7

Xinjiang

Zhang Xinshi

VEGETATION AND CLIMATE

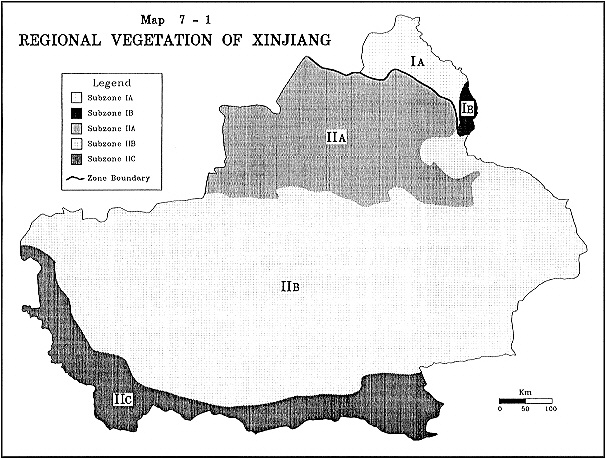

According to the vegetation regionalization of China (ECVC, 1980) and Xinjiang (XIST/IOB, 1978), Xinjiang is divided into two vegetation zones and five subzones (Map 7-1). The northernmost zone (I) in the Altai Mountains lies in a mountainous portion of the Eurasian temperate steppe. It is characterized by montane steppes, coniferous forests, and subalpine-alpine meadows. The desert zone (II) covers the largest part of Xinjiang. It is divided into the cold-temperate desert subzone (IIA), which includes the Junggar Basin and the northern slope of the Tianshan Mountains, and the warm-temperate desert subzone (IIB), which includes the southern slope of the Tianshan Mountains, the eastern Xinjiang Gobi, the Tarim Basin, and the northern slope of the Kunlun Mountains. Vegetation in this subzone is generally sparse and low in productivity. Highly productive vegetation is limited to areas with plentiful water, such as oases, the margins of alluvial fans, and river valleys. The third vegetation subzone (IIC) occupies the eastern Pamir Plateau and northern Tibetan Plateau in southernmost Xinjiang. This subzone is characterized by high-cold desert and desert steppe vegetation. In sum, Xinjiang has diverse

Professor Zhang Xinshi, who spent more than 20 years on the faculty of the August 1st Agricultural College in Urumqi, the capital of Xinjiang, reports on the vegetation and other aspects of the grasslands of China's westernmost region. Professor Zhang describes research on factors that limit the utility of these grasslands and proposes methods for improving grassland management and use.

grasslands, which include deserts, oases, and lowland meadows in the basins; diversified vertical vegetation belts of steppes, meadows, and forests in the mountains; and high-cold desert and steppe on the plateau.

The vertical climatic change in the Altai and Tianshan mountains (Map 1-5) is very prominent. The mean annual temperature in these mountains is between 0° and –5°C, the warmest monthly temperature is less than 15°C, and the coldest monthly temperature is generally below –20°C. The growing season in the Bayinbuluke grasslands lasts for 167 days and the green period for 107 days. Thermal conditions are better in the Ili valley: the mean annual temperature of Korgas reaches 9.6°C, the warmest monthly temperature is 23.5°C, and the coldest monthly temperature is –9.7°C. The growing season for grass in this area is 257 days, and the green period is 221 days. The mean annual temperature in the pediment of the Altai Mountains and the Ertis River valley is 4°C, the growing season for grass is 211 days, and the green period is 178 days. Below a certain altitude—1500–2000 m in most of these mountains, 1100–1600 m in Ili—the winter temperature inversion produces a warm belt that creates fine winter pastures. Mean annual precipitation is generally less than 250 mm in the low-montane desert belt, 250–500 mm in the midmontane steppe belt, and more than 500 mm in the montane forest meadow belt.

The mean annual temperature in the Junggar Basin of northern Xinjiang is 6–7°C. The warmest monthly temperatures in this basin exceed 20°C, and the coldest monthly temperatures are between –12 and –20°C. The annual precipitation is 100–200 mm. With long, cold winters, dry, hot summers, and strong damaging winds, the Junggar supports little good pasture, and conditions are difficult for livestock.

