A Case History of Organizational Change: People and New Technology

JAMES R. HETTENHAUS

International Bio-Synthetics (IBIS, Inc.) is a shareholder-originated joint venture between the Shell Group and Royal Gist-brocades to commercialize the results of research and development. Formed in 1987, IBIS produces fine organic chemicals, biopolymers, pharmaceutical intermediates, and enzymes. This case study describes the process by which IBIS increased its productivity by more than 30 percent and reduced its costs of operation through organizational change and the concurrent introduction of centralized process control technology.

The company has three manufacturing locations—Kingstree, South Carolina; Halebank, United Kingdom; and Brugges, Belgium. Products in Kingstree are primarily industrial enzymes used by the starch, detergent, and textile industries. The Kingstree plant was built in 1960 and expanded in 1962 and 1966. Extensive modifications to plant processes were made in 1978, and expansion occurred in 1983.

Manufacturing operations are mostly large-scale fermentation. Fermentors include batch, fed batch, and solid substrate types of varying size, exceeding 100 cubic meters. Recovery of products is by aqueous or solvent processing. Unit operations include filtration, evaporation, ultrafiltration, drying, and blending.

TRADITIONAL APPROACH

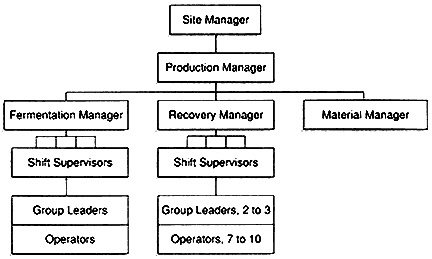

For the first 24 years, the plant was organized by function (Figure 1). Six levels existed between the operator and the president

or managing director. Departments worked independently, relying on the hierarchy to coordinate activities. Shift supervisors were assisted by lead men in various processing areas to direct operator activities. Decision making was necessarily autocratic, since information relating to cost, customer requirements, and technical and administrative facts was available only to management. Other people were not trained to use it. Operator training was limited to specific processes, resulting in little flexibility for assignment. Production tracking was referred to as the "paper mill" and required time and clerical assistance. Production results were often delayed because of detailed documentation of the batch process that occurred as part of production tracking.

Cyclical swings in business resulted in temporary layoffs. The work force reduction was determined by seniority. Performance appraisals were not made for production operators. As new work assignments were made to fill in behind the vacancies, a decline in performance was inevitable. The shift supervisor received the brunt of the blame associated with the disruption and, paradoxically, had more work in directing people in the new assignments.

Overall plant performance was considered satisfactory. Regular investments were made to keep the plant technically current. In 1983, as part of the solvent-recovery process, a distributed process

FIGURE 1 Organization of the Kingstree plant, by function, before 1984.

control system was installed along with programmable logic controllers (PLCs) for operation of new membrane filtration and ultrafiltration equipment. In 1982 Quality Circles were established. About 20 percent of the employees volunteered to work on projects that would improve quality. A facilitator met with five groups, provided some basic training, and completed one cycle—one project per group. The activities were outside of normal work requirements, and participation was limited to less than 20 percent of employees. Training for first-level supervisors was also initiated. A traditional text was used to introduce basic supervisory concepts. As an outgrowth of Quality Circle exposure and supervisory concepts, the first-level supervisors undertook a project to develop an operator performance appraisal system in 1984.

A CONCURRENT APPROACH TO SYSTEM CHANGE

In 1984 a plant evaluation team was formed to determine the potential for improvements. An assessment of both the organizational and technical system capabilities yielded recommendations for moving toward a more participatory work environment. At the same time, enabling technologies were installed to consolidate data for analysis and better disseminate the information. The job redesign that resulted from the assessment employed a sociotechnical approach.

Autonomous self-regulating teams would be formed for material handling, maintenance, laboratory administration, and production, with initial emphasis on production. The organization would be pushed to make effective use of material requirements planning (MRP), manufacturing resource planning (MRP II), decision support systems, and centralized control of the process operations.

In addition, first-level supervisors would move to a supportive resource role, providing direction and support to the team as needed. As supervisory technical resources (STRs), they ensure that the level of operations is maintained and improved congruent with the team concept. Essentially everyone in the plant would have a new and expanded role.

