The Market for Drug Treatment

Richard Steinberg

Medical care is not an ordinary purchase. The purchaser hires someone else (typically, a doctor) to tell him or her what to buy. Most of the risk is borne by the patient—payment is not contingent on the success of the treatment. Payment for services may be prospective or retrospective and is often the responsibility of third parties (insurers or government), although responsibilities are often shared by the purchaser (through copayments, deductibles, caps, restrictions on eligible providers, and restrictions on covered services) and the general public (financing the implicit tax expenditures on employer-financed health insurance and on the medical deduction from personal income taxes).

Within this unusual market, the market for treatment of drug problems is unique. In many cases (and in all of the cases considered here), the purchase of drug treatment is a direct response to criminal activity by the customer, although not all customers are charged with this crime. Sometimes the purchase of treatment is voluntary, although it is commonly coerced, either implicitly (through threats of prosecution for possession or loss of employment) or explicitly (as a court sentence). When the service is purchased voluntarily, we have what Winston has called an "anti-market" in which people pay to not consume something.1 Ideally, the service would change the addict's preferences for drugs, but this is not easy to accomplish. (The best minds on Madison Avenue were unable to change our preferences regarding the "New Coke," a much easier task than changing preferences for an addictive substance like cocaine.) Realistically, we must measure success more by our ability to minimize the social side effects of drug addiction than by our ability to conquer the addiction itself. For most illnesses, society has considerable sympathy for the victim. Sometimes the reason for this feeling is obvious, as when the onset of illness is completely

Richard Steinberg is in the Department of Economics, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

outside the victim's control. We have sympathy for older victims of lung cancer, even though their smoking may be the cause of illness, because they became addicted to cigarettes before they knew of the risks. Society's sympathies for the younger victims of lung cancer (who know about the risks they run) and for alcoholics are mixed, but there appears to be a near consensus against sympathy for drug addicts. The limits of public compassion are tested by calls for public subsidies for drug treatment. If such programs are to pass political muster, the case for them must be made in terms of benefits to nonaddicts.

This paper concerns the market (supply and demand) for drug treatment. Alcohol, tobacco, nasal spray, and other legal "drugs" are beyond the scope of this study. Only the market for treatment of drug problems is covered; the market for drugs themselves is not considered except insofar as treatment interacts with this market. After briefly surveying some relevant facts, the paper presents rationales for public intervention and a framework for policy analysis. A later section discusses the effects of various policies on market equilibrium, considering the interrelated markets for treatment and insurance coverage and some difficulties in empirical application. The paper concludes with a discussion of policy options to enhance supply, policy options to enhance efficiency, and policy options in the insurance market.

THE FACTS

More than 1.8 million Americans have received treatment for drug or alcohol abuse or dependence (both referred to here as addiction) out of a population of addicts that is undoubtedly larger.2 There are three major types of treatment: inpatient, residential, and outpatient. Treatment modalities include detoxification, maintenance, and drug-free outpatient.3 Facilities are provided by the government and the for-profit and nonprofit sectors.

Addicts utilize many sources to pay for treatment. The federal government assists through Medicare and Medicaid. Eligibility for the medically indigent under Medicaid differs by state, and not all states cover such treatment. A sliding-scale fee structure is typical. State and local governments provide most of our nation's treatment, available to the poor at no charge or at steeply subsidized rates. Nonprofit hospitals (and, to a lesser extent, for-profit hospitals) accept a limited number of patients on a charity basis.

Medical insurance plans historically have played only a minor role in financing drug treatment, but this pattern is changing. Spurred on in part by state mandates,4 66 percent of health care insurance participants (a

group that comprised 95 percent of the nation's employees) in the private sector were covered for drug treatment in 1986. Coverage was even higher for state and local government employees. In 1987, 86 percent of participants (93 percent of employees were participants) were covered for drug treatment.5 Finally, the proliferation of drug testing has been accompanied by a concomitant increase in the demand for treatment as a first step remedy for positive test results. This trend is of growing importance, for, in 1987, 30 percent of the Fortune 500 companies screened employees for drug.6

Many of those who seek treatment do not do so voluntarily. Various sources indicate that perhaps 25 to 35 percent of patients are under court orders to seek treatment, and another 25 to 35 percent are implicitly coerced, seeking treatment after arrest but before sentencing. The remainder are self-referred, although many of these individuals have been heavily pressured by employers, friends, and family.7

RATIONALE FOR PUBLIC INTERVENTION

Welfare Economics and the Pareto Standard

No doubt it would be pleasanter to live in a world with less drug addiction, but from this fact we cannot automatically conclude that public intervention is warranted. Resources are scarce and social needs boundless. The subdiscipline of welfare economics is dedicated to determining when unregulated markets are optimal in the face of scarcity and when public diversion of limited resources to a particular need is worth the opportunity cost.

A state of the world (denoted an economy) can be described by the quantities of each "good" affecting each person. A "good" is defined as anything the consumer cares about, including nontraded values such as good health or freedom from crime. One economy is said to "pareto-dominate" another if no individual prefers the second economy and at least one individual prefers the first. (This definition derives from Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto.) Thus, pareto-dominance is established by unanimous preference. An economy is said to be pareto-optimal if it is feasible and not pareto-dominated by any other feasible economy. There are, in general, an infinite number of pareto-optima to choose from, and they differ in the distribution of real income.

Most economists would agree that the best economy is one of the pareto-optima (although there is no consensus on which one). The reason is simple: if an economy is not pareto-optimal, there is a feasible alternative that would make at least one person (more likely every person)

better off without hurting anyone. Since the days of Adam Smith, it has been well known that when all goods are traded in competitive markets, the outcome is pareto-optimal (nowadays, this is known as the first fundamental theorem of welfare economics). Thus, when markets are complete and competitive, the only case for government intervention is a distributional one; society might prefer an alternative pareto-optimum containing a different distribution of income. When markets are incomplete or noncompetitive, there is a (rebuttable) presumption that the market is not pareto-optimal, establishing a prima facie case for governmental intervention.

There are many reasons to doubt the applicability of the first theorem to economies containing drug addicts. First, the notion of consumer sovereignty underlying the pareto standard is debatable here. Second, markets are not complete. Relevant markets for trading certain side effects of addiction and for trading information do not exist.

Addiction and Consumer Sovereignty

Economists are, with just cause, reluctant to prescribe what is good for a person. Generally, a person's own ''revealed preferences" are taken as data so that any change in consumption resulting from an enlargement in an individual's choice set (the set of feasible combinations of goods) is regarded as proof of betterment. This reverence for consumer sovereignty is natural when consumers are well informed and preferences are stable. Furthermore, economists are typically wary of social decisions to overrule individual preferences, for they fear that such decisions open the door to the worst kind of paternalistic excess.

Psychologists, on the other hand, study the reasons why people do not do "what is best for them." The "medical need" paradigm overrules individual preferences entirely, replacing them with a determination by physicians of the amount of care a person should have to obtain the highest state of health possible within the constraints of current medical knowledge.8 Despite these objections, most economists remain unpersuaded that the state can do better than individuals in determining what is good.

In cases of drug addiction, the economists' presumption is confronted with its severest test. First, consider the diversity of preferences evidenced by an addict who asks you to lock him up until he "kicks" the habit. This addict is, in effect, asking you to reduce the size of his choice set, indicating that he does not now want to enjoy the consumption that would be revealed if he were later unconstrained.

