4

The Immersion Study

OVERVIEW

Comparing the Effects of Three Approaches to Bilingual Education

A treatment is an intervention or program that may be applied to or withheld from any individual in a population. In the simplest of settings, a treatment is a discrete event, performed briefly in the same way for all individuals; for instance, the injection of the Salk polio vaccine is a treatment in this sense. Quite often, however, a treatment is more complex, extending over a period of years, with many individuals involved in its delivery. This is particularly common in the field of education, though it is also common in caring for the chronically ill and in preventive medicine. Studies of such complex treatments inevitably and unavoidably encounter various difficulties concerning the definition, nature, and stability of the treatments. This section discusses these issues as they arose in the Immersion Study and considers how they were addressed.

The Immersion Study was conceived as a comparison of three treatments, called Immersion, Early-exit, and Late-exit. The final report of the Immersion Study was published in two volumes (Ramirez et al., 1991a, 1991b; hereafter called the Immersion Report) states (1991a, page 32): “The primary objective of this study is to assess the relative effectiveness of structured English immersion strategy, early-exit, and late-exit transitional bilingual education programs.” All three programs were intended for students who speak Spanish, but have limited ability to speak English. All three programs had, as one of their goals, teaching students English. The conceptual distinction between the treatments is described in the Immersion Report (1991a, Table 4), to which the reader should refer for

a more detailed discussion. In abbreviated form, the distinction is essentially as follows:

-

Immersion: All instruction is in English, though the teacher is bilingual and may use Spanish in informal conversations and when clarifying directions. Students leave the program as soon as they have demonstrated proficiency in English, typically after 2–3 years.

-

Early-exit: The teacher uses both Spanish and English in instruction, though content areas are taught in English. There may be instruction in Spanish-language skills, but the emphasis is on developing English-language skills. Students leave the program as soon as they have demonstrated proficiency in English, typically after 2–3 years.

-

Late-exit: Students are taught both Spanish and English language skills, and both languages are used for instruction. All students leave the program at the end of the fifth or sixth grade.

As a basis for comparing and contrasting the panel's analysis of the Immersion Study, we present first the summary prepared by the U.S. Department of Education (U.S. Department of Education, 1991).

The Longitudinal Study of Structured English Immersion Strategy, Early-Exit and Late-Exit Transitional Bilingual Education Programs

This study compared the relative effectiveness of two alternative programs (structured English immersion and late-exit transitional bilingual education) with that of early-exit transitional bilingual education programs. The intent of the report is to describe characteristics of the instructional treatments and to identify similarities and differences among the three instructional approaches. Identifying such differences and similarities will help determine how changes in student achievement can be attributed to various instructional techniques.

According to the study's final report (Ramirez et al., 1991a, 1991b):

-

The three programs represent three distinct instructional models. The participating teachers demonstrated and sustained language-use patterns that were faithful to the respective models, and the differences in student performance were overall attributable to differences in those approaches rather than to student, or other critical characteristics.

-

Notwithstanding the programmatic differences, there were important and surprising similarities. Classroom activities tended to be teacher-directed, with limited student opportunities to produce language. Students produced language only when directly working with a teacher and then only in response to teacher initiations. Across all programs, teacher questions were typically low-level requests for simple information recall. The strategies used made for a passive learning environment which placed limits on students' opportunities to produce language and develop more complex language and conceptual skills.

-

On the average, teachers in all three programs had sufficiently high oral English language skills to teach effectively in English, but only the Late-exit program had teachers with Spanish oral language skills that were sufficiently high to effectively teach in Spanish.

-

Regarding relative impact, after four years in their respective programs,

-

limited English-proficient students in immersion strategy and early-exit programs demonstrated comparable skills in mathematics, language and reading when tested in English. There were differences among the three late-exit sites in achievement level in the same subjects: students in the site with the most use of Spanish and the site with the most use of English ended Grade six with the same skills in English language and reading; students in the two late-exit sites that used the most Spanish posted higher growth in mathematics skills than the site which abruptly transitioned into almost all English instruction. Students in all three programs realized a growth in English language and reading skills that was as fast or faster than the norming population.

-

Parental involvement, particularly in length of time spent helping students with homework, appears to be greatest in the Late-exit programs. This suggests that schools should explore how they might use the home language of their students to engage parents in the schooling of their children.

Treatments and Treatment Effects

The effect of a treatment on one student is defined in terms of the responses that the student would exhibit under alternative treatments. Each student has a potential response that would be observed under each treatment. For instance, if the outcome is a score on a test of reading in English, each student has three potential scores: a score, yI, that this student would produce if the student were placed in an immersion program; a score, yE, that this student would produce if placed in an early-exit program; and a score, yL, that this student would produce if placed in a late-exit program. If yL > yE, then this particular student would achieve a higher reading score if placed in a late-exit program than if placed in an early-exit program, and the difference, yL-yE, is the effect on this one student of applying the late-exit program rather than the early-exit program.

If z stands for the program a student actually receives, then z = I if the student is placed in an immersion program, z = E for an early-exit program, and z = L for a late-exit program. Each student has a value of z. Each student is of course placed in only one program. Thus, for each student, yI is observed only if the student is placed in an immersion program, that is, only if z = I; yE is observed only in an early-exit program, that is, only if z = E; and yL is observed only in a late-exit program, that is, only if z = L. As a result, the effect of a program on an individual student, say yL-yE, may never be calculated. Rather, treatment effects must be estimated for groups of students by comparing those who received different treatments (see “Data Analysis and Interpretation,” below).

The Immersion Study did not create programs with prescribed characteristics, but rather searched the country to find programs that fit one of the three categories, Immersion, Early-exit, or Late-exit. The search and classification are described in Chapter 2 of Volume I of the Immersion Report. Immersion and Late-exit Programs are comparatively rare and were the basis for the search.

