8

Investing in Young Children and Their Caregivers

Investments in young children globally, from birth through primary school, have the potential for short- and long-term economic and social benefits by improving child health and caregiver well-being, thus strengthening the skills, capabilities, and health of the future workforce. Speakers explored specific investment topics such as cash transfer programs, investments in early child education programs and nutrition programs, and teacher development, as well as long-term potential benefits of each of these options as well as potential unintended consequences.

POLICY APPROACHES TO SUPPORTING CHILDREN’S DEVELOPMENT1

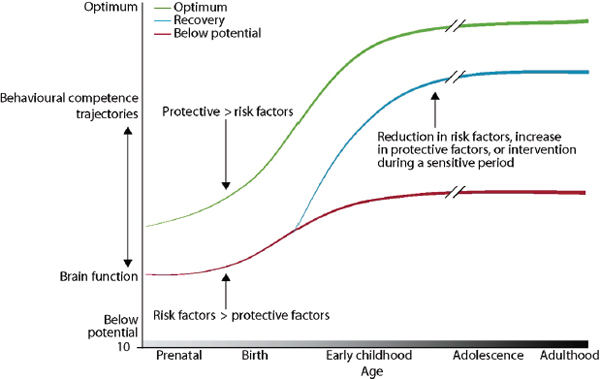

Lia Fernald explained that risk factors begin early in life. She presented a schematic (shown in Figure 8-1) that outlines optimal development (shown in green on the figure), development in which risk factors outweigh protective factors (shown in red), and the development curve when risk factors are reduced (shown in blue). Fernald is interested in attaining this blue curve by reducing risk factors through intervention during sensitive periods.

Fernald explained that there are a large number of intervention possibilities: early nutrition and health interventions such as breastfeeding and

__________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Lia Fernald, University of California, Berkeley.

FIGURE 8-1 Differing trajectories of brain and behavioral development as a function of exposure to risk and protective factors. The cumulative effect is illustrated by the progressive strengthening (darker lines) of the trajectories over time.

SOURCE: Walker et al., 2011.

iodine supplementation, parenting family support programs, preschool programs (though she noted that these range in quality, which affects outcomes), and social-sector approaches. Interventions are most effective when they target the most vulnerable populations, she said.

In her presentation, Fernald focused on social-sector approaches, particularly cash transfer programs. These programs usually involve giving cash to mothers, and can increase household income by as much as 30 percent (Fernald et al., 2011). The added income can help parents purchase basic needs, invest in children’s schooling, and focus on caregiving. There are two types of cash transfer programs:

- Conditional—In a conditional cash transfer program, cash is provided to a household to encourage compliance with a prespecified action; the cash also serves as a way to alleviate short-run economic pressure that the family may be facing. The action required by the program could be, for instance, attending school (for children), receiving health examinations, or consuming nutrition supplements. The quality of these programs varies, and Fernald noted that not every country has the infrastructure to sustain them.

- Unconditional—Unconditional cash transfer programs provide money to a household, with no established, related requirements that are linked to receiving the cash.

In a later discussion session, a participant asked Fernald about the pros and cons of conditional and unconditional cash transfers. Fernald noted that unconditional cash transfers are much easier logistically, as there is no need to track compliance. She said that the Mexico program is complex and requires detailed compliance records. She noted that a reported 97 percent of participants were compliant with the conditions (Benderly, 2013). She also stated that the outcomes may be different between conditional and unconditional cash transfer programs, but studies with head-to-head comparisons of the two types of programs have not produced clear results. One study about growth in children showed no differences between conditional and unconditional programs (Robertson et al., 2013), but another study showed differences in breastfeeding and vaccines when comparing conditional and unconditional cash transfers. This comparison is an area open for research.

Conditional cash transfer programs were first implemented in Brazil and Mexico in the 1990s. Fernald explained that cash transfer programs have inconsistent results for children (Fernald et al., 2011). In this review with her colleagues, Fernald found that there are generally positive effects on birth weight, illness, morbidity, behavioral development, prenatal care, maternal depression, growth monitoring, micronutrient supplementation, and household food consumption. There are mixed effects on height, weight, cognitive and language development, the presence of a skilled birth attendant, and receipt of childhood vaccinations. There is no perceived effect on hemoglobin concentration. Fernald posited that different cash amounts, differential requirements, different levels of compliance, and different initial rates of poverty or cultural differences may be some reasons that the results are heterogeneous.

