Courts, Jails, and Drug Treatment in a California County

Mary Dana Phillips

No understanding of the contemporary drug scene in the United States can be achieved without focusing in part on the role of the criminal justice system. Large numbers of drug users and addicts are processed through various phases of the system at one time or another (Peterson, 1974; Weissman and DuPont, 1983; Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1983), and there is an important body of research on the extent of drug use among arrestees, felons, and misdemeanants convicted on drug law violations and drug-related criminal activity, on jail and prison inmates with histories of drug use, and on the criminal records of drug treatment clients (Allison and Hubbard, 1985; Flanagan and Jamieson, 1988; Hubbard et al., 1989). So intertwined are the treatment and justice systems that the goals of drug treatment often directly include the elimination or reduction of criminal activity.

It is difficult to say with precision what proportion of all drug users are involved with the criminal justice system. Although the numbers of individuals arrested and prosecuted for illicit drug involvement are widely used as indicators of the prevalence and severity of the drug problem (Gandossy et al., 1980; Gropper, 1984), these numbers are equally a measure of law enforcement priorities and resources (Sloan, 1980; Krivanek, 1988). The direction of the relationship between drugs and crime—which comes first and which causes the other—continues to be contested (Watters et al., 1985; Inciardi, 1987).

The developing interface between the criminal justice system and community and institutional treatment programs poses a number of practical and philosophical questions. By most accounts, drug use constitutes an ever-increasing problem for the community and for law enforcement,

Mary Dana Phillips is a research associate with the Alcohol Research Group, Institute of Epidemiological and Behavioral Medicine, Medical Research Institute of San Francisco, Berkeley, California.

adjudication, and corrections. This trend has three corollaries in recent history: (1) more offenses are seen to be ''caused'' by drugs; (2) drug and drug-related offenses, as such, are contributing more and more clients to the justice system; and (3) drug treatment is increasingly being sought as an adjunct or alternative to conventional punishment. Whereas public concern over drug-generated offenses has led to a stiffening of sentencing practices and contributed to the crowding of courts and detention facilities, programs that provide treatment and education for addicts and other users are often substituted for regular detention.

This paper offers a preliminary look at the overlap and connections between the criminal justice system and publicly supported drug treatment, assessing at the county level the appropriateness of the relationships between the justice system, drug users, and treatment programs. Although the two systems often work in parallel to handle drug-using persons, choosing from a complex set of alternative responses to particular circumstances, the two systems diverge in orientation and mission: one is designed to render judgment and due punishment according to a moral and legal code, the other to provide diagnostic and therapeutic services for a quasi-medical condition using scientific and clinical principles. The result is tension: political, philosophical, ethical, and instrumental. The recent "drug wars" increase the pressure on both systems to provide winning solutions. There is confusion as to how a person and a problem are to be defined; it is unclear how and when the definition (and thus, solution) changes from a criminal to a therapeutic one. There are different standards applied in different jurisdictions and even within jurisdictions at different administrative levels. Mandates to treatment, like many other judicial mandates, are subject to much local discretion and variability, in terms of selection criteria, sanction patterns, procedures, and the balance between the civil liberties of the individual and the prerogatives of the state (Kittrie, 1971; Wexler, 1973; President's Commission on Mental Health, 1978; Weissman and DuPont, 1982; Brown et al., 1987).

This paper seeks to provide a level of historical perspective to set the stage for a detailed case study analysis. It discusses the statutes that guide the criminal justice/drug treatment interface, the typical practices of the personnel within the systems, and the larger criminal justice and drug treatment ecologies in which they operate. There is reference to the drug treatment literature, the criminological literature on the emergence of alternatives to incarceration, discussions in both literatures on the specifics of the involvement of the two systems, and federal policy-setting documents, such as the papers from the Second National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse (1973a,b,c), the task panel reports to the President's Commission on Mental Health (1978), and the report from the White House Conference for a Drug Free America (1988).

Data for the case study were taken from in-depth interviews with representatives of the criminal justice and drug treatment systems and various state and county statistical and substantive reports. The case study provides a detailed view of a particular region, its statutes and processes, and the gaps that tend to exist between theory and practice. State and local governments have substantial autonomy with regard to how they apprehend and behave toward drug-involved offenders. In-depth exploration of a county jurisdiction reveals both the strengths and weaknesses of its response to drug users. The overwhelming crowding of the courts and detention facilities, the lack of suitable or effective treatment for inmates, and the underuse of community programs—which stems in part from the need for more and different levels of treatment and other supportive services to augment these programs—have policy implications for the county.

THE NEXUS BETWEEN THE DRUG TREATMENT AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEMS

Treatment provision has widened into a "two-worlds" model: one system is for those who have private insurance or can otherwise afford to pay; the other system is funded with public money and designed to treat citizens who cannot pay to receive services. Because publicly funded drug treatment capabilities currently fall short of the demand for services, citizens who cannot pay for their own treatment compete in a stream of referrals from the criminal justice, social welfare, and mental health systems. Only a fraction of those seeking such help can find a timely slot in the publicly funded programs that are squeezed for staff, facilities, and support from the communities they are supposed to serve. Client mixes in drug treatment programs have for years been a combination of people experiencing varying degrees of coercion or motivation to avoid criminal sanctions, but there is an argument to be made for paying closer attention to the composition of the client pool in treatment. Pressure from one's doctor, family, or employer to participate in treatment is symbolically and instrumentally different from a judicial motion to enroll in a program. It is not currently known, however, what effect the proportions of criminal justice-referred and noncriminal justice-referred clients have on treatment experience and outcome (Stitzer and McCaul, 1987; Nurco et al., 1988).

Formal control is the cornerstone of public policy regarding drug-dependent and drug-using persons, and the judicial system has been relied on in a variety of ways to secure and maintain such control. There is a resurgence of interest now in adapting the justice system to assume the task of channeling persons into drug treatment. The issues raised by this

linkage were highlighted in the report presented by the Liaison Task Panel on Psychoactive Drug Use/Misuse to the President's Commission on Mental Health (1978:2118):

Today, the drug treatment system is caught in a fundamental conflict about "what is being treated". The basic confusion commences with the unwillingness of the formal institutional structures to explore the boundaries between psychoactive drug use and misuse. Even that separation is further confused by the question of who decides what the adverse consequences are: the patient, the physician or counselor, or a variety of agencies affiliated with the criminal justice system. The law enforcement establishment circularly labels all use of illegal psychoactive substances as misuse or "abuse," and the medical establishment labels all nonmedical use of psychoactive substances as misuse. Thus, by definition, psychoactive drug use is seen as demanding legal intervention and medical treatment.

The controversy generated by these authors in 1978 remains vigorous (see Anglin [1988] and Leukefeld and Tims [1988] for recent articles covering a range of opinions). Current interest in drug use and drug users is reflected by the regular and frequent discussions of them in the media and by national and local policymakers.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

The connection between the drug treatment system and the criminal justice system is longstanding and complicated. A chronological overview of some of the major legislative, judicial, medical, and social developments of the last century helps to set the scene for a more informed discussion of the present. Several pieces by Weissman detail the history of these developments, and an overview may be found in Drug Abuse, the Law and Treatment Alternatives (Weissman, 1978a; see also Duster, 1970; Musto, 1973a,b; Brecher, 1972; and Inciardi and Chambers, 1974). For a history of opiate addiction in America before 1940, see Courtwright (1982) and Terry and Pellens (1928).

