Appendix A

Cost of Capital—The Managerial Perspective

JOSEPH MORONE AND ALBERT PAULSON

ABSTRACT

This study, prepared for the National Academy of Engineering's Committee on Time Horizons and Technology Investments, examines whether the cost of capital in this country is viewed by senior executives as a source of competitive disadvantage. In particular, it examines the impact of the U.S. cost of capital on managerial decision making. We interviewed 15 senior executives from four capital-intensive industries. Five of the 15 executives (Group 1) argued that the cost of capital has a major impact on their ability to compete, and directly constrains their investments in capital equipment and R&D. Another eight executives (Group 2) expressed a roughly opposite view, arguing that the cost of capital is not one of the primary competitive factors in their businesses. The remaining two executives (Group 3) took an intermediate position.

The differences in views of the impact of the cost of capital on U.S. competitiveness led us to consider two additional questions: how do the Group 1 firms manage this potential source of disadvantage, and what are the possible reasons for the differences in views between Groups 1 and 2? The interviews reveal a rich array of tactics for coping with what the

This study was prepared for the National Academy of Engineering's Committee on Time Horizons and Technology Investments. We are indebted to the committee members, to Kathryn Jackson, NAE fellow and study director, and to Bruce Guile, NAE program director, for the help and support they provided in carrying out the study. We especially wish to thank the executives cited in this study for taking the time to discuss with us their views on the cost of capital. Findings, conclusions, and recommendations of this report do not necessarily reflect opinions or judgments of the committee or the National Academy of Engineering.

A version of this paper appeared in California Management Review 33 (Summer 1991):9-32.

Group 1 executives view as the high U.S. cost of capital. And two factors in particular appear to account for the different views: the firms in Group 2 tend to be in better financial condition than those in Group 1, and are technology leaders in their respective markets.

While there is heated dispute about whether or not the cost of capital in the United States is higher than it is in Japan, there is a growing consensus that Japanese firms behave as if their cost of capital is lower. Moreover, it appears this behavior is deeply rooted in Japan's industrial structure and financial culture, and therefore, is likely to endure. How can U.S.-based firms remain competitive over the long haul against competitors who are able to behave as if they have a lower cost of capital? This analysis suggests that the answer lies in the actions of both individual firms and the federal government that enhance or preserve U.S. technology leadership.

The time horizons of American management have become a subject of widespread concern. A growing body of evidence suggests that the rate of investment by U.S. industry, although it is higher than it has been in the past, is not keeping pace with that of our leading competitors, particularly the Japanese.1 The pattern, if true, is cause for alarm. Over the long run, inability to keep pace in rate of investment results in declines in competitiveness and in turn, in standard of living. But while there is growing concern that U.S. industry's time horizons are shorter than Japan's, there remains widespread debate about the reasons for the difference. The most severe point of contention arises over the cost of capital and its relationship to the problem of time horizons. On the one hand, there are those who argue that the cost of capital in this country is higher than it is in Japan, and that this difference lies at the heart of the time horizons problem. The logic of this argument is as follows: since the cost of capital determines the threshold or ''hurdle" rate of return required to justify an investment financially, the relatively high cost of capital in this country makes investments that are necessary from a competitive point of view difficult if not impossible to justify financially. Further, these investments are being made by our competitors abroad where the cost of capital is lower. Over time, this difference in rates of investment builds into a significant competitive disadvantage for U.S. firms in capital-intensive industries. There remains widespread debate within this school of thought about exactly how large the cost of capital differential is, and about the reasons for the difference, but there is general agreement that reducing the difference substantially would have a major impact on the competitiveness of U.S. industry (Hatsopoulos and Brooks, 1986; and McCauley and Zimmer, 1986).

A second school of thought, which has not received nearly as much prominence as the first, doubts that there is a persistent difference between the U.S. and Japanese costs of capital, and that the reasons that such differ-

ences appear to exist are rooted in difficulties associated with measuring and comparing costs of capital. This view does not deny that there may be important differences between U.S. and Japanese time horizons, but suggests that the explanation for such differences lies less with differences in cost of capital than with differences in the nature of corporate ownership and governance (Abuaf and Carmoy, 1990; and Kester and Luehrman, 1989, 1990b).

This paper is about the cost of capital, but it makes no attempt to resolve the continuing debate about whether or not there is a persistent difference in the U.S. and Japanese costs of capital. Instead, it approaches the subject from a behavioral perspective. We explore not the economic meaning and measurement of the cost of capital, but the way it is perceived by and influences senior executives in a range of American firms. We begin with the following premise: whether or not the cost of capital is lower in Japan than it is in the United States, many Japanese firms appear to approach their investment decision making with longer time horizons than their U.S. counterparts. That is, they behave as if they enjoyed a lower cost of capital (Kester and Luehrman, 1990a). This poses obvious difficulties for their U.S. based competitors. The purpose of this paper is to take a first step toward understanding how senior executives in U.S. firms view this problem and deal with it. In particular, this paper addresses the following questions:

-

Do executives see the U.S. cost of capital as an important source of competitive disadvantage? Does it constrain their making what they believe to be strategically or competitively important investments?

-

If so, how do they balance the conflict between the constraints imposed by the U.S. cost of capital and strategic requirements of their businesses?

-

And, if we find differences among executives in their views on the competitive significance of the U.S. cost of capital, how do we account for those differences?

The answers to these questions are of considerable practical concern regardless of which school of thought proves correct with respect to the cost of capital. Either our Japanese competitors enjoy a lower cost of capital than U.S. firms, or they behave as if they enjoyed a lower cost of capital. The underlying causes for this difference—whichever view is correct—appear to be widely and deeply rooted in the industrial structure and financial culture of the two countries, and while the two systems seem to be converging, substantial differences are likely to persist for a long time to come (see examples in Kester, 1991; Zielinski and Holloway, 1991). Even among those who insist that there is a significant differential in the cost of capital, there is a growing recognition that this differential will not be easily eradicated and that the problem is far more complex than simply a matter of

equalizing interest rates. The differential, they argue, stems from among other factors: differences in capital structures, differences in relationships among firms and between firms and banks, differences in the tax treatment of capital gains and depreciation, differences in accounting practices, and because of the differences in relationships between banks and firms, substantial divergences between published and actual interest rates.2

So whether or not there is a cost of capital difference, the reasons that lead Japanese firms to behave as if they had a lower cost of capital are likely to be with us for a long time to come. Even with trade barriers removed and interest rates equalized, Japanese firms are likely to continue to invest with long time horizons. How to compete effectively against competitors with such long time horizons becomes one of the central issues for U.S. industrial competitiveness.

