ‘R,’” he said, “which was to refuse.” If a product cannot be refused, only then should it be used before it can be reduced, reused, and recycled. As another example, Seaver showed an image of American Spirit cigarettes, labeled “Made with 100% organic tobacco.”

_________________

5 This section summarizes information presented by Barton Seaver, chef, and Director of the Healthy and Sustainable Food Program, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts.

The campaign for organic products has led to the creation of what Seaver described as a “fabulous system.” But it has also led to the creation of an unhealthy product, cigarettes, made with organic tobacco. Likewise, he said, fair trade is a “brilliant thing.” Yet, there are reports coming out of Bolivia and Peru indicating that local populations have sold their entire crops into the global market, mostly to the United States, thus sparking fears of hunger and malnourishment among people who have been subsisting on those crops (i.e., quinoa) for thousands of years. Seaver said, “That is great that they are getting a good price, but it is also exacerbating some other issues.”

Seaver emphasized that he does not think there is anything wrong with recycling, organics, or fair trade. He did not use those examples to point out flaws in the systems, which he considered resilient and robust. Rather, the flaw is in what those systems are used for. In his opinion, organic cigarettes are a real abuse of a good system. He said, “We get so caught up in the action that we do not look to the actual consequences.”

Better Use of Products

There is no better example of an opportunity to improve the use of products, in Seaver’s opinion, than the Peruvian anchoveta fishery. Seaver described this fishery as the world’s largest single-species fishery, accounting for 10 to 15 percent of global catch annually. The fishery boats are so big, carrying 60,000 tons of fish at a time, that they cannot get near shore. Instead, the fish are pumped through pipelines to a facility on shore where most are ground and cooked into fishmeal. About 98 percent of the product never feeds a human being directly. It is used in salmon, pig, and chicken farming and in cosmetics, moisturizers, and other products. Seaver visited a plant that processed 14,000 tons per day and employed 28 people, 12 of whom were security guards. Down the street was a canning facility that processed just 2 tons per day but employed 150 people. “This is what we need to be looking at,” Seaver said, “smarter and better usage of the products that we have.”

Seaver encouraged a reexamination of fisheries systems. U.S. consumers eat the same 10 species of seafood, more or less. Of the 16 pounds eaten per person every year on average, 8 to 9 pounds is only 3 species: canned tuna, salmon, and shrimp (NOAA, 2013a). This lack of variety is despite hundreds of federally managed fisheries in the United States that import more than 1,700 different species (Warner et al., 2013).

Eating tuna and other large charismatic fish species is environmentally costly. Seaver compared the trophic scale to a diving board. Jumping at the end of the

diving board creates a large splash. Jumping at the base creates no splash. He said, “Fisheries are just hammering away at the end of the diving board. We need to jump a little bit further toward the middle. We need to be eating more clams, mussels, oysters, herring, sardines, mackerel, and anchovy—these things that are biologically meant to be eaten.… We need to take advantage of some of these natural resiliencies.” Seaver described the “swirling balls of [these lower trophic level] fish in the ocean” and how they breed with such fecundity that they carry on even as they are being eaten.

Many U.S. fisheries have built what Seaver described as “irrational economies.” He pointed to the Reedville, Virginia, seafood landings in 2008 as an example. The Reedville fishery produced 414 million pounds worth $36 million (NOAA, 2011). “That does not end up in a lot of jobs, a lot of houses, a lot of development, a lot of security,” he said. The same is true for other landings across North America. Added to these irrational economies being built up around many U.S. fisheries is the problem of bycatch. In the United States, up to 6 pounds of seafood is discarded for every 1 pound of shrimp caught (Seafood Watch, no date). Globally, almost 40 million tons of seafood are discarded annually (WWF, no date). Some of the discarded fish obviously cannot be eaten, like the puffer fish, but many species could make for a “fine dinner,” in Seavers opinion. He mentioned guitarfish, croakers, drum, and menhaden. “Come over to my house,” he said, “and I will convince you that each of those things is the most delicious thing you have ever had.”

