Operations Research in Nurse Scheduling

THOMAS CHOI, HELEN JAMESON, AND MILO L. BREKKE

Among all the problems that currently plague the nation's health profession, perhaps none is so obvious and detrimental as the much publicized nursing shortage. At a time when hospitalization policies mean only the very sick patients are admitted, the retention of nurses, especially qualified nurses, is paramount. Nurses are the largest work force in any hospital and are basic to the operation—but in recent years their turnover rate has been as high as 50 percent (Prescott and Bowen, 1987). An inability to maintain nursing manpower can radically affect quality of care. Clearly it is imperative that ways be found to increase job satisfaction, and thus retention, for qualified nurses.

What makes nurses resign? Previous studies have shown that discrepancies or disappointments between what nurses expect of their work schedules and what they experience are strong predictors of their intent to resign. This is because work schedules impose far-reaching constraints on the nurses' professional and social lives (Choi et al., 1986, 1989). So from 1983 to 1985, Rochester Methodist Hospital in Minnesota conducted an experiment with nurse scheduling to assess how various schedules might affect the retention of nurses.

The hospital's report of that experiment showed that various schedules did indeed reduce the nurses' job disappointment. But equally interesting is the behind-the-scenes report of the organization that elected to try such an experiment, and how it attempted to reconcile good management with the sometimes-

frustrating dictates imposed by "good science," or the experimental method. Both reports together tell an evolving tale of organizational change.

ROCHESTER METHODIST HOSPITAL

In many ways Rochester Methodist Hospital was an ideal site for such an experiment. Rochester Methodist Hospital, affiliated with the Mayo Clinic, was founded in 1954 as an acute-care facility. Methodist Hospital has always been staffed by only Mayo clinic physicians. The present facility with 791 licensed beds was designed in part for research (Sturdavant, 1960). The hospital was built as a "laboratory in which to study alternative designs of nursing units, hospital systems, and organization" (Trites et al., 1969).

The Mayo Medical Center and Methodist Hospital's reputation for quality of care and productivity is well known (Dietrich and Biddle, 1986; Fifield, 1988; Sunshine and Wright, 1987).

Methodist is more stable than many hospitals because it does not compete for patients. Mayo Clinic allocates admissions between Methodist and St. Mary's Hospital. During the period of the experiment, patient census declined from 85.3 percent occupancy to 65.5 percent, reflecting a national trend.

The nursing department at Methodist Hospital was also recognized for its leadership. The organization of the nonunionized department was traditional, with centralization of major functions such as scheduling, budgeting, and education. However, despite centralization, communication "from the bottom up" was consistently encouraged by top management, and nurses' suggestions were shared through the line managers.

Nurse turnover had been gradually reduced from 39.1 percent in 1974 for full-time nurses to 12 percent in 1983 (the beginning of the scheduling experiment), a time when many hospitals nationally were still having greater than 50 percent turnover (Prescott and Brown, 1987). Methodist's nursing success was documented in the 1983 report Magnet Hospitals, in which it was named one of the 41 "magnet hospitals" in the United States that had demonstrated outstanding success in attracting and retaining professional nurses (McClure et al., 1983). According to the study, conducted by the Academy of Nursing of the American Nurses' Association, these 41 hospitals are set apart by three common denominators:

-

Knowledgeable leadership providing for nursing input in policies affecting their practice,

-

Opportunity to practice professional nursing, and

-

Provision for professional growth.

The nursing department staff was also clearly interested in research. Methodist Hospital's philosophy read, "The institution has an obligation to its patients and professional groups to seek new knowledge and skills in the health care field." This hospital mission and nursing department staff's interest in research resulted in a 1978 study to review the feasibility of developing a nursing department program for systematic studies at Methodist Hospital (Egan et al., 1981). Several enabling factors were identified in that study, which suggested Methodist Hospital had the right climate for conducting research and implementing research results.

When the 1983 research project on nurse scheduling was approved, Methodist Hospital was governed by its own board of directors, whose backgrounds were primarily in fields of medicine, business, and law. The board was supportive of the nursing department, both having worked together for years, and recognized the department's accomplishments in the delivery of quality care, productivity, and nurse retention. All in all, Rochester Methodist Hospital was a progressive and even idyllic place in which to run an experiment.

THE TURNOVER PROBLEM

The scheduling problem addressed in the research project was how to maintain a qualified work force. This was not an immediate problem for Methodist Hospital, since its nurse turnover rate in 1983 was only 12 percent. However, there were undeniable signals that suggested a likely recurrence of a nursing shortage; one which would be of much longer duration than the cyclical shortages of the past.

Inability to maintain nursing manpower would affect quality of care. Patients coming from around the world to this tertiary care setting expected a competent nursing staff. Methodist's need to schedule and staff 35 nursing units 7 days a week, 24 hours a day, with limited turnover seemed difficult for those outside of nursing to understand. But the fact that companies like Atwork, which developed the scheduling software used by Methodist Hospital,1 spent years in developing these computer programs for nurses attests to the complexity that must be taken into account for quality patient care, concern for employees, and the maintaining of a budget.

Mayo Medical Center had experienced a nursing shortage in the early 1970s that precipitated the unprecedented action of closing hospital beds. This was difficult for the physicians. Studies in Minnesota and nationally predicted another shortage of nurses in the 1980s. These studies were conducted by such groups as the Minnesota Higher Education Coordinating Board and the Special Governor's Task Force on Nursing (1982). The report of the Governor's Task Force on Nursing called for "the health care industry to do a better job of retaining nurses in active practice if Minnesota is to deliver quality, cost-effective health care in the 1980's and beyond." The same task force listed the following trends indicating an upcoming nurse shortage:

-

the increasing demand for nurses to work in hospitals and nursing homes,

-

changes in hospital staffing patterns in response to technological and clinical development,

-

the decreasing population of high school graduates (predicted decrease of 34 percent between 1980 and 1992), and

-

the decrease in number of high school graduates who express an interest in nursing as a career.

The human-resource prediction model that was developed at Methodist also indicated a nursing shortage at the hospital unless retention could be maintained or improved upon.

The decision to go with the scheduling experiment was greatly influenced by the minutes of the Nurse Research Committee, which consisted of representatives from a cross section of nurses in the hospital. The minutes recalled that this research idea was not new:

In 1980, a Nursing Research Advisory Task Force was established with the purpose of identifying research study topics which would provide the most potential benefits to the Nursing Service Department, and to develop a framework for a Nursing Studies Department. The idea of a research project related to retention first appeared in the Research Advisory Task Force Minutes of October 1, 1981, when it was listed as a priority for study selection at Rochester Methodist Hospital.

In 1982 the hospital's nursing service department—to which all nurses belong—identified scheduling, continuity of care, and research as areas requiring attention. A number of criteria were also identified that would be applied to any nursing research project:

-

each research project would need to be successful and deemed important by the staff at all levels;

-

each research project should have some practical results;

-

each research results, when implemented, should be visible;

-

each research visibility should go beyond the institution;

-

each research project should mobilize and set up resources with the hospital, viewed positively by Mayo Clinic;

-

each research project should find its own funding; and

-

each project should contribute to an evolving and cumulative base for a research department.

As a result of applying these criteria, the immediate objective of Methodist's research was to develop, install, and evaluate alternatives that would improve the scheduling and staffing of nursing personnel in ways that were acceptable to them and that maintained the continuity and quality of patient care.

