9

Benefit–Cost Analysis of Inaction

In this section, speakers discussed how to determine the cost of inaction, including how to determine benefit–cost ratios using systematic tools and techniques, including decisions in the parameters used in such analyses; a country-level perspective on the political will to engage in investments in young children across sectors; and a measure of a country’s readiness to invest in young children and avoid costs of inaction.

COSTS OF INACTION VERSUS COSTS OF ACTION FOR INVESTING IN YOUNG CHILDREN GLOBALLY1

Jere Behrman explained that in considering the costs of inaction in investing in young children, costs of action should also be considered. He emphasized the need for a holistic approach that considers a life cycle framework, because investments early in life are likely to result in returns at a different (i.e., later) point in the life cycle. Behrman affirmed that benefit–cost ratios can be an effective guide for policy development and also noted that distributional weights can be included to meet particular policy aims. For instance, certain elements of early child development can be considered as human rights, and distributional weights can be used to incorporate that perspective. Challenges to benefit–cost approaches include the idea that benefits, such as improved health, reduced mortal-

__________________

1 This section summarizes information presented by Jere Behrman, University of Pennsylvania.

ity, and resources saved, are likely to be multiple, and it can be challenging to weigh different benefits to obtain a combined measure. Behrman presented evidence of associations among dimensions of early life and outcomes over the life cycle. For instance, Victora and colleagues (2008) showed positive associations between anthropometric measures at infancy and adult outcomes, such as level of schooling, adult height, labor income, and birth weight of offspring. Studies reviewed in Engle et al. (2007, 2011) indicate a positive association between attendance in ECD programs and future cognitive skills.

Benefits from an early intervention might not be realized until the child is an adult, Behrman said. He cautioned that future benefits should be discounted in today’s terms because there is an opportunity cost of not being able to use resources for other purposes in the meantime if one has to wait for benefits in the future. For instance, a benefit valued at $1,000, if it were to be received 10 years from now, would be worth $744 today (assuming a 3 percent discount rate) or $386 today (assuming a 10 percent discount rate). If the $1,000 benefit were to be received 60 years from now, it would be worth $170 today (assuming a 3 percent discount rate) or only $3 today (assuming a 10 percent discount rate).

Discount values can vary for each of seven major impacts of moving one infant out of low birth weight status in a low-income, developing country (Alderman and Behrman, 2006). The seven major impacts presented by Behrman were reduced infant mortality, reduced neonatal care, reduced costs of infant and child illness, productivity gains from reduced stunting, productivity gains from increased cognitive ability, reduced cost of chronic diseases, and intergenerational effects. He noted that impacts related to increased productivity showed the largest value because the impact is felt over many years. He also pointed out that there is disagreement in the community about how to value infant mortality. If it were valued highly enough, it would become the dominant value.

Resource costs, Behrman explained, include time, materials, and human effort, but this is generally not equal to provider expenditures. He noted that resource costs matter to society, not expenditures. For instance, the conditional cash transfer program described in Lia Fernald’s presentation has costs associated with running the program, but those costs are small relative to the governmental expenditures themselves, which are dominated by transfers that are not resource costs. Resource costs also include private costs, which can have a differential effect across populations. Behrman discussed an example of costs for acute malnutrition programs, studied by Levin and Brouwer (2014), in which costs vary across country because of the methods employed.

Behrman then showed data for benefit–cost estimates for nutritional interventions (Behrman et al., 2004). The benefit–cost ratios vary across

interventions, but the results are promising. For a single intervention, the benefit–cost ratio range is large because of different possible discount rates. However, while the range is large, it is usually greater than 1 in most cases, suggesting to Behrman that these are interventions worth undertaking. He also presented very large benefit–cost ratios for reducing rates of stunting for children (Hoddinott et al., 2013), but these benefit–cost ratios vary significantly across countries.

In showing the lasting positive effects of preschool (Engle et al., 2011), Behrman pointed out that there is significant variation by country. For example, countries with higher preschool enrollment have a smaller gap in attained schooling between the highest-income quintile and other quintiles. The estimated increase in future earnings provides a benefit–cost ratio ranging from 6.4:1 to 17:1 as a result of bringing enrollment rates for the bottom four quintiles up near those of the top quintile. Behrman cautioned that these are likely to be conservative estimates, as the only dimension considered in the benefit–cost is the nexus among preschool, school, and earnings. The likely benefit–cost ratio could be even larger. Behrman also presented results from a study in Uganda of the benefit–cost ratio of preschool attendance (Behrman and van Ravens, 2013), and cautioned that these estimates are very sensitive to the assumptions, such as base cost and discount rates.

Behrman concluded by stating that while the data presented show very high benefit–cost ratios for intervention programs, there is uncertainty with those ratios because of the different assumptions that are used. He noted that the benefit–cost ratios described are mostly for interventions for the poor. If this were framed as a human rights issue, and the value of human rights were weighted more heavily, the ratios would be even higher. He also noted that it is important to understand context and identify what data are context specific.

