Appendix D

Summary of Updates from the Innovation Collaboratives

The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education is complemented by the work of four university- or foundation-based collaborations in Canada, India, South Africa, and Uganda. Known as innovation collaboratives (ICs), these country-based collaborations characterize innovators in health professional education through their demonstration projects that require different health professional schools to work together toward a common goal. The four ICs were selected through a competitive application process. By being selected, these collaboratives receive certain benefits and opportunities related to the forum that include

- The appointment of one innovation collaborative representative to the Global Forum,

- Time on each workshop agenda to showcase and discuss aspects of the IC’s project with leading health interprofessional educators and funding organizations,

- Written documentation of each collaborative’s progress summarized in the Global Forum workshop summaries published by the National Academies Press, and

- Remote participation in Global Forum workshops through a video feed to the collaborative’s home site.

Each collaborative is undertaking a different 2-year program of innovative curricular and institutional development that specifically responds to one of the recommendations in the Lancet Commission report or the

2011 IOM report The Future of Nursing—reports that inspired the establishment of the Global Forum. These on-the-ground innovations involve a substantial and coordinated effort among at least three partnered schools (a medical school, a nursing school, and a public health school). As ad hoc activities of the Global Forum, the ICs are amplifying the process of reevaluating health professional education globally so it can be done more efficiently and effectively, and it is hoped it will increase capacity for teamwork and health systems leadership. The work of the collaboratives is detailed below.

CANADA

PROGRESS REPORT FOR THE INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE

Maria Tassone, M.Sc., B.Sc.P.T., and Sarita Verma, L.L.B., M.D., CCFP University of Toronto

Introduction

The Canadian Interprofessional Health Leadership Collaborative (CIHLC) is a multi-institutional and interprofessional partnership whose goal is to develop, implement, evaluate, and disseminate an evidence-based program in collaborative leadership that builds capacity for health systems transformation. The CIHLC work is grounded in the principles of social accountability and community engagement and is embedded in a context of interprofessional and relationship-centered care. The program will be targeted at emerging health care leaders who are in positions that enable them to create sustainable change with their communities.

The CIHLC lead organization is the University of Toronto partnered with the University of British Columbia, the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, Queen’s University, and Université Laval. The project is supported by the five universities as well as the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC).

In the past year, CIHLC investigators completed the foundational research to understand the concept of collaborative leadership and design an educational program to develop collaborative leaders. The research involved

- A review of scientific and gray literature on the concept of collaborative leadership for health systems change,

- A review of educational programs for the development of collaborative leaders in health care,

- An environmental scan of existing programs for the development of collaborative leaders, and

- The completion of key informant interviews with thought leaders in health and education.

Across these four streams of research, the unique elements of collaborative leadership (e.g., transformational leadership, social accountability, collaborative decision making) were identified. In addition, there was found to be broad consensus that collaborative leadership is needed to support transformational system change within the health system to better meet the needs of patients, care providers, communities, and health system sustainability.

Through the foundational research, the CIHLC discovered that Canada contained a small number of leading collaborative leadership education programs for health care professionals. To reduce system redundancy and enhance existing opportunities, the CIHLC decided to partner with the University Health Network’s (UHN’s) Collaborative Change Leadership (CCL) Program for the 2014–2015 cohort to offer and evaluate an advanced program aimed at senior and high-potential leaders in health care and health education. This Integrated CCL Program 2014–2015 (the program) will be the CIHLC proof of concept.

Over 9 months (May 2013 to December 2013), the CIHLC

- Designed the CIHLC education program and Capstone Project components;

- Partnered with the CCL Program to create the Integrated CCL Program 2014–2015;

- Commenced recruitment of learners for the program through email blasts, website advertising, and targeted emailing of eligible individuals and organizations by members from the five partner universities and the UHN partners;

- Co-developed and implemented a recruitment and communication strategy for the 2014–2015 program, including the launch of a website and brochure;

- Begun to develop the modules for in-class and online learning; and

- Conducted a process evaluation of the CIHLC project to ensure that next steps are conducted efficiently and effectively.

The CIHLC in conjunction with the CCL is in the process of creating

- An Integrated CCL Program curriculum for the 2014–2015 cohort,

- A Learning Management System (LMS) for program delivery,

- A knowledge dissemination and knowledge transfer strategy for CIHLC scholarship, and

- An evaluation framework to measure program quality and impact.

Key Developments: May 2013 to December 2013

Design of the CIHLC-CCL Integrated Program

Through an iterative process the CIHLC in partnership with the UHN’s CCL Program has designed the Integrated CCL Program for 2014–2015. The Program targets senior and high-potential leaders in health care and health education who have completed general leadership courses and are looking for advanced specialized training in collaborate leadership founded on community engagement and interprofessional practice. The Program combines face-to-face and online learning, and includes a Capstone Project.

