4

Organizing Around the Social Determinants of Health

The second panel of the workshop discussed community organizing as a key method for addressing the social determinants of health (e.g., housing, education, wages, and exposure to violence). Recalling the comments by keynote speaker Manuel Pastor on community organizing as an ecosystem, moderator Kate Hess Pace, the lead organizer for the PICO Center for Health Organizing at the PICO National Network,1 said that community organizing has traditionally been fairly siloed in the sense that individual groups tend to focus on individual problems and ignore others, even those that may be connected. However, there is no one program or solution that will fix all of the problems in a community. Hess Pace described the two panelists in this session as being “on the cutting edge” of a new approach to community organizing that focuses on creating relationships and ecosystems for real, transformative change. Marqueece Harris-Dawson, the executive director of Community Coalition of South Los Angeles (CoCo), discussed community building as a key aspect of community organizing for improved health. Phyllis Hill, lead organizer for ISAIAH2 in Minnesota, described her organization’s focus on the links between health, economic security, and equity. As summarized by Hess Pace in the discussion that followed, the process of

____________

1 PICO is a national network of faith-based organizations that is focused on robust community organizing to help people develop a sense of agency to affect the decisions and resources that affect their lives. See http://www.piconetwork.org (accessed August 15, 2014).

2 For more information see http://www.isaiah-mn.org (accessed August 15, 2014).

public engagement and organizing can be as important as the outcome, and projects such as these can influence the health and lives of community members well beyond the original stated goals.

BUILDING COMMUNITY: COMMUNITY COALITION OF SOUTH LOS ANGELES

The focus of community organizing has traditionally been on what he characterized as policy wins, when communities are successful at getting the city involved in addressing problems, said Marqueece Harris-Dawson, the executive director of CoCo.3 As an example, he said that the Community Coalition has learned that in their community a corner liquor store not only contributes to alcohol addiction, but it can also be the site of sex trafficking and illegal drug trafficking, which eventually leads to violence, which often leads to homicide. This one community element leads to the formation of a whole system that supports and encourages behaviors that are deleterious to life and health. In such a situation, the community organizing approach taken by CoCo would be to engage everyone affected by this liquor store (people who live around or drive by the site, children and families that have to walk by it to go to school, and families who have lost members to what is going on at that liquor store) to share their stories and persuade the city to enforce existing laws and also to close the liquor stores. It is relatively easy to evaluate this type of work by enumerating the number of liquor stores closed and to use police department data to show that, for example, within a half-mile radius of every store closed, violent crime calls have decreased by a particular percentage. This type of real data can be used to highlight the organization’s impact and success, Harris-Dawson said.

As discussed by Pastor, over time the focus of community organizing has been shifting toward community building. Community Coalition went through a strategic planning process, and decided to invite members of the community to help them shape future activities. Community members shared their experiences with the organization, and discussed what they would like to see going forward. As expected, Harris-Dawson said, people were very pleased with the elimination of the liquor stores and the associated negative elements. However, what was more important to them than the physical change was the process of creating that change. That process, which included door-to-door campaigning, community meetings, and public hearings, brought the community together. As a result, Community Coalition is now emphasizing the community building aspect as much as the policy aspect. Communities can work

____________

3 For more information see http://www.cocosouthla.org (accessed August 15, 2014).

toward changing their conditions without the permission of the state or the government, Harris-Dawson said. For example, people can decide to park their cars around the liquor store and open a fruit stand in the parking lot, encouraging community members to come by and deter illicit activity.

Harris-Dawson described a campaign to reclaim Martin Luther King, Jr., Park in South Los Angeles. The park was marred by violence because it was surrounded by liquor stores, pawnshops, and motels that rent rooms by the hour specifically to facilitate prostitution. Community Coalition surveyed residents about their perceptions of their neighborhood and found that people felt that the park was by far the most dangerous part of the neighborhood. In fact, many reported that they took circuitous routes home so they did not have to pass by the park, Harris-Dawson said. Although many residents said that they thought there was nothing that could be done, they were still willing to come to meetings.