In 1985 plant implementation began when the new site manager, a member of the evaluation team, held a series of plantwide meetings to communicate to all employees the future work environment. He enlisted their participation in developing and implementing the plan to achieve the new environment.

ORGANIZATIONAL RENEWAL

The Quality Circle training and supervisor training, begun in 1984, were good reference points for the plantwide effort in 1985. The Quality Circles provided an introduction to problem-solving skills and interpersonal skills essential for the emerging teams. The basic management knowledge gained by the supervisors helped them begin the transition from direct control of workers to becoming a "resource" with multiple roles.

In 1985 the department shift supervisors were replaced by one plant superintendent who rotated with the shifts to be available as a "resource." This permitted the work groups to evolve into teams while freeing former shift supervisors to carry out their new assignment as team resources. In 1986 the role of plant superintendents was discontinued on the shift, and they also moved to a new, more focused role as team resources.

A New Shift Schedule

The production team rotation was changed to permit five crews to rotate through a five-week schedule. Developed with the assistance of a physiological psychologist, the schedule was designed to accommodate five crews so that training could be accomplished without overtime.

In determining the new schedule, a representative from each shift was selected by the members of that shift. The representative was to participate in evaluating other schedules. Initially, the representatives assumed their role would be simply to rubber stamp a predetermined scenario. The consultant who was directing the effort was quite explicit that there was no predetermined schedule, that it was up to them as representatives to evaluate alternatives, take the evaluation back to their fellow shift members, and discuss the pros and cons. After several iterations, the teams should have an understanding on disagreements and agreements and approach a consensus for the new work schedule. This first experience was an important precursor to getting participation in other activities. During the early stages of implementation it became clear that many of the participants needed to improve interpersonal and meeting skills.

Individual Performance Appraisals

In 1984 pro forma appraisals were given as a trial. Feedback was used to adjust for actual appraisals, to begin in 1985. As

planned, the following year the performance appraisals for all individuals, including operators, were implemented. This permitted a move from work force curtailment by seniority to work force curtailment based on performance. Although layoffs are certainly undesirable and can generally be attributed to poor management, the cyclical nature of the business in 1985 required a temporary work force reduction. Without performance appraisals, some of the most capable operators would have been lost and the new organizational efforts would have been jeopardized.

Process Performance Measurement

In 1985 a personal computer (PC) network was installed to link the laboratory with the production and accounting departments to improve process performance measurement. The lab results, coupled with production information, permitted fast determination of material balances around each unit operation: fermentation, harvest, treatment, filtration, concentration, and blending. The rapid feedback of these results to the operating teams allowed them to measure their performance and make adjustments as required.

Clipboards, manual calculators, and paper shuffling were eliminated. More time was available to analyze and solve problems. By year end, process performance had improved 40 percent from the baseline established in 1984. The improvement was primarily attributed to rapid feedback of results to better trained operators. The operators were using their new autonomy to work smarter. When a variance from production targets was identified, it would be identified earlier, and action would be more rapid and more correct.

In addition, the results of the innovation, or corrective action, were easily communicated over the PC network. The network's common data base included all operating amendments, the reasons for changing the process, and shift logs.

Training

The training program was established using the reassigned shift supervisors as instructors. Two former supervisors attended a special course to provide them the necessary training skills. The new five-week rotation provided four days for training without overtime. Two days were initially used for group training; the other two for individual training. The first training focus was on

job skills—why we do what we do. New mistakes were taken as a learning experience. A pass-or-continue policy was emphasized to reduce the fear of failure and to help people gain some self-improvement. When a mistake in processing occurred, it was termed an "unusual incident." Team meetings were held to analyze the problem. Problem-solving skills were developed simultaneously. Alternatives were evaluated and corrective action taken. In some cases discipline was recommended, especially as the team matured.

The second phase of team training focused on skills and knowledge required for administrative responsibilities. These tasks were previously performed by the supervisor. They included production coordination, safety, maintenance direction, quality, people administration, good manufacturing practice (GMP), and sanitation. The third training phase focused on interpersonal skills: communication, conflict resolution, and group process. As the teams develop, the administrative and interpersonal skills and knowledge are as important as the core job skills and knowledge of the process.

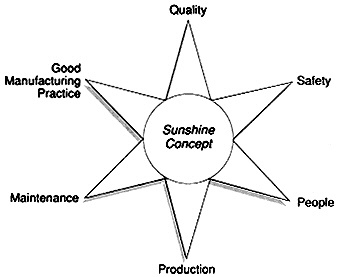

Sunshine Concept

The administrative roles evolved into the Sunshine Concept (Figure 2). This concept was introduced in 1986 when a group composed of managers, STRs, and team members attended a team

FIGURE 2 Sunshine Concept for organization of administrative roles.

leader course offered by Ketchum Associates. Attending one week per month over five months permitted assimilation and emergence of the Kingstree Team Concept. The course has evolved and improved, using feedback from the original attendees, and other internal and external influences. In 1988 a second group completed the improved training.

Responsibilities and tasks for each ray in the Sunshine Concept (as shown in Figure 2) are defined between the ray and the resource persons designated among the STRs. Each team member has two assignments: one as the team "ray" for a designated area; the other is a secondary, or backup, for another area. The dual role ensures that the team is always represented and broadens the individual perspective.

The rays provide the measure of self-regulation needed for team performance. For example, the GMP ray is not responsible for cleaning but ensures that everyone on the team carries out sanitation and GMP as an integral part of the job. The ray serves on the plantwide GMP Steering Committee and meets regularly with GMP rays from other teams along with resources. They track and review overall plant performance and adjust the work plan as required to meet plant objectives and goals.

The people ray especially distinguishes the Sunshine Concept from unsupervised work groups or teams under the direction of a team leader. The people ray carries out routine administrative responsibilities such as coordinating vacation, overtime, training schedules, and time sheets. The people ray also provides the measure of self-regulation of team and individual performance and, with the team's participation, identifies training needs for the team members. The people ray also represents the team in determining the pace of organizational development and overall personnel needs.

The Sunshine Concept requires many meetings to exchange information, plan, critique performance, and adjust activities. Daily meetings are held with other team members. Monthly meetings are held with rays from other teams to review results and adjust work plans for each area: quality, safety, GMP, people, maintenance, and production. In addition, each team ray can meet as needed with STRs and others.

Self-Evaluation

In 1988 the organizational development of the teams continued as teams and resources met for self-evaluation in a series of work

shops off-site. Internal team performance, performance between teams, and the relationship between the resources and teams were evaluated. The workshop also addressed the overall goal toward which IBIS is working. A statement describing this goal was used to draft a specific related, supportive statement pertinent to the team. A series of action points was developed. A reevaluation followed in six months. This continuous self-evaluation establishes an improved level of performance as the team concept matures, achieving more complete self-regulation.

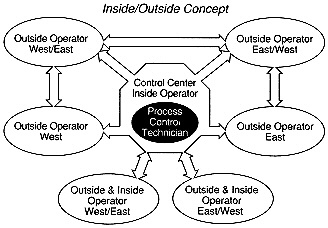

Inside/Outside Concept

For more than 20 years, large petrochemical and refinery installations have operated integrated processes from central control rooms. An inside operator directs activities of field workers. The control center often serves as a meeting place. It may also house the process control lab and meeting rooms.

Although the Kingstree processes are not continuous, the same control philosophy was adapted to the batch and semicontinuous operation. The installation of a centralized process system was planned in 1987. A job skills training program was initiated in 1986 to broaden the knowledge of team members. Each team is composed of both inside and outside operators. Rotation is based on individual capabilities, work requirements, and available time for training and rotation to keep skills current. Figure 3 shows

FIGURE 3 Inside/Outside Concept for the movement of operators between the control center and the east and west plants.

the movement of outside operators between the control center and the east and west plants. Regular rotation of assignments is important to maintain a plant organization, empathy for other positions, and an understanding of both outside and inside work. Just as there are primary and secondary ray roles for each team member, there is a minimum of two per team for each assignment for the Inside/Outside Concept.

The inside operator is designated as the quarterback. The new PC network and Process Control Center allow the quarterback to manage the process by exception, identifying variances. Although quarterbacks set priorities and call the plays, they are not supervisors, but equal team members. Because of the position in the control center, the quarterback has access to the information necessary for overall work coordination of the shift.

The rotation sequence helps ensure that an egalitarian atmosphere prevails. If the team has just two qualified quarterbacks, they rotate between the inside and outside assignment. When a team has more than two qualified operators, the rotation is extended from outside only; outside, relief for inside; and then inside.