APPROACH

We examined these questions through interviews with senior executives at 15 firms drawn from four industries. Our criteria for selecting industries were that they be (1) under competitive stress, (2) capital intensive, and (3) relatively diverse. We defined capital intensity broadly, so as to include not just plant- and equipment-intensive industries, but also R&D-intensive and working capital-intensive industries. We attempted to ensure diversity by selecting industries that differed along such broad technology-related dimensions as length of product life cycle, research intensity, and nature of manufacturing process (e.g., chemical process versus component assembly and fabrication). The industries selected in this fashion were machine tools, steel, semiconductors, and pharmaceuticals.

|

Industry |

Life Cycle |

R&D Intensity |

Manufacturing |

|

Machine Tools Steel Pharmaceuticals Semiconductors |

Short Long Long Short |

Low Low High High |

Fabrication/Assembly Process Process Process |

Within each of these industries, we attempted to interview four firms. On the assumption that size might have an important impact on views regarding cost of capital, our goal was to select two relatively large and two relatively small firms for each industry. (Size of a firm was measured relative to other firms in that industry.) Since privately held firms are likely to face very different sorts of financial pressures than publicly held, we limited our sample to the latter. For similar reasons, we excluded firms that had recently been involved in leveraged buy-outs, takeovers, or mergers.3

In total, 15 (of 16) firms agreed to participate:

|

|

Machine Tools |

Steel |

|

Large |

Cincinnati Milacron Cross & Trecker |

Armco Inland Steel Industries |

|

Small |

Hurco Companies |

Nucor Worthington Industries |

|

|

Semiconductors |

Pharmaceuticals |

|

Large |

Intel Texas Instruments |

Merck & Co. Pfizer |

|

Small |

Analog Devices Chips & Technologies |

Amgen Centocor |

THE INTERVIEWS

Question 1: Is the Cost of Capital an Important Source of Competitive Disadvantage?

We approached this question by focusing on specific investments that each firm is reported to have made recently or to be planning. For example, Nucor recently invested $270 million in an innovative and controversial continuous thin-slab cast flat-rolled steel-making facility. (As of 1989, book value of Nucor's assets was $1 billion; sales were $1.3 billion.) In our interview with F. Kenneth Iverson (chairman and CEO of Nucor), we discussed how he viewed the impact of the cost of capital on his decision making for this particular investment. As a consistency check, we then attempted to discuss with each executive two related issues—his or her general decision-making style and his or her view of priorities for government policy.

With regard to decision-making style, we attempted to explore the impact and role of discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis with respect to investment decision making. We expect that virtually all firms engage in this kind of analysis in the course of their investment decision making, just as we expect all firms to be driven by the desire to earn, in the aggregate, rates of return that exceed cost of capital-based hurdle rates of return. The question here is, how heavily is their decision making about specific individual investments governed by such financial analysis as opposed to assessments about overall performance? We would expect decision makers who place heavy weight on the results of such analysis in their decision making about specific investments to be more concerned about the competi-

tive impact of the cost of capital than those who describe themselves as balancing the consideration of strict financial analysis with other, more qualitative factors. In other words, decision-making style can serve as a very rough, second measure of executive views on the cost of capital.

In addition, we asked the executives to identify the most important policy issues affecting their businesses to discover more about their perceptions of cost of capital. We expect that firms that view cost of capital as an important source of competitive disadvantage are more likely than their counterparts to include policies related to interest rates and capital formation among their priorities.

The majority of the responses concerning these executives' views of the cost of capital as a source of competitive disadvantage fall into two general groups. Five executives indicated that it is an important handicap, and that the relatively high cost of capital is an important, if not driving, factor in their decision making. Three of these five executives also indicated that DCF analysis weighs heavily in their investment decisions (the fourth and fifth did not discuss decision-making style explicitly), and four cited interest rates and capital formation as their top or among their top policy concerns.

In a second group, another eight executives expressed a roughly opposite view; they argued that the U.S. cost of capital is not a major source of disadvantage and has not been constraining their investment decision making. These executives point to other factors as more important determinants of their ability to remain competitive. All eight suggested that their decision making about specific investments is tempered by considerations other than strict financial projections of rates of return—which should in no way be taken to suggest that they are not driven to earn overall rates of return that exceed hurdle rates—and six specifically explained that the uncertainties associated with their businesses make financial projections about specific investments too unreliable to serve as the driver for decision making about them. None of the eight stressed interest rates as a critical policy issue, although one did argue that the overall economic environment was an important policy concern.

The remaining two CEOs expressed an intermediate position, arguing that the U.S. cost of capital is not a driving factor in their businesses today, but only because they have taken deliberate steps in the past to avoid becoming capital intensive.

Group 1: Cost of Capital is a Critical Competitive Factor

-

Inland Steel Industries: To Frank W. Luerssen, chairman and CEO, ''managing capital is the name of the game" in the steel industry. Based on his extensive interactions with Inland's Japanese partner (Nippon Steel—

-

see below), Luerssen is convinced that the U.S. cost of capital is substantially higher than Japan's, and that this puts Inland at a distinct disadvantage. The company has just concluded a 20-year assessment of its business and is setting out on a long-term modernization program. The pace at which it invests and the particular investments it makes or forgoes, are directly constrained by hurdle rates determined by this relatively high cost of capital. Inland must "focus our resources on the sure bets," whereas its Japanese partners, given their distinctly (in Luerssen's view) lower cost of capital, "can justify just about anything that comes along."

-

Armco: Robert L. Purdum, chairman, president, and CEO, makes a similar argument. Steel companies operate in a low-growth, low-profitability environment, yet they must continually invest heavily in capital equipment to remain competitive. Compounding the problem is the need to invest in pollution control equipment, which effectively generates negative return on investment. (Purdum does not question the need for such investments, though he does argue for "reasonableness" in environmental policy.) Like Inland, Armco has developed close relations with a Japanese firm (Kawasaki—see below), and like Luerssen, Purdum argues that his Japanese partners operate with far lower costs of capital and therefore are far less constrained in their investment decision making. The higher U.S. cost of capital thus becomes a critical issue, and as with Inland, governs the specific investments that are and are not made. Purdum distinguishes between three sets of investments—those that lead to zero or negative return but are required by government regulation; those that clearly satisfy hurdle rates; and those that are strategically important but that fail to satisfy hurdle rates. It is the third group of investments that are subject to much more review and delay and are pursued only "when we absolutely must," because of the relatively high cost of capital.

-

Texas Instruments (TI): TI is in the semiconductor memory business, which is even more capital intensive than steel. Jerry R. Junkins, chairman, president, and CEO, explained that the average investment required for a new dynamic random access memory (DRAM) manufacturing facility is at least $250 million and will grow to $600 million in the relatively near future. The minimum amount of process-related R&D required to remain competitive, let alone lead, is $100-$200 million per year. TI, based on its own internal studies, concluded that the cost of capital of the U.S. semiconductor industry is roughly 75 percent higher than that of its Japanese counterparts. This leads to a clear and direct disadvantage in a business where success is in large measure determined by ability and willingness to invest. The result is that, like his counterparts in the steel industry, Junkins must continually wrestle with a Hobson's choice: make investments that can be financially justified in the lower cost of capital environment of his competitors, but that do not satisfy his own company's hurdle rates; or forgo such investments

-

and pursue what becomes over the long run "a going-out-of-business strategy." The dilemma becomes acute during industry downturns, since experience demonstrates that to remain viable in an environment with low cost of capital competitors (or with competitors who behave as if they had a low cost of capital), the pace of investment must be maintained.

-

Cincinnati Milacron: James A. D. Geier, chairman of the Executive Committee, views cost of capital as one of several related factors that have led to the demise of the U.S. machine tool industry. Cincinnati Milacron estimates that the Japanese machine tool industry received roughly $11 billion in subsidies from the Japanese government over a 30-year period. An important component of those subsidies was low-cost capital. Conversely, the higher U.S. cost of capital has deterred investment in plant and equipment. "We would be much more modernized [and therefore more competitive] had the cost been lower."

-

Cross & Trecker: The challenge facing Cross & Trecker, at least in the short run, is of a different nature. Its vice chairman and new CEO, Norman Ryker, is restructuring the business and has been focusing his efforts on increasing the company's working capital—a critical issue in a business where orders can take up to a year and a half to complete and where progress payments are more the exception than the rule. To increase working capital, Cross & Trecker recently raised $50 million by issuing preferred stock (10 percent dividends), so Ryker believes he has a very real appreciation of the meaning of high cost of capital. As part of its restructuring, the company is selling some of its businesses and facilities and is not at present investing in new plant and equipment. However, Ryker recognizes that foreign competitors have considerably more modern plants and equipment, and that over the longer term, the company will have to launch a major capital investment campaign. Cost of capital will become an important factor, particularly for "a low-margin industry like machine tools."

As implied in their responses above, three of these five executives expressed a clear orientation toward DCF-type analysis in their decision making. While these analyses do not exclusively govern their decision making, quantitative calculations are emphasized heavily, and appear to be used in these firms to sort out competing investment candidates. This is consistent with the importance that these companies attach to the high cost of capital and their selection of important public policy issues. Luerssen and Junkins cited interest rates and capital formation as their top policy concerns; Purdum cited trade policy, reasonableness of environmental regulations, and policies that would lower the cost of capital, in that order; Geier emphasized overall policy on competitiveness, arguing that policies that influence the cost of capital would follow once the larger problem of competitiveness was confronted; only Ryker did not mention policies that influence capital formation, focusing instead on policies that promote exports.

Group 2: The Cost of Capital Is Not a Major Competitive Factor

Eight other executives offered a strikingly different view of the impact of the U.S. cost of capital on their decision making.

-

Analog Devices, Intel: Ray Stata, chairman and president of Analog Devices and Gordon E. Moore, chairman of Intel, do not feel that their decision making—either with respect to R&D spending or capital investment—is seriously affected by the U.S. cost of capital. Moore argued that time horizons in the U.S. microelectronics industry are unquestionably shorter than those of the Japanese. Nonetheless, he does not believe the cost of capital is at the root of the problem. It is a "second-order effect." "There may be some investments [not made by Intel in the past] that we would have made if the cost of capital had been free, but not many." Rather, in businesses ''where we have to stay in, almost all our investments are made because they are strategically important." Stata stated that while cost of capital is a factor that needs to be taken into account, it is ''at the bottom of the list [of such factors]." Compared to the cost of quality, for example, the cost of capital has a "trivial" impact. Again, investments tend to be driven by strategic requirements.

-

Merck & Co., Pfizer: These two pharmaceutical companies do not view the relative cost of capital as an important competitive factor. For Gerald D. Laubach, president of Pfizer, U.S. health policy has considerably more impact on the competitiveness of pharmaceutical companies than any differences in the cost of capital. Indeed, Judy Lewent, vice president for finance and chief financial officer of Merck & Co., and Francis Spiegel, senior vice president of financial and strategic planning, doubt that there is a persistent, significant difference in the cost of capital for U.S. and Japanese pharmaceutical firms. They conclude that the argument that relative cost of capital is a source of competitive disadvantage "is another myth." Rather, both Merck & Co. and Pfizer believe that their competitiveness is driven by the productivity of their R&D efforts. "The name of the game," to use Laubach's phrase, is to pursue development of a portfolio of new drug candidates through the highly uncertain, R&D-intensive, decade-long new product development cycle. It is the productivity of these R&D efforts, far more than any differences in cost of capital, that determine competitive success. This is not to say that Merck & Co. and Pfizer do not pay a good deal of attention to earning aggregate rates of return that exceed their costs of capital. On the contrary, as Spiegel put it, "we are tremendous slaves to the cost of capital. . . . The hallmark of the corporation is to . . . earn cash flow in excess of your cost of capital." This concern appears to be heightened by the relatively high cost of capital in the pharmaceutical industry, which stems from the high levels of risk associated with new drug development. Nonetheless, Lewent and Spiegel see no incompatibility between high costs

-

of capital and long time horizons. "We don't think strategically in terms of quarters. We think in terms of 5 to 10 years. . . . We don't have much sympathy for people who complain about quarterly pressures. Our mentality and our business drive us to be strategic, but we would be strategic even if we were in a different business."