The Criminalization of Drugs

During most of the nineteenth century, all drugs in the United States were licit, including opium, morphine, cocaine, and marijuana, and could be legally sold (Terry and Pellens, 1928; Brecher, 1972); regulation and criminalization occurred in the early decades of the twentieth century (Duster, 1970; Courtwright, 1982). In 1914, largely in response to treaty

obligations derived from ratification of the Hague Convention of 1912, Congress passed the Harrison Narcotic Act (Brecher, 1972; Weissman, 1978a). This act relied on federal customs and excise tax power to require manufacturers, distributors, and dispensers of opiates and coca products to register with the Treasury Department and to keep records of transactions involving these substances (King, 1974). As interpreted in the years after its passage, the Harrison Act in effect criminalized possession, use, and sale of opiates and cocaine for nonmedical purposes; it was the first time in the United States that criminal sanctions were uniformly imposed (Weissman, 1978a). Because doctors were not permitted to administer controlled substances to patients merely to maintain addiction, addicts were cut off entirely from all sources of legal (medical) relief. "Exit the addict-patient; enter the addict-criminal" (King, 1974).

The resultant generational change in the identity of a typical American opiate addict over the last century has been documented repeatedly (Musto, 1973a; Courtwright, 1982). The addicted population of the late nineteenth century was mostly middle-aged, middle-class, small-town white women. It became largely lower class urban males by roughly 1940, often of criminal occupations (Fort, 1968; Courtwright, 1982). Courtwright's view is that the transformation of the American addict was also a function of prevailing medical practices over time: addicts were common in the nineteenth century mainly as a result of physicians' wide use of opiate-based medicines. Patterns of nonmedically induced drug use also began in the nineteenth century but did not account for the bulk of the addicted or drug-using population until after the criminalization of drug use had already begun (Fort, 1968; Duster, 1970). Shifting medical therapies reduced reliance on opium derivatives; the concurrent shifts in American policies toward narcotic addiction, addicts, and users "paralleled and were entirely consistent with the independent and underlying transformation of the addict population" for nonlegal reasons (Courtwright, 1982:4).

Lindesmith, King, Trebach, Brecher, and others have advanced the view that the transformation of the American addict population was a function of abrupt changes in the legal status of the addict. The Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914 forced those who sought narcotics to turn to nonmedical supplies of opiates and increased the likelihood of association with other criminal activities. "The government's anti-maintenance policy succeeded in making a bad situation worse: criminal activity was at least in part a function of [high] black-market prices" (Courtwright, 1982:147). Supreme Court and Treasury Department decisions between 1919 and 1923 established a policy of virtual prohibition that included strict regulation of prescription drugs and criminal sanctions for use of illegal drugs or for illegal use of medicinal drugs (King, 1974; Weissman, 1978a; Courtwright,

1982).

From this time on, drug users and sellers began to constitute a considerable proportion of all those arrested at the federal level (Klein, 1983). Treatment for addicted persons began as a response to the "choking of federal prisons with addict-criminals" (King, 1974). In 1929, in part to relieve the crowding of federal prisons with drug law violators, the Public Health Service and the Bureau of Prisons received congressional authorization to open two narcotic farms: one in Lexington, which was opened in 1935, and one in Fort Worth, which was opened in 1938 (King, 1974; Weissman, 1978a). Addicted persons convicted in federal courts could be sent to these Public Health Service prison hospitals in lieu of ordinary imprisonment (King, 1974). Although the hospitals also accepted voluntary clients, they were run as medium-security penal institutions and had both rehabilitative and addiction research purposes (King, 1974; Weissman, 1978). The criminal justice system and the drug treatment system have "shared" clients, then, ever since punishment became an option for drug addicts in the United States. Some writers have categorized the criminal justice system as the drug treatment system's ''main casefinding mechanism" (President's Commission on Mental Health, 1978; Klein, 1983).

In 1930 Congress replaced the scandal-ridden Narcotic Unit within the Treasury Department's Bureau of Prohibition with the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (King, 1974; Weissman, 1978; Courtwright, 1982). Harry Anslinger was its director until 1962, a period Musto has called "the peak of punitive legislation against drug addiction in the United States" (Musto, 1973a). Mandatory minimum penalties were common for drug offenders; most were not remanded to the farms but to traditional incarcerative settings with other criminals.

Except for heroin, the prescription of narcotics remained legal in the United States. After 1914 some addicts were able to obtain drugs from physicians by exhibiting "symptoms" of an illness. Physicians were under pressure to demonstrate the legitimacy of the patient's condition for whom narcotics were prescribed. At the same time a subculture of users and addicts relied on imported heroin or illegally obtained but legally manufactured pharmaceuticals. Many of the drug users and addicts who were arrested and channeled into the criminal justice system until the 1960s were also found to be heavily involved in other forms of criminal activity.

Reforming Drug Policy in the 1960s

The 1960s were a decade of experimentation, both on the part of drug users and on the part of drug policy administrators. One manifestation of

this prevailing mood was the report, Drug Addiction: Crime or Disease? issued in 1961 by the Joint Committee of the American Bar Association and the American Medical Association on Narcotic Drugs. Heavily indebted to the work of Indiana University sociologist Alfred Lindesmith (1965), it called for an open and, when necessary, critical discussion of the current policies and laws governing the handling of narcotic substances and those who used them. Without attempting to provide solutions, it reflected "a degree of dissatisfaction within the legal and medical professions concerning current policies which tend to emphasize repression and prohibition to the exclusion of other possible methods of dealing with addicts and drug traffic" (Joint Committee of the American Bar Association and the American Medical Association on Narcotic Drugs, 1961:161). Some of the report's conclusions were that medicine and public health could be called on to make greater contributions to the handling of drug-involved offenders, the prevention of problems needed a place in the debate, and outpatient or community-based care ought to be explored. Overall, more research was needed, especially to explore an expansion of treatment services and to establish a basis for more balanced and informed debate.

The White House Conference on Narcotics and Drug Abuse was convened in 1962, and rehabilitation rather than punishment emerged as its theme (Weissman, 1978a). Lindesmith's classic contribution to the debate, The Addict and the Law, appeared in 1965. It highlighted the subtle and complex nature of the issues that frame whether drug users are treated as criminals or as individuals with a disease. In addition, it provided further intellectual inspiration to the energies then moving toward reform.

In 1961 California authorized the involuntary civil commitment of narcotics addicts in need of treatment. The use of coercion to induce treatment became sanctioned by the judicial system; accordingly, the treatment that was delivered retained a more punitive than therapeutic tint. In California the Civil Addict Program was administered by the Department of Corrections and not by a health or drug and alcohol department.

Early California rehabilitation legislation had two main emphases: (1) short-term crisis intervention and detoxification programs in the community for gravely disabled drug-dependent persons, and (2) long-term post-conviction inpatient treatment and closely supervised parole (under the Department of Corrections) for addicts only. Legislation in 1972 encouraged multimodality community-based outpatient and inpatient programs, including methadone maintenance. This legislation (partly reflected in current California statutes—see Appendix A) also provided for diversion into treatment of drug law violators from the criminal justice system; it has since been expanded to allow diversion of people with other types of offenses as well (Second National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, 1973a).

New York passed a similar law in 1962. Similar federal legislation, the Narcotic Addict Rehabilitation Act (NARA) of 1966, also set the stage for massive federal funding of treatment programs in the 1970s. This legislation provided more broadly for civil commitment as an alternative to prison. NARA authorized (1) pretrial civil commitment in lieu of prosecution for persons charged with certain nonviolent, nontrafficking federal crimes who could convince a federal district attorney that they were addicted but had a high probability of rehabilitation; (2) voluntary civil commitment for addicts not under criminal charges, a program administered by the National Institute of Mental Health; and (3) sentencing of some addicts convicted of certain federal crimes to commitment for treatment, a program administered by the Bureau of Prisons. The clients of the latter were treated in selected prisons and could then be paroled to outpatient care in the community. NARA also authorized federal grants to communities to fund treatment programs for addicts (Bonnie and Sonnereich, 1973; King, 1974; Maddux, 1988).

According to the report and appendices of the Second National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse (1973a,b,c), civil commitment is not a treatment mechanism as such but rather a mechanism for retaining and supervising individuals while they participate in a course of treatment. It is in this enforced and prolonged supervision that it differs chiefly from voluntary programs. Maddux (1988) has recently reviewed 50 years of clinical experience with addicts in treatment, including those being treated voluntarily, those under various criminal law coercions, and those under civil commitment, using data from the U.S. Public Health Service hospitals and from NARA. He concludes that civil commitment brings people into treatment who might not otherwise get there. But it cannot assure their participation, it cannot overcome deficits in services, and it remains restricted by constitutional guarantees of individual liberty (Maddux, 1988).

The shift to view addiction as a health issue rather than (only) a criminal or moral issue was well under way by the mid-1960s. The idea that intractable social problems—such as drug problems—undergo periodic redefinition and are turned over to or are shared by different social institutions and occupations has been developed extensively in the literature (Gusfield, 1967; Pitts, 1968; Brüün, 1971; Room, 1978). This change in perspective led to what has been called "the medicalization of deviance" (Gusfield, 1967; Pitts, 1968; President's Commission on Mental Health, 1978; Conrad and Schneider, 1980): the identified "deviant" is committed to a hospital instead of a prison, and the objective becomes curing rather than punishing (Wexler, 1973; Glaser, 1974; see Kittrie, 1971, for a detailed legal and philosophical history of these shifts).

This reaction to some but not all types of drug addicts and users accelerated rapidly after 1962, when Robinson v. California was decided by

the Supreme Court. The case involved an appeal from a misdemeanor conviction under a statute that made it unlawful to be "addicted to narcotics." The Supreme Court held that to penalize an addict was a violation of the Eighth Amendment provision against cruel and unusual punishment: the conviction was not based on anything the defendant had done but on his illness (Sloan, 1980); the statute was thus ruled unconstitutional. The ruling also suggested that it would be legitimate to declare addiction a disease justifying civil commitment (Glaser, 1974).

During the 1960s the amounts and types of drug use, and the ways people were using drugs, as well as the social class of users, changed as well. Drug users were no longer exclusively associated with patterns of frequent street crime. Experimentation with a variety of substances, including marijuana, LSD, amphetamines, and prescription pharmaceuticals, became widespread. People from middle and upper class backgrounds joined the ranks of those who used a variety of licit and illicit substances for pleasure, or "kicks," as well as for generational symbolism, including displaying disapproval of the mores of society and the policies of government.

The criminal justice system itself was in the throes of upheaval and experiencing a period of disenchantment with traditional practices and their underlying philosophies. This was a time of riots in the prisons and exposés in the media of cruel and unusual conditions within them (Packer, 1968; Goldfarb, 1975; Feeley, 1983). High rates of criminal recidivism among drug users and a continuing rise in the cost, frequency, and seriousness of crime linked to drug users frustrated officials and perhaps encouraged them to try something else (Ohlin, 1973; Weissman, 1978). A philosophy that proposed humane rehabilitation and opportunities for treatment in place of deprivation and incarceration for those whose criminality could be linked to drug use found resonance in a criminal justice system looking for alternatives to traditional but unsuccessful methods (Jaffe, 1979).

Treatment approaches for drug users, especially heroin addicts, expanded as a part of a "war on heroin" and, more generally, reactions against drugs, crime, and accompanying lifestyles (Second National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, 1973a; Klein, 1983). Law and order campaigns in the late 1960s and early 1970s drew support from the fears of a voting populace that had been assailed by anti-Vietnam war activities, the civil rights movement, student unrest, and more broadly defined cultural shifts among youth with respect to both drug use and sexual behavior.

Treatment provided opportunities for recovery and encorporated more progressive methods of dealing with drug users than imprisoning them. Nonetheless, treatment was also seen as a way of maintaining careful

supervision of drug-involved offenders, only partially extricating them from the traditional criminal justice system. The Nixon administration's "War on Drugs" had weapons to reduce the supply side, including the Drug Enforcement Agency to interdict imported substances, and "get-tough" laws to reduce the ''demand" side through the detection and punishment of users and the deterrence of future consumers.

At the same time there was substantial growth in the federally and state-funded social service apparatus. Demarcations between treatment as a part of the social welfare and health care systems and the criminal justice system were becoming less clear. "Community-based" programs were favored over incarcerative models for juvenile delinquency prevention, health (especially mental health) care, and other public services (Fox, 1973; Wexler, 1978). Both political and fiscal considerations were at work here; decarceration was envisioned as more efficient, serving more people per dollar. The local service providers welcomed a chance to provide flexible care at the local level where they had greater authority and discretion. This marriage between community care providers and judicial system referral mechanisms resulted in a vast network of treatment opportunities for people whose original interaction was with the justice system. The marriage was paid for by federal-state cost sharing during the early 1970s.

Diversion from the Criminal Justice System to Treatment in the 1970s

The demand for policy alternatives offering the penal features of criminal law but the therapeutic features of health care had been building for half a century. The growth of the federally funded system of community-based programs authorized by NARA and later by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) made the practice of court referral of addicts to community treatment a commonplace. In 1972, through the efforts of the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention (located in the Executive Office of then-President Richard Nixon), the routing of addicts to treatment was further increased by the referral of unsentenced defendants to community-based treatment in lieu of prosecution. This move was based on the assumed causal relationship between drug taking and criminal behavior. It was buttressed by a coexisting belief that treatment was beneficial for drug-dependent persons, whether such treatment occurred voluntarily or involuntarily (Smith, 1974). This system interface—and the assumptions underlying it—remains at the heart of the national approach to drug users.

Diversion at the pretrial stage of the adjudication process was made possible in the United States by recommendations of the President's

Commission on Law Enforcement. The commission proposed the practice in 1967, claiming that "it is more fruitful to discuss, not who can be tried and convicted as a matter of law, but how the offices of the administration of criminal justice should deal with people who present special needs and problems.. .[the solution being] the early identification and diversion to other community resources of those offenders in need of treatment, for whom full criminal disposition does not appear required" (President's Commission of Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, 1967:134). Diversion was originally designed for alcohol-involved offenders and people with chronic mental problems, but it quickly became popular for a variety of dispositions. These offenders were seen to be burdensome to the criminal justice system, preventing it from catching and punishing "real" criminals more efficiently. Moreover, in the words of two veterans of the American judicial system, it offered "the promise of the best of both worlds: cost savings, along with rehabilitation and more humane treatment" (Vorenberg and Vorenberg, 1973; see also the Yale Law Journal, [1974]).

The classical definition of diversion is therapeutic intervention that takes place following arrest but before either a trial or adjudication. Several of the papers found in the appendices to the report of the Second National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse (1973b,c) include the following procedures as falling under the category of diversion:

-

pre-arrest, formally authorized diversion for purposes of detoxification or withdrawal;

-

postarrest, diversion to detox;

-

treatment as a condition of pretrial release;

-

emergency treatment while awaiting trial;

-

treatment in lieu of prosecution;

-

treatment as a condition of deferred entry of a judgment of guilt and conditional discharge, or as a condition of suspension of sentence or probation;

-

treatment as a condition of probation or parole; and

-

commitment for treatment in lieu of other sentence, or while serving a sentence in a correctional facility or following administrative transfer from a penal institution.