Thermal conditions are better in the Tarim Basin of southern Xinjiang. The mean annual temperature in this basin is 8–14°C; the warmest monthly temperature in most areas is 25°C, although it can reach 32.7°C in the Turpan Depression. The coldest monthly temperature is between –6 and –10°C. The growing season for grass is more than 250 days, and the green period more than 220 days. Precipitation is generally less than 50 mm, and less than 10 mm in Turpan. With so little rainfall the Tarim is dominated by desert grassland, which is of low quality and has low animal carrying capacity (see Table 7-1).

GRASSLAND TYPES AND UTILIZATION

Xinjiang's natural grasslands can be classified by dominant vegetation into four general types and respective subtypes, as follows (XIST/IOB, 1978).

Meadow, the best-quality grassland, accounts for 18.3% of Xinjiang's grasslands and can be divided into three subtypes, according to the topography in which it is found. Mid- and low-montane tall-grass meadow consists of various

Table 7-1 Climatological Indices of Xinjiang

|

Region |

Station |

Altitude (m) |

Mean Annual Temperature |

Minimum Temperature (°C) |

Accumulated Temperature (>10°C) |

Frost-free Days |

Annual Precipitation (mm) |

Aridity Index |

Maximum Snow Accumulation (cm) |

Windy Days > Class 8 |

|

Altai Mts. |

Fuyun |

803 |

1.7 |

-49.8 |

2606 |

122 |

322 |

2.2 |

|

30 |

|

|

Qinhe |

1218 |

-0.2 |

-49.7 |

1978 |

74 |

259 |

2.2 |

|

33 |

|

Junggar Basin |

Changji |

577 |

6.0 |

-38.2 |

3293 |

159 |

183 |

5.6 |

39 |

25 |

|

|

Jinhe |

320 |

7.2 |

-36.4 |

3539 |

179 |

95 |

9.6 |

13 |

34 |

|

|

Qitai |

792 |

4.5 |

-42.6 |

3125 |

155 |

180 |

5.4 |

42 |

19 |

|

North Tianshan Mts. |

Xiaquze |

2160 |

2.0 |

-30.2 |

1171 |

89 |

573 |

1.0 |

|

2 |

|

|

Yunnuzhan |

3539 |

-5.4 |

-33.8 |

0 |

10 |

434 |

|

|

|

|

Ili Valley |

Ining |

770 |

8.2 |

-37.2 |

3219 |

175 |

264 |

4.5 |

69 |

14 |

|

|

Xinyuan |

928 |

7.8 |

-34.7 |

2806 |

163 |

489 |

1.7 |

67 |

14 |

|

Turpan Depression |

Turpan |

30 |

14.0 |

-26.0 |

5455 |

223 |

17 |

60.0 |

|

36 |

|

|

Tokzun |

1 |

14.0 |

|

5338 |

304 |

4 |

|

|

72 |

|

East Xinjiang |

Hami |

738 |

9.9 |

-32.0 |

4073 |

224 |

34 |

29.0 |

|

20 |

|

Tarim Basin |

Kuche |

1900 |

11.5 |

-27.4 |

4330 |

249 |

63 |

12.2 |

|

20 |

|

|

Tieganlik |

846 |

10.6 |

|

4137 |

212 |

25 |

|

|

18 |

|

|

Kashi |

1289 |

11.7 |

-20.5 |

4194 |

222 |

64 |

16.5 |

|

25 |

|

|

Shache |

1231 |

11.3 |

-20.9 |

4080 |

208 |

46 |

24.1 |

|

11 |

|

|

Hetian |

1375 |

12.1 |

-22.8 |

4300 |

230 |

35 |

|

|

8 |

|

Kunlun and Altai Mts. |

Heishan |

2540 |

11.0 |

|

|

|

86 |

|

|

|

|

|

Tiansuihai |

4900 |

-7.7 |

|

|

|

24 |

|

|

|

|

|

Mangyai |

3138 |

1.4 |

|

|

0 |

42 |

|

|

96 |

|

SOURCE: Yang Lipu et al. (1987). |

||||||||||

legumes, grasses, and forbs, and is generally 60–100 cm in height. Yields of fresh grass range between 3.6 and 7.8 tons per hectare and may reach 10 tons per hectare. Meadow provides excellent mowing grass and pasture for large livestock. Alpine-subalpine meadow consists of Kobresia, Carex, Polygonum viviparum, P. songoricum, Phleum alpinum, Festuca rubra, and various alpine forbs. It is generally lower than tall-grass meadow, 10–20 cm in height, and has a fresh grass yield of 1.5–3.0 tons per hectare. Alpine and subalpine meadow provides the best summer pasture. Saline and bog meadows in steppe and desert zones are supported by groundwater or surface runoff. Grasses and forbs consist mainly of Achnatherum splendens, Phragmites communis, Aneurolepidium dasystachys, Aeluropus littoralis, Iris spp., Poacynum Hendersomu, Trachomitum Lancifolium, Alhagi Sparsifolia, and Glycyrrhiza spp. These meadows are 50–80 cm tall and produce fresh yields generally ammounting to 3.0–6.3 tons per hectare. In some cases, yields can reach 10.0–22.5 tons per hectare, but are only 0.75 tons per hectare in heavily saline soil. Saline and bog meadows are also used as summer pasture.

