A Examples of Clinical Practice Guidelines and Related Materials1

This appendix, which is a collection of clinical practice guidelines and related materials,2 has three main purposes. First, for readers not familiar with guidelines, it presents samples that may make the text of this report more concrete. Second, it illustrates how guidelines can differ. Third, the appendix discusses the topic of formatting, which is in some ways a step between development and implementation.

Apart from the sponsoring agency or organization, guidelines can vary (as noted in Chapter 1) in at least five key ways:

-

Clinical orientation—whether the chief focus is a clinical condition, a technology (broadly defined), or a process.

-

Clinical purpose—whether they advise about screening and prevention, evaluation or diagnosis, aspects of treatment, or other dimensions, or more discrete aspects of health care.

-

Complexity—whether the guidelines are relatively straightforward in presentation and discussion or are marked by considerable detail, complicated logic, or lengthy narrative and documentation. For purposes of the descriptions in this appendix, complexity is indicated simply as high, medium, or low.

-

Format—whether the guidelines are formatted as free text, tables, if-then statements, critical pathways, decision paths, or algorithms.

-

Intended users—whether they are intended for practitioners, patients, or others.

The next section of this appendix discusses the ways guidelines may be formatted. The rest of the appendix presents, in whole or in part, 16 guidelines and related items (see Table A-1). Each example is preceded by an annotation indicating the principal information for the five variables just noted. In addition, a brief introduction highlights especially salient points about the item in terms of purpose, content, or presentation. These notes should in no way be considered a complete analysis or evaluation of the item in the example. At the end of each write-up is the complete reference or citation to the guideline.

Inclusion in this appendix does not imply endorsement of the content of these guidelines or of the process by which they were developed. Some of these materials are not, for example, the products of a systematic develop

TABLE A-1 List of Examples, by Main Purpose

|

Screening and Prevention 1. Screening for diminished visual acuity in children 2. Vaccination for pregnant women who are planning international travel |

|

Diagnosis and Pre-Diagnosis Management of Patients 3. Triage of the injured patient 4. Evaluating chest pain in the emergency room 5. Using erythrocyte sedimentation rate tests in diagnosis |

|

Indications for Use of Surgical Procedures 6. Indications for carotid endarterectomy 7. Indications for percutaneous transluminal coronary angiography 8. Managing labor and delivery after previous cesarean section |

|

Appropriate Use of Specific Technologies and Tests as Part of Clinical Care 9. Using autologous or donor blood for transfusions 10. Detecting or tracking deteriorating metabolic acidosis |

|

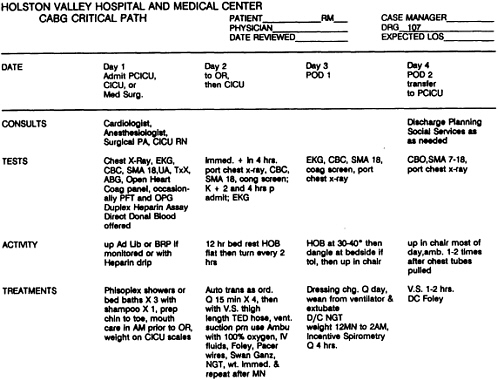

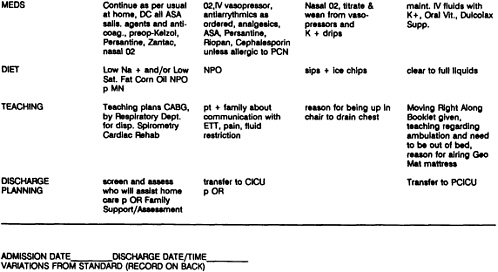

Guidelines for Care of Clinical Conditions 11. Using oral contraceptives to prevent pregnancy and manage fertility 12. Deciding on treatment for low back pain 13. Managing patients following coronary artery bypass graft 14. Guidelines for the management of patients with psoriasis 15. Acute dysuria in the adult female 16. Management of acute pain |

ment process. Others may result from such a procedure but do not include references to the scientific literature used in development.

FORMATTING GUIDELINES

Formatting is a step beyond the development of a guideline. It can be executed in many ways and at many stages in the process of moving guidelines from development to application. Congress, for instance, recognized the importance of formatting by requiring the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) to present its guidelines in formats that are appropriate for use by practitioners, medical educators, and medical care reviewers.

Many formatting activities of most relevance to the persuasive and effective presentation of guidelines may occur after the initial formatting and dissemination of a set of guidelines by its sponsor or developer. For example, a professional society may initially present its guidelines in one format in a journal but then rework them into another format for use in continuing medical education. The initial guidelines may also be converted by target users--—hospitals, clinics, utilization review firms, health maintenance organizations, patient groups, and others—into formats ranging from a sophisticated computer-based algorithm to a simple chart that the patient can put on the refrigerator door or bathroom mirror. Voluntary associations such as the American Cancer Society and American Heart Association, as well as commercial firms, may reformat guidelines in various ways for dissemination to different groups.

Guidelines can vary quite dramatically, both logically and graphically, in their modes of presentation. The major approaches are free-text and formalized presentations, including if-then statements, algorithms, flowcharts, and decision trees. More recently, some clinical researchers and medical informatics experts are moving to more complex computer-based approaches. These approaches are discussed briefly below.

Free Text

The most common format for guidelines is free text; this report, for example, is presented in free text. Generally, free text is the starting point for most other formats and itself has many variants.

Shortened free-text versions of guidelines documents can be tailored for specific uses by specific types of practitioners. For instance, guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute myocardial infarction might well be rendered into several different versions and formats depending on whether the target audience was to be emergency room physicians needing quick reference or cardiac specialists managing a patient over several weeks.

Narrative information may be collapsed into tables or graphs or summarized in highly technical terms with liberal use of acronyms, abbreviations, or symbols.3

To cite one example of a series of formatting steps, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force took its guidelines to a commercial publisher, which created and copyrighted the graphic design and produced the guidelines for general publication. In addition to the basic text, that publication includes eight small, plasticized pull-out charts summarizing screening, counseling, and immunization schedules for different patient age groups. These tables include abbreviated references to nonroutine situations for which physicians may consider deviations from the schedules.

Guidelines can also be rendered into much simpler, less technical documents for use by patients, consumers, and their families. Although the free-text approach is likely to be preserved, some use may be made of lay terms (including colloquialisms), simple drawings, and such heuristic devices as introductory questions. One would expect such versions of guidelines to differ, depending on the target audience.

Formalized Presentations

Apart from translations into shorter, simpler, nontechnical versions, which may still be in a free-text format, guidelines documents may be formatted into stylized graphic representations such as flowcharts or decision trees. These, in turn, may become programs for computer-based clinical decision making tools.

One reason for translating free text into other formats is that some guidelines identify dozens, if not hundreds, of specific criteria for care; even creative free-text presentations may not allow practical, quick access to this volume of information. Instead, the free text may be reconfigured (or, less often, the initial guidelines may be drafted) using various related or overlapping formal approaches including flowcharts, decision tables, and if-then rules.

Algorithms

Typically, a preliminary step in the development of many such formats is the development of a clinical algorithm. Algorithms were invented in the ninth century by a Persian mathematician, Al-khaforizmi, to solve arithmetic problems. They were first applied to practical problem solving by the U.S. Army in job-training manuals, and they have been fundamental to the programming of electronic computers. More specifically in the health field, algorithms have been used since at least the 1960s to aid clinical problem solving (Gottlieb, 1990).

Strictly speaking, an algorithm is not a graphic representation but rather a presentation of information for decision making using step-by-step conditional logic rather than ordinary prose or lists of factors to be considered. This distinction is frequently ignored.

The clinical algorithm, even when not used as the format of choice for disseminating guidelines, may be used to compare guidelines and to identify missing or conflicting decision "branches." In developing methods for analyzing and comparing guidelines, Margolis et al. (1991) have identified categories of logical error in guideline construction and have described the complexity of different guidelines in quantitative terms. Applying such a process could lead to the significant reworking of a set of guidelines, not just a repackaging or interpretation of the same content.

Constructing algorithms and translating them into flowsheets and other tools can be a powerful learning process for practitioners. The process can (1) highlight differences in practice patterns and values that may need to be explored, (2) clarify key characteristics and weaknesses of processes of care, (3) identify gaps in clinical knowledge, and (4) contribute to redesign of systems of care.

Free-text versions of guidelines or review criteria usually precede the development of algorithms and similar formats, but one exception is worth noting. The Health Standards and Quality Bureau of the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) is developing quality-of-care and appropriateness algorithms for collecting and analyzing clinical data in its Uniform Clinical Data Set (UCDS; Krakauer, 1990; Krakauer and Bailey, 1991). The agency believes that the application of these computer-based algorithms will be a major tool for quality review for the Medicare peer review organizations (PROs), improving on the manual review of hospital charts by PRO nurse reviewers.

The UCDS development process began in the late 1980s with more than 3,000 complex software algorithms for direct collection of data and identification of hospital admissions that did not meet certain admission or quality-of-care criteria. However, little documentation of the programming or clinical logic was performed. Consequently, the procedures and rules against

which practitioners and hospitals may be judged to have provided poor or unnecessary care cannot be easily explained to clinicians or institutions. HCFA has sponsored some work to prepare free-text versions of the fraction of these algorithms that can generate "flags" about potential quality-of-care deficiencies.

