2

Explaining Time Horizons and Technology Investments

The structure that a mature enterprise takes on at any point in time essentially represents the accumulation of a long series of prior resource allocation decisions. Opportunities to invest its limited resources arise continually, in a variety of ways, and must be acted upon by people throughout the organization. Their decisions regarding which opportunities to pursue and which to abandon, which aspects of the organization to strengthen and which to de-emphasize, and how much of their assets to devote to future rather than current needs, ultimately determine the firm's physical assets, human resources, technological capabilities, and overall competitiveness.

—Robert H. Hayes, Steven C. Wheelwright, and Kim B. Clark, Dynamic Manufacturing: Creating the Learning Organization (New York, Free Press, 1988) p. 62.

There is no single or standard definition of the term time horizon and no agreement on what business functions are affected by time horizons that are too short. What is clear is that time, as an element of planning, decision making, and execution, is a crucial aspect of competitive performance in a number of industry sectors. Examples of the role of time in company activities include

-

The time required to commercialize a new product or service that depends on the development and deployment of new technology

-

The planning time frames (operating, business, and strategic) for which a company develops actions it chooses to pursue

-

The time needed to build critical skill bases and teams, or to develop or deploy long-lived assets needed to improve company productivity

-

The expected time between investment in development of a new technology and payoff

-

The time it takes for a new market to develop and become saturated

-

The length of time ahead that an organization can plan because of uncertainties affecting forecasts (procurement cycles, legal changes, or regulatory practices) for the industry

-

The time it takes for a competitor to copy a product and get that product to the market

-

The time scale embedded in the employee incentive and reward system

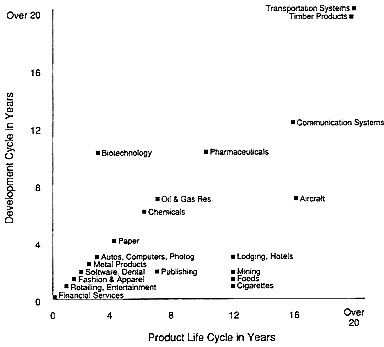

This list makes clear that every corporation operates with a host of different time horizons for its activities; companies must balance a range of different time-dependent business activities. In addition, companies in different industries obviously face different time horizons as a function of different economic, technological, market characteristics, and competitive conditions. Figure 1 shows the variation in company options through the

Figure 1 Typical time horizons by industry. Graph adapted by J. B. Quinn, from a concept introduced in a seminar by W. H. Davidson, University of Southern California, Spring 1986.

wide dispersion, by industry, of both the development times of new products and the market life of products.

The position of different products in Figure 1 shows how two important operational time constants—time to develop and market new products and market life of products—vary by industry. The implication of these variations in industry-specific time cycles is that there will be substantial "natural" variation among industries in many time-dependent business matters. Industry norms for research and development funding levels, development investment per product cycle, plant and equipment investment life, new product pricing strategies, employee reward systems, and competitive strategies are all affected by industry-specific timing factors.

Industry-specific variation in time-dependent business matters illustrates an important point about time horizons: that individual company management and governance practices play a fundamental role in determining time horizons. Companies in industries with long product or market development cycle times—pharmaceuticals or airframes, for example—must have relatively long investment horizons. Stable, successful companies in longer product cycle businesses—and there are many—are proof that effective management can collect and organize financial, human, and technological resources for competitive commercial activities with payback far in the future. This conclusion is buttressed by the fact that, within a given industry, it is possible to find companies with different time horizons and different levels of success. Companies in a single industry face a similar competitive environment, yet some are able to compete much more effectively than others. Such companies have different methods of managing, different time horizons and, consequently it seems, different levels of performance.

WHAT IS “NEAR-TERM ORIENTED” MANAGEMENT AND GOVERNANCE?