Having made cod “king” in New England is a great example of the irrational demands the U.S. fisheries system has created and the way those demands strain fisheries. A cod net yields not just cod, but also pollock, haddock, tusk, ling, wolf, dogfish, monk, skate, ray, eel, shark, and all sorts of what Seaver described as “tasty flaky white flesh fish.” In the best-case scenario, pollock earns $2.00 at the dock, and dogfish only 10 cents, while cod, being king, commands $6.00. Yet, all of these fish are equally profitable to the human body, in Seaver’s opinion. He asked, “Why are we not setting up a system that is equally profitable to the fisherman?” Why do consumers, when they walk into a store, ask for cod? Why not ask for the best flaky white fish that fits their budgets? By asking for flaky white fish, not cod, consumers would be allowing the ecosystem to provide based on supply, not demand.

Seaver suggested the use of “consumer nudges” to increase sustainable use. He has been involved with some supply-based work with Boston hospitals that wanted to include seafood on their menus more often but were having a difficult time because of expense. The hospitals also wanted to purchase from local fisheries. With Seaver’s help, the hospitals are now menuing seafood four times per week and have reduced their menuing of red meat by two times per week. They are also selling more vegetables because seafood tends to be part of a composed plate that includes veg-

etables. By increasing the menuing of local seafood, the hospitals have not only reduced their costs and driven their purchasing dollars into their local economies, but they have also increased the indexes of healthfulness in their products.

In addition to helping the hospitals menu a diversity of fish instead of simply cod, Seaver has helped them to divert their organic waste into compost. Composting organic waste reduces the frequency of waste pick-up, allows for the hiring of people in the community, and generally redirects otherwise misallocated resources back into procuring sustainable and local seafood.

All too often, in Seaver’s opinion, sustainability is viewed as a separate entity, with advocates standing on their pedestals and saying “listen to me.” The National Geographic Seafood Decision Guide6 takes a different stance. Rather than providing an answer, it provides information that consumers can use to make their own decisions about what they put inside their bodies.

CAN ECONOMIC INCENTIVES DRIVE ENVIRONMENTAL SUSTAINABILITY AND HEALTHIER DIETS?7

Rather than putting the burden on the consumer to make changes, Wilde underscored the importance of thinking about how resource scarcity and the environmental consequences of production affect food prices and how consumers respond to those prices. Wilde drew on the substantial literature on how economic incentives affect the healthfulness of people’s choices, both among the general population and among low-income Americans. He discussed those incentives, compared them to economic incentives for environmental choices, and considered how economic incentives for health and the environment interact.

Incentives for Healthy Choices

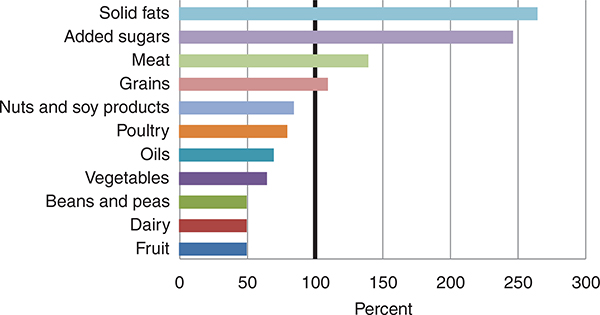

The recommended diet, based on the U.S. federal government’s ChooseMyPlate.gov guidance, contains a high fraction of plant foods, such as fruits, vegetables, and grains. A comparison with current consumption reveals that U.S. adults consume less than the recommended amounts of fruit, dairy, beans and peas, and vegetables, and more than the recommended amounts of solid fats, added sugars, and meat (see Figure 4-3).

_________________

6 See http://ocean.nationalgeographic.com/ocean/take-action/seafood-decision-guide (accessed December 11, 2013)

7 This section summarizes information presented by Parke E. Wilde, Ph.D., Tufts University, Medford, Massachusetts.

FIGURE 4-3 Eating pattern comparisons: Usual U.S. intake for adults (adjusted to a 2,000-calorie level) as a percentage of the corresponding recommendation in the ChooseMyPlate.gov recommended amounts.

SOURCE: USDA/HHS, 2010.

Wilde considered whether taxing less-healthful products or incentivizing in other ways would increase consumption of more healthful products.

Economists use elasticity to measure consumer response to taxes. “Own-price elasticity” is the percentage change in the quantity of a good purchased (“good A”) in response to a 1 percent change in the price of good A. “Cross-price elasticity” is the percentage change in the quantity of good A in response to a 1 percent change in the price of good B. Whether a big versus small elasticity is good depends on the situation. If something with a large elasticity is taxed, then people will reduce their consumption of the good as it is being taxed. So, if the goal is to use a tax on good A to reduce consumption of good A (e.g., cigarettes), then a large (negative) elasticity is good. But if the goal is to use a tax on good A to generate tax revenue, then a small (negative) elasticity is good.

Elasticity estimates are available through ERS and in the public health literature. Andreyeva et al. (2010) reported the following average elasticity estimates: 0.81 for food away from home, 0.79 for soft drinks, 0.76 for juice, 0.75 for beef, 0.72 for pork, and 0.70 for fruit. Beef’s elasticity estimate of 0.75 means that if the price of beef is raised by 10 percent, consumption will fall by 7.5 percent. Although a 7.5 percent decrease is not considered highly responsive, it nonetheless represents a substantial consumer response.

The soft drink estimate is interesting, in Wilde’s opinion, because of the literature around price incentives and snack foods. Although the average

elasticity is 0.79, estimates range from 0.33 to 1.24. An elasticity of 1.24 means that if the price of soft drinks is raised by 10 percent, consumption could fall by 12 percent. One of the counter-arguments to using a tax on soft drinks is concern about what people would consume instead. Based on elasticities estimated by Smith et al. (2010), raising the price of caloric sweetened beverages would reduce consumption of such beverages by 1.2-1.3 percent and increase consumption of juices, but only by 0.56 percent, thus only partly offsetting the nutritional gain from reducing consumption of caloric sweetened beverages. Regardless, Wilde expressed skepticism as to whether taxing less-healthful products would actually work in the United States given the unpopularity of proposals to tax less-healthful products.

Aside from taxing less-healthful products, another way to increase healthful food consumption would be to lower market prices of healthful products. However, Wilde cautioned that it is just as important to think about supply response as consumer demand when considering lowering market prices. Lowering market prices of healthful foods signals to farmers that they should be producing fewer fruits and vegetables. A third option would be to have the federal government subsidize the price of comparatively healthful products such as fruits and vegetables. But those would be expensive subsidies, Wilde said. Finally, rather than creating economic incentives, another option would be to create the political space needed to end counterproductive agricultural and food policies.

The challenge of economic incentives for healthy food choices is different for the low-income population. Although food prices cannot be increased to a point where people go hungry, that does not necessarily mean that no food prices can be increased. Wilde explained that suppressing the prices of all goods reduces the ability of prices to send to consumers highly useful signals about what is scarce and help the economy to run in an environmentally sustainable way. When thinking about low-income populations, factors to keep in mind include elasticities (i.e., people with lower incomes may be more price-responsive); concern about hunger and food insecurity (i.e., prices cannot be increased to a point where people go hungry); and the role of nutrition assistance programs. A number of actions are being taken to affect economic incentives for low-income Americans, including the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) voucher for fruit and vegetable consumption; the New York City proposed restrictions on Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) use for sugar sweetened beverages (which was not approved); and the Healthy Incentives Pilot (HIP) for SNAP (discounts on fruits and vegetables). Wilde noted that some early evaluation results for HIP are available (USDA, 2013a).

Incentives for Environmental Choices

Given that there are economic incentives to encourage healthful food choices, might similar incentives be implemented to encourage environmental food choices? Wilde observed several distinctive features of environmental incentives. First, the food groups incentivized for environmental reasons may be different than those incentivized for health reasons. Second, price incentives for producers are more central to the discussion of environmental issues compared to the discussion of health incentives. Third, the issues are different because it is physically possible to continually consume unhealthy food and beverages, because there is no feedback loop. The opposite is true of foods and beverages that have a negative impact on the environment. Wilde explained that taxing for health purposes in an effort to reduce consumption of a particular food by 10 percent will not necessarily lead to an actual reduction of 10 percent. Although consumption will fall by some amount, depending on consumer response, there is no guarantee that it will fall by as much as 10 percent. The best that can be done is to forecast the 10 percent and tax appropriately. By contrast, if the issue is environmental, for example, fisheries scarcity, then if the availability of fish falls by 10 percent, market prices will rise by some amount, and purchases will actually fall by a predictable 10 percent. Consumer response is predictable in the latter situation, Wilde explained, because demand cannot be greater than supply.

Scarcity is just one environmental issue, one that comes up when discussing fisheries. Another is externalities, which arise when food production has consequences that are not paid by the food producer. An example is water pollution from animal agricultural production or from excessive nutrients in runoff from grain and soybean production. Incentives for consumers to change the environmental impacts of their food choices are different when the environmental impact is water pollution versus scarcity. With scarcity, the adjustment happens almost automatically: food prices increase when a resource becomes scarcer. The same is not necessarily true of externalities. A third environmental issue of concern is what Wilde referred to as “information failures.” Food safety is an example. When consumers do not know the safety of chemicals used in food production, yet a different set of incentives come into play.

Interactions Between Economic Incentives for Health and the Environment

In Wilde’s opinion, when considering the environmental impact of food choices, calories and protein are key. They are the “big environmental sustainability issues,” he said. He noted the substantial discussion of meat at the workshop and its associated externalities. Rather than telling people

to eat less meat, Wilde suggested developing public policy that addresses some of those externalities. The fact that meat is overconsumed relative to U.S. dietary recommendations (see Figure 4-3) means that there is “elbow room” to tolerate price increases, and there would be no need to worry about whether people were getting enough protein if prices were raised. Rather than taxing meat in an effort to encourage people to eat less of it, Wilde opined that “we are on much stronger ground” by solving environmental externalities directly and reassuring people that a price increase could be tolerated.

In addition, Wilde encouraged removing what he described as “counterproductive” policies. For example, the U.S. government encourages consumption of particular foods through the checkoff program policy mechanism, whereby the government lends to a producer board the power to use the federal government’s power of taxation to tax producers to support advertisements such as “Beef: It’s What’s for Dinner” and “Pork: The Other White Meat.” The goal of checkoff programs is to expand demand. Wilde suggested that now is a good time to reconsider the federal government’s role in promotions aimed at increasing meat demand.

Finally, Wilde emphasized the importance of thinking about nutritional assistance programs as a useful part of the toolkit for setting environmentally sound food prices. If there are sound environmental reasons to want higher prices for a particular food group, nutrition assistance programs can help offset the resulting hardship, up to a point. A balance must be reached between sending strong price signals to help the environment and suppressing price signals to protect the poor.

PANEL DISCUSSION WITH THE AUDIENCE

The presentations on price environment raised several questions about the synergies and trade-offs between health and the environmental for some fruits and vegetables; whether the slightly rising food prices should be of concern, given the stagnancy of U.S. wages; the push in the United States to permit large-scale offshore aquaculture in the Gulf of Mexico; the relationship between food prices and obesity; and the food and agricultural industry response to concerns about future climate change.