Grounded in leadership, change and social accountability theories, processes, and practices, this Program is designed for leaders who are driven to engage communities in a meaningful way and to create and sustain system changes that enhance the health of underserved populations. The Capstone Project teaches learners to develop, implement and evaluate a community-centered project that meets the needs of an underserved priority population, which includes frail elderly, aboriginal peoples, mental health, noncommunicable diseases/chronic illness, youth and women, and lower socioeconomic status. The focus of the Project is on, but is not limited to, interprofessional care and education, quality and safety, and patient/family/community-centered care.

Feedback from learners participating in the 2014–2015 cohort will ensure that the modules continue to evolve to maximize quality and impact.

Learning Management System (LMS) for Program Delivery

Taking into account the various modalities of course delivery and learner needs, the CIHLC has organized the course structure through the Blackboard LMS. This multilingual, internationally available platform will allow the Integrated CCL Program 2014–2015 to provide distance education through online tools such as webinars, act as a depository for multimedia and interactive resources for the learners, and provide online assessment tools for educators.

Knowledge Dissemination (KD) and Knowledge Transfer (KT) Strategy

The CIHLC has developed a comprehensive KD and KT strategy and has established a wide online and offline presence through various social media outlets and print. Currently, information about the Integrated CCL Program can be obtained through press releases (http://cihlc.ca/news), Facebook (www.facebook.com/cihlc), LinkedIn (http://www.linkedin.com/company/3200229), Twitter (https://twitter.com/cihlc), and the official

Integrated CCL Program brochure available on the website. The official CIHLC project website (http://cihlc.ca) provides information on project activities and collaborative members. It is also being used to recruit, register, and direct learners to the Program, provide information on instructors and learning resources, and facilitate on-going engagement of alumni in the years following the first cohort of the Program.

The CIHLC has been presenting its research and work nationally and internationally by way of a workshop at the Canadian Conference on Medical Education (CCME); a keynote speech at the Academic Consortium for Complementary and Alternative Health Care (ACCAHC); and posters at the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT), Collaborating Across Borders IV (CAB-IV) and the IOM Global Forum conferences. For the most recent IOM Global Forum, the CIHLC created a poster titled Evaluating the CIHLC Collaborative Leadership Education Program.

Members of the CIHLC have also presented a workshop and poster on “Transforming Health Systems through Collaborative Leadership: Making Change Happen!” at the 5th International Symposium on Service Learning (ISSL) in South Africa in November 2013, and have led a workshop at the “Network for Unity in Health” conference in Thailand in November 2013. The CIHLC is preparing several papers for publication, and a comprehensive publication strategy that will ensure dissemination of CIHLC research in prestigious journals.

Evaluation Framework

The CIHLC is using a developmental evaluation approach to guide the development of the program and assess its quality and impact. Learners participating in the 2014–2015 cohort of the Integrated CCL Program will be asked to provide on-going feedback which will be used to improve the Program to better meet the needs of the learners and support system transformation. As part of its own reflective processes, the CIHLC recently conducted a process evaluation to provide greater insight on the CIHLC team functioning. Results showed that supporting the development of relationships and fostering innovation leads to a valued Collaborative.

Next Steps

Over the next fifteen months, the CIHLC collaborative in partnership with the CCL Program will complete the development, implementation, and preliminary evaluation of the Integrated CCL Program 2014–2015 that will serve as the proof of concept for the CIHLC collaborative. Feedback from participants and continual scanning of the literature will be used to refine and enhance the Program and knowledge dissemination and knowl-

TABLE D-1 CIHLC Program Overview

|

|

|

| Session | Dates |

|

|

|

| Session 1 – Discovering What Is | April 11–12 |

| Session 2 – Imagining the Possibilities | May 30–31 |

| Session 3 – Designing & Implementing | September 19–20 |

| Session 4 – Sensing, Evaluating and Adapting | December 5–6 |

| Session 5 – Accomplishments, Reflection and Adaptation | January 30–31, 2015 |

| Capstone Project | Session 1–Session 5 |

|

|

|

INDIA BUILDING INTERDISCIPLINARY LEADERSHIP SKILLS AMONG HEALTH PROFESSIONALS IN THE 21ST CENTURY: AN INNOVATIVE TRAINING MODEL PROGRESS REPORT (APRIL 2012 TO DECEMBER 2013)

Sanjay Zodpey, M.D., Ph.D. Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI)

Background

The Lancet Commission report (Frenk et al., 2010) on Education of Health Professionals for the 21st Century discusses three generations of global educational reforms. It elaborates on transformative learning, focusing on development of leadership skills and interdependence in health education, as the best and most contemporary of the three generations. The purpose of this form of education reform is to produce progressive change agents in the field of health care. The Future of Nursing report (IOM, 2011) also strongly focuses on transformative leadership, stating that strong leadership is critical for realizing the vision of a transformed health care system. The report recommends a strong and committed partnership of nursing professionals with physicians and other health professionals in building leadership competencies to develop and implement the changes required to increase quality, access and value and deliver patient-centric care.