Management practices and decisions, in concert with governance structures and practices, play a large role in determining the time horizons that a company exhibits. The willingness and the ability of managers to address the longer-term future of a company are especially critical to a company operating in a technologically dynamic business. The same is true of the demands on a corporate board or on active venture investors; if the governance structure of a company is biased toward short-term return, it will be almost impossible, no matter what the external influences, for the company to develop and deploy new commercial technologies.

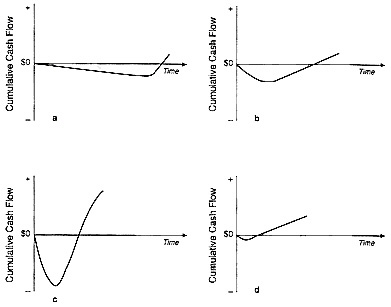

One effective way to characterize management's time horizons relies on time-to-break-even charts (also called return maps—see House and Price, 1991). Time-to-break-even charts show cumulative cash flow plotted over the life of a project. Figure 2 shows hypothetical time plots of the sum of

Figure 2 Graphs illustrate hypothetical cash flows for (a) a project with a long research phase, (b) a typical development project, (c) a major investment in new plant and equipment,and (d) instituting statistical process control in a factory.

forecasted (or actual) expenditures and revenues in carrying out different types of projects:2

-

Figure 2a shows the cash flow of a project involving a protracted period of research—slowly accumulating low-level negative cash flow with a substantial payoff occurring far in the future.

-

Figure 2b shows a prototyping, development, and marketing project with rapidly accumulating initial investment expense and a relatively quickly occurring and high-volume revenue stream.

-

Figure 2c shows the cash flow of an investment in new production equipment—a very expensive investment with rapidly accruing and large cost savings.

-

Figure 2d shows the costs, timing, and returns of instituting statistical process control in a factory—low initial expense bringing on a rapid but small incremental revenue (cost saving).

These figures illustrate a portion of the portfolio of investment options that virtually all companies face; with limited resources for investment in any period of time, a company must make choices among the various options, thereby choosing a mix of expected expenditures and returns. In most cases it is good business practice for managers to establish a balanced portfolio of investments, one that includes cash users and cash generators and both high- and low-risk investments for both the short and the long term.

The range of investment options characterized in Figure 2 can be used to illustrate the arguments that fault U.S. industrial management for being shortsighted. In general, the concept of shortsighted management revolves around a perceived preference (for whatever reason) on the part of corporate managements to invest in activities in which the break-even point occurs relatively quickly after an investment is made. The assertion is that the portfolio of investments that U.S. companies choose is too heavy with those that are likely to yield returns in the near future. The assumption is that U.S. managements are passing up options that are—in some long-term sense—more valuable to the company (and, by implication, to the nation) than the short-horizon projects that companies do pursue.

While we have chosen to illustrate the argument about short-sighted U.S. corporate management using a project analysis and management tool (time-to-break-even graphs), it should be clear that the argument applies broadly to management decisions. For example, a company's management may pay particular attention to operating measures, such as profitability ratios (e.g., return on total assets employed) or activity ratios (e.g., inventory turnover). These tools are primarily useful for comparing an operation's performance relative to others in the same industry or to itself at another time. From the perspective provided by these tools, the short-time horizon argument revolves around whether or not U.S. executives have adequate patience to be competitive. Managers with short time horizons will favor investments in already performing assets (a business line or factory) over assets that may have greater long-term potential but reduce near-term earnings.

In this context, it is easy to see how uncertainty and the related investment risk contribute to shortening time horizons. A project that takes longer to come to fruition is exposed to competitors, faulty cost and schedule estimates, changes in the economic or regulatory environment, or failures in company performance for a longer period of time. The longer an investment takes to develop, the longer it is exposed to the possibility that key personnel, including corporate planners and decision makers, will lose interest, changes jobs, or retire. Referring to a time-to-break-even chart, the longer the expected project profile, the more uncertainty there is about the validity of the forecast of when the curve will turn up, if it will turn up at all, and how fast it will rise. The same logic applies in the case of operating ratios—the longer the

expected time for improvement, the less certain a manager is that the ratios can be made to improve adequately.