Flowcharts and Similar Formats

Graphic representations of algorithms are of various kinds. They include flowcharts, decision tables (sometimes used to indicate appropriate health screening), protocol charts (e.g., for handling medical problems by telephone), and so-called influence diagrams (a decision clarification tool imported from the business world and now being adapted to medicine).

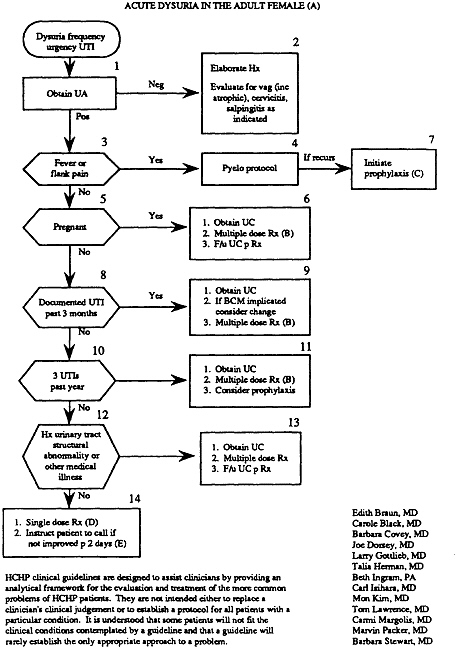

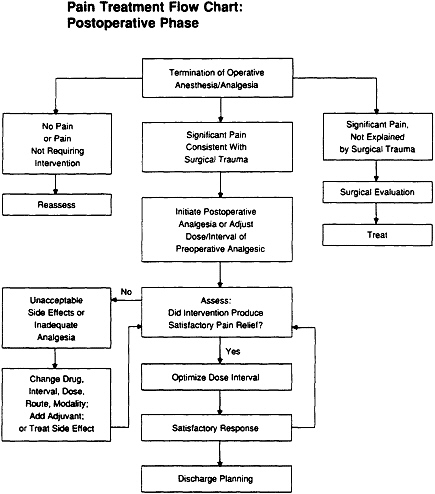

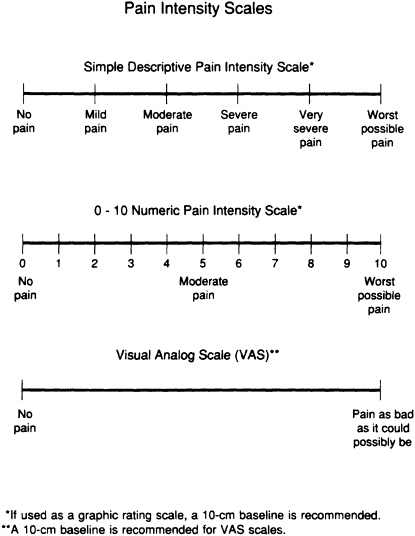

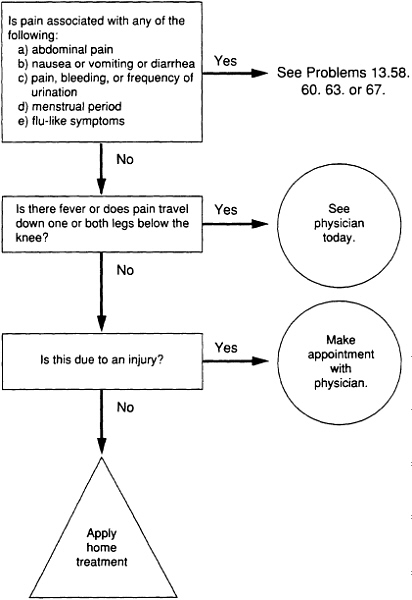

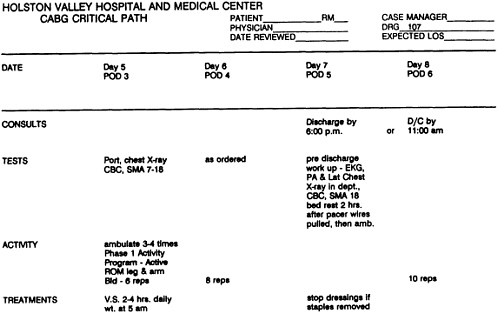

As used to assist clinical problem solving, flowcharts (which are commonly called algorithms) begin with a clinical condition or patient symptom and lead the reader through a series of branching, dichotomous choices based on the patient's risk status, medical history, or clinical findings. They also include action steps such as testing, treating, or scheduling further examinations. This appendix presents two flowcharts, one for patients (Example 12 on the treatment of low back pain) and one for practitioners (Example 15 on the treatment of dysuria). In clinical practice, flowcharts may help practitioners choose from among alternative actions the most efficient sequence (as in a diagnostic workup); they may also aid in reducing the likelihood of overlooking uncommon but important elements of care for specific patients.

The basic elements of flowcharts include boxes and arrows; the latter connect the boxes or direct the user to other parts of the algorithm. The boxes may be numbered and have internal text, and they may come in several shapes, depending on whether they describe a clinical state, ask a question (diagnostic assessment), or describe an action to be taken. Prose may be used to annotate the boxes. Experts recommend that flowcharts read from left to right and top to bottom and that only two arrows exit from a given box, corresponding to a yes or no response to the clinical question posed. (Further rules for creating flowcharts and algorithms are proposed below.)

Practitioners differ widely in their attitude toward flowcharts, decision trees, and other shorthand, visual formats for guidelines. Some see them as helpful reminders and a useful tool for assimilating or quickly locating information. Others are emphatic in their dislike of these formats, maintaining that the sequences do not represent the experienced clinician's mental processes or that the necessary complexity makes them impractical to use during care of a patient. Alternatively, they may argue that simplified formats do not adequately account for all the factors present in patient care.

Some practitioners are concerned that algorithms make patient care appear cut and dried and that they will become a series of rules to be applied, with mindless rigidity, by those without clinical expertise. As can happen with any format, some physicians may view any guidelines for familiar clinical conditions as insults that imply that without such a guideline they would not know what care to provide.

Proposed Standards

As noted, the clinical algorithm map, a type of practice guideline, has received increased attention in recent years and appears more frequently in various medical journals. However, format, style, graphics, and uses vary widely, posing an obstacle to widespread use and dissemination. To overcome this difficulty, Margolis, Gottlieb, and their associates (Margolis et al., 1991) advanced some suggestions for standardization of algorithms, which are briefly presented here. The proposals involve use of boxes, including clinical state boxes, decision boxes, action boxes, and link boxes; arrows; a numbering scheme; pagination; abbreviations; and various aspects of annotations.

TITLE

The title should define the clinical topic and intended users. Under it, the authors, their degrees, and institutional affiliations should be listed. The date of publication and revision (if applicable) should be specified. A footnote to the title should state the process by which the algorithm logic was decided; this might be, for instance, group consensus after literature review, individual recommendation based on clinical experience, or some other technique.

BOXES

Clinical state box—rounded rectangle or elliptical box. This box defines the clinical state or problem. It has only one exit path and may or may not have an entry path. This box always appears at the beginning of an algorithm. The initial clinical state box should describe the clinical problem to be addressed. Clinical state boxes in the body of the algorithm are used to clarify the status of the patient or diagnosis along the path of the algorithm (i.e., to describe a subset of patients with a particular clinical condition).

Decision box—hexagon. This box requires a branching decision, whose response will lead to one of two alternative paths. It always has an entry path and two exit paths. Statements in decision boxes should be phrased as questions punctuated with question marks. If two assessments are to be determined, then the developers should specify whether both (''and") or one

("or") must be positive for a "yes" response. Multiple questions can be asked in one box, and criteria are specified for a "yes" response to the entire box—for instance, whether two of three criteria must be present, whether all must be present, or whether any must be present.

Action box—rectangle. This box indicates an action, commonly either therapeutic or diagnostic. Several rules are suggested for action boxes, as follows: A single phrase within a box should not be punctuated with a period. Multiple actions that do not need to be sequenced in time may be listed in one box. When multiple actions are presented in one box, each action is to be listed on a separate line (preceded with an optional number, dash, or bullet). When two statements are to be joined by "and" or "or," the conjunction should be placed on a separate line for emphasis.

Link box—small oval. This box is used in place of an arrow, to link boxes for graphic clarity. This might be useful at page breaks or between separated nodes to maintain path continuity. The box itself should read "Go to Page ... Box ...."

ARROWS

Several rules for arrows have also been advanced. The flow should be from top to bottom. In general, the flow should be from left to right, except when a side branch rejoins the main stem. Arrows should never intersect. Link boxes (see above) can be used to avoid crossing paths. Arrows originating from decision boxes should be labelled "yes" or "no." No other text should be used over an arrow. Wherever possible (i.e., where clinical content will not be obscured), "yes" arrows should point to the right, and "no" arrows should point down.

NUMBERING SCHEME

Clinical state boxes, decision boxes, and action boxes should be numbered sequentially from left to right and from top to bottom. Link boxes are not numbered.