Steppe, which is found mainly in the mountains, accounts for 26.3% of the total grassland area in Xinjiang. Montane steppe consists of Festuca, Stipa, Bothriochloa ischaemum, Cleistogenes thoroldu, Artemisia frigida, Agropyron cristatum, as well as a few legumes and, more often, shrubs. Its fresh yield is generally 0.75–0.9 tons per hectare, and it is used for winter and spring-fall pastures. Meadow steppe contains various forbs, and its fresh yield can reach 1.5–5.25 tons per hectare. Alpine and subalpine (high-cold) steppe occupies the high mountains of southern Xinjiang. It consists of Festuca kryloviana, F. pseudoovina, Stipa subsessiliflora, S. purpurea, Leucopoa olgae, and various alpine forbs. Its fresh yield is 0.6–1.0 tons per hectare. It is used as summer pasture.

Desert grasslands account for 39.2% of the region's total. Desert grasslands are widespread in the basins, reach into the low-and midlevel mountains of southern Xinjiang, and climb to the alpine belt of the Kunlun Mountains. Desert vegetation consists of various superxeric semishrubs (suffruticose), joined by ephemeras in the Junggar Basin and dominated by shrubs in the Tarim. With the exception of Ceratoides and a few other species, desert plants are rough and their quality as forage is low. The fresh yield of desert grasslands is only 0.75–2.0 tons per hectare in northern Xinjiang and 0.3–0.6 tons per hectare in the south. Classified by the texture of their soil substrata, Xinjiang's deserts include loamy desert, gravel (gobi) desert, sandy desert, and saline desert.

Sparse forest and shrublands cover only 2.3% of Xinjiang's grasslands. They consist mainly of Populus euphratica forests and Tamarisk shrublands along desert river valleys and lower margins of alluvial fans, which are usually mixed with grasses of saline meadows. The geographic distribution of grasslands in Xinjiang can be divided into two series: a horizontal (latitude) distribution pattern that includes the Junggar cold-temperate subzone in the north and the

Tarim warm-temperate subzone in the south, and a series of vertical (elevation) distribution patterns for each horizontal zone (XIST/IOB, 1978).

More than 90% of Xinjiang's usable grasslands are grazed on a seasonal basis, so the pastures can also be classified by seasonal type (Table 7-2). Summer pasture, which has the highest animal carrying capacity of the seasonal pastures in Xinjiang, consists mainly of alpine and subalpine meadow, as well as alpine and subalpine steppe, and can be used for 2.5–3.5 months each year (XIST/IOB, 1978). Winter pasture covers a large area, but its carrying capacity is only 60% as high as summer pasture. Winter pasture consists mainly of montane steppe plus some desert and valley meadow, and can be used for 2.5–3.5 months each year. Spring-fall pasture, used for grazing in spring and fall, consists mainly of desert and secondarily of steppe, and can be used for 1.5–2.5 months each year. Summer-fall pasture is widespread in the midmontane and alpine belt of southern Xinjiang and in the Pamir Plateau. It consists mainly of alpine and subalpine steppe, semidesert, and valley meadow, and can be used from mid-May to early November. Winter-spring pasture occupies the desert of the mid-and low-montane belt and piedmont of southern Xinjiang. Year round pasture, located in the fan margin of the Tarim Basin and its river valley, consists of valley meadow, sparse forest, and shrublands.

Table 7-3 gives estimates of the areas, current animal carrying amounts, and potential carrying capacities for each seasonal pasture type. These figures show the imbalance among seasonal pastures in Xinjiang. Summer pastures occupy less than half the area of winter pastures, yet the carrying capacity of summer pastures is 73.7% greater than that of winter pastures. The same can

Table 7-2 Seasonal Pastures in Xinjiang and Their Vegetation Types

|

Mountain System |

Summer (fall) pasture |

Spring-fall pasture |

Winter (spring) pasture |

|

Altai |

Alpine and subalpine meadow, alpine meadow steppe, montane forest meadow, meadow steppe |

Low-montane shrubland steppe |

Low-montane desert steppe |

|

Northern slope of Tianshan |

Alpine and subalpine meadow, subalpine meadow steppe, forest steppe |

Forest steppe, typical steppe |

Typical steppe, desert steppe, desert |

|

Southern slope of Tianshan |

Alpine meadow, subalpine steppe, alpine steppe |

Typical steppe, desert steppe |

Steppe desert, desert |

|

Kunlun |

Alpine and subalpine steppe, desert steppe |

— |

Desert steppe, steppe desert, desert |

|

SOURCE: XIST (1964). |

|||

Table 7-3 Capacities of Seasonal Pastures in Xinjiang

|

Seasonal Pasture |

Area (%) |

Unit Carrying Capacitya |

Potential Carrying Capacityb |

Current Carrying Amountb |

Balanceb |

|

Summer |

13.3 |

0.17 |

36,226.6 |

27,046.3 |

+9,179.8 |

|

Spring-fall |

19.7 |

0.71 |

13,180.3 |

19,126.2 |

-5,945.9 |

|

Winter |

29.1 |

0.67 |

20,856.9 |

21,195.5 |

-339.0 |

|

Summer-fall |

8.3 |

0.92 |

4,302.5 |

3,377.0 |

+925.5 |

|

Winter-spring |

7.3 |

1.47 |

2,369.4 |

2,609.9 |

+234.5 |

|

Spring-fall |

7.0 |

0.97 |

3,385.1 |

10,197.8 |

-6,812.7 |

|

Yearly |

15.3 |

1.36 |

5,414.9 |

11,060.5 |

-5,618.1 |

|

Total |

100.0 |

1.44 |

45,944.0 |

41,483.8 |

-4,460.2 |

|

Balance |

|

|

32,026.3 |

45,057.7 |

-13,031.4 |

|

a Hectares per sheep per year. b 1000 sheep. SOURCES: XIST (1964); XIST/IOB (1978). |

|||||

be said for summer-fall pastures. This shows that Xinjiang lacks winter and spring pastures, and that forage is seriously lacking in both winter and spring.

LIMITING FACTORS

Seven major factors limit the utility of the grasslands in Xinjiang.

Degradation According to XISRD (1989b), Xinjiang has 9.07 million hectares of degraded grasslands, which equals 19% of Xinjiang's total usable grasslands. The chief cause of degradation is overgrazing. Except for some areas of the Altai and Bayingolin Prefecture, most grasslands in Xinjiang are seriously overgrazed. Because of the cultivation, desertification, and secondary salinization that have occurred during the past 30 years, Xinjiang's grasslands have been reduced by 2 million hectares, while the area of degraded grasslands exceeds 13.33 million hectares. The yield of most grasslands has been reduced by 20–70% compared to the 1950s. The carrying capacity of cold-season grasslands declined from 37 million sheep units in the 1950s to 25 million sheep units in the 1980s. About 2 million hectares of desert grasslands have been put under cultivation and more than 0.7 million hectares of grasslands have been abandoned owing to desertification and salinization.

Pests XISRD (1989b) reported that more than 16.67 million hectares of Xinjiang grasslands have been damaged by rodents and other pests. More than 1 million hectares of grassland, or enough to support 9.74 million sheep units, are lost each year as a result of this damage.

Climate Snowstorms, cold temperatures, and lack of precipitation have a serious effect on grasslands. In some years, spring drought prevents leaves from sprouting and causes massive death among livestock (XIST, 1964).

Water According to XIST (1964), the lack of surface water limits the utility of pastures in Xinjiang. The concentration of livestock around drinking water leads to overgrazing and degradation in these areas. According to Xu (1989a), 16.7 million hectares of pastureland in Xinjiang lack sufficient water, forcing livestock to travel great distances once every two to three days, which has the net effect of reducing animal products by 30–50%.

Transportation Because of the lack of roads and bridges, many good pastures have been underutilized or not used at all (XIST, 1964).

Winter-Spring Forage Xu (1989a) points out that owing to the lack of forage, many animals lose weight or die of hunger during the winter and spring. According to Xu, more than 2 million animals die in Xinjiang each year, which is equal to the number of commodity animals purchased in that region during the same period. Weight loss is an even more serious problem: based on a conversion between sheep units and kilograms of body weight, Xu calculates that annual weight loss accounts for four times the sheep lost by death and more than can be made up by the net annual increase in the number of animals. Degradation of winter-spring pastures and reduction of mowing grasslands that provide winter fodder make it difficult to maintain animal production in Xinjiang.

Poisonous Weeds According to Zhang Dianmin (1989), as a result of over-grazing and degradation, poisonous weeds propagate more rapidly, covering large areas of Xinjiang grasslands and threatening grazing animals.

ELEMENTS OF DISEQUILIBRIUM

Xu (1989b) found five elements of disequilibrium in the grassland of Xinjiang.

Animals and Grass The natural grasslands of Xinjiang are insufficient in quantity and quality to support the number and type of grazing animals now in that region. The shortage of winter-spring forage is especially critical. Compared to the carrying capacity of the region's cold-season grasslands, Xinjiang currently has an excess of 13 million sheep units, or 29% of its total animal population (XISRD, 1989a). This explains the high rate of death and weight loss by animals during winter and spring. Not only is grass in short supply, much of it is of poor quality. For example, the nutritional value of the best grass in winter pastures on the northern slope of the Tianshan Mountains

provides only 55–82% of the requirements of sheep that graze there. This means that even under the best conditions, a sheep weighing 50 kg would lose 9 kg during a normal winter and spring.

Water and Grass Some parts of Xinjiang have abundant grasslands but insufficient drinking water, so animals cannot remain in these areas and much of the grass is unused. Other parts have abundant water but insufficient grass; thus herd animals concentrate there, which leads to overgrazing and degradation (XIST, 1964).

Warm-Season and Cold-Season Pastures The theoretical ratio of animal carrying capacities of warm-season to cold-season pastures in Xinjiang is 100:61. However, because of careless management, the effective ratio is now 100:41. This has caused the death and weight loss of animals in winter and spring, and has restricted the development of animal husbandry in Xinjiang (Xu, 1989b).

Inputs and Outputs During the past 30 years, less than 200 million Renminbi (RMB) has been invested in the natural grasslands of Xinjiang. This is an input of only 3 RMB per hectare or 0.10 RMB per hectare per year. By contrast, in 1988 the output value of animal products per hectare of grassland in Xinjiang was more than 60 RMB (Zhang Dianmin, 1989). This suggests a ''plundering'' of grassland resources, which has been the main cause of grassland degradation and environmental degeneration in Xinjiang.

Management Systems The prevailing grassland-animal husbandry system of Xinjiang—extensive nomadism with seasonal migration—has led to high losses of energy, low efficiency of production, lack of support from industry, and failure to establish integrated agriculture-animal husbandry or grazing-fattening management systems. As a result, Xinjiang produces only 10.5 animal product units (APU) per hectare of agricultural and pastureland, compared to 51 APU in the United States or more than 300 APU on some successful fattening farms.

PROPOSALS FOR IMPROVED MANAGEMENT AND USE

XIST (1964), XIST/IOB (1978), Shen and She (1963), and Xu (1989c) have proposed the following methods for improved management and rational use of the grasslands in Xinjiang:

-

Adopt rational planning and conservation approaches. Rational planning for the use of natural grasslands requires that grasslands be divided according to seasonal use and that priority be given winter or winter-spring pastures.