Much marketplace uncertainty (and the risk it creates) is the natural countervailing force to long-term planning and investing; decisions that generate a quick, more certain, payoff enjoy a genuine advantage over projects with higher long-term potential but higher risk. A bias in favor of activities with more certain return (often shorter-term investments) is a desirable trait for many managers. Most important, it is a trait that becomes more desirable with increasing uncertainty in the economic and competitive environment. Constantly fluctuating tax or regulatory policy, rapidly changing currency exchange rates, significant uncertainty about market acceptance of a new technology, or a cadre of well-funded, aggressive competitors can all increase the apparent value of a manager who focuses on the immediate future.

THE MECHANICS OF CAPITAL COSTS, RISK, AND THE SPECIAL CHARACTERISTICS OF INVESTMENTS IN TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENTS

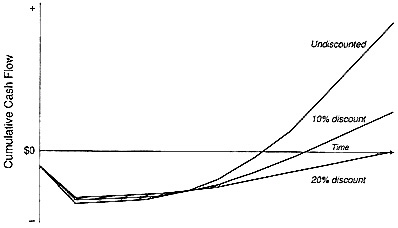

The cost of capital—the required expected return derived from uncertain future cash flows—can dramatically affect the time profile of investment decisions. Although determining the real cost of capital for a company requires a complex estimation based on amounts and handling of debt, equity, and retained earnings (and, depending on the measure, tax and depreciation effects), it is easy to illustrate the impact of more expensive capital on the portfolio of investment options a company faces. Figure 3 shows a time-to-

Figure 3 An estimated time-to-break-even cash flow curve calculated using three different expected rates of return.

break-even cash flow curve calculated using three different expected rates of return on capital: (1) undiscounted cash flow; (2) a 10 percent discount rate; and (3) a 20 percent discount rate. The break-even point shifts further and further into the future with every increase in the cost of capital. This effect applies across the board to all project options and to return calculations on all assets. Therefore, a manager who pays more for funds for investment faces a set of investment options that take more time and risk to produce an adequate return. The higher the cost of capital the more tightly constrained a manager is to select those options with rapid payback.

Perspectives on the Cost of Capital

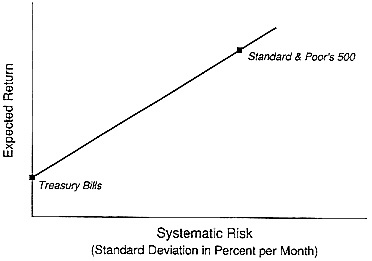

From the perspective of financial investors, the required expected return from an investment is very sensitive to risk. Figure 4 shows a standard model of the increase in return demanded for increasing risk by U.S. financial markets—the capital market line. Any individual financial investment, or

Figure 4 The capital market line. Over the past 65 years, the real return on Treasury bills (generally considered a safe asset) has been 0.5 percent, whereas the arithmetic average of the real rate of return on the Standard and Poors 500 has been 8.8 percent per year. A physical investment (or a human capital investment) whose riskiness is comparable to the Standard and Poor's 500 would have to be competitive on an after-tax basis with the 8.8 percent return on the stock market, not the 0.5 percent return on Treasury bills.

SOURCE: Shoven (1990, p. 5). Reprinted with permission.

portfolio of investments, can be characterized by a point on a plot of return against risk, not necessarily on the capital market line. The mean and standard deviation combinations on this capital market line characterize the demands of the financial market for returns at different levels of risk (Shoven, 1990). The capital market line characterizes and explains the standard definition of the cost of capital as the demands of investors: the required expected return derived from uncertain future cash flows.

An alternative use of the concept of the cost of capital is best described from the perspective of owners and managers of nonfinancial companies who deploy capital. From their perspective the required expected return by investors is the cost of funds. The cost of capital is the pretax rate of return necessary to pay any taxes and the cost of funds. This definition allows decision making on the basis of discounted cash flows or net present value estimates, calculations that discount cash flows by a firm's cost of capital. A related concept is that of an ''investment hurdle rate''—the discount rate that is part of decision-making rules or procedures within a company. The creation of investment hurdle rates often starts with the firm's pretax cost of capital and adds premiums for risk to establish the required expected return on a specific investment or type of investment.

Both the market rate cost of capital and internal investment hurdle rates are important, and they are intimately related. The first definition, which relates to the cost of funds, reflects the financial market's perception of the risk of investing in a company. In large and diversified companies an investor buys a risk/return package that reflects a bundle of company activities, some risky (R&D, for example) and some less risky. The second, as an internal decision-making tool for resource allocation, affects marginal decisions by managers in selection among investment opportunities. For example, should a company spend more on R&D at the expense of upgrading existing plant and equipment? Management decisions—made on the basis of the discounted cash flow projections—will affect the bundle of activities in a company and thereby ultimately affect the company's market cost of capital. Sources of uncertainty (and therefore risk) also affect both types of capital costs.

Although it is widely recognized that risk affects required expected return both within companies and in financial markets, it is less well understood that the character of commercial technological advance poses special problems both for investors (financial markets) and for managers working with investment hurdle rates as a guide in making difficult investment allocation decisions. The demands of developing, deploying, and managing complex product and process technologies create a type of risk that is not necessarily well handled either by financial markets or by managers making investment decisions.

Financial Markets and Technology Investments

With regard to financial markets, the relatively long time periods necessary for technology investments to come to fruition raises the issue of "patient" capital. The point is clearly illustrated by an example of a new company developing and marketing a single product. It is not unusual for product development to take three years, production design two years, and initial market development, concurrent with production tooling and buildup, another two years. It may take an additional five years for the company to show its full potential. In addition, for companies working with newer technology, the ability to react quickly to changes in market demand, consumer preference, and competitor capabilities depends on technical capabilities that usually must be developed and nurtured over a period of several years.

During the substantial time between start-up and a significant revenue stream (the time it takes to prove a product or service in the market) an investment in a technology-based company can be both intangible and highly illiquid. Many investments in technology are intangible in the sense that they are expenditures of funds on learning how a product should be designed or produced, or how a particular market needs to be developed. Such learning investments—in contrast to real estate, capital equipment, or a license to manufacture—are an intangible asset not easily sold or used as collateral.3 As a result an individual investor's exit from a technological venture can be hampered by a very thin market for an interest in an unproven product, and failure (often in the form of bankruptcy) may leave little residual value for any equity investor.

During later stages of a successful new company's growth, an investment becomes more liquid, but an investor who wants to exit may pay a substantial penalty for getting out before the investment is mature. The intangibility and illiquidity of the investment apply to even the most successful technology investments (high annual rates of appreciation if calculated over a long period). In other words, even in technological ventures with good long-term prospects, the characteristics of technological development demand patient capital—investors willing to take their return mostly through long-term appreciation.

The economy has developed a variety of mechanisms to provide patient capital to support new commercial technologies. Financial markets do allow investors with a preference for high-risk, high-potential, long-term payout investments to get access to new, potentially successful technology-based

companies; the technology-oriented segment of the U.S. venture capital industry specifically matches that set of investor preferences to opportunities, and the United States has a highly developed and smoothly functioning high-technology venture capital market. More important, larger, multiproduct corporations allow equity investors to buy a bundle of corporate activities, some of which may be risky new product and market development activities. The fact that technology developments are bundled with less uncertain activities (i.e., existing, successful product lines) provides investors with liquidity and can create a company-specific pool of patient capital for technological risk taking.