-

Amgen, Centocor: George B. Rathmann, chairman emeritus of Amgen, and Hubert J. P. Schoemaker, chairman and CEO of Centocor, view the high cost of capital from the perspective of biotechnology start-up companies. The problem of generating capital to fund the long, expensive process of developing new drugs has been a driving concern for these executives ever since the inception of their companies nearly a decade ago. When Schoemaker and his associates began their business, they felt they would need $300 million to $500 million in capital to "become a pharmaceutical company." To date, they have raised $350 million. "Finance is the biggest barrier to entry into the pharmaceutical business." Nonetheless, neither executive views the relative cost of this much needed capital as a major competitive factor. As Rathmann described, "when you are in the creation business, it doesn't really matter whether the cost of capital is 4 percent, 9 percent, or 12 percent. . . . You are pushing for such a big payoff that whether the cost is a few percent higher or lower really doesn't make any difference; it's trivial. I don't spend a second's worth of thought worrying about whether we got the capital at a reasonable rate.'' Indeed, both firms have relied heavily on R&D Limited Partnerships (RDLPs) to fund development of some of their most promising new drug candidates. Investors in RDLPs expect a 40 percent return! As Schoemaker put it, you have to have "a pot of money, or you are not in the game"—whatever the cost of that ''pot."4

-

Nucor and Worthington Industries: Unlike their counterparts at Inland and Armco, neither F. Kenneth Iverson, chairman and CEO of Nucor, nor John H. McConnell, chairman and CEO of Worthington Industries, see the U.S. cost of capital as an important factor in their investment decision making. Iverson argued that aggressive capital spending is a strategic necessity. The company that does not maintain its pace of investment—whatever the differences in cost of capital between U.S. and foreign competitors—falls behind, and once a firm falls behind, it must take on high levels of debt to catch up. In an industry as cyclical as steel, high debt levels eventually lead to serious difficulties. Nucor's rate of investment is constrained not by the cost of capital, but by its overall debt level. It treats a 30 percent debt-to-asset ratio as a ceiling. McConnell likewise emphasized strategic factors in his discussion of Worthington Industries' investment practices. "We try to find the best technology, stay ahead of the competition, and serve the customer. . . . We'll make any investment that will pay back quickly . . . but if it is something that we really see as a must down the road, payback is not going to be that important."

-

Just as this second group differs from the first group on the competitive importance that they attach to the relative cost of capital, so too they appear to be less driven in their decision making about individual investments by DCF analysis, as is illustrated by the following comments:

-

Lewent and Spiegel explained the role of financial analysis in new product development at Merck & Co.: "At the portfolio level [i.e., in the aggregate] we do calculations of return, but it's to make sure we are matching resources to areas where we expect payoffs . . . and to make sure overall return is in line with our expectations for return." But at the individual product level—and development of a successful new product requires on the order of $230 million in R&D, spread over more than a decade5—DCF-style analysis does not become a factor until development is near the point of manufacturing scale-up, and even then it is used not for reaching "go—no go" decisions, but for optimizing the allocation of resources in the scale-up effort. Before that point, given the uncertainties associated with new product development, it would be "lunacy in our business to decide that we know exactly what's going to happen to a product once it gets out." A continuing effort is made to develop and apply financial analysis tools which, rather than govern decision making, can help decision makers deal with the high uncertainties in new drug development in ways that are consistent with "the construct of returning the cost of capital.''

-

George B. Rathmann at Amgen made a similar point. "You cannot really run the numbers, do net present value calculations, because the uncertainties are really gigantic. . . . You decide on a project you want to run, and then you run the numbers [as a reality check on your assumptions]. . . . Success in . . . a business like this is much more dependent on tracking rather than on predicting, much more dependent on seeing results over time, tracking and adjusting and readjusting, much more dynamic, much more flexible."

-

Schoemaker at Centocor works "in zones of gray." He describes his company as being more strategy and event oriented than financial. Even late in the development of a new drug, highly uncertain critical events (e.g., performance of competitive products, results of clinical trials) are such large "swing factors" that future returns simply cannot be reliably projected. Under these circumstances, DCF analysis plays more of a support role than a determinative one, a view echoed at Merck & Co. and Amgen.

-

At Analog Devices and Intel, similar views were expressed. Stata made the point that "particularly in a high-tech business, we do not see how you can play the projecting the numbers game." And Moore, at Intel, argued that "you cannot run a very good model with a situation where prices can fall 90 percent in 9 months. . . . You may run the numbers on the model, but intuitively you worst case it and decide that some things are just too darn risky no matter how the numbers come out. . . . In the businesses

-

where we have to stay in . . . almost all our investments are made because they are strategically important."

-

Referring to the $50-million investment that his company is now making to build a new steel processing plant, McConnell at Worthington Industries said that "from an accounting point of view, our Porter plant is not a good idea. An accountant would say it's not a good idea, from a straight dollar payback perspective. But there are so many intangible benefits that it more than pays for itself."

Likewise, there was considerably less emphasis in this group on interest rates as a critical policy issue. Only Merck & Co. cited economic policy as its primary policy concern. In Spiegel's view, the number one issue is "the common enemy . . . the enormous and increasing U.S. national debt." For the three other pharmaceutical companies, policies influencing the "tail end" of the innovation cycle—policies affecting the reimbursement of medical costs and the pricing of prescription drugs, protection of intellectual property, and delays in the issuance of patents and Food and Drug Administration approvals—are of greatest concern. Merck & Co. also believes these are important issues, and its emphasis on the national debt stems in large measure from a concern about the impact of that debt, and efforts to reduce it, on the nation's health policy and health care system.

As for the semiconductor firms in this second group, both Intel and Analog Devices cited R&D policy as critical. Moore (Intel) also emphasized trade policy, while Stata (Analog Devices) argued that there was much more that the federal government could do to promote learning among firms. For example, he cited the problem of quality, and how in the absence of a mechanism for learning across firms, many firms are forced to work through the same problems and mistakes. Nucor and Worthington Industries, meanwhile, mentioned none of these issues and instead suggested that for the steel industry, the costs of environmental regulation—or more precisely, the pursuit of "reasonable" requirements—was most important.

Group 3: The Mixed View

Hurco Companies and Chips & Technologies took an intermediate view on the impact of cost of capital on their businesses.

-

Hurco Companies: Brian D. McLaughlin, CEO, argued that for a small machine tool company like Hurco Companies, which faces competition from the likes of the Fanuc-GE joint venture, Mitsubishi, and Siemens, the key to remaining competitive is to avoid competing on a capital-intensive basis (i.e., on the manufacturing of mechanical and microelectronic hardware) and to focus instead on staying ahead in controls, user interfaces, and application

-

software. Hurco Companies thinks of the machine tool as "a shipping crate" for its software and controls. This suggests that cost of capital is not a driving force in this business. On the other hand, the very logic of avoiding the capital-intensive aspects of the machine tool business suggests a fundamental concern about availability and cost of capital. And in two other respects, McLaughlin was quite explicit about the impact of the cost of capital on his business. First, while Hurco Companies is financially sound today, it was in deep financial difficulties in the mid-1980s. Then, the cost of capital was a dominant concern. Second, to the extent that a high cost of capital dampens the climate for investment in manufacturing plant and equipment in this country, it has a direct impact on Hurco Companies. This is why McLaughlin's priority for federal policy is to strengthen the overall economic environment, beginning with a lowering of interest rates. His second policy priority is to strengthen, in part through technology policies, the manufacturing base of the country.

-

Chips & Technologies: Gordon A. Campbell, chairman, president, and CEO, reported that while the cost of capital is a concern, it is not one of the top factors constraining his business. "We know the type of products we need; we know the time frame in which we need to develop them; . . . we have a roadmap. I can't blame that [failure to realize those plans] on the cost of capital." On the other hand, the reason the cost of capital is not a critical issue for Chips & Technologies is that the firm very deliberately set out to avoid capital intensiveness. When Chips & Technologies was starting up, the only way to raise enough capital to build its own fabrication facilities would have been "to give away 80 percent of the company." So the general approach became to "do anything you can to avoid becoming capital intensive.'' Just as Hurco Companies views the machine tool as a "shipping crate," Chips & Technologies views semiconductor fabrication capability as "a commodity." Its devices are now fabricated at about a dozen foundries worldwide. From a policy perspective, Campbell was much more concerned about the general problem of a lack of a cohesive policy regarding the competitiveness of U.S. industry than specifically about interest rates or policies affecting capital formation.

Table A.1 summarizes the responses of the three groups of executives to the first question in the interview: Is the cost of capital an important source of competitive disadvantage?

Question 2: How Do the Firms that Emphasize the Competitive Impact of the Cost of Capital Manage the Problem?

The interviews show that U.S. companies are employing an array of tactics for managing the conflict between the constraining effects of the

TABLE A.1 Summary of Responses

|

|

Cost of Capital an Important Competitive Factor? |

Emphasis on DCF in Decision Making for Specific Investments? |

Policy? |

|

Group 1 |

|||

|

Texas Instruments |

Yes |

Yes; less than in past |

Capital formation |

|

Armco |

Yes |

Yes; basis for screening |

Trade, environmental, interest rates |

|

Inland |

Yes |

Yes; basis for screening |

Interest rates |

|

Cincinnati Milacron |

Yes |

Not discussed |

Competitiveness |

|

Cross & Trecker |

Yes |

Not discussed |

Export policies |

|

Group 2 |

|||

|

Analog Devices |

No |

No; uncertainty, strategic |

R&D policy, learning |

|

Intel |

No |

No; uncertainty, strategic |

R&D, trade policy |

|

Merck |

No |

No; uncertainty, strategic |

National debt, health policy |

|

Amgen |

No |

No; uncertainty, strategic |

Health policy, patents |

|

Centocor |

No |

No; strategic factors |

Health policy, patents |

|

Nucor |

No |

No; strategic factors |

Environmental |

|

Worthington |

No |

No; strategic factors |

Environmental |

|

Group 3 |

|||

|

Hurco |

Indirectly |

Not discussed |

Economy, manufacturing |

|

Chips & Technologies |

Indirectly |

Yes for incremental steps, no for more radical steps |

Competitiveness |

cost of capital and the strategic necessity for continuing investments. The behavior of these companies suggests that the relative cost of capital is not a fixed constraint but a condition that is at least partially manageable.

Texas Instruments, as it struggles to regain leadership in the capital intensive DRAM business, has taken a variety of steps that in Junkins' words, "simulate access to a low cost of capital environment." For example, TI has entered into a series of joint ventures that have in effect made an additional $1 billion available to the company over the next several years.

-

In an agreement with the Italian government, TI will invest $500 million over four years to expand its Italian operations. The expansion will include a 4-megabit DRAM manufacturing facility, a new applications research center, and upgrades of existing facilities. The Italian government will contribute nearly $700 million in cash, tax incentives, low-interest loans, and infrastructure improvements (see, for example, Wall Street Journal, November 8, 1989, p. A4).

-

In an agreement with Acer of Taiwan, Acer will contribute 75 percent of the capital required to build and operate a $250-million DRAM facility. TI will contribute 25 percent plus technology, and will receive all the output of the facility. Acer has the option to purchase up to 50 percent of the output.

-

In an agreement with Kobe Steel, Kobe will contribute most of the $350 million required to build a facility that will produce logic and application-specific devices. TI will sell all the output of the plant under its name, even though it is the junior partner in the joint venture.

Other steps taken by TI to lower its cost of capital include sale-leasebacks and conversion of preferred stock; aggressive prosecution of patent violators, which has generated a significant new stream of income estimated to exceed $200 million per year; and efforts to develop a modular approach to semiconductor manufacturing, which if successful, would reduce the required "capital investment by an order of magnitude." At the same time, TI has been investing aggressively in new capacity. In 1990 alone, during what has proved to be a significant downturn in the semiconductor business, it has continued to accelerate its pace of investment, which has been "tearing heck out of the bottom line." But given TI's commitment to remain competitive in the DRAM business, Junkins does not believe TI can afford to cut back on investment during the downturn. Investing through the downturn is thus another way in which TI is responding to the strategic requirement to invest in an environment of high capital costs.

In the steel industry, Armco and Inland Steel Industries have engaged in a not dissimilar set of tactics. Perhaps the most dramatic example is a series of agreements between Inland and Nippon Steel, agreements that have grown into a $1-billion joint venture to build and operate two world-class steel-making facilities—one that manufacturers cold-rolled sheet-steel products and the other that produces coated steel products. The first of the two facilities, which is now in operation, is achieving "unprecedented" productivity and quality. Inland owns 60 percent of the joint venture. As calibration of the magnitude of the effort, the first of the two plants accounts for roughly 20 percent of Inland's total steel production. But what is most significant about the joint venture is how it was financed. It is not carried on Inland's books; the financing for the joint venture is backed solely by the assets of the joint venture itself. Twenty percent of Inland's investment

is equity based; the remaining 80 percent is funded through debt by a Japanese institution. Luerssen reports that the interest rate is lower than the rates available from U.S. banks, although higher than the rate available in Japan. More significant than the rate is the capital structure agreed to by the Japanese bank—20 percent equity, 80 percent debt—and the non-recourse financing. The "capital structure of the joint venture looks like that of a Japanese firm." Otherwise, "we never could have gone ahead with the deal."

