3

Company Time Horizons and Technology Investments: The Roles of Corporate Governance and Management

In cases where the unprecedented developments of recent years have contributed to . . . long-term perspectives by motivating managers and financiers to define and implement long-term plans for restoring, maintaining, and improving organizational capabilities, they have helped to make enterprises, industries, and nations more competitive and profitable. But where these developments have encouraged short-term gains—where decisions and actions have been motivated by the desire to obtain high current dividends or profits based solely on the transactions involved in the buying and selling of companies—at the expense of maintaining long-term capabilities and profits, they appear to have reduced and even destroyed capabilities essential to complete profitably in national and international markets.

—Alfred D. Chandler, Jr., Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism (Cambridge, Mass., The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1990), p. 627.

The volume and pace of commercial technological development are increasing in many industries. New products and processes are being introduced more frequently and, from the perspective of an individual company, there are narrower and narrower windows for product introductions. Corporate product development efforts are getting increasingly more sophisticated at surveying and incorporating customer preferences. This pursuit of niche markets demands faster product changes and more flexible marketing departments, design departments, and manufacturing processes. The implication is that organizations must develop and improve their products and

processes with increasing rapidity. Coupled with the immediate need to fix current operational and competitive problems, and the need to meet aggressive financial targets, this can drive managers to focus on the short term. A critical concern for both small and large companies in this situation is the need to excel at product and process renewal, and the development of revolutionary products and processes, without sacrificing the development of long-term organizational competencies.

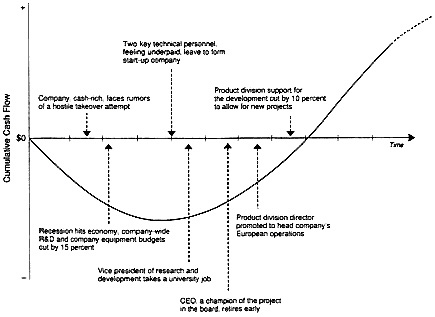

The role of management and corporate governance in effecting successful investment in technology is evident in any examination of typical company operations and can be illustrated with another hypothetical time-to-break-even graph—Figure 5. The vertical arrows indicate common events in the life of a corporation, many of which will directly affect the viability of a technology-intensive project. Most of these events are at least partially under the control of corporate management or a function of governance decisions. A corporation that avoids or manages such events well will exhibit noticeably more constancy of purpose and, probably, longer time horizons than one that does not. The purpose here is not to argue that external influences do not affect corporate time horizons but rather to recognize that management practices can either reinforce or run counter to external influences on time horizons. If the external environment pressures

Figure 5 Hypothetical time-to-break-even graph for a new product development and common events in the life of a corporation.

a company toward inappropriately short-term investment decisions, it is management's responsibility to work against such pressures, to mitigate the impulse to focus too narrowly on short-term accomplishment.

Of course, even the most effective management will not always be successful in overcoming external influences. A company can develop a deeply rooted, short-horizon culture, a culture in which both explicit and implicit criteria for performance evolve to reward and thereby reinforce short-term behavior. For example, a corporation that faces a cost of capital that is high relative to competitors may reward managers who minimize capital equipment, training, and educational investments (longer horizon payback) and who select low-risk, short-term projects. Once this culture is embedded in an organization, even if the real relative cost of capital is significantly reduced, the behavior of personnel in the organization will not change perceptibly in the short term. Employees who have risen in the organization will have done so because it is natural for them to be risk averse and short-term oriented. Even if there are striking changes in the cost of capital, there will not be rapid changes in corporate behavior. This persistence of company behavior in spite of changing external conditions is a familiar phenomenon—one encountered by any manager who has tried to redirect an organization.

Among the factors important to the time horizons of a company's investments and largely under the control of company governance or management are the following:

-

Investment decision-making and planning methods

-

Incentives and reward plans for management

-

Operational and project management techniques

-

Career paths and patterns for employees

-

Corporate financial structure and practices

This section describes major management and governance practices that influence the time horizon a company exhibits. The role of management and corporate governance in capitalization (debt/equity structure, decisions about how and when to raise capital, methods of obtaining investment capital without going to the financial markets) is dealt with only briefly in this section. They are discussed more in Chapter 4, in the context of capital costs.

THE IMPORTANCE OF GOVERNANCE: THE ROLES OF BOARDS OF DIRECTORS

Although the forms of corporate governance structures are circumscribed by law, the variation in practice is substantial. At one end of the spectrum is a small, venture-capital-backed company, the board of directors of which may consist of one or two venture capitalists (representing a pool of inves-

tors), the founder, and a senior manager of the company. In such situations, most investors are intimately involved in, and knowledgeable about, the operation of the company and are either personally interested in its success or directly and immediately responsible to a group of investors. Insiders and outsiders (the venture capitalists) are likely to share a common set of interests as owners; if everyone attends the board meeting, 100 percent of the outstanding equity is well represented at the table.

At the other end of the spectrum are large, public companies with boards of 15 to 20 members or more. With rare exception, no individual director will personally hold more than a few percent of the company's outstanding equity, and most hold much less than 1 percent. The degree to which directors effectively and actively represent shareholder interests is often low. The sheer size and complexity of large public companies mean that, in many cases, inside directors are the only individuals deeply knowledgeable about the company operations. Additionally, financial market structures and practices can minimize meaningful communication between the shareholders and directors. An increasingly important segment of shareholders for large public companies includes institutions (such as pension funds, mutual funds, insurance companies, and trusts) that have professional investment managers who themselves represent others, who often know little about the business the company is in, and who are far more likely to trade out of a company that is performing poorly than to try to improve performance through corporate governance mechanisms. Large-scale, pooled indexed funds are the extreme example as they trade bundles of stocks—each one of which is effectively ignored in buying or selling.

The time horizons a company exhibits are a reflection of corporate goals, directions, and strategies—issues that are the responsibility of corporate governance structures. As such, boards of directors are intimately involved with, and bear substantial responsibility for, directing corporate time horizons. Boards and the top management they select are the people who consistently have access to the type of information that facilitates a high-level, long-term view; they are uniquely responsible for the company's future. Thus, if a public company's performance is weak because of shortsighted investment behavior, it is a failure of its board of directors.

Boards of Directors' Choices and Time Horizons

Ultimately the board of directors is responsible for the time horizons and performance of a company. In many situations this responsibility manifests itself in the board's role in balancing two countervailing financial pressures: the pressure to invest in the activities that secure the survival and future prosperity of the company and the pressure to pay a return to current stockholders. In a technologically dynamic business, where survival and future

prosperity may depend on substantial distant-horizon investment in R&D or new plant and equipment, the balance can be especially difficult to maintain. The same is true in high-growth (often newer technology) sectors where demands for new investment are high relative to industry sales. The ability of a board of directors to work with senior management to negotiate such tensions will play a fundamental role in determining the time horizons and performance of the company.

Unfortunately, few boards of directors of large public companies seem to have the inclination, power, time, or competence to do more than review and approve the proposals of company executive management and the CEO in particular. As long as the proposals are well conceived and in the shareholders' interests, boards of directors appear to perform their functions satisfactorily. However, although they nominally have the authority to exert far more influence than they normally do over company policies, plans, and operations, most boards of directors seem content to advise and consent, reviewing and discussing and, ultimately, approving the propositions that are presented to them by the CEO.

Specifically with regard to time horizons, the board of directors (with the help of senior management) importantly influences the time horizon of a company through the selection and development of senior management. Boards of directors have as a principal responsibility the choice and continued appraisal of the chief executive officers and the development and balancing of senior company management. To be effective at governing a corporation, a board of directors should be attentive to the importance of balance within the senior management team. The following items constitute a short list of concerns about balance in senior management in relation to time horizons: (1) the age distribution of senior management; (2) the degree to which there are high-quality, identifiable champions for the initiatives that should mature into a company's core businesses in the next decade; and (3) the balance between members of the senior management team who are focusing on near-term problems and those who are focusing on the long-term future of the company.

A board of directors is responsible also for designing compensation packages for senior management in a way that is in the best interest of the company. As straightforward as this responsibility appears, it is not uncommon for a board of directors to put together or accept a compensation package that is (1) largely insensitive to corporate profitability or (2) very sensitive to the value of stock prices at the time of retirement or departure (Jensen and Murphy, 1990). Boards of directors should link compensation packages for senior executives to their performance in developing and implementing plans for the long-term prosperity of the company. A compensation package linked to stock price at the time of retirement can provide a strong incentive, depending on the age of the individual and the vesting period, but can also

work against longer time horizons if it provides a senior manager with an incentive to ''cash out'' at the highest short-term stock price without regard to the future of the company.