CHOOSING THE SCHEDULE

The scheduling research project consisted of the development, implementation, and evaluation of new schedules, or strategies, that would balance the needs and desires of nurses with cost and quality-of-care issues. No one schedule was favored before the research began. However, there was interest in the expanded use of the scheduling department computer.

The Research Steering Committee (consisting of researchers, the hospital administrator, the hospital's human resource director, the director of nursing, and the project coordinator) agreed that a literature review of information on scheduling and staffing be the first step of the research project. The review covered issues of staff morale, community, satisfaction, hospital image, cost, turnover and retention, and quality of care. The review identified 20 schedules or strategies being used in hospitals across the nation. Intense discussions occurred between members of the Research Project Committee (researchers) and the Nursing Executive Committee (nurse managers) regarding those 20 work schedules. In these discussions, the researchers wanted to test new schedules that would have transferability within and outside the organization. Nursing managers agreed, but favored those schedules that would be practical and realistic to implement at Methodist.

The scheduling supervisor described the 20 schedules and used a paper-and-pencil method to test them against a set of criteria previously identified as essential (see Appendix A). The results were brought to the Nursing Executive Committee for action, and 12 schedules were selected for further consideration and evaluation.

The general procedure was first to rank-order the scheduling options in terms of the estimated scores for each of the criterion variables. A sum of ranks across all the criteria was then computed for every scheduling option. Finally, a rank-ordering of those sums effectively enabled the Nursing Executive Committee to sequence the scheduling options from the one most likely to have the best effect on nurses and the quality and cost of care (by comparison with existing schedules) to the one that probably would have the weakest or poorest effects (see Table 1). In making its selection of experimental schedules, the Nursing Executive Committee also sought as much variety as possible among high-ranking schedules.

The Nursing Executive Committee and the Research Project Committees then selected three schedules to be implemented during the experiment: straight shifts, computerized scheduling (compflex), and select-a-plan. These schedules are described in a later section.

THE FIRST SNAG

It was at this point that the Nursing Executive Committee ran into difficulty with the research. It became clear that in order to test schedules objectively, units would have to be randomly assigned new schedules. This precluded choice or participative involvement—a fact that concerned all levels of nurse managers and nursing staff. The only incentive given to the staff was that if the experimental schedule met the criteria and was preferred over their previous schedules, staff could remain on the new schedule.

Good managers know it is virtually axiomatic that there must be good communication, support, mutual troubleshooting, and problem solving between management and staff. This was in fact the tradition at Methodist, which accounted for the esprit de corps and low turnover in the nursing staff. In sharp contrast, scientific research requires a commitment to an unbiased evaluation of new nurse schedules. Specifically, the experiment must be free of management interference. Otherwise, results of the experiment could be due not only to nurse schedules but also to management behavior.

Herein lies the conflict: Good management does not necessarily allow for good science. Testing new technologies in one's own organizational site has the advantage of ensuring that the technology—in this instance, nurse schedules—fits the setting. The disadvantage is that such a test may severely disrupt normal behav-

TABLE 1 Example of Comparison of Scheduling Options

|

Criterion |

Scheduling Option |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

|

Continuity |

10% |

27% |

19% |

19% |

25% |

0% |

18% |

0% |

20% |

Estimated rank |

|

|

4 |

9 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

8 |

3.5 |

5 |

3.5 |

7 |

|

|

Flexibility |

.32 |

.89 |

.25 |

.86 |

.41 |

.44 |

.70 |

.76 |

.98 |

Estimated rank |

|

|

2 |

8 |

1 |

7 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

9 |

|

|

Quality |

76 |

75.4 |

77.6 |

75.5 |

75.9 |

70.6 |

73.9 |

77.4 |

75.8 |

Estimated rank |

|

|

7 |

3 |

9 |

4 |

6 |

1 |

2 |

8 |

5 |

|

|

Sum of ranks for each option |

13 |

20 |

16.5 |

17.5 |

17 |

8.5 |

12 |

17.5 |

21 |

|

|

Rank order of the sums of ranks |

3 |

8 |

4 |

6 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

9 |

|

ior, which may in fact hurt the very group the technology is intended in help. Thus on the surface, good management and good science seemed to share a common concept, but putting the concept into operation was a different matter.

Despite misgivings, the Nursing Executive Committee decided to go ahead. At the first of what was to be many ''update'' meetings of all head nurses—first-line managers—random schedule assignments were made. Those head nurses in the selected units (i.e., regular nurse work stations) were given special recognition for their forthcoming participation. This recognition was not particularly well received. Individual reactions among head nurses at the meeting ranged from joy to extreme anger—so much so that the Nursing Executive Committee became apprehensive about the possibility of bias in the experimental outcome. Fortunately, however, true to their professionalism, each head nurse presented the new schedules fairly, with assistance from the scheduling department. The nursing staff reacted with the same range of emotions.

Because of these strong reactions, an unplanned facet to the research was added, which was to allow head nurses and staff the opportunity to submit anonymous comments about their schedules. The research coordinator on the experiment assembled the comments and shared them with the Nursing Executive Committee. The key to surviving a possible breakdown in morale at this point was trust in the dedication of the manager and the leadership of the department. These comments continued for the nine months of the intervention phase—that is, trying out new schedules—of the experiment. A review of the comments after the experiment still evoked pain on the part of the managers. These comments described the emotions of experiencing change at the personal, staff, and organizational levels.

The head nurses were definite losers in this change. They not only lost control of selecting schedules for their unit but also were placed in the most difficult position of bridging between employees and management. Although this situation improved with time, it contributed to stressful relations.

OTHER GLITCHES

After the research project started in 1983, four activities took place that significantly affected the hospital employees. These activities were important to the research project in terms of time commitments, potential employee morale problems, and lowering of managers' willingness to take risks.

First, pressure increased for immediate action on nurse scheduling. The hospital management and Board of Governors decided in 1983 to develop and conduct the first hospital-wide employee opinion survey. The results were generally positive and management was viewed favorably. However, the additional comment section contained 23 negative remarks (6 percent of the comments) about nurse scheduling. The implication of conducting an opinion survey was that the employees could expect immediate action in response to their comments; therefore, a scheduling experiment could have been seen by staff nurses as an unnecessary delay.

Second, the nursing department picked this time to computerize. Although the department had centralized scheduling in 1968, except for the schedules themselves, the department had kept limited data for managing projections. In the mid-1970s, increased record keeping of nurse statistics, such as turnover, manpower requirements, and costs, was begun; and by 1983 it was determined that some data automation was essential to manage this department of more than 1,000 employees. Therefore, in 1983, the nursing and management services departments began investigating scheduling systems that would produce reports, assist in nursing department record keeping, and automate the present schedules. Before this time, there had been no computer programs that could totally automate scheduling. In May 1984 a contrast was signed with Atwork for the Automated Nurse Scheduling System (ANSOS) computer program. The nursing management team had been consistently informed of the investigation into this system but choose not to involve staff nurses because it did not anticipate that the change would negatively affect the staff.

They were wrong. Implementation of change without staff involvement taught an invaluable lesson. Initially, ANSOS could not accommodate the size of the nursing staff. Therefore, it became necessary to use two separate programs, which precluded computer tracking of staff between the two programs. The lack of flexibility and integration resulting from this use of two independent computer programs fragmented the hospital into two separate systems, thereby affecting employee schedule exchanges and employees' ability to float or move to all units. The unexpected consequence of this change, in which the nursing staff viewed the computer as deciding their lives, was especially negative. The nurses became skeptical of the use of computers for scheduling.