Fruits and Vegetables: Trade-Offs Between Health and the Environment

Not all foods that are good for people are good for the environment, an audience member observed. For example, the carbon footprint for some fruits and vegetables is higher than for starches and sugars. She asked the panelists to consider the challenges of such trade-offs. Wilde replied that he is “more optimistic” and that he views fruit and vegetable production

as a “comparatively resource-efficient” way to obtain food. For fruits and vegetables without much caloric content, like celery, then, yes, considering how many resources are being used to produce 100 calories of celery, celery production does not seem environmentally sound. But no one eats celery for the calories. Many vegetables, like kale and dark leafy greens, are delivery vehicles for micronutrients, not calories. The fruits and vegetables consumed most frequently, including potatoes, tomatoes, apples, and bananas, have less environmental impact per unit of food produced, especially when compared to meat and other animal products.

Seaver observed that much of the environmental impact of fruit and vegetable production comes from transportation. He suggested freezing foods as a way to minimize greenhouse gas emissions. Richard Volpe agreed that transportation is a major concern and observed the rise in local and regional food systems across the United States.

Seaver also noted an important distinction between having an impact and having too much of an impact. Food production will always have an impact, and common foods like celery will always be part of the expected diet. Rather than demonizing carbon in its entirety, he encouraged finding ways to lessen the impact.

Rising Food Prices, Stagnant Wages

A participant commented on the slow but significant rise in food prices, especially given the stagnancy of U.S. wages. The participant asked the panelists to address this “slow but significant squeeze” and the fact that the food industry is among the lowest-wage-paying sectors. Volpe agreed that median wages across the economy have been fairly stagnant for a long time, while retail food prices have been increasing at about 2.5 to 3 percent annually during the last 20 years or so. That said, the rate of inflation for food prices has actually been slower than the rate of inflation overall. Only since around 2006-2007 has that trend shifted and a squeeze been observed (i.e., a greater proportion of income being spent on food). If the proportion of income spent on food continues to increase in the future, then there will be some real concerns.

With respect to the food industry being among the lowest-wage-paying sectors, Volpe agreed that, at the farm level, there is increasing concern that the farm share of the U.S. dollar is decreasing. However, there are policies in place to provide a safety net for U.S. food supply producers. In his opinion, the fact that the recent Midwest drought did not hit farm incomes as much as originally forecasted demonstrates the success of those policies.

Another participant asked whether panelists had any policy recommendations for making food more affordable for people who cannot afford it. Wilde pointed out the role of nutrition assistance programs. SNAP includes

an automatic inflation updater, with benefits being increased in proportion to the previous year’s inflation-adjusted price estimates. But he also encouraged food system advocates to think beyond nutrition assistance programs. He mentioned the 1990s bipartisan agenda for economic improvement and anti-poverty progress. Although one side of the aisle emphasized moving people into the workforce and the other side emphasized anti-poverty programs, there was a sense from both sides that Americans ought to be making economic progress. He said, “I hear [an emphasis on poverty reduction] from few people in recent years that have any political influence.” Moderator Deborah Atwood, executive director of AGree, noted that, according to recent findings, about one in four people eligible for SNAP does not participate in the program and wondered about the implications of this lack of participation for the need to find bipartisan answers (Food Research and Action Center, 2013).

Volpe added that the WIC program is another very large food assistance program in the United States that provides purchasing power to low-income Americans to buy healthy foods (e.g., infant formula, milk, bread, cereal). WIC is not an entitlement-based program. Funding comes entirely from annual appropriations from Congress. The extent to which women, infants, and children are able to be served by the program depends on cost-efficiencies of the program. In Volpe’s opinion, it is becoming increasingly clear that WIC faces a structural problem in terms of cost containment. However, he has observed much more concerted focus in the last couple of years to maintain or even increase overall participation capabilities of the program.