Bringing activities that appeal to a broad range of people into a public space generally drives out much of the negative activity. With this in mind, Harris-Dawson said, a variety of activities were set up in the park, including a ballet class, a chess league, a video game league, boxing lessons, a Little League baseball team, a basketball league, and a tennis league. Harris-Dawson noted that these are activities that parents pay for in middle-class communities, but they were provided for free to residents at the park. Before the end of summer, the park was completely full at all times of the day with people engaging in activities together. The crime rate, the violence, and the feeling of danger residents had felt decreased dramatically. Importantly, Harris-Dawson said, now that the organizers have stepped back from day-to-day involvement (knocking on doors, going to neighborhood meetings, organizing block parties, and so on), much of the activity continues to go on as people in the neighborhood continue to work together and build their communities. People feel safer, and there is an actual increase in safety and a decline in violent activity, he said. People walk and play where they never could do so before. Most importantly, people understand now that they do not have to accept an undesirable situation and that something can be done about it if they organize together with others who feel the same way. Community building also means helping business owners transform their business into more desirable ventures. Rather than driving the liquor store owner out of business through the force of the state, the community should instead help the owner open a grocery or other business. In closing, Harris-Dawson said that building community is as beneficial as, if not more beneficial than, effecting a change in policy.

COMMUNITY ORGANIZING FOR RACIAL AND HEALTH EQUITY: ISAIAH

Community Organizing

ISAIAH4 is a faith-based, nonprofit organization of 100 congregations in the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul and in outer Greater Minnesota which focuses on racial and economic equity in the state. For ISAIAH, community organizing is “a set of disciplined and strategic practices to build a democratic and collective power to assure the conditions in which communities can thrive” said Phyllis Hill, the lead organizer for ISAIAH. The focus is on extensive leadership development and grassroots leadership as well as on building democratic, accountable, sustainable, community-driven organizations. Hill added that ISAIAH is specifically interested in the links among health, economic security, and equity. ISAIAH’s approach to community organizing, which is similar to that of other organizations, is a cycle of one-on-one relationship building, research, and action (see Figure 4-1). The power to tackle these issues, Hill said, comes from three factors: direct political involvement (e.g., actions, rallies), organizational infrastructure (i.e., building a strong base), and ideology and worldview (the “narrative”).

Integration in Minnesota

In Minnesota, health, education, and wealth indicators show a growing gap between whites and people of color, Hill said.5 Minnesota has historically valued and made progress toward integration, but racial segregation in Minnesota schools persists and is getting worse in many places despite such efforts as choice programs, magnet schools, and integration funding. A school system may be integrated, and there may be a diverse group of people living in proximity to one another in the same town, but the schools themselves can still be segregated—that is, different races can live in different parts of town and therefore go to different schools. Even within a school there can be forms of segregation, Hill said. For example, children of color may not be in the advanced or college prep classes. For

____________

4 For more information see http://www.isaiah-mn.org (accessed August 15, 2014).

5 See, for example, Disparity analysis: A review of disparities between White Minnesotans and other racial groups, prepared for State of Minnesota Council on Black Minnesotans by Jonathan M. Rose, available at http://mn.gov/cobm/pdf/COBM%20-%202013%20Research%20Report%20on%20Disparities.pdf (accessed July 25, 2014), and also http://www.wilder.org/Wilder-Reasearch/Publications/Studies/The%20High%20Quality%20of%20Life%20in%20Minnesota/The%20High%20Quality%20of%20Life%20in%20MMinnesot%20-%20Not%20Equally%20Shared%20by%20All.pdf (accessed July 25, 2014).

FIGURE 4-1 ISAIAH’s approach to community organizing.

SOURCES: Hill presentation, April 10, 2014, and HIP, 2013.

Minnesotans age 18 and under, one in three is a person of color. Fifty-six percent of African Americans and 59 percent of Latino students graduated from high school in 2013, compared to 85 percent of white students. This is one of the largest disparities in the country, Hill noted.