PAGING

Whenever possible, it is advisable to consolidate the algorithm so that it can be presented on one page. Page breaks are inserted where clinical logic indicates, and a single box should not be isolated on a page. For complex algorithms, the first page could best serve as a directory to clinical subsets of patients. In this case, each subset is identified as a clinical state box.

ANNOTATIONS

Citation of the annotation. Annotations are an intrinsic part of the algorithm. They are used to clarify the rationale of the decisions, cite the supporting literature, and expand on less essential details of the clinical

information contained in the box. Annotations would be cited following a single phrase using a capital letter at the end of the phrase. When multiple statements are contained in a single box, annotation(s) should appear at the end of the phrase(s) to which it is applicable. If an annotation is applicable to the entire box with multiple statements, then it should be cited using a capital letter centered on a separate line at the bottom of the box.

Annotation format. Annotations should be written in text format and should appear on pages that are separate from the algorithm. They should be referenced according to standard medical reference format, with references numbered using superscripts within the text.

ABBREVIATIONS

Except for units of measurement, abbreviations are discouraged.

Computer-based Formats

Some clinical researchers argue that clinical flowcharts are inefficient representations of algorithms because they are limited by yes/no branch points to arbitrary sequences and thus cannot accommodate the richer choices common to medicine. They have been looking for ways to avoid flowcharts and to move toward a "meta-language" by using a standard syntax to convert algorithms to different kinds of computer-based decision aids. The Arden Syntax, developed in medical centers with private-sector support, is an effort to create such a system (McDonald et al., 1991; Megargle, 1991).

Using this syntax, a well-defined algorithm can be transformed into various kinds of computer programming statements such as if-then statements or for-loop statements. Use of the Arden Syntax allows easy transfer of understandable contraindication alerts, management suggestions, data interpretations, treatment protocols, and similar aids from one computer system to another. Example 10, on detecting deteriorating metabolic acidosis, and Example 11, on the use of oral contraceptives, illustrate specific computer-based formats.

The rest of the appendix presents 16 examples of guidelines and related materials. A range of topics, formats, sponsors and users, clinical orientations and purposes, and levels of complexity are presented and discussed; cross-comparisons within the appendix are noted. As stated above, these discussions should not be taken as complete analyses of the items in question, nor should inclusion in this appendix be taken as endorsement of the content or development process of these guidelines.

Example 1

SCREENING FOR DIMINISHED VISUAL ACUITY

|

Clinical orientation: |

Clinical condition |

|

Clinical purpose: |

Screening and prevention |

|

Complexity: |

Medium |

|

Format: |

Free text and a stand-alone reference chart |

|

Intended users: |

Practitioners, perhaps patients |

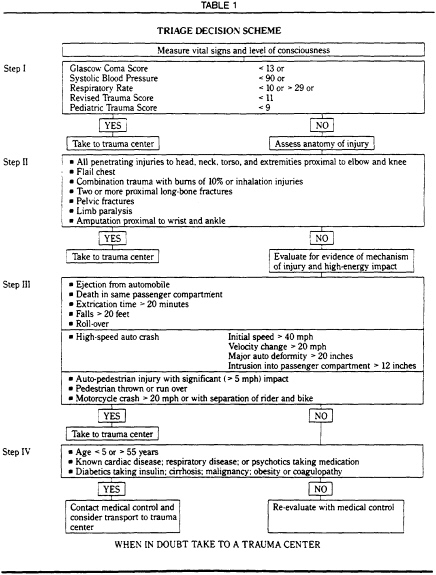

In 1989, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) published a 419-page document intended mainly for primary care providers. The task force's objective was to develop comprehensive recommendations addressing preventive services for all age groups for 60 target conditions, using a systematic process and explicit criteria to review evidence and develop recommendations. The work of the task force was discussed extensively in Chapter 2 and elsewhere in the report.

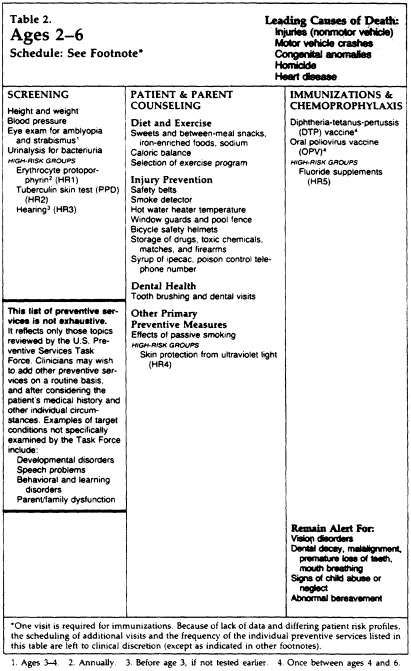

This particular guideline is presented, in the USPSTF book, as part of a larger course of preventive care. It is one of 169 guidelines for specific preventive interventions, each of which may include recommendations for preventive care by age group (e.g., in favor of vision screening for children of younger ages and possibly for the elderly but not for adolescents and adults). Reproduced here are (1) the specific recommendations for vision screening and (2) the plasticized reference card for preventive care of children ages 2-6, which recommends vision screening.

In its concern with reliability of a particular test, this guideline is similar to the one on erythrocyte sedimentation rate tests (Example 5). As is true of several items in the appendix, this guideline cites the literature on which it is based. Educated patients might also make use of this guideline, as they could for the guidelines on, for instance, deciding what to do about low back pain or managing labor and delivery after a previous cesarean delivery (see Examples 12 and 8, respectively).

SOURCE: Reprinted (public domain) from: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services: An Assessment of the Effectiveness of 169 Interventions. Baltimore, Md.: Williams & Wilkins, 1989.

Screening for Diminished Visual Acuity

Recommendation: Vision screening is recommended for all children once before entering school, preferably at age 3 or 4 (see Clinical Intervention). Routine vision testing is not recommended as a component of the periodic health examination of asymptomatic schoolchildren. Clinicians should be alert for signs of ocular misalignment when examining all infants and children. Vision screening of adolescents and adults is not recommended, but it may be appropriate in the elderly. Screening for glaucoma is discussed in Chapter 32.

Burden of Suffering

About 2-5% of American children suffer from amblyopia ("lazy eye") and strabismus (ocular misalignment), and nearly 20% have simple refractive errors by age 16.1-4 Amblyopia and strabismus usually develop between infancy and ages 5-7.3 Since normal vision from birth is necessary for proper eye development, failure to treat amblyopia and strabismus before school age may later result in irreversible visual deficits, permanent amblyopia, loss of depth perception and binocularity, cosmetic defects, and educational and occupational restrictions.1,4,5 In contrast, refractive errors such as myopia become common during school age but rarely carry serious prognostic implications.1,3,6,7 Experts disagree on whether uncorrected refractive errors cause diminished academic performance among schoolchildren. 1,3,5,7,8,

The majority of vision disorders occur in adults; over 8.5 million Americans suffer from visual impairment 9 Visual disorders such as presbyopia (decreased ability to focus on near objects) become more common with age10 and therefore the prevalence of visual impairment is highest in those over age 65. Preliminary statistics from recent surveys suggest that nearly 13% of Americans age 65 and older have some form of visual impairment, and almost 8% of this age group suffer from severe impairment: blindness in both eyes or inability to read newsprint even with glasses.11 Vision disorders in the elderly may be associated with injuries due to falls and motor vehicle accidents, diminished productivity, and loss of independence.12 Many older adults are unaware of changes in their visual acuity, and up to 25% of them may be using an incorrect lens prescription.12

Efficacy of Screening Tests

Although screening for strabismus and amblyopia is most critical at an early age, screening tests to detect occult vision disorders in children under age 3 have

generally been unsuccessful due to the child's inability to cooperate, the time required for testing, and the inaccuracy of the tests.13-15 Promising techniques such as alternate stimulation (cover testing), preferential-looking, grating acuity cards, and refractive screening are currently being developed for this age group.14,16,17 Although refractive errors detected during infancy can predict some cases of amblyopia and strabismus, the sensitivity of this form of screening is quite poor.2

Screening tests for detecting strabismus and amblyopia in preschool children over age 3 include simple inspection, visual acuity tests, and stereograms. Visual acuity tests include the Snellen eye chart, the Landolt C, the tumbling E, the Sheridan-Gardner STYCAR test, Allen picture cards, grating cards, and other techniques.15 The specificity of most acuity tests, however, is imperfect for detecting strabismus and amblyopia because diminished visual acuity can occur in other conditions, such as simple refractive error or visual immaturity. 2 In addition, many children with nonamblyopic strabismus often have normal visual acuity but are at risk for serious complications 2,18 Thus, although simple acuity tests are inexpensive and easy to administer, they may miss many cases. Snellen letters, for example, are estimated to have a sensitivity of only 25-37%.2,18,19 Refractive screening has also been criticized as not being a direct test for either amblyopia or strabismus.2

Stereograms such as the Random Dot E (RDE) have been proposed as more effective than visual acuity tests in detecting strabismus and amblyopia in preschool children.2,18,20,21 The test, in which the patient views test cards through Polaroid glasses, requires about one minute to perform.18,20 When compared with a battery of visual tests, the RDE has an estimated sensitivity of 64%, specificity of 90%, positive predictive value of 57%, and negative predictive value of 93%.18

A more effective but less efficient strategy is the combination of more than one visual test.2,19 The Modified Clinical Technique (MCT), for example, includes retinoscopy, cover and Hirschberg tests, the Snellen acuity test, a color vision test, and external observation of the eye. The MCT has gained acceptance among optometrists since its introduction in the Orinda Study of 1959.18,22-24 Sensitivity and specificity in excess of 90% were found in that study and have since been reproduced in screening programs involving as many as 50,000 children.18 The MCT cannot be used routinely by primary care physicians for screening purposes, however, because it requires about 12 minutes to perform and the examiner must be a skilled eye care specialist.18,23

Vision screening of older children and adults is a means of detecting unrecognized refractive errors. Tests of visual acuity are often used for this purpose, but few studies have examined the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value of these tests in adult age groups.