The third activity that affected the research project was the implementation of the government's program of prospective diagnostic related groupings (DRGs) in October 1984. This program

should have had little effect on the already short length of hospital stays at Methodist. The effect it did have, however, was only to postpone the inevitable nursing shortage. This shortage came about because the decrease in the number of beds occupied (to 65 percent) and the length of inpatient hospital stay (by 0.3 days) caused nursing units to close. The hospital decided not to resort to layoffs. Soon, however, trying to stay on budget with too many nurses was one more problem for management to resolve.

Fourth was the prospect of a merger of Mayo Clinic, Rochester Methodist Hospital, and Saint Mary's Hospital. The potential merger was announced in 1985 during the study on scheduling and was completed in 1986. The major change was to form a common governance structure.

Nurse managers coping with the three other new activities just described, in addition to their normal activities and scheduling research, questioned whether the scheduling experiment should be continued. For this kind of research (and the implementation of its results) to work in a hospital, management needed to be strongly committed to the activity. As discussed, the requirements of good management and good research came into conflict.

NATURE OF THE NURSE SCHEDULING EXPERIMENT

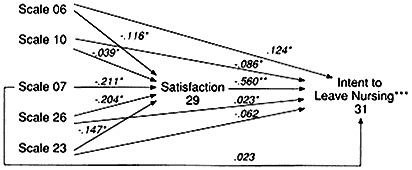

As mentioned at the outset of this discussion, disappointment in nurse scheduling indicates the process leading to resignation. Figure 1 shows how disappointments and discrepancies between what nurses expect and experience of their work schedules are strong predictors of nurses' intent to resign (Choi et al., 1989). Intention to resign has also been shown to have a direct and significant effect on turnover (Weisman et al., 1981). Satisfaction affects turnover through intention to resign (Weisman et al., 1981). Therefore, intention to leave is a critical intervening variable between satisfaction and actual turnover. Expressed by means of a parsimonious model, nurse turnover is a consequence of intention to resign, which is precipitated by dissatisfaction and discrepancies. Dissatisfaction itself is also a consequence of discrepancies.

Each discrepancy variable is a continuum, the two poles of which are represented by disappointment, which stems from expectation exceeding experience, and contentment, from experience superseding expectation. In the larger context of social theories, Davis (1962) and Durkheim (1951) both indicated that attitudes most likely to trigger action have to do with perceived discrepancy between a person's expectations and experiences, or the lack of

FIGURE 1 Operational model—predicting intention of nurses to leave nursing. Key: Scale 06: Discrepancy concerning work schedules creating a climate for ideal professional nursing. Scale 10: Discrepancy concerning work schedules allowing freedom for personal business. Scale 07: Discrepancy concerning work schedules that are predictable. Scale 26: Discrepancy concerning work schedules allowing social activities outside the hospital. Scale 23: Discrepancy concerning work schedules fostering relationships at and outside of work. Scale 29: General satisfaction. Scale 31: Intent to leave nursing altogether because of scheduling dissatisfaction. *P < .01, * * P < .001, and ***r2 = .3085.

integration between ends conceived and means available to achieve them. That is, dissatisfaction resulting from failing expectations—jolts that create disequilibrium—may very well induce change-seeking behavior.

Low nurse turnover, especially when the economy is sluggish, may lead to the mistaken conclusion that root causes of nurse turnover—schedule-induced dissatisfaction and disappointment—have vanished. The combination of uncorrected root causes and an improved economy would instigate nurse turnover. But redesigning work schedules may increase satisfaction and contentment, hence retention.

RESEARCH METHODS

To evaluate how different schedules affect retention, the research project committee and the nursing executive committee designed an experiment calling for three experimental groups and one control group. Each experimental and control group in turn consisted of three randomly selected nursing units. All told, 12 randomly chosen units were involved (random sampling process

described later). Two of the randomly selected experimental groups were randomly assigned a schedule; the remaining experimental group was assigned to design a schedule using its own criteria. Although the control group served only as a reference for comparison with the experimental groups, subjects in this group were administered similar data collection instruments and given the same opportunity to deliver anonymous comments about the experimental process. The experimental treatment was administered over a 40-week period. By staying within one hospital, experimental results would most likely not be confounded by differing hospital policies and management styles. Results reported here are from data collected before and after the full implementation of experimental schedules.

Three Experimental Schedules

The three experimental schedules were selected after a long process of examination and deliberation. Part of this process was discussed earlier. The first two experimental groups were assigned either straight shifts or computer-assigned scheduling (compflex). The third group designed its own schedule, labeled select-a-plan. To make the experiment as realistic as possible, none of the stations in the three experimental groups was allowed to exceed the normal budget; thus, results of the experiment did not involve a cost increase.

Under the straight-shift schedule, virtually all staff members of nursing units worked straight days, evenings, or nights. Staff members working days were expected to cover the evening and night shifts when vacancies occurred (e.g., during vacations). There were 63 nurses under the straight-shift treatment, of which 42 (67 percent) were registered nurses (RNs), the rest were licensed practical nurses (LPNs). The intent of the straight shift was to provide nurses with predictability and regularity, the lack of which threw their daily living out of synchronization.

The second schedule, compflex, aimed to provide both flexibility and control so that nurses could individually plan for their own schedules. Under the compflex schedule, a computerized system was used to generate a monthly schedule based on a combination of the unit's daily needs for the unit and staff requests. Staff members were allowed unlimited requests, though they soon demanded that a policy be implemented allowing for no more than one Friday evening or one Saturday night off per month. The requests were incorporated into the system; the schedule was

computerized. The scheduling department then reviewed the schedule to ensure that patient care needs would be met, and, if so, requests were granted on a first-come, first-served basis. This type of schedule did not have the predictability of a cyclical schedule but allowed for a great deal of input by individual nurses. Sixty-eight nurses were under this treatment of which 48 (72 percent) were RNs and the rest were LPNs.

Unlike the other two treatments, select-a-plan may be seen as much as a process as a schedule. Under the select-a-plan schedule, the staff on each of the stations developed from scratch the type of schedule to be used on that station. Each station selected two RNs and one LPN to develop the schedule based on the group's ideas. Minimum guidelines on budget and legal constraints were given to each work station, and assistance was offered by the nursing administration if the treatment group needed help. The schedule arrangement had to be voted and agreed upon by at least 80 percent of the nurses on each station.

Each of the three select-a-plan stations elected various combinations of 8-and 12-hour shifts. A certain portion of the staff had schedules of 8-hour shifts during the week and 12-hour shifts on the weekend. In those schedules, the staff worked every third weekend. Some stations also used a portion of straight days; others, a limited number of 12-hour shifts. All had some 8-hour shifts on rotating schedules. There were 59 nurses under this treatment: 30 (66 percent) RNs, the rest LPNs.

The nursing stations under the control plan continued to use the schedules as before the experiment. These schedules included 8-hour rotating shifts of day and evening, days and nights, and a limited number of straight evenings or nights. All staff members worked every other weekend.

Random Sampling

Data were collected from all RNs and LPNs regularly assigned to nursing stations. This intervention was primarily intended to monitor nurses on a station; thus random sampling was used for stations, not specific individuals.

Three general types of nursing units were identified through hierarchical cluster analyses of some 37 characteristics of each unit that were judged by head nurses and nursing administrators to be relevant to the scheduling of nurses. The analyses were performed using the CLUSTER program with the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) programming language (Anderberg, 1973; Milligan,

1980). Appendix B lists those 37 characteristics that were responsible for the cluster content in a statistically significant way. The sampling frame consisted of 18 medical and surgical nursing units stratified by general type of unit (clusters of 4, 7, and 7 units of types A, B, and C, respectively). Some highly specialized units such as intensive care and obstetrics and gynecology were excluded from the final sampling frame because there were too few of each to allow assignment of at least one unit to each of one control group and three experimental groups.

As many unit characteristics as possible were included to maximize the generalizability of study results. The units of each type also were stratified both by kind of floor architecture (circular or linear) and kind of care (medical or surgical). Type A units were all circular and surgical. Type B units were predominately surgical (5 of 7) and more frequently circular (4 of 7). Thus, a completely balanced sampling across the three stratification variables was not possible.

A stratified random sample of 12 units (three for each experimental and control group) was selected in such a way that each level of each stratification variable was represented at least once within each experimental and control group. That is, among the three units assigned to each group, the following unit characteristics were represented at least once: type A, type B, type C, medical, and surgical. Circular or linear types were represented more than once in each group.

Scales Used to Assess Experimental and Control Differences

Effects of treatment on the experimental groups relative to the control were gauged according to scores on 36 reliable scales (Appendix C). All scales, designed to be critical and relevant to scheduling-related issues and retention, were constructed through item analysis (Carmines and Zeller, 1979). The analysis consisted of reliability tests and factor analysis of questionnaire responses from all of the nurses (n = 792, 98 percent response rate) employed at the study hospital. The questions were developed with the help of two expert panels representing nursing education, scheduling, operations, and administration.

Each discrepancy scale score was derived from the sum of differences between nurses' own ratings on expectation and on experience for items specific to that scale. The direction and degree of difference across all items would indicate the level of disappointment of contentment.

Data Analysis

Beyond assessment and refinement of scale reliability, an analysis of variance was performed to ascertain that the experimental groups were significantly different from the control group, before and after implementing the experimental treatment.

FINDINGS

Immediate Results

Results shown in Table 2 indicate that there were significant differences in scores across 6 of the 36 scales between the experimental and control groups after the experimental treatments were administered. In contrast, before the intervention, there was a difference in only one scale—experience in privacy of work—which was judged to be inconsequential. The composition and reliability of each scale, out of the total of 36 that discriminated significantly between the groups, is shown in Appendix D.

The select-a-plan scheduling group was significantly different from the control in four of the 36 scales: expectation of a work schedule that allows for communication with day department (scale

TABLE 2 Significant Differences Across 36 Scales Relative to the Control Group: RNs and LPNs

4), expectation of being able to control one's schedule (scale 5), discrepancy concerning work schedules creating a climate for ideal professional nursing (scale 6), and discrepancy concerning work schedules that are predictable (scale 7) (see Table 2). The compflex and straight-shift groups were significantly different from the control group in two identical scales: sense of one's own marketability (scale 2) and expectation of staff teamwork and friendship (scale 3). Thus, the select-a-plan group was affected most by the experiment.

When compared with the other two groups, the select-a-plan group also showed significantly less disappointment (discrepancy) in a key variable—discrepancy concerning work schedules creating a climate for ideal professional nursing (scale 6). This particular scale was shown previously to have a direct and significant effect on the intention to leave nursing (see Figure 1). The select-a-plan group showed no increase in sense of marketability and had lower levels of expectation in communications with other departments. The select-a-plan group also showed less disappointment, previously shown to be a predictor of intention to resign (Figure 1).

When the groups were stratified into RNs and LPNs, the RNs in the experimental group scored differently from the RNs in the control group on two of the 36 scales (see Table 3). When RNs from all three experimental groups were treated as a group, they perceived a greater sense of their own marketability (scale 2). On a group-to-group comparison, only compflex RNs were shown to have a significantly higher sense of marketability than the control. They also had greater expectation of a schedule that allowed more continuity of care (scale 8).

In contrast, Table 4 shows that LPNs in the experimental groups differed from LPNs in the control group on four scales: less expec

TABLE 3 Significant Differences Across 36 Scales Relative to the Control Group: RNs Only

|

|

Before Treatment |

After Treatment |

|

Straight Shift |

|

|

|

Compflex |

|

Scale 2 (+) Scale 8 (-) |

|

Select-A-Plan |

|

|

|

Key: Scale 2 = sense of one's own marketability; and Scale 8 = expectation of a work schedule that allows continuity of care. (+) = scored higher than control. (-) = scored lower than control. |

||

TABLE 4 Significant Differences Across 36 Scales Relative to the Control Group: LPNs Only

|

|

Before Treatment |

After Treatment |

|

Straight Shift |

|

|

|

Compflex |

|

Scale 9 (-) Scale 10 (-)a |

|

Select-A-Plan |

Scale 1 (+) Scale 11 (+) |

Scale 9 (-) Scale 5 (-) |

|

|

|

Scale 7 (-)a |

|

Key: Scale 1 = experience of a work schedule that allows privacy at work; Scale 5 = expectation of being able to control one's schedule; Scale 7 = discrepancy concerning work schedules that are predictable; Scale 9 = expectation of a work schedule that fosters relationships at and outside of work; Scale 10 = discrepancy concerning work schedules allowing freedom for personal business; and Scale 11 = expectation of a work schedule that allows privacy at work. (+) = scored higher than control. (-) = scored lower than control. a Indicates less disappointment or more contentment. |

||

tation of being able to control one's schedule (scale 5), less disappointment (discrepancy) in the predictability of work schedules (scale 7), less expectation of work schedule that fosters relationships at and outside of work (scale 9), and less disappointment (discrepancy) concerning work schedules allowing freedom of personal business (scale 10).

Later Results

The immediate results just discussed, which reflect what happened shortly after the experiment was implemented, were consistent over time; disappointments were lowered and satisfaction with other facets of nursing were increased in the experimental groups relative to the control groups. Over time, lower teamwork and a higher sense of one's marketability—two unintended negative consequences—disappeared.

A particularly important finding was that there were no significant statistical differences in actual turnover between experimental and control groups after the treatments. (Turnover data included transfers to another nursing unit within the hospital as well as voluntary resignations from the hospital.) The range of transfers for all groups was between 7 percent and 8 percent; resignations were between 2 percent and 4 percent for the experimental groups, but 7 percent for the control group. Although the

data seemed to favor retention in experimental groups, the number of turnover cases was too small to generalize with statistical confidence.

The actual turnover numbers continued to favor the experimental groups two years after the experiment was completed. Again the numbers were too small for statistical tests. By the third year the actual turnover rate became similar between the experimental and control groups.

The study also examined the relationships between scheduling, cost of care, and quality of care. These relationships are complex and go beyond the scope of this paper. In brief, the study showed that staffing, not scheduling, affected cost of care. Scheduling also had little impact on continuity of care, the proxy that was used to measure quality.