-

Improve grazing systems. (a) Adopt rotational grazing. The animal

-

carrying capacity of Xinjiang could be doubled by applying the method of rotational grazing now practiced in the Tianshan Mountains throughout the region. Under this method of rotational grazing, each sheep needs 0.22 hectare of grassland, whereas in free grazing, each sheep needs 0.63 hectare. The utilization coefficient could be increased by 20–30% and the rate of the animals' weight increase by 10%. (b) Divide herds rationally. Herds should be divided according to species, age, physique, sex, pregnant or lactating females, newborn animals, commodity animals, etc., and the smaller subherds distributed to appropriate pastures. (c) Extend grazing period in summer-fall pastures. By extending the use of summer-fall pastures, the pressure on winter-spring pastures could be reduced. (d) Rationally utilize mowing grasslands and improve methods for making and storing hay.

-

Improve and restore natural grasslands. (a) Improve the water supply of grasslands by storing snow in winter for use in spring, digging wells for springwater and groundwater, and building dams and digging dry wells to store floodwater. (b) Build pastoral roads and bridges for use in remote alpine and subalpine summer pastures or spring-fall pastures on the floodplain. (c) Build livestock sheds to reduce death and weight loss during winter. (d) Irrigate, fertilize, and sow grass. Irrigate plains using floodwater and groundwater. Apply runoff irrigation to clay desert and gravel desert. Irrigate mountain river valleys to establish semiartificial mowing grasslands. Sow appropriate species (e.g., Kochia prostoata) at snow surface on low montane desert and piedmont fans. (e) Eliminate weeds and shrubs. Overgrazing encourages the propagation of poisonous grass and weeds. Damage of this sort can be prevented by regional rotation grazing and appropriate fallow. Shrubs, such as Rosa spp., Spiraea hypericifolia, Caragana spp., and Lonicera microphylla, can harm pastures. Where shrubs are too dense, uprooting or controlled burning can reduce damage. (f) Prevent and control pests. Locusts, marmots, and rodents are three grassland pests in Xinjiang. They occur mainly in overgrazed and degraded grasslands. Pesticides should be used only in grasslands that are already seriously damaged. Generally, these pests can be controlled by the application of rational grazing methods. (g) Control and desalinize grasslands. Salinization, which occurs primarily in desert basins, can be controlled by means of drainage, washing salt, and sowing improved grass seeds.

-

Combine agriculture with animal husbandry and expand use of artificial fodder. (a) Fully utilize agricultural by-products. Each year, the agricultural regions of Xinjiang produce 10 million tons of crop residues and other agricultural by-products, including waste cottonseeds, wheat straw, wheat husk, rice stalk, corn stalk, corncob, sorghum stalk, millet straw, as well as by-products from agricultural processing, such as wheat bran, corn bran, cottonseed cake, linseed cake, rapeseed cake, distiller's grains, fish meal, and bone meal. According to one estimate, the available agricultural by-products could feed 8.4 million sheep units, which is equivalent to 26% of the animal carrying

-

capacity of natural grasslands (Xu, 1989c). (b) Produce artificial fodder. The net yield of available resources can be increased by implementing a dual grass-crop rotation system or triangular grain-economic crop-forage system. The latter system can be created in desert oases by using a ratio of 4:3:3 for the three components and harvesting alfalfa, maize, or juicy fodder for animal feed. Planting and irrigating saline-tolerant grasses along the margins of oases help supplement winter-spring forages. (c) Process forage by means of green storage, alkalinizing, grinding, granulating, and thermal processing to increase the percentage of useful fodder. (d) Use fattening systems in agricultural regions and implement winter commodity fattening systems to increase yields.