The actions of boards of directors are crucial to the time horizons of a company and, therefore, so are the methods by which directors are selected, compensated, and removed.

Compensation and Selection of Board Members

The weak performance of some boards of directors in serving the interests of shareholders seems to arise from (1) a lack of information that has not been filtered through the corporate executive office and presented to the board; (2) insufficient time dedicated to reviewing, evaluating, and understanding the information that is available to the board; and (3) insufficient expertise to understand and formulate well-considered opinions based on the information. These common problems of members of boards of directors arise, in part, from the common origins of many directors as sitting or recently retired CEOs, individuals active in public life, or prominent academics. These individuals clearly have deep and useful expertise in many areas, but they may have too little time, incentive, or experience in the relevant industries to be effective board members.

Among the most common suggestions for improving the performance of the boards of large public companies is to provide structures and incentives to drive them to behave more like the boards of well-governed, small, venture-stage companies. In general, this implies that directors need to be more responsive to shareholder interests, less captured by senior company management, and generally more involved in review and resource allocation (Jacobs, 1991; Johnson, 1990; Patton and Baker, 1987). One tool for moving in this direction is the method of compensation for individuals who serve as directors.

Stock ownership valued at several times annual board compensation might better align director's interests with the interests of shareholders; at present, there is no legal requirement for directors to own stock in the corporation on whose boards they sit. Corporations could move to increase the financial stake that their outside directors have in the corporation by requiring that they own shares at least equal in value to a specified multiple of their annual fees as directors. The intent is to link board member compensation as directly as possible to long-term performance in stock price. For new directors, this could be accomplished by paying them only in stock for the first years until the requirement is met. An additional incentive for long-term thinking on the part of directors would be to offer some significant portion of directors' compensation in stock options that can be exercised only after several years.

It is important to note that directors' compensation schemes are not a cure-all for the many perceived ills of boards of directors of public companies. It is easy to argue, given the time commitment and legal exposure of directors, that the vast majority of outside directors of large public companies do not sit on boards because of the compensation. Directors sit on boards for a variety of reasons: as a favor to the chief executive officer, for prestige, to gain experience in another industry, or to gain correlated experience in the same industry. This raises a second issue regarding ways in which directors are selected and removed. Directors and executives in larger U.S. companies tend to come from a common pool of business leaders and as such, it can be argued, best represent the concerns of professional managers rather than investors. One approach for avoiding this situation is for companies to establish a nominating committee of the board consisting entirely of outside directors with sufficient staff support to permit a thorough and competent job to be done.

THE PREROGATIVES OF MANAGEMENT AND CORPORATE TIME HORIZONS

The direction and operation of a corporation is a complex and diverse task often requiring a wide array of managers; companies have top management, sector management, group management, division management, management staffs, functional management, and program management. Some of these managers have immediate-focus, operational positions. Others—usually the more senior management (by whatever title)—have responsibility for strategic direction and significant resource allocation decisions. This section discusses the ways in which senior management affects a company's time horizons. Most of the important roles of senior management with regard to time horizons. can be grouped into three categories: (1) constancy of purpose coupled with flexibility in the development and execution of corporate strategy; (2) design and implementation of career development systems and compensation schemes; and (3) design and choice of decision-making methods and measurement tools. Each of these categories is discussed below.

The Development and Execution of Corporate Strategy

Investment, planning, and operational time horizons are an integral part of strategic planning and execution. An indicator of the degree of which time horizons are adequately treated is the balance of time horizons—from immediate necessary actions, through investments expected to bear fruit in two to five years, to actions expected to ensure the performance of the company five to ten years out. Many companies use a portfolio approach to ensure that there are both long- and short-term projects as well as high- and

low-risk projects. The length of the appropriate set of time horizons is, as noted earlier in this report, dependent on the business sector.

Within this framework, however, managements can vary their mix of long- and short-term projects significantly. Within the same high-technology industry, for example, companies with a basic research strategy will tend to operate with time horizons seven to nine years ahead, surround their discoveries with patents, and use their exclusive positions to increase profits. Others may wait until initial market risks have been taken by others, then move rapidly into the fray. Still others may use a mixed strategy of protecting certain "core lines" of the business with long-term depth and technology, while moving quickly and interactively in other marketplaces using their established distribution capabilities.

Many companies follow such mixed strategies. When they do so explicitly, they may consciously override direct project-by-project present-value comparisons between the different segments of their business and invest in the longer-term segments based on a judgment that these projects will contribute higher payoffs in the long run. The nearer long-term projects move toward the basic research spectrum, the greater this element of subjective judgment must be. A conscious portfolio strategy to defend long-term, uncertain investments in support of specific strategic thrusts can be a rational part of maximizing long-term corporate returns.

Managements are virtually always forced to balance two competing pressures in the execution of a strategy. On the one hand, constancy of purpose in management is important for long-term projects; clearly if top management chooses a strategy for the organization but does not remain firm in its resolve to pursue the goal, managers in the organization will be unable to make appropriate decisions and both the long-term and the short-term health of the company may be jeopardized. On the other hand, management needs constantly to weigh the potentials for a successful outcome from following a given strategy against the potential for losses due to blind pursuit of an elusive goal. The proper use of decision gates—explicitly planned "what if" points at which investment plans are reevaluated—can help management avoid vacillation without incurring unnecessary losses in the execution of strategy for the company.

This tension between constancy and flexibility is primary, but only one of several tensions in which management judgment and execution can make the difference between good performance and failure in management of a technology-intensive business. The following is a partial list of the competing demands, drawn from the personal experience of the committee members:

-

Focusing on products and markets where there is an experience base versus focusing on new technologies or new markets. Focusing on existing products and markets can create a near-term orientation because

-

working on small changes in existing products will pull the time horizons of investment in toward the present.

-

Continuing with a project or development direction versus pursuing a new project or direction. New and untested ideas can look better than a project that is partially completed, especially one that needs management attention to solve critical problems. Management must resist the temptation to switch capriciously to a new and different project or to stay too long with a project that is failing to bear fruit.

-

Incorporating new ideas and information in the execution of a project versus holding to an initial direction. Long-term technology development projects are particularly susceptible to "feature creep"; the continuing accumulation of improvements on the basis of new technical or market information without ever freezing a design. The adoption of some new features may be crucial, but the adoption of too many changes will overburden a project with modifications that escalate its cost and delay its market entry so much that it fails to achieve ultimate success. The trade-off is particularly difficult in rapidly growing new businesses based on rapidly changing technology.

-

Acting on assessments by involved parties versus acting on independent judgment. Project and research directors, responding to company pressures and incentives, routinely underestimate the cost in both time and money to develop new products, produce them, and develop new markets. Underestimating cost and time to payoff on a new technology is a frequent result of combining proponent optimism and real-world uncertainty. Senior managers must establish systems for carefully selecting technology development projects and accurately evaluating their potential benefits, their projected resource needs, and their realistic schedules (and the uncertainties in forecasts of all three).

Because of the special characteristics of ventures or plans that depend heavily on the development or deployment of new technology, senior management needs to understand technology or to seek out advisers (both inside and, frequently, outside the company) who can offer advice and information with respect to technology development and deployment. The consequences of poor management of a longer-term technology-based strategy appear in a host of discernible events—promising projects that are late to market because they are deprived of resources at a crucial time, an increase in the reliance on older products to produce revenues for the company, a difficulty in attracting and keeping good talent because "the action" is elsewhere, a steady decline in investments in longer-term product or production technology development or longer-lived assets, or, the ultimate indicators, steady declines in market share and the exit of patient shareholders.

Unfortunately, the only formula that top management can pursue to ensure success is the continuous exercise of judgment based on analysis and

experience; successful management explicitly plans for the long-term future of a company and manages tensions in execution effectively. Managers intent on, or charged with, developing and deploying technologically new products or processes have to deal with additional uncertainties. In particular, they need to develop and use the ability to assess realistically the uncertainties and time constants of developing technologically new products, processes, and businesses.

Design and Implementation of Career Development Systems and Compensation Schemes

In a nutshell, career systems and compensation schemes may establish procedures or incentives that heavily weight the attention of managers and technical personnel toward the short-term results of segments of the organization rather than on the longer-term results of the company (or business unit) as a whole. Alternatively, such systems and schemes can (1) help focus the attention of management and employees at all levels on the long-term health of the company and the need to make investments in the long-term health and growth of the company; and (2) be an integral part of a company's personnel development efforts—by its very nature a long-term investment.

One crucial relationship between corporate time horizons and careers and compensation exists in the character of job tenure in companies. On the one hand, employees who are promoted too rapidly from one job to another may be encouraged to make overly cautious decisions that may leave their successor with longer-term negative results. On the other hand, they may try to get projects done fast before they move on even if this erodes long-term strength.

Poorly managed turnover can be a substantial barrier to successful technological innovation; turnover, without management attention to the use of deputies or other back-up provisions for key positions, can lead to "start-over." Also, without adequate experience in a position, an individual is not likely to have an appreciation for the fits and starts of commercial technological innovation, a basis for judging the importance, or viability, of a given innovation. On the other hand, significant problems can be created if a company's promotion and career development system leaves managers in certain program or functional positions for too long. Senior management must balance the desire to reward employee performance and to develop talent internally by providing individuals with a variety of experiences against the advantages of longer-term tenure and experience in positions; it is critical to design incentive systems and career paths carefully so that short-term and appropriately long-term performance is rewarded.

Another way in which corporate time horizons are tied to employment practices is through financial incentive systems, which often do not suc-

cessfully match rewards to employee contributions over the necessary time frame for performance. To ameliorate this problem, bonuses can be tied in part to longer-term performance or be at least in part project-related rather than being based solely on current year corporate (or division, or unit) profitability. Obviously, there is no single correct time horizon of reward systems—incentives need to be tied to each employee's specific assignments and, where appropriate, to important time horizons of the division, the industry, and the particular strategy of the company. On the one hand, many managers' primary responsibility is for day-to-day operations and annual incentive systems based on performance against annual operating plans are most appropriate. On the other hand, if a typical new product development cycle is three years with two more years to payoff, the development team bonuses could be partially based on a five-year assessment, and a division director or senior managers' bonus might reflect the average investment-to-payoff cycle. A short-term "fashion" division might get full cash bonuses based on this year's profits. Longer-time horizons for compensation must, of course, be coupled both to the actual time frame of the work and to the employee's ability to affect the performance of the unit or function on which his or her compensation is to be based. Whenever employees are assigned to specific team efforts, part of their incentive compensation should be tied to the success of the team's efforts.

One strong financial incentive for long-range management thinking is equity ownership. To encourage longer time horizons, however, the value of such equity interest must be related to the long-term health of the company. Stock options, with long expiration times (up to ten years) and long vesting times (up to five years) may be a good way to accomplish this. The more of managers' compensation—particularly that of the senior executives—that is in this form, the more likely they will be to take a long-term view of company operations. The intent is that options should extend well beyond foreseeable departures (retirement or promotion to a different position are two common events) to provide an incentive for long-range decision making.

The focus of changes in incentive systems should be to make the reward system robust. The system should use incentives that include, but are not limited to, financial rewards and should also encourage appropriate long-term performance. The incentive system should, in effect, reward understanding of the technological basis of the industry and decision making that is a result of fundamental understanding of the product and the market (Baker et al., 1988; Baker, 1990; and Jensen and Murphy, 1990). One method of accomplishing this may be to design the incentive system of companies to mimic those of new, independent ventures. Additionally, the incentive system could provide financial penalties for poor management decisions.

In summary, senior managers—individuals whose responsibility includes long-term development of the company—need to strive for a balance between

the movement of personnel for talent development purposes and longer assignments to encourage constancy of purpose and longer-term vision within the company. Additionally, bonuses or incentive pay should be based on performance over a period of time that matches the challenges of the position rather than just on the previous year's performance. This is especially important with regard to business projects linked to a technology development and deployment cycle that can take several years to come to fruition. It is also worth considering incentives to encourage longer tenure by key employees who may work on several different projects over time, for example, bonuses that follow an employee from job to job.

Finally, long-range decision making may be encouraged by providing a substantial portion of compensation in stock options for executives who are in a position to influence the long-range performance of a corporation. To be effective, some portion of such options packages should not be exercisable (or vested) for some period of years to encourage appropriate time horizons (the length of time would depend on characteristics in the specific industry).

Decision-Making Methods and Performance Measurement

The method of selecting projects and making funding decisions can determine the time horizon of investment decisions (Baldwin, 1990; Hertenstein 1988, 1990). Analytical decision-making tools that are exclusively finance based, such as discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis, can, if applied blindly, limit the decision maker's exploration of technology issues. These tools, improperly applied, may lead the decision maker to discount future income streams too much; capital budgeting manuals provide ways to ignore cash streams beyond some time, typically three to five years in the future. Common failures in the application of financial decision tools are (1) to ignore unquantifiable characteristics, such as customer satisfaction; (2) to ignore the impact of unpredictable changes—such as competitor's actions—in preparing the analysis; (3) to pay inadequate attention to the assumptions behind the analysis; and (4) to ignore the second-and third-order factors affecting the consequences of a project or program being considered.