Nationwide, procedures at the local court level that may be formally designated or loosely categorized as "diversionary" are many and varied. Diversion programs vary not only with respect to a lack of uniformity of procedures but also in the extent to which the defendant penetrates the criminal justice system, a factor that may vary even within states by county or judicial jurisdictions (Carter, 1972; Agopian, 1977; Weissman, 1978b;

1979; Gottlieb, 1985). Specific operations may be driven in part by legal or policy considerations, fiscal realities, the relative climate of the local courts, and the size and schedules of their caseloads. Some diversionary procedures derive their authority from statute law, whereas others rely on court rules or prosecutorial discretion. However indirectly, all rely on the existence of (and availability of space within) treatment programs. Most diversion programs seem to share certain goals and principles. These include the early identification and referral to treatment of drug-involved offenders, goals that allow the workload imposed on the criminal justice system to be reduced by the volume of drug-related cases that are dispensed with in an alternative fashion.

At its best, diversion allows the court to recognize the seriousness of official concern for certain offenses while retaining a flexible range of alternative sentencing measures at the pretrial stage of the proceedings. It was designed to benefit the defendant, prosecutors, the court, and the community. As an alternative to standard options, diversion is also appealing because it represents a continuing attempt to structure and make visible many informal prosecutorial practices found across a range of dispositions. It may also be submitted as evidence of an ideological shift in emphasis from deterrence to rehabilitation; pretrial diversion minimizes penetration into the formal processes of the justice system. As a result, diversion is endorsed as a process capable of avoiding the stigmatizing experiences of traditional justice system processing.

Diversion, not unlike probation, may be seen as both an exchange and as a sentencing process. As in plea bargaining, there is a ''legitimate exchange of tactical concessions to the mutual advantage of the defense and the prosecution" (Yale Law Journal, 1974:843). Diverted cases and defendants allow costs associated with traditional adjudicatory and correctional practices to be averted. Society in turn is expected to benefit from reduced recidivism rates linked to diversionary practices that are characterized as therapeutic rather than punitive.

At its worst, diversion may be viewed as a supralegal mechanism, a tool available to the court to dispose of defendants and cases using alternative strategies that do not uniformly adhere to laws and procedures specifically in place to protect defendants' civil liberties (Second National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse, 1973a,b,c, Senay et al., 1974; Yale Law Journal, 1974; Alper and Nichols, 1981; Harrington, 1985). Critics of diversion share common concerns about the guarantee of due process rights during diversion procedures, which stem in part from the enormous variance in the extent to which defendants penetrate the system. A failure in the adjudication process to define clear boundaries that are explicitly linked to judicial practices and based in the law often allows unpredictable and even disturbing levels of discretion to be exercised by

the courts. Violations of due process are best prevented through the systematic use of procedural safeguards that are explicitly required and based in constitutional law and that are comprehensive with regard to the shifting patterns of diversionary cases and clients (Klapmuts, 1974; Harrington, 1985). Otherwise, efforts to evaluate diversion programs are placed in a precarious position along with more basic constitutional guarantees. Although diversion programs are not necessarily invalidated by these concerns, procedural safeguards of due process rights are not always fully observed.

Research on police behavior and lower courts in the early 1960s suggested that official attitudes and practices toward defendants were best characterized by a crime control model rather than a due process model (Packer, 1968; Harrington, 1985). The court reforms of the late 1960s to the mid-1970s were concentrated on the lower courts and on delineating the amount of discretion police, prosecutors, and judges had in previously unregulated proceedings. The ideal of diversion is an "attempt to structure and make visible the informal prosecutorial practices on noncriminal disposition" (Yale Law Journal, 1974:852). This involved the use of procedural fairness and official guidelines to control official discretion, not increase it, and to protect rather than jeopardize individual rights in these situations (Harrington, 1985). Thus, diversion was not just "a unique approach to the management of deviance but an essential part of a much broader movement of social and criminal justice reform" (Klapmuts, 1974).

The rapid and sweeping moves of federal and state governments to establish and support diversion programs represent a convergence of several complementary forces. Discussions were held in 1971 by the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, the White House's Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention, and the National Institute of Mental Health's Division of Narcotic Addiction and Drug Abuse (NIDA's predecessor) on how to link treatment and the judicial process, thereby interrupting the relationship between drugs and property crimes (Bureau of Justice Assistance, 1988). The resulting federal initiative, modeled after earlier experiments with diversion projects in New York City and Washington, D.C., was funded under the Drug Abuse Office and Treatment Act of 1972 and was known as Treatment Alternatives to Street Crime (TASC). The program represented a formalization of various criminal justice pressures to move addicts into treatment and hold them there for as long as was indicated.

TASC components include identification of the drug-dependent offender, assessment of the individual's drug dependency and community risk, referral to the appropriate community treatment resources, and case management of the individual to maintain compliance with justice and treatment criteria (Toborg et al., 1976). When arrested, the suspect is

evaluated by a diagnostic unit and held pending transfer to a treatment program. Dropping out of treatment prematurely or any other act of noncompliance is treated by the courts as violation of the conditions of release. TASC program participants are under direct supervision of the court, the treatment program, and the TASC worker assigned to their case. Because of the leniency of some treatments, TASC programs often diverted those who were not addicted to an illicit substance and for whom criminal conviction was seen as too severe, such as occasional users of marijuana.

TASC originally focused on pretrial intervention, but this approach was resisted by some courts and prosecutors and was broadened or constrained according to local preferences (Weissman, 1979). By 1974, each locality was allowed to decide whether screening was to be mandatory or voluntary and to determine eligibility standards, points of referral, choice of treatment modality, and criteria of success (Kadish, 1983). Advocates of the program extol its evolution from originally a heroin addict identification program aimed at crime reduction into a social services and treatment brokerage system for criminal justice adjudicatory and offender-serving agencies (Weissman, 1979).

TASC was funded through the 1970s by both federal and state dollars to the local community, usually either a county or greater municipal area. In an article reviewing every state's drug diversion policies in 1979, Weissman demonstrates the broad discretion states exercised in how programs were administered. The federal government last provided money and specific procedural guidelines by direct allotment to states or local communities in 1980. Since then, diversity in state and local practices has only increased, as both program rules and funds are no longer directly overseen by a federal body that provides some measure of uniformity. TASC money became part of what is still available under the federal block grant program, but there is enormous variation in programs and program components currently in operation and funded by TASC block grants. A broad range of legal, fiscal, and philosophical judicial systems design and administer programs that compete for support. TASC may be seen as successful in the sense that many jurisdictions have continued to offer programs that were begun with pre-block grant federal funds and have received support for them from both state and local government sources (Weissman, 1978b, 1979). Currently, 100 sites in 18 states have programs using the name TASC (Bureau of Justice Assistance, 1988).

There has been no systematic comparison of all these programs with one another, especially to review and evaluate their components and the relative success or failure of services for the drug-involved offender in treatment. The evaluations of some TASC programs point to its ability to keep people in treatment longer, but they do not necessarily show

better results once treatment has ended (Bureau of Justice Assistance, 1988). "These studies have also shown that the lack of data collection and evaluation as critical program elements has hindered TASC programming" (Bureau of Justice Assistance, 1988:6).