DISCUSSION

Overall, the experiment was effective in that varying work schedules produced different consequences. Virtually no difference existed between the study groups (all randomly selected) before the intervention began. The differences between experimental and control groups after intervention attest to the importance of schedules or schedule-related issues. The select-a-plan treatment showed the greatest experimental impact, judging by the number of changes on the units detected by the scales. By the end of the interventions after roughly 40 weeks, all but one of the nine experimental stations voted to continue their respective experimental schedules. The lone exception was a straight-shift station. Furthermore, none of the three types of experimental schedules appeared to have been viewed negatively by the nursing staff. This conclusion was supported further by a very low turnover rate. This low rate may be due in part to the poor job market when the experiment took place in 1984–1985. Of greater significance, perhaps, was that some of the root causes of turnover—two of the five discrepancy variables—were affected by the experiment in such a way that would favor retention (Figure 1).

One of the unanticipated consequences that appeared shortly after the experiment began was the nurses' increased sense of their own marketability in two of the three study groups. Thus, ironically, an experiment that was intended to find ways to retain nurses may have also encouraged some nurses to seek employment elsewhere. Why nurses in the two experimental groups felt more marketable is a matter of speculation. The classic Hawthorne

effect may be ruled out as a cause because all of the groups, including the control, received about the same amount of research attention. A more likely explanation might be that the nurses in the compflex group were reinforced by a new sense of control derived from the legitimatized right to negotiate their own work schedule. They probably also chose to be on new schedule(s) that gave them positive experiences, which in turn, enhanced their self-esteem and sense of marketability.

While choice of schedule may be relatively limited for some under the straight-shift format, for others, being on a straight-shift schedule may have approximated the ''ideal'' work schedule. (For example, straight days are more likely to be synchronized with the schedules of people outside the hospital.) At a minimum, straight shifts offered a regular work schedule whether it was day, evening, or night. There were those nurses on straight evenings or straight nights who preferred such shifts because they coincided with the work hours of their spouses or because shifts had smaller and potentially more cohesive work groups. Perhaps most important is that straight shifts allowed for a less ambiguous relationship between seniority and attainment of an ideal schedule. These combined factors possibly enhanced the self-esteem of nurses, which in turn may have heightened self-perceived marketability as well.

Another consequence of the experiment was a lessening of teamwork under compflex and straight-shift schedules. This may be explained again by an individual's increased power to negotiate one's schedule without consulting other nurses on the unit. Under the straight-shift schedule, it could also be explained by the lack of continuity in nurses between shifts. That is, in the strictest sense, straight shifts fostered a sense of nursing identity by shifts rather than by units. Because nurses did not span shifts, the overall cooperation on the unit suffered.

Over time, the lack of teamwork and the increased sense of marketability disappeared. Returning teamwork and nurses' sense of marketability to their former states had to do with a deeper understanding of how one's schedule changes affected others on the unit. Once the process was understood, teamwork improved again and the nurses' own sense of marketability also returned to the normal level.

Over time, straight shifts could not be kept in the strictest sense at this acute-care hospital because nursing management desired experienced nurses on all shifts. The decision to honor seniority—that is, senior nurses having first pick of schedules—

ran counter to the need to schedule experienced nurses on all shifts. Methodist nursing units were small, 14–30 beds, which required a small staff and, thus, less flexibility. Therefore, an increased budget or overhiring would have been required to remain on a strict straight shift. By rotating some skilled nurses across shifts so that none was assigned exclusively to a particular shift, the we/they dichotomy between nurses on different shifts of the same stations disappeared. Thus, the necessary continuity between shifts was restored, but the straight shift became less attractive to the nurses who had to rotate to fill in for vacancies.

The intended effect of the entire experiment was, in part, to reduce discrepancies between nurses' experiences and expectations of their jobs, root causes of turnover. Less disappointment, or more contentment, was most evident with the select-a-plan group, which improved its discrepancy scores over the course of the experiment by lowering expectation scores relative to that of experience. That group showed less of the disappointment (scale 6) that contributed directly to the intention to resign. Data taken before the experiment had shown a high level of expectation—and experience as well—among the majority of the nurses. A scheduling experiment would have had to be very powerful before it could have improved on the already high scores on expectation and experience among this group of nurses. Quite unexpectedly, however, discrepancy scores did improve—that is, experience superseded expectation—by the lowering of nurses' expectation scores. When nurses lowered their high expectations, this may have been a healthy sign that individual nurses believed they could bring about greater consistency between expectation and experience. Despite the generally high score of the nurses in expectation, experience, and satisfaction, scheduling as an experimental treatment was able to bring about several significant changes; this attests to the importance of scheduling to nurses.

The after-treatment differences of select-a-plan relative to the other two experimental groups shows that select-a-plan appeared to have best met the objective of retaining nurses without increasing costs. The select-a-plan group was able to reduce discrepancies (disappointments) because the nurses significantly lowered their expectations of being able to (1) control their own schedules (scale 5), and (2) communicate with other departments (scale 4). These lowered expectations for the select-a-plan group may be a consequence of the group's having to construct a work schedule that was approved by at least 80 percent of the group. This process of deliberation may have exposed the nurses to the difficul-

ties of making a schedule work. Thus, mere exposure might have led to a certain understanding, if not acceptance, that some elements in the practice of clinical nursing might elude personal control. Perhaps these sets of experiences and exposures, particularly obvious through the select-a-plan group process, contributed to the lowering of expectations and, as a result, reduced disappointments.

The three experimental treatments did not have a statistically significant direct effect on retention (as measured by different indices of intention to resign), although the experiment did have significant effects on predictors, or root causes, of intention to resign. Several factors may have mitigated the direct effect of the experiment on resigning: (1) the period of experimentation with the new schedules (1984–1985) was characterized by a poor job market, which made job changes less feasible; (2) nurses in the study knew that despite their desire for immediate changes, the experimental schedules were to last no longer than 9 months; and (3) the nurses in the study understood that a primary purpose of the experiment was to improve the quality of their professional and personal lives. Although circumstances discouraged nurses from actually resigning, the experiment did significantly affect root causes of potential resignations. It may be possible to infer from this that if the experiment had been continued, significant differences in retention between nursing units in the study would have been evident.

The lower turnover rate among the experimental groups two years after the experiment—including the one straight-shift station that voted against continuance after the experiment—speaks to the importance of scheduling. But the turnover rate was more similar across all study groups by the third year (1988) after the experiment. It should be noted that nursing management had expected a greater increase in nurse turnover on a hospital-wide basis in 1988, since many of the requested schedules had not been implemented. However, the following reasons may account for the less-than-expected turnover: the scheduling task force became a permanent scheduling advisory committee with representation from all service areas; units felt there was a more flexible attitude in the scheduling department despite limited changes in policy; nurses were aware of a scheduling task force between the two merged hospitals and their efforts to find means of implementing new schedules; and some staff energy was diverted away from scheduling to the ongoing merger. Thus, nurses may have adopted a wait-and-see attitude.

Of interest was the influence of the treatments on RNs in the experimental groups compared with RNs in the control group. RNs showed changes on only two scales. But LPNs in the experimental groups relative to their counterparts in the control group showed four scale changes. The relative marketability of RNs to that of LPNs may explain the difference in the effects of the scheduling changes. Hence, the changes may have greater impact on LPNs than RNs.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

From the perspective of hospital administration and policy, it should be clear that the experiment did not cause significant nurse turnover. The experiment answered the feasibility question positively and also indicated that none of the three new schedules is likely to be negatively received by nursing personnel. This latter feature is particularly important considering the frequency with which well-meaning interventions unintentionally hurt the very target population they are designed to help.

