Until January 1, 1994, the day that the amended Age Discrimination in Employment Act forbade higher education institutions from imposing a mandatory retirement age on faculty, academic careers almost always ended at or before the age of 70. Only a handful of faculty members continued working longer, generally through special arrangements that exempted them from the mandatory retirement rule. Under the amended law, tenured professors’ lifetime appointments thenceforth permitted them to work as long as they wished, making when they retired into a matter of personal choice rather than of university policy.

The change created new challenges for both institutions and individuals. Universities now had to navigate the potentially sensitive process of separating long-serving faculty members from the academic careers they had pursued for a lifetime. Professors now had to decide when to stop doing the work that shaped their lives and, for many, Edie Goldenberg noted, defined their identities.

Twenty years after the new law, these issues have increasing salience on campuses across the country, because the cohorts that are nearing or have reached beyond the traditional retirement age represent an increasing proportion of the academic population. Between fall 1992 and 1998, the percentage of departures by full-time faculty because of retirement declined, at “almost every type of institution,” said Valerie Martin Conley. Continuing to work into their seventies became more commonplace. At the University of California-Berkeley, for example, “between 2002-3 and 2013, several faculty members have separated from the university as late as age 83,” Marc Goulden said.

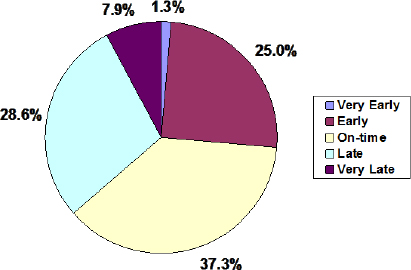

Universities are now seeing a “wide diversity of retirement and retirees,” a trend that will only grow, Martin Conley said. According to one study, the average age at which faculty members expect to retire is 66.5; for those still working at or past 71, however, the expected age is 75.7. Those figures, however, hide a great deal of variation. According to the 2003-4 National Study

of Postsecondary Faculty survey (see Figure 5-1), a plurality—37.3 percent—plan to retire “on time,” presumably in their mid- to late sixties. The next largest group, 28.6 percent, says they will retire “late,” and a slightly smaller share, 25 percent, intends to do so “early.” Almost 8 percent, however, say they will work until “very late,” and a tiny sliver, 1.3 percent, intends to leave “very early.”

More recently, a 2011 study of full-time faculty members over age 60 found fully three-quarters expecting to continue working past the customary retirement age, with 60 percent saying they would do so by choice and 15 percent citing external factors, which were “primarily financial” according to Martin Conley.8 Because these data were collected shortly after the 2008 economic collapse, however, many people’s retirement accounts may have since rebounded, she added.

Figure 5-1 Percentage distribution of expected timing of retirement of full-time instructional faculty and staff: 2003–04.

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, National Study of Postsecondary Faculty (NSOPF), Data Analysis System (DAS).

_____________________

8 Paul J. Yakoboski. “Should I Stay or Should I Go? The Faculty Retirement Decision.” Trends and Issues, TIAA-CREF Institute (December 2011).

“Almost all eligible full-time faculty members participate in employer-sponsored retirement plans,” and most institutions require them to do so, Martin Conley said. The financial arrangements offered in the plans of various universities, however, are “all over the map,” she says. The influence of the stock market on professors’ retirement intentions derives in large part from the growing importance of defined contribution plans, under which the employer and employee make set payments into the plan during the person’s working life, and payout then depends on the amount of money that has accumulated in the individual’s account, which in turn depends on economic conditions and investment strategy. Many public institutions and older private plans, however, offer defined benefits and pay out set amounts determined by such factors as salary and length of service, she explained.

For both the institution and the individual, however, the financial circumstances of potential retirees is only one of many complex issues that complicate the retirement pictures. From the standpoint of university administrators, “the availability of a tenured faculty position essentially as long as you want to hold it, puts institutions in a position where they may or may not be able to make decisions about human resources that private industry has a bit more flexibility to make,” Martin Conley said. Several participants wondered whether, for example, well-paid older professors who keep their positions past the traditional retirement age tie up funds that could be used to open tenure-track slots for less expensive younger faculty members.