Leadership is a complex multidimensional concept and has been defined in many different ways. In the field of health care, leadership serves

as an asset to face challenges and is an important skill to possess. In order to reach this goal, common leadership skills must be looked for among students applying for health professional education, including medical, nursing, and public health professionals (Chadi, 2009). The Lancet Commission report’s recommendations are targeted at a multidisciplinary and systemic approach toward health professional education. In India, the lack of and need for professional health care providers has been discussed for the past many decades. The education system for health professionals in India is strictly compartmentalized and there are strong professional boundaries and demarcations among the various health professions (medical, nursing, and public health); there is recognized need for integrating these three streams. Moreover, the current health professional education system in India focuses minimally on the development of leadership competencies to address public health needs of the population.

Rationale for the Initiative

Health professionals have made enormous contributions globally to health and development over the past century. The demand of 21st-century health professional education is mainly transformational, aiming to help the professionals strategically identify emerging health challenges and innovatively address the needs of the population. The need of the hour in India is to amalgamate the skills and knowledge of the medical, nursing, and public health professionals and to develop robust leadership competencies among them. This initiative proposed to identify interdisciplinary leadership competencies among doctors, nurses, and public health experts necessary to bring about a positive change in the health care system of the country.

Objectives of the Initiative

- Identification of interdisciplinary health care leadership competencies relevant to the medical, nursing, and public health professional education in India.

- Conceptualization of and piloting an interprofessional training model to develop physician, nursing, and public health leadership skills relevant for the 21st-century health system in India.

Partners of the Innovation Collaborative

The Innovation Collaborative is a partnership among the following three schools:

- Public Health Foundation of India, New Delhi: public health institute;

- Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences, Sawangi, Wardha: medical school; and

- Symbiosis College of Nursing, Pune: nursing school.

These schools teamed up to further the objective of the Innovation Collaborative.Table D-2 provides basic information of the three schools.

Innovation Collaborative Activities—Update

The three partner institutes collaborated to address the major objectives of this initiative. A formal approval of the proposal was obtained by the IOM, following which the team members conducted various outlined activities.

TABLE D-2 Innovation Collaborative Partners

| Name of School | Address | Administrative Point of Contact | Members of Working Group |

| Public Health Foundation of India | Public Health Foundation of India, ISID, 4 Institutional Area, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi 110070, India | Prof. Sanjay Zodpey | Dr. Preeti Negandhi Ms. Kavya Sharma Dr. Himanshu Negandhi Ms. Ritika Tiwari |

| Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College–constituent college under Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences (Deemed University) | Paloti Road, Sawangi Meghe, 442004, Wardha District, Maharashtra State, India | Pro-chancellor Dr. Vedprakash Mishra | Dr. Abhay Gaidhane Dr. Zahir Quazi |

| Symbiosis College of Nursing–constituent of Symbiosis International University | Symbiosis College of Nursing (SCON) Senapati Bapat Road, Pune, 411 004, Maharashtra (India) | Col. Jayalakshmi N. | Dr. Rajiv Yeravdekar Mrs. Meenakshi P. Gijare |

1. Constitution of the collaborative

A team was formed including members from all three partner institutes. Professor Sanjay Zodpey, Director-PHE, PHFI represents the Collaborative as the National Program Lead along with Col. Jayalakshmi N., Principal, Symbiosis College of Nursing, and Dr. Vedprakash Mishra, Pro-chancellor, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences as Regional Program Leads. The team also included other member representatives from each partner institute.

2. Constitution of a Technical Advisory Group (TAG)

The TAG was formed, comprising renowned experts in the field of health professions education. All these members were contacted for seeking their consent to be a TAG member to oversee and provide guidance to the activities of the Collaborative. Regular meetings were held with the TAG members and their guidance was sought on various aspects of the project.

3. Identification of interdisciplinary health care leadership competencies

The initial activity undertaken by the Collaborative was an exhaustive literature search by the working group under the guidance of the Program Leads to understand need for and genesis of leadership competencies as a part of education of health professionals. Published evidence, both global and Indian, was included in the literature search to look for key interdisciplinary leadership competencies, the need for an interdisciplinary training of health professionals, and the current scenarios in interprofessional health education. The literature search strategies included journal articles from electronic databases, medical journals, grey literature, newspaper articles, and papers presented in conferences. The search was not restricted by the period of publication or language. The electronic search was complemented by hand searching for relevant publications/documents in their bibliographies. A process of snowballing was used until no new articles were located.