Economic theories of addictive behavior fall into two general cate-

gories. Theories of "rational addiction" assert that decisions to consume drugs or kick the habit are made by individuals with stable preferences and full knowledge of the future consequences of their consumption decisions.9 In such a setting, drug addicts may regret the circumstances of life that have caused addiction to be their "best" option, but they would never regret the choices they have made (given the circumstances). Theories of "multiple personality" assert that consumption of addictive substances alters the addict's preferences among goods, in effect making them into another person.10 Prospective addicts may consider the impact of their choice on "the person they will become,'' but the theories differ as to how they make decisions and whether they will ever regret the decisions they have made.

None of the theories developed so far is fully comprehensive, but each can explain some observed aspect of addictive behavior. For example, Becker and Murphy's (1988) "rational" theory is the only one to explain why some addicts voluntarily undertake a "cold turkey" approach in their attempt to kick their habit. In contrast, Becker and Murphy's model cannot explain the pain of addicts who wish they could quit but cannot, or the behavior of the addict who wants you to lock him in a room until he has fully withdrawn. Some sort of "multiple personality" theory appears to be necessary to rationalize these aspects of behavior.

The application of these theories to policy questions remains underdeveloped, but some conclusions emerge. The "rational addict" would always prefer a gift of public money to an equal-sized public subsidy for drug treatment. Because addicts always do what is best (in terms of their own values), they will put money to its best use. If they are ready to kick the habit and want to purchase help in doing so, they can use their cash grant for treatment. But many addicts will prefer to use the money in other ways, ways that bring them greater satisfaction. Thus, the case for public subsidy of treatment cannot rely on the addict's self-interest (as self-defined) if addicts are "rational."

A different conclusion emerges from some (but not all) of the "multiple personality" theories. A single physical person must, at various times, consider the interests of four "psychological people"—the potential addict, the potential person the consumer would be if she avoids addiction, the actual addict, and the reformed addict—each of which has different preferences that must somehow be reconciled. It is quite possible that the reformed addict will prefer a subsidized (or even coerced) treatment program over an equivalent sum of money, although during addiction the same person would feel differently. A self-interest case for subsidized treatment can emerge from such a model.11

One could argue that addicts are not perfectly informed; thus, their choices do not maximize their well-being. If they were fully informed of the consequences of drug addiction, one could conjecture that many would

be willing to quit or, at least, not start. There is probably some (but not much) truth to this assertion: some addicts are suicidal, others value the experience of drug consumption very highly, and both groups would not change their behavior even if they were better informed. If it were only an informational problem, public education programs would be the obvious solution. If we knew for certain that each addict would want to quit if fully informed of the consequences, and that educational programs were expensive or ineffective at informing addicts, then a coerced treatment program would more efficiently serve the addict's self-interest. As a practical matter, however, this rationale is unpersuasive and overly paternalistic.

One could justify intervention by rejecting the principle of consumer sovereignty as it applies to drug addiction. Society can continue to care about the well-being of each of its citizens but still reject the notion that drug addicts are the best judges of their own well-being. Drug treatment may be a "merit good"—a good that addicts systematically undervalue. The problem with such an approach is the same: where does such paternalism stop? Should society reject the self-valuations of skiers, Democrats, or listeners to disco music?

A valid distinction could, perhaps, be drawn in the case of addictive drugs. We might reject self-defined interest whenever behavior leads to objective decreases in physical well-being.12 If we accept the "multiple personality" theories of addiction, we could draw a finer distinction. Consumer sovereignty is not as well defined—which personality is the one whose interests society should protect? Society need not accept the individual's resolution of this conflict. We could reject the self-defined interest of the addict in favor of the self-defined interest of the rehabilitated addict on grounds of objective physical well-being. Is it really paternalistic if the former addict will thank us someday for interfering with his previous preferences?

Another way society could decide which of the many consumer preferences possessed by an individual it wished to respect is to use the legal concept of duress. Decisions made under duress are legally suspect. Thus, if we lock an addict up (at his own request) until withdrawal is complete, we are not violating consumer sovereignty even if he begins to protest his incarceration. Withdrawal causes duress; his protests are suspect and should not be respected. One could extend this argument further, although it becomes less persuasive in extension. Once addicted, the addict's decision to continue using drugs can be regarded as one made under duress, considering that contemplation of withdrawal is quite stressful in itself. Under this theory, we would be justified in locking up an addict until withdrawal were complete even if the addict did not request such an action.

In summary, it is difficult to construct a case for public subsidies or coerced drug treatment based on the addict's own interest, for paternalism sets a dangerous precedent. However, addictive behavior raises unique doubts about the consumer sovereignty standard, and it may be possible to draw fine distinctions allowing limited rejection of this standard. Ethical doubts about the wisdom of such a policy will remain; the case for public intervention can more soundly rest on the interests of nonaddicts in controlling addictive behavior, to which the discussion now turns.

External Effects of Drug Addiction

An "externality" is an effect of market transactions (production, consumption, or trading activities) on third parties who do not control the transaction. For example, when one consumer purchases electricity from a power company, other consumers are forced to consume the resulting air pollution. When externalities affect only prices (denoted a pecuniary externality), they are not pareto-relevant, but when a market transaction directly affects the well-being or productivity of others (a technological externality), there is a presumption in favor of governmental intervention. Technological externalities generally cause a departure from pareto-optimality 13 so that governmental intervention has the potential to help some individuals and hurt no one.

Drug addiction causes a variety of external costs. Thus, when drugs are not illegal or otherwise regulated by government, we can expect addiction rates to be excessive. The exact sense in which it would be excessive is that the benefits to third-party victims from a cutback in drug consumption would exceed the (self-perceived) loss to addicts, so that, with suitable compensation, everyone's lot could be improved. 14 Some drug addiction remains in a pareto-optimum, but there would be less addiction than in an unregulated market.

If drug addiction causes external costs, then drug treatment causes external benefits. Thus, in a free and unregulated market, we would expect to see too little drug treatment, and some sort of subsidy may be warranted.

Some of the external effects of drug addiction are well known, although the extent to which they occur remains understudied. Addicts commit property crimes to finance their habit. Their demand for illegal drugs creates a market in which drug traffickers use force and fraud to maintain monopoly power and reduce the threat of prosecution. Some drugs cause violent and antisocial behavior. Moreover, drugs can affect reaction time and judgment, leading to auto accidents, airplane or railroad crashes, and on-the-job injuries and fatalities. Drug consumption can also

lead to unemployment and consequent receipt of public support, financed through distortionary taxation.

The control of contagious diseases has external benefits, and perhaps drug treatment is a similar case. When one individual is vaccinated, that individual helps others (by reducing the chance that the disease will be transmitted) as well as herself. Drug addiction appears to be similar, for addicts often support their habit by "pushing," initiating new users and later profiting by supplying them with drugs. In addition, drugs can spread in a clique through social pressures on nonusers.

Although the contagion model has considerable descriptive appeal, there is a relevant distinction from the perspective of externality theory. It is one thing to catch a disease from an unvaccinated carrier (who evidences no signs of the disease); it is quite another to decide voluntarily to start using drugs after interacting with another drug user. Unless new users are coerced or fooled into using the drug until they are addicted (as in allegations of spiked candy or ice cream), they are party to a market transaction and not victims of an externality. However, nonusers who are concerned about such external effects as crime are clearly made worse off every time there is a new user. From this perspective, contagion is not itself an externality, but it interacts with and worsens other externalities that result from drug addiction.

The "multiple personality" theories of addiction suggest an alternative rationale in which contagion is directly the source of an externality. One facet of the personality is unable to resist temptation and consequently consumes drugs whenever surrounded by other users. Another facet wants to avoid becoming an addict at all costs but is unable to control the behavior resulting from the first facet. This second facet, if it is regarded as a separate person, is externally affected by contagious drug consumption. Unable to refrain from drugs when temptation presents itself, this physical person may vote for laws restricting drug availability and encouraging treatment of others in order to avoid temptation.