Table 4-1 shows the structure of the Immersion Study. Note that Late-exit

TABLE 4-1 Structure of the Immersion Study

|

Site |

State |

Immersion |

Early-exit |

Late-exit |

|

A |

TX |

X |

X |

|

|

B |

CA |

X |

X |

|

|

C |

CA |

X |

X |

|

|

D |

FL |

|

|

X |

|

E |

NY |

|

|

X |

|

F |

TX |

X |

X |

|

|

G |

NY |

|

|

X |

|

H |

NJ |

X |

|

|

|

I |

TX |

|

X |

|

|

SOURCE: Ramirez et al. (1991a, Table 5, page 39) |

||||

Programs do not appear in the same school district as other programs, while Immersion and Early-exit Programs do appear in the same district, and sometimes in the same school. The report states (Ramirez et al., 1991a, page 39): “The late-exit transitional bilingual program represented a district-wide policy”

A treatment, program, or intervention typically has many aspects—some of which are explicitly intended while others occur unintentionally. A student who receives the treatment is exposed to all of its aspects. At times, one may be able to say with confidence that a treatment has had a particular effect and yet be unable to say which aspect of the treatment produced the effect.

Since the programs in the Immersion Study were found and not created to specifications, the programs have aspects that were not part of the definitions of the treatments given earlier. For instance, the Immersion Report notes that more teachers in Late-exit Programs were Hispanic or knew more Spanish than in other programs. Also, teachers in the Late-exit programs were “better educated and have more specialized training to work with language minority children than teachers in immersion strategy or early-exit programs” (Ramirez et al., 1991a, page 186). Specifically, substantially more teachers in the Late-exit Programs had master's degrees. These features of the Late-exit Program are not part of its intended definition, but they are aspects of the program and thus of the treatments actually received by the students.

The Immersion Report does quite a good job of documenting unintended aspects of the programs. Even with this good effort, however, it is possible and perhaps likely, that the programs differ in still other unintended ways that were not observed. These, too, are inextricable parts of the treatments.

To the extent that the immersion Study is a horse race between existing programs as they are currently implemented, the issue of unintended features of the programs is not a major problem. It becomes a significant problem if one wants to go beyond declaring a winner or declaring a tie to attributing the victory

or tie to the intended features of the program and not to the unintended features. A horse race may have a clear winner while providing limited information about what made that horse win. The panels notes, however, that the horse race aspect of the Immersion Study is neither uninteresting nor irrelevant for policy. A clear winner might tell policy makers that they want more programs “like that,” while leaving us in doubt about the essential features of a program “like that” but eager to try to duplicate all of the features.

In a study with many more sites than the Immersion Study, or with fewer unintended aspects of programs, it might be possible to use analytical procedures to formulate an educated guess about which aspects of programs contributed to their performance; at least, this might be possible for the aspects that were measured and recorded. In the Immersion Study, however, it is not clear, and perhaps not likely, that such analyses would yield much.

In addition to unintended aspects of the three different programs, there are also unintended differences in implementation of the “same” program at different sites. Again, the Immersion Report does an admirable job of describing some of these differences. For instance, the report states (Ramirez et al., 1991a): “… only teachers in the immersion strategy program sites are homogeneous in their [near exclusive] use of English.” Other strategies varied considerably in their use of English: for example, “Early-exit site F classrooms are practically indistinguishable from immersion strategy classrooms in that teachers at this site also use English almost exclusively …” Other variations are also described.

Although the Immersion Study was just described as a horse race between existing programs having both intended and unintended aspects, it is more accurate to describe parts of the Immersion Study as several separate horse races between related but not identical treatments.

Who Was Measured? What Was Measured? When Was It Measured?

In an ideal educational experiment or observational study, well-defined groups of students receive each treatment, and outcomes are available for all students in each group. This ideal is often difficult to achieve when students are studied for a long time.

The Immersion Report discusses losses of students over time (Ramirez et al., 1991a, pages 369–376). Table 4-2 is adapted from that discussion. Some students left the study without being reclassified as fully English proficient (FEP), that is, they left the study in the “middle.” Almost all of the students who left early transferred to a class, school, or district that was not part of the Immersion Study or left for unknown reasons. In all three groups, more than one-half of the students left the study early. Ramirez et al. (1991b, page 20) says:

Attrition of the student from the study meant no additional test scores could be obtained for that student. The predominant reason for attrition was that the student's family moved outside the district. Students who were mainstreamed were not considered to have left the study: test scores for mainstreamed study students are not missing by design.

TABLE 4-2 Students Leaving the Studies

|

|

Program |

||

|

Students |

Immersion |

Early-exit |

Late-exit |

|

Total Number in Each Program |

749 |

939 |

664 |

|

Number Exiting the Study Without Being Reclassified as FEP |

423 |

486 |

414 |

|

Percent |

56% |

52% |

62% |

Despite this statement, more than 30 percent of the students who left early changed classes or schools without leaving the school district (Ramirez et al., 1991a, Table 168).

Losses of this kind are not uncommon in educational investigations. The losses here are less severe than those in the Longitudinal Study (see Chapter 3). Nonetheless, from the two volumes of the report, it is difficult to appraise the impact of the loss of so many students. If the students who left were similar to those who remained, then the impact might be small. If similar students left each program, but they differed from those who remained, this might alter the general level of results without favoring any program to the detriment of others. For instance, this situation might happen if students left programs only because their parents moved. It is also possible, however, that the students leaving one program differ from those leaving another; this might happen if some students or parents had strong feelings about the programs. An additional analysis of considerable interest might have been to compare the background or baseline characteristics of students in six groups categorized by leaving or staying in each of the three programs and attempting to adjust the results for any observed differences.

The application of a treatment occurs at a specific time. Measurements made prior to the start of treatment might not be affected by the treatment; in this report such quantities are labeled as covariates (this is a more restrictive use of the term than might be occur in other settings). Quantities measured after the start of treatment may be affected by the treatment; such quantities are labeled as outcomes. The formal distinction can be related to the discussion above: for each student, a covariate takes a single value, but an outcome has three potential values for each student, depending on the treatment received by the student.

When the distinction between outcomes and covariates is ignored, analytical procedures may introduce biases into comparisons where none existed previously. Specifically, if an outcome is treated as a covariate—that is, if adjustments are made for an outcome variable—it may distort the actual effects of a treatment, even in randomized experiments.