A COMPREHENSIVE COUNTRY-LEVEL APPROACH TO INVESTING IN YOUNG CHILDREN: COLOMBIA2

In many countries, Constanza Alarcón noted, the gap between scientific evidence and the development of policy is a very serious issue. Owing to the lack of quality data in Colombia, it is difficult to make decisions and develop actions that have an impact on childhood development programs to support families, provide nutritional support, and educate children. Despite this, however, Alarcón noted that Colombia is among many countries with access to early childhood education because a large

__________________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Constanza Alarcón, Presidency of the Republic, Colombia.

number of people can provide these services. Colombia has helped to generate skills, strengthen institutions, and ensure the development of quality services to support positive outcomes. Alarcón emphasized the importance of measuring quality. She stated that without quality actions, the services provided will not benefit children, and any investment made would be lost. Alarcón explained that a very detailed, holistic vision is needed to enable policy implementation. A program on nutrition, for example, must connect to emotional care, bonding, and access to other services. In moving toward an integrated system, Alarcón noted that it does not cost more to have a vision, but the cost of not having a vision can be very high.

For 3 years, the government of Colombia, as described by Alarcón, has used political will to work toward implementing early childhood development policies, based on the Convention of the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1990). Prior to this effort, each interest group (such as local authorities, the education sector, the health care sector, society in general, and the private sector) had objectives that targeted a certain part of the population, resulting in fractured and disparate policies. Colombia’s new strategy is to reorganize the institutional framework into a single and integrated paradigm.

Alarcón introduced the Early Childhood Commission as a system that includes different sectors, ministries, and entities. She explained that Colombia has one of the greatest degrees of social inequality in the world. According to Alarcón, this new framework is necessary for the protection of the 5 million children experiencing diverse living conditions in Colombia.

A central tenet to Colombia’s current approach is integrated care. Alarcón described the integrated care pathway as a framework that helps to understand the differences in development along the life course from preconception through age 6, as well as how these differences affect policy interventions. This policy framework synthesizes approximately 18 programs moving toward integrated and comprehensive approaches. It provides the structural basis for activities to promote healthy development throughout a child’s life. The development of the integrated care pathway is a complex exercise, with 170 different types of intersectoral activities focused on the child.

Alarcón also defined five lines of action: national management, the development of knowledge, coverage and quality, monitoring and evaluation, and social movement. She referenced two studies on quality. The first study focused on developing a baseline to determine quality in health care services and in child development centers, which includes the quality of information and medical histories for women and children (Centro Nacional de Consultoria, 2013). Research supports the importance of

the prenatal period for pregnant mothers and early infancy. Currently, the medical histories of pregnant women and children are not always recorded or maintained. Colombia has recognized the importance of maintaining medical records, as well as taking actions in measures of quality as it pertains to the health of the developing child; not doing so is counterproductive to the communities being served.

The second study Alarcón referenced is a benefit–cost analysis of the fundamental services at different ages: parenting, feeding, nutrition, vaccines, access to culture, physical and recreational activities, learning, schooling, development, screenings, transitional periods, prevention, recovery, and human rights (Alarcón, 2013). Comparisons can be made between the different types of services and care. For example, the cost of child care for a 1-year-old can range from $800 to $2,600 annually, depending on the setting and services provided. Additionally, the context must be considered, as conditions within a single country can vary. Alarcón noted that the least expensive services are not necessarily the best for the country, as they will have varying levels of impact in different contexts and communities.

Alarcón concluded by explaining that Colombia considers both direct costs such as care for the child and the services they receive, as well as indirect or potentially hidden costs such as social mobilization, communications, training, support, and institutional architectures. When developing a program, both aspects of cost should be considered. In recognition of the diversity within Colombia, including African descendants, indigenous groups, and aboriginal groups, Alarcón emphasized that, even within a single country, one single suite of programs is insufficient. Governments should identify different service modalities and differential costs to best serve the needs of their specific populations.

In response to a question on integrating disabilities into early childhood development, Alarcón noted that Colombia has been able to shift many service modalities to facilitate working with those with disabilities. In line with what Maureen Durkin previously stated, Alarcón indicated that the focus should shift to prevention. A number of disabilities in Colombia are preventable with proper interventions (such as nutritional interventions) during gestation. Alarcón recommended improving training of community health care workers to understand the risk factors associated with nutrition and other preventable behaviors that can lead to child disability.

INVESTING IN YOUNG CHILDREN FOR HIGH RETURNS3

Quentin Wodon discussed three World Bank resources that are being made available to the ECD community and the lessons learned from them:

- A report on trends in ECD investments and lessons from operational work at the World Bank over the past 12 years;

- A guidance document on investing in young children through 25 essential, cost-effective, and high-return interventions for ECD that the World Bank recommends; and

- A summary of some of the progress to date with the ECD module of the Systems Approach for Better Educational Results (SABER), a tool to help conduct comprehensive policy diagnostics in countries, with examples of specific results from of the implementation of the tool in developing countries.

Wodon explained that a number of recent World Bank documents recognize and support the importance of ECD. The Education Sector 2020 strategy (World Bank, 2011) recognizes that the education of children must be supported early to enable future success. The Social Protection 2012 strategy (World Bank, 2012) emphasizes the need to invest in stronger social protection systems to the benefit of children; and recent work on health, nutrition, and population also emphasizes the need for investing in and protecting young children, including in the area of nutrition. In short, the World Bank strategies for human development adopted over the past few years have placed early child development at their core.