The TASC philosophy and program components lend themselves to compartmentalization; various combinations of services and functions are adopted by jurisdictions with specific funding or legal restrictions. One part of the TASC program that may be active in one place, such as TASC workers acting as advocates for their clients with the criminal justice system, may not necessarily be found in another (Weissman, 1979). This in fact has been one of the criticisms of the strategy: that it is different everywhere; diversion as part of the judicial system is under state jurisdiction, and many states in turn give local courts the power to interpret state laws using their own discretion.

Programs described as "diversionary" or "community-based" are potentially more effective in achieving the desired result of rehabilitation. There is no question that a medically managed detoxification is preferable to ''sweating it out" in a cell. There is also little doubt that the criminal justice system can introduce people to treatment who might not otherwise ever experience it. Yet the potential for abuse latent within the administrative discretion operationalized in many diversion programs is also real (Yale Law Journal, 1974; NIDA, 1978; Toborg, 1981; Mosher, 1983). Hudson and colleagues (1975:19) issue a sharp warning that may yet deserve attention:

[The potential for abuse] is especially the case when clearly articulated and openly established program policies and procedures are lacking. Most diversion programs are viewed as treatment or quasi-treatment alternatives to conventional processing by the criminal justice system. These programs, however, have in common with the criminal justice system a governmental policy aimed at solving social problems by obtaining individual compliance to a given social structure. Given the assumption that most of these programs provide closer surveillance or supervision of their clients, have quicker reactions to client behaviors, and greater political leverage with community decision-makers, what may begin as a benevolent program designed to help the offender could turn into a more oppressive program than the conventional correctional alternative.

The debate about the relative value of mandates to treat drug-involved offenders continues. For more current discussions of diversion, probation and the nexus between the criminal justice and drug treatment systems, see Chambers and coworkers (1987), NIDA Monograph No. 86 (Leukefeld and Tims, 1988), Brown and associates (1987), and the entire issue of the Journal of Drug Issues (Anglin, 1988) on the compulsory treatment of opiate dependence. At this juncture, however, it is instructive

to turn to the case study of a California county as a critical departure for more general remarks about the pathways to treatment from the criminal justice system.

CASE STUDY OF A CALIFORNIA COUNTY

The California county analyzed here1 is a case in which no formal TASC-type program exists to guide the courts and treatment providers as they interpret the laws regarding drug users as the basis for intervention. No formal program has ever existed within this county's criminal justice system to systematically broker for treatment services. This function has always been a part of the domain of the probation department. In contrast to numerous other California counties and administrative regions around the country that have TASC programs or other formal mechanisms that are specifically assigned to the management of criminal justice-referred drug treatment clients, the county's drug treatment system has no personnel, programs, or program components specifically designed to manage criminally involved clients.

The case study site was a choice of convenience. The experiences and practices of a single county are probably neither unique nor typical but representative in a generic way of non-TASC jurisdictions, which constitute the great majority of counties across the country. The purpose of this inquiry is to examine objectively how the criminal justice and drug treatment systems are linked, how the links have withstood or resolved some of the previously identified tensions, and how the "system" continues to function in the absence of a formal arrangement.

Data in this section were drawn from a series of in-depth interviews with administrative officials connected to both systems, as well as with both clients and treatment providers in methadone programs, residential treatment settings, outpatient programs, and two of the county's detention facilities. Other sources include the California State Penal Code and statistical reports compiled by the Judicial Council of California, the California State Department of Justice, the county municipal court system, the probation department, the county's detention facilities, and the Drug Abuse Program administrative office.

Before examining the relationship between the criminal justice and drug treatment systems, it is helpful to have an overview of the study county. It includes urban, suburban, and rural areas. A full range of socioeconomic statuses can be found in its mix of older industrial towns and neighborhoods as well as in its newer technocratic urban centers and their accompanying housing and commercial developments. Like all California counties, its criminal justice system is governed by the state

constitution and laws.

The population of the county was approximately 750,000 in 1987, with nearly 80 percent residing in cities and the remaining 20 percent in unincorporated areas. The majority of the county's residents are white (85 percent), with blacks representing somewhat less than 10 percent of the total. People identifying themselves as being of Spanish origin make up most of the remainder.

The county is characterized by communities in which individuals, no matter what their ethnicity, tend to share socioeconomic status. The mean income of all families was $30,000 in 1979, but when the population is stratified by race and the mean family income is recalculated, white and Asian families enjoy incomes above the county mean. Black and Native American families and families of Spanish origin have family incomes considerably below the county mean, although only 8 percent of the total county population live below the poverty level. One geographically segregated section of the county also contains a large proportion of minority and poor individuals. One could say that the county is basically a wealthy suburban area with pockets of poverty.

County Drug Abuse Treatment System

The county Drug Abuse Program is a branch of the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Division, one of five divisions within the county's Department of Health Services. The drug program administrator reports to the deputy division director and is advised by a drug abuse advisory board. The county-operated drug programs each employ a program director who reports to the drug program administrator. The program directors are responsible for facility management, staff supervision, and the provision of direct services.

Some programs are run by the county, and others provide services on a contract basis. The budget for all programs was nearly $2 million for FY 1986-1987. Funding sources for program activities can be broken down as follows: 45 percent state, 23 percent federal, 16 percent Medi-Cal (a California state program roughly similar to Medicare), 3 percent user fees, and 13 percent county funds. The types of services offered in the county are prevention, education, and treatment for youth; prenatal and perinatal educational services for women; and outpatient prevention, education, and some treatment services for parents, families, and some individuals. The Drug Abuse Program Office uses its funds to provide residential treatment (23 percent), methadone treatment (17 percent), and prevention and outpatient counseling services (50 percent); the remaining 10 percent is spent on administration and overhead. The number of county employees

working in drug services as of September 1988 was 16. The number of county contractor program employees working in drug services as of September 1988 was 39.

The county provides a range of services in its 11 outpatient counseling and education programs. These include primary prevention and secondary prevention or early intervention with those identified as being at high risk for drug abuse. Targeted clients of these programs tend to be adolescents, other school-aged children and adults who are part of the targeted adolescent's family, and pregnant drug-abusing females. The number of outpatient treatment program admissions for FY 1987-1988 was 693. (This figure does not include those who participated in education and prevention programs.) Of those admissions, 22 percent were black, 68 percent white, and 9 percent Hispanic; 42 percent of the total were women.

The county operates two drug-free adult residential treatment programs, one coed and one for males. Both offer care from 12 to 16 months; the all-male program is licensed for 30 adults, the coed facility, for 15. The number of residential treatment program admissions for FY 1987-1988 was 167. Of those, 56 percent were black, 39 percent white, and 5 percent Hispanic; 36 percent of the total admissions were women.

Methadone services for both detoxification and maintenance are offered at two sites in the county. Within the last two years the county has introduced a fee-for-service type of payment scheme, quadrupling the number of available slots while cutting the number of publicly supported patients. Of the 150 detox slots, 14 are publicly supported; of the 300 maintenance slots, 140 are paid for by Medi-Cal. The county's methadone budget was cut in half in 1988; it accounts for only 17 percent of all drug treatment monies in the 1988 budget, down from the 35 percent share it had in 1987. For the paying clients, methadone maintenance costs $165 per month; detox costs $250 for a 21-day dosing schedule.