In the Immersion Study, adjustments for outcomes appear in three guises.

First, pretest scores for kindergarten students are not actually pretest scores; they were not obtained prior to the start of treatment, but, rather, in the early part of kindergarten. This first adjustment attempt would be fairly unimportant if programs were to take years to have material effects, a possibility that is reasonable but not certain. In the absence of genuine pretest scores, the researchers' decision to use early kindergarten scores instead of pretest scores was probably the best alternative.

In the second guise, the “number of days absent” is actually an outcome, perhaps an important one, that may have been affected by the treatments if students found one program particularly frustrating or satisfying. The Immersion Study uses this variable as a covariate (Ramirez et al., 1991b, page 81). If one of the program treatments had a dramatic effect on this variable, adjusting for it—that is, treating it as a covariate—might distort the treatment effect. The researchers should have conducted simple analyses to investigate the possible effects of the programs on the “number of days absent” and should have considered the possible impact of such effects on their adjustments. Simple methods exist to do this; one reference is Rosenbaum (1984, section 4.3).

The third guise in which adjustment for outcomes occurs is discussed in connection with the cohort structure of the study. The study had a fairly complex cohort structure (Ramirez et al., 1991a, page 41), with six different cohorts of students in the first year of data collection; see Table 4-3.

Specifically, a group or cohort of children was followed, beginning in kindergarten, for each of the three programs or treatments. For Immersion and Early-exit Programs, an additional cohort was followed, beginning in first grade. For Late-exit Programs, a cohort was followed, beginning in third grade.

As the authors noted (Ramirez et al., 1991a, page 32), “the primary objective of this study is to assess the relative effectiveness of structured English immersion strategy, early-exit, and late-exit transitional bilingual education programs.” The third-grade Late-exit cohort is of no use for this main objective, though it may have other appropriate uses.

The panel's impression from the Immersion Report is that students in both of the first-grade cohorts had also often been in Immersion or Early-exit Programs in kindergarten, and it is only the observation of these children that begins in first

TABLE 4-3 First Year Study Cohorts by Grade

|

|

Program |

||

|

Kindergarten |

Kindergarten |

1st |

3rd |

|

Immersion |

X |

X |

|

|

Early-exit |

X |

X |

|

|

Late-exit |

X |

|

X |

grade. The real problem is that we do not know which program they were in, which limits the usefulness of the first grade cohorts for the “primary objective.” First graders had been exposed to a treatment, and may have been affected by it, for more than a year before any measurements were recorded. As a result, all measurements on these students might, in principle, have been affected by the treatment. There are no covariates or baseline measurements. As a result, it is not possible to examine the comparability of the first-grade cohorts prior to treatment or to use covariates to adjust for baseline differences. It is like watching a baseball game beginning in the fifth inning: if you are not told the score from prior innings, nothing you see can tell you who is winning the game.

This concern about comparability occurs frequently in observational studies, in contrast to randomized experiments, because the treatment groups often differ systematically and substantially prior to treatment. The panel therefore concludes that the first-grade cohorts are of limited use for the “primary objective” of the Immersion Study.

DATA ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION

Comparability of Treatment Groups: Overt and Hidden Biases

In randomized experiments, the random assignment of students to treatment groups is intended to ensure that the students in different groups are comparable prior to the start of treatment. Somewhat more precisely, conventional statistical procedures applied to the results from experiments take into account the kinds of noncomparability that random assignment may create. In contrast, in observational studies the students in different treatment groups may not have been comparable prior to the start of treatment. Indeed, there is ample evidence of this in the Immersion Study. A major focus of the analytical effort in an observational study is distinguishing the actual effects of the treatments from the initial lack of comparability of the treatment groups. This section discusses the comparability of the groups in the Immersion Study, the adjustments made for noncomparability or bias, and the detection and assessment of hidden biases that were not adjusted for.

By long and established statistical tradition, noncomparability of treatment groups is referred to as “bias,” a somewhat unfortunate term. In nontechnical English, the word “bias” suggests deliberate malfeasance, but this meaning is not intended in the present context. Biases afflict most observational studies, and good researchers recognize their probably existence and attempt to adjust for them. The Immersion Study included such attempted adjustments.

An overt bias is one that is visible in the data at hand. A hidden bias is one that is not observed, measured, or recorded. Care is needed to avoid mistaking either overt or hidden biases for effects of the treatments. This section first presents examples of overt biases in the Immersion Study; it then discusses the adjustments for them and notes the lack of attention to sensitivity to hidden biases.

TABLE 4-4 Gross Family Income of Study Students

|

|

Program |

||

|

Family Income |

Immersion |

Early-exit |

Late-exit |

|

< $7,500 |

25.4% |

19.7% |

40.7% |

|

> $20,000 |

19.1% |

21.3% |

8.9% |

|

SOURCE: Ramirez et al. (1991a, Table 148, page 351) |

|||

The Immersion Study contains many overt biases. Four examples serve to illustrate the point. Tables 4-4 to 4–6 provide information about characteristics of the families in the different programs. The tables have an implicit row of “other” so that the columns add up to 100 percent. The first example concerns family income. Table 4-4 compares the three treatment groups in terms of gross family income. Although family income is not high in any group, children in Late-exit Programs tend to come from families with substantially lower incomes than children in other programs.

The second and third examples concern the proportion of parents receiving Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and the proportion of children attending preschool; see Table 4–5. Once again, the most dramatic differences are those between the Late-exit Programs and the other programs. Far more parents of students in Late-exit Programs receive AFDC; far fewer children in Late-exit Programs attended preschool.

The fourth example of an overt bias compares the treatment groups in terms of newspapers that the students' parents regularly receive. Here, the big difference is in the receipt of Spanish-language newspapers, which is far more common among the parents of students in Late-exit Programs; see Table 4–6.