Results of this experiment should give hospital administrators confidence to proceed in implementing new types of schedules, knowing that cost and turnover probably will not be affected when conditions are stated beforehand to the staff. Results should also alert decision makers to be aware of the potential risks involved—for example, enhancing nurses' sense of marketability, which indeed may lead to turnover—when the reduction of discrepancies between job expectations and experience (disappointments) becomes especially successful.

The three experimental schedules provide variety and give hospitals different options. Variety may be crucial even for just one hospital to accommodate the diverse units of modern hospitals. A single-schedule format would probably not suffice to meet the many different needs of patients and staff.

Of the three experimental schedules, select-a-plan offered the most flexibility in tailoring a schedule for nurses on a unit. The results of this treatment also appeared particularly encouraging in inhibiting intention to resign. Overall, the success of select-a-plan proved the soundness of allowing nurses to design their own schedules. However, this success is not inevitable. Clear goals, criteria, and boundaries, for example, emphasis on budget limitations and quality of care must be communicated first. A successful implementation is predicated on the assumption that nurses on the unit are willing and able to design and agree upon a sched-

ule. The degree to which such an assumption can be met depends on the specific unit involved and the time allotted to the unit for such activity.

The results of the experiment did not induce widespread changes as gauged by the 36 scales that measured job satisfaction. From a policy perspective, it may be concluded that this was a positive sign, because the experiment did not induce large-scale upheaval. Changes that were statistically significant involved a few variables, some of which were particularly relevant to retention. However, had the study been conducted in a hospital where nurses were less content, there could indeed have been more significant changes.

CURRENT SITUATION

After the experiment, 16 nursing units requested to design and implement their own select-a-plan schedules. These schedules allowed more ways for nurses to try new ideas and provided for a variety of schedules.

However, two factors have delayed the implementation. First, federal wage and hour regulations have been tightened for nonexempt employees2 so that the desired select-a-plan schedule would cost, for the entire nursing department (RNs, LPNs, and ward secretaries), $700,000 more in 1989 than in 1988 and would escalate each year with salary increases. Hospital decision makers are exploring solutions such as going exempt and changing the starting day of the work week. Second, a consequence of the hospital merger requires that new and innovative scheduling decisions be jointly made between the two hospitals. This arrangement could curtail the nursing department's ability to develop its own schedules.

Other hospitals are using variations of the select-a-plan process. The difference is that they may not have applied the aforementioned criteria (see Appendix A) used in the initial evaluative review of schedules. This evaluation is critical because it identified the potential problems and necessary corrective steps that were then suggested by hospital management, the human resource department, and nursing management.

A LAST WORD ON MANAGEMENT

The Head Nurse

It bears repeating that it is crucial for the head nurse to be involved in, and committed to, both planning and implementa-

tion. Regardless of the type of organization, the nursing staff needs a regular, consistent process of communication between various departments. The head nurses, as first-line managers, are the necessary link for the following reasons.

The new schedules, especially select-a-plan, reflected decentralization, which made frequent communication all the more necessary between management and staff nurses. Head nurses were the critical link between the key parties.

Decentralization also represented change, which many employees resented even though quality of care and services continued. The resentment against change demonstrated that upper management could not predict employee response as well as the head nurses could. For example, it seemed logical to outside nursing managers that a schedule that gave each employee freedom to make unlimited requests for changes (compflex) had to be attractive to nurses. But upper management failed to recognize that schedules needed to be predictable, and that more aggressive employees took advantage of the freedom, causing resentment in others. Only the head nurses, who knew their employees personally, could and did accurately predict staff reaction.

WHY THE NEW SCHEDULES WORKED

There are strong disincentives for hospitals to adopt new schedules. The planning process, assessment of readiness, and achieving consensus on what schedule to implement are time-consuming and stressful and compete with other demands. As a result, there is a built-in reluctance to commit to such an endeavor.

In retrospect, on this project, management was less involved in solving a problem than it was in preventing a problem from happening. Through the process of experimentation, the potential for disaster was so apparent that the following ingredients appeared essential for the project to succeed: (1) leader commitment to take risks, (2) a steadfast vision of what is feasible and desirable, and (3) a steadfast support of personnel undergoing change. Also critical to the process was that Methodist was not fighting for survival. It had the freedom to find ways to make improvements.

Again in retrospect, it also became apparent that a minimum of nine months was needed for implementation and adjustment of schedule changes. Commitment and continuity are key ingredients. Such a project should probably not be attempted if top-level management is undergoing personnel changes. When change can be implemented along regular channels without having to create

new or temporary structures, communication and trust are more likely to result.

Some of the changes in schedules and scheduling were not planned but evolved by trial and error. Both select-a-plan and compflex tried various combinations of scheduling arrangements. The evolution was aided by the scheduling department and by computerscheduling software, which were essential to the realization of select-a-plan and compflex schedules.

Because specific criteria of schedule selection and implementation were put in place for the select-a-plan group, the risk to management of allowing staff freedom to develop these schedules was lessened. The trust in staff to respect limits imposed by the criteria paid off.

Several other organizational factors were important, and these were considered before the experiment was implemented. First, it was recognized from the start that nurse scheduling and staffing was an issue of concern to every new employee. Thus, an experiment on scheduling would probably be well received. Second, it was recognized that management staff working on the research was already assigned a heavy workload. Even with the employment of a full-time coordinator, extra time would most likely be needed from specific staff members for the project to succeed. Third, the diverse composition of Methodist's nurses made fair play a challenge in implementing schedule changes. The experimental schedules were designed as much as possible to give nurses with seniority the first pick, even though some of these nurses had been at the hospital for 10 or more years and were unlikely to leave. The recognition of seniority and respect for fair play may also have contributed to the acceptance of the experiment.

For the future, two changes are foreseen. If new schedules continue to evolve at Methodist they will be kept, provided that they demonstrate improvement over existing schedules. It is possible then to have a large variety of schedules at the hospital rather than the standard two before the experiment started. The other anticipated change is an increasingly stronger role for head nurses in schedule selection. This should reduce the erosion of authority as a result of implementing new schedules.

NOTES

|

|

Act and the subsequent amendment of 1986—which applies to hospitals—are paid by the hour and entitled to overtime pay. Exempt and nonexempt statuses are conferred based on the nature of work, responsibility, and salary. Most nurses at Rochester Methodist Hospital are of nonexempt status. But they are eligible for exempt status, which is generally, though not always, represented by executive nurses or nurses with a certain level of education (e.g., RNs). By regulation, there is less flexibility allowed by the Fair Labor Standards Act for nonexempt employees. Thus, despite the attractiveness of the select-a-plan (SAP) to the nurses—because of its flexibility—and the willingness of the hospital administration for nurses to adopt SAP, accommodating the constraints imposed by nonexempt status and flexibility inherent in SAP presents continuous challenges yet to be fully met. For a comprehensive treatment of exempt and nonexempt status, refer to Murphy and Azoff (1987). |

REFERENCES

Academy names 41 "magnet" hospitals because of their "demonstrated success" in attracting and retaining nurses. 1983. American Nurse 15(2):1.

Anderberg, M. R. 1973. Cluster Analysis for Applications. New York: Academic Press.

Carmines, E. G., and R. Zeller. 1979. Reliability and Validity Assessment. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications.

Choi, T., H. Jameson, M. L. Brekke, R. O. Podratz, and H. Mundahl. 1986. Effects on nurse retention: An experiment with scheduling. Medical Care 24(11):1029–1043.

Choi T., H. Jameson, M. L. Brekke, J. G. Anderson, and R. O. Podratz. 1989. Schedule related effects on nurse retention. Western Journal of Nursing Research 11(1):92–107.

Davis, J. C. 1962. Toward a theory of revolution. American Sociological Review 27:5–19.

Dietrich, H. J., and V. H. Biddle, eds. 1986. The Best in Medicine. New York: Harmony Books.

Durkheim, E. 1951. Suicide (J. A. Spaulding and G. Simpson, translators) New York: Free Press.

Egan, E., B. McElmurry, and H. Jameson. 1981. Practice-based research: Assessing your department's readiness. Journal of Nursing Administration 11(10):26–32.

Fifield, F. F. 1988. What is a productivity-excellent hospital? Nursing Management 19(4):32–40.

Final Report and Recommendations. 1982. Governor's Task Force on Nursing, State of Minnesota, p. 1.

Higher Education Coordinating Board (HECB). 1982. Post-Secondary Education Enrollment Projection, St. Paul, Minnesota.

McClure, M., Paulin, Sovie and Wandelt. 1983. Magnet Hospitals: Attraction and Retention of Professional Nurses. Kansas City, Mo.: American Nurses' Association.

Milligan, G. W. 1980. An examination of the effect of six types of error perturbation on clustering algorithms . Psychometrika 45:325.

Murphy, B. S., and E. S. Azoff. 1987. Guide to Wage and Hour Regulation: A Practical Guide for the Corporate Counselor. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of National Affairs.

Prescott, P. A., and S. A. Bowen. 1987. Controlling nursing turnover. Nursing Management 18(6):60–66.

Sturdavant, M. 1960. Intensive nursing service in circular and rectangular units compared. Hospitals 34(14):46–48ff.

Sunshine, L., and J. W. Wright. 1987. The Best Hospitals in America: The Mayo Clinic and Hospitals. Henry Holt and Company: New York. pp. 178–184.

Trites, D. K., F. Galbraith, J. Leckwart, and M. Sturdavant. 1969. Radial nursing units prove best in controlled study. Modern Hospital 112(4): 94–99.

Warner, M. 1976. Scheduling nursing personnel according to nursing preference: Mathematical programming approach. Operations Research 24(5):842–857.

Weisman, C. S., C. Alexander, and G. Chase. 1981. Determinants of hospital staff turnover . Medical Care 19:431.

APPENDIX A Criteria Used to Evaluate Schedules

-

Continuity of schedule: An estimate of the number of times an employee was scheduled to work consecutive days. A base standard of minimal continuity was identified as three consecutively scheduled days. The scale score ranged from 1 (low continuity) to 7 (high continuity).

-

Cost of schedule: An estimate to determine the compliance with the budget standard set for the unit. The number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) required for adequate unit coverage was determined and the impact of the schedule on benefits for staff was calculated. The schedules were listed in the order of low to high cost.

-

Ease of hiring: An estimate of the ease of hiring nurses into the positions (shift rotation patterns and number of days to work within a pay period) dictated by the schedule. Each position, which consisted of a pattern of hours worked, was given a score from

-

1 (low) to 7 (high) and these scores were added together for a unit score.

-

Unit internal community: An estimate to determine the maximum and minimum number of potential staff an employee would work with on the unit.

-

Schedule management: An estimate of the amount of time for ongoing management of the schedule. (Included time for manual work by personnel/payroll and time necessary to keep the schedule operational).

-

Quality of care: Estimates were made of the scores on six scales that would be used to measure quality of care on nursing units after the schedules were implemented. Quality scales included items on physical care, assessment, non-physical care, evaluation of care, etc.

-

Staff morale: An estimate of the effect of the new schedule on staff morale and satisfaction. Behaviorally anchored scales were developed that allowed for varying levels of nurse behavior ranging from 1 (low morale) to 9 (high morale).

-

Schedule flexibility: An estimate of the ability of staff to change schedules through exchanges, etc. The scale ranged from 0 (meaning no flexibility) to 1 (meaning maximum flexibility).

-

Schedule satisfiers/dissatisfiers: An estimate of the number of satisfiers and dissatisfiers within each schedule. The range was from-5 (meaning many dissatisfiers) to +5 (meaning many satisfiers). An example of a satisfier was straight-day shifts with the weekend off. An example of a dissatisfier was working a day/evening rotating shift and working every Friday evening before a weekend off.

-

Schedule implementation: An estimate of the amount of time needed to implement a schedule on the unit. Included were hiring of new staff to fill positions, developing the base pattern, determining the number of full-time and part-time employees for the schedule, etc.

-

Compliance with personnel policies and regulatory requirements: An evaluation of compliance/noncompliance of each work schedule with department policies and regulatory requirements.

APPENDIX B Significant Characteristics of Nursing Units that were Used to Identify Empirical Types of Nursing Units by Means of Cluster Analyses

-

Ways that ward secretarial services are provided

-

Percent and FTE budgeted by job category (RN/LPN/NA)

-

Average number of patient admissions

-

Average acuity

-

Percent and FTE actual cost by category (RN/LPN/NA)

-

Actual hours per workload index

-

Average patient census

-

Average number of patients of types 1, 2, 3, and 4

-

Total number of beds on the unit

-

Percent shifts on days, evenings, nights

-

Average percent patient occupancy

-

Average number of patient dismissals/day

-

Percent full-time and part-time by category (RN/LPN/NA)

-

Unit architectural design

-

Percent rotating shifts

-

Average number shifts floated in by category (RN/LPN/NA)

-

Average number shifts floated out by category (RN/LPN/NA)

-

Average number of patients over 65

-

Average length of stay of nurse staff

-

Percent straight shifts

-

Average number of tests done at Mayo Clinic

-

Average number of patient transfers/day

-

Percent and number of employees hired into unit

-

Percent and number of employees terminating from unit

-

Percent and number of employees transferred out of unit

-

Percent and number of employees on LOA by job category (RN/LPN/NA)

-

Average number of clinical tests done for patients while hospitalized

-

Frequency and number of student nurses on unit

-

Percent and number of employees transferred into unit

-

Average length of stay of patients

-

Length of stay of Head Nurse

-

Number of patient referrals

-

Number of physician services assigned to unit

-

Mayo Clinic support services

-

Primary physician services assigned to unit

-

Medicus unit quality assurance scores

-

Average number of patient falls

APPENDIX C Questionnaire Scales Reliability Related to Job Satisfaction

Scale 1: Experience of a work schedule that allows privacy at work Reliability = .92

Scale 2: Sense of one's own marketability Reliability = .86

Scale 3: Experience of a work schedule that fosters staff team work and friendship on the unit Reliability = .80

Scale 4: Expectation of a work schedule that allows communication with key departments Reliability = .93

Scale 5: Expectation of being able to control one's schedule Reliability = *

Scale 6: Discrepancy concerning work schedules creating a climate for ideal professional nursing Reliability = .91

Scale 7: Discrepancy concerning work schedules that are predictable Reliability = .80

Scale 8: Expectation of a work schedule that allows continuity of care Reliability = .70

Scale 9: Expectation of a work schedule that fosters relationships at and outside of work Reliability = .88