“Theoretically, [more retirements] would open up positions,” Donna Ginther said. In practice, however, universities “are not hiring tenure-track faculty” and are using more and more adjuncts for teaching and soft-money staff scientists or associates for research. In the sciences, noted Committee on Science, Engineering, and Public Policy (COSEPUP) member Linda Abriola, salaries are only a small part of the cost of hiring new tenure-track faculty, with start-up packages and what R. Michael Tanner, vice president and chief academic officer at the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities, calls “the ever increasing race to give more and more start-up funds to the young stars,” a much more significant constraint.

In her 10 years as dean of engineering at Tufts University, said Abriola, she has seen the size of start-up packages rise sharply. “I used to budget $300,000 per start-up package. I am now budgeting $800,000 to a million dollars…” For that reason, “it is not economical for us to bring in too many junior faculty in any given year… . We actually can’t afford to have our faculty retire.” With about 20 percent of her faculty nearing or at retirement age, “if they all retired at once, we wouldn’t be able to teach our classes, and we would be forced to hire part-time faculty.”

On the other hand, retirements do tend to move universities toward another important goal, that of diversifying their faculties by race and gender. Younger faculty cohorts are much more diverse than their elders. At the University of California-Berkeley, for example, according to data provided by Goulden, men

comprise more than 75 percent of the professors over 70 years of age, but fewer than half of those under 30. Arriving at Princeton in 1978, Joan Girgus recalled, “I was the eighth tenured woman.” She also remembered hearing someone say at a meeting that “the best diversity plan a university can have is a good retirement program.”

Institutions that wish to encourage faculty to retire for whatever reason face significant challenges, however, especially making sure that the incentives they use comport with the law. “Two main points of friction [exist] between the legal system and faculty retirement,” said attorney Ann Franke, president of Wise Results, LLC, and author of a paper on legal issues regarding retirement for the American Council on Education. One is “whether people are leaving voluntarily or involuntarily” and the other is that “when money is changing hands between an institution and an individual,…there [are] tax consequences or consequences under the nation’s pension laws.” Institutions must design retirement policies to avoid the reality or even the appearance of coercion or favoritism. They must also examine the goals they wish their retirement policies to meet, design incentives that meet those goals, avoid any disincentives that detract from meeting those goals, and measure their policies’ results, she added.

Administrators, including department chairs and deans, must therefore avoid missteps such as stereotyping older faculty or singling out individuals for “targeted discussions of retirement,” Franke warned. Learning to avoid such pitfalls may require training in retirement law and proper practices, she said. “Vocabulary missteps,” for example, are a major potential snare, as in the case of “a dean of faculty who was advocating to the board of trustees a need for a retirement incentive program,” she continued. “His words made it into the Wall Street Journal. Here was his argument: ‘It is no secret that faculty effectiveness decreases with age and turnover would be healthy. Older faculty members become distanced from the modern roots of their fields.’ “ His talk described “the yellowed lecture notes, the less-traveled path to conferences and seminars, the less than enthusiastic welcome for students,” all of which, Franke said, are “ageist stereotypes.”

Administrators are therefore on “thin ice” asking individuals when they plan to retire, she added. “Some lawyers…say you can never ask when people are going to retire.” In her view, it is permissible “if you ask everyone in a department, if you ask them in writing, so that the message is consistent. You ask them to put down an age, their name, and you put on the piece of paper that we will not bind you to this. We are doing this for our planning purposes. Then, in my opinion, you are not violating the Age Discrimination in Employment Act.”

Another challenge is designing incentives that can motivate so varied and independent-minded a group of individuals. One obvious incentive is money, and the University of California had some success in the 1990s by offering a

series of very large incentives, known as the Voluntary Early Retirement Incentive Programs, Goulden said. Princeton is also endeavoring to “incentivize the tenured faculty through bonuses [based on age] to embrace 65 to 70 as an appropriate retirement age,” Girgus said. Those who sign an agreement to retire between 65 and 70 become eligible for a one-time bonus of 1.5 times their salary or 1.5 times the average salary of everyone at their rank, whichever is greater.

Princeton has what Girgus calls “a very strong merit salary system,” so salaries at each rank vary substantially. Acceptance of the bonus system has been especially high among “those who received a bonus based on the average salary at their rank,” she noted. “If you happen to be at the bottom of the salary distribution, the bonus you get is a lot higher than your salary would ordinarily suggest… . It is safe to make the inference that those [receiving the bonus based on the average for their rank] are the faculty that we have judged to be less productive.”