Minnesota has a program called The Choice Is Yours, which is an open-enrollment program that allows inner-city, low-income students to attend suburban schools. In order to participate in open enrollment, students must live in Minneapolis and qualify for the free or reduced-price lunch program. The problem, Hill said, is that choice is limited by access. Families with more financial and transportation resources or more time available outside of work, for example, have more choices than families who do not have these resources. Hill added that because of disparities in income, wealth, employment, and other resources that are correlated with race, access to school choice has become racialized.6

Minnesota has an integration revenue funding stream of about $108 million per year. The funding was intended to help schools with

____________

6 For more information on school choice and racial segregation in Minnesota see http://www.law.umn.edu/uploads/30/c7/30c7d1fd89a6b132c81b36b37a79e9e1/Open-Enrollmentand-Racial-Segregation-Final.pdf (accessed July 25, 2014).

integration efforts, Hill said, but because schools were strapped for funding, it was being used as discretionary money. The state House and Senate decided that since the funding was not being used for its intended purpose and because there was a huge education gap in Minnesota, the money should be repurposed. The state formed a 12-member Integration Revenue Replacement Task Force, which met in 2012 to develop recommendations to improve integration funding mechanisms. ISAIAH and other organizations called for communities of color to be at the table to raise the issues of equity and disparities and to begin to redefine integration, both in the classroom and in society. The ISAIAH Education and Health Committees monitored the process, and ISAIAH decided that a health impact assessment would be an effective tool with which to begin to build the narrative to address the harsh realities of integration and equity in Minnesota.

Rapid Health Impact Assessment of School Integration Strategies in Minnesota

The health impact assessment (HIA), conducted jointly by ISAIAH and Human Impact Partners, focused on the recommendations drafted by the state task force and on the potential health effects of the associated state legislation.7 The process and outcome were equally important, Hill said. The goal was to have a diverse group of people at the table who understood equity, power, and community agency and who would ask questions. Redefining integration and school choice would involve understanding racial wounds, forging new understanding and meaning, and creating a new narrative for integration and opportunity. Hill emphasized that it was essential that the research be co-owned and created by the stakeholders.

The HIA was completed in three months so that the results could be used to inform the legislation that would be based on the state task force’s recommendations. This rapid timeline was possible, in part, because the relationships ISAIAH established over time allowed for timely organization. A 12-member stakeholder panel that convened to guide the HIA included ISAIAH members, teachers, a school district administrator, a school board member, parents, academic researchers, racial justice advocates, and a member of the state Integration Revenue Replacement Task Force. In response to a question, Hill noted that even though there was

____________

7 A health impact assessment is a structured evidence-based process in which a range of factors, including economic, environment, social, political, and psychological are considered in terms of how they impact the health of a population see http://www.ph.ucla.edu/hs/health-impact/whatishia.htm (accessed July 14, 2014).

diversity on the panel, not all groups were represented. For example, there was no one from Minneapolis’s sizable Somali or Hmong populations. Although there are churches among these populations and ISAIAH organizes churches, ISAIAH has not managed to connect with these particular groups, she said. The challenge for ISAIAH now is to develop authentic relationships with organizers in these communities.

Taking a holistic point of view, ISAIAH used the definition of integration developed by civil rights scholar John Powell:

True integration moves beyond desegregation, beyond removing legal barriers and simply placing together students of different races. It means bringing students together under conditions of equality, emphasizing common goals, and de-emphasizing personal competition. True integration in our schools, then, is transformative rather than assimilative. That is, while desegregation assimilates minorities into the mainstream, true integration transforms the mainstream. (Powell, 2005, p. 297)

Hill drew participants’ attention to the last sentence and said that the goal of ISAIAH is to change the narrative and transform the mainstream. She shared several observations about integration from the HIA process. First, the issue of integration is very personal for people, and in some cases people have old or current wounds they have not discussed in public before. Often integration has been defined by a segment of the community that does not include people of color. In Minnesota though there are predominantly white schools, the only schools that are labeled “racially isolated,” are predominantly students of color, Hill said.8

Another issue of much discussion during the HIA was critical race theory. The community challenged the research practitioners to question what they were reading to inform the development of the HIA, why were they reading it, how they were reading it, and whether what they were reading fit in with the community or their personal experiences. These were tension-filled conversations, Hill said, because ISAIAH was challenging the researchers to think in a different way and not to just read standard materials that reinforced the dominant narrative around integration.