4. Expert group meetings

Once the literature search was complete, the working group summarized the findings of the search and prepared a formal report. This report was reviewed by all senior members and finalized. This was followed by a consultation with experts from various disciplines of health professional education, where the findings of the literature search were presented.

5. Development of training model

The next activity of the project was the development of the training model for the pilot. The training model was conceptualized based on the findings of the literature search and the recommendations of the expert group at the consultation. A training manual was developed for use in the trainings by the working group along with the team leaders.

The trainings are aimed at health professionals across the country from the medical, nursing, and public health fields. The long-term objective of this training model is its integration into the regular curriculum of the medical, nursing, and public health students, with an aim to develop interdisciplinary leadership skills among them.

To align with the objectives of the Innovation Collaborative, the training model was pilot-tested on some in-service professionals and students across the three streams. For this, a detailed agenda and the training material were prepared based on the content of the training manual.

6. Piloting the training model

The pilot trainings commenced in April 2013 and were completed in the first week of May 2013. These trainings were conducted in batches at three different sites:

- State Institute of Health Management and Communication, Gwalior (SIHMC),

- Indian Institute of Public Health, Bhubaneswar (IIPHB), and

- Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences, Sawangi (DMIMS).

The duration of each training batch was 3 days. Resource faculty from the three partner institutes actively trained the participants. IIPHB had 25 participants for the training, while SIHMC and DMIMS had 16 and 25 participants, respectively. The average age of the participants across all the three batches was 32 years. The total number of males in the three batches was 40, while there were 26 females.

The group for each batch of the training workshop was mixed, with participants from different disciplines. The training was aimed at bringing the three disciplines (medical, nursing, and public health) together to build interdisciplinary leadership skills. Details of participants are mentioned in Table D-3.

The pilot training workshops included didactic sessions as well as group discussions. The didactic sessions were aimed at giving the trainees an understanding of leadership skills and their importance in health care. The aim of the group discussions was to train them to innovatively apply interdisciplinary leadership competencies in their local health care settings.

TABLE D-3 Participants at Training Workshop

|

|

||

| Name of Institute | Participants from Medical, Nursing, and Public Health | Total Participants |

|

|

||

| Indian Institute of Public Health Bhubaneswar (IIPHB) | 14 medical, 2 nursing, 9 public health | 25 |

| State Institute of Health Management and Communication, Gwalior (SIHMC) | 11 medical, 4 nursing, 1 public health | 16 |

| Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences, Sawangi, Wardha (DMIMS) | 14 medical, 8 nursing, 3 public health | 25 |

|

|

||

At the end of the pilot trainings, the trainees were asked to fill out a feedback form about various aspects of the training. Positive responses from the participants were many, ranging from good coordination of the training, suitable content, good pedagogy, to friendly atmosphere. A few negative points, such as short duration of the training, more theoretical, less group discussions/practicum, were also emphasized.

Following the pilot trainings, a formal report was prepared by the working group and shared with the Global Forum at the IOM.

7. Revision of the training model

Based on the feedback of the trainees, the training model was revised. The duration of the training was increased to 4 days. Certain topics—such as ethics of leadership, advocacy, conflict resolution, negotiation, and interpersonal communication—were added to the program. The program was revised to include group discussions and role plays wherever necessary.

This revised model was shared with members of the TAG for their inputs and accordingly finalized. A copy of the final training model is enclosed herewith.

Prospective Activities Planned

- The activities undertaken as part of the Innovation Collaborative will be published in a peer-reviewed journal (see Table D-4). A draft of the manuscript is under way and will be submitted to a suitable peer-reviewed journal soon.

- The Collaborative will also present the findings of the initiative to the Global Forum on Innovation in Health Professional Education.

TABLE D-4 Innovation Collaborative Activities—Update Summary

|

|

||

| Activity | Current Status | Remarks |

|

|

||

| Constitution of the Collaborative | Completed | Team formed comprising of members from three partner institutes |

| Constitution of the Technical Advisory Group | Completed | Regular meetings held and advice sought from members regarding project |

| Conducting a literature review | Completed | Report has been shared with the IOM |

| Expert group meetings and consultation | Completed | Inputs taken from experts from the field |

| Developing training model | Completed | Training manual has been shared with the IOM |

| Piloting the training model | Completed | Trainings were completed in May 2013 |

| Preparation of report based on pilot findings | Completed | A formal report was prepared and shared with the IOM |

| Finalization of training model | Completed | The training model has been revised to incorporate the changes suggested by the participants of the pilot trainings and inputs of the TAG members |

| Manuscript submission to peer-reviewed journal | On-going | |

|

|

||

SOUTH AFRICA

Marietjie de Villiers, Ph.D., M.B.Ch.B., M.Fam.Med., and Stefanus Snyman, M.B.Ch.B., DOM Stellenbosch University