In many instances, the Immersion and Early-exit groups appear more comparable to each other than either group is to the Late-exit group. It is likely that this is not an accident: Immersion and Early-exit Programs were typically selected from the same school district, and often from the same school, while Late-exit Programs typically came from other districts (see Table 4-1 above). This issue

TABLE 4–5 AFDC Receipt and Preschool Attendance

|

|

Program |

||

|

Characteristic |

Immersion |

Early-exit |

Late-exit |

|

AFDC |

16.8% |

12.7% |

47.2% |

|

Attended Preschool |

44.4% |

37.0% |

29.4% |

|

SOURCE: Ramirez et al. (1991a, Tables 149 and 150, pages 352 and 354) |

|||

TABLE 4–6 Parents Newspaper Receipt, by Language

|

|

Program |

||

|

Newspaper Language |

Immersion |

Early-exit |

Late-exit |

|

English |

42.8% |

48.0% |

42.9% |

|

Spanish |

28.0% |

27.7% |

54.1% |

|

SOURCE: Ramirez et al. (1991a, Table 152, page 356) |

|||

turns out to be important for the interpretation of the Immersion Study, because there appear to be substantial differences between schools and school districts, or perhaps differences between the communities served by different schools. This point is elaborated on in the next section. In short, there are many overt biases: the groups differ prior to treatment in many ways we can see, and these differences were not controlled for.

Adjusting for Overt Biases

As discussed above, the three treatment or program groups differed prior to the commencement of the treatment in various ways identifiable in the available data. The Immersion Report includes an attempt to handle these differences by using covariance adjustment, a standard statistical approach. These analyses divide into three groups, described in Chapters 3–5 of Volume II of the Immersion Report. The first group (in Chapter 3) makes comparisons of two different programs in the same school. The second group (in Chapter 4) makes comparisons of two programs in the same school district, but not necessarily in the same school. The third group (Chapter 5) makes comparisons that involve programs in different school districts. Unfortunately, as we have noted, Late-exit Programs always appear alone, in a district without other study programs. As a result, comparisons involving Late-exit Programs are always in the third group.

As the Immersion Report notes (Ramirez et al., 1991b, page 93):

When a single school has both programs, the [Immersion] and [Early-exit] programs can be compared without concern that differences between schools or districts are affecting results. In addition, controlling for school effectively controls for the attributes of the community served by the school.

Elsewhere, the report states (page 44):

The analyses that may be performed to evaluate the nominal program are severely limited by the study design, which in turn was severely limited by the paucity of [Immersion] and [Late-exit] programs. Despite an extensive national search, only a handful of immersion strategy and late-exit programs were identified. Essentially all of the districts with [Immersion] and [Late-exit] programs agreed to participate in the study. However, no district with a late-exit program had any other program. This fact, together with the limited

number of districts with late-exit programs, makes comparison of the [Late-exit] program with the [Immersion] and [Early-exit] programs extremely difficult. That is, one cannot control for district or school level differences.

The panel agrees with these observations and concurs with the authors of the report that the first group of analyses is the most credible for the reasons given. This is a key point in interpreting the results of the Immersion Study. In addition, the panel generally regards the analyses of kindergarten through first grade as more compelling than analyses of first through third grades.

The Most Compelling Comparisons: Programs in the Same School for Grades K-1

For the K-1 analyses in the same school that the panel finds most compelling, there were four major conclusions in the Immersion Report:

-

Although the immersion strategy students tend to score five or six points lower than early-exit students on the mathematics subtest, the difference is not statistically significant (page 103).

-

Although the immersion strategy students tend to score four to five points higher than early-exit students on the language subtest, the difference is not statistically significant (page 105).

-

The immersion strategy students tend to score eight to nine points lower than early-exit students on the reading subtest, and the difference is statistically significant at the .05 level (page 108).

-

The subsequent analyses using the reduced group of students with pretest scores produce qualitatively similar results, whether or not adjustments are made for pretest scores, though the reading difference is somewhat larger for this group (pages 108–127).

Each of these conclusions is based on several analyses that are usually reasonably consistent. Thus, when comparing Immersion and Early-exit Programs in the most compelling portion of the data, there is little indication of differences in mathematics or language scores, but there is some evidence of a difference in reading that favors Early-exit Programs.

What remains is to appraise the evidence that this difference is an effect actually produced by the Early-exit Program. There are three issues: (1) Are there substantial problems in the analytical technique used? (2) Is there evidence specifically presented in the Immersion Report that would lead one to doubt that the difference is an actual effect? (3) Are there sources of uncertainty that are not addressed in the report? All of the panels' answers come from its reading of the Immersion Report, rather than from independent analyses or a direct review of the data.

Concerning the first issue, the panel found no indication of substantial problems in the covariance adjustments that form the basis for the above observations. One might reasonably object to features of some of the reported regression analyses, but the results are highly consistent across a number of different analyses, and thus concerns about a few regression analyses would be unlikely to materially

affect the conclusions. The Immersion Report gives no indication that the regression models were checked using residual analysis and related techniques, but it is unlikely that they would alter the conclusions. The report might have done a better job of documenting the selection of covariates for the analyses, but again, the results are quite consistent across a number of analyses with different choices of covariates.

Concerning the second issue, the panel found no evidence that would lead it to doubt that the difference in reading scores is an actual effect. In other words, there appear to be no internal inconsistencies or unexplained disparities in the data as presented in the report that would lead one to doubt that the difference is a real effect.

Concerning the third issue, there are sources of uncertainty or potential problems that are not addressed. For example, most students left the program early. Also, students who appear similar in observed ways may nonetheless differ in unobserved ways, that is, there may be hidden biases. To some extent, there are unavoidable sources of uncertainty in nonexperimental studies of this sort, and the report falls short of addressing all of these sources of uncertainty. Very little is done to explore or address issues surrounding the extensive incomplete data: Are the students who left the program early similar to those who stayed? Although a complete and certain answer is not possible, simple analyses of the data may contain a partial answer. Finally, the Immersion Report makes no effort to consider the possible impact of unobserved differences between students. Could small unobserved differences between students—that is, small hidden biases—account for the difference in reading scores? Or would it take large hidden biases? How sensitive are the conclusions to hidden bias? Again, there are simple analyses might provide an answer here.

