5

The Plant

Vetiver belongs to the same part of the grass family as maize, sorghum, sugarcane, and lemongrass.1 Its botanic name, Vetiveria zizanioides (Linn) Nash, has had a checkered history—at least 11 other names in 4 different genera have been employed in the past. The generic name comes from "vetiver," a Tamil word meaning "root that is dug up." The specific name zizanioides (sometimes misspelled zizanoides ) was given first by the great Swedish taxonomist Carolus Linnaeus in 1771. It means "by the riverside," and reflects the fact that the plant is commonly found along waterways in India.

NATURAL HABITAT

For a plant that grows so well on hillsides, vetiver's natural habitat may seem strange. It grows wild in low, damp sites such as swamps and bogs.

The exact location of its origin is not precisely known. Most botanists conclude that it is native to northern India; some say that it is native around Bombay. However, for all practical purposes, the wild plant inhabits the tropical and subtropical plains throughout northern India, Bangladesh, and Burma.

THE TWO TYPES

It is important to realize that vetiver comes in two types—a crucial point because only one of them is suitable for use around the world. If the wrong one is planted, it may spread and produce problems for farmers.

The two are:

-

A wild type from North India. This is the original undomesticated species. It flowers regularly, sets fertile seed, and is known as a "colonizer." Its rooting tends to be shallow, especially in the damp ground it seems to prefer. If loosed on the world, it might become a weed.

-

A "domesticated" type from South India. This is the vetiver that has existed under cultivation for centuries and is widely distributed throughout the tropics. It is probably a man-made selection from the wild type. It is nonflowering, nonseeding (or at least nonspreading), and must be replicated by vegetative propagation. It is the only safe type to use for erosion control.

It is not easy to differentiate between the two types—especially when their flowers cannot be seen. Over the years, Indian scientists have tried to find distinguishing features. These have included differences in:

-

Stems. The South Indian type is said to have a thicker stem.

-

Roots. The South India type is said to have roots with less branching.

-

Leaves. The South India type apparently possesses wider leaves (1.1 cm vs 0.7 cm, on average).2

-

Oil content. The South India type has a higher oil content and a higher yield of roots.

-

Physical properties. Oil from the wild roots of North India is said to be highly levorotatory (rotates the plane of polarized light to the left), whereas that from the cultivated roots from South India is dextrorotatory (rotates polarized light to the right).

-

Scent. The oils from the two types differ in aroma and volatile ingredients.

Whether these differences are truly diagnostic for the two genotypes is as yet unclear. However, at least one group of researchers consider that the two vetivers represent distinct races or even distinct species. 3 Perhaps a test based on a DNA profile will soon settle the issue.

PHYSIOLOGY

Like its relatives maize, sorghum, and sugarcane, vetiver is among the group of plants that use a specialized photosynthesis. Plants

employing this so-called C4 pathway use carbon dioxide more efficiently than those with the normal (C3 or Calvin cycle) photosynthesis. For one thing, most C4 plants convert carbon dioxide to sugars using less water, which helps them thrive under dry conditions. For another, they continue growing and "fixing" carbon dioxide at high rates even with their stomata partially closed. Since stomata close when a plant is stressed (by drought or salinity, for instance), C4 plants tend to perform better than most plants under adversity.

The vetiver plant is insensitive to photoperiod and grows and flowers year-round where temperatures permit. It is best suited to open sunlight and will not establish easily under shady conditions. However, once established, plants can survive in deep shade for decades. They tolerate the near darkness under rubber trees and tropical forests, for example.

ARCHITECTURE

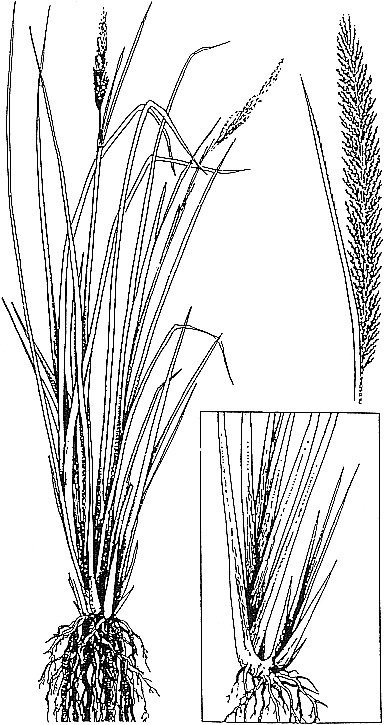

In its general aspect a vetiver plant4 looks like a big, coarse clump grass—not very different from pampas grass, citronella grass, or lemongrass. It can, however, grow to be very tall. Under favorable conditions the erect stems (culms) can reach heights of 3 m.

For purposes of erosion control, vetiver has a number of singular architectural and anatomical features:

-

Habit. The plant has an erect habit and keeps its leaves up off the ground. This seems to be important in allowing the hedge to close up tight, and it also allows crops to be grown next to the plant.

-

Resistance to toppling. Unlike many grasses, vetiver is "bottom heavy." It shows no tendency to fall over (lodge), despite its very tall culms.

-

Strength. The woody and interfolded structures of the stems and leaf bases are extremely strong.

-

Year-round performance. Although vetiver goes dormant during winter months or dry seasons, its stems and leaves stay stiff and firmly attached to the crown. This means that the plant continues stopping soil, even in the off-seasons or (at least for some months) after death.

-

Self-rising ability. As silt builds up behind a vetiver plant, the crown rises to match the new level of the soil surface. The hedge is thus a living barrier that cannot be smothered by a slow rise of sediment. Like dune grasses at the beach, it puts out new roots as dirt builds up around its stems.

-

"Underground networking." Vetiver is a sod-forming grass. Its clumps grow out, and when they intersect with neighboring ones they

-

intertwine and form a sod. It is this that makes the hedges so tight and compact that they can block the movement of soil.

-

Clump integrity. For all practical purposes, vetiver has no running rhizomes or stolons.5 This, too, helps keep the hedge dense and tight. The clumps do not readily die out in the center. Unlike most other clump grasses, even old vetiver plants seldom have empty middles. 6

Crown

The crown of the plant is generally a few centimeters below the surface of the ground. It is a "dome" of dead material, debris, and growing tissue, much of it a tangled knot of rhizomes. These rhizomes are very short—1 cm or less—and are often turned back on themselves. It is apparently for this reason that vetiver stays in clumps and does not spread across the land.

To separate the slips for planting, the often massive crown is cut apart. It is sometimes so huge that it has to be pulled out of the ground with a tractor and cut up with axes. In nurseries, however, young slips are easily separated.

Leaves and Stems

It is, of course, