1

Introduction

Since the beginning of the century, offshore drilling for oil and gas has made an important contribution to the energy resources of the United States. The need to balance the value of offshore oil and gas resources against the potential for the environmental damage that can attend their recovery has become increasingly recognized in federal law and in the national debate over energy.

The federal offshore leasing program has been a source of controversy since the 1940s, when the federal government began to assert public ownership of offshore resources. Conflicts pertained mostly to questions of the ownership of resources and to the distribution of costs and benefits among local, state, and federal governments. Potential environmental damage from the activities associated with oil and gas leasing of the outer continental shelf (OCS) also was largely a local concern until 1969, when a spill resulted from a blowout at a Union Oil platform. Over 3 million gallons of oil has been released into California's Santa Barbara Channel (MMS, 1991a) and the accident brought environmental concerns to national attention (Congressional and Administrative News of the U.S. Code, 1978). The spill affected 150 miles of coastline (Nash et al., 1972). Other oil and gas accidents have caught the public's attention, even though they have not involved the U.S. OCS. Two accidents drew wide public notice in the United States. The first, on June 3, 1979, was the blowout of the Mexican exploratory offshore well Ixtoc I. It released more than 150 million gallons (500,000 tons) of oil and natural gas—at the time the largest accidental oil spill in history1 (NRC, 1983a). The second was the grounding of the tanker Exxon Valdez on March 24, 1989. It released about 11 million gallons of North Slope crude oil into Alaska's Prince William Sound. Even though the Exxon Valdez accident did not involve OCS oil, its effects on the OCS debate are clear.

The U.S. petroleum resource is valuable. From 1954 through 1990, the last year for which there are statistics, the offshore petroleum industry provided almost 7.5% (8.8 billion barrels2) of all domestic oil and about 14% (93 trillion cubic feet) of domestic natural gas. It accounted for more than $97 billion in revenue from cash bonuses, rental payments, and oil and gas royalties (MMS, 1991b). In 1990 alone, 12.1% (324 million barrels) of domestically produced oil came from the outer continental shelf, and it was the source of 27.6% (5.1 billion cubic feet) of domestic natural gas. In 1990, it provided more than $3 billion (Table 1-1) of the total federal revenue of more than $1 trillion, or 74% of all royalties collected (MMS, 1991b, c).

TABLE 1-1 OCS Revenue by Region, 1990

|

Region |

Amount |

|

Gulf of Mexico |

$3,237,287,758 |

|

Pacific |

113,932,232 |

|

Atlantic |

1,179,648 |

|

Alaska |

15,339,181 |

|

Total |

$3,367,738,819 |

|

Source: MMS, 1991b |

|

ACTIVITIES ON THE OUTER CONTINENTAL SHELF

Management of OCS Activities

OCS leasing is managed by the Minerals Management Service (MMS) of the Department of the Interior. MMS was formed in 1982 to consolidate responsibility for offshore oil and gas development in one agency. Before 1982, the task was shared by the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Geological Survey. Federal responsibility for the development of mineral resources and the conservation of natural resources on the outer continental shelf was established by the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA) of 1953 as amended in 1978 (43 U.S.C. 1331-1356, 1801-1866) and the by Submerged Lands Act of 1953 (43 U.S.C. 1301-1315).

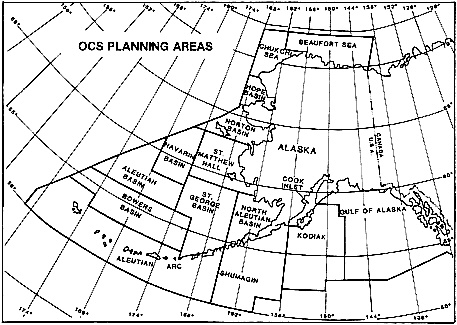

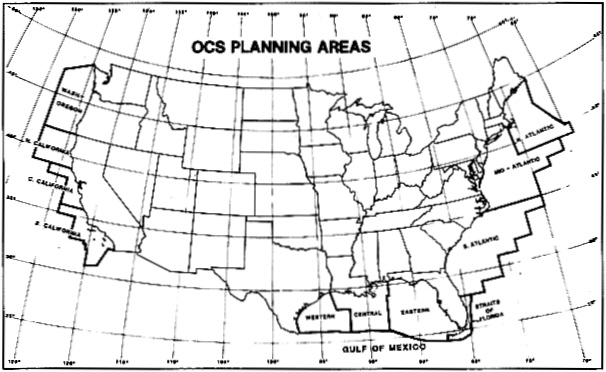

The schedule for the sale of leasing rights is established in accordance with a five-year plan that stipulates the size, timing, and location of proposed leasing activities. The plan is developed in a two-year process that includes consultation with the governments of coastal states, federal agencies, and the public. Beginning in 1983, MMS offered lease sales for entire areas rather than for selected tracts so that the number of blocks and leases was increased and drilling of more exploratory wells in frontier areas, such as areas of deep water, was encouraged. (The current plan proposes a new "area evaluation and decision process" to be more selective than earlier plans were about which areas will be available for lease and more responsive to the views of affected parties, except in the central and western Gulf of Mexico, where nearly all unleased acreage will be offered annually.) The current proposed plan, effective from 1992 to 1997, lists 18 sales in 11 of the 26 OCS planning areas (see Figures 1-1 and 1-2) (MMS, 1992a). Other areas were designated for possible study subject to leasing decision needs and budgetary constraints.

Extent of the Leasing Program

Between 1954 and 1990, 102 lease sales offered 148,456 OCS tracts that contain 781,684,261 acres in four regions—Alaska, the Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Pacific. Only 12,326 (8.3%) of those tracts—in all, 63,512,799 acres (8.1% of the total acreage offered—were actually leased. Table 1-2 provides a regional breakdown of lease offerings and sales between 1954 and 1990.

In 1990, of 6,163 active leases, 1,717 (25%; 8,044,618 acres) were producing oil or gas. To date, all producing leases have been in California or in the Gulf of Mexico, although some in Alaska have proven reserves. OCS production first began in the Gulf of Mexico in 1954. California OCS wells did not begin to produce until 1968. Tracts on federal lands in the Alaska and Atlantic regions were first leased in 1976 but have not produced to date. There has been considerable production in state tracts in Alaska, California, and the Gulf of Mexico. Table 1-3 shows, by region, the number of active leases in 1990. Through 1990, 4,601 platforms had been built and 788 had been removed, leaving 3,813 in place (MMS, 1991a). All but 23 of the platforms were in the Gulf of Mexico.

TABLE 1-2 OCS Lease Offerings and Sales, 1954-1990

|

|

|

Leases Offered |

Leases Issued |

Percentage Leased |

|||

|

Region |

Number of Sales |

Tracts |

Acres |

Tracts |

Acres |

Tracts |

Acres |

|

Alaska |

13 |

17,451 |

96,232,365 |

1,480 |

8,175,771 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

|

Atlantic |

8 |

8,773 |

49,317,339 |

384 |

2,186,183 |

4.4 |

4.4 |

|

Gulf of Mexico |

70 |

120,356 |

626,464,878 |

10,002 |

50,667,765 |

8.3 |

8.1 |

|

Pacific |

11 |

1,876 |

9,669,679 |

460 |

2,483,080 |

24.5 |

25.7 |

|

TOTAL |

102 |

148,456 |

781,684,261 |

*12,326 |

*63,512,799 |

8.3 |

8.1 |

|

*The Department has held 2 reoffering sales of onshore oil and gas lease areas: RS-1 reoffered 175 tracts (996,308 acres), Alaska; RS-2 reoffered 140 tracts (785,091 acres), Alaska; 155 tracts (822,444 acres), mid-Atlantic; 232 tracts (1,320,819 acres), South Atlantic; and 27 tracts (153,716 acres), northern and central California. Source: MMS, 1991a. |

|||||||

TABLE 1-3 Active OCS Leases, 1992

|

Region |

Active Leases |

Percentage of Active Leases |

Acres Leased |

Percentage of Acres Leased |

|

Alaska |

894 |

14.5 |

4,955,874 |

15.7 |

|

Atlantic |

61 |

1.0 |

347,284 |

1.1 |

|

Gulf of Mexico |

5,098 |

82.7 |

25,746,739 |

81.4 |

|

Pacific |

94 |

1.5 |

475,950 |

1.5 |

|

Total |

6,147 |

100.0 |

31,525,847 |

100.0 |

|

Source: MMS, 1991a. |

||||

Environmental Concerns

Potential effects of oil spills that result from OCS development and production on coastal resources such as fisheries, endangered species, and marine wildlife are a major source of public concern. Other sources of potential harm associated with OCS development include the discharge of produced water and drilling muds, the chronic loss of oil at the drilling site, and the damage associated with construction of support facilities in coastal areas. Seismic surveys, erection of platforms, and placement of pipelines can interfere with commercial, recreational, and subsistence fishing. Vessel traffic and the laying of pipelines contribute to coastal erosion, especially in the marshy areas of the Gulf of Mexico (Turner and Cahoon, 1988). The potential for long-term,

chronic environmental damage also exists, and many potential and actual effects are discussed in earlier NRC reports (NRC, 1983a, 1985, 1989a, 1991b).

Potential socioeconomic effects—changes to the human environment—attend all phases of OCS activity. The concept of the human environment, as defined by OCSLA as amended in 1978, includes the ''physical, social, and economic components, conditions, and factors which interactively determine the state, condition, and quality of living conditions, employment, and health of those affected, directly or indirectly, by activities occurring on the outer Continental Shelf'' (43 U.S.C. §1331 (i)). This concept is further defined in Chapter 2 of this report and discussed more fully in Appendix B. Some socioeconomic effects result directly from biological and physical changes, or are the result of public concerns about them. Conflicts over the distribution of the costs and benefits of OCS activities, space conflicts between different users of the ocean, siting of industrial facilities in coastal areas, alterations to subsistence fishing in rural Alaska, economic dependence on OCS activities in coastal communities, impacts on educational levels, changes in the tourism industry, and fear and uncertainty about anticipated changes in the quality of life when a lease sale is announced can occur.

The effects on the physical environment of oil spills and other OCS operations have been the subject of previous NRC reviews (NRC, 1975, 1978, 1983a, 1985, 1989a, 1990, 1991a); this report addresses their effects on the human environment.

THE ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES PROGRAM

Mandate

As amended in 1978, OCSLA (43 U.S.C. §1344) requires MMS to manage the oil and gas leasing program in light of the economic, social, and environmental value of the renewable and nonrenewable resources in the outer continental shelf; the marine, coastal, and human environments that could be affected; the laws, goals, and policies of affected states; and the equitable sharing of developmental benefits and environmental risks among the various regions. The timing of leases and their locations must be selected, to the maximum extent practicable, to balance the potential for environmental damage with the potential for extraction of oil and gas.

To balance the benefits of the leasing program with environmental risks, MMS must conduct studies that develop the information needed for "the assessment and management of environmental impacts on the human, marine, and coastal environments of the OCS and the coastal areas that may be affected by oil and gas development" (43 U.S.C. Sec. 1346 (a)(1)). MMS also must monitor the human, marine, and coastal environments of leased areas "in a manner designed to provide time-series and data-trend information which can be used for comparison with any previously collected data for the purpose of identifying any significant changes in the quality and productivity of such environments, for determining trends in the areas studied and monitored, and for designing experiments to identify the causes of such changes" (43 U.S.C. §1346 (b)).

In addition, the secretary of the interior must "submit to the Congress and make available to the general public an assessment of the cumulative effect of activities…on the human, marine, and coastal environments" (43 U.S.C. §1346 (e)). The same section requires the secretary to establish procedures for conducting the required studies. OCSLA as amended in 1978 (43 U.S.C. §1334 (a)(8)) requires the secretary to regulate activities to ensure that they do not prevent attainment of the Clean Air Act's National Ambient Air Quality Standards (P.L. 101-549 §109).

The secretary must then use the information required by these sections to support leasing decisions, to promulgate regulations, to set lease terms, and to establish operating procedures for OCS

activities (Congressional and Administrative News of the U.S. Code, 1978; 43 U.S.C. §1346 (d)). Information from environmental studies is used to support permitting decisions as well. Separate permits are required before geological and geophysical surveys may be conducted or exploration, development, or production begin. Exploration, development, and production plans must be submitted to MMS together with environmental reports and certificates of consistency with state coastal zone management plans.

The information also serves as the basis for ensuring compliance with other environmental laws, such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) (42 U.S.C. §4321-4347), which requires federal agencies to "utilize a systematic and inter-disciplinary approach which will insure the integrated use of critical and social sciences and the environmental design arts in planning and in decision making which may have an impact on man's environment" and to prepare environmental impact statements based on that information before taking major federal action. In its environmental impact statements, the development agency is required to consider realistic alternatives to proposed actions. Other environmental laws applicable to OCS activities include the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (16 U.S.C. §1531-1543, 50 CFR 17) and the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 (16 U.S.C. §1361-1407, 50 CFR 216), which require MMS to consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service to ensure that OCS activities do not destroy critical habitat or cause other significant harm to marine mammals and endangered species. The Coastal Zone Management Act (16 U.S.C. §1451-1464) as amended in 1990 makes leasing decisions subject to consistency certification. The Federal Water Pollution Control Act Amendments of 1972 (33 U.S.C. §1251-1375; P.L. 92-500), the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (16 U.S.C. §3101-3233; P.L. 96-487), the National Historic Preservation Act (16 U.S.C. §470-470w6; P.L. 89-665), and the Marine Protection, Research and Sanctuaries Act of 1972 (33 U.S.C. §1401-1445; P.L. 92-352) also affect offshore leasing.

Program History

The Environmental Studies Program (ESP) was established in 1973, in large part to comply with the requirements of NEPA. A more extensive history of the federal government's OCS program is given in Appendix C. From its inception (it was administered until 1981 by the Bureau of Land Management) through 1991, ESP has invested more than $539 million in research funds. Annual appropriations for the program have averaged about $30 million but recently have declined. Most studies are performed by external contractors (MMS, 1988a). MMS's Branch of Environmental Studies in Herndon, Virginia, coordinates the programs of the four regions: Alaska, the Pacific, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Atlantic. The regional offices (in Anchorage; Ventura, California; New Orleans, Louisiana; and Herndon, Virginia) define and contract for most of the studies. Socioeconomic studies have accounted for approximately 4% of ESP's budget, an average of less than $1.5 million a year. Almost 70% of the national budget for socioeconomic studies has been spent in the Alaska region.

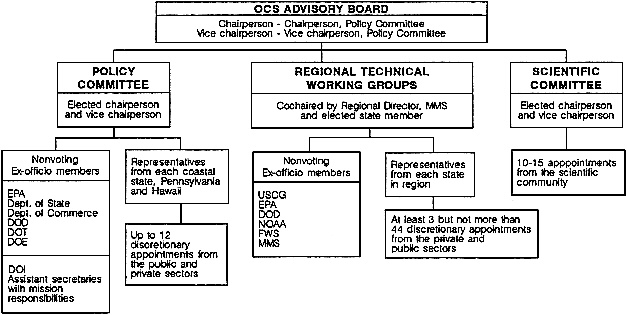

In response to an NRC review (NRC, 1978), the program was restructured in 1978 to provide more immediately usable results for leasing and management decisions and to provide a framework for establishing study priorities (MMS, 1987b). A more detailed discussion of the regional programs appears in Chapter 4. Under the mandate to establish procedures for conducting environmental studies, guidance was developed by an OCS ad hoc advisory committee and published in "Study Design for Resource Management Decisions: OCS Oil and Gas Development and the Environment" (BLM, 1978); it was adopted by the OCS Advisory Board (Figure 1-3) on April 29, 1978. The document requires identification of management decisions and development of studies to provide the information needed for making those decisions.

The national OCS Advisory Board was established by the secretary of the interior in 1975 to provide guidance and recommendations on the leasing and development process, to receive comments and recommendations from state officials and other interested parties, and to provide a forum for discussion among federal agencies. The board consists of a policy committee, a scientific committee, and at least one regional technical working group for each region (the Atlantic region has three because it has 14 coastal states). The board reviews political, scientific, and technical aspects of OCS development and attempts to balance state, local, federal, public, and private interests. The scientific committee was established specifically to provide guidance and to review the ESP. The regional

Figure 1-3

Outer Continental Shelf Advisory Board organizational chart. Source: MMS, 1987a.

technical working groups make recommendations for the entire leasing and development process (including the ESP) (MMS, 1987c).

The goals of the ESP are as follows (Aurand, 1988):

-

Provide information that can be used to predict the effects of OCS oil and gas development.

-

Provide information about the ways and the extent to which OCS development can affect the human, marine, biological, and coastal environments.

-

Ensure that information that is already available or being collected for the program is in a form that can be used in the decision-making process associated with a specific leasing action or with longer term OCS management responsibilities.

-

Provide a basis for future environmental monitoring of OCS operations, including assessments of the short-term and long-term effects attributable to the OCS oil and gas program.

THIS REPORT

In 1986, MMS requested a review of ESP that would recommend future directions. In response, the NRC Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology formed the Committee to Review the Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Studies Program. Its members are experts in ecology, energy production, geochemistry, marine geophysics, oilfield technology, geology, law, physical and biological oceanography, public policy, and resource management. Its charge is fourfold:

-

Provide an unbiased, independent evaluation of the adequacy and applicability of the studies used to inform leasing decisions and the prediction and management of the environmental effects of OCS oil and gas activities.

-

Offer specific recommendations for future ESP studies.

-

Identify issues about which there is sufficient information.

-

Provide a state-of-the-art review of the available information relevant to the program.

Three panels were established to examine the specific subject areas of physical oceanography, ecology, and socioeconomics (NRC, 1990, 1991a). This report evaluates the ESP's socioeconomic studies and includes recommendations for areas the program should pursue.

The main objectives of the Socioeconomics Panel's evaluation are as follows:

-

Provide an unbiased, independent evaluation of the adequacy and applicability of ESP's socioeconomic studies.

-

Provide specific recommendations for future ESP socioeconomic studies.

-

Provide a state-of-the-art overview of available information on each major issue reviewed, based on MMS studies, other relevant data bases, and the technical literature.

The panel's members recognize that ESP is not intended to be a broad, general science program, but is designed instead to study questions about the environmental and socioeconomic effects of oil and gas exploration and production. Nonetheless, the answers to those questions must be based on sound science.

The remainder of this chapter describes ESP. Chapter 2 describes the potential effects of OCS activities on the human environment. Chapter 3 describes an ideal socioeconomic studies program. Chapter 4 comments on the current program in the four regions. Conclusions and recommendations are provided in Chapter 5. Appendix B provides an extensive treatment of the human environment and effects on it. Appendix C discusses the evolution of the federal OCS program from national and regional perspectives.

PLANNING AND PROCUREMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES

Development of a Studies Plan

In 1978, MMS developed a framework for setting study priorities, based on the importance of the study for decision making, timeliness, generic applicability of results, availability of information, and applicability to issues of regional or program concern. To develop a list of topics, MMS identifies issues, primarily through the regional offices and with the help of advisory groups (including the regional technical working groups and the scientific committee) and interested parties

(environmental groups and industry associations). ESP staff members then translate the issues into questions that reflect the information needed for decision making.

Regional MMS offices, with help from the advisory groups, evaluate the resulting list of study topics for scientific and technical feasibility, availability of information, scientific merit, and the time during which or by which the information is needed. The list of study topics is reviewed by other federal agencies and by scientists in the academic community, in state and local governments, and in industry. After the review is finished, each regional office submits a draft regional studies plan to the Branch of Environmental Studies in Herndon, VA. The plan includes a statement of regional needs for information, the regional perspective on the priorities of these needs, a ranked list of proposed study topics, and a brief description of the rationale for each proposed study. The branch in consultation with the regions develops a national studies list from the proposed study topics and ranks them for funding priority based on criteria that include consideration of how the proposed study fulfills legislative mandates and other legal requirements and whether the study will be completed in time for use in specific leasing decisions. Contracts for the studies are then funded by MMS from its appropriated budget according to rank, until funds are exhausted. Since 1982, MMS has provided support for the review, publication, and dissemination of ESP results, including publication in peer-reviewed journals (pers. comm., MMS, 1989). Study contracts are awarded to private industry, universities, research institutes, and nonprofit organizations. The procurement process normally is competitive and is based on requests for proposals and associated statements of work prepared by MMS.

Implementation of Studies According to Lease Sale Schedules

The planning process for individual studies has been governed primarily by a lease sale schedule, which is established in a five-year planning document. Studies must begin well in advance of a lease sale or any other decision they are intended to support if they are to be useful. A prelease, 15-month-long study normally would be included in a regional studies plan approximately 34 months before the beginning of the lease sale process, which begins with the identification of areas that are believed to contain oil or gas. Table 1-4 is a sample schedule for a prelease study (pers. comm., MMS, 1988); the actual timing varies for individual studies and lease sales.3

WHY MMS NEEDS SOCIOECONOMICS INFORMATION

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act as amended in 1978 mandates a balance between the use of mineral resources and the protection of the human, marine, and coastal environments. Thus, compliance with OCSLA requires the government to have scientific information, including socioeconomic information.

As an example of a need for socioeconomic information, we mention MMS's frequent statements that areas have been excluded from consideration for leasing because of their "environmental sensitivity" (the "flower gardens," a biologically diverse area of the seafloor in the

TABLE 1-4 Planning and Implementation Steps in the OCS ESP and Lease Sale Process

|

Month |

Step |

|

-34 |

Draft regional study plan. |

|

-30 |

Final regional study plan. |

|

-27 |

National study plan. |

|

-20 |

Procurement plan. |

|

-17 |

Draft statement of work. |

|

-12 |

Final statement of work. |

|

-7 |

Request for proposal. |

|

-3 |

Contract. |

|

0 |

Area identified. |

|

1 |

Call for information: MMS publishes notice of intent to prepare EIS in the Federal Register. Industry invited to indicate areas of interest. Interested parties comment on topics and areas of concern. No decision is made about proceeding with sale. |

|

5-9 |

Identification of area to be analyzed in EIS, identification of alternatives for EIS, estimation of resources, and preparation of oil spill report for proposed action and for alternatives. Draft report of study results. |

|

12 |

Draft EIS and final report of study results to describe planning area, analyze potential environmental effects of oil and gas leasing, and discuss mitigating measures proposed to resolve conflicts. Public comment period. |

|

13 |

Public hearing—opportunity for oral comments on draft EIS. |

|

14 |

Close of comment period on draft EIS. |

|

18 |

Final EIS to assess comments from the state and the public. Secretarial issue document prepared to analyze all issues involved in the proposed sale and possible coastal zone consistency conflicts. The SID and the EIS are sent for review by the assistant secretary and for decision on whether to issue a proposed notice of sale. |

|

19 |

Proposed notice of sale details terms and conditions of proposed sale, blocks proposed for leasing, stipulations and other mitigating measures to be required, and proposed bidding systems |

|

21 |

Governors' comments used by MMS to develop recommendations to the secretary. SID and final EIS sent to the secretary. The secretary is required to accept the recommendations of a governor if he determines that they provide a reasonable balance between the national and state interest. |

|

22 |

Final notice of sale published at least 30 days before sale, specifies date, time, location, blocks to be offered, and terms and conditions of sale. |

|

23 |

Sale—sealed bids opened and read by regional director. |

|

24 |

Bid review—high bids evaluated to ensure receipt of fair market value. Sale results also reviewed by U.S. Department of Justice to ensure that lease awards do not violate antitrust laws. |

|

25 |

Leases issued—bids accepted or rejected within 90 days of receipt. Leases issued for accepted bids 30 to 60 days after sale. |

|

In this example, five years elapse from the completion of the draft regional study plan to the lease sale. The postlease process includes evaluation of the exploration plan and approval for a drilling permit, evaluation and approval of the development and production plan, issuance of a pipeline permit, and termination or expiration of the lease. Source: Information provided to NRC staff by MMS, 1988. |

|

Gulf of Mexico, for example). President George Bush used that reason, among others, for deferring Sale 116, part 2, in a June 26, 1990, decision (Bush, 1990). Although we are not aware of any case where it has been used, socioeconomic information is needed in the same way to evaluate whether an area should be excluded from lease schedules. For example, onshore development might threaten a unique or valuable cultural community or recreational area or the threat of a spill would endanger a unique or valuable economic or cultural (including subsistence) activity. But without socioeconomic information, the necessary evaluations cannot be made.

Socioeconomic information also is needed to set the terms of OCS operations and to manage the effects of OCS activities (an example is seasonal drilling restrictions imposed by MMS in the Beaufort Sea to avoid effects on migrations of bowhead whales). Otherwise, it is impossible to influence the degree to which OCS activities can alter local and regional economies and social systems or to provide credible rules for dealing with such effects. Finally, the body of socioeconomic information includes people's concerns, fears, and desires about OCS oil and gas operations, and accounting for that information seems to be a prerequisite for the successful operation of an OCS oil and gas program.

What Information is Needed?

The next step is the question of the basic identification of the information needed. In the broadest sense, decision makers need enough information to predict what might be affected by OCS activities and to assess the effects of past OCS projects. A basic inventory of social, cultural, and economic variables would include identification of interests that might be affected. A general characterization of the local population would contain data about age, gender, income, occupation, religion, ethnicity, and world-view; attitudes toward the coastal environment, toward OCS activities, and toward government decision making; social arrangements; institutional arrangements; and the uses of the coastal and marine environments. Also needed is information about how the various stages of OCS activities might affect those social and economic variables. This last area would include an analysis of potential long-term and cumulative effects.

Information on the variables can be obtained from published studies, surveys, interviews, and government records. Potential OCS effects in an area can be elucidated by the study of current and past OCS activities elsewhere. Although in many cases such information can be obtained from prior studies, new studies will always be required, because all cases and periods differ in some ways.

Criteria for Judging the Adequacy of Scientific Information

The panel's operational definition of "adequacy" for scientific information has two aspects: completeness and scientific quality.

Completeness

The body of scientific information grows through research and discovery. Recognizing this continuing process, the panel's criteria for completeness require appropriate breadth and depth of basic scientific information in all relevant disciplines needed to elucidate the environmental risks associated with OCS decisions. These criteria are described in Chapters 3 and 4.

Scientific Quality

The standards of scientific quality are reproducibility, reliability, and validity of measurements and analyses, including appropriateness of methods and subject. The measure of scientific quality used by the panel was whether the methods described represent the current state of good practice in the scientific field (whether they would be likely to pass peer review). This does not imply that the objective is publication in a peer-reviewed journal, but rather that the quality of the data and scientific interpretations used in the studies that support OCS decisions should meet this basic scientific standard.