The outside operator is not a set of arms and legs but a knowledge worker applying a high level of training to a multitude of situations. Guidelines for the outside operator apportion work times equally among three functions: regular routine; process batch cycle; and breaks, exceptions, and time to think.

The regular routine includes equipment checks in the field according to a schedule established by the resource and production ray members. Outside operators check the water level in cooling towers and the oil temperature of compressors and monitor other field instruments and activities that are not included on the inside operator's console. Process batch cycles result in a varying work load. For each batch there are solutions to prepare, samples to take, and equipment to assemble, dismantle, sterilize, or clean, along with numerous other activities. Although some flexibility exists, work planning is essential to smooth out busy periods when available resources may be exceeded. The outside operator also requires time for breaks and dealing with exceptions. Most important, time is required to plan the work with fellow team members and to think. The control center is designed to be the meeting place so that the team can regularly see each other and interact personally, apart from their routine radio and telephone communications.

Team performance has continued to improve. In 1984 the shift

operators functioned independently, receiving direction from their shift supervisors. In 1985 they began to work as an unsupervised group. In 1988 the group became a largely self-regulating team.

The team's work skills and knowledge have continued to improve. Productivity has improved by more than 30 percent while following the 1/3, 1/3, 1/3 guidelines. The team determines the shift staffing level following the guidelines. Current production teams consist of six members, with some overtime required.

|

|

Production Team Staffing |

||||

|

Year: |

1985 |

1986 |

1987 |

1988 |

1989 |

|

Team size: |

10 |

8 |

7–8 |

6–7 |

6 |

In 1988 a production team quarterback and an STR made a presentation to the Manufacturing Automation Users Council in Phoenix, Arizona (Dennis and Rogers, 1988). In their presentation, both stressed that the system continues to evolve, ensuring continuous improvement of the process.

Learning

Nearly all of the operators' learning was new learning, which extended their understanding of why things occurred the way they do. Most operators welcomed the organizational changes. About 15 percent, however, found it too difficult to accept the responsibility or work without direct supervision and chose to go elsewhere. It was regrettable that approximately half were excellent performers with the old system but were unable to adjust to the changes.

The role transition is perceived as a more difficult adjustment for first-level supervisors, since they need to unlearn the way they have been working for more than 15 or 20 years. Moreover, there was no role model for a ''resource'' in 1984.

Indeed, the concept of autonomous teams met with skepticism when it was presented to the supervisors. They perceived the safest assignment would be as plant superintendent, working with the rotating shifts. At the end of 1986, no shift supervision was required and, in contrast to the expectations of many, progress was accelerated as former first-level supervisors assumed resource roles that evolved into STRs.

To assist the former supervisors in making the paradigm change, new learning was emphasized. A manager of change was named

immediately in January 1985 to ensure that IBIS moved away from bureaucratic procedures toward more innovation. However, too much change could result in confusion, excessive mistakes, and lack of coordination. IBIS recognized the need for procedures and controls and continued with some parts of the hierarchy such that both the teams and the resources could request support as well as give direction. There is also interdependence within levels to promote interpersonal relationships between the functional roles.

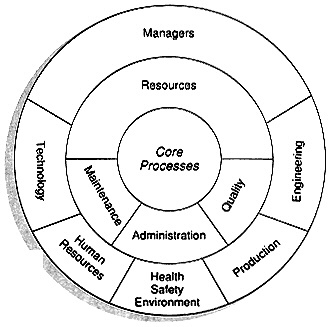

The IBIS organizational structure is redrawn in Figure 4 to represent the team concept. Information and resource sharing, along with mutual support, are emphasized. The teams connect with the core process, supported by resources and managers. However, the boundaries for much of what IBIS does are not as clear as Figure 4 indicates. As skills and knowledge develop, all boundaries shift and become broader.

A third organizational type—an adhocracy—illustrates an organization's readiness to accept boundary adjustments to facilitate innovation and change. The effort goes into implementing change and not dealing with organizational resistance to overcome inertia.

A fourth organizational type recognizes the need for individual

FIGURE 4 Current organization of the Kingstree plant, by teams.

contribution, clear goals, and direction. In contrast to most firms, IBIS perceives each individual as the center of the network, connected with information technology and capable of continuous organization transformation.

Organization always lags what is required today because it was organized to accomplish yesterday's tasks. The shorter the time lag, the more effective the business. To achieve high performance, organizations have continuous self-destruction and reconstruction. IBIS must also master the paradox of dealing with conflicting organizational types: hierarchy and adhocracy, teams and individuals. These concepts are more fully developed by Davis (1987) and Quinn (1988).