HIA Results

The HIA studied the potential impacts of school integration funding on health in two areas: benefits through educational achievement and

____________

8 For the language in the Minnesota Statute on “racially isolated school districts” see the Minnesota Administrative Rules 3535.0110 Definitions. Subpart 7. Available at https://www.revisor.leg.state.mn.us/rules/?id=3535.0110 (accessed July 25, 2014).

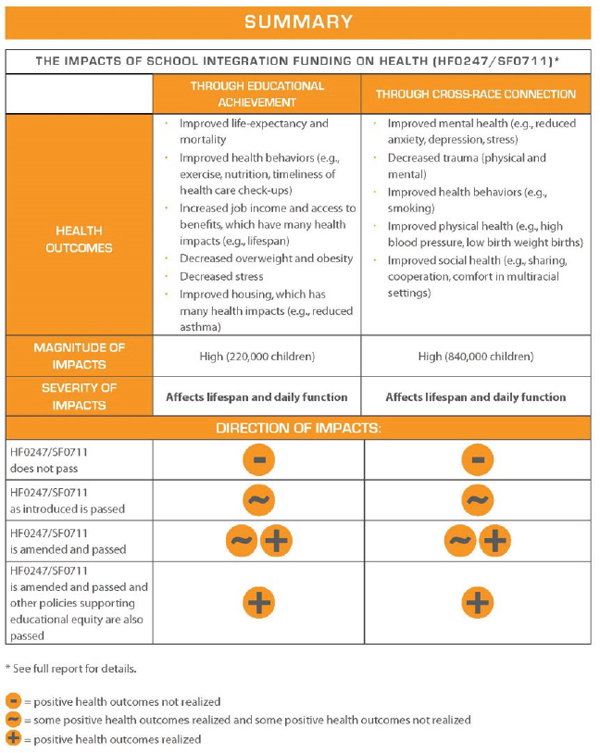

benefits through cross-cultural connections (HIP, 2013), Hill said. The results suggest that supporting school integration leads to improved life expectancy and mortality; improved physical, mental, and social health; improved health behaviors; increased jobs, income, and access to benefits and improved housing; and decreased trauma, stress, and obesity (see Figure 4-2). The overall impact is very positive not just for students, but for the whole state of Minnesota, Hill said.

FIGURE 4-2 Summary of results of the health impact assessment evaluating the health impacts of Minnesota bill HF0247/SF0711 to reauthorize integration funding for schools.

SOURCES: Hill presentation, April 10, 2014, and HIP, 2013.

Outcomes from the HIA include the integration funding reauthorization (the Minnesota Achievement and Integration Program), which was passed as part of the 2013 state budget package.9 Hill noted that the final language in the bill mostly followed or exceeded the recommendations from the HIA. The Minnesota Department of Health provided a report on health equity to the legislature that considered, among other factors, how structural racism is a barrier to achieving health equity for people of color.10 The HIA has also been the impetus for more work to come, Hill said. The commissioners of education and health have initiated a discussion on starting a Health in All Policies initiative, and the Minnesota Department of Health will be conducting an HIA on school discipline policies. A task force is also being assembled to rewrite the desegregation rule because it has been ineffective and there is no incentive for schools to desegregate.

Community organizing may look different in different places, but the goal of all community organizing is bringing people together to build relationships and change the conditions in which they live, summarized moderator Hess Pace. The process of public engagement and organizing is as important as the outcome. Both panelists discussed the importance of building equitable processes that draw people in and create a co-ownership of issues and visions as well as creating space to advocate for change. The examples discussed by the panelists also show how these projects can have broad effects on the health and lives of people in these communities, far beyond their original stated goals.

Access

A participant noted that the narrative around integration is not just about race but about access. Hill concurred and said that housing, for example, is about access to opportunity. In Minneapolis, many people of color live on the North Side. If people want to live together in a community, as a community they need to ask how they can create policies or infrastructure to ensure that some people are not cut off from opportunity (e.g., education, transportation, jobs). In many cases, policy makers do

____________

9 Minnesota House of Representatives, HF 630 Article 3, Sec. 29, Subd. 18. For more information on the program see the Minnesota Department of Education available at http://education.state.mn.us/MDE/SchSup/SchFin/Integ (accessed July 15, 2014).