Scale 10: Discrepancy concerning work schedules allowing freedom for personal business Reliability = .87

Scale 11: Expectation of a work schedule that allows privacy at work Reliability = .95

Scale 12: Expectation of a work schedule that creates a climate for ideal professional nursing Reliability = .96

Scale 13: Experience of a work schedule that creates a climate for ideal professional nursing Reliability = .88

Scale 14: Experience of a work schedule that allows communication with key departments Reliability = .92

Scale 15: Discrepancy concerning work schedules allowing communication with key departments Reliability = .91

Scale 16: Expectation of a work schedule that allows freedom for personal business Reliability = .92

Scale 17: Experience of a work schedule that allows freedom for personal business Reliability = .93

Scale 18: Discrepancy concerning work schedules allowing privacy at work Reliability = .90

Scale 19: Expectation of a work schedule that is ideal for what I want Reliability = .80

Scale 20: Expectation of a work schedule that fosters communication and teamwork on the unit Reliability = .90

Scale 21: Discrepancy concerning work schedules fostering communication and teamwork on the unit Reliability = .86

Scale 22: Experience of a work schedule that fosters relation ships outside of work Reliability = .84

Scale 23: Discrepancy concerning work schedules fostering relationships outside of work Reliability = .88

Scale 24: Expectation of a work schedule that does not get in the way of social activities outside of the hospital Reliability = .85

Scale 25: Experience of a work schedule that allows social activities outside the hospital Reliability = .83

Scale 26: Discrepancy concerning work schedules allowing social activities outside the hospital

Scale 27: Perceptions that work schedules reflect respect and sensitivity toward work and personal lives of nurses Reliability = .91

Scale 28: Perceptions that hospital provides potential for nurses, professional growth Reliability = .86

Scale 29: General satisfaction Reliability = .85

Scale 30: Satisfaction with being a nurse Reliability = .84

Scale 31: Intent to leave nursing altogether Reliability = .91

Scale 32: Intent to change nursing jobs within or outside hospital Reliability = .89

Scale 33: Intent to leave hospital, but not due to dissatisfaction Reliability = .95

Scale 34: Intent to resign job Reliability = .82

Scale 35: Expectation of being able to change one's own schedule Reliability = *

Scale 36: Experience of a work schedule that may influence my leaving the hospital or nursing Reliability = *

|

* |

Reliability coefficient, using Cronbach's alpha, less than .70; but single factor solution was obtained through factor analysis. |

APPENDIX D Scales that Discriminated Significantly between Experimental and Control Groups

Scale 1. Experience of a Work Schedule That Allows Privacy at Work (Reliability = .92)

I experience this at the hospital: A work schedule that allows me time away from

-

nurses on my unit

-

the head nurse on my unit

-

patients on my unit

-

supervisors on my unit

-

physicians on my unit

-

unit activities

Scale 2. Sense of One's Own Marketability (Reliability = .86)

Without relocating, what are the chances that you could

-

obtain another job that uses your skills and abilities?

-

obtain another job that pays as much as your present job?

-

obtain another job that is as easy or easier to commute to as your present job?

-

obtain another job that has similar or better hours than your present job?

-

obtain another job that has similar or better working conditions than your present job?

Scale 3. Experience of a Work Schedule That Fosters Staff Teamwork and Friendship on the Unit (Reliability = .80)

I experience this at the hospital:

-

staff members on my unit that enjoy working with each other

-

a work schedule that fosters a sense of belonging on my unit

-

a work schedule that promotes loyalty among staff on the unit

-

a clear idea of what to expect from the staff with whom I work

-

a work schedule that fosters my sense of teamwork on the unit

-

a work schedule that helps friendships form on the unit

Scale 4. Expectation of a Work Schedule That Allows Communication with Key Departments (Reliability = .93)

I currently expect this from a first-rate hospital: A work schedule that allows me the opportunity to communicate with

-

personnel department

-

health services

-

nursing education

-

nursing administration

-

nursing library

-

community agencies

Scale 5. Expectation of Being Able to Control One's Schedule (Reliability = .80)

I currently expect this from a first-rate hospital:

-

a work schedule in which I am able to make changes by negotiating with other staff nurses

-

a work schedule that is more likely to be determined by the exchanges I make with my co-workers than by the scheduling department

-

a level of satisfaction, while working on my unit, that is dependent more on day-to-day staffing than on the work schedule assigned to me by the scheduling department

-

opportunity for me to suggest adjustments to my work schedule before it is finalized by the scheduling department

-

a work schedule in which I am able to make changes by negotiating with my head nurse

Scale 6. Discrepancy Concerning Work Schedules That Create a Climate for Ideal Professional Nursing (Reliability = .91)

Discrepancy between expectation and experience concerning

-

sufficient staff when I am on duty for me to provide quality of care

-

a work schedule that allows me to obtain information that is necessary to my providing care

-

replacement by a nurse when someone on my unit is absent (due to illness, vacations, etc.)

-

sufficient equipment on any work schedule, including weekends, for me to provide quality care

-

a work schedule that allows for the right balance of independence and supervision when I am providing care

-

a flexible work schedule without jeopardizing cost and quality of care

-

a clear idea of what to expect from staff with whom I work

-

a work schedule that allows me to give the most efficient care to my patients

-

a work schedule that allows me to get adequate rest

-

a work schedule that will not lower the quality of care I can provide

-

a work schedule that allows me time to consult with other health professionals

-

a work schedule that allows me to do dismissal planning for patients

-

good supervision even if my head nurse is not there

-

a work schedule that facilitates the opportunity to communicate directly with other nurses regarding the plan for my patients

-

clinically competent staff nurses on my unit

-

a work schedule that is practical

-

a work schedule that allows me to give nursing care the way I choose

Scale 7. Discrepancy Concerning Work Schedules That are Predictable (Reliability = .80)

Discrepancy between expectation and experience concerning a work schedule that

-

is regular

-

is predictable

-

allows me to plan months in advance

Scale 8. Expectation of a Work Schedule That Allows Continuity of Care (Reliability = .70)

I currently expect this from a first-rate hospital:

-

a work schedule that is flexible enough to allow me to care for the same patients several days in a row, if I am willing to change my personal plans in order to provide such care

-

a work schedule that allows patients to receive care from the same nurse on the same shift for several days in a row

-

a work schedule that allows me consistent contact with the same patients during their hospital stay

Scale 9. Expectation of a Work Schedule That Fosters Relationships at and Outside of Work (Reliability = .88)

I currently expect this from a first-rate hospital:

A work schedule that fosters relationships outside of work that are a positive influence on my personal life and make me happy

A work schedule that fosters relationships outside of work that

-

are a positive influence on my work

-

are a positive influence on my personal life

-

make me happy

-

make me want to stay in the hospital

Scale 10. Discrepancy Concerning Work Schedules Allowing Freedom for Personal Business (Reliability = .87)

A work schedule that does not get in the way of

-

doing banking

-

going out for snacks, dinners

-

seeing a lawyer, tax accountant

-

shopping for clothes, housewares, hardware

-

getting the house/apartment repaired/refurnished

Scale 11. Expectation of a Work Schedule That Allows Privacy at Work (Reliability = .95)

I currently expect this from a first-rate hospital: A work schedule that allows me time away from

-

nurses on my unit

-

the head nurse on my unit

-

patients on my unit

-

supervisors on my unit

-

physicians on my unit

-

unit activities