Money, however, does not reliably motivate all professors. More than 200 at Berkeley choose to “actually lose income” rather than retire, Goulden says. “Not even taking into account all the private accounts they might have, [counting] just Social Security [and] UC pension,” these individuals are losing “$20,000, $30,000, $40,000 [per year] they would get if they were to retire,” and one or two “as much as nearly $60,000… . This isn’t working for free. They are paying.”

This probably happens because work plays a much larger role in the lives of many academics than it does for nonacademic workers, Goulden continued. Only 28 percent of the American workforce says they derive their main satisfaction in life from their work, as opposed to 67 percent of the Berkeley faculty, according to data that he presented. For faculty members aged 65 or older, that percentage rises to 77 percent. One indication of this devotion to work is the long hours that faculty at Berkeley and, presumably, elsewhere put in across their working lives. The average workweek tops 50 hours until faculty members reach age 58, when it dips below that figure for the first time. Not until age 68 does it drop down to “the standard workweek [of] 40 hours,” Goulden says.

In fact, the desire to remain connected to the university, the academic community, and the life of the mind that had been their focus for decades can serve as a strong incentive for faculty members to continue working. “I think for many faculty the inhibition to retire is the fear of becoming irrelevant, disconnected, discarded, and forgotten,” Tanner said. “The key message that all institutions can do, and not necessarily at great expense, is to say, no, we still value what you have to offer. We want you to be connected. We want to draw on your expertise.”

In speaking with senior faculty nearing retirement, interviewers found that

many “felt marginalized,” said Claire Van Ummersen, senior advisor to the Institutional Leadership Group of the American Council on Education. “They wanted very much to be respected by their institutions, recognized for their contributions, and they were looking for ways to stay connected to the institution that would allow them to be intellectually engaged and have the sense that they were making a difference for that university. These were the most important things that faculty talked about to us.”

As an example, John Tully mentioned the story of Nobel laureate John Fenn, who so wanted to remain at work that “he applied for a junior faculty position at his old department.” Tully explained that Fenn “had to retire at 70 in 1992 or 1993.” After losing out to a younger applicant for the job, “he was threatening…a lawsuit, because he felt that his credentials were every bit as good as the person they hired. Now, that is not as frivolous as it sounds… . He didn’t really want a faculty position. He just wanted to be involved in the university.”

For this reason, some institutions have developed retirement programs that try to make the separation from regular faculty status gradual, but the connection to the university permanent. One approach growing in popularity is phased retirement, which generally allows faculty members to cut back their work responsibilities gradually, usually over a period of 3 to 5 years. “Touted as a major win-win,” this approach has “extended the time that faculty could pay into Social Security,… and shortened the time of complete dependence on retirement savings for income,” Martin Conley says. An American Association of University Professors survey done in 2007 showed a rapid increase in such programs, she said. In a survey of 3,300 senior faculty members nearing retirement, 75 percent of respondents preferred phased retirement, Van Ummersen added. At most institutions, individuals phasing out of their careers have left after the third year, even if the agreement allows for 5 years.

Also popular with faculty are retirement systems that have clear guidelines that apply to everyone and are openly discussed and readily accessible. Some institutions negotiate retirement arrangements privately with each individual. Faculty strongly dislike such arrangements, however, because they “didn’t know what the rules were,” Van Ummersen said. “They didn’t know what they could ask for” and feared that others had gotten a better deal. Having very clear policies and guidelines and making the information public clears up this problem.

Many faculty members also wish to continue their scholarly work after retirement, a desire often recognized by emeritus status. They “care deeply, as they are thinking toward retirement, about completing projects that they may be in the middle of,” Van Ummersen said. “Am I going to be able to get this finished before I leave? It is that last book that they want to write or some very important research that they want to finish. Anything that the institution can do to help them to do that” will ease the transition, she said.