The source for the above information is a report commissioned by the Health Services Department and the county's drug abuse advisory board; it includes a multiyear plan for drug abuse services. Some of the report is a series of tally sheets required by the state for funder accountability, much of the rest of it deals with the advisory board's elaborate planning process to meet its goal of a drug-free county. Although some mention was made of monitoring activities to evaluate the progress made toward measurable objectives, neither the report nor the administrator had any data that provided evaluative outcome information. One of the objectives of the report was to evaluate existing services as a part of the planning process. The priorities of the board are reflected in the levels of funding.

The report is inconsistent in several respects. In the first place, one

of the indicators cited as proof of the severity of the drug problem is the large number of county residents identified as being at high risk for drug abuse. This group includes people living below the poverty line, especially minorities, disproportionately high numbers of single and divorced persons under age 30, and people who are too old or too young to be in the work force. Yet very few of the planned or extant services are directed toward these populations. Furthermore, much of the statistical information in the report detailing the county's drug problem was taken from criminal justice system data (reviewed in the next section) and other data estimating the number of current illicit drug users. Very little mention is made in the report of plans to meet the treatment needs of these people.

The problem indicator data do not appear actually to govern the setting of priorities for types and levels of services offered by the county. The bulk of the county's drug budget goes for prevention or education activities aimed at youth and their families who are not identified as necessarily being single or divorced, minority, elderly, between the ages of 15 and 29, or criminally involved. Instead, services are designed for grade school-aged children and their parents. Programs are sited pre-dominantly in middle-and upper-class neighborhoods where contributions from the schools augment county efforts. Another goal emphasized in the report was to secure increased funding or to broaden current service delivery through other means, including third-party payments to county-sponsored services, the use of self-help groups as a part of treatment and aftercare, and increasing both public and private funds to service providers.

There is little mention made of criminal justice system referrals to county-funded programs. One out of eight methadone and residential treatment clients' referral sources were reported to be from the criminal justice system. Most program clients were self-referred, even to these modes of treatment for which nationwide the percentage of criminal justice system-referred clients is closer to 50 percent (Hubbard et al., 1989). Commenting on this fact, "[t]he Planning Committee [of the case study county] noted that only a small percentage of the total arrests for drug-related violations were referred for treatment. This is unfortunate as the cost of treatment is lower than the cost of incarceration; and treatment is more likely to assist the person in adopting a productive, crime-free lifestyle." One of the 12 recommendations in the report was to establish 50 long-term and 50 short-term beds for incarcerated individuals in need of residential treatment, but publicly funded special services neither exist nor were planned for nonincarcerated criminally involved illicit drug users.

There were few data available from the drug abuse treatment system report or from interviews conducted with providers to identify or elaborate the linkages between the drug treatment system and the criminal justice system. For example, the drug abuse program administrator stated his

commitment to cooperate with the probation department, but there was no evidence that justice system-referred clients deserved special consideration. The administrator stated that they were evaluated as candidates for treatment along with everyone else; in his mind they were perhaps disadvantaged to the extent that they were often without funds to help pay for their care and were additionally burdened with their criminal records. His feeling was not that drug users identified by the criminal justice system did not need treatment but that he ''had his hands full" securing the money to provide the rest of the community with services. No mention was made of potential linkages with the justice system or joint funding schemes to begin to serve criminally involved illicit drug users, despite the stress their presence placed on the county's drug treatment and criminal justice systems.

A worker in one of the methadone clinics mentioned the difficulty of working with criminal justice personnel because of a lack of understanding on their part about methadone treatment. For example, her clinic writes letters verifying the dosing schedule of a client rearrested during treatment, despite the reluctance she senses on the part of the justice system to provide methadone to incarcerated offenders. (According to her, criminal justice personnel view methadone more as a drug and less as a medicine.) She also expressed the need for some of the judges and probation officers to appreciate the different types of treatment that were available as well as what could realistically be expected in terms of progress and outcome for the client-offender. She spoke of trying to explain to criminal justice system personnel, for example, why a drug-free residential setting was not an appropriate referral for a methadone maintenance client. She said that there had been a movement under way in the county for the last several years in favor of drug-free treatment.

The cut in methadone funding is clearly a reflection of the county planning committee's sense of priorities. The report stated that, although heroin addicts make up a relatively small proportion of the total drug abusers in the county, their treatment had historically consumed a substantial percentage of available county resources. To this trend may be added the increasing popularity of fee-for-service payment schemes in the county, especially for expensive services like methadone. Thus, cuts in the drug budget for publicly supported methadone slots were almost unanimously supported. This sentiment exists in contrast to another priority of the county, which is to provide services to clients with a high risk for HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection. Education has been identified as the means to this goal, in place of continuing the previous level of publicly supported methadone slots.

Both people who are diverted from the criminal justice system and those who are given probation as a condition of their release rely pre-

dominantly on publicly funded, community-based treatment programs. These are each discussed in turn below. The contradictions implied by the overlap of punitive with therapeutic measures as a response to drug-using offenders in this county are mentioned. They may reflect more general societal confusion regarding the handling of illicit drug users who are apprehended by the criminal justice system.

The Criminal Justice System: Processing the Offender

This section contains a description of the county's criminal justice system, its law enforcement agencies, court system, and detention facilities. It attempts to trace the progression of an offender through the system from the point of initial detention to the time of sentencing. Because the county has sole jurisdiction over offenders accused and prosecuted in its municipal courts, only those offenders who are processed in this system are discussed. The California state constitution provides the mandate for all its counties to have identical processes for such activities. Many dispositions are available for individuals whose cases are drug related. Here, the focus is on the most common pathways to drug treatment through the criminal justice system rather than the identification of every possible trail or outcome.

The county's criminal justice system is the joint enterprise of a number of interrelated institutions: (1) the police, who apprehend the offender; (2) the judiciary or court, which insures due process; (3) the jail, which detains or incarcerates the individual; (4) the public defender's office or private lawyers (or both), whose task is to defend the accused; (5) the district attorney's office, which prosecutes the accused; and (6) the judge, who determines whether prosecution is proceeding lawfully and then sentences the convicted. Of the county's total criminal justice expenditures for 1986, 54 percent went to law enforcement, 7 percent to prosecution, 3 percent to public defense, 12 percent to courts and court-related matters, and 24 percent to corrections.

The police provide protection for the citizenry, bring charges against putative offenders, and have the power of arrest. The county's chief police officer is the sheriff. The sheriff's office has police jurisdiction over all unincorporated areas of the county and 4 recently incorporated towns that contract for police services from the sheriffs office. There are 11 incorporated areas in the county with independent city police departments. In addition, a variety of special districts or local institutions have autonomous police forces: for example, the California State Police, the California Highway Patrol, community college patrols, regional district park

rangers, and railroad and other transportation authority police.

All such police have arrest power, arrest being the act of taking a putative offender into custody—that is, temporarily depriving him or her of liberty. An arrest may occur because a police officer (or a citizen) has observed an offense or has reason to suspect that someone has committed an offense, or because a warrant for arrest has been issued by the judiciary to the appropriate police department. A citizen may also be taken into temporary custody without an arrest having occurred—for example, when a person is sought for questioning about some offense and released, or when he or she is taken to the police station but the peace officer determines that there are insufficient grounds for making a criminal complaint and releases the individual.

A little more than 3 percent of all adults in the county were arrested for misdemeanor offenses in 1986, a proportion that stayed roughly equivalent in 1987 and 1988. Of the total number of adult misdemeanor arrest offenses reported by law enforcement agencies in the county in 1986, 7.9 percent were released at the police level, and misdemeanor complaints were sought in 92.1 percent of the cases. More than 16 percent of the people arrested for a misdemeanor offense were women.