Aquaculture Versus Wild Fisheries

An audience member representing the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future asked Seaver about the push in the United States to permit large-scale offshore aquaculture in the Gulf of Mexico. Seaver replied that aquaculture accounts for about 50 percent of global consumption of seafood (NOAA, 2013b). The United States is the third largest consumer of aquaculture products, yet produces only about 1 percent of the global total (FAO, 2012)—a discrepancy that Seaver described as a “total failure.” He said, “We really should be farming more fish.” Aquaculture has received a “bad rap,” but rightly so, in his opinion. However, it is a very young, very dynamic, and well-capitalized industry. Technological advances are occurring rapidly, even within the lowest grades of aquaculture, and Seaver predicts that many of the environmental problems that have been associated with common aquaculture practices will disappear within the next 3 to 5 years. For example, farmers are using selective breeding to develop strains of salmon and other fish that are inherently more sustainable. These

salmon are able to create long-chain fatty acids out of plant-based products, diminishing the need to use fish meal in their feed and thus reducing their negative impact.

Moreover, in Seaver’s opinion, some aquaculture products, like cultured oysters, are more than sustainable. They are restorative. Planting oyster beds not only helps to replenish native oyster populations, but also performs a vital ecosystem service. Oysters feed on the algae blooms that result from the excessive nutrients being discharged into the ocean; by allowing sunlight to penetrate further through the photic zone, they also create substrate and habitat for other species, thereby increasing total biomass and biodiversity of the marine ecosystem.

Seaver views aquaculture as a way to create new products, not replace old products. Moreover, an aquaculture program that complements the U.S. wild fisheries program would not only create new products, it also would create new jobs. He pointed out that more of America is underwater than above water and that the U.S. economic zone is much larger than its terrestrial territory. In his opinion, it is time to take greater advantage of that underwater economic zone.

Food Prices and Obesity

Based on the trends reported by Volpe, an audience member observed an apparent correlation between falling food prices and rising obesity rates. A recent study in the British Medical Journal described a coupling between food and fuel shortages in Cuba in the 1990s and a subsequent decrease in obesity and type 2 diabetes rates among Cubans; after food prices stabilized, the obesity and type 2 diabetes rates rebounded (Franco et al., 2013). The audience member asked the panelists to comment on the relationship between food price and health. Volpe mentioned a long history of data dating back to medieval times showing an indirect relationship between the price of food and health problems related to obesity and overweight. However, he does not view food prices in the United States as a major driver of obesity or diabetes. He views the growing number of nontraditional store formats (e.g., food marketing in super centers and in dollar stores) as the more important driver. In his opinion, where consumers shop matters. Whether a consumer purchases his or her food at a super center, club store, dollar store, convenience store, or elsewhere has health implications. Volpe expressed concern that the issue is being oversimplified as a food price-health relationship. Food at these nontraditional stores tends to be cheaper, whether measured on a per-serving or per-calorie basis. The more relevant issues, in his opinion, are food availability, product menu, private label ingredient (or store-developed ingredients/products), and other ways

that nontraditional store formats are evolving to meet and shape consumer demand.

Seaver clarified that the 1990s period of food scarcity in Cuba was a “nasty chapter” in the history of Cuba, not a celebration of the reduction of disease. Moreover, he warned that obesity is too often construed as a symptom of food. In his opinion, it is not. It is a social construct. Health itself is a social construct. He views obesity as the product of a system that is not set up to sustain humans. He noted the way houses are built around televisions, cities are eviscerated by freeways, and people lack access to parks. Although food is certainly a vehicle to obesity, obesity is also part of a much broader societal construct of quality of life.

Wilde emphasized the importance of recognizing the wide variety of plausible explanations for obesity and said that the decline in cost of food per person, relative to income, is a sign of prosperity. Prosperity is, in his opinion, a “good thing.”

Climate Change and Agribusiness

An audience member asked Volpe if there is any evidence that agribusiness is responding to the climate change patterns being observed in the United States (e.g., shifts in precipitation, temperatures, growing season patterns). Volpe responded that he has not observed any clear trends. He expects that the initial response will be at the production stage, in farming, and that the response will then filter down through wholesale and so on. But he suggested that other experts within the ERS would probably be better suited to answering the question.