Background

The Interprofessional Education and Practice (IPEP) strategy of the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (FMHS), Stellenbosch University (SU) (South Africa), was developed in 2010 and 2011 by a working group of representatives from all undergraduate programs at the FMHS, as well

as postgraduate nursing. In keeping with findings of Frenk et al. (2010), the IOM (2011), the IPEP (2011), and the WHO (2010), the revised strategy considered the pivotal role IPEP can play in equipping students as agents of change to effectively address the health needs of individuals and populations.

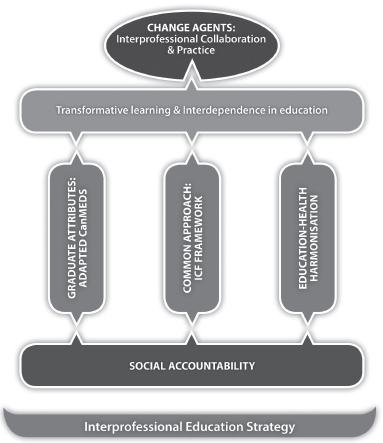

By integrating IPEP rather than it being a loose-standing curriculum, the working group sought to develop health professionals as “competent collaborative patient-centred practitioners” (Oandasan and Reeves, 2005, p. 46) who can reform health systems. To institutionalize a culture of IPEP, three focus areas were identified (see Figure D-1):

FIGURE D-1 The interprofessional education and practice strategy at the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University.

NOTE: ICF = international classification of functioning, disability, and health.

SOURCE: De Villiers et al., 2014.

- Development, integration, and assessment of core competencies in curricula (Stephenson et al., 2002), based on the CanMEDS roles (Frank, 2005) and the core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice (IPEC Expert Panel et al., 2011).

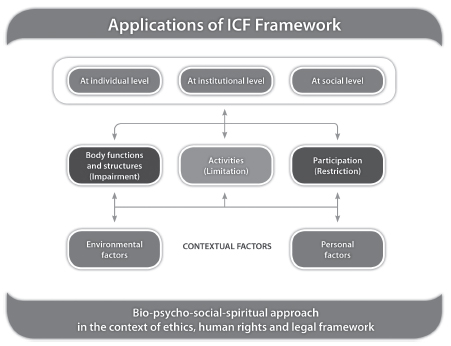

- Promotion of an interprofessional care and collaboration framework, based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) as common language between professions at individual, institutional, and social levels (WHO, 2001; Allan et al., 2006; Tempest and McIntyre, 2006; Dufour and Lucy, 2010; Cahill et al., 2013). See Figure D-2.

- Cultivation of interdependence (harmonization) between two key stakeholders in HPE: higher education (university) and service providers (provincial and district health departments and community-based organisations). The aim was to develop trust relationships and build capacity among faculty and service providers in modelling interprofessional practice (Clark, 2004; Lawson, 2004; Steinert, 2005; Craddock et al., 2013).

FIGURE D-2 The ICF as interprofessional care and collaboration framework (adapted from WHO, 2001).

SOURCE: De Villiers et al., 2014.

The gradual implementation of this strategy commenced in the undergraduate community-based modules at SU’s Ukwanda Rural Clinical School, where disciplinary silos were perceived to be less entrenched and where learning activities were being experienced as more flexible than in the tertiary environment and therefore open to creative innovation (De Villiers et al., 2014). Despite this, typical challenges of IPE were prominent, e.g., the short duration of rotations, shift incompatibility, issues of profession-specific supervision, and claims that accreditation requirements by professional boards are not flexible enough to allow for IPEP (Lawson, 2004; Freeth et al., 2005; Oandasan and Reeves, 2005; Jacobs et al., 2013; Thibault and Schoenbaum, 2013). There were logistic challenges such as medical students were placed for a 2-week rural clinical rotation in one of nine sites in a 150-kilometer radius from the medical school. Students from the other aforementioned undergraduate programs were only sporadically present at three of these sites. For these challenges to be solved an alternative approach was adopted.

Facilitators were appointed at each site to facilitate IPEP between students and the various health professions and to build the capacity of local health professionals to model interprofessional collaboration and practice. During their rural rotation, medical students worked with these health professionals in managing their patients interprofessionally. A local interprofessional team assessed students as they presented their patients using the ICF framework. These assessments included peer discussions, where formative feedback was provided.

