10

Translating Bullying Research into Policy and Practice

Key Points Made by Individual Speakers

- The adoption, implementation, sustainability, and scalability of an intervention receive much less study than efficacy, yet these are the factors that will determine whether an evidence-based intervention has a large-scale impact on a population. (Rohrbach)

- Even when implementing an evidence-based program, the fidelity of implementation varies greatly. (Rohrbach)

- Interventions designed to achieve multiple outcomes can produce both immediate and long-term positive outcomes, but monitoring and feedback to practitioners are needed to ensure fidelity of implementation. (Fagan)

As Denise Gottfredson, University of Maryland, said in introducing the panel on translating bullying research into policy and practice, developing effective interventions is just the first step in achieving high-quality implementation of effective practices on a large enough scale that they can make a substantial difference. Research on efficacy needs to be translated into effective policies and practices, as the three presenters on the panel observed. Although their talks were not necessarily specific to bullying prevention, by drawing more broadly from what has been learned about

sustainability and high-quality implementation of prevention practices in general, their observations can be applied to bullying prevention.

IMPLEMENTATION OF PREVENTION PROGRAMS IN SCHOOLS

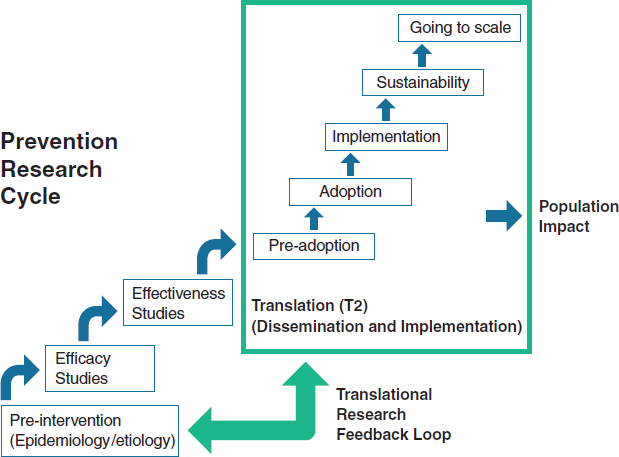

Research on interventions has a characteristic lifecycle (see Figure 10-1), noted Luanne Rohrbach, associate professor of preventive medicine and director of the Master of Public Health program at the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine. The initial stages of this lifecycle—pre-intervention studies, efficacy studies, and effectiveness studies—tend to receive considerable resources and emphasis, she said, while studies of the adoption, implementation, sustainability, and scalability of an intervention tend to receive much less attention. Yet, she said, these latter factors are the ones that will determine whether an evidence-based intervention has a large-scale impact on a population.

FIGURE 10-1 Prevention research tends to focus on efficacy and effectiveness, but dissemination and implementation are the steps that have the greatest impact on populations.

SOURCE: Rohrbach presentation, 2014. Data from NRC and IOM, 2009, and Spoth et al., 2013.

Efficacy has been established for an increasing number of empirically validated prevention interventions, Rohrbach said, but less is known about the effectiveness of these interventions when implemented under real-world conditions. In addition, reviews of evidence-based programs are available, best-practice guidelines have been published, and local communities are encouraged to implement only these “proven programs,” yet a gap persists, she said, between the development and testing of interventions and the implementation of those interventions.

As an example of this gap, Rohrbach briefly described a study by Ringwalt et al. (2009) that asked middle schools about their use of evidence-based programs for substance use prevention. The percentage of the schools that reported using an evidence-based program grew from less than 35 percent in 1999 to about 42 percent in 2005, but a greater increase had been expected over that period because of the implementation of a new policy that gave schools guidance in using proven programs when applying for funds for substance use prevention programs.

Challenges in Implementing Prevention Programs

As discussed by previous presenters, schools face many challenges in implementing prevention programs, including a focus on academic achievement, limited time and resources, school reform measures, staff turnover, and a limited capability to monitor implementation and collect outcome data. Schools also have complex decision-making processes that are used to determine which interventions will be implemented and how, Rohrbach said, and the decisions have stakeholders at many levels. Furthermore, many schools have inadequate access to tools for decision making about prevention. Finally, Rohrbach said, schools have inequitable resources and limited funding for sustained prevention efforts.