In summary, nothing presented in the Immersion Report leads the panel to doubt the report's conclusion that the Early-exit Programs produce greater achievement than Immersion Programs in reading for K-1 students; however, uncertainties attenuate this conclusion, and these uncertainties might have been partially reduced or at least clarified with fairly simple additional analyses. Nonetheless, the panel concluded this analysis is the most compelling portion of the Immersion Report and judges the report's conclusion to be reasonably credible.

Growth Curve Analyses for Grades 1–3: Watching the Second Half of the Ball Game

The Immersion Report presents a number of growth curve analyses for information on grades 1–3. These analyses look at students' test scores in first grade and see how they change from then until third grade. The panel did not find these analyses to be intuitively compelling in light of potential previous differences among students. Specifically, the level of performance in first grade reflects two very different things: the differences between students prior to the start of the programs, that is, prior to kindergarten, and differences between students' development during kindergarten and first grade, including effects of the bilin-

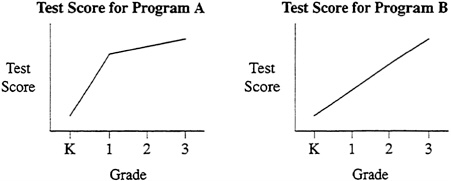

FIGURE 4-1 Hypothetical Student Growth Curves

gual programs under study. A student with better than average performance in first grade may either have started school with various advantages or have developed faster, perhaps due to a good program. These two possible cases are not distinguished in the growth curve analyses.

Figure 4-1 illustrates this point with two hypothetical growth curves for two students in two hypothetical programs (A and B). Both children start in exactly the same place in kindergarten. Both children end up in exactly the same place at the end of third grade. The two programs are equally effective in terms of third-grade achievement. However, if one focuses on grades 1–3, program B looks much more effective. After all, the student in program B was a long way behind in first grade, but has caught up by third grade. This outcome appears to be great progress attributable to program B. If one focuses also on K-1 one sees that the student in program B did less well at first and then merely made up for lost ground in grades 1–3. There are innumerable hypothetical pictures like this one that demonstrate that one cannot measure total accomplishment by looking only at accomplishment in the second half of a process.

If one is interested in performance in third grade, one might look at performance in third grade, with an adjustment for baseline differences in kindergarten. If one is compelled to look at growth curves, the growth curves must extend from kindergarten to third grade; they cannot start at grade one. One needs to be careful that data limitations, such as those imposed by the cohort structure, do not lead to inappropriate analyses.

Programs in Different Schools: Comparing Students Who Are Not Comparable

The comparison of Immersion and Early-exit Programs involved schools that contain only one of the programs. The report states (Ramirez et al., 1991b, pages 171–172):

Even after including the background variables in the model, statistically significant school effects were found … The presence of differences among the one-program schools greatly complicates the comparison of the immersion strategy and early-exit programs. The one-program school analyses cannot

control for school effects because school is confounded with program. As a result, we cannot directly separate out school effects from program effects.

Again, the panel agrees with this conclusion.

The Immersion Report goes on to say that differences in test performance among schools in the same district and program are large and that differences between districts are not much greater than expected based on differences between schools in the same district; the associated analyses are not presented. The analyses in Chapter 4 of Volume II of the report, however, show point estimates of differences between districts that are much larger than point estimates of program effects (often the coefficients of indicator variables representing districts or schools are an order of magnitude larger than the coefficient of the indicator variable for programs). Because differences in test scores between schools with the same program are large, the much smaller difference between the group of schools with Immersion Programs and the group of schools with Early-exit Programs does not necessarily reflect a difference in the programs: it might very easily be part of the substantial difference between schools and the communities they serve.

This issue about the magnitude of effects can be formalized as follows: multiple schools with the same program may be thought of as multiple control groups, and the comparison of these schools may be thought of as a test for hidden bias. From this perspective, there is ample evidence of hidden bias. The Immersion Report takes a different view, building a random-effects model for school-to-school differences and comparing the program difference to the variability between schools. One might argue about which perspective is more appropriate; however, in this case, both approaches tend to give the same answer. Given the large differences between schools with the same type of program, it is not possible to say much about the effectiveness of programs in different schools. Despite the very large number of statistical tests for program differences that were performed, very few yielded significant differences (Ramirez et al., 1991b, page 286): “Almost no program differences were found among the one-program schools.” Furthermore, the Immersion Report summarizes (page 282):

Perhaps the most important result of the analyses of one-program schools is that school-to-school differences are large even within the same district and program. Any program differences are small compared to school differences.

Given that the school-to-school differences are important to the interpretation of the study result, it would have been helpful if the report had presented more information about these differences. Nonetheless, the panel concluded that it is unlikely that this added information would alter the basic finding.

Late-Exit Programs Are Not Compared with Other Programs Using Conventional Analytical Methods

The analysis of the Late-exit Program (in Chapter 5 of Volume II) uses the same conventional methods as Chapters 3 and 4; however, it does not compare Late-exit Programs to Immersion and Early-exit Programs. The report states (Ramirez et al., 1991b, page 287):

The late-exit students were analyzed separately in large part because the districts with late-exit programs had implemented no alternative programs. This makes it impossible to compare students in the late-exit program with students in other programs while controlling for district differences.

Thus, the data on the Late-exit Programs do not contribute to the primary objective of the study, at least from the perspective of conventional methods of statistical analysis. The Immersion Report is probably correct that it is not possible to provide a reasonable comparison of a Late-exit Program in one district with an Immersion or Early-exit Program in another district.

In an attempt to mitigate this seemingly overwhelming problem, the researchers abandoned conventional statistical analysis methods and switched to TAMP (trajectory analysis of matched percentiles) analyses and compared students in different districts (Chapter 6 of Volume II). The panel does not share their view that the differences between districts can be addressed by switching to a different analytical technique even though it appreciates the ingenuity of the TAMP approach (see Appendix B). The TAMP analysis does provide an exploratory method for comparing the changes in multiple populations, but one can only draw inferences from the TAMP graphs if the populations are comparable. The TAMP methodology seems to have been used precisely because the populations were not directly comparable; hence, the conclusions drawn from the TAMP curves are dubious. Any inferences hinted at by a TAMP analysis would still need to be confirmed in a follow-up confirmatory study or analysis.