10 The executive summary, recommendations, definitions of health equity terminology, and full report are available at http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/chs/healthequity (accessed July 15, 2014).

not realize that their policies cut people off from opportunity. This is why Hill and her colleagues encourage policy makers to conduct an HIA or otherwise assess how a policy will affect people of color before making decisions. Integration for the sake of integration may not lead to the best outcome.

Collective Impact

Panelists were asked how their organizations are working across races and cultural groups to achieve collective impact for people from different traditions and with different experiences. Harris-Dawson explained that Community Coalition has been an African-American and Latino organization from the outset because that is the main demographic of South Los Angeles, but there are members of other demographic groups represented in the community, including different Asian populations. He stressed the importance of direct interaction with members of the community, adding that no amount of study or research can replace an actual conversation. Immigrants do not aspire to come to America and open a liquor store in the middle of a violent community. Helping them achieve their goals can coincide with helping the community get to where it wants to be as well. A characteristic that most citizens in Los Angeles have in common is that they are not indigenous; people came to California to live out their dreams and have a good quality of life. Organizers can build unity and campaigns around that theme. Hill said that the congregations that ISAIAH works with are largely African American, white, Latino, or multiracial, and she acknowledged that churches are also racialized. She stated that it is also necessary to have conversations about individual beliefs and faith in order to become a strong organization that can authentically speak about race and integration.

Health Impact Assessments

Many participants discussed the value of the HIA as a tool to help focus on health as part of a bigger issue. Hill noted that it was a public health nurse at ISAIAH who first championed the social determinants of health as a consideration. That same individual is now the assistant commissioner of health and uses her community-organizing skills to organize public health organizations to look at equity and to view the HIA as a tool the community should use. Hill said that there have been many efforts that bring public health and organizing groups together, and these groups have expressed interest in using HIAs to advance their work in Minnesota.

Differing Definitions of Community

A participant pointed out the different uses of the term “community” and the importance of understanding what different groups mean when they use the word. From her perspective as a white person, community is a physical concept that includes school, jobs, social determinants of health, the ability to bike or walk, etc. Conversations with people of color however, revealed that some used community to refer to others of the same race or culture (e.g., all the Latinos in the state). Harris-Dawson agreed that community has different meanings for different people. In some cases, community is used instead of mentioning a particular race because of concerns about singling out a specific group. It is the role of the organizer to define what the term community means at the outset and reinforce it throughout the process, he said.

Finding the “Right” Experts for Partnerships

Participants discussed the role and relationship of traditional experts such as academic partners and public health partners in organizing. Harris-Dawson described three types of experts: scientists who are looking at these projects dispassionately as an experiment; people interested in being around the project and writing about it, but who are not invested in it in any way; and people who are activist experts who want to help with the strategy and be there throughout the process and who are willing to put their names on the work to help advance the agenda. Obviously, he said, people in the third category are the desirable partners.

Hill said that ISAIAH engaged researchers to share, from their point of view, what they thought the main issues were concerning education and health, specifically with regard to equity. It was very important that experts could effectively communicate with and relate to communities of color. Harris-Dawson added that having people, such as professors or health care professionals, tell their stories gives one a sense of their values, where they are coming from, and whether their interest is in making a difference for the community or just doing a study for themselves. The parts of the story they emphasize tell a lot about what is important to them and what type of working relationship an individual is likely to have with them.

Focusing on Health to Improve Education Equity

Hill was asked why ISAIAH chose to frame the integration-in-education issue around health rather than, for example, educational outcomes. She responded that using a health frame—and the HIA tool

in particular—helped to legitimize their concerns by providing credible research and a way for legislatures to engage. The health framework brings people out of their silos and addresses the child holistically. Children enter the classroom with a need to learn, but they may be coming to school hungry or homeless or under a variety of stresses. The health framework widened the conversation about education beyond the classroom.