Intravenous (IV) drug users are thought to be the major vector for the spread of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) into the heterosexual population. Although the rationality or education of those sharing needles can certainly be called into question, there is no externality issue among IV drug users: each needle sharer is directly transacting with another needle sharer, and the transaction is purely voluntary. However, if one needle sharer knew he were likely to have AIDS and concealed this information from someone sharing the needle, there would be an informational externality. Here, there is no direct transaction between the parties on the important, good "information." The same analysis applies to interactions between needle sharers and nondrug-using sex partners. There is no externality without informational asymmetry, for the informed sex

partner is the final link in a chain of voluntary transactions. Informational asymmetry is, however, quite likely here.

Finally, intervention in the drug market may be warranted to reduce statistical discrimination. Statistical discrimination occurs whenever employers are unable to ascertain the qualities of potential employees and so judge them by the average characteristics of the potential employee's ethnic or social class. Employers, unable to ascertain the drug status of potential employees, may discriminate against urban youths and ethnic groups that are thought to contain a greater proportion of addicts. When these groups are employed, it is at a lower wage to "compensate" the employer for the risk he is taking.

Drug use by some members of an ethnic class has external costs for other members of that class who will be victimized by statistical discrimination. Such use may have beneficial externalities for other ethnic groups, who will be in high demand if their perceived drug use is low. However, one set of externalities cannot simply be cancelled against another—inequity is due to variation and not averages. Furthermore, the average quality of job matches (that is, whether the right worker will be employed in the right job) is degraded because of discrimination resulting from drugs. As a result, overall productivity will suffer.

In summary, it is very difficult to construct a rationale for intervening in the drug treatment market based on the interests of the addict. If we really want to make the addicts better off (in their own judgment), a gift of money is far superior to a subsidized or coerced treatment program. One can argue that addicts do not know what is in their own best interest, but there are dangers in the paternalistic overruling of anyone's preferences. Moreover, it is difficult for an outsider to determine whether a particular addict is unable to act in his own interest, for observations of addiction are always consistent with a "rational" model. Yet even if there is no interest in regulating addiction for the addict's sake, there is a clear rationale for intervening in the drug treatment market. Rational addicts ignore the harmful side effects of their addiction on others. Public intervention is justified to reduce these externalities.

Some Welfare Economics of Insurance

Some goods are regarded as valuable simply because consumers desire them, and economists have little to say about such preferences. Other goods are desired as means to an end. It is most common to regard insurance as one such good. Insurance reduces the expected utility loss resulting from environmental uncertainty. The value of insurance thus depends on the individual's tastes (risk aversion) and the level of

uncertainty.15

At the individual level, it is unclear why drug treatment insurance should have value. Whether or not we regard addiction as a disease, the initial choice to consume drugs is clearly under the control of the consumer so that environmental uncertainty is minimal. Indeed, there appear to be only three sources of uncertainty. First, there is uncertainty about whether (and how quickly) consumption will result in addiction. A consumer planning to try cocaine just once might wish to purchase insurance to cover the possibility that he might become instantly addicted and need expensive treatment to stick to his plan. Second, there is uncertainty about future needs for treatment. A consumer may rationally decide to indulge and have no plans for treatment to kick the habit but may be wary about the possibility of being caught and ordered into treatment. Insurance thus reduces the financial consequences of the random event "getting caught." Finally, there is uncertainty about future choices. A young nonuser contemplating an insurance purchase may be uncertain about whether his tastes will change in the future and lead to drug use. Alternatively, he may believe he has stable tastes but is currently avoiding drug use because of the high current price. He is uncertain whether the future price will fall sufficiently to induce him to consume at some time in the future.

It is questionable whether most of the people who consume drugs worry very much about any of these possibilities. Many consumers would entirely discount the possibilities of becoming addicted or getting caught using drugs. Some are present oriented and neglect the future almost entirely. Some are oblivious to financial consequences, which would largely fall on others (their parents, their creditors, etc.). Many have low self-esteem and feel little desire to protect themselves against future consequences. Thus, the private value of insurance appears to be minimal.

The fact that drug consumers have little demand for insurance does not imply that they have little demand for insurance policies. An addict who knows she wants to purchase treatment would wish to purchase an insurance policy to reduce her treatment price. There is no reduction in the consequences of uncertainty here, merely an income transfer. Insurance companies seek to avoid writing such policies, but as a practical matter, they cannot entirely avoid this occurrence. The key distinction in terms of welfare economics is that pure insurance is automatically pareto-improving (if the seller of insurance is less risk averse than the buyer or is able to pool risks), whereas insurance policies need not be. In this case, insurance policies are probably pareto-improving even though they do not provide pure insurance because the income transfer encourages the consumption of treatment and this reduces external costs suffered by those making the transfer. Many health insurance policies are purchased for a

group—either a family or a set of employees. A family head might wish to purchase insurance to protect the family from the consequences of a choice by one of the other members to consume drugs. The key distinction here is that the family head regards drug use by others as a stochastic event with external consequences for the rest of the family.

Employers might wish to provide drug insurance for employees because of pecuniary externalities. When an addict receives treatment, future health care costs may be reduced. Indeed, it has been argued that the reduction in this patient's future health care costs would more than cover the cost of addiction treatment.16 If this is so, then the firm's overall costs of insurance are reduced, allowing it to purchase more insurance or offer higher salaries for other employees or to increase the wealth of the owners of the firm. Thus, treatment of one addict has external benefits (mediated through the price system) on other employees and stockholders.

The externality in this case is pecuniary, not technological. Thus, this externality provides no basis for state intervention (such as mandated or subsidized coverage). In competitive equilibrium, insurance firms would offer drug treatment coverage to firms at a rate lower than the direct costs of treatment, and the optimal quantity of coverage would be purchased.17 The incremental cost of drug treatment coverage would be set equal to the incremental aggregate health care costs (which may be negative). If drug insurance more than pays for itself (as alleged), insurance rates would be lower for those employers who provide such coverage.

There is another reason why drug treatment insurance may be of value to employers. Few employers wish to hire addicts, but one cannot be sure at the time of hiring whether a particular employee is or will be an addict. Once addiction is discovered, it may be cheaper for the employer to pay for treatment than to fire the worker, for recruitment and training costs are substantial and on-the-job experience enhances productivity. Insurance thus brings the usual gain in expected utility by reducing financial risk, but this gain accrues to the owners of the firm rather than the insured party.

Yet the story is even more complicated because both parties have some bargaining power when employee drug addiction is discovered. The employee has bargaining power because it would be expensive to replace him. The employer has bargaining power because an untreated but experienced employee may be worth less than a raw recruit; consequently, the firm can credibly threaten to fire the addict if he does not seek (and personally pay for) treatment. Although the author knows of no formal models of this bargaining situation, it would seem that drug insurance with some sort of cost sharing, either explicit (such as copayment) or implicit (salary reductions or deferred raises), would emerge.

There is a subtler reason for employee provision of drug treatment coverage. It is difficult for employers to observe the individual productivity

levels of each worker, and it is also difficult to observe drug addiction. If drug addiction reduced worker productivity and the firm had a policy of firing known addicts, then the worker would have an incentive to hide addiction as long as he could. During this period of hiding, the firm's productivity would suffer. If, instead, the firm subsidized treatment (through purchase of appropriate insurance or directly) and provided assurances of confidentiality, the worker might tend to come out of hiding earlier and firm productivity would be enhanced.