Although these mechanisms for providing patient capital do exist, they are not necessarily optimal or even adequate. It is often argued that investor expectations for risk, liquidity, and short-term return from equity holdings in public companies—the cost of publicly traded equity capital—inhibit risk taking, such as technology-oriented, long-horizon investing. It is also true that formal venture capital markets serve only very specialized high-growth-rate opportunities in selected industries; technology-based start-ups can face feast or famine in trying to find venture capital because of relatively thin and uneven investor experience and interest. Finally, some technologically dynamic companies face considerable risk-related problems in simply obtaining loans for growth or modernization. Small companies (under $20 million a year in sales) and technological risk-takers—depending on how their industry is perceived and the state of the economy—may have no effective access to capital despite reasonably good company prospects.

Investment Hurdle Rates and Technology Investments

With regard to investment hurdle rates in management decision making, the primary issues related to technology investments revolve around ways in which management assesses and handles technological or market uncertainty in investment decision making. In the same way that managers and owners make investment decisions with different projected time-to-break-even profiles (see Figure 2), it is also true that managers and owners make simultaneous investments of varying riskiness. As discussed above, these two characteristics of investments—time profile and riskiness—are often correlated, though not perfectly. An investment in developing a new product for a highly competitive market is probably more risky than investing in an upgrade of an existing successful product. The two investments will have different time profiles, different degrees of risk, and can be directly compared, formally or casually, by using a higher investment hurdle rate for the riskier investment.

Table 1 lists factors that will, from the perspective of a manager or owner, increase or decrease the risk of an investment in developing or deploying a new product or process and, as such, affect the appropriate

TABLE 1 Factors that Increase and Decrease Risk Associated with Technology Investments

|

Factors Increasing Risk |

Factors Decreasing Risk |

|

Low experience in the market with the product or service |

Expansion from existing strengths |

|

Strong competitors |

No dominant competitors |

|

Technological uncertainty |

Government technology support or steps to create the market |

|

Environmental uncertainty |

Stable standards—environmental, technological, social, etc. |

|

High potential product liability (medical products, nuclear, toxics, etc.) |

Relevant government infrastructure |

|

Changing standards |

External investment partners (cooperative venture) |

|

Less than strong confidence in internal capabilities |

"Safe harbors" from product liability for certain products (vaccines, defense products, etc.) |

|

Restricted market access, especially in worldwide markets |

Access to foreign or government technology or other external sources |

|

Little protection for intellectual property |

Protection for intellectual property |

investment hurdle rate for the investment. Managers or owners who make resource allocation decisions in technologically dynamic companies are constantly challenged to weigh such uncertainties in investment decision making. Whether or not decision makers formally reduce risk factors to a premium added to an investment hurdle rate, it is obvious that the relevant internal cost of capital (investment hurdle rate) for technology investments is specific to the investment. In this context, it becomes clear that a company's ability to manage and commercialize technology effectively will determine its time horizon for technology investments.

A company that has a deep, reliable competence in commercial development and application of a new technology will take less risk in any particular technological investment than a company that is technologically weak. As a result, a company that is effective at technology management and application will attach a lower-risk premium to a technology investment, allowing it a longer time horizon. Such impacts may be more important to time horizons than economywide conditions such as the average cost of funds or even the marginal cost of funds for a particular firm.

In closing out the discussion of technology investments, it is important to note that the arguments relating technology, management, and investment

do not apply exclusively or even predominantly to new end-user products based on new technologies. The same concerns about investment and time horizons apply to new production technologies and technology-based services, in some cases even more strongly than in new product development cases. For example, some production technologies are "leverage" technologies—crucial sources of production efficiency and competitive advantage but often not a large portion of the cost of end products. Such technologies can be expensive to develop and benefit mostly those companies with substantial long-term presence in the end-product market.

