Introduction

In 1956 John Greenfield was handed a problem: to grow sugarcane on the hills of Fiji. With all the flat land fully used, his company had resolved to expand production up the slopes.

The trouble was that the hillsides on that Pacific island nation were too dry for sugarcane—one of the thirstiest of crops—and the soils were too erodible. Putting cane fields on the slopes could be disastrous to the company, the cultivators, and the country.

Everyone but Greenfield's boss knew that there was no chance of farming those lands without bringing on devastating losses of soil. Even Greenfield thought so, but he is a persistent, no-nonsense sort, and he set about testing all kinds of methods in the hope that one of them just possibly might work.

One of the methods involved bulldozing broad dirt barriers (bunds or berms) along the contours. That was the standard process for controlling erosion in the commercial croplands of most parts of the world. Another method involved a coarse grass called vetiver (Vetiveria zizanioides ), the use of which was virtually unknown.

Greenfield located the vetiver plants growing beside a nearby highway. He had his work crews dig them up, break off slips, and jab the slips side by side into the soil to form lines across the hillsides. It seemed pretty hopeless to expect lines of grass just one plant wide to stop the movement of soil, but he had heard that something similar had been successful in the Caribbean before World War II.

The vetiver slips quickly took root and grew together to form continuous bands along the contour. To everyone's surprise the runoff that normally poured off during tropical storms was slowed down, spread out, and even held back behind the "botanical dams." It took hours to seep through one of the dense walls of stiff stalks (eventually about a meter wide), only to be checked again by the next one down the slope. In consequence, most of the moisture had no chance to rush into the streams below; instead, it soaked into the slopes where it had fallen. More importantly, though, the soil was prevented from leaving the site; it settled out of the stalled runoff and lodged behind the grass walls.

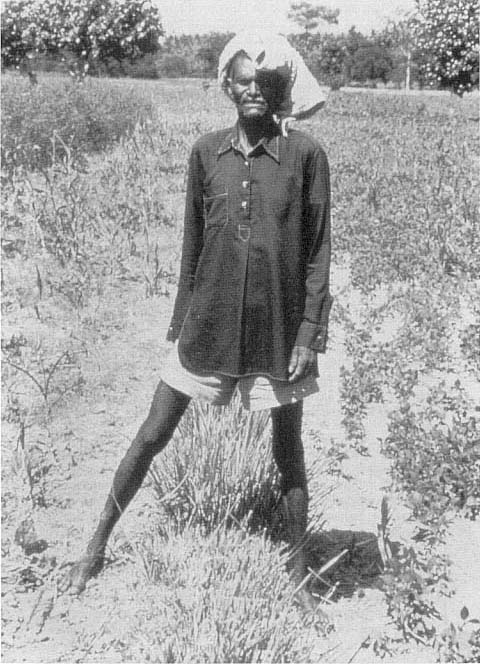

Rakiraki, Fiji. What had been smooth, steep (50-percent) slopes turned into tall terraces fronted by dense stands of grass when vetiver hedges were established here in the 1950s. In the years since, the terraces have grown almost 2 m high in some places. Soil losses have been blocked and stable natural terraces formed, all at little or no cost to the farmer. (D.E.K. Miller)

The full significance of this eluded him until the area was hit by one of the highest intensity storms in Fiji history: 500 mm of rain fell in just 3 hours. Water poured over the top of the vetiver hedges "like a tidal wave," but the plants remained in place, undamaged, and unbreached. Of greater consequence, however, was the fact that the water did not start cutting gullies because the bands of vegetation both robbed it of its force and kept it spread evenly across the slopes as it had fallen.

Greenfield's bulldozed earthworks, on the other hand, did not fare so well. Water built up behind them until the weakest spot could hold no longer. Then, the whole dammed-up body of runoff cascaded through the breach, gashing jagged gullies into the erodible slopes below.

After that experience there was little question about which system to pursue. Indeed, the vetiver hedges succeeded so well at both stopping erosion and increasing soil moisture that sugarcane production quickly expanded out of the flats and up the slopes. Some was produced on grades as steep as 100 percent (45°) and without obvious soil loss. Greenfield's boss was right—it could be done!

Greenfield eventually went on to other projects in various countries and spent a long career advising agricultural programs throughout the tropics. In 1985, the World Bank sent him to India as part of an effort to improve productivity in the rundown, rainfed farming areas of four states. In this region, making up much of central India, thousands of small subsistence farms were being ravaged by erosion. Their soils were scarred, thinned, and so quick to dry out that if the rains were interrupted—even briefly—the crops quickly died. When he saw the situation, Greenfield thought of vetiver; if it could benefit a remote Pacific island, perhaps it could benefit India as well.

He described the vetiver concept and related his former experiences to Richard Grimshaw, his new boss in India. It was an opportune time: the project was not working well; the subsistence farms were still eroding and their yields were still low and woefully unreliable. Grimshaw had Greenfield return to Fiji to make a video showing what had happened to his hillside hedges.

To Greenfield's satisfaction, his old grass strips on the northern shore of Fiji's main island were still standing, still protecting the slopes, and still producing excellent sugarcane crops despite three decades of

almost complete neglect. Moreover, no one was concerned about erosion—the fact that it had even existed there had been forgotten.

However, the slopes no longer looked as they had when he started. They had been transformed into terraces. Tons of silt had built up behind each line of grass. The area now was composed of strips of flat land behind grassy banks up to 2 m tall.

Back in India, Greenfield's videotape was a big hit, and Grimshaw agreed to give vetiver a try. The plant is native to India (where it is normally called "khus" or "khus khus"), and samples were readily obtained from Karnataka State. A huge nursery—covering 8 hectares—was established near Bhopal, and Greenfield and his colleagues went out to persuade farmers to plant hedges across their sandy, red, eroding land. (The videotape helped immensely, especially because the farmers on Fiji had vividly narrated their experiences in Hindi.)

After 4 years—3 of them involving some of the severest droughts on record—the results were so promising that vetiver seemed like a major breakthrough.

In Maharashtra State, lines of the grass trapped 25 cm of silt in 2 months. On the notorious black soils of Karnataka, silt started forming behind a 3-month-old hedge, and the soil loss dropped from 11 tons per hectare to 3 tons per hectare. On the experimental farm at Sehore University, the average silt buildup behind vetiver lines during the rainy season was 10 cm. Some hedges accumulated as much as 30 cm of soil in a year.

What is more, vetiver held back more than just soil. The moisture that normally gushed off the land in flash floods was also trapped—or at least slowed down. There was no way to measure the exact amount; however, plenty of anecdotal information attested to vetiver's remarkable ability to hold runoff on the slopes. On one droughty Indian catchment, for instance, farmers found they could grow mango trees for the first time. In several villages, the water level in the wells rose dramatically after vetiver hedges were put in. In Gundalpet, for example, farmers had water at 8 m depth; wells in nearby villages were dry down to 20 m. On lands in Andhra Pradesh that had been abandoned 12 years earlier as being too dry for farming, farmers put in vetiver and successfully grew millet and castor once again. In several places, farmers with vetiver lines got a harvest where their neighbors got only crop failures. None of this, it should be noted, was due to vetiver alone. It was the combination of the grass and the contour farming, which it induced and stabilized, that jointly made the difference.

One of the most unexpected successes was on black cotton soils. These "vertisols" cover 10 million hectares of central India and could be a major source of food, but their physical properties are such that they can be used for only a fraction of the year. During the rainy

season, when farming should be most productive, they are too sticky even to walk on. Barriers such as berms or bunds tend to worsen the waterlogging. Vetiver, however, allowed excess water to pass through and didn't upset the drainage. Greenfield noted that, after rain, farmers could walk right up to a vetiver hedge, but couldn't get closer to a berm than 40 m. He was so impressed that he predicted vetiver grass would be the answer for bringing India's vertisols into year-round production, resulting in immense benefit to the nation.

Although initially the project staff almost had to force their planting materials onto the farmers, soon the farmers were clamoring for it. Several states—including Orissa, Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan, and Gujarat—also initiated their own vetiver projects. The main constraint to the wider adoption of the method quickly became a lack of nurseries to keep up with the demand for planting materials.

Ironically, after about 4 years of effort, agriculturists in Karnataka stumbled over the fact that many farmers in a particular part of their own state had been using vetiver hedges all along. In fact, throughout the four southern states, people had employed strips of this grass for

|

St. Vincent's Vetiver The following is adapted from John Greenfield's report of a trip to inspect the use of vetiver on the Caribbean nation of St. Vincent in 1989. He arrived at a time when a large-scale erosion-control scheme using bulldozers and expensive terracing, to be financed with foreign capital, was being proposed to the people there. Vetiver grass was introduced to St. Vincent as the major soil conservation measure more than 50 years ago. It was used primarily in the sugar industry to stabilize fields of sugarcane, but found its way all over the island as a stabilizer of road cuttings, driveways, pathways, and tracks along hillsides. Whoever introduced the system did an excellent job, as virtually all the small farmers put their vetiver grass plantings on the contour. This, together with the resulting contour farming, has saved St. Vincent from the ravages of soil erosion. Throughout St. Vincent, I stopped to talk to farmers, and the general consensus was, "surely you haven't come all this way to tell us about khus-khus (as it is called locally); we have known how good it is for over 50 years!" I drove up the leeward coast of St. Vincent with the government official responsible for soil conservation, Mr. Conrad Simon of the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Agriculture. We visited one of the old sugar plantations (now abandoned) where vetiver grass |

at least 100, and maybe even 200, years. However, they used them primarily to denote the edges of farms. Investigation showed that where the boundaries crossed slopes the hedges held back soil on the upper side. Recognizing the significance of this, a few of the more astute farmers had intentionally planted vetiver across the middle of their slopes. But this was the exception; by and large, the grass's environmental benefits lay unappreciated.