Effectiveness of Early Detection

There is convincing evidence that early detection and treatment of vision disorders in infants and young children improve the prognosis for normal eye development.21 A prospective study has demonstrated that preschool children who receive visual acuity screening have significantly less visual impairment than controls when reexamined 6-12 months later.25 Detection and treatment of strabismus and amblyopia by age 1-2 can increase the likelihood of developing normal or near-normal binocular vision and may improve fine motor skills.2,4 Interventions for amblyopia and strabismus are significantly less effective if started after age 5, and such a delay increases the risk of irreversible amblyopia, ocular misalignment, and other visual deficits.1,3 It is widely held that clinical screening tests can detect

these disorders earlier than parents or teachers; only about 50% of children with ocular misalignment have a cosmetically noticeable defect.2,8

There is little evidence that bilaterally equal refractive errors among older children and adolescents are associated with significant morbidity, such as diminished academic performance.1,3,6,7 This is true in young adults as well, and, in addition, uncorrected vision disorders are quite uncommon among young adults.26 Vision screening for older adults is defended on the grounds that the prevalence of abnormal visual acuity is considerably greater among the elderly10 and these deficits are more commonly left uncorrected.26 Among persons aged 65-74, a visual acuity of 20/50 or less has been measured in 11% of those who wear glasses and in 26% of those who do not.26 Some forms of visual impairment in the elderly are associated with difficulties in ambulation,27 and early correction of refractive errors may serve a role in preventing injuries and facilitating the performance of daily living functions. However, there have been no prospective studies documenting these benefits in an elderly cohort receiving vision screening.

Recommendations of Others

The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends an ophthalmological examination of newborns who are premature or at risk for eye disease; an examination of fixation preference and ocular alignment by age 6 months; an examination of visual acuity, ocular alignment, and ocular disease at age 3-4; annual screening of schoolchildren for visual acuity and ocular alignment; occasional examinations from puberty to age 40; and an examination for presbyopia at age 40 and every two to five years thereafter.1 The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends external examination and tests of following ability and the pupillary light reflex in the newborn period and once during the first six months.5 Testing of visual acuity, ocular alignment, and ocular disease is recommended by the Academy at ages 4, 5-6, and at less frequent intervals thereafter.5 The Canadian Task Force recommends an eye examination and cover test at ages 1 week, 2 months, and, along with a vision chart test, at age 2-3 years and 5-6 years. Testing at age 10-11 is considered discretionary, and no adult screening is recommended.28 The American Optometric Association recommends screening schoolchildren every three years and annual eye examinations in adults after age 35.29 Screening guidelines have also been issued by other organizations, such as the National Society to Prevent Blindness, the National Association of Vision Program Consultants, Volunteers for Vision, and the American Public Health Association.2,8 Vision screening of preschool and school children is also required by law in some states and in a number of Federal programs.2,22

Discussion

Although it is established that early detection of strabismus and amblyopia is most beneficial for children under age 3, a practical and effective screening test is not yet available for this age group. Clinicians should, of course, be alert to signs of ocular misalignment when examining infants and young children. Screening tests for preschool children are available but, with the exception of a comprehensive battery (e.g., the MCT), most tests for amblyopia and strabismus lack the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value that are expected of good screening tests. Of these, the Random Dot E stereogram appears to have the best performance and is recommended by many experts. 2,21 Due to the high rate of false-negative results with this test, however, it would need to be repeated throughout the preschool period to achieve optimal effectiveness.

Screening of schoolchildren by primary care clinicians is not recommended because the procedure is usually performed by the public school system, and there is little scientific evidence that early detection of myopia is of greater benefit than detection when symptoms first become apparent. Similarly, there is no basis for screening asymptomatic adolescents or adults below age 40 who lack specific risk factors for vision disorders. With increasing age, there is a stronger argument for the early detection of uncorrected visual impairment to help prevent injury and improve independent living. The performance characteristics of acuity tests at this age are poorly described, and the claimed benefits of screening have not been proved. Repeated acuity testing can, however, improve sensitivity with presumably little cost or inconvenience to the patient. There are no available data for any age group on the optimal interval for vision screening; recommended frequencies are selected arbitrarily on the basis of expert opinion.

Clinical Intervention

Testing for amblyopia and strabismus is recommended for all children once before entering school, preferably at age 3 or 4. Stereotesting (e.g., Random Dot E stereogram) is more effective than visual acuity testing (e.g., Snellen optotype cards) in detecting these conditions. Routine screening for refractive errors is not recommended as a component of the periodic health examination of asymptomatic schoolchildren. Clinicians should be alert for signs of ocular misalignment when examining all infants and children. Vision screening of asymptomatic adolescents and adults is not recommended. It may be appropriate in the elderly, but there is insufficient evidence to recommend an optimal interval. All patients with abnormal test results should be referred to an eye specialist for further evaluation. Screening for glaucoma is discussed in Chapter 32.

REFERENCES

1. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Infants and children's eye care. Statement by the American Academy of Ophthalmology to the Select Panel for the Promotion of Child Health, Department of Health and Human Services. San Francisco, Calif.: American Academy of Ophthalmology, 1980.

2. Ehrlich MI, Reinecke RD, Simons K. Preschool vision screening for amblyopia and strabismus: programs, methods, guidelines, 1983. Surv Ophthalmol 1983; 28:145-63.

3. Cross AW. Health screening in schools. Part I. J Pediatr 1985; 107:487-94.

4. Sanke RF. Amblyopia. Am Fam Physician 1988; 37:275-8.

5. American Academy of Pediatrics. Vision screening and eye examination in children. Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine. Pediatrics 1986; 77:918-9.

6. Rosner J, Rosner J. Comparison of visual characteristics in children with and without learning difficulties. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1987; 64:531-3.

7. Helveston EM, Weber JC, Miller K, et al. Visual function and academic performance. Am J Ophthalmol 1985; 99:346-55.

8. APHA resolution number 8203: children's vision screening. Am J Public Health 1983; 73:329.

9. National Center for Health Statistics. Prevalence of selected chronic conditions, United States, 1979-81. Vital and Health Statistics, series 10, no. 155. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1986. (Publication no. DHHS (PHS) 86-1583.)

10. Idem. Monocular visual acuity of persons 4-74 years, United States, 1971-1972. Vital and Health Statistics, series 11, no. 201G. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Health Statistics, 1977:60. (Publication no. DHEW (HRA) 77-1646.)

11. Nelson KA. Visual impairment among elderly Americans: statistics in transition. J Vis Impair Blind 1987; 81:331-4.

12. Stults BM. Preventive health care for the elderly. West J Med 1984; 141:832-45.

13. Hall SM, Pugh AG, Hall DMB. Vision screening in the under-5s. Br Med J 1982; 285: 1096-8.

14. Jenkins PL, Simon JW, Kandel GL, et al. A simple grating visual acuity test for impaired children. Am J Ophthalmol 1985; 99:652-8.

15. Fern KD, Manny RE. Visual acuity of the preschool child: a review. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1986; 63:319-45.

16. Jacobson SG, Mohindra I, Held R. Visual acuity of infants with ocular diseases. Am J Ophthalmol 1982; 93:198-209.

17. Brown AM, Yamamoto M. Visual acuity in newborn and preterm infants measured with grating acuity cards. Am J Ophthalmol 1986; 102:245-53.

18. Hammond RS, Schmidt PP. A Random Dot E stereogram for the vision screening of children. Arch Ophthalmol 1986; 104:54-60.

19. Lieberman S, Cohen AH, Stolzberg M, et al. Validation study of the New York State Optometric Association (NYSOA) vision screening battery. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1985; 62:165-8.

20. Simons K. A comparison of the Frisby, Random-Dot E, TNO, and Randot Circles stereotests in screening and office use. Arch Ophthalmol 1981; 99:446-52.

21. Reinecke RD. Screening 3-year-olds for visual problems: are we gaining or falling behind? Arch Ophthalmol 1986; 104:33.

22. Nussenblatt H. Symposium on optometry's obligation in vision screening. Opening remarks. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1984; 61:357-8.

23. Peters HB. The Orinda Study. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1984; 61:361-3.

24. Woodruff ME. Vision and refractive status among grade 1 children of the province of New Brunswick. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1986; 63:545-52.

25. Feldman W, Milner R, Sackett B, et al. Effects of preschool screening for vision and hearing on prevalence of vision and hearing problems 6-12 months later. Lancet 1980; 2:1014-6.

26. National Center for Health Statistics. Refraction status and motility defects of persons 4-74 years, United States, 1971-1972. Vital and Health Statistics, series 11, no. 206. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Health Statistics, 1978: 89-93. (Publication no. DHEW (PHS) 78-1654.)

27. Idem. Aging in the eighties, impaired senses for sound and light in persons age 65 and over. Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, no. 125. Hyattsville, Md.: National Center for Health Statistics, 1986:4-5. (Publication no. DHHS (PHS) 86-1250.)

28. Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. The periodic health examination. Can Med Assoc J 1979; 121:1194-254.

29. Miller SC, American Optometric Association. Personal communication, October 1988.

Example 2

VACCINATION FOR PREGNANT WOMEN

|

Clinical orientation: |

Clinical states (protection against certain disorders, in the context of pregnancy, an existing clinical condition); use of a technology (vaccination guidelines) |

|

Clinical purpose: |

Prevention, in the context of managing a clinical condition |

|

Complexity: |

Low |

|

Format: |

Free text; summary tables; maps (excerpts included) |

|

Intended users: |

Practitioners, perhaps patients |

This is an example of guideline development by a federal agency-here the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) of the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS)---as a direct product of its mandate. Example 1 on screening vision also came from a PHS agency and Example 9 on blood transfusions is the product of a state mandate. Chapter 2 discusses more fully the development of various guidelines at CDC and other federal agencies. Although aimed at clinicians, this guideline could be used by well-informed patients and consumers.

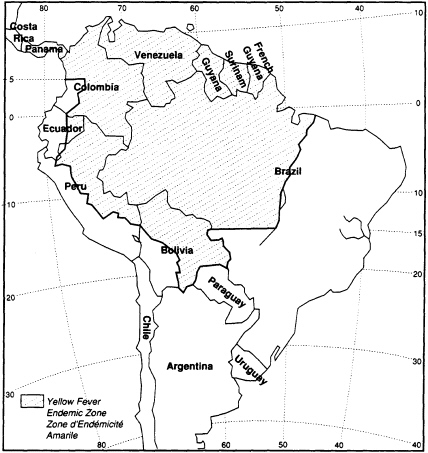

Of interest is the inclusion in the guideline of maps indicating areas in the world that are probably infected with specific diseases. An example concerning yellow fever in the Americas is included here. Since yellow fever vaccination is contraindicated except in cases of likely exposure, this map provides additional information for pregnant women to consider as they contemplate travel outside the United States. This guideline is the only one in the appendix to categorize levels of care according to ''sociogeographic" considerations (i.e., level of health, common health perils, or socioeconomic level of a particular locale)—a reflection of its concern with providing advice for international travel and with controlling the entry of infectious diseases into the United States.

Finally, this guideline was also included because it has two very different orientations: it can be seen as a guideline for a broadly defined technology (immunization) that includes information for the care of quite specific patients, or as a guideline combining two clinical states (pregnancy and potential exposure to disease) and providing recommendations on the intersecting territory.

SOURCE: Reprinted (public domain) from: Centers for Disease Control. Health Information for International Travel, 1990. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1990.

VACCINATION DURING PREGNANCY

On the grounds of a theoretical risk to the developing fetus, live, attenuated-virus vaccines are not generally given to pregnant women or to those likely to become pregnant within the next 3 months after receiving vaccine(s). With some of these vaccines—particularly rubella, measles, and mumps—pregnancy is a contraindication. Both yellow fever vaccine and OPV can be given to pregnant women at substantial risk of exposure to natural infection. When a vaccine is to be given during pregnancy, waiting until the second or third trimester is a reasonable precaution to minimize any concern over teratogenicity. Although there are theoretical risks, there has been no evidence of congenital rubella syndrome in infants born to susceptible mothers who inadvertently received rubella vaccine during pregnancy.

Since persons given measles, mumps, or rubella vaccine viruses do not transmit them (although virus shedding does occur), these vaccines can be administered safely to children of pregnant women. Although live polio virus is shed by persons recently immunized with OPV (particularly following the first dose), this vaccine also can be administered to children of pregnant women. Polio immunization of children should not be delayed because of pregnancy in close adult contacts. Experience to date has not revealed any risks of polio vaccine virus to the fetus.

There is no convincing evidence of risk to the fetus from immunization of pregnant women using inactivated viral or bacterial vaccines, or toxoids. A previously unimmunized pregnant woman who may deliver her child under unhygienic circumstances or surroundings should receive two properly spaced doses of Td before delivery preferably during the last two trimesters. Incompletely immunized pregnant women should complete the three-dose series. Those immunized more than 10 years previously should have a booster dose.

There is no known risk to the fetus from passive immunization of pregnant women with IG (see above).

TABLE 5 Vaccination during pregnancy

|

|

Vaccine |

Indications for vaccination during pregnancy |

|

Live virus vaccines |

|

|

|

Measles |

Live-attenuated |

Contraindicated. |

|

Mumps |

|

|

|

Rubella |

|

|

|

Yellow fever |

Live-attenuated |

Contraindicated except if exposure is unavoidable. |

|

Poliomyelitis |

Trivalent live-attenuated (OPV) |

Persons at substantial risk of exposure may receive live-attenuated virus vaccine. |

|

Inactivated virus vaccines |

|

|

|

Hepatitis B |

Plasma derived or recombinant produced. purified hepatitis B surface antigen |

Pregnancy is not a contraindication. |

|

Influenza |

Inactivated type A and type B virus vaccines |

Usually recommended only for patients with serious underlying disease. It is prudent to avoid vaccination during the first trimester. Consult health authorities for current recommendations. |

|

Poliomyelitis |

Killed virus (IPV) |

OPV not IPV, is indicated when immediate protection of pregnant females is needed. |

|

Rabies |

Killed virus Rabies IG |

Substantial risk of exposure. |

|

Inactivated bacterial vaccines |

|

|

|

Cholera Typhoid |

Killed bacterial |

Should reflect actual risks of disease and probable benefits of vaccine. |

|

Plague |

Killed bacterial |

Selective vaccination of exposed persons. |

|

Meningococcal |

Polysaccharide |

Only in unusual outbreak situations. |

|

Pneumococcal |

Polysaccharide |

Only for high-risk persons. |

|

Toxoids |

|

|

|

Tetanusdiphtheria (Td) |

Combined tetanusdiphtheria toxoids, adult formulation |

Lack of primary series, or no booster within past 10 years. It is prudent to avoid vaccination during first trimester. |

|

Immune globulins, pooled or hyperimmune |

Immune globulin or specific globulin preparations |

Exposure or anticipated unavoidable exposure to measles, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, rabies, or tetanus. |

YELLOW FEVER ENDEMIC ZONES IN THE AMERICAS

NOTE: Although the "yellow fever endemic zones" are no longer included in the International Health Regulations, a number of countries (most of them being not bound by the Regulations or bound with reservations) consider these zones as infected areas and require an International Certificate of Vaccination against Yellow Fever from travelers arriving from those areas. The above map based on information from WHO is therefore included in this publication for practical reasons.

In addition to areas shaded, CDC recommends vaccination for entire state of Mato Grasso in Brazil.

Example 3

TRIAGE OF THE INJURED PLANT

|

Clinical orientation: |

Clinical conditions |

|

Clinical purpose: |

Evaluation and management |

|

Complexity: |

Medium |

|

Format: |

Triage decision chart, free text, and trauma scoring table (Chapter 3 is provided as an excerpt) |

|

Intended users: |

Practitioners and prehospital care personnel |

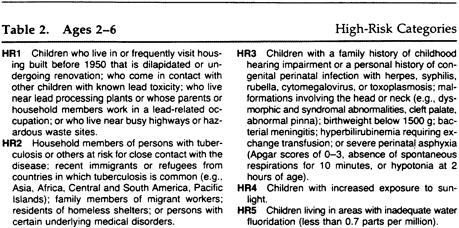

This item is actually a chapter from a longer document that is concerned with optimal care of the injured patient. It was produced by the American College of Surgeons' Committee on Trauma. The excerpt deals with field triage (essentially the decision of whether to move an injured patient to a trauma center or to evaluate and manage the patient at a local hospital) and with calculation of a well-known, widely used trauma score (which can be the first step in the triage decision as well as a factor in deciding on interhospital transfers).

This guideline was chosen for several reasons. First, the formatting facilitates quick evaluation of a patient and timely decision making—critical elements for the circumstances in which the guideline would be used. Second, the report also explicitly notes that it "replaces similar documents published in 1976, 1979, 1983, and 1986/87. It is generally recognized that this document is a set of guidelines representing current thinking for optimal care of the injured patient. Further revisions will be published at timely intervals as new information becomes available" (p. 1). In keeping with the emphasis on providing up-to-date information, the book arrives with a sheet of emendations on self-sticking label paper and directions for placing them in the report.

Third, the guideline addresses a broad category of clinical conditions—those that result from injury. The full report focuses on reducing preventable deaths, and it notes the need to balance surgical education and the provision of optimal care. The text also offers discussion of such issues as: systems development; treatment protocols; specific subspecialties of trauma care such as musculoskeletal, pediatric, or eye care; and issues more closely related to policy than to clinical care such as quality assurance concerns, geographically disparate resources, populations, and personnel, and cost-effectiveness considerations. As an example of the last (policy) category, see the discussion in the excerpted free text (p. 18) of acceptable levels of undertriage and overtriage and the relationship between the two-the stated assumption being that in minimizing undertriage (i.e., minimizing the provision of inadequate care to injured patients), some level of overtriage (and therefore overuse of resources) may be inevitable.

CHAPTER 3

FIELD CATEGORIZATION OF TRAUMA PATIENTS (FIELD TRIAGE)

Triage is the classification of patients according to medical need. There are three applications of this process in the early management of the trauma patient: 1) field triage: 2) interhospital triage to specialized care facilities: and 3) mass casualty triage.

Trauma patients who, because of injury severity, require care at Level I or Level II trauma centers, constitute a fraction of all patients hospitalized each year for trauma. In 1983. approximately 3.75 million patients were hospitalized for injury. In the same year. a study revealed 450 patients per million had an Injury Severity Score (ISS) of 15 or more, accounting for only 5.7 percent of all patients who were discharged from the hospital. Only 8.9 percent of the patients had severities greater than ISS 10. which incorporates just one serious body injury personnel. Even with high over-triage rates, it is unlikely that the number of patients entering trauma centers will exceed 1.00 per million per year. 1.000 per million per year.

It is a substantial challenge for field personnel to identify that small proportion of patients who require prompt access to trauma centers. Furthermore, time is critical. Of the trauma victims who are going to die, 50 to 60 percent do so before reaching a hospital. Of the remaining who die in-hospital, about 60 percent do so within the first four hours.

The following factors must be considered in field triage: 1) the actual or potential level of severity of the injured patient: 2) medical control: and 3) the regional resources available to treat the patient. including time and distance.

ASSESSMENT OF PATIENT SEVERITY

For the purpose of field triage, assessment of patient severity is based on examination of the patient for 1) abnormal physiological signs; 2) obvious anatomic injury; 3) mechanism of injury; and 4) concurrent disease

A triage decision scheme based on current scientific knowledge is illustrated in Table 1.

MEDICAL CONTROL

The triage decision determines the level and intensity of initial management of the major or multiple trauma patient. The vast majority of trauma deaths occur within a few hours of injury. The triage decision is often germane to patient survival or death. It is for this reason that the highest available level of medical expertise should be brought into the triage decision-making process. Usually this process will involve advice and guidance from physicians who provide medical control to prehospital personnel. On-line physician medical control is vitally important in emergency medical systems for the trauma patient.

Surgeons, emergency physicians, and prehospital-care should work together to develop prehospital triage protocols for trauma patients. In most instances of triage based on potentially severe injuries. the patient "triage based on potentially severe injuries, the patient is unable to make an informed decision in selecting appropriate hospital care. The "system" is often responsible for this decision. The system must, therefore. make surrogate decisions. In no instance may these decisions prejudice patient outcome. Disposition decisions at the scene must hold the patient's interests and needs paramount.

RANGE OF RESOURCES; TIME AND DISTANCE FACTORS

Both the level of available hospital resource and time/ distance factors also are considered in making the triage decision. It must be recognized that Level I through III trauma facilities are stratifications in a continuum of capability of commitment to trauma patient care. The system for trauma triage in an urban environment is considerably different from that in a rural environment. In the latter case access to any level of trauma care may involve a significant distance and time.

Each region must, therefore, structure a trauma system in a manner that ensures the prompt access to appropriate care and minimizes the risk of delay in diagnosis, delay in surgical intervention, and inadequately focused care, which are responsible for most of the preventable deaths that occur.

URBAN TRIAGE

In most urban communities in the United States, prompt access to a Level I or Level II trauma center should be feasible within 30 minutes of activation of the EMS feasible within 30 minutes of activation of the EMS system. Many urban populations have more than reasonable access to sophisticated care because of the distribution of tertiary care hospitals that function as Level I trauma centers. Other hospitals that do not offer this level of care or commitment should be bypassed in favor of access to a trauma center.

RURAL TRIAGE

In the rural environment, an injured patient may be at substantial distances from a trauma center. Such patients should be initially treated at a Rural Trauma Hospital. In more remote rural areas, where Level III facilities are not available, staff should at least be trained in ATLS. Patients with major severe injuries should then be secondarily triaged to Level I or II trauma centers, should local resources prove inadequate for continued care (see chapter 15)

Just as the Level II trauma center provides the highest level of care available within most communities across the country, the importance of the Level I trauma the country, the importance of the Level III trauma facility cannot be overemphasized. Between rural and facility cannot be overemphasized. Between rural and urban environments there are geographic areas with urban environments, there are geographic areas with increasing distances between hospitals and decreasing population density. Some patients may require initial triage and resuscitation at a Level III Rural Trauma Hospital. This action may be preferred to primary patient transport from the scene to an urban tertiary care referral center. The EMS system should be structured to provide the patient timely access to the best available level of care indicated by the extent and nature of injuries received.

NOTES TO TABLE 1

Step I Physiologic status thresholds are values of the Glascow Coma Score, blood pressure. and respiratory rate from which further deviations from normal are associated with less than a 90 percent probability of survival. Used in this manner, prehospital values can be included in the admission trauma score and the quality assessment process.

A variety of physiologic severity scores have been used for prehospital triage and have been found to be accurate. The scores contained in the triage guidelines, however are believed to be the simplest to perform and provide an accurate basis for field triage based on physiologic abnormality.

Step II Even in the presence of normal physiology. it is important to evaluate the likely presence of injuries that should be treated in a trauma center. A patient who has normal vital signs at the scene of the accident may still have a serious or lethal injury. Accurate diagnosis of life. threatening injury at the accident scene is unlikely. Thus. it is essential to look for indications that significant forces were applied to the body.

Evidence of damage to the automobile can be a helpful guideline to the change in velocity 'V). A 'V of 20 mph will produce an ISS of greater than 15 in 90 percent of automobile crash occupants 'V can be estimated if one inch of vehicular deformity is equated toe approximate one mph of 'V

Step III Certain other factors that might lower the threshold at which patients should be treated in trauma centers must be considered in field triage.. These include the following:

A. Age Patients over 55 have an increased risk of death from even moderately severe injuries. Patients younger than 5 have certain characteristics that may merit treatment in a trauma center with special resources for children

B. Co-morbid Factors. The presence of significant cardiac, respiratory or metabolic diseases are additional factors that may merit the triage of with moderately severe head injury to trauma centers.

Step IV It is the general intention of these triage guidelines to select patients with an ISS of greater than 15 for trauma center care. Patients with this level of ISS have at least a 10 percent risk of dying from a single severe or multiple serious injuries. When there is doubt. the patient is often best evaluated in a trauma center.

CONTINUING EDUCATION AND EVALUATION

Because of acknowledged imperfections of current field triage and the importance of this process in the delivery of trauma patient care, it is essential to involve surgeons in the continuing education of prehospital care personnel, as well as in feedback to those personnel on the accuracy of their patient triage decisions. Undoubtedly, as decision rules are reviewed, and the results are reported back to the prehospital care personnel, the process of triage will improve.

OVER-TRIAGE AND UNDER-TRIAGE

A system has yet to be developed that reliably and correctly selects the patients for appropriate levels of care that might be available in a given region. As a result, there will always be a certain number of patients selected for trauma center care who could very adequately be handled at a community hospital (85 to 90 percent of all injured patients do not need trauma center care). These patients are referred to as over-triaged. Conversely, patients who are in need of trauma center care but fail to gain timely access to such care are referred to as under-triaged. Together, over-triaged and under-triaged patients combine to form a misclassification rate for any triage decision scheme or rule.

Over-triage and under-triage are interdependent. Considerable medical effort should be made to minimize the number of patients who are under-triaged in a trauma system, because these patients are at risk of dying. Lives may be saved or cost of care may be reduced by prompt access to the needed level of definitive care. There is also concern about the over-triage of patients; over-triage can produce overuse of trauma centers and may divert patients away from community hospitals.

Not all patients with apparent minor injuries can clearly be grouped as not needing trauma center evaluation. For example, a patient who suffers high-deceleration injuries is found to have a wide mediastinum on X-ray film in a rural emergency department. Because of the risk of a ruptured aorta, the standard of care would dictate that such a patient be promptly evaluated in a trauma center where an arteriogram and necessary surgical care were immediately available. A large number of patients who undergo X-ray studies for a wide superior mediastinum after trauma will not have a ruptured aorta. These patients might eventually exhibit only minimal injuries. They could represent an over-triage on trauma system statistics, yet the medical prudence of transferring such a patient group for trauma center evaluation could not be argued.

Studies have shown that a 35 to 50 percent over-triage may be required to maintain a minimum level of under-triage in a community. It also has been estimated that because of the small number of patients who really need to be in trauma centers, the impact of patient flow on an individual institution will be minimal, should this degree of over-triage exist. Clearly, the surgical community needs to be more concerned about under-triage and the medical consequences that result from inadequate use of a trauma system.

Example 4

EVALUATION OF CHEST PAIN IN THE EMERGENCY ROOM

|

Clinical orientation: |

Clinical condition (symptom state) |

|

Clinical purpose: |

Diagnosis |

|

Complexity: |

Medium |

|

Format: |

Free text, tables, and algorithm (excerpts provided) |

|

Intended users: |

Emergency room physicians and other physicians; patients and families |

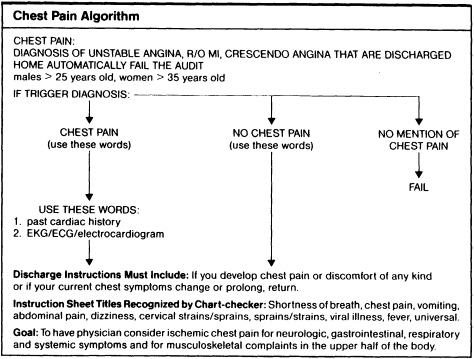

In 1984, the Massachusetts chapter of the American College of Emergency Physicians (MACEP) developed a set of guidelines focused on continuous monitoring of patient care in high-risk clinical areas as a part of the Massachusetts Emergency Medicine Risk Management Program. The guideline reproduced here is part of this large-scale effort (which includes medical record auditing, data analysis, and feedback) to obtain a malpractice discount for emergency room physicians insured by the state's Joint Underwriters Association. The guidelines, which are developed by consensus, are published as one-page summaries with commentary and/or references from the literature and as individual algorithms. The algorithms are meant to indicate the critical actions that physicians in the emergency room should document for the high-risk diagnostic problem covered by the algorithm.

The excerpt given here is for the assessment of chest pain in the diagnosis of (possible) ischemic heart disease (see the guideline's ''Appendix A. MI/Unstable Angina/New Onset Angina"). It indicates what the physician should take account of and document; it is basically intended to "alert the emergency physician to think of ischemic chest pain in the adult patient in terms of ischemic equivalents in addition to pain itself (p. 289). It also includes an instruction sheet for those patients for whom ischemic disease has presumptively been ruled out and who are therefore being discharged (the "Chest Pain Instruction Sheet" of the guideline's Appendix A). Finally, a separate portion of the guideline gives the algorithm related to this particular guideline (the guideline's "Appendix B. Chest Pain Algorithm").

SOURCE: Karcz, A., and Holbrook, J. The Massachusetts Emergency Medicine Risk Management Program. QRB (Quality Review Bulletin) 17:267292. 1991. Used with permission.

|

MI/Unstable Angina/New Onset Angina History: Pain in chest, jaw, upper abdomen (indigestion), arms Quality: burning, crushing, tight, pleuritic, sharp Radiation: left/right arm, jaw, back OR neurologic, respiratory, gastrointestinal symptoms without pain. Associated symptoms: SOB, nausea, diaphoresis, syncope, vomiting Risk factors: smoking, ASVD, hypertension, family history, obesity, diabetes, cocaine use, cardiac history Physical examination: Chest wall abnormalities/tenderness Lungs: rubs, adventitial sounds Cardiac: rubs, clicks, murmurs EKG: Helpful if abnormal or changed from previous EKG. All bets are off if EKG normal. Defend your diagnosis: Support your diagnosis from history, physical examination, associated symptoms, and risk factors. Watch out for: pneumothorax, aortic dissection, pulmonary embolus. If sending home: Document history, physical exam, and EKG as appropriate for discharge diagnosis. Give specific followup instructions. Assessment of Chest Pain as the Presentation of Ischemic Heart Disease It needs to be stated from the outset that at the present state of the art, it is not possible to diagnose ischemic heart disease with 100% accuracy. The best of clinicians will miss a certain percentage of cases and will undoubtedly admit many cases in which acute myocardial infarction will be ruled out. Given this, perhaps the most important element relating to proper evaluation of chest pain in the Emergency Department is a thorough and thoroughly documented history, physical examination, and appropriately evaluated EKG. The decision to admit a patient should not be dependent on an abnormal electrocardiogram, since, in fact, a normal electrocardiogram does not rule out acute ischemic heart disease. History The history should specifically note the presence or absence of the following: Chest pain: (or its equivalent, e.g., heartburn, indigestion, discomfort, arm or jaw pain.) Associated symptoms: Diaphoresis, nausea, anxiety, palpitations, shortness of breath, "sense of doom," weakness. Other symptoms without chest pain or equivalent: Syncope, shortness of breath, weakness, dizziness. Past medical history: Known coronary artery disease (history of angina or myocardial infarction), nitroglycerin use. It may also be useful to elicit information regarding the duration, type, location, radiation and aggravating/relieving factors relating to the pain. Risk factors (sex, age, hypertension, family history, cigarette smoking, diabetes mellitus, cholesterol) may also be elicited and recorded. |

|

Chest Pain Instruction Sheet You have been evaluated for chest discomfort and even though you are being allowed to go home, please follow the instructions below. Rest at home today. Take medications prescribed as instructed. Return to the Emergency Department by ambulance: 1. If chest pains, heaviness or pressure should develop and lasts longer than several minutes. 2. If you have known Angina and your chest discomfort is worse, lasts longer, comes on with less exertion, or is not relieved by the usual amounts of Nitroglycerin. 3. If you develop any shortness of breath, sweats, vomiting or nausea with your chest discomfort. 4. If your chest discomfort seems to travel into either of your arms, neck, back, jaw or stomach or otherwise changes in nature. Even if you feel better and have no further discomfort, you should follow up with your own doctor tomorrow. |

Example 5

USING ERYTHROCYTE SEDIMENTATION RATE TESTS IN DIAGNOSIS

|

Clinical orientation: |

Technology (diagnostic test) |

|

Clinical purpose: |

Diagnosis |

|

Complexity: |

Medium |

|

Format: |

Free text, tables, and figures (excerpts provided) |

|

Intended users: |

Practitioners |

This item, which consists of excerpts from a longer piece, is taken from a landmark monograph published by the American College of Physicians, Common Diagnostic Tests, which was discussed in Chapter 2. As is true of the entire monograph in its original 1987 version and in the revised edition of 1990, the intent of this guideline is to clarify the appropriate use of a long-established (and perhaps overused) test.

The recommendations are organized according to different patient states or characteristics: asymptomatic persons; problems of interpretation in symptomatic patients; patients with vague, unsubstantiated illness; cancer; temporal arteritis and polymyalgia rheumatica; estimating iron stores; inflammatory arthritis; suspected infection; an extreme or unexplained increase; and monitoring disease activity. Like certain of the other items in the appendix, it specifically focuses on the questions of when the service (here a diagnostic test) is indicated and when it is not.

Apart from its clinical significance, this guideline is of interest for formatting, as it makes use of free text, graphics, and tables. As is true of several other items in the appendix, it cites directly the literature on which its conclusions and recommendations are based. Shown here are the discussion of problems of interpretation in symptomatic patients and in patients with vague, unsubstantiated illness; a figure; and a summary table.

SOURCE: Sox, H.C., Jr., and Liang, M.C. The Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate. Guidelines for Rational Use. In H.C. Sox, Jr., ed. Common Diagnostic Tests. Philadelphia, Pa.: American College of Physicians, 1987; 2nd ed., 1990. (Excerpts are from pages 209-212, 214.) Used with permission.

PROBLEMS OF INTERPRETATION IN SYMPTOMATIC PATIENTS

The ESR is sometimes used to provide confirmation when the history and physical findings point toward a diagnosis. The test is also used when the patient's chief complaint is not supported by evidence for a specific disease. In this situation, the physician uses the ESR to screen for any serious disease that may be present. Clinical studies have not provided sufficient information to define the role of the test in these two applications.

To evaluate the ESR in symptomatic patients, one must ask how well it predicts disease. The probability of a disease corresponding to an ESR result may be calculated with a Bayes theorem (14). Bayes theorem requires that the pretest probability of the disease and the sensitivity and specificity of the ESR for the disease be known. Unless both sensitivity and specificity are known, a test cannot be interpreted in all situations.

The sensitivity of the ESR has been measured in many diseases, but its specificity has been measured accurately only a few times (15,16). To understand why past studies are so limited, consider the design of an ideal study. The ESR is measured in all patients suspected of having a disease. All patients, regardless of the ESR results, undergo a definitive diagnostic procedure. Some study patients have the disease and the sensitivity of the test is measured in them. The specificity of the ESR is measured in study patients who do not have the disease. In contrast to this ideal study design, the study populations in past studies have comprised only patients with a disease and have not included patients who were suspected of having the disease but did not. Because the specificity of the ESR for a disease has seldom been measured in the appropriate population, the frequency of a normal ESR in healthy persons is sometimes used as a proxy. This approach leads to error because the specificity of the ESR for a disease will be higher in healthy persons than in patients suspected of having the disease, who often have other diseases that increase the ESR. In one study, the frequency of an ESR greater than 20 mm per hour was zero in 32 normal reference subjects, 0.42 in 149 cancer-free reference subjects, and 0.62 in 68 patients with cancer (17). The frequency of an increased ESR in the cancer-free reference subjects shows the lack of specificity of an increased ESR in sick people.