A study was conducted to establish how using the ICF in IPEP was experienced by medical students, preceptors (student placement supervisors), and patients. The results of this study were reported to the Global Forum in October 2012.

Progress During 2013

- The findings of the study were presented at the annual conferences of the South African Association of Health Educationalists (SAAHE), the Association of Medical Educators in Europe (AMEE), and the Council for Social Work Educators (CSWE) (plenary).

- A full-day preconference workshop was held at the 5th International Service-learning Symposium exploring how the pedagogy of service learning (in combination with the IPEP) can facilitate transformative learning in health professions education.

- Contributions to two chapters in different WHO publications on the value of the ICF in IPEP and community-based education were published:

• WHO (World Health Organization). 2013. How to use the ICF: A practical manual for using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Exposure draft for comment. October 2013. Chapter 3. Geneva: World Health Organization.

• De Villiers, M. R., H. Conradie, S. Snyman, B. B. Van Heerden, S. C. Van Schalkwyk. 2014. Chapter 8: Community Based Education in Health Professions: Global Perspectives. In Experiences in developing and implementing a community-based education strategy—a case study from South Africa, edited by W. Talaat and Z. Ladhani. Cairo: WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean.

- A total of 892 undergraduate health professions students at SU and the University of the Western Cape were trained during 2013 to apply the ICF framework as interprofessional approach to patient care and public health.

- The University of KwaZulu-Natal (SA) and the Northwest University (SA) indicated that they want to join our collaborative. Further negotiations will be conducted during the first semester of 2014.

- Ethical clearance for a more comprehensive study in the application of the ICF in IPEP was obtained. The first round of data was collected and is currently being analyzed.

- Stellenbosch University and the University of the Western Cape will start with a two monthly IPE World Café in 2014 involving medicine, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech-language and hearing therapy, social work, natural medicine, pharmacy, dental hygiene, dentistry, and nursing.

- A total of 172 health professionals (doctors, psychologists, social workers, dental assistants, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nurses, speech therapists, and dieticians) were trained in using the ICF as approach to IPP in the Cape Winelands District Municipality, Cape Metro (Cape Town), eThekwini (Durban), and the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

- The Western Cape Provincial Health Department incorporated parts of the ICF as part of its discharge summary in hospitals.

- The Collaborative forms part of a new initiative of the Functioning and Disability Reference Group of the WHO to develop a mobile application for using the ICF as catalyst for interprofessional collaboration and practice.

- The initiative was a poster presentation winner at the WHO’s Family of International Classifications annual meeting and conference in Beijing (October 2013) and subsequently requested to present

to a joint sitting. Twenty-six international collaborators signed up to participate in this project.

Mobile Application to Capture Patient Information

The relevance of the ICF has been demonstrated in community-based rehabilitation (CBR) and community-oriented primary care (COPC) and IPEP. However, the pivotal role of data on functioning and context are often overlooked in mobile applications designed to capture patient information.

Currently, no mobile applications incorporate the ICF. It is envisaged that the mICF, in providing a means to collect and transfer ICF-related information, could support continuity of care. The aim of this project is to develop an ICF mobile application (mICF) to

- ensure accurate and efficient capture of functional status and contextual information;

- convey information securely between service providers in different service settings consistent with ethical and privacy principles in relation to data sharing, e.g., among health professionals;

- facilitate clinical decision making by making person-centred data readily available;

- facilitate administration and reporting through data aggregation; and

- minimize the need for repeat data collection.

It is envisaged that the mICF could provide a means to collect and transfer ICF-related information; add value to interprofessional collaborative practice; improve continuity of care; and contribute to more efficient and cost effective health systems.

UGANDA

Nelson Sewankambo, M.B.Ch.B., M.Sc., M.D., F.R.C.P., L.L.D. (HC) Makerere University

Defining competencies, developing and implementing an interprofessional training model to develop competencies and skills in the realm of health professions ethics and professionalism.

Innovation and Motivation for Selection of Innovation

This project is a major innovation aimed at contributing to improvement in the quality of health service. Although there is a lot of discussion

about the need to improve professional ethics and professionalism in low- and middle-income countries, there has been very little attempt to develop competency-based IPEPs to address the challenges. Professionalism is defined in several different ways (Wilkinson et al., 2009). The Royal College of Physicians (2005) has defined professionalism as “a set of values, behaviors, and relationships that underpin the trust the public has in doctors.” This definition can be extended to embrace all types of health workers.

Overall Aim: To prepare a future workforce committed to practicing to a high degree of ethics and professionalism and performing effectively as part of an interprofessional health team with leadership skills.

Specific Objectives

- To define competencies and develop a curriculum for interprofessional education of health professional students (nursing, medicine, public health, dentistry, pharmacy, and radiography) in order to develop their skills in the realm of ethics and professionalism.

- To pilot a curriculum for interprofessional education of health professional students (nursing, medicine, public health, dentistry, pharmacy, and radiography) to develop their skills in the realm of ethics and professionalism.

- To develop curriculum for interprofessional education for health workers and tutors in ethics and professionalism and pilot its implementation in partnership with the regulatory professional councils.

Approach to Implementation of the Project

Instructional Reforms

A critical element of this project will be the engagement of major stakeholders, including the Ministry of Health, patients, hospitals and health centers, private practitioners, professional councils, educators, students, alumni, and consumer rights groups nationally. This engagement will ensure the participation of stakeholders in the implementation and the commitment of local resources to support this effort. Through this engagement, the collaborative will define the extent of the problem (unethical and unprofessional practices among nurses, doctors, public health workers, and other health professionals) and identify the necessary interventions, including the required competencies and interprofessional training approaches that will address the gaps as well as the necessary post-training support to ensure the institutionalization of ethics and professionalism among health profes-

sionals in Uganda. Stakeholders will participate in the implementation of training and mentoring trainees at their respective places of work. Of particular importance are the students who have initiated the formation of a student ethics and professionalism club. They are advanced in the planning process and will be supported through this project and contribute to the whole process of this project. Right from the beginning, the collaborative plans to align this educational project with the needs of Uganda’s population. Concerns have been raised about ethics and professionalism among health professionals in Uganda, largely by the media. There are, however, only limited, brief reports in publications in the recent past in peer-reviewed literature on the issue of ethics and professionalism among health workers in Uganda (Hagopian et al., 2009; Kiguli et al., 2011; Kizza et al., 2011).

Some national reports highlight the challenges in this area, but few formal studies have been conducted to document the extent of the problem, the contextual factors, and possible interventions (UNHCO, 2003, 2010). Because of the lack of comprehensive evaluations and evidence, the collaborative plans to initiate this project with a systematic needs assessment. The needs assessment will involve the participation of representatives from several key partners mentioned previously. Data will be collected through an analysis of key documents from the professional councils, which are statutory units charged with the responsibility of investigating reports and cases of professional indiscipline among doctors, dentists, nurses, pharmacists, and others. The collaborative will undertake limited surveys and key informant interviews among the above-named groups.

Development and Implementation of the Curriculum

Results from the needs assessments will be used to inform the curriculum development process, which will employ a six-step approach (Kern et al., 2009). Prior to curriculum development, interprofessional competencies will be defined through stakeholder engagement and suggestions, building on the five competencies defined by the 2003 IOM report Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Trainees will learn not only competencies related to ethical practices and professionalism but also competencies of interprofessional collaboration and leadership (IPEC Expert Panel, 2011). Stakeholder discussions will be held to get a clearer understanding of society’s needs and the challenges of ensuring high standards of ethics and professionalism. This will be followed by a consensus process to arrive at an agreed-on set of competencies to be acquired during an interdisciplinary course for the students who are the next generation of leaders.

A curriculum will be developed for students and for teachers based on the needs assessment results and the defined competencies.

Institutional Reforms

A number of institutional reforms will be needed as the instructional reforms are implemented. These include a careful review of the linkages and collaboration between the university and the aforementioned stakeholders, and the recognition and the reward system for excellence in demonstrating the desired high standards of ethics and professionalism among both students and staff.

REFERENCES

Allan, C. M., W. N. Campbell, C. A. Guptill, F. F. Stephenson, and K. E. Campbell. 2006. A conceptual model for interprofessional education: The international classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Journal of Interprofessional Care 20(3):235-245.

Cahill, M., M. O’Donnell, A. Warren, A. Taylor, and O. Gowan. 2013. Enhancing interprofessional student practice through a case-based model. Journal of Interprofessional Care 27(4):333-335.

Chadi, N. 2009. Medical leadership: Doctors at the helm of change. McGill Journal of Medicine 12(1):52-57.

Clark, P. 2004. Institutionalizing interdisciplinary health professions programs in higher education: The implications of one story and two laws. Journal of Interprofessional Care 18(3):251-261.

Craddock, D., C. O’Halloran, K. McPherson, S. Hean, and M. Hammick. 2013. A top-down approach impedes the use of theory? Interprofessional educational leaders’ approaches to curriculum development and the use of learning theory. Journal of Interprofessional Care 27(1):65-72.

De Villiers, M. R., H. Conradie, S. Snyman, B. B. Van Heerden, and S. C. Van Schalkwyk. 2014. Chapter 8. Community based education in health professions: Global perspectives. In Experiences in developing and implementing a community-based education strategy: A case study from South Africa., edited by W. L. Talaat and Z. Cairo: World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean.