Rohrbach and other researchers have examined the factors that influence the adoption and use of evidence-based programs in schools, and those factors can be divided into three categories, Rohrbach said: program-related factors, organizational factors, and the characteristics of implementers (Rohrbach and Dyal, in press; Rohrbach et al., 2006).

The first category, she said, includes factors related to the program itself. Is it attractive and user-friendly, easy to use, and flexible? Are the methods familiar? Do they offer a perceived advantage over current practice? Does a program fit with an organization’s goals and work practices?

The second category includes organizational factors, including leadership, administrative support, the presence of program champions, a positive school climate, organizational norms, effective communication, openness to change, and existing capacity, Rohrbach said.

The third category includes the characteristics of the implementer. Those who are motivated, have a positive attitude toward the program, are comfortable with the approach, have the skills to implement the program, and have a strong sense of self-efficacy are more likely to adopt and implement a new evidence-based prevention program than those without those characteristics, Rohrbach said.

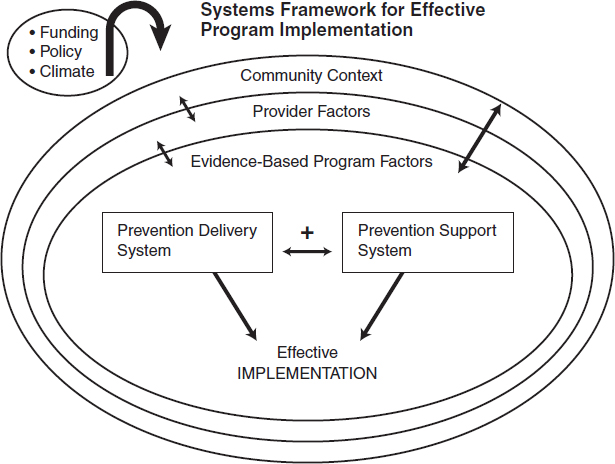

Several frameworks have been published that bring these categories together, Rohrbach said. One such framework includes barriers and facilitators at multiple levels of influence (see Figure 10-2). Complex interactions occur among the factors at the various levels that influence whether the implementation will be effective, Rohrbach said. The framework also emphasizes the importance of infrastructure and the capacity for prevention program delivery, she noted. For example, the training of implementers and other school personnel is extremely important. It can result in greater self-efficacy and confidence, a higher level of skill, more motivation, and more positive attitudes toward the program. There is clear evidence that training is associated with stronger implementation fidelity. Some evidence

FIGURE 10-2 Effective implementation is a product of multiple interactions among programs, providers, and the community. SOURCE: Rohrbach presentation, 2014. Data from Durlak and DuPre, 2008.

also suggests that ongoing training, or technical assistance, enhances implementation, Rohrbach said.

Organizational capacity, which is part of the delivery system, includes resources (e.g., funds and staffing), managerial and administrative support, effective partnerships with other organizations, and data systems for continuous quality improvement, Rohrbach said. All of these factors increase the chances that a program will be implemented effectively and in a way that faithfully reflects the intentions of the program’s developers, she said.

Implementing Interventions with Fidelity

Fidelity to the intentions of a program can be measured in several ways, Rohrbach said, and adherence, dosage, and engagement are all important factors to consider. Fidelity varies greatly in school settings, she said. Some schools implement interventions with high fidelity, while others do so with much less fidelity. Teachers have reported eliminating key modules, not using interactive materials, and otherwise deviating from the program as written, she said, and combining lessons from more than one program is a common practice.

Many studies have demonstrated that fidelity is important and is associated with outcomes. As an example, Rohrbach cited the Adolescent Alcohol Prevention Trial from the 1990s (Rohrbach et al., 1993). The degree of fidelity to which the program was implemented had a substantial impact on program acceptance, substance use attitudes, program-specific knowledge, behavioral intentions, and resistance skills, she said, with high-fidelity implementations being associated with more positive outcomes.