Given that insurance has value from a social welfare viewpoint, the question remains as to the optimal structure of insurance contracts. Insurance provides highly nonlinear reimbursement, with deductibles, copayment, ceilings, indemnities, and limits on reimbursable services and providers. Copayment, indemnities, and restrictions on reimbursable services make sense as second-best corrections for moral hazard (the tendency of an insured to consume more services than he would if personally liable for the full costs), and deductibles make sense because the consumer undertakes only a small risk in order to economize on "loading" (administrative expenses by insurers). It is difficult, however, to understand the welfare value of ceilings.18 Some recent progress has been made19 but it is fair to conclude that a great deal remains to be done.

The issue of moral hazard is more complex when treatment has external benefits. Moral hazard causes individuals to consume more treatment than in their "private optimum," but this is precisely what we want addicts to do because treatment produces external benefits. Individual insurance companies would not obtain the full external benefits resulting from treatment, so they would continue to offer policies with copayment. There would be less copayment in a socially optimal system of insurance, with the optimum depending on the magnitude of external benefits and the responsiveness of addicts to the price of treatment.

Realistically, we cannot accurately estimate the socially optimal copayment rate. A law banning copayment for drug insurance policies would probably move us closer to optimality and seems like a sensible approach. However, the issue is complicated by two additional considerations: other sorts of moral hazard and reduced policy availability.

The reduction in the price of treatment caused by the elimination of copayment would not be restricted to externally beneficial services. The patient might devote expenditure increments to increased comfort during treatment (such as upgrading to a country-club type of residential facility) rather than more effective treatment, a clear moral hazard problem. But the chief problem for many addicts is inducing them to seek treatment in the first place, not inducing them to increase the amount of their treatment. Increased patient comfort would generate external benefits if it led more addicts to seek initial treatment, mitigating the moral hazard.

Because neither the insurer nor the employer would obtain the full external benefits of treatment, elimination of copayment would require governmental coercion. In response, insurers might withdraw from the drug addiction coverage market. Government mandates could eliminate this problem if they required maintenance of a drug addiction coverage option in all health insurance offerings. However, employers would purchase a suboptimal quantity of this option, ceteris paribus. Thus, mandating elimination of copayment is not a sufficient policy to induce optimal drug addiction coverage. Policy options with respect to insurance are discussed in greater detail in a later section.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Externalities may establish a prima facie case for governmental intervention, but a great deal more information is required if government is to determine the proper form and magnitude of intervention. Cost-benefit analysis, properly done,20 provides a complete guide to policy choice. It provides a set of techniques for processing information so as to choose the policy that leads to the best combination of fairness and pareto-improvement.

Externalities provide the principal source of departure from optimality, so the most critical data need is to determine the value of a reduction in the external effects of drug addiction. Having established that value, the next step is to establish the links between drug treatment options and the size of external effects following treatment. Finally, one must link the scale of treatment to public policy options, such as subsidies to clinics, tax breaks for treatment, or mandated insurance coverage for drug treatment.

The first link in that research chain is by no means an easy one. By definition, relevant externalities are not bought and sold, so there is no direct evidence from the market that reveals the value of a drug-free environment (or the cost of a drug-threatened environment) to nonusers. Economists have developed two techniques for determining the value of nontraded activities (i.e., relevant externalities): the hedonic and contingent valuation methods.

Hedonic studies use statistical techniques to take advantage of information from trading activities.21 Although no one buys "a drug-free environment" directly, varying quantities of this good are implicitly purchased as part of a package deal when nonusers decide where to live. Hedonic analysis attempts to determine what portion of the variation in price of the composite good (in this case, housing) is due to variation in each of its characteristics (size of the house, number of bathrooms, drug

addiction rate in the neighborhood, quality of neighborhood schools, etc.). From this information, a demand curve for a drug-free environment can be estimated. This curve indicates the nonuser's willingness to pay for each possible level of the constituent characteristic of interest.

There appear to be no hedonic studies that estimate the value of a drug-free environment, but it might prove both feasible and useful to sponsor some. Feasibility depends on the availability of data on drug usage rates (or some reasonable proxy for them) by neighborhood. In conducting the study, the investigator should be careful not to overcontrol for confounding characteristics. For example, one would want to remove the confounding effects of house size on property values from the analysis by introducing an appropriate control variable, but the effects of variation in the crime rate should not be removed because one of the reasons people are willing to pay to avoid high-addiction communities is to avoid crime.22

One problem with the hedonic approach is that some of the externalities caused by drug addiction spill over neighborhood boundaries. Commuters, shoppers, and tourists who pass through a high-addiction community can be victimized by crimes committed by addicts, but their discomfort would not affect property values in the high-addiction community. 23 Thus, we could not estimate the value of reductions in these externalities from variations in property values. Nonetheless, a hedonic analysis would be an important first step and place a lower bound on the value of control.

The contingent valuation technique employs sophisticated survey instruments that attempt to compensate for the respondent's lack of knowledge and to provide incentives for the truthful and thoughtful revelation of preferences.24 Although an improvement on simpler survey instruments, the method is still subject to the vagaries of responses to hypothetical questions. However, unlike the hedonic method, the contingent valuation technique can provide an estimate of the value of controlling those externalities that spill over community boundaries. Furthermore, the technique can supplement the imperfect evidence provided by the hedonic method.

In conducting valuation studies of any sort, four things must be kept in mind. First, the benefits of externality reduction are not necessarily a linear function of the extent of drug addiction. The benefits may depend on the share of users in the population rather than the number, and there may be thresholds beyond which the problem becomes exponentially worse. Second, the benefits depend as much on characteristics of nonusers as on the characteristics of users. A study that only examined the effect of treatment on the addict without considering the environmental response would present a very incomplete picture.

Third, there are many ways of reducing the external harm wrought by drug addicts. Certainly, one way to do this is to treat the addiction, and one would want to know the success rate and cost of treatment programs. Again, in measuring the success of a drug treatment program, we should consider the extent of externality reduction, not just the ''cure'' rate. But if treatment programs are not very effective or are very expensive, alternative solutions (which reduce the external effects of drug addiction without attempting to cure the addiction) may be more efficient. Although a discussion of these alternative policies is beyond the scope of this paper, it is clear that precise estimates of the monetary-equivalent value of treatment programs are required to determine the superior policy option.

Finally, there may be interactions between the success of treatment and the policy option that led the user to seek treatment. One reason is what may be called Freudian effects. Freud argued that when patients have to pay for psychotherapy, they work harder at getting better. If this principle applies to the drug treatment market, then programs that subsidize patient costs are less effective then alternatives. Another possible example stems from policies to make treatment facilities more inviting for those voluntarily seeking treatment. Although such policies may be effective in increasing the share of the addict population seeking treatment, they may also reduce the long-term effectiveness. Patients who have been through such programs may be more likely to suffer relapses, feeling that a return to treatment would not be too bad. These arguments are entirely speculative but deserve empirical study.

In a related point, current users might try very hard to quit on their own outside of any treatment facility (for their own reasons or to protect their families). If a public subsidy for treatment programs is available, they will reduce their outside effort and enter a program. Although they may work very hard for a cure within the formal treatment program, some of this effort is a substitute for outside effort, rather than a supplement. Thus, the net benefits of subsidized treatment would be reduced but not eliminated.

MARKET EQUILIBRIUM

The last step in cost-benefit analysis is to formulate the links among various policy options and utilization of treatment services. We would like to know the extent to which various policy options increase utilization of treatment facilities; the effect of policies on the prices paid for treatment by patients, employers, and insurers; and the cost of various programs to the public. All of these questions can be answered using the economists' tools of equilibrium analysis.