Princeton, for example, provides emeritus faculty continued access to e-

mail addresses, computing privileges, library access, parking permits, and when possible, office space and secretarial and computer support. Those engaged in research may be named senior scholars, with continuing access to research accounts and the ability to accept new postdoctoral fellows (but not graduate students) and apply for certain special grants. On the other hand, City University of New York (CUNY), a very large public institution, doesn’t “have any money for the retired professoriate,” said Manfred Philipp, the former chair of the University Faculty Senate, the current president of CUNY Academy for the Humanities and Sciences, and a professor of chemistry at Lehman College. “The administrators don’t even want to give them e-mail, let alone an office.” The faculty union is pressing for the right to retain a university e-mail address after retirement. They are important not only to aid the retirees, he said, but because “retirees still do things like write letters of recommendation for students that they had while they were on the active faculty. They need to have these connections in order to provide these services to students.”

Office space for retired faculty is a “real problem,” Girgus said, “and lab space, even more. For those faculty that have grants, we try to provide lab space. For those who want offices, we try to provide office space or lockable carrels in the library.” Many workshop participants concurred that providing office space for retirees is an often insuperable challenge. COSEPUP member Gordon England suggested that facilities modeled on commercial business centers might meet the needs of some retirees.

An additional approach to keeping faculty connected and active are facilities for retired faculty, either associations or full-fledged emeriti centers. The emeriti center at the University of Southern California (USC), for example, was organized in 1978 at the request of an association that retired faculty had organized in 1949. Despite its name, the center is open to all retired faculty regardless of whether they have the emeritus designation. This “collegial body…does a lot of interesting things,” including educational and service projects and social events, said Janette Brown.

The USC center is one of the entities that belong to the Association of Retirement Organizations in Higher Education (AROHE), “a very small nonprofit” without a paid staff that is run as “a labor of love,” Brown continued. “Our [AROHE ] colleagues are composed of mostly retired faculty, but also leaders on college campuses,” she added. “Some of them are from the provost office. Some of them are from HR [human resources], some from benefits, some from the alumni association.”

A 2012 survey conducted by AROHE received 117 responses from across the United States and Canada, 75 of them from retiree associations rather than centers. Many institutions lack retiree centers or associations, and those that exist go under many different names, sometimes without a website. The overwhelming majority have fulfillment for retirees as their primary purpose, but many do service or teaching at the university or in the community, and some help prepare faculty members for retirement. They also afford members

privileges that can include use of the institution’s libraries and e-mail service, use of a university identification card, reduced fees for parking and events on campus, use of the institution’s computers, bookstore discounts, and in some cases, use of offices and more.

Keeping retired faculty connected to the life of the university has important advantages for the institution as well as for individuals, the group agreed. “Your retired faculty and staff, as a body, as a group, are the largest untapped resource that your college or university has,” said Brown. Sometimes those advantages can be extremely concrete, noted Philipp, who cited the example of chemist Alan Katrizky, a chemistry professor still active at age 84, who pledged $1.5 million to endow a chair in his field at the University of Florida. In 1980, Katrizky had moved to the Gainesville institution from the University of East Anglia in his native United Kingdom, where he had spent decades as a professor and dean, in order to avoid mandatory retirement at age 65.

Some of what Philipp called the “distinctive assets” of retired faculty are more intangible, but still important. “Strategically engag[ing] vigorous retired professors…can help college[s] and universities maintain a reserve pool of flexible and readily available faculty resources to help institutions adapt to rapidly changing program needs in a time of fiscal constraint.” He cited as an example Edward Gerjuoy, an emeritus professor of astronomy and physics at the University of Pittsburgh, who in his mid-90s continues to work in his office 6 hours a day, often including weekends, to write papers, and to do voluntary service for the American Physical Society.

Universities “get so much value out of keeping their former faculty involved,” Tanner added. “Many of the former faculty still have a lot of influence externally. They are still working to get awards for their current faculty and writing letters of recommendation and just the wisdom that they can give to the institution. That should be a responsibility of the institution and it will pay off for them.”

Fashioning policies that assist faculty in making appropriate choices about when and how to retire, the group agreed, redound to the welfare not only of the individual professors but also of the institution as a whole. “Retirement choice…was, of course, one of the major tenets behind the spirit of the Age Discrimination in Employment Act and the elimination of mandatory retirement,” Martin Conley said. “We do still need to think about retirement as a choice, and make sure that we have policies and programs in place that are allowing people to work longer because they want to, rather than to work longer because they have to.…What is at stake is nothing short of the quality of life for the academic workforce and their prospects for a comfortable retirement, or perhaps even the ability to retire at all, and in turn, the learning environment for our students.”