-

Shift animal husbandry from mountains to basin oases and combine animal husbandry and agriculture. (a) Zhang Xinshi (1989) has suggested that grassland animal husbandry in Xinjiang should be transferred from the seasonal nomadic pastoral mode in mountainous regions to the settled pastoral-shedded feeding mode and combined with agriculture on the fringe of oases. Zhang offers two reasons for this shift: First, the utilization and development of mountain grasslands in Xinjiang are restricted by topography, climate, transportation, and economic conditions. The rational rotation of pastures is the only means of improving animal husbandry in the mountain grasslands. Second, energy, water, and soil resources are abundant at the fringe of oases. In many such areas, animal husbandry can be combined with agriculture and industry to form an interactive production system. Such a system can provide artificial fodder, forage processing, shed feeding, fattening, and circulation of commodity animals. By adopting rational management of grassland resources, it is possible to reach a carrying capacity of "one sheep per mu" (15 mu equals 1 hectare). (b) Xu (1989c) has proposed the establishment of a grassland agriculture zone. Xu suggests that a system of regional development can be achieved by increasing cultivated farmland, producing artificial fodder, processing animal products, and settling pastoralists.

REFERENCES

Editing Committee for Vegetation of China (ECVC) [Zhongguo zhibei bianji weiyuanhui]. 1980. Zhongguo zhibei [Vegetation of China]. Beijing: Science Press.

Shen Daoqi and She Zhixiang. 1963. Xinjiang de tianran fangmu caochang ji qi liyong [Natural pasture of Xinjiang and its utilization]. Dili [Geography] 3:97–102.

Xinjiang Integrated Survey on Resource Development (XISRD), CAS [Zhongguo kexueyuan Xinjiang ziyuan kaifa zonghe kaochadui]. 1989a. Xinjiang xumuye fazhan yu buju yanjiu [A Study on Development and Layout of Animal Husbandry in Xinjiang]. Beijing: Science Press.

Xinjiang Integrated Survey on Resources Development (XISRD), CAS [Zhongguo kexueyuan Xinjiang ziyuan kaifa zonghe kaochadui]. 1989b. Xinjiang ziyuan kaifa yu shengchan buju [Resource Development and Layout of Production in Xinjiang]. Beijing: Science Press.

Xinjiang Integrated Survey Team (XIST), CAS [Zhongguo kexueyuan Xinjiang zonghe kaochadui]. 1964. Xinjiang xumuye [Animal Husbandry of Xinjiang]. Beijing: Science Press.

Xinjiang Integrated Survey Team (XIST) and Institute of Botany (IOB), CAS [Zhongguo kexueyuan

Xinjiang zonghe kaochadui yu zhiwu yanjiusuo]. 1978. Xinjiang zhibei ji qi liyong [Vegetation of Xinjiang and Its Utilization]. Beijing: Science Press.

Xu Peng. 1989a. Xinjiang caodi shengtai wenti yu duice [Problems of grassland ecology and its strategy in Xinjiang]. Pp. 182–186 in Zhongguo caodi shengtai yanjiu [Research on Chinese Grassland Ecology]. Hohhot: Inner Mongolian People's University Press.

Xu Peng. 1989b. The Resource Characteristics of the Natural Grassland and Its Utilization in Xinjiang (English).

Xu Peng. 1989c. Jiushi niandai beifang caodi shengchan zhanwang [A perspective on production of northern grasslands for the 1990s]. Zhongguo caoyuan xuehui disanci daibiao dahui lunwenji [Collection of Papers from the Third Congress of Chinese Grassland Association]. Beijing: Chinese Grassland Association.

Yang Lipu et al. 1987. Xinjiang zonghe ziran quhua gaiyao [An Outline of Integrated Natural Regionalization in Xinjiang]. Beijing: Science Press.

Zhang Dianmin. 1989. Xinjiang caodi ziyuan liyong xianzhuang, cunzai wenti yu duice [The current utilization, problem of preserving and measures for dealing with the grassland resources of Xinjiang]. Pp. 168–170 in Zhongguo caodi kexue yu caoye fazhan [Grassland Science and Development of Grassland Enterprise in China]. Beijing: Science Press.

Zhang Xinshi (Chang Hsin-shih). 1989. Jianli beifang caodi zhuyao leixing youhua shengtai moshide yanjiu [A research project on optimized ecological models for main types of grasslands in northern China]. Zhongguo guojia ziran kexue jijinhui [Proposal presented to the National Science Foundation of China].