If financial analysis tools are poorly understood or sloppily applied, they can lead an analyst to ask the wrong questions. In the worst case, such tools—because they depend on reducing uncertain events to quantified financial outcomes—can create the illusion that a situation is thoroughly understood simply because it can be modeled. DCF and other similar tools, if misapplied, misused, based on faulty assumptions, or used with incorrect data, can result in funding only low-risk, near-term projects.

A common problem in the application of DCF with regard to technology-dependent projects is the tendency to look only at the cash flows represented by the project itself, without considering what will happen if the

project is not undertaken; the value of technological improvements is often based on small net increases in volume or percentage margins relative to current results. On the other hand, technology investments may prevent a loss in market share. The cascading consequences of not pursuing the technological improvement often include the following:

-

Loss of market share

-

Lower production volumes

-

Slower learning curve progress

-

Substantially higher relative costs

The combination of these events can overwhelm the direct effects of the improvement. Conversely, pursuit of improperly evaluated programs based on too optimistic DCF projections have all too frequently led to unnecessary and possibly disastrous dissipation of corporate resources. At a minimum, DCF must give full consideration to the net effects of the investment in relation to the baseline event of not pursuing the project at all.

Technology investments in new projects in many companies are given credit only for the direct effects these projects have on sales volume and profitability. In reality, of course, the shareholder will benefit by some multiple—defined by a stronger price-to-earnings ratio (P/E) of the company—if the project is successful in either an operational or a strategic sense. When looking at acquisitions, these P/E potentials are always considered in the analysis, but they are not part of most internal technology development decisions. Consequently, internal technological developments will tend to be discriminated against in relation to acquisitions of companies that might provide new product lines or product extensions. Comparison of the P/E value of an internal project—no matter how difficult or tenuous the estimation—against the baseline case of not performing the project could change the seeming attractiveness of many longer-term technological projects.

Effective use of financial analysis tools can help establish more appropriate time horizons for projects by estimating the future value of technology investments. However, no analytical tool can solve what is in many cases an organizational problem. Analytical tools such as DCF are only as good as the estimates that are developed as input, often provided by biased parties. Careful analysis of the assumptions behind estimates of expenditures and revenues is an important responsibility of management at all levels. In a similar vein, management is responsible for setting the context for good analysis and decision making; casually selected and promulgated hurdle rates, or target internal rates of return, which are not sensitive to the characteristics of a changing economic environment or of the type of project being considered will create bad decisions. In particular, artificially high hurdle rates will preclude necessary (and appropriate) investment in technology or capital equipment. Finally, developing methods to articulate the benefits and the

risks of developing new capabilities, with their inevitable uncertainties, need to be considered in sensitivity analyses to make full use of such methods.

The issue of measuring corporate performance poses similar problems, though they relate more to assessments by senior management and the board of directors than to decision making within a company. The choice of measures of performance may seem innocuous, but the choice (or choices) drive a variety of decisions and actions taken by members of an organization. Particularly troublesome is the way in which an accepted measure generates actions intended specifically to support the improvement of that measure. For example, top management may choose to focus its attention on profit margin. While profit margins are useful information in some situations, selection of profit margin as an overriding measure of company performance can promote damaging game playing. In most operations it is possible to maintain—or increase—the profit margin by minimizing expenditures for advertising, market development, R&D, or customer-site product testing (or by "creative" inventory valuations, by holding inadequate reserves and by creating windfalls from financial asset manipulation or the sale of assets). Such actions will unquestionably raise the near-term profit margin but may result in limiting the organization's ability to maintain market share and remain profitable in the long run.

In contrast, the selection of market share as the primary measure of organizational performance drives very different actions. Concentrating on market share may encourage decisions to increase capacity, invest in targeting of the product in the market, undertake extensive product development and improvement, and pursue different pricing strategies than those in the profit-as-goal example. These decisions focus on developing and maintaining long-term staying power in the market.

Executives should consider carefully the measures by which they evaluate the performance of the organization. Simple measurements or metrics of performance, by their very nature, can mask what is actually happening; measuring one characteristic of successful competition does not ensure that there is a causal connection between the success of the enterprise and improvement in that metric.

In summary, managers need to guard against the misuse of investment decision-making or modeling tools based on financial indicators. These tools must be examined and revised continuously to ensure that hurdle rates appropriately reflect the company's cost of capital and risk, that appropriate-horizon values are used, and that appropriate termination values are used. Overly narrow analyses of technology-intensive projects or programs are a particular danger; the focus of project and program analyses should be on evaluation of the effect of entire programs on the performance of the corporation, not on individual or incremental projects. Effective use of project analysis tools applied to technology investments requires that the decision to do a

particular project or program be compared with a base scenario of not doing the project or program. The marginal impact of an investment decision should be explicitly compared with the marginal impact of doing nothing. Most important, the analyses should not be restricted solely to financial data—financial analyses should always be supplemented by the use of nonfinancial analyses.

Finally, senior managers should consider carefully the measures selected for examining and reviewing corporate performance. Executives must recognize that the measures used have a significant impact on the decisions that are made and the actions that are taken. In choosing, for example, quarterly profitability instead of market share as a measure of performance, senior management may be promulgating a set of criteria for performance that is not in the long-run interest of the company or the shareholders. Particularly problematic are those measures of performance that do not support the development and maintenance of long-term organizational capabilities in an industry where such capabilities are a requirement for continuing success.

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee concludes that management practices and corporate governance practices and structures must be regarded as important determinants of a company's investment time horizons and its ability to develop and deploy new commercial technologies. This conclusion is supported simply by consideration of the large number of factors under the control of management that affect company time horizons and the degree to which these factors are not well understood or managed in many companies.

The time horizons a company exhibits are a reflection of corporate goals, directions, and strategies—issues that are the responsibility of corporate governance structures. Boards and the top management they select are the people who consistently have access to the type of information that facilitates a high-level, long-term view; they are uniquely responsible for the company's future. Thus, if a public company's performance is weak because of short-sighted investment behavior, it is a failure of its board of directors.

The board of directors importantly influences the time horizon of a company through the selection and development of senior management. To be effective at governing a corporation, a board of directors should (1) be attentive to the importance of balance within the senior management team and (2) link compensation packages for senior executives to their performance in developing and implementing plans for the long-term prosperity of the company.

The committee recommends that a greater portion of the compensation of managers who are in a position to influence the long-range

technological performance of a corporation be granted in stock or stock options. The options should not be exercisable for several years—perhaps five years—and should last for a number of years—perhaps ten years.

Second, since the actions of boards of directors are crucial to the time horizons of a company, so are the methods by which directors are selected, compensated, and removed. Corporate governance might be improved by increasing the financial stake that their outside directors have in the corporation by requiring that they own shares at least equal in value to a specified multiple of their annual fees as directors. The intent is to link board member compensation as directly as possible to long-term performance in stock price, at the same time recognizing that such measures will not be a cureall. Also, because of the special characteristics of ventures or plans that depend heavily on the development or deployment of new technology, board members' understanding the processes of commercial technological innovation is crucial to the execution of their responsibilities.

The committee recommends that corporate boards have nominating committees operating independently of the CEO in choosing new board members and that these nominating committees, in technology-driven companies, give more weight to technological skill as well as business experience in selecting new board members.

The committee recommends that corporations move to increase the financial stake that their directors have in the corporation and that a significant part of director's compensation be paid in stock or stock options.

Third, senior company management plays a very important role with regard to time horizons in at least three ways: (1) constancy of purpose coupled with flexibility in the development and execution of corporate strategy; (2) design and implementation of career development systems and compensation schemes that promote attention to longer-term corporate goals; and (3) design and choice of decision-making methods and measurement tools that suit the demands and uncertainties of technology-dependent investments.

The committee recommends that bonuses paid to managers with scope and authority over long-term performance be based not just on the previous year's performance, but on multiple years' accomplishments.

The committee recommends that companies actively reconsider the way they use investment decision-making tools such as discounted cash flow analysis, especially with regard to decisions involving

new or continuing investments in technology development and deployment. Faulty or unrecognized implicit assumptions, lack of attention to strategic considerations, and poor handling of technological or market uncertainty in the use these tools can critically damage a company's decision making about technology investments.