As all these results became apparent, Greenfield, Grimshaw, and most of the other observers became extremely excited. If this little-known grass could benefit some of the worst areas of central India, surely it could benefit other parts of the world. Indeed, here was something that might underpin millions of farms and forests, not to mention watersheds, rivers, reservoirs, harbors, highways, bridges, canals, and other facilities affected by erosion. Perhaps the whole face of the tropics might be changed for the better by the narrow strips of this grass. Perhaps at last there was a way to keep soil on the hills where it was needed and out of the waterways where it was not. More importantly, perhaps it offered a sustainable method of moisture

|

barriers had formed stable terraces 4 m high. After 50 years, the grass was still active, and there was no sign of erosion. In other areas, vetiver barriers planted on more than 100 percent slopes were providing full protection against erosion and had been doing so for years. The only area where I noticed erosion starting was where people had pulled out the vetiver on the "riser" of a terrace and planted food crops. Major rills had developed down the face, depositing deltas of silt on the terrace below. When I pointed this out to Mr. Simon, and later discussed it with his colleagues and supervisor, Mr. Lennox Diasley in Kingstown, they all agreed that vetiver grass had given them perfect protection for the past 50 years. So why should they replace it? The main reason seems to be that nobody has ever told them that their system of soil conservation is possibly the best in the world today. The vetiver system of soil conservation has served St. Vincent well and is a silent partner in the island's farming production. The people have lived with the grass all their lives; indeed, it has become so commonplace that they do not see it. In other words, they have passed those vegetative barriers every day without appreciating the natural terraces that have formed from soil that would have been lost had it been allowed to wash to the sea. But this "silent sentinel" doing its job 24 hours a day, 365 days of the year, has been protecting St. Vincent for the past 50 years. On top of that, it has cost the country nothing. |

conservation, a means of "drought-proofing" previously vulnerable rainfed areas.

In the late 1980s, Richard Grimshaw set out to see if vetiver might block the loss of soil and moisture in other parts of Asia.

In China in 1988, for example, he managed to get it incorporated into a very large World Bank program (the Red Soils Project) in Jiangxi and Fujian provinces. The Chinese agriculturists were so captivated with the vetiver hedges' promise that they immediately bought up every vetiver plant they could find and planted lines across 300 hectares of steep slopes. Initially, they used the grass mainly to protect the faces of existing terraces, but they also incorporated small trials to protect tea plantings on steep, smooth, unterraced slopes.

Even on these acidic, infertile lands south of the Yangtze, vetiver grew well. As in Fiji and India, it was able to dramatically slow up soil loss and reduce runoff. This especially impressed the Chinese, who have created vast areas of terracing whose maintenance is very expensive (and getting more so every year). Vetiver hedges promised to slash these costs. Soon, China had set up a vetiver information network, a collection of vetiver nurseries, and a series of trials in nine provinces.

China was not the only Far Eastern nation to get involved. In the Philippines in 1988, Grimshaw noticed an eroding catchment on the island of Cebu. Nosing around on a hillside nearby, he spied some vetiver and showed the farmer how to dig it up, break off slips, and plant them in lines across the slope. In central Luzon he persuaded the irrigation authorities to test it on farms in the Pantabangan reservoir area. Within 3 months the catchment was starting to stabilize. Since then, it has withstood heavy rainfall (the area receives at least 2,000 mm in a 4-month rainy season) and has turned into terraces that no longer melt away with every rain. Agriculture had become sustainable there for the first time.

In 1990, thanks largely to Grimshaw's enthusiasm, vetiver programs were initiated in Malaysia, Thailand, Laos, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Nepal. And soon information started filtering in from places beyond Asia.

Vetiver, it turned out, has been and still is widely used in the Caribbean to keep roadsides and farm fields from washing out. Normally, it is not planted in any organized operation; it is just a commonplace method of erosion protection going back at least 50 years and known to almost everyone. In 1988 Greenfield visited the Caribbean nation of St. Vincent, only to find that the people were about to cut out all the vetiver hedges. There was no erosion problem on the island, they said, so there was no need for these strips of rough grass across their slopes!

Beyond all these surprising experiences, the plant itself turned out to be remarkable. The more Greenfield, Grimshaw, and their colleagues

learned about it, the more amazed they were. Some of the features that came to light were indeed hard to believe.