Armco has taken similar measures. It has entered into several joint ventures, the most dramatic being a joint venture with Kawasaki Steel Company, into which Armco has spun off its carbon steel facilities, which represent about 40 percent of its total capacity. Kawasaki in turn, is investing $500 million in the joint venture, and as 50 percent partner, is assuming half the obligations associated with the spun off facilities as well. Armco projects a need for $1.5 billion in investment in the joint venture, which will be raised by the joint venture itself, not Armco. Like the Inland-Nippon joint venture, the Armco-Kawasaki joint venture is off Armco's books and has access to Japanese financing, which translates to somewhat lower rates but more importantly to a very different and more highly leveraged capital structure.

Apart from these measures for gaining access to foreign capital, the most important other tactic for managing the cost of capital employed in our sample was exhibited by the two smaller firms in Group 3. Both Hurco Companies and Chips & Technologies have devised strategies for competing in their industries without heavy capital investment. Neither manufactures hardware or electronic components for their hardware, thereby greatly reducing their vulnerability to the cost of capital. At Chips & Technologies, "our whole strategy is to avoid capital intensiveness."

Question 3: What Accounts for the Differences in Views on the Cost of Capital?

How do we account for the differences in the executives' views on the competitive impact of the cost of capital? Why do Group 1 executives see it as an important source of competitive disadvantage, while Group 2 executives emphasize other variables—such as quality, ability to stay ahead in process technology, ability to develop new drugs—as weighing more heavily on their ability to compete than possible differences in the cost of capital?

Notice first of all that both views are compatible with economic theory. Group 1 executives argue that they face a competitive disadvantage because given what they see as a relatively high cost of capital, they have difficulty financially justifying investments that their competitors would not have difficulty justifying. But this in no way implies that Group 2 executives are any less concerned about achieving financially justified rates of return than Group 1 executives. They are no less aware of the relationship between the

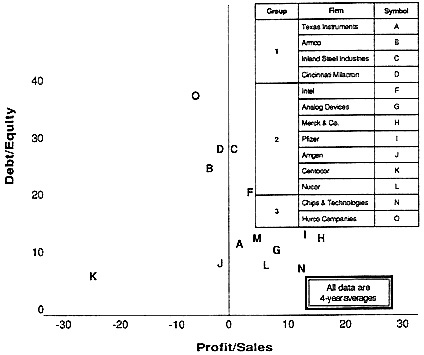

Figure A.1 Profitability versus indebtedness (4-year average, 1986-1989).

cost of capital and the economic definition of acceptable returns. They are as likely to calculate the rate of return of potential investments, even if they are not as driven by the results of such calculations in their decision making about specific investments. And if actual returns are any measure of intent, the firms in Group 2 have tended over time to be more profitable than the firms in Group 1. The Group 2 firms in the steel and semiconductor industries have been more profitable than their Group 1 counterparts (see Figure A.1).

In short, it is not plausible to argue that the difference in views about the competitive impact of the cost of capital is due to difference in rationality or concern about shareholder interests. How then do we account for the difference? Why do some executives view the relative cost of capital as fundamental to their ability to compete, and others not?

Industry Type

One possible explanation is that the cost of capital varies from industry to industry, and that in some industries, the difference between U.S. and

TABLE A.2 Responses by Industry

|

|

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

Group 3 |

|

Machine Tools |

Cincinnati Milacron Cross & Trecker |

|

|

|

Steel |

Armco Inland |

|

Nucor Worthington |

|

Semiconductors |

Texas Instruments |

Analog Devices Intel |

Chips & Technologies |

|

Pharmaceuticals |

|

Amgen Centocor Merck Pfizer |

|

Japanese costs of capital are substantially greater than in others. For example, Merck & Co. (Group 2) doubts that there is a persistent difference in the cost of capital between the United States and Japan, whereas TI (Group 1) estimates that for its industry, the U.S. cost of capital is 75 percent higher than Japan's. Perhaps the different responses simply reflect inter-industry differences in relative cost of capital. This explanation is appealing in its simplicity, but unfortunately, it is only partially supported by the interviews (see Table A.2). All the executives from the pharmaceutical industry believe that differences in the cost of capital are not a critical issue, whereas all the executives from the machine tool industry take the reverse point of view (although Hurco Companies' point of view is a bit more complicated). On the other hand, within the semiconductor and steel industries, different executives expressed different views. This suggests that even if there are inter-industry differences in the relative cost of capital, these differences do not fully account for the differences in opinion about the competitive importance of the relative cost of capital.

Size

Originally, we expected that company size would be related to views about the competitive significance of the cost of capital, since small, growing firms often face the need for more capital than their limited cash flow can provide. But at least in this sample, if there is any relationship between size and views on the cost of capital, it is exactly the opposite of what we had expected (see Table A.3). There are no small firms in Group 1. However, both Group 3 firms—that is, firms that took an intermediate position

TABLE A.3 Responses by Firm Size

|

|

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

Group 3 |

|

Large: |

Texas Instruments Armco Inland Cincinnati Milacron Cross & Trecker |

Intel Merck Pfizer |

|

|

Small: |

|

Analog Devices Nucor Worthington Amgen Centocor |

Chips & Technologies Hurco |

on this question—are small, and while Cincinnati Milacron and Cross & Trecker are large relative to U.S. machine tool makers, they are small in comparison with the other large firms in this sample. If we consider them small firms, the pattern begins to seem unrelated to size. Both large firms and small firms express both points of view with respect to the competitive effects of the cost of capital.

The responses of the three relatively young companies in our survey—Amgen, Centocor, and Chips & Technologies—are especially interesting. On the one hand, Chips & Technologies has built its entire business strategy around its desire to avoid the constraints imposed by the cost of capital. On the other hand, for the two biotechnology firms, the cost of capital was not nearly as important as its availability, as is reflected in their willingess to enter into RDLPs for which the forecast return on investment was 40 percent.

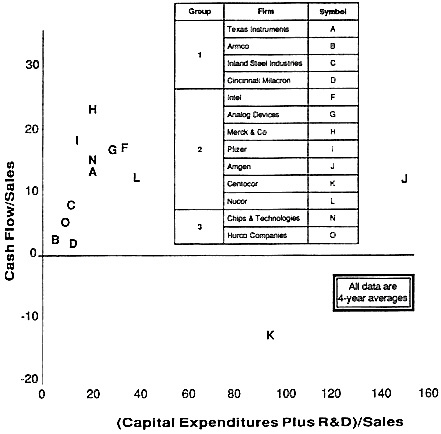

Capital Intensity

Another possible explanation for the differences might be that the firms that emphasize the competitive impact of cost of capital might simply face greater capital requirements. They might be competing in more capital-intensive industry segments or with more capital-intensive strategies than their Group 2 counterparts. We define capital intensity broadly here and include both capital investment and R&D expenditures. In Figure A.2 we have attempted to control for size by dividing capital investment and R&D expenditures by sales. The data again confound our expectations and suggest that capital intensity is not particularly related to executive views on the competitive importance of the cost of capital.