If teams are overemphasized, a country club atmosphere can prevail. However, a lack of information sharing by individuals results in duplication of costly learning experiences. It also deprives the team of essential information. On the other hand, individual performance and contribution are important and are recognized by the significant work and administrative responsibilities each team member has as both a ray and a key decision maker in the manufacturing process.

As the role of the supervisory technical resources evolved, they were initially reluctant to intervene, feeling much more comfortable with coordinating, observing, coaching, facilitating, and training. Managing the paradox, between intervention and resumption of what could be perceived as role reversion to the old paradigm, was a delicate balance. IBIS's success is attributed to positive results being achieved as we moved toward self-regulation, which more than offset the unusual incidents. IBIS abided by the basic precept of Lyman Ketchum: "Teams learn self-regulation by self-regulating."

Outside Resources

Most of the outside resources employed for IBIS organizational development and assistance in making the paradigm shift dealt with people rather than technology. Early in 1985 a Dale Carnegie course was offered to everyone in the plant. Eighty percent of the people completed the six weeks of training offered outside of regular work hours. The level of self-confidence of all participants improved, and communication abilities were enhanced. IBIS was off to an excellent start. About 10 percent of the people were also enrolled in the full 12-week course off-site. Concurrently, Rational Problem Solving courses were provided to all employees. About

20 percent of the managers and resources attended Kepner-Tregoe week-long courses off-site.

Recognizing that rapid change contributes to stress, IBIS established a stress-management and wellness program. The physiological psychologist who assisted in the schedule resolution was retained for the first three years. During the psychologist's weeklong visits, generally once every four or five months, small group sessions were scheduled for everyone in the plant. The causes of stress were discussed, along with stress management techniques, exercise, and proper nutrition. Time was made available for individual counseling.

A survey at the end of three years showed that one-third of the plant community made some adjustments as a result of the program. Another third said they made a significant change in their life-styles. The remaining third stated they were better informed but had made no change. All believed the program results were mutually beneficial in accelerating the change process, recognizing that stress was present, and providing the tools to manage it.

Another practice that had to be encouraged was asking for help. In the past, asking questions was often viewed as an inability to comprehend "what everybody else already knows." It was especially awkward when a subordinate questioned a person in authority. Because it is essential for IBIS's success that everyone be comfortable in asking for help, Interaction, a course offered by Development Dimensions, Inc. (DDI), was provided to everyone. An individual was trained off-site by DDI to become a facilitator and six in-house facilitators were selected and trained. Next, plantwide courses were scheduled using a combination of videotapes, exercises, and open discussion over a three-month period. The videotapes and other materials were unusual in the way they avoided reference to the traditional relationship between supervisors and subordinates.

In addition to encouraging people to ask for help, the training reinforced two other principles: having respect for others and having empathy for the person in the other position. The program also helped to establish a common language. The timing was important. The need for this course was well recognized and appreciated as another tool in facilitating the organizational change.

TECHNOLOGY

The 1984 baseline study identified potential advantages of installing a PC network to improve information flow and using manu-

facturing resource planning (MRP II) to reduce working capital requirements and improve equipment use and productivity. The study also recommended a centralized control station for better integration of plant operations. The PC network was installed in 1985 and has been continuously expanded. The MRP II system was selected in 1985, brought up later that year, and fully implemented in 1986. The centralized control was designed in 1986 and implemented in 1987. All plans have met or exceeded expectations (Horton, 1988; Jansen, 1987; Nisenfeld, 1988; Weber and Nisenfeld, 1987).

PC Network

Design and implementation of the PC network was accomplished using computer science students from the local university. An elementary approach allowed rapid results. After several iterations with the users on the plant floor and in the control room, laboratory, and other areas throughout the plant, current operating results were available. The performance measurements facilitated the communication that was essential for cost improvements. More than 50 PCs are now used on applications ranging from simple document retrieval to expert systems that support operator decision making.