One clump of vetiver remained submerged beneath muddy floodwaters for 45 days and still emerged alive and apparently unscathed. Others withstood fire. In Fiji, for instance, the practice of burning cane trash after the harvest each year does no lasting damage to the rows of vetiver weaving through the fields. In fact, creeping ground fires usually stop dead when they meet a dense wall of the grass in its green state.

Vetiver is immune to many other Third World hazards as well. The crown of the plant occurs slightly below the soil surface so that grazing goats or even trampling cattle do no lasting damage. Moreover, the mature foliage is so tough and coarse that even with all the cattle roaming the Indian countryside, the plant is never destroyed. This is important for an erosion control crop that, if it is to work effectively, must stay in place for years, even in the presence of hordes of hungry animals. On the other hand, if the vetiver plants were cut back during the growing season, the masses of new green shoots that quickly arose could be fed to livestock.

Vetiver also grew roots amazingly fast. In a special glass-fronted box that Greenfield built in New Delhi, the roots reached as deep as 1 m just 2 months after planting, even though it was winter. In 3 months they were more than 2 m deep.

Of added significance was the fact that the roots grew almost straight down. There were few lateral surface roots. This seemed to explain the widespread observation that sugarcane and other crops would grow right up to a vetiver hedge, seemingly without interference and loss of yield.

Above ground the plants also grew rapidly. In certain sites they reached 2 m tall in just a few weeks. On the other hand, they spread only slightly. Indeed, the bases expand so little that in certain parts of India vetiver hedges are legally accepted as property lines. In Nigeria, too, the surveyor general has in the past permitted vetiver as a legal boundary marker.

All this may seem strange, but there is more. Vetiver grows so densely that, at least according to various informants, it can block the spread of weeds, including some of the world's worst creeping grasses: couch, star, kikuyu, and Bermuda. In Zimbabwe, for example, tobacco farmers reportedly plant vetiver around their fields to keep kikuyu grass from creeping in. In Mauritius, sugarcane growers rely on vetiver to prevent Bermuda grass from penetrating their fields from adjacent roadsides.

Some claim that vetiver also blocks the spread of animals. Many in India, for example, say that snakes will not go through a stand of vetiver because, they believe, the sharp-edged leaves cut the snakes' bodies. This probably mistaken belief leads people to walk confidently

where there is a vetiver hedge. In China, a farmer planted vetiver grass around his pond: within six months it had formed an almost impenetrable hedge that not only corralled his ducks but also provided fodder and mulch.

Not the least of these observations was that vetiver can grow in an amazing range of soils. In fact, the plant seemed to thrive so well in adversity that it was hard to find a place where it would not survive. Even in quartz gravel, with little fertility, Greenfield was able to make it grow, after a fashion. And, most impressive to a plant scientist, in Sri Lanka some vetiver grows in bauxite, a material that is toxic to almost every other species of plant. (The farmers there actually used crowbars to plant the vetiver into solid bauxite.)

It can grow in an amazing range of climates as well. Both Fiji and central India lie in the monsoonal tropics, but soon it became clear that vetiver could grow in many other climes. In India, for example, it is found in the rainforests of Kerala, the deserts of Rajasthan, and the frost zones of the Himalaya foothills. (It is even found near Kathmandu in Nepal.) It occurs on some coasts, growing in the direct path of salt spray. All in all, it seemed that vetiver grass could thrive under very wet (more than 3,000 mm) and very dry (less than 300 mm) conditions, and perhaps everything in between.

Vetiver also proved well adapted to temperature. It thrives in Rajasthan, where temperatures reach as high as +46°C, and it survives in Fujian, China, where winter temperatures have reached -9°C. It is certainly surprising that a tropical grass can withstand such cold, but one enthusiast even planted it on a ski slope in Italy, and there, north of Rome, it has (perhaps miraculously) made it through several winters.

With all these discoveries about a species almost unknown to the world, it is not surprising that Greenfield and Grimshaw were enthusiastic. Eventually, through word of mouth and the World Bank's Vetiver Newsletter and its handbook, Vetiver: a Hedge Against Erosion, others also were caught up in the fervor. Indeed, the excitement surrounding vetiver grew so much and the implications of using it seemed so astounding that many outsiders queried the sincerity (not to say sanity) of those who were discussing it with such zeal.

It was the skepticism surrounding the extravagant claims about the plant that led to this report. The World Bank, the U.S. Agency for International Development, and the U.S. Soil Conservation Service asked the National Research Council to evaluate the claims, the practical reality, and the implications behind the vision of John Greenfield and Richard Grimshaw.

The rest of this report highlights our findings and conclusions.