Despite such findings, the tension between fidelity and adaptation persists, Rohrbach said. Unintentionally and intentionally, implementers modify programs in various ways in order to increase their cultural relevance, address participants’ cognitive-information processing and motivation, and improve the fit between program and context, she said. It is also the case that more flexible programs are more likely to be implemented and sustained. However, little is known about the effects of adaptation on outcomes, she said, and some evidence indicates that it can result in poorer outcomes.

Guided or planned adaptation can overcome some of these problems, Rohrbach said. Ideally, the process of guided adaptation involves an interaction with the program developer. It needs to be theory based, to provide options within or among program components, to conceptualize a program as a process rather than a standardized set of activities, and to develop and adhere to guidelines for cultural adaptations, Rohrbach said.

Implications for Practice and Research

Rohrbach concluded by providing several implications that her observations have for practice. Implementers should

- Conduct readiness assessments

- Develop a broad base of supporters for programs and involve stakeholders in planning

- Establish leadership

- Implement strategies to build capacity

- Integrate prevention programs with the school’s primary mission (learning) and ongoing prevention delivery systems in the community

- Develop systems for collecting data that will guide implementation and continuous quality improvement

- Develop better systems of information about what is available and how it might fit locally

- Increase the understanding of what program implementation involves

She also listed several implications for researchers. They should

- Develop assessments of prevention program outcomes that can easily be used by schools as part of their accountability process

- Evaluate the implementation of evidence-based programs under real-world conditions

- Investigate how varying models of training and technical assistance affect implementation and student outcomes

- Ground programming in the realities of the school setting

- Conduct more cost–benefit analyses

- Investigate the effects of adaptations

- Conduct research on how evidence-based programs work to identify key ingredients

THE COMMUNITIES THAT CARE SYSTEM

Communities That Care is a prevention system rather than a program, explained Abigail Fagan, an associate professor at the University of Florida. It is designed to build the capacity of communities to do evidence-based prevention regardless of the behaviors being prevented or promoted, and it is a community-driven approach that takes into account the differences among communities and the problems they are facing. “A one-size-fits-all approach may not be the best model,” she said. “We want something that

can be community specific.” For example, communities differ in levels of youth delinquency, levels of risk and protective factors related to delinquency, resources, capacity, norms, and values, and, as noted in Chapter 7, youth behavior is affected by the community context.

Communities That Care emphasizes a comprehensive and coordinated approach to prevention, Fagan said. It relies on local practitioners and stakeholders to take ownership for what they want to see change in their community and then to work together collaboratively to get there. It is driven by the use of science to assess the needs and behaviors in a community, to match those needs with evidence-based practices, and to make sure that those new practices are implemented with fidelity so that they can achieve their intended outcomes, she said.

The system has five phases, which Fagan reviewed in the context of a randomized controlled study that tested the effectiveness of Communities That Care in reducing delinquency, substance use, violence, and other problem behaviors (Hawkins et al., 2014). Twenty-four communities located in small to medium-size towns in seven states were randomly assigned to carry out either the Communities That Care approach or prevention as usual, and key leaders came together in the getting-started phase to create a coalition of stakeholders. The organizations represented by community board leaders in the 12 communities participating in Communities That Care represented businesses, citizen advocacy organizations, community coalitions, health agencies, human service agencies, the juvenile justice system, law enforcement, local philanthropies, the media, parents, religious groups, schools, substance abuse prevention organizations, local governments, youth, and youth recreation programs. Communities That Care is not just a school program, Fagan said; it involves many participants and contributors. “Everybody has a role to play,… and individuals in the community are there to support those efforts,” she said.

Once the coalition has passed through the getting-organized phase, Fagan explained, it enters the third phase, which involves collecting information about the specific issues that need to be addressed in a community. This is done primarily through a school-based survey called the Communities That Care Youth Survey, which is designed to be done in middle and high schools. Youth self-report their exposure to risk factors and protective factors in their communities, families, and schools and among their peers. The results of the surveys can vary substantially from community to community, Fagan said, reflecting different levels of risk and protective factors.