DETERMINANTS OF COMPANY INVESTMENT TIME HORIZONS

As discussed earlier, there is considerable variation in industry-specific time constraints for such things as market life and product development cycle. Some important determinants of time horizons obviously operate for entire industries or industry segments. Prevailing economic conditions—such as the cost of available funds or the rate of growth of consumer purchasing power—or the competitive or product cycle status of the industry can set tight bounds on the options companies can pursue. The legal system can also have a great deal to do with time horizons in an industry. Such is the case in the pharmaceutical industry, where the length of time for drug clearance and patent protection is directly related to return on R&D investment. In yet another set of circumstances, for example when a new market is growing rapidly (where there is significant pent-up demand), the time horizons of companies will be determined less by prevailing economic conditions or legal concerns and more by the speed of competitors.

Another set of important influences on time horizons is highly company-specific and dependent on management and governance decisions. Particularly important is the company's competitive position and trends in the company's market share and profitability; a company that is widely perceived to be losing market share or is less profitable than competitors is likely to focus sharply on the immediate future—the time frame in which its survival will be determined. Additionally, the time horizons of companies are affected by operating routines and practices such as methods of selecting projects, production capabilities, marketing abilities, incentive systems, methods of strategy development, career systems, and methods of raising capital.

Company size and growth rates are also important. For example, small companies and large companies have different needs and limitations with respect to capital availability, capital costs, and sources of new capital. Capital that appears expensive to large companies may simply be unavailable at any price to small companies. The challenges growing companies face also differ from those of mature organizations. Smaller, rapidly growing companies may have greater flexibility in their planning because they lack

the organizational inertia of bigger, more mature organizations. Such companies, however, may also be less stable and therefore relegated to short-term planning aimed at keeping the company in business.

In other words, all companies operate in a complex financial, legal, and competitive environment, and there is clearly no single determinant of corporate investment decision making and planning time horizons.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The common presentation of time horizons in U.S. companies—that U.S. executives are generally near-term oriented and pursue only short-term goals—is too simplistic. The situation with regard to time horizons and technology investments is complex, as time horizons for technology investments should, and do, vary widely by industry, product, and business activity. It is clear that short time horizons are not a universal problem for U.S. companies; there are a number of successful U.S. companies operating in industries that require relatively long time horizons for investments.

Near-term orientation in company behavior can be understood as a preference, subtle or explicit, for a portfolio of investments that are likely to yield returns in the near future. Such preferences are in many cases rational, as technological and marketplace uncertainty, and the investment risk they create, are natural countervailing forces to long-term planning and investing. This link between risk and short time horizons is quite explicit in the role that capital costs and investment hurdle rates play in investment decision making in companies; the more risky the project or venture the more likely it is that both financial markets and internal management decision making processes will require a higher expected return.

The relationship between risk and investment time horizons is particularly important with regard to investments in the development and deployment of new product or process technologies. Investments in technology-dependent ventures may create largely intangible assets, they may be illiquid for long periods of time as projects can be slow to mature, and they are exposed to both normal business risk and technology-related uncertainty. As a result, technology investments often carry a substantial (formal or informal) risk premium. Although some of the risk is irreducible a substantial portion reflects questions about the ability of a company to bring a competitive new product to market or to introduce a substantial process innovation. This implies that short time horizons in technology-dependent investments can be caused by the inability of companies to manage technology effectively; companies with deep and genuine competence in commercial application of technology will have a distinct advantage in adopting longer time horizons for technology investments because they can reduce the risk of their investments.

Important aspects of any company's options, practices, and time horizons are created by a diverse and interactive set of factors, some of which are clearly the prerogative of management and some of which are set external to the company. The specific competitive status of a company, uncertainty, and the abilities of a company's board and executive managers to deal with uncertainty, will affect the time horizon of specific decisions. Also, the expectations of investors (the cost and patience of capital) will interact with the financial structure and investment practices of a company to affect the time horizons of a company's decisions. Finally, the design and implementation of government policy can affect the time horizons of companies. This diversity of influences on corporate time horizons implies that no single actor can unilaterally lengthen investment time horizons. The federal government, boards of directors, and company management will need to act, both separately and together, if U.S. technology investment time horizons are to be lengthened.