Wodon then shared the results from a recent portfolio of ECD interventions at the World Bank (Sayre et al., 2014) that includes an analysis of trends in grants and loans for education, nutrition, and social protection that specifically focus on ECD. The question is whether the higher recognition of the importance of ECD has resulted in more funding for ECD. He observed a sharp increase in operational commitments through grants and loans related to ECD in the past few years, as well as an increase in analytical work on the topic. He noted that while this sharp increase in resources for ECD has been observed only for a few years, it is very encouraging and likely to continue.

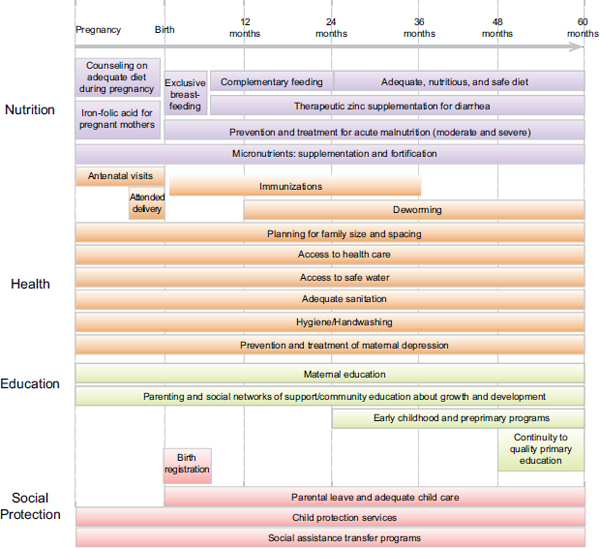

Wodon then identified 25 key cost-effective interventions for young children and families, spanning nutrition, education, and social protection (shown in Figure 9-1). He explained that the World Bank will be releasing a document to elaborate on these key interventions (Denboba et al., 2014). The interventions tend to have high returns, and they can help the

__________________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Quentin Wodon, World Bank.

FIGURE 9-1 Key cost-effective interventions for young children and their families.

SOURCE: Denboba et al., 2014.

discussion and prioritization of ECD initiatives. Wodon was asked which of the 25 listed interventions were the most critical, and his response was that this really depends on the country context in which one operates, but ideally countries are encouraged to implement as many of the interventions as they can. The color scheme in Figure 9-1 refers to the sectors to which the various interventions belong. In addition, although this is not shown in Figure 9-1, the 25 interventions can also be assembled into five integrated packages of interventions and services by age group: a family support package, a pregnancy package, a birth package, a child health and development package, and finally a preschool package.

Wodon then turned to a discussion of a diagnostic tool to help understand the quality of ECD policies in countries. The tool is part of SABER, which helps analyze education systems holistically. The idea of the approach is to complement traditional data on enrollment and learn-

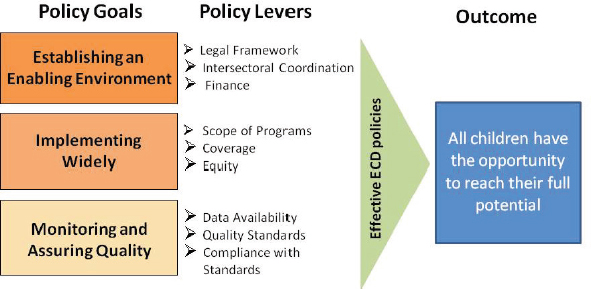

FIGURE 9-2 Policy goals and levers of the SABER ECD framework.

NOTE: An online course introducing SABER ECD as well as other related topics has been developed by Wang et al. (2014).

SOURCE: Neuman and Devercelli, 2013.

ing with an analysis of the policies implemented by countries. SABER includes a dozen modules, one of which is devoted to ECD policies, covering not only education policies for young children, but also policies and programs in health, nutrition, population, and social protection. As with other SABER modules, the SABER ECD module identifies a number of key policy goals and policy levers according to which the diagnostic of policies in a country can be conducted. The goals and levers are shown in Figure 9-2.

The SABER ECD framework helps in assessing whether countries have policies in place that can help ensure all children have the opportunity to reach their full potential. Wodon explained that SABER ECD is being implemented in 50 countries. However, he cautioned that SABER ECD is not necessarily a useful tool for understanding statistically the impact of policies on outcomes—it is rather a tool to help frame a policy dialogue with government ministries, donors, and other stakeholders and to identify areas where a country could do better. The World Bank team is currently working on an analysis of the data collected so far, and the next step will be to assess the extent to which countries are indeed implementing the policies they have adopted.

In concluding, Wodon affirmed that the World Bank is increasing its focus on ECD. He emphasized the importance of identifying cost-effective and high-return interventions (such as the 25 he presented), as well as identifying in a systematic way key policy areas for improvement, with SABER ECD being a useful tool to conduct such a systematic analysis of policy intent and implementation.