Dufour, S. P., and S. D. Lucy. 2010. Situating primary health care within the international classification of functioning, disability and health: Enabling the Canadian family health team initiative. Journal of Interprofessional Care 24(6):666-677.

Frank, J. R., and Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. 2005. The canMEDS 2005 physician competency framework: Better standards, better physicians, better care. Ottawa, Ontario: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Freeth, D. S., M. Hammick, S. Reeves, I. Koppel, and H. Barr. 2005. Effective interprofessional education: Development, delivery and evaluation. Edited by H. Barr. Vol. 5. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

Frenk, J., L. Chen, Z. A. Bhutta, J. Cohen, N. Crisp, T. Evans, H. Fineberg, P. Garcia, Y. Ke, P. Kelley, B. Kistnasamy, A. Meleis, D. Naylor, A. Pablos-Mendez, S. Reddy, S. Scrimshaw, J. Sepulveda, D. Serwadda, and H. Zurayk. 2010. Health professionals for a new century: Transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 376(9756):1923-1958.

Hagopian, A., A. Zuyderduin, N. Kyobutungi, and F. Yumkella. 2009. Job satisfaction and morale in the Ugandan health workforce. Health Affairs 28(5):863-875.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2003. Health professions education: A bridge to quality. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IOM. 2011. The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

IPEC (Interprofessional Education Collaborative) Expert Panel, American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy, and American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine. 2011. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

IPEC Expert Panel. 2011. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

Jacobs, J. L., D. D. Samarasekera, W. K. Chui, S. Y. Chan, L. L. Wong, S. Y. Liaw, M. L. Tan, and S. Chan. 2013. Building a successful platform for interprofessional education for health professions in an Asian university. Medical Teacher 35(5):343-347.

Kern, D., P. Thomas, and M. Hughes (Eds.). 2009. Curriculum development for medical education: A six-step approach, 2nd edition. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins Press.

Kiguli, S., R. Baingana, L. Paina, D. Mafigiri, S. Groves, G. Katende, E. Kiguli–Malwadde, J. Kiguli, M. Galukande, M. Roy, R. Bollinger, and G. Pariyo. 2011. Situational analysis of teaching and learning of medicine and nursing students at Makerere University College of Health Sciences. BMC International Health and Human Rights 11(Suppl 1):S3.

Kizza, I., J. Tugumisirize, R. Tweheyo, S. Mbabali, A. Kasangaki, E. Nshimye, J. Sekandi, S. Groves, and C. E. Kennedy. 2011. Makerere University College of Health Sciences’ role in addressing challenges in health service provision at Mulago National Referral Hospital. BMC International Health and Human Rights 11(Suppl 1):S7.

Lawson, H. 2004. The logic of collaboration in education and the human services. Journal of Interprofessional Care 18(3):225-237.

Oandasan, I., and S. Reeves. 2005. Key elements of interprofessional education. Part 2: Factors, processes and outcomes. Journal of Interprofessional Care 19(Suppl 1):39-48.

Royal College of Physicians. 2005. Doctors in society: Medical professionalism in a changing world. London, UK: Working Party of the Royal College of Physicians of London.

Steinert, Y. 2005. Learning together to teach together: Interprofessional education and faculty development. Journal of Interprofessional Care 19(Suppl 1):60-75.

Stephenson, K. S., S. M. Peloquin, S. A. Richmond, M. R. Hinman, and C. H. Christiansen. 2002. Changing educational paradigms to prepare allied health professionals for the 21st century. Education for Health (Abingdon) 15(1):37-49.

Tempest, S., and A. McIntyre. 2006. Using the ICF to clarify team roles and demonstrate clinical reasoning in stroke rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation 28(10):663-667.

Thibault, G. E., and S. C. Schoenbaum. 2013. Forging collaboration within academia and between academia and health care delivery organizations: Importance, successes and future work. Commentary, Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC. http://www.iom.edu/forgingcollaboration (accessed July 26, 2013).

WHO (World Health Organization). 2001. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

WHO. 2010. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/index.html (accessed February 5, 2013).

Wilkinson, T. J., W. B. Wade, and L. D. Knock. 2009. A blueprint to assess professionalism: Results of a systematic review. Academic Medicine 84:551-558.

UNHCO (Uganda National Health Users’/Consumers’ Organisation). 2003. Study on patient feedback mechanisms at health facilities in Uganda. Kampala, Uganda: UNHCO.

UNHCO. 2010. Establishing incidence of health provider absenteeism in Bushenyi District. Kampala, Uganda: UNHCO.

This page intentionally left blank.