Figure A.2 Cash flow versus capital intensiveness (4-year average, 1986-1989).

-

In semiconductors, both Analog Devices and Intel (Group 2) have been consistently more capital intensive than Texas Instruments (Group 1) over the past decade.

-

In steel, Nucor (Group 2) has been much more capital intensive than either Inland Steel Industries or Armco (Group 1), except during the industry recession in the early 1980s, when levels of spending were roughly comparable. On the other hand, Worthington Industries (Group 2), which is more of a steel processor than a steel maker, is less capital intensive than Inland and Armco.

-

The pharmaceutical companies (Group 2) have been more capital intensive than the machine tool companies (Group 1 and 3).

Financial Health and Capital Availability

It might be argued that the real issue is not capital intensity per se, but the financial capacity to satisfy capital requirements. Here, with the very notable exception of the two biotechnology companies in the sample, a pattern does seem to emerge. As can be seen from Figures A.1 and A.2, the firms in Group 1 tend to have lower profitability and cash flow, and higher debt, than the firms in Group 2. Whether we control for industry or not, the firms that view the cost of capital as an important source of competitive disadvantage are in weaker financial condition than those that do not.

The most straightforward interpretation of this result is that financially healthy firms, whatever their level of capital intensiveness, are better able to finance their investment requirements internally (i.e., out of cash flow), and as a result, are less concerned about the costs associated with raising new funds. This is not to say that there is no cost associated with internally generated funds. Reinvested profit is capital raised from shareholders; there is a cost associated with its use, just as there is a cost associated with the use of externally generated capital. But when firms in a financially weaker condition attempt to raise capital externally—and in the case of such capital-intensive industries as steel and semiconductors, raise relatively large amounts of capital externally—they are likely to be confronted with the need to pay increasing costs for that capital. This may help to explain why they express a greater concern about their relative cost of capital. Interestingly, for several of the Group 1 firms, the problem of cost of capital begins to look like a problem of availability of capital. In theory, capital is always available if one is willing to pay a high enough cost, but in practice, firms like Inland, Armco, and TI may find it impossible to raise by conventional means the capital they believe they need to remain competitive. This appears to be why Inland and Armco, for example, have joined with Japanese firms to build their next generation of plants, and have turned to Japanese sources to raise the capital needed to finance their portion of the joint ventures! In theory, capital is always available for a price, but in practice, in these instances, the capital needed to remain competitive simply would not have otherwise been available.

Market Leadership

Closely related to financial health is market leadership. The Group 2 companies tend to be leaders in their respective markets, whereas the market position of the Group 1 companies tends to be problematic.

-

In Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co. is generally considered to be the most successful firm of the 1980s. Amgen and Centocor are among the

-

handful of survivors of the more than 1,000 start-up companies that originally entered the biotechnology field, and after a decade of product development, they appear poised for rapid and profitable growth. And while Pfizer has had some recent difficulties, it is generally believed to have a well-stocked pipeline of new product possibilities.

-

In Semiconductors, Intel (Group 2) is the world leader in microprocessor technology, and Analog Devices (Group 2) is widely acknowledged as such in analog signal processing devices. In contrast, TI (Group 1) lost its leadership position in memory devices in the mid-1980s, and is now doing everything it can to overcome the formidable obstacles to regaining leadership in an industry dominated by economies of scale and experience.

-

In Steel, the two smaller companies are leaders in their respective market segments. Nucor is generally viewed as the most successful of the ''mini-mill" steel companies that have been competing in the lower-value segments of the steel market (e.g., bar and wire rod products) and that increasingly, are posing a threat to the higher-end segments. Worthington Industries is similarly perceived in the steel-processing (as opposed to steel making) segments that it serves. In contrast, our two Group 1 steel markers, Inland and Armco, while they are among the strongest of the domestic integrated steel makers, face formidable foreign competition.

-

In Machine Tools, our two Group 1 companies lost their market leadership over the course of the past decade, except in the area of plastic injection molding equipment, where Cincinnati Milacron is acknowledged to be the world leader.

While there seems to be an association between leadership and views on the competitive impact of the cost of capital, how exactly is this relationship to be explained? There appear to be a number of plausible lines of argument. The first is almost tautological. The firm that leads does not have to catch up. Catching up, particularly in businesses where learning curves and economies of scale are as important as they are in capital-intensive industries, becomes prohibitively expensive. The firm must come from behind in a field where the leader is always gaining. It must make the investments required to close the gap while at the same time matching the investments and advances that the leaders are making to enhance their position. The problem becomes all the more difficult if, as is usually the case, the firm striving to catch up is in a weaker financial condition than the firm or firms in the lead. The gap between available capital and required capital becomes more severe, which in turn places all the more importance on the costs and difficulties associated with raising the capital required to close that gap. This is exactly the pattern that seems to have afflicted the steel, semiconductor, and machine tool companies in Group 1. Iverson, chairman and CEO of Nucor (Group 2), described this pattern explicitly as he explained his investment philosophy:

In steel, you don't have any choice. You have to keep investing continuously. If you don't, you fall behind. And if you fall behind, it is very difficult and extremely expensive to catch up. This was the problem that the integrated steel makers ran into. You wind up highly leveraged, which gets you into serious trouble during downturns.

Another way to look at this association between leadership and lack of emphasis on the costs of capital as a competitive factor is to consider how the companies in Group 2 have preserved or built their strong market positions. All have done so largely on the basis of technology leadership. Intel and Analog Devices are technology leaders in microprocessors and analog signal-processing devices, respectively; Nucor has long been a pioneer in the steel industry and recently invested $270 million in building the world's first continuous thin-slab cast flat-rolled steel-making facility, while Worthington Industries is the U.S. leader in the application of advanced steel processing technology developed in Europe; Merck & Co. is widely considered the most innovative company in the pharmaceutical industry, Amgen and Centocor are among the handful of successful biotechnology companies, and Pfizer appears to be well positioned technologically.