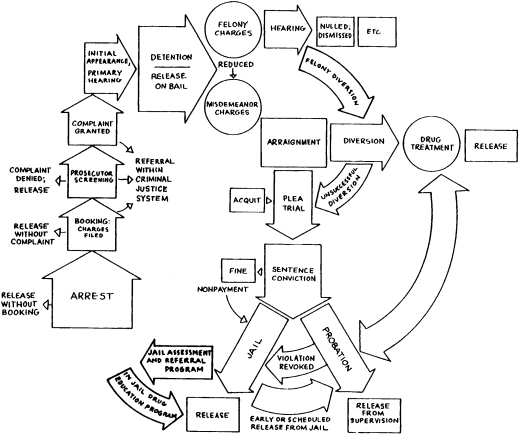

The various stages of the criminal justice system through which a person must pass appear in Figure 1. The first opportunity for diversion from the system occurs during the prearrest phase. The arresting officer determines that the person in custody is in need of detoxification from drugs or alcohol, or both; California law allows for that person to be taken to a legitimate facility for detox services. However, a police officer may still lodge a complaint against a person who is suffering from an illicit drug overdose or drug-related medical problem even if they are delivered to a hospital or clinic because drug use itself constitutes a violation of the drug laws and is thus regarded as a crime. (The same is not true for alcohol intoxication because alcohol is legal.) There are scores of specific laws concerned with the use of illicit drugs and the misuse of licit drugs in the various California codes, including the Penal Code, the Health and Safety Code, the Motor Vehicle Code, and the Business and Professions Code.

Whether or not an arrest has occurred, technically speaking, a putative offender who has been deprived of liberty is detained either in a city lock-up (in one of the 11 incorporated municipalities with independent police departments) or at the main county holding facility. Currently, many misdemeanants are charged and released without being taken into custody, a procedure known as a "cite release." After being taken into custody, the citizen may be (1) booked, issued a "Notice to Appear," and then released, (2) booked, held in custody until a bail amount is set at a hearing, and then released when bail is paid, or (3) booked and held in

custody until arraignment. The admission of the citizen into the jail-whether he or she is held or later released—is called the "booking."

The next step in processing is arraignment, a judicial proceeding in which the accused citizen is formally charged with an offense in public court by the district attorney's office. It is the initial court appearance of a person charged with a crime. When the charges involve misdemeanor offenses the case remains in the lower, or municipal, court.

Felonies refer to all offenses punishable by imprisonment in a state prison or by death, including certain crimes charged under the Vehicle Code. Such complaints are filed in municipal courts for a preliminary hearing to determine if there is sufficient evidence to adjudicate the offense in a superior court. Even when the case is consigned to a higher court, it may be reintroduced at the lower court level if the felony charges are reduced to misdemeanor charges (indicated by arrows on Figure 1).

The county is divided into four judicial districts or municipal court jurisdictions in which all arraignments occur. The State Code requires the district attorney to evaluate information provided by the arresting officer and to decide whether to prosecute or bring to trial the person charged with or reasonably suspected of the offense. Thus, not everyone who is detained is technically arrested and booked, but everyone who is booked is arraigned. At the time of arraignment the district attorney may dismiss the charges against the defendant because of improper arrest procedures or insufficient evidence to prosecute, or if so instructed by the court.

At arraignment the defendant is given a chance to plead and to designate a private defense attorney or request that a public defender be appointed by the court. One may (1) "plead out," or plead guilty immediately, (2) defer the plea until counsel has been procured by "standing mute," which is the same as pleading not guilty; or (3) plead not guilty. In addition to dismissal, other misdemeanor cases are disposed of during arraignment through bail forfeiture, actions after pleas of guilty, or by transfer to another court. After arraignment, the court sets a date for another hearing, either to hear evidence by the prosecuting and/or defending attorneys or for sentencing, depending on the plea.

It is at this point that presentencing diversion is possible at both the felony and misdemeanor levels. In California, diversion is an official disposition that occurs prior to the trial and involves a special proceeding, governed by legislation passed in 1972. The district attorney determines when the diversion provisions apply to the defendant and must advise the defendant and his or her attorney in writing of such a decision. The eligibility of the defendant is restricted by the nature of the drug-involved offense, by what violations to certain codes have occurred, and in what combination with other offenses. By law, defendants must meet the six requirements outlined in Penal Code chapter 2.5, "Special Proceedings in

Narcotics and Drug Abuse Cases'' article 1000, subdivision (a):

-

The defendant has no conviction for any offense involving controlled substances prior to the alleged commission of the charged divertible offense.

-

The offense charged did not involve a crime of violence or threatened violence.

-

There is no evidence of a violation relating to narcotics or restricted dangerous drugs other than a violation of the sections listed in this subdivision.

-

The defendant's record does not indicate that probation or parole has ever been revoked without thereafter being completed.

-

The defendant's record does not indicate that he or she has been diverted pursuant to this chapter within five years prior to the alleged commission of the charged divertible offense.

-

The defendant has no prior felony conviction within five years prior to the alleged commission of the charged divertible offense.

Drug diversion was intended for those users of illicit drugs who are, as one probation officer said, "not immersed in the drug culture; it's for the recreational users. . . ." Illicit drug traffickers or those suspected of heavy selling activities are considered to be too far along—both in their criminal activities and in the amount of drugs they are suspected of using-to be candidates for diversion.

A defendant may attempt to qualify for diversion by self-enrolling in a treatment program, but more often the court or the defense attorney initiates the action by requesting that the district attorney begin eligibility proceedings. The case is always referred to the probation department where the defendant's suitability for education, treatment, or rehabilitation is assessed. This assessment is provided in written form and is called the presentence investigation report. Sometimes the presentence report discloses information such as prior convictions for certain offenses or a record of a failed probation that renders the defendant ineligible for diversion. All of the county's reports are handled by one section of the probation department and contain the probation officer's findings, which are presented to the court with a recommendation. The district attorney must agree to the diversion disposition, but the court makes the final determination regarding the terms of the release. The period during which further criminal proceedings against the defendant may be diverted is no less than six months and no longer than two years. Progress reports are filed by the probation department with the court no less than every six months.

Although the box marked "Diversion" in Figure 1 is the official point

at which it is noted by the court, activity toward this disposition begins soon after the arrest is made. The defense or prosecuting attorney may request continuances from the court to forestall the date of arraignment to allow time for the probation department to conduct its investigation. If the court does not deem that the defendant would benefit by diversion, however, or if the defendant does not agree to participate, the proceedings continue as in any other case. Trial may be by court or by jury; both have the power to dismiss, acquit, or convict. A conviction results in another hearing to deliver the sentence, which may include but is not limited to (1) a jail term; (2) a jail term and a fine; (3) a jail term, a fine, and probation; (4) a fine only; (5) probation only because of a suspended jail term; or (6) a jail term and probation.

Terms of incarceration may be served at the main detention facility, at a minimum security facility, or at a work furlough station. It is possible to be sentenced to a jail term without probation and to apply for it while in confinement. Terms of probation may include drug treatment. Both diversion and probation are pathways out of the criminal justice system into the drug treatment system and are considered in detail in the next section.

Diversion and Probation: Pathways to Treatment

This section focuses on pathways to treatment through the criminal justice system and the implied transfer of criminal justice functions to other social institutions such as drug treatment programs. Although they may be described as "systems," there are few clearly delineated policies that govern the overlap of criminal justice and drug treatment activities and how clients are "shared." Each system must be thought of as being its own freedom within the county, and each operates accordingly. Each has its own mandated mission, budget, hierarchy, and governing philosophy, which has relevance both internally and as it views its place in the total county system.