MRP II

In 1985 a cross-functional team was charged with selecting generic software to replace the "paper mill" used for production tracking. At the same time, the team was to identify opportunities to redesign the work to enable people to better use the technology. Members included representatives from customer service, order entry, accounting, accounts payable, accounts receivable, purchasing. warehouse, production planning, project engineering, and maintenance. After a cursory screening, two vendors provided software for a week-long evaluation by the potential users. A selection was made, and the next nine months were required for more complete training, configurations, and start-up. The results met or exceeded all objectives. More than 10,000 square feet of warehouse space was opened up by better resource planning. The maintenance stock reduction was greater than the software cost, and a large reduction in raw materials was achieved.

Centralized Control

In 1984 local control areas existed around the plant, along with much field instrumentation. An automation plan was designed for integration by stages to match IBIS's capital budgets and resources, and Combustion Engineering Corporation proposed a shared-risk/shared-benefit venture (Blickley, 1987). After a detailed engineering study of costs and savings, a distributed process control system, MOD 300®, was installed. IBIS and Combustion Engineering share in the benefits in proportion to their investments for five years or until the system is paid off. A former first-level supervisor was given the title manufacturing representative (MR) and assigned to ensure that the project met the production operators' needs. In this new role, the MR was responsible for training of operators, speaking for production, providing information to engineering and others necessary for the design, and communicating project status to everyone in the production organization.

The design of the operator interface display was a cooperative effort between the control engineer and the operators. Tag numbers were used and extensive training was provided. Operators became knowledgeable about every component in the instrument loop: sensor, transmitter, controller, and final control element. They reviewed the algorithm development. Process piping and instrumentation drawings were put on AUTOCAD®, a computer-aided design system, so that revisions could be readily accommodated and always available to anyone. Most important, all operators interpret and troubleshoot malfunctions and variances as they occur. This minimizes start-up problems and maintenance calls.

In mid-1987 the first fermentation controlled from the new system saved $6,000. Since then the remainder of the fermentors and the recovery operations have been consolidated into the control center. Again, all results have met or exceeded expectations.

Systems Integration

Currently the PC network, MRP II, and distributed control system are independent islands of information. An integration project is in process to establish a common platform for the enterprise.

A manager of enabling technologies has been named. This position combines management information systems with process control systems. The information systems team serves as a re-

source to accounting, sales and marketing, finance, manufacturing and engineering, and others.

Combustion Engineering has offered to extend the contract to include many of these additional capabilities under the shared-risk/shared-benefit concept. This commitment of continued vendor support provides IBIS a significant extension of resources to help ensure project success. In addition, organizational flexibility, continuous training, and commitment to continuous improvement ensure that the gains will be realized.

CONCLUSION

In the old paradigm, change is implemented as chapters in a book, with each department or function completing a chapter. There is little interaction and even less iteration through various stages of implementation. The results of this approach are periodically brought into focus when airline pilots and flight controllers threaten to "go by the book." In nearly any location, when one goes strictly by the book, using the old paradigm, effectiveness and productivity suffer. Innovation is restricted if not eliminated.

In the new paradigm, change is implemented using a plan that can also be compared to a book. But the development occurs in a more participatory sense: the outline provided first, and people responsible for the implementation participating in the design, development, start-up, and all other phases. Iterations are expected and promoted. In this way innovation continues to occur, and an atmosphere for continuing change is created.

With the new paradigm, capabilities of many are used on a broader scale. The "big picture" or "helicopter view" is available to everyone. People are permitted, indeed encouraged, to close the gap between what they are doing and what they are capable of doing.

REFERENCES

Davis, S. M. 1987. Future Perfect. New York: Addison-Wesley.

Dennis, R. E., and R. A. Rogers. 1988. Training education and incentive systems sociotechnical design: The plant floor view. The Yankee Conveyor (April):18–21.

Blickley, G. J. 1987. Process control users can be tough customers. Control Engineering (October).

Horton, M. 1988. The Technical, Economic, and Social Issues and the

Results of an Automation Retrofit to a Biotechnical Plant. AIChE Spring Convention, New Orleans, March 7, 1988.

Jansen, R. 1987. An Energy Enhancement Project: One Step on the Road to CIM. Thirteenth Annual Advanced Control Conference, Purdue University, September 28–30.

Nisenfeld, E. 1988. Plant automation: A five-year plan that worked. Control (October):93–102.

Quinn, R. 1988. Beyond Rational Management. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Weber, M. G., and E. Nisenfeld. 1987. Operator Decision Support System as Part of CIM. Thirteenth Annual Advanced Control Conference, Purdue University, September 28–30.