Moreover, if we were to ask the Group 2 executives to name the most important determinant of their ability to maintain their positions of advantage, their answer would be a continuing capacity to innovate. For the pharmaceutical firms, this means continued leadership in development of major new drugs. For the semiconductor firms, it means continued product leadership in microprocessors for Intel and in analog devices for the company of that name. For Nucor, it means advanced steel-making capacity, in addition to low costs and debt; and for Worthington Industries, customer satisfaction, which requires the most advanced steel-processing facilities in the markets they serve. Whether or not these firms are able to maintain in the future the positions they have built in the past will depend on whether they can continue to outinnovate their competitors. And because innovation, and the ability to continue to innovate, are fundamentally important to the well-being of these companies, the secondary importance given to the cost of capital as a competitive factor becomes understandable. The ability of these firms to maintain their technology leadership will have a vastly greater impact on their long-term profitability than any relative differences in the cost of capital. Conversely, if these firms fail in their quest to preserve technology leadership, the impact on their profitability will far exceed the impact of any relative differences in cost of capital. This is why Laubach, president of Pfizer, emphasized that especially with the advent of the generic drugs, the only way to succeed in the pharmaceutical industry—that is, the only way to continue to generate attractive rates of return over the long haul—is to develop new products, and this requires that the firm be willing and able to invest on average, $230 million of R&D for each new drug, and simulta-

neously to invest in a portfolio of such new drug possibilities. ''If we are going to stay in this industry, we're got to play [the new product development game]. If we don't play, we're out. If we play and lose, we are also out, but it is better to play and try to win, than to walk away."

Our Group 1 companies also explicitly begin with the premise that they are committed to their respective businesses. The difference is that they are working from a position of, at best, technological parity. And when firms in a competitive, capital-intensive arena possess roughly comparable technology, the ability to invest in that technology—that is, the magnitude of available resources—becomes a primary determinant of competitive success. The firms compete not on the basis of their innovativeness, but on their ability to keep up with the industry leaders' pace of investment in state-of-the-art (as opposed to leadership) plant and equipment. Under these circumstances, the cost—and we would argue, availability—of capital becomes a dominant concern. Other things being equal, particularly technology, the firm with access to more or cheaper capital, or both, has the ability to outinvest its competitors. Not only do the firms operating under a less attractive capital environment fall behind, but the gap between them and their competitors can grow very quickly.

CONCLUSION

A growing body of evidence suggests that the differences in the time horizons of U.S. and Japanese firms are deeply rooted in the industrial structure and cultures of the two countries. Whether or not there are persistent, real differences in the cost of capital, Japanese firms will continue to behave for some time to come as if they enjoyed a lower cost of capital. One of the inescapable features of global competition in the 1990s and early twenty-first century will be the presence of foreign competitors with long time horizons—competitors who from a U.S. perspective, behave as if they had lower costs of capital.

The ability to compete against firms that behave as if they had lower costs of capital thus becomes a prerequisite for U.S. firms participating in global markets. How executives in capital-intensive markets view the competitive effects of the U.S. cost of capital, and why some are less concerned about it than others, become especially interesting questions. The simplest and most general conclusion from our survey is that the way to remain competitive against firms that behave as if they had a lower cost of capital is to stay ahead! This seems simplistic, yet the firms in our survey that do not perceive relative cost of capital as a critical competitive factor are those that have succeeded in preserving leadership in their respective markets. Once leadership is lost in a particular market, the firm that is able to behave as if it has a lower cost of capital—whether or not it actually does—has an

obvious advantage. It will be willing to invest at a more rapid clip than its competitors. In other words, to the extent that the industrial and financial structure of Japan enables Japanese firms to behave as if they had a lower cost of capital—the playing field in capital-intensive markets is uneven. Any firms entering that field without some compensating "unfair advantage," without some clear basis for leadership in the marketplace, will inevitably face a losing battle. And once they fall behind, the slope of the field makes catching up all the more difficult.

How have the Group 2 firms in our survey stayed ahead? Apparently by building and then preserving technological leadership. Being state of the art in capital-intensive industries, having technology that is as good as the competition's, does not appear to be good enough, at least on the basis of this limited survey. Technological parity in a capital-intensive business implies that firms are competing on the basis of the rate at which they are willing or able to invest. As long as their structure and culture enable Japanese firms to behave as if they have lower costs of capital, it is difficult to see how any U.S. firm can compete successfully over the long run on these terms. On such an uneven playing field, all that is left as a basis for competition once technology leadership is lost is access to domestic markets, and it is not surprising in these circumstances to see a growth in the number of joint ventures between Japanese firms with capital and U.S. firms with access to domestic markets.

This does not mean that we should neglect efforts to reduce the disparity in time horizons between the United States and Japan. On the contrary, every effort must be made to do so. A broad range of fundamental policy steps will be required. And if the structural and systemic differences that enable Japanese firms to pursue relatively long time horizons are likely to persist, then the important question for the near term becomes; what if anything can firms and the federal government do to offset their effects? This analysis suggests that the answer lies with actions of individual firms and the federal government that enhance or preserve U.S. technology leadership.

NOTES

REFERENCES

Abuaf, N., and K. Carmody. 1990. The Cost of Capital in Japan and the United States: A Tale of Two Markets. Salomon Brothers Financial Strategy Group (July).

DiMasi, J. A., R. W. Hansen, H. G. Grabowski, and L. Lasagna. 1991. The cost of innovation in the pharmaceutical industry. The Journal of Health Economics, Vol. 10 (July) pp. 107-142.

Hatsopoulos, G. N., and S. H. Brooks. 1986. The Gap in the Cost of Capital: Causes, Effects, Remedies. R. Landau and S. W. Jorgenson, eds. Technology and Economic Policy. Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger.

Hatsopoulos, G. N., P. R. Krugman, and L. H. Summers. 1988. U.S. competitiveness: beyond the trade deficit. Science (July 15):241.

Henriques, D. B. 1991. Disguising the risks of research. New York Times, Business Section (February 3): 14.

Kester, W. C. 1991. Japanese Takeovers. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press.

Kester, W. C., and T. A. Luehrman. 1989. Real interest rates and the cost of capital. Japan and the World Economy 1.

Kester, W. C., and T. A. Luehrman. 1990a. Cross Country Differences in the Cost of Capital: A Survey and Evaluation of Recent Empirical Studies. Draft (December 12).

Kester, W. C., and T. A. Luehrman. 1990b. The price of risk in the United States and Japan. Harvard Business School Working Paper, 90-050.

McCauley, R. N., and S. A. Zimmer. 1989. Explaining international differences in the cost of capital. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Quarterly Review (Summer).

Norsworthy, G. N. 1990. Why U.S. manufacturers are at a competitive disadvantage. MAPI Policy Review (November 1990) PR-114. Washington D.C.: Manufacturers' Alliance for Productivity and Innovation.

Zielinski, R., and N. Holloway. 1991. Unequal Equities. Kodansha International. Tokyo.