Diverted criminal justice "clients" and those on probation have increasingly found themselves enrolled in drug treatment facilities, outpatient programs in the community, or some alternative program (such as Narcotics Anonymous meetings or group therapy) in lieu of incarceration. The types of offenders involved in such programs may range from those arrested for possession of small amounts of controlled substances to those charged with offenses in which drugs are not officially specified as part of the offense. The latter type of offender is considered to have a problem with drugs that is specifically linked to his or her crime (e.g., shoplifting,

reckless driving, wife-battering, burglary).

Both informal and formal mechanisms allow for these alternative dispositions. Informally, private attorneys or public defenders may contact treatment centers to arrange for a possible placement prior to sentencing, thereby supporting to the court their argument for a lighter sentence. Probation officers may refer someone to a treatment agency, and a shorter probationary period may result. Sheriffs working in the jail, along with the substance abuse mental health worker, may evaluate whether those inmates already convicted are suitable for early release into a treatment program as part of probation in lieu of continued incarceration.

Operationally, probation cases and diversion cases are handled by the same officers through the same department and are subject to similar conditions. Diversion is a process of extrication from the criminal justice system; in that sense, probation is a form of diversion because it entails a less restrictive disposition than straight jail time. The main difference is that diversion occurs before sentencing and probation occurs afterward. Therefore, successful completion of the former means the record of arrest may be expunged. Probation is a sentence arising from a conviction that may come after or in lieu of jail. If it is violated, the person may be rejailed immediately as well as arraigned on the charge that precipitated the violation, which is carried over (see Figure 1 for a graphic view of this process).

Probation departments and public defender offices provide positions for resource officers who are assigned to locate alternative placements for divertees and convicted misdemeanor offenders whose problems are viewed as drug related. Pretrial drug diversion programs consist mainly of supervising an arrestees participation in a treatment program. People who have spent time in jail are sometimes released directly into a residential program in the community, with resource officers again providing the coordination.

These long-standing, informal approaches to sentencing have been supplemented in California by structured arrangements in the criminal justice system. The California Penal Code provision permits a civil procedure for the diversion of certain arrestees prior to sentencing, with local jurisdictions deciding whether and how to implement such activities (see Appendix A for the text of Penal Code section 1000). Such programs suspend prosecutorial action and eventually result in the dropping of charges if an appropriate program is completed to the court's satisfaction.

The Penal Code contains provisions that specifically prohibit the applicability of drug diversion to (1) defendants who have had prior convictions for any offense involving controlled substances; (2) defendants whose offense involved a crime of violence or threatened violence; and (3) defendants who have violated parole or probation in the past. Moreover,

diversion can be employed for only a limited number of the Penal Code violations that involve controlled substances.

Table 1 shows reported numbers of arrests by charge for drug law violators in the county during 1986, 1987, and 1988. It also provides the same information in percentages. Felony-level arrests for drug law violations account for a larger percentage of total arrests for all felony charges each year, with charges for dangerous drugs and narcotics showing the greatest increase. Misdemeanor-level arrests for all drug law violations account for only slightly more of the total misdemeanor arrests over the three years; despite the percentage of those arrested for "all other drugs" nearly doubling between 1986 and 1988. Both felony-and misdemeanor-level arrests for marijuana decreased, whereas the number of women arrested for all felony-and misdemeanor-level drug law violations increased. Felony-level arrests for drug law violations accounted for an average of 27.6 percent of all felonies over the three years; misdemeanor-level arrests for drug law violations accounted for an average of 9.3 percent of all misdemeanor arrests during that time.

In the study county for 1986, 842 people were officially diverted; in 1988, 1,786 people were officially diverted, but it is not known how many of these were diverted specifically for drug law violations. Diversion is now an option for a variety of charged offenses, including writing checks with insufficient funds, domestic violence, child abuse, and child sexual abuse, and for offenses committed by mentally retarded people. Data that differentiate among the cases are not easily accessible.

People diverted under all diversion laws, including those charged with drug law violations, become the responsibility of the probation department. Officers use the presentence report and an interview with the person to determine what sort of program is appropriate. A variety of programs are accepted by the probation department as sufficient for the conditions of release under this law, including nondrug treatment programs. Sometimes the person returns to his or her home in another jurisdiction and participates in a program outside the county while keeping in touch with the probation department. Outpatient individual or group therapy is also acceptable but is rarely used because of the cost involved. Regular participation—daily, weekly, or less often—in Narcotics Anonymous or another appropriate 12-step Anonymous group is also a standard disposition.

The majority of drug diversion clients, however, participate in the probation department's own diversion class, which is held for three hours at a time during six consecutive weeks. The curriculum of the class is didactic. A probation officer who teaches the course said some time is spent on issues surrounding illicit drug use and dependence, but the bulk of the time is spent on the legal ramifications of continued use: "We want

TABLE 1 Reported Information for Drug Law Violations by Level of Charge and Year in Number and Percentage of Adults Arrested

|

|

1986 |

1987 |

1988 |

|||

|

Level of Charges |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

Felony-Level Charges |

||||||

|

Arrests for marijuana |

248 |

123 |

174 |

7.9 |

213 |

75 |

|

Arrests for dangerous drugs |

596 |

29.7 |

688 |

31.2 |

813 |

28.8 |

|

Arrests for narcotics |

1,143 |

56.9 |

1313 |

59.6 |

1,761 |

62.4 |

|

Arrests for all other drugs |

21 |

1.0 |

28 |

13 |

32 |

1.1 |

|

Male arrests for all drug law violations |

1,673 |

83.3 |

1,774 |

80.5 |

2,270 |

80.5 |

|

Female arrests for all drug law violations |

335 |

16.7 |

429 |

19.5 |

549 |

19.5 |

|

Total arrests for all drug law violations |

2,008 |

26.6 |

2,203 |

26.8 |

2,819 |

29.3 |

|

Total arrests for all charges |

7,557 |

23.9 |

8,215 |

24.7 |

9,603 |

28.4 |

|

Misdemeanor-Level Charges |

||||||

|

Arrests for marijuana |

365 |

16.0 |

374 |

18.2 |

369 |

14.7 |

|

Arrests for glue sniffing |

7 |

.993 |

6 |

.003 |

3 |

.001 |

|

Arrests for selling/trafficking |

1,561 |

68.4 |

1,248 |

60.6 |

1,353 |

54.0 |

|

Arrests for all other drugs |

349 |

15.3 |

430 |

20.9 |

778 |

31.1 |

|

Male arrests for all drug law violations |

1,995 |

87.4 |

1,789 |

86.9 |

2,170 |

86.7 |

|

Female arrests for all drug law violations |

287 |

12.6 |

269 |

13.1 |

333 |

13.3 |

|

Total arrests for all drug law violations |

2,282 |

9.4 |

2,058 |

8.2 |

2,503 |

10.4 |

|

Total arrests for all charges |

24,063 |

76.1 |

24,990 |

75.2 |

24,154 |

71.5 |

|

Felony-and Misdemeanor-Level Charges |

||||||

|

Total arrests for all drug law violations |

3,955 |

13.5 |

4,261 |

12.8 |

5,322 |

15.7 |

|

Total arrests for all charges |

31,620 |

100.0 |

33,205 |

100.0 |

33,757 |

100.0 |

|

Source: State of California Department of Justice, Sacramento, Calif., 1986, 1987, and 1988. |