Sensitivity to Hidden Biases

The Immersion Report does little to investigate whether hidden biases might account for ostensible program effects. For instance, one might ask how much hidden bias would need to be present to account for the difference in reading scores in Immersion and Early-exit Programs? Fairly simple calculations suffice to answer this. Since it is difficult, if not impossible, to assure that small hidden biases are absent, the reader should be warned whether small biases would alter the conclusion. On the other hand, if only very large biases are required to alter the conclusions, the reader would then place greater confidence in the conclusions. A nontechnical discussion of these issues is given in Rosenbaum (1991), and specific methods are illustrated in Rosenbaum (1986, page 219), Rosenbaum and Kreiger (1990), and Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983).

Unit of Analysis: How Far Can One Generalize?

The student is the “unit of analysis” in analyses throughout the Immersion Study, and to this point the panel has adopted the same view. This choice of the unit of analysis has significant consequences for the interpretation of results. Alternative units of analysis would be the classroom, the school, or the school district. The phrase “unit of analysis” is not particularly suggestive of the nature of the issues involved, which are both technical and subject to some debate among

statisticians. This section briefly outlines these issues and then discusses their implications for the interpretation of the Immersion Study.

One common view of the “unit of analysis” issue takes the student as the unit of analysis in order to make statements that generalize to other students, that is, to students not in the Immersion Study. If the student is the unit of analysis, however, then implicitly there is no desire to generalize to other classrooms or teachers, to other schools, or to other school districts. In other words, with the student as the unit of analysis, one asks: “What can one say about what would happen if more students in the same schools attended the same classes with the same teachers?” With the student as the unit of analysis one does not usually ask: “What can one say about what would happen if more students in the other schools attended similar classes with different teachers?” For this question one would take the school as the unit of analysis. In this view, there is no right or wrong choice of a unit of analysis, but each choice is tied both to certain analyses and to certain questions. If one wanted to generalize to other teachers, not those specifically in the Immersion Study, then one would have needed a different unit of analysis and different analytical methods and one would be answering a different question. An unstated premise underpinning this view is that variation or uncertainty arises in statistics principally through sampling: that is, statistical methods are needed for inference because one observes only part of the population, for example, some but not all of the students or some but not all of the teachers.

An alternative perspective sees observational studies such as the Immersion Study as more closely tied to experiments than to sample surveys. In the traditional literature on randomization in experiments, statistical methods are needed for inference not because one observes only part of the population, but because one observes each individual under only one treatment, that is, one observes only one of yI, yE, or yL. In this traditional statistical literature, which dates back to the creator of randomized experiments, Sir R. A. Fisher, one does not assume that the individuals included in an experiment are a sample from a population, and one confines inferences to effects of the treatments on individuals in the study; randomization permits inferences about the effects caused by the treatments, even though individual treatment effects, such as yI-yE, can never be calculated. In somewhat common statistical parlance, the randomization confers internal validity to generalizations of inferences from an experiment. For inferences from observational studies that are used in lieu of experiments, one should therefore be loath to adopt a broader form of generalization. To go from this internal validity to the external validity of inferences for units outside the study would require the random selection of the units within the study from the larger population of interest.

Since the units (students) within other units in the Immersion Study were not drawn at random, the panel believes that it is appropriate, at least at the outset, to restrict attention to an analysis that attends to the internal structure. Then the issue of the unit of analysis divides into three separate questions: “How were treatments assigned to students?” “Do students “interfere” with each other in the sense that

the giving one student a particular treatment affects not only that student but other students as well?” “Are there different versions of the treatment?” The following discussion addresses these questions in turn.

First, how were treatments assigned to students? Were students in the same school divided into groups which received different treatments? In this case, the student would apparently be the unit of analysis. Or were all students in a given school or district given the same treatment? In this case, the school or district would be the unit of analysis. Both types of assignment appear to have occurred in the Immersion Study. Thus, the unit of analysis is the student in those schools that contain both Immersion and Early-exit Programs; but in schools or districts that contain only one program, the unit of analysis is the school or district. Once again, the Immersion Study's reported analyses of programs in the same school seem more appropriate and plausible than analyses that compare programs in different schools or districts.

Second, do students interfere with one another? Does the treatment given to one student affect other students indirectly? It is not possible to answer these questions with a study like the Immersion Study. It is possible, in principle, that students do interfere with each other. This might happen, for example, to a student if Spanish is spoken at home, if the student is rarely asked to speak in class, and when asked says little. In this case, the principal opportunity to practice English may come from speaking with other students. If a student's best friend receives a particular program, this might, in principle, affect the quiet student as well. Typically, a unit of analysis is selected so that units of the selected type do not interfere with one another: that is, units are chosen to formulate the problem so that interference does not arise. For example, students in different schools are not likely to interfere with one another to any significant degree. These observations would argue for the school as the unit of analysis. The alternative is to continue with the student as the unit of analysis but to try to address possible interference in some way. Although doing so is certainly possible, there is little help to be found in the statistical literature.

Third, are there versions of the treatment? As noted above, there do appear to have been different versions of different programs. If the Immersion Study is viewed as several separate horse races between related but not identical treatments (as suggested above), then the student may be the appropriate unit of analysis. If, instead, there is a desire to use the variation between versions of each treatment in an effort to describe variation between programs that may arise in the future, then the school or district has to be the unit of analysis. This latter view leads back to the discussion of the first view of “units of analysis” that began this section.

From a practical point of view, if the unit of analysis for the Immersion Study is anything but the student, the statistician has little with which to work. For instance, if the site is the unit of analysis, the sample size in the Late-exit group is only three sites.

With the student as the unit of analysis, the panel has two major conclusions about what can be learned from the Immersion Study. First, comparisons of two or

more programs within the same school can reasonably view the student as the unit of analysis, with a caveat. Such a comparison is a collection of separate contests between related but not identical treatments as they were implemented in certain specific schools; it provides unconfirmed suggestions about how things would be different with different teachers, in different school districts, or in programs with other incidental differences. Second, comparisons of programs in different schools could use the student as the unit of analysis only if variation in outcomes between schools and districts is adequately controlled by adjustments for covariates, but as discussed above (“Adjusting for Overt Biases”), this does not appear to have been done.