Once the data are collected, she continued, the coalition uses them to create a community action plan aimed at reducing the specific risk factors that are elevated in their communities and at increasing the protective factors that are depressed. Coalition members have a menu of effective evidence-based prevention programs, drawn from the Blueprints for

Healthy Development website, that have already been tested and shown to meet evaluation criteria and to significantly improve youth health and behavior (see Chapter 7). Because the number and range of programs selected are based on community needs, they can differ from community to community, Fagan said.

Schools are often the hardest organizations to convince to adopt new programs, Fagan said, for the reasons cited by Rohrbach and other presenters. But over the 4 years that communities were funded to implement programs, all of them did adopt school programs, she said. Schools were part of the coalitions, and they were partners in efforts to determine what the communities could do, she said.

Communities That Care also helps communities adopt a fidelity-monitoring system that includes training for all program implementers, fidelity “checklists” used by implementers to rate their adherence to the program guidelines, observations to rate the adherence and quality of delivery, documentation of attendance, local monitoring and quality assistance by community coalitions, and external monitoring, Fagan said. “The broad-based implementation monitoring system was not easy to implement,” she said. “There was a lot of paperwork, a lot of moving parts, a lot of resistance on the ground. But the upshot was that we had high rates of implementation fidelity across the board” (Fagan et al., 2009).

As an example of how Communities That Care can be scaled up, Fagan briefly described an experience in Pennsylvania where the system was adopted as a statewide initiative beginning in 1994. More than 120 communities have been trained in the system, and there are about 60 coalitions currently active, Fagan said. Nearly 200 evidence-based programs have been replicated, and technical assistance is being provided to the coalitions to support healthy coalition functioning, to ensure high-quality implementation of evidence-based programs, and to promote the sustainability of the coalitions and programs. Fidelity is enhanced by requiring that the program developer visit the site and provide a stamp of approval, Fagan said, and external monitoring keeps the coalitions on track.

In summarizing the effects of Communities That Care, Fagan said that the approach has helped communities identify what works: increase local support for and use of effective prevention services; create an integrated and coordinated system of services; ensure high-quality implementation via structured protocols, continuous quality improvement, and community “pressure”; sustain prevention efforts over time; and realize community-wide reductions in problem behaviors.

The most recent evaluation of sustained changes in youth behaviors showed that communities using the Communities That Care system have substantially increased the number of youth abstaining from alcohol and avoiding delinquency compared to the control communities, Fagan said

(Hawkins et al., 2014). “Those are good outcomes that we hope to continue to see as we follow the kids who have grown up in these communities over time,” she said.

OVERCOMING BARRIERS TO EFFECTIVE IMPLEMENTATION OF BULLYING SCHOOL PREVENTION PROGRAMS

Dissemination and implementation studies can be divided into four categories, said Hendricks Brown, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and the Department of Preventive Medicine in the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. These four categories of studies are exploration, adoption and preparation, implementation, and sustainment. “It is really about making a program work,” Brown said. “How do you do that on the ground?”

From a scientific perspective, an important question surrounding implementation is whether it can produce generalizable knowledge. “Is it something that you can take from that particular study and extend and expand to other projects?” Brown asked. The other pertinent question involves local implementation: Can a given program be done locally?

Challenges to Program Implementation

Brown discussed three challenges in implementing prevention programs in schools. The first was making prevention an integral part of the school mission so that it is sustainable from the very beginning rather than as a last step.

He began by discussing a model developed by Russell Glasgow and his colleagues (1999). The model is known as RE-AIM in reference to its five dimensions:

Reach—What proportion of a population is exposed?

Effectiveness—Does a program work on outcomes?

Adoption—Do organizations take it up?

Implementation—Is a program delivered with fidelity?

Maintenance—Is a program sustained over time?

One or all of these dimensions can be the subject of research, but all must come together for successful implementation, Brown said. Trying to achieve all five of these aims simultaneously is one of the reasons why implementation can be so difficult, he said.