The Basic Model

Traditionally in economics, competitive equilibrium is defined by the intersection of supply and demand curves. The supply curve indicates the quantity offered for sale at each possible price, and the demand curve indicates desired purchases at each price. For prices above equilibrium, the resulting surplus (excess of quantity offered over quantity desired) places downward pressure on the price, whereas for prices below equilibrium, the resulting shortage places upward pressure on the price. At the price where the two curves cross, everyone desiring a purchase and everyone desiring to sell can accommodate that desire, and there is no further tendency for the price to move.

The market for drug treatment is much more complicated for three reasons. First, there are at least three interrelated markets to be analyzed: the market for drugs, the market for insurance, and the market for treatment. Second, quite a few parties desire the purchase, and each may face a different effective price (expenditure per unit of treatment) for the same physical purchase. For example, drug treatment may be partly voluntary and partly coerced, as addicts supplement court-ordered treatment. The addict would then pay one price while the insurance company pays another, with the two depending on the price charged by the treatment center and the details of the insurance contract (such as the copayment rate). The court ordering treatment would face a price of zero. Alternatively, an indigent uninsured addict may face a price of zero (or a low, subsidized price) while the public sector pays most or all of the price charged by the treatment center. Insurance contracts also involve several parties, as employer-provided health insurance is supplemented by personal purchases and partly subsidized by the state through the tax system. Third, in some cases the price charged depends on the quantity purchased, complicating both estimation and policy simulation.

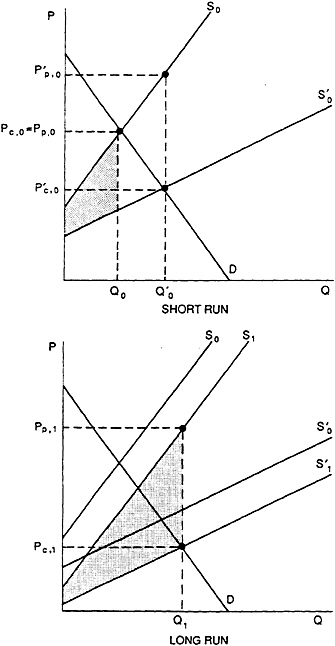

These complications will be illustrated progressively. Let us consider first an entirely free market for drug treatment. Drug treatment is supplied by perfectly competitive firms who can enter or leave the market costlessly in the long run, although the number and size of firms is fixed in the short run. There are no government subsidies for treatment, and there is no insurance coverage. Then, equilibrium is characterized in the standard way, as illustrated in Figure 1. With the initial demand curve D0 and short-run supply curve S0, the equilibrium price is P0 and quantity is Q0. If demand increases to D1, the price initially rises to P1, but this leads to excess profits at each treatment center, inducing entry of new firms which pushes the market supply curve to the right. The entry of new firms drives the price down, reducing excess profits per firm. The process continues until excess profits are zero, illustrated by the intersection of

Figure 1 Equilibrium in a free market without quantity insurance.

demand curve D1 and short-run supply curve S1. Assuming, quite reasonably, that this is a constant-cost industry, the long-run supply curve (which connects long-run equilibria for different demand curves) is the horizontal line L.

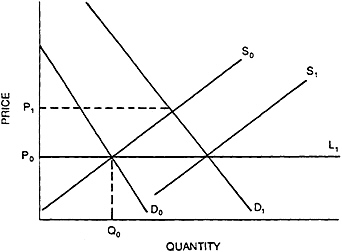

Court-Ordered Treatment and Demand

Court-ordered treatment affects the shape and location of the demand curve. To see this, we must first analyze the demand by individual addicts. Some would not voluntarily demand treatment at any price or would demand no more treatment than that provided for in the court order. In this case, the court is the only relevant source of demand. It is reasonable to assume that the court is relatively insensitive to the price paid by the addict, so we can approximate court-ordered demand by a vertical line, as illustrated in the first panel of Figure 2. Some addicts would voluntarily demand more care than the court orders but only if the price were low enough. For these addicts, the relevant demand curve is the dashed line illustrated in the second panel. Finally, some addicts desire more care than the court would order (presumably, court orders would not be necessary for these people) at any reasonable price. This case is illustrated by the final panel.

The market demand curve is the horizontal sum of individual demand curves, assuming that all demanders face the same price at any time. 25 In

Figure 2 Individual demand with court orders.

Figure 3, D1 through D3 denote the individual demand curves for three different people. Assuming that they are the only consumers in this market, the market demand curve is the illustrated dashed line. If there were many more consumers and the height of the kink points on individual demand curves was uniformly distributed, then the kinks would become much less noticeable in the market demand curve. In the limit, market demand would be smooth and downward-sloping despite the kinks in individual demand.

Figure 3 Deriving market demand.

Insurance, Tax Breaks, and Other Price Subsidies

For a typical insured patient, the addict pays full price up to the deductible and then pays a fraction of full price (proportional to the copayment rate) for further increments in service until coverage is exhausted (ceilings). Past this point, the addict again pays full price. If total medical care expenditures by the patient exceed a threshold and the patient itemizes expenditures on his tax return, there is an additional tax impact on price that depends on the patient's marginal tax rate.

Let us consider first a particularly simple insurance contract: the contract covers drug treatment from any provider, has no deductibles or caps, and has a copayment rate of C. Immediately, we are faced by the complication of three distinct prices: the price paid by the addict (denoted PC for consumer price), the price paid by the insurer (denoted P1, for insurer price), and the price received by the treatment center (denoted PP, for producer price). Unfortunately, a two-dimensional graph with quantity on one axis has room for only one of the three price variables. Luckily, the three are related to each other by the following formulae:

PC = C × PP and PI = (1 -C) × PP.

Thus, given C,26 we can graph either of the other two prices, find the equilibrium for that price, and calculate the equilibrium for the other price by applying the formula to the first equilibrium price.

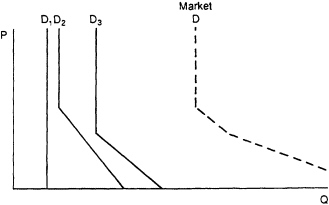

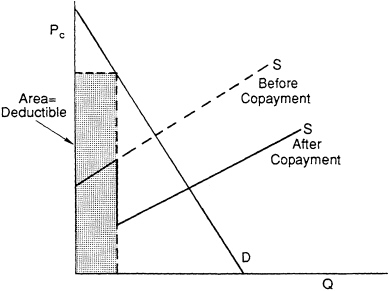

With no loss of generality, we will analyze the impact of insurance graphically using the consumer price. Copayment does not affect the de-

sire of the consumer to purchase at each given consumer price (although it clearly affects the price the consumer will be given); thus, the demand curve is unchanged by this insurance policy. Likewise, the producer's willingness to sell at each producer price is not affected by copayment. However, we cannot directly graph the supply curve (which depends on the producer price) on a graph whose vertical axis is the consumer price. Using the formula above, we can indirectly graph the supply curve, translating each producer price into its consumer price equivalent. This has the effect of lowering the intercept and rotating the short-run supply curve (as illustrated in the first panel of Figure 4) to S0.27 The new equilibrium producer price can be read off as the height of the initial supply curve S0 above the new equilibrium. This is clearly higher than the pre-insurance equilibrium producer price, so each treatment center would experience entry. This entry of new firms pushes the short-run supply curve to the right until it reaches S1 (illustrated in the second panel), at which point the new producer price is returned to its pre-insurance level.

Analytically, there is no difference between the effect of an insurance contract with copayment and the effect of a price subsidy paid for by the state.28 Either would decrease the price paid by the addict, increase the quantity of care purchased, and, by raising short-run profits, lead to long-run entry of new treatment centers. It can be shown that the total cost to the state or insurance company of this price subsidy is given by the two shaded areas in Figure 4 for the short run and long run, respectively (abstracting from administrative costs).

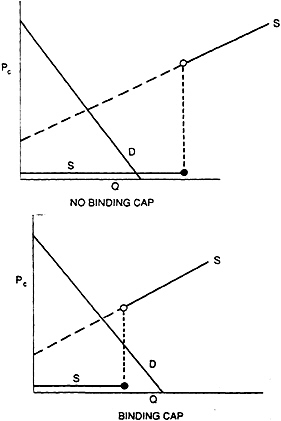

Some insurance policies do not require copayment, and sometimes the government subsidizes 100 percent of the cost (at least up to the quantity chosen by the addict). In these cases, it would appear to the addict as if the supply curve were horizontal at a price of zero, and equilibrium would be as illustrated in the first panel of Figure 5. Alternatively, there may be a binding cap on services paid for by either of these mechanisms, resulting in the situation portrayed in the second panel. In the first case, the subsidy has the effect of greatly increasing equilibrium purchases of care; in the second, the subsidy has no effect on equilibrium quantity,29 and merely transfers income from the state or the insurance company to the addict.

Now let us consider an insurance program with copayment and a deductible (that is, insurance payments are proportional to the excess of treatment charges over some threshold). To illustrate this, we must find a way to illustrate the point at which expenditures cross the threshold. To find this point, note that, at any point along the demand curve, a rectangle to the axes can be drawn. The area of this rectangle represents the consumer's total expenditures to that point because the height is price per unit, the length is the number of units, and area is height times length.

Figure 5 Effect of insurance without copayment or totally subsidized public care on equilibrium.

Thus, if we find the point on the demand line where the area under the rectangle exactly equals the deductible, we have found the point where insurance "kicks in." To the right of this point, copayment acts as a price subsidy as before. Equilibrium is illustrated in Figure 6.

Addicts who file federal income tax returns can receive a deduction for itemized medical expenditures in excess of a specified percentage of their adjusted gross income. The deduction amounts to a price subsidy, creating a wedge between net out-of-pocket, per-unit expenditures by the addict (the consumer price) and per-unit receipts of the treatment center (the producer price). The relation between the two is

PC = (1 -m) PP

Figure 6 Effect of copayment with deductibles.

where m is the addict's marginal tax rate. Thus, the effect of current tax treatment of medical expenses is analytically equivalent to the effect of an insurance policy with copayment and deductibles, and Figure 6 performs double duty.

Intertemporal Effects

The demand for future treatment depends on the current supply of addicts, which, in turn, depends on current governmental policies in several ways. First, there could be cycling as a result of price effects. Any massive, successful treatment effort that reduced the supply of current addicts would lead to a fall in the price of drugs. Lower prices would allow more teenagers to experiment with drugs and to purchase a greater quantity of drugs for these experiments. In turn, this experimentation increases the likelihood that they will become addicts in the future. It is important to note that the effect is not so large as to negate massive, successful treatment efforts. This is just one side effect whose size should be estimated and whose impact should be considered. Furthermore, the size of this effect is partly under the control of government. If the treatment program were accompanied by a government policy that reduced

the supply of drugs, then the tendency for the price of drugs to fall would be reduced or reversed.

Second, there could be risk compensation effects. Simply put, public actions that make products safer may induce consumers to take less care to protect themselves, so that the net increase in safety is smaller than projected. Applied here, potential drug users would be more likely to experiment with drugs if they felt that there was a cheap and painless antidote for addiction.

If the consequences of drug addiction to the user were drastically reduced through public action, substantial risk-compensation effects are likely. It is true that currently available public policies are unlikely to reduce the perceived personal harm of addiction by very much. Even if treatment were free, it would still be painful and time-consuming and would often fail. Furthermore, even if an individual's addiction were broken, the consequences of past addiction would largely remain. However, if the capability to implement a program that would drastically reduce the perceived consequences of drug use were ever to be developed, current nonusers might take less care to avoid addiction and would experiment with addicting drugs.

For most public programs, risk-compensation effects reduce the net gains of the program but never turn an effective program into a counterproductive one.30 In the case of drugs, the logical possibility of counterproductive effect is substantial, for drug addiction-causes external harms. Again, this is largely a theoretical possibility, given the current technology for drug treatment, but it might become a substantive consideration at some future point.

The Market for Insurance Policies

In the section above on insurance, tax breaks, and other price subsidies, the discussion showed how equilibrium in the drug treatment market depends on the quantity and type of insurance policy possessed by the addict. In turn, the equilibrium quantity and type of insurance depends on the appropriate supply and demand curves for insurance.

The demand for insurance policies is a derived demand, based on the increases in expected utility stemming from reduced financial uncertainty and (for those who know in advance they will need treatment) from expected income transfers. Anything that affects the expected future treatment market affects current insurance demand. For example, a reduction in the expected cost of treatment for the uninsured would reduce current demand for insurance.

There will be no attempt here to summarize the voluminous literature

on estimating the demand for insurance coverage;31 it will suffice to point out that all of the complications applicable to estimating the demand for treatment (discussed in the next section) also apply to the demand for insurance. Indeed, in the case of insurance demand, the problems may be even greater. Insurance is often purchased by the employer, presumably with the average employee in mind. Although the employer sets the general parameters, employees may be presented with several options for coverage and can always supplement employer coverage with private coverage.

The purchaser does not simply select a policy from a nonlinear budget set (as in the demand for treatment) but must select from discrete, nonlinear alternative formats (for exclusions, deductions, copayments, etc.) jointly with a level of coverage. The set of formats offered might change when government policies alter the demand for insurance on a large scale, so we have the complication of estimating a mutatis mutandis demand curve (that is, the demand curve allowing that which will change to change) rather than the ceteris paribus demand curve (holding all else constant).

For pure insurance (as opposed to insurance policies), the effective price is the difference between the yearly premiums and the expected annual payouts to the policyholder. In the insurance literature, this price is referred to as the ''loading factor.'' It is quite difficult to obtain accurate data on this variable, and one would probably have to settle for a rough proxy for the loading factor, perhaps adjusted for tax considerations. Even so, the complexities of the insurance market may cause the equilibrium price schedule (within a format) to be nonlinear. Finally, demand for insurance depends on employment status, as most health care insurance is purchased by employers. Consequently, one would need to take account of the addict's lower probability of employment.

Employers are the major demanders of health insurance, and the considerations previously mentioned apply here. The federal tax code provides major incentives that increase employer demand for health insurance. Employer-provided health insurance is not regarded as taxable personal income, but there is no deduction from taxable income for the individual purchase of health insurance. This distorts choices, encouraging substitution of employer for employee-purchased health insurance and, to a lesser extent, an increase in total demand for insurance. The previous discussion of the reasons why insurance has value to employers applies here, for this value determines desired purchases.

Many of the same complications that apply to insurance supply estimation apply to insurance demand estimation—it is difficult to measure price, and insurers select a format as well as a quantity to offer for sale at each price. Four sectors provide insurance: the government (through

Medicare and Medicaid and self-insurance of some government employees), for-profit commercial insurers (including mutual insurance companies), nonprofit insurers (chiefly Blue Cross and Blue Shield), and employer self-insurance. The aggregate supply is not simply the horizontal sum of supply curves of each sector because the different types of insurance are not perfect substitutes for each other. Additionally, some suppliers restrict sales to certain categories of consumers.

Estimation and Simulation Issues

Although the theory of equilibrium enables one to predict the direction of change caused by public policies, one cannot predict the size of the changes in treatment utilization, price, or cost to the government without empirical estimates of the locations and shapes of the relevant supply and demand curves. In particular, many policies have the effect of reducing the price paid by consumers of treatment. To determine whether this reduction is worth the cost, it is critical to estimate the slope of the demand curve, which reveals the sensitivity of utilization to price.

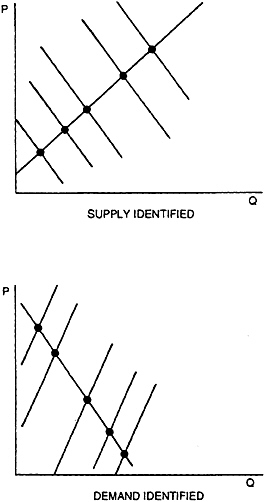

For traded goods, economists typically employ observations on prices and quantities exchanged to estimate demand and supply curves. After using statistical techniques to hold constant all those factors affecting the location of the demand curve, the different equilibria observed (which are caused by differing locations of the supply curve) trace out, or "identify" demand. Similarly, by statistically removing the impact of variables that move the supply curve but allowing demand to vary, one can identify the supply curve. These procedures are illustrated in Figure 7.

This procedure breaks down whenever the observed prices and quantities do not represent the intersections of supply and demand curves. In some cases, there is excess demand for services and yet the price is not allowed to rise (for example, because the service is provided by a public clinic with distributional rather than profit-maximizing interests). In this case, the observed price and quantity point lies on the supply curve but not on demand, and the demand curve cannot be estimated. Techniques applicable for nontraded goods may be applicable here. In any case, this problem is only likely to infect the low end of the demand curve. It would still be possible to estimate the high end of the demand curve from observations generated by private clinics without waiting lists. As a rough approximation for the inestimable low end, one might simply continue the high-end demand curve downward in a smooth and plausible way.

It is not enough to estimate aggregate demand for treatment, for not all treatments are alike. Ideally, we would like to estimate treatment demand separately for public, for-profit, and nonprofit facilities and for

Figure 7 Identifying supply and demand from observations of price and quantity.

each modality of treatment. In particular, we would like to estimate cross-price elasticities, which would indicate the effect on the demand curve for, let us say, for-profit hospital 28-day treatment of a decrease in the price charged by 6-month nonprofit facilities. We would also like to understand crowd-out effects between the public and private sectors. If government clinics increase their service provision, does total service provision rise, or does the government merely take over treatment for formerly paying customers? Finally, relapsers are likely to have a different responsiveness to

price than first timers and should probably be sorted out. To some extent, relapsers are locked in to their original treatment facility because of the mutual gains in information from the first treatment. We might also wish to study separately relapsers who return to their original facility and those who go elsewhere.

Once again, the quality of service complicates estimation. The average quality of service is determined endogenously in a market setting. Any public policy that changed the location of the aggregate demand curve could affect the equilibrium level of quality, feeding back on demand. In effect, we would have two demand curves: the ceteris paribus curve, estimated from a cross-section and holding quality constant, and the mutatis mutandis curve, estimable from time series and allowing quality to vary endogenously. Although the mutatis mutandis demand curve would be harder to estimate, it is the one that is relevant for simulating the effects of policy changes on service utilization.33

Nonlinear prices complicate both estimation and policy simulation. Such prices occur when the price paid or received per unit is a function of the number of units purchased, so that total expenditures or receipts are not simply proportional to the quantity exchanged. Demanders face nonlinear prices when they are offered quantity discounts or guarantees. For example, one treatment center offered free treatment for relapsers, although this policy was subsequently discontinued. 34 Suppliers face nonlinear prices when a client declares bankruptcy after paying for part of the services he received, or when a client reaches his insurance ceiling and the treatment facility continues treatment anyway on a charity basis.

As long as prices follow an externally fixed schedule, supply and demand curves are well defined. It makes sense to ask the question "What quantity would the addict wish to buy at each possible price?" even though the quantity decision determines the price, for suppliers could fix the price schedule in alternative ways and the form taken by this schedule is external to the demander. However, the simultaneity of the price and quantity decisions enormously complicates the estimation problem.

Health econometricians have recently developed statistical techniques to cope, in part, with the nonlinearity of prices,35 and have utilized experimental data from the RAND Health Insurance Experiment to deal with simultaneity and other problems.36 They have not yet incorporated Hausman's econometric technique for nonlinear budget constraints, 37 but it is quite possible that great progress could be made if further thought were devoted to adapting this technique to health care demand.

Nonlinearities also complicate policy simulation. Price and income elasticities cannot be used in any simple way to estimate the impact of public policy changes, for inframarginal prices have distinct "virtual income" effects and nonconvexities lead to discontinuities. An appropriate metho-

dology for performing policy simulations in this setting, developed by Feldstein and Lindsey,38 could be applied fruitfully to medical demand as well.

SOME POLICY IMPLICATIONS

A free market in drug treatment is likely to be suboptimal because drug treatment produces external benefits not entirely captured by the addict, his family, his employer, or his insurer. Some governmental intervention is warranted, although the optimal amount of intervention cannot be determined without a great deal more study. Increases in intervention beyond the current level can be justified if (a) they reduce the scope of the drug problem or (b) they reduce the financial consequences of nonpaying customers of treatment facilities or paying customers who thereby leave their families destitute.

If we are persuaded that current subsidy levels are inadequate, a number of policy choices remain. The government can stimulate increased use of treatment facilities by subsidizing the addict, his employer, insurance firms, or treatment facilities. Subsidies can be direct or in the form of a tax break. Finally, service can be mandated without subsidy. Three categories of policies are briefly considered here: policies to increase the supply of service, policies to increase the efficiency of service, and policies to intervene in the health insurance market.

The Supply of Treatment

Treatment is supplied by government, nonprofit, and for-profit organizations. Although there may be no shortage of the higher priced for-profit hospital-based treatment alternatives, there appears to be a substantial undersupply at the lower end of the market. Press reports indicate that thousands of addicts must wait months to obtain treatment39 and that treatment centers in Dade County, Miami, New York, Los Angeles, Texas, and Arizona have substantial waiting lists.40 In New York, "addicts who seek treatment are routinely told to come back in weeks, even months. Most addicts don't wait passively."41 Whereas some of those put on waiting lists or refused treatment may find treatment elsewhere, Barbara Butler, director of the James Center in Watts, estimated that "80% of those refused admission resume their drug habits."42 It is not clear how typical Ms. Butler's observation is, but surely the impulse to seek treatment for addiction is an intermittent one.

Part of the problem is due to federal cutbacks. Prior to the 1980s,

most drug treatment services were provided at little or no cost by public agencies or through public contracts with private nonprofit agencies.43 Although these sources are still important, client fees, insurance payments, and third-party public payments through Medicaid have increased rapidly since then.44 In part, the increase in insurance coverage is a direct result of government cutbacks—there was not much point in insuring to cover a free treatment. Federal block grants for treatment and prevention were cut by about 25 percent in 1981-1982, and it was not until passage of the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act that the real value of federal block grants returned to its 1981 level. 45

In general, we would expect a portion of federal cutbacks to be made up by increases at the state and local level and by increases in donations to nonprofit drug treatment centers. Recent unpublished data compiled as the 1987 National Drug and Alcoholism Treatment Utilization Survey (NDATUS) confirm that state spending has, indeed, risen substantially, while donations have remained essentially flat. This growth in spending may reflect increasing perceived need as well as revenue substitution, so that federal cutbacks may have had a substantial impact on total expenditures. Although no careful econometric study has specifically addressed drug treatment block grants, the evidence from broader federal expenditure programs suggests that increasing need is the pre-dominant factor. Most studies find that, after controlling for perceived need, state reactions amplify federal cutbacks (the so-called flypaper effect), and federal cutbacks cause only small increases in donations.46

Private for-profit treatment centers provide another alternative following federal cutbacks. The 1987 NDATUS indicates substantial growth in this component of the treatment sector, especially over the past five years. It seems clear that private for-profit treatment centers will arise automatically whenever clients are willing to pay for services. Entry of nonprofit alternatives is much more restrained, as nonprofit organizations do not appear to respond as rapidly to emerging market opportunities. A study by Henry Hansmann of four mixed for-profit/nonprofit industries found that the nonprofit share fell when demand grew rapidly.47 Thus, excess demand is concentrated on the low end.

Federal policies to address the shortage can either concentrate on subsidizing the indigent so that they can afford for-profit care or subsidizing low-cost state and nonprofit clinics to allow them to expand their charity care. Financial subsidies to treatment centers can take the form of direct grants (as in the Hill-Burton hospital construction program) or tax breaks and can be made contingent on charity care or anything else the government wants. Tax breaks for treatment centers could take the form of an accelerated depreciation allowance for investment in new facilities. Because for-profit treatment centers appear to enter the market

at a sufficiently rapid pace even without these subsidies, extending further subsidies would simply transfer income from taxpayers into the hands of for-profit investors. Nonprofit centers are already tax-exempt, so further subsidy would have to come in the form of grants. One reason nonprofit facilities are slow to respond to increased demand is the difficulty of securing capital, as the nondistribution constraint effectively eliminates equity financing options. Exemption from the corporate income tax serves as a crude corrective for difficulty in expanding48 but cannot help in providing the capital for starting a new organization. Furthermore, federal drug financing policy has explicitly precluded using block grants for capital, land, bricks, or mortar. Thus, consideration of capital subsidies, restricted to nonprofit treatment centers, is warranted.

Another problem of supply stems from community opposition to new treatment centers.49 Siting an "obnoxious" facility (such as a public housing project, toxic waste dump, or prison) is not an easy task for any level of government,50 and local opposition can tie up a treatment center for years.51 Thus, it would be quite useful to study the extension of eminent domain to private treatment facilities serving the public interest. Eminent domain still requires approval by elected representatives; consequently, this policy would not be sufficient to eliminate slow construction owing to local opposition. The problem is more severe for new freestanding clinics than for new hospital-based programs at existing hospitals. This difficulty with expansion should be kept in mind when comparing the cost-effectiveness of the two alternatives.

Policies to Encourage Efficiency

There is a long-standing debate on the merits of direct government provision of services versus government contracts with the private sector (including both for-and nonprofit facilities). In the drug treatment field, the debate is more theoretical than practical, as the vast majority of publicly subsidized treatment is provided through contracts and grants with the private sector. Presumably, contracting for services enhances efficiency, and, indeed, it can serve that purpose. However, there is good reason to believe that the current practices of government do not maximize the efficiency advantage over in-house production. Indeed, as practiced, the advantage may be minuscule.

Paulson nicely summarized the issues as they apply to human services.52 The four most commonly cited advantages to contracting are lower cost and greater efficiency, increased flexibility, greater competition with enhanced consumer choice, and a better-quality, more effective service. He finds little evidence supporting these claims for the broadly

defined human service industry.

Part of the problem is due to a failure to employ competitive bidding practices. What Paulson calls "the most complete study of contracting for human services to date" (p. 93) found that minimal competitive bidding has occurred. When bidding did occur, inexperienced social service agencies made unrealistically low bids that led to cuts in service or a lowering of quality, or both. Paulson concluded that the failure to employ competitive bidding procedures may be inherent in political systems.53

If political systems are inherently unable to employ competitive bidding procedures consistently, contracting will not result in more efficient production. A better approach might be to give each addict a voucher that would allow purchase of a specified dollar amount of services at any (certified) treatment center chosen by the addict. The voucher system extends the benefits of competition, already available for the high end of the market, to the low end. Treatment facilities that did not provide full value for the money would lose customers, and this prospect provides them with an incentive to improve. Facilities would further compete by experimenting with new treatment techniques and technologies, and society would benefit if any of these techniques proved successful. In equilibrium, a diversity of treatment technologies would reflect the diversity of treatment needs of different kinds of patients, an outcome far from guaranteed when service is provided or contracted for by a centralized government bureaucracy.

To be effective, vouchers would have to be restricted to certified treatment centers. The reason is simple: many addicts are not really interested in being cured. Addicts might prefer "treatment" at countryclub type facilities that would be pleasant to visit, although not very therapeutic. A facility that told its patients that "addiction is society's fault and you are merely a victim" might out compete a facility that told its patients that "only the addict can cure himself, and only through hard work and self-examination." Recalling that the chief reason for subsidizing drug treatment is to reduce externalities stemming from the choices made by drug addicts, it seems somehow inappropriate to tout the virtues of providing the addict with a greater choice of treatment options.

Certification would restrict the addict's choices, reducing the benefits accruing from competition. This problem would be especially acute in small communities where only one or two facilities would be certified. However, as long as there is more than one truly competing facility, 54 each facility would have a profit incentive to improve its value-for-money.

Effective certification would be quite difficult, however. Although it may be easy for the government to detect and restrict a facility's overinvestment in country-club atmosphere, some of the other less desirable forms of competition would be harder to regulate. The treatment firm

would have a profit incentive to get around any regulations designed to control opportunistic behavior, and it would be hard to write a comprehensive set of standards to control the sort of appeals suggested above. Detecting violations of such complex standards would also be difficult, and one should expect prolonged, expensive legal challenges by decertified facilities. Even if we trusted addicts to try to choose treatments that were most beneficial to society at large, it is not clear that they have the capacity to do so. Paulson noted the general inapplicability of "greater consumer choice" for services in circumstances in which it is quite difficult for consumers to evaluate differences in quality. He also argued that consumers of human services have the least capacity to make such evaluations.

In sum, either competitive bidding in contracted-for services or provision of vouchers has the potential to lower costs and increase effectiveness of treatment. However, practical and political considerations may keep these policies from achieving that potential.

Insurance Options

One serious proposal is to subsidize the purchase of health insurance generally or for drug addiction specifically. However, health insurance is already heavily subsidized. As noted earlier, exemption of employer-provided health insurance from the federal personal income tax acts as a substantial subsidy. Most analysts feel that the level of subsidization is already excessive, contributing to the crisis in health care costs, so that further increases would be undesirable. Pauly concluded: "The nature and importance of the distortion from the tax subsidy to health insurance is generally agreed upon, although its magnitude is still open to considerable question."55 Furthermore, the current system of tax subsidization favors those with higher income, and an alternative tax credit system has been proposed.56

Pauly points out one qualification to his conclusion: subsidization would not be excessive if there were sufficient external benefits to health insurance. In general, he concludes that external benefits are not sufficient, but he did not specifically address drug treatment. To the extent it is effective, drug treatment has substantial external benefits, so that an added subsidy targeted toward this goal might well be warranted. In addition, the current subsidy structure, by its very nature, will subsidize the wrong people. Many addicts are unemployed or face low marginal tax rates, hence receiving a smaller subsidy than nonaddicts.

The problem with simply subsidizing employer provision of drug treatment insurance is that such subsidies could not reach the unemployed or