Another member of the audience added that PepsiCo and other companies have been working with agricultural economists and climatologists to predict the likely future consequences of climate change. They are taking very seriously the likelihood that some crops will be in the middle of a desert, while others will be in the middle of a flood zone, and they are planning commodity changes based on those likely scenarios. Also, the World Economic Forum, a grouping of major agricultural and food companies, has been examining this same issue and making plans that extend 50 years into the future, not just about respect to what to plant but also about how to plant. The audience member suggested that the sense of “urgency and awareness” is greater in industry than in government.

Andreyeva, T., M. W. Long, and K. D. Brownell. 2010. The impact of food prices on consumption: A systematic review of research on the price elasticity of demand for food. American Journal of Public Health 100(2):216-222.

Canning, P. 2011. A revised and expanded food dollar series. ERR-114. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

ERS (Economic Research Service). 2012. Food prices less volatile than fuel prices. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/charts-of-note.aspx (accessed October 18, 2013).

ERS. 2013. Food price outlook. Charts. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-price-outlook/charts.aspx#.UmF-9nDkuSo (accessed October 18, 2013).

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). 2012. State of the world fisheries and aquaculture, 2012. Rome: FAO.

Food Research and Action Center. 2013. SNAP/food stamp participation. http://frac.org/reports-and-resources/snapfood-stamp-monthly-participation-data (accessed September 6, 2013).

Franco, M., U. Bilal, P. Orduñez, M. Benet, A. Alain Morejón, B. Caballero, J. F. Kennelly, and R. S. Cooper. 2013. Population-wide weight loss and regain in relation to diabetes burden and cardiovascular mortality in Cuba 1980-2010: Repeated cross sectional surveys and ecological comparison of secular trends. British Medical Journal 346:f1515.

Malcolm, S., E. Marshall, M. Aillery, P. Heisey, M. Livingston, and K. Day-Rubenstein. 2012. Agricultural adaptation to a changing climate: Economic and environmental implications vary by U.S. region. ERR-136. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2011. Fisheries of the United States, 2011. http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/stories/2012/09/docs/fus_2011_fact_sheet_final92012.pdf (accessed September 9, 2013).

NOAA. 2013a. Seafood and human health. http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/aquaculture/faqs/faq_seafood_health.html#6how (accessed September 9, 2013).

NOAA. 2013b. What is aquaculture? http://www.fishwatch.gov/farmed_seafood/what_is_aquaculture.htm (accessed October 7, 2013).

Seafood Watch. No date. Wild seafood issue: Bycatch. http://www.montereybayaquarium.org/cr/cr_seafoodwatch/issues/wildseafood_bycatch.aspx (accessed October 29, 2013).

Smith, T. A., B.-H. Lin, and J.-Y. Lee. 2010. Taxing caloric sweetened beverages: Potential effects on beverage consumption, calorie intake, and obesity. ERR-100. Washington, DC: U.S Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2013. Frequently asked questions (FAQs). http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpifaq.htm (accessed October 10, 2013).

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture). 2013a. Healthy incentives pilot (HIP). Interim report. http://www.fns.usda.gov/ORA/menu/Published/SNAP/FILES/ProgramDesign/HIP_Interim.pdf (accessed October 18, 2013).

USDA. 2013b. USDA agriculture outlook forum. Grains and seeds outlook. http://www.usda.gov/oce/forum/presentations/GrainsOilseedsOutlook.pdf (October 18, 2013).

USDA/HHS (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). 2010. Dietary guidelines for Americans. 7th Edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Warner, K., W. Timme, B. Lowell, and M. Hirshfield. 2013. Oceana study reveals seafood fraud nationwide. http://oceana.org/sites/default/files/reports/National_Seafood_Fraud_Testing_Results_FINAL.pdf (accessed October 7, 2013).

WWF (World Wildlife Fund). No date. Fact sheet: Bycatch. http://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/bycatch_factsheet.pdf (accessed October 7, 2013).