SUGGESTIONS FOR THE FUTURE

Further Analyses of the Current Data Set

The Department of Education provided the panel with data tapes for the Immersion Study; however, the panel was unable to successfully manipulate the data. There were several technical problems relating to the format of the data and the quality of the tape media that interfered with our efforts. We believe that the Immersion Study data are quite valuable and encourage the Department of Education to make the data publicly available in a form that is easy for researchers to use, while protecting confidentiality.

Several further analyses of the data from the Immersion Study would be especially useful in helping one to appraise the findings, particularly the one positive finding of evidence in support of superior reading performance in kindergarten and first-grade for students in Early-exit Programs in comparison to Immersion Programs. Three such analyses are of students who left the study early, of sensitivity to hidden bases, and of school-to-school variations.

Many students left the study early. It would be helpful to know more about how these students differed from those who stayed in the study. Since the panel believes the most credible data comes from the comparison of Immersion and Early-exit Programs in the same schools, information on students who left these schools and whether differences are related to Immersion versus Early-exit would be especially valuable. A simple analysis would describe the baseline characteristics of the students in the four groups:

|

|

Program |

||

|

Characteristic |

Immersion |

Early-exit |

|

|

Stayed in Program |

|

|

|

|

Left Program Early |

|

|

|

Another useful analysis would look at how sensitive the study conclusions are to hidden bias. Students who appear similar on the basis of observed characteristics may differ in ways not observed—there may be hidden bias. How much hidden

bias would need to be present to account for the difference in reading scores in the Immersion and Early-exit Programs? Fairly simple calculations can be done to answer this question. Such sensitivity analyses would be a useful addition, particularly for the comparison of students in Immersion and Early-exit Programs in the same school.

A major issue in Chapters 4 and 5 of Volume II of the Immersion Report is the variation in results from school to school. This issue usually appears as part of complex analyses or is based on results not reported in detail. Some basic data summaries would give a clearer picture of what is happening among schools, even though such information is not likely to alter the basic conclusions of the report.

Suggestions for the Design of Future Studies

The panel's analysis of the Immersion Report leads us to propose several features for future studies. First, future studies should compare competing programs within the same schools. Given the variation in test performance between schools, or perhaps between the communities the schools serve, it is difficult to distinguish program effects from inherent differences between schools and communities when competing programs exist within different schools. Similarly, even within one school, it may be difficult to distinguish program effects from the effects of different teachers. In the Immersion Study, the most credible comparisons were of Immersion and Early-exit Programs in the same schools.

Second, more emphasis should be placed on comparability and data completeness in study designs. There is often a tradeoff between the quality and completeness of data and the degree to which the data represent the whole population of interest. It is easier to ensure data quality if one is working at only a few locations. It is easier to obtain relatively complete data if one selects a fairly stable community than if one studies a large number of typical but perhaps unstable communities. Data completeness is a major problem in both the Longitudinal Study and the Immersion Study. The panel believes the Department of Education, in the programs it supports on the evaluation of program effectiveness, places far too much emphasis on obtaining “representative” data, and not enough emphasis on obtaining complete, high-quality data for a more restrictive population of interest. The panel believes it is better to learn definitely what worked some place than to fail everywhere to learn what works.

National studies of the effects of programs would be much more valuable if more was known about the most effective local programs. One way to achieve this objective would be to work with several population laboratories, as described by Cochran (1965). This means identifying a few communities that are particularly suitable for study, even if they are not nationally representative. A good example of the use of a population laboratory is provided by the Framingham Heart Study. The community of Framingham, just west of Boston, Massachusetts, was selected for a major study of heart disease and related health conditions, not because it was a typical U.S. community, but because is was a stable community. The Framingham

study provided a great deal of valuable data over a long period in part because it was not typical: few people moved away, and all the data came from one place, so there was high data quality and uniformity; only a relatively small number of local officials and physicians were involved in data collection; and so on.

A population laboratory for the evaluation of bilingual education programs would be a community that is unusually stable, with as little migration as possible. It is true that such a community may not be typical, but the panel notes that it is very difficult to study a migrant community over long periods of time. A good study community would also be eager to participate over an extended period, willing to expend effort to produce complete, high-quality data, and flexible about putting in place competing programs with different characteristics.

Third, ideally one would wish to create competing programs for study rather than to find existing programs. The panel believes strongly in turning the ideal into reality. Created programs would have fewer unintended features, so it would be clearer why they succeed or fail. Admittedly, creating programs is more expensive than finding them, but a great deal of money was spent on the Immersion Study, and only a restricted part of the data turned out to be of value. The amount of money spent, with limited benefit, on both the Immersion and Longitudinal Studies would have been sufficient to create a few carefully planned programs within two or three focused population laboratories. Thus, we are suggesting better deployment of allocated funds rather than increased funding.

Created programs have several advantages:

-

Competing programs may be created in the same school, thereby avoiding one of the most serious problems in some of the current data from the Immersion and Longitudinal Studies.

-

The characteristics of the programs can be created to maximize the clarity and impact of the study. For example, the Immersion and Late-exit Programs are polar opposite concepts—if there is a difference between programs, one would expect to see it between these two programs. The existing Immersion and Late-exit Programs are not in the same school district, however, so it hard to compare them. Rather, Immersion Programs were compared with Early-exit Programs, programs that are somewhat in the middle.

-

Programs with the same name would actually be essentially the same program. In contrast, in the Immersion Study, programs called “immersion” differ from each other, as did programs called “early-exit” and “late-exit.”

-

Data collection could be built in as an essential part of the programs.

Creating programs requires cooperation by local schools, parents, and children. This cooperation might be somewhat easier to elicit if resources were available to make the competing experimental programs attractive. Reduced class size in the competing programs, teacher's aides, and adequate administrative support for the burdens of data collection are all ways to make competing programs attractive without favoring any particular program. Participants in such experimental programs should see their participation as yielding added resources, not just added

responsibilities. Competing programs should be sufficiently attractive that many, if not most, parents and children would see participation in any of the competing programs as an improvement over previously available alternatives. In Chapter 5, the panel attempts to provide the groundwork for the discussions that must precede the creation of programs for future studies.

Fourth, the panel believes that, when possible, it is best to run true experiments, in which students are randomly assigned to competing programs within the same school. With experiments, randomization provides a statistical justification for drawing causal conclusions from estimates of differences in outcomes between students in different programs.

Random assignment has long been the norm in medical studies of new drugs, even for life-threatening conditions. This was not always the case and the shift to random assignment required great effort. A key feature for successful implementation of randomization in medical studies is that patients correctly perceive that the quality of care they will receive in either of the competing experimental treatments is at least as good as the care they would receive if they declined to participate. Experiments with human subjects are ethical and practical only when (1) the best treatment is not known, and (2) the competing treatments are all believed or hoped to be at least as beneficial as the standard treatments. In recent years ethical concerns about giving patients an inferior treatment have led to the institution of data, safety, and monitoring committees that stop trials early (and sometimes to an increased reluctance to launch trials) in the face of observational evidence that a new treatment is preferred. In bilingual education such an approach would mean that the competing programs should be seen by all involved as attractive in comparison with what is available outside the experiment and that the study should be designed with sufficient flexibility to allow for changing treatments if one of the programs is clearly superior.

Though randomization is highly desirable, it is not always practical or ethical. An attempt to randomize will fail when an experimenter cannot really control the assignment of treatments to subject. A well-conducted observational study can be of greater value than an unsuccessful attempt to conduct a randomized experiment.

REFERENCES

The definition of a treatment effect used in this chapter was suggested by Neyman (1923) and is now standard in the traditional statistical literature on experimental design; see, for example, Welch (1937), Wilk (1955), and Cox (1958a). Rubin (1974) discusses how the definition is used in the context of observational studies, and Cochran (1965) and Rubin (1984) discuss a broader array of issues of interpretation in such studies. Sir Ronald Fisher (1925) first showed that randomization in experiments provides a formal justification for basing causal inferences on the results of certain statistical procedures; see also Kempthorne (1952), Cox (1958b), and Rubin (1978). Rosenbaum (1984) discusses the consequences of treating outcomes as if they were covariates in the sense of treatments and treat-

ment effects. Campbell (1969) and Rosenbaum (1987) describe the use of multiple control groups to detect hidden bias. Cornfield et al. (1959) provide an illustration of some of the kinds of sensitivity analyses suggested in this chapter. Other useful references on sensitivity include Rosenbaum (1986, 1991). Cox (1958b) discusses the issue of interference between units.

Campbell, D. (1969) Prospective: Artifact and control. In R. Rosenthal and R. Rosnow, eds., Artifact in Behavioral Research. New York: Academic Press.

Cochran, W. G. (1965) The planning of observational studies of human populations (with discussion). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 128, 124–135.

Cornfield, J., Haenszel, W., Hammond, E., and others (1959) Smoking and lung cancer: Recent evidence and a discussion of some questions. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 22, 173–203.

Cox, D. R. (1958a) The interpretation of the effects of non-additivity in the latin square. Biometrika, 45, 69–73.

Cox, D. R. (1958b) The Planning of Experiments. New York: John Wiley.

Fisher, R. A. (1925) Statistical Methods for Research Workers (first ed.). Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

Kempthorne, O. (1952) The Design and Analysis of Experiments. New York: John Wiley.

Neyman, J. (1923) On the application of probability theory to agricultural experiments. Roczniki Nauk Rolniczvch, X, 1–51. English translation: Statistical Science, 1990, 5, 465–480.

Ramirez, D. J., Yuen, S. D., Ramey, D.R., and Pasta, D.J. (1991a) Final report: Longitudinal study of structured-english immersion strategy, early-exit and late-exit transitional bilingual education programs for language-minority children, Volume I. Technical report, Aquirre International, San Mateo, Calif.

Ramirez, D. J., Pasta, D.J., Yuen, S. D., Billings, D.K., and Ramey, D. R. (1991b) Final report: Longitudinal study of structured-english immersion strategy, early-exit and late-exit transitional bilingual education programs for language-minority children, Volume II. Technical report, Aquirre International, San Mateo, Calif.

Rosenbaum, P., and Kreiger, A. (1990) Sensitivity of two-sample permutation inferences in observational studies. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 85, 493–498.

Rosenbaum, P.R. (1984) The consequences of adjustment for a concomitant variable that has been affected by the treatment . Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A, 147, 656–666.

Rosenbaum, P.R. (1986) Dropping out of high school in the United States: An observational study. Journal of Educational Statistics, 11, 207–224.

Rosenbaum, P.R. (1987) The role of a second control group in an observational study (with discussion). Statistical Science, 2, 292–316.

Rosenbaum, P. R. (1991) Discussing hidden bias in observational studies. Annals of Internal Medicine, 115(11), 901–905.

Rosenbaum, P.R., and Rubin, D. B. (1983) Assessing sensitivity to an unobserved binary covariate in an observational study with binary outcome. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 45, 212–218.

Rubin, D. B. (1974) Estimating the causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 66, 688–701.

Rubin, D. B. (1978) Bayesian inference for causal effects: The role of randomization. Annals of Statistics, 6, 34–58.

Rubin, D. B. (1984) William G. Cochran's contributions to the design, analysis, and evaluation of observational studies . In P. S. R. S. Rao and J. Sedransk, eds., W. G. Cochran's Impact on Statistics, pp. 37–69. New York: Wiley.

U.S. Department of Education (1991) The Condition of Bilingual Education in the Nation: A Report to the Congress and the President. Office of the Secretary. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education.

Welch, B. L. (1937) On the z-test in randomized blocks and latin squares. Biometrika, 29, 21–52.

Wilk, M.B. (1955) The randomization analysis of a generalized randomized block design. Biometrika, 42, 70–79.