As an example of making prevention an integral part of the school mission, Brown cited a partnership model developed by Sheppard Kellam (2012) for use in the mental health field. The partnership includes school

districts, community organizations, researchers, and policy makers. In these partnerships, Brown said, the intervention program leader serves as the head of the technical and scientific staff. A community board serves as an overseer and adviser to ensure that community values and service agency guidelines are protected, he added.

Kellam developed several steps that need to be taken in establishing these partnerships, and Brown cited three in particular:

- Analyze which agencies’ and community organizations’ support is required.

- Determine the order of engaging with each leader.

- When trust has been established with each leader, suggest bringing together the needed partners around their determined mutual self-interests in a mutually agreed on site.

An important aspect of this approach, Brown said, is that it does not begin with a research program in search of a school willing to do an intervention. Rather, it takes the form of a collaboration between a school and researchers, with the goal of learning how a prevention program fits into a school’s context.

The second challenge that Brown discussed was how best to deliver programs that address multiple prevention targets. To illustrate, he discussed the Good Behavior Game and Familias Unidas. Both of these programs seek to affect drug use, HIV risk behaviors, depressive symptoms, and suicide attempts, he said, and both have produced immediate and long-term positive outcomes, including a reduction in aggression.

The third challenge Brown discussed was building and maintaining a fidelity monitoring system. Schools are normative organizations—that is, they are set up for everybody to attend and are usually not set up to do the detailed work of fidelity assessments, he said. Furthermore, schools generally do not have the resources to develop or maintain fidelity monitoring or feedback systems. However, he said, interventions need both high fidelity and participation by the target audience. Monitoring of fidelity, in turn, has to produce information that is delivered to those delivering the intervention, he said.

To explore this issue, Brown looked again at Familias Unidas, which is a parent-training intervention for middle-school Hispanic youth that is delivered in parent groups in schools and in family visits at home. Currently, school counselors are performing an effectiveness study, with a research team providing monitoring and feedback. But full-scale implementation will require an assessment system for costs, effectiveness, reliability, and fidelity. Given the resource limitations in the school, a decision was made to focus on the issue of joining. This engagement is a key part of

the intervention and is common to all interventions. Using computational linguistics with videotapes of sessions, ratings are produced for the training and supervision of counselors. In this way, Brown explained, counselors can learn about, for example, the importance of asking open-ended question. This is just a “a proof of concept,” he said. “It is not the whole thing, but it is one of the kinds of ideas that we think ultimately can help.”

Brown concluded with several lessons that follow from his research. Prevention needs to further a school’s primary mission, he said, with trust and mutual self-interest being established before the research agenda. In addition, he said, programs that have outcomes across multiple dimensions can be prioritized, and monitoring and feedback of a complex behavioral intervention is essential to ensure fidelity.

FIDELITY VERSUS ADAPTATION

During the discussion session, the conversation continued to center on the issue of whether programs need to be implemented with strict fidelity or can instead be adapted to local circumstances.

One aspect of Communities That Care that promotes fidelity is the amount of planning that goes on before programs are implemented, Fagan said. In choosing programs, one consideration is whether a program can be implemented with fidelity. That way, she said, programs are fitted for a setting so that it is not discovered after implementation that a program is a bad fit for local circumstances. “Communities do not always take the time upfront to think about what they are getting into, and then you are stuck trying to reactively fix the problem and cut corners,” she said. “This is one way of trying to avoid the problem.”

Rohrbach pointed to an approach in which, after a program is implemented, information is gathered from the implementers about adaptation and ideas for improvement of the program. These data then can be rated according to how consistent they are with a theory of the program. Conclusions that are consistent with the theory can be provided as options for people interested in adapting an intervention, she said. “There are probably a lot of smaller things that we could do in programs to make them more flexible in a planned and strategic way,” Rohrbach said. Furthermore, she added, researchers would be interested in such an approach, given their interests in seeing their programs implemented, and such an approach could help researchers identify the aspects of their programs that are most important.