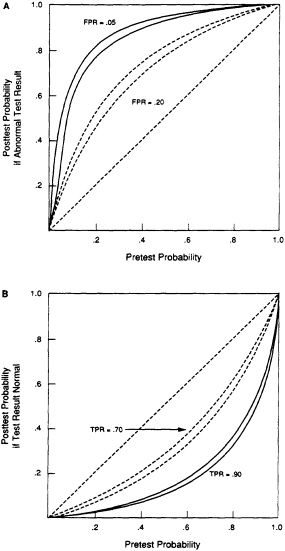

The shortcomings of studies of the ESR affect only the interpretation of an abnormal ESR. As shown in Figure 1A, test specificity largely determines the probability of disease when the ESR is abnormal. Because the specificity of the ESR for most diseases is not known, the post-test probability when the ESR is abnormal cannot be calculated. When the ESR is normal, the sensitivity of the test determines the post-test probability of a disease (Figure 1B). Because the sensitivity of the ESR for many diseases is known, a normal ESR can be interpreted, even if its specificity is not known.

FIGURE 1. Relation between pretest probability of disease and post-test probability. The post-test probability was calculated with Bayes theorem. Figure 1A. The probability of disease in a patient with an abnormal test result. Two values for the false-positive rate (FPR) were assumed. For each value, the sensitivity of the test was assumed to be 0.9 (top curve) and 0.7 (bottom curve). Figure 1B. The probability of disease for a normal (or negative) test result. Two values for the sensitivity of the test (true-positive rate, TPR) were assumed. For each value, the false-positive rate of the test was assumed to be 0.2 (top curve) and 0.05 (bottom curve).

PATIENTS WITH VAGUE, UNSUBSTANTIATED ILLNESS

Physicians often obtain an ESR in patients whose history and physical findings do not suggest any cause for their illness. These patients' pretest probability of serious disease is presumably very low, perhaps nearly as low as that in asymptomatic persons. Although too little is known to be certain, several considerations suggest that the ESR is generally not useful in these patients.

In principle, either a normal or an increased ESR could be diagnostically useful. In practice, neither result is very useful A normal ESR can exclude temporal arteritis, but the test is too often normal in other diseases to be of much value in excluding serious disease. An increased ESR is a clue to unsuspected serious disease but it is seldom present in patients with vague, poorly characterized complaints. As discussed in the preceding section, too little is known to interpret an increased ESR with confidence. However, when the pretest probability of disease is low, the post-test probability will be low unless the ESR is markedly elevated. The probability of some form of serious disease is probably relatively high when the ESR exceeds 50 mm/h, because a markedly increased ESR seldom occurs in healthy people. For example, in one population survey the ESR exceeded this rate in only 4 of 1462 apparently healthy women (15). However, the probability of a markedly increased ESR is very low when the pretest probability of disease is very low (14). This reasoning is substantiated by the very low frequency of an increased ESR in persons with unsuspected disease (Table 3).

These considerations suggest that the ESR is not very useful when the patient's symptom is unsubstantiated by the other clinical data. However, clinical studies of the ESR have not been done in such patients, and a precise recommendation cannot be made at present. Many diagnosticians will choose to focus on possible psychophysiologic explanations for the symptom and allow the evolution of the symptom over time to determine the need for diagnostic testing.

Table 3 Effects of Doing the Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) as a Screening Procedure

|

Study Description (Reference) |

Definition of Abnormal ESR |

Patients with Increased ESR |

ESR as Only Clue to Diagnosis |

|

|

mm/h |

n/n (%) |

n(%) |

|

Random sample of Swedish women; 6-year follow-up (9) |

>30 |

78/1462 (5.3) |

0 |

|

Clinic patients: 10-year follow-up (10) |

>30 (men) |

|

|

|

|

>35 (women) |

790/9140 (8.6) |

|

|

Male clinic patients: no follow-up (11) |

>20 |

Not given |

1+ (0.05) |

|

Surgical admissions: 6 to 42-month follow-up (12) |

|

99/6148 (6.0) |

1§ (0.06) |

|

Israeli airmen age 18-33; yearly follow-up for 15 years (13) 44/1000 (4.4) |

|

44/1000 (4.4) |

|

|

§ Patient died of prostate cancer 28 months after the index visit, at which there was no evidence of cancer and the ESR was 28 mm/h.

|

|||

Example 6

INDICATIONS FOR APPROPRIATE USE OF CAROTID ENDARTERECTOMY

|

Clinical orientation: |

Clinical condition |

|

Clinical purpose: |

Evaluation |

|

Complexity: |

High |

|

Format: |

Free text, tables, and diagrams (excerpts provided) |

|

Intended users: |

Health sciences researchers, policy analysts, and practitioners |

In the mid-1980s, the RAND Corporation developed appropriateness criteria for the use of six specific clinical procedures; indications for carotid endarterectomy were one of the six topics. The procedures were chosen for evaluation according to the following criteria: they are frequently performed, use substantial medical resources, and exhibit significant variation in rates of use across large geographic areas of the United States.

The immense array of possible indications for carotid endarterectomy (excerpts of which are shown in the example) is not, strictly speaking, a guideline; rather it is a detailed analysis and categorization of indications for use of the procedure. Thus, it is closer to being a set of medical review criteria than a tool for shared decision making by physician and patient (the IOM definition of practice guidelines). Using these indicators requires translating the indications into computer algorithms, or learning to read tens of pages of charts such as those included here, or both.

Several of the examples in this appendix are products of a consensus or expert panel; in this case, the process also involved significant analytic and logistical support from the sponsoring organization. The development process included rigorous analysis of all the literature in the subject area, although individual recommendations (indications) are not tied directly to that literature. Like Example 3, on triage of injured patients, and Example 5, on the use of erythrocyte sedimentation rates, this guideline implicitly considers the cost-effectiveness of resource use. Finally, the initial definitions of clinical conditions, the literature analysis, and the process of getting data from practicing physicians are carefully and extensively documented.

SOURCE: Merrick, N.J., Fink, A., Brook, R.H., et al. Indications for Selecting Medical and Surgical Procedures—A Literature Review and Ratings of Appropriateness: Carotid Endarterectomy. R-3204/6-CWF/HF/PMT/RWJ. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND, 1986. (Excerpts are from pages 48-55.) Used with permission.

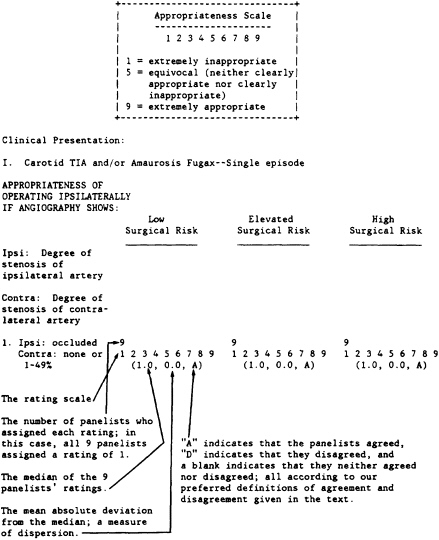

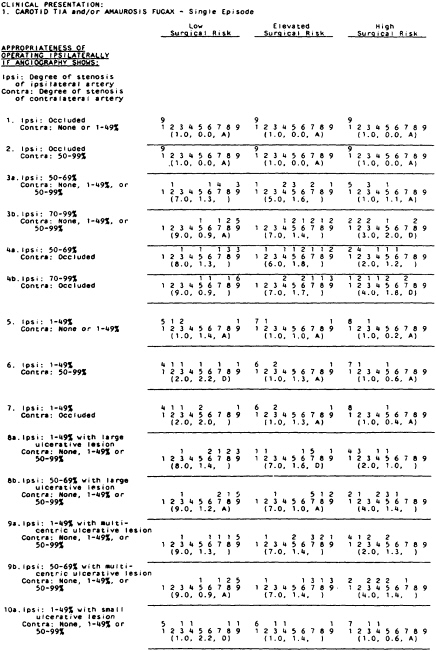

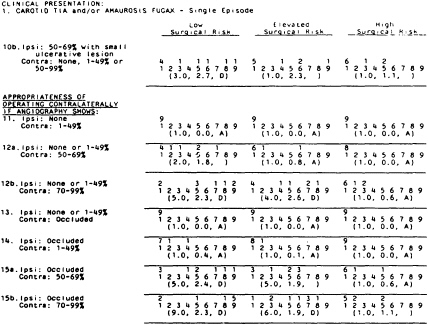

RESULTS

The following is the final list of rated indications for carotid endarterectomy. Figure 3 provides a key to reading the results. Note that the first indication for carotid endarterectomy is for a patient with a single episode of carotid TIA or amaurosis fugax whose surgical risk is low and whose angiogram demonstrates an occlusion of the ipsilateral artery and less than 50 percent stenosis of the opposite artery.

This indication received a rating of 1 (extremely inappropriate) by all nine panelists; the median rating was 1.0. Because of the unanimity of the rating the dispersion was 0.0, and panelists agreed on the rating.

INDICATIONS AND RATINGS

DEFINITIONS USED BY THE PANELISTS AT THE TIME THEY RATED THE INDICATIONS FOR CAROTID ENDARTERECTOMY

-