After 10 years, Mexico’s conditional cash transfer program positively affected height, behavior (Fernald et al., 2008, 2009a; Ozer et al., 2012), and stress levels (Fernald and Gunnar, 2009), but no effects on body mass index, verbal performance, and cognitive performance (Fernald et al., 2009b). Cash transfers were associated with reductions in maternal depressive symptoms (Ozer et al., 2011) and improvements in children’s growth, verbal performance, and cognitive performance (Fernald et al., 2008, 2009a). The program also had unintended consequences. Increased cash also led to increased body mass index, obesity, and hypertension (Fernald et al., 2008). Higher levels of socioeconomic status have been associated with increased consumption of soda and alcohol (Fernald, 2007), suggesting a possible mechanism for the findings.

Throughout her work, Fernald discovered that reducing poverty is not sufficient, and that parenting support and parenting education are also important variables to improving conditions for children. Therefore, Fernald explained that a new Mexican program has added a childhood stimulation element (essentially a group parenting support class) to the existing cash transfer program. The addition of the childhood stimulation element may be critically important to improve cognitive outcomes for children. During the discussion period, a participant asked how to engage families in a program. Fernald noted that cash can be a powerful motivator.

Fernald then described a program in Mexico, in which dirt floors in homes were replaced with cement. This action correlated to reductions in maternal depression and had positive impacts on child growth and development (Cattaneo et al., 2009). She concluded by stating the most effective approaches to early child development use comprehensive approaches, including combinations of cash transfers and the direct promotion of child development.

INVESTING EARLY AND RETURN ON INVESTMENT2

Paul Gertler analyzed the long-term economic returns from investments in young children. He connected investment in young children with workforce skills that are necessary for economic productivity—both individual and global economic productivity. He emphasized the need for capabilities to bring individuals out of poverty and participate more fully in the workforce. He posed three main questions:

- How much human potential is lost if investments are not made?

- If investments are made, what is the correct age for intervention, and when is it too late?

- How can long-term inequality be reduced, beginning at an early age?

Gertler stated that 200 million children are at risk of not reaching their potential (Grantham-McGregor, 2007). This translates to a large potential loss in quality of life, including the lost potential for economic growth if people are unable participate actively in the economy. Presenting data from India, Indonesia, Peru, and Senegal, Gertler showed that differences begin early in life, at around 12 months (Fernald et al., 2011). Specifically, the data indicate that children from the wealthiest income quartile

__________________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Paul Gertler, University of California, Berkeley.

showed statistically significant gains over the children from the poorest income quartile. He also showed that poor children performed worse on language tests (Engle et al., 2011). Specifically, 5-year-old children in higher-income quintiles have better language performance relative to lower-income quintiles.

Early gaps may persist throughout a person’s lifetime (NRC and IOM, 2000), according to Gertler. He posited that interventions targeting the earliest period of life (before age 2 to 3) will have the highest rate of return, thus improving the efficacy of later interventions and eliminating the need for pricey remediation services later in life. Further, investment in the poorest populations will likely yield the greatest return, as there is the most potential for improvement. Investment in the poorest population also adds to the economy and reduces long-term inequality.

Gertler then discussed two specific intervention studies that provided evidence of a return on investment in the early years:

- Jamaica Psychosocial Stimulation Intervention, 1986 to 1987—This intervention consisted of home-based play sessions facilitated by community aid workers and a once-a-week class to improve the quality of mother–child interactions. The program found significant improvement in cognitive development sustained through age 17 for participants, but the intervention did not bring the stimulated group up to the level of a normal (not stunted) group (Walker, 2010). After 20 years, the group with intervention showed a 25 percent earnings increase over those who did not receive the intervention, and this increase brought their earning levels up to the level of the normal population (Gertler et al., 2013).

- Institute of Nutrition of Central America and Panama (INCAP) Nutrition Intervention, Guatemala, 1969 to 1977—This program provided a nutrition supplement known as Atole, a high-protein energy drink, along with Fresco, a less nutritious drink, to groups of young children. The treatment group showed significantly less stunting over time. At ages 25 to 42, researchers found income improvements equal to or greater than those in the Jamaica study. The gains were most significant when the supplement was given to children under 36 months of age. After 36 months, there was effectively no economic advantage to the supplement (Hoddinott et al., 2008).

Gertler concluded that early disadvantage leads to a long-term disadvantage, which is difficult and expensive to compensate for later in life. He also stated that investments in young children and their development

can improve future skills in the labor market in a cost-effective manner, which has a positive impact on long-term economic outcomes.

CONTINUITY OF INVESTMENTS INTO PRIMARY SCHOOL3

Norbert Schady explained that, in Latin America, many students arrive at school with deep deficits in the areas of nutrition, cognition, and language (Schady et al., 2014). These disparities have led to different social policies directed at children younger than school age, including

- Cash transfers—Programs have been implemented in many countries, and their effect on child development has been evaluated in Ecuador (Fernald and Hidrobo, 2011; Paxson and Schady, 2010), Mexico (Fernald et al., 2008, 2009a), and Nicaragua (Macours et al., 2012).

- Parenting interventions—Programs have been implemented in Colombia (Attanasio and Hernandez, 2014) and Jamaica (Gertler et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2011a). A nationwide parenting program is in the process of being implemented in Peru.

- Center-based care and preschool—Programs have been implemented in many countries, and evaluations are under way in Brazil (Barros, unpublished), Colombia (Bernal, unpublished), and Ecuador (Oosterbeek and Rosero, 2011).

Kindergarteners are a “captive audience,” according to Schady. The majority of 5-year-old children in Latin America attend school.4 He noted a great deal of progress in enrollment, and a closing enrollment gap between the lowest- and highest-income quintiles. He asked, “What developmental delays can be recovered at age 5?”

Schady presented results from a study of 200 schools in Ecuador (Schady and Araujo, 2006). Students with varying readiness levels were randomly exposed to kindergarten teachers of varying quality. More than 450 teachers were filmed for a full day, and their recordings were scored on a rating scale of 1 to 7 in three broad domains: social support, classroom organization, and instructional support using the Classroom Assessment Scoring System, or CLASS (Pianta et al., 2007). Across all teachers, the emotional support score was medium, with a fairly narrow distribution. The classroom organization score was high, with a fairly wide distribution, and instructional support was very low, with a narrow distribution.

__________________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Norbert Schady, Inter-American Development Bank.

4 Schady’s calculations are based on household surveys.

At the end of the year, students were given 12 tests in math, language, and executive function (response inhibition, working memory, attention, and cognitive flexibility). Teacher effects on student performance were then calculated by finding the average learning outcome per class relative to the school mean and finding the variance of teacher effects, correcting for sampling error. In general, the data show that teachers make a great deal of difference. If a teacher scored one standard deviation higher overall on the CLASS, the children in his or her class scored an average of 0.6 standard deviations higher. Children at all levels experienced this increase; in other words, better teachers are better for all students, not just the lowest-performing students. After correcting for measurement error, the CLASS score of the teacher accounted for 34 percent of the variation in within-school, cross-teacher learning outcomes.

According to the study, better teachers, as scored by the CLASS, did not affect child attendance or dropout rates; rather, they increased the amount of learning per day. The same teachers improved outcomes in all dimensions that were tested (math, language, and executive function). In response to a later question, Schady explained that the CLASS score analyzed 10 dimensions across 3 domains, and there was a strong correlation among the scores in the 10 dimensions for an individual teacher. Schady indicated that he did not have much confidence in the measures of the individual 10 dimensions, but the overall score accurately reflected the quality of the teaching.

Schady concluded by stating that what happens to a child before he or she begins school is very important, and there are currently large disparities in school readiness across socioeconomic class and place of residence. One contributing factor may be that differences in language, math, and executive function all correlate to the level of the education of the child’s mother. Across all tests, children whose mothers are elementary school dropouts scored about 0.5 standard deviations below children whose mothers graduated from elementary school, and around 1 to 1.5 standard deviations below those children whose mothers graduated from high school. However, good teachers in the primary school years can help to reduce those deficits. Schady suggested that programs be designed to better select teachers, provide more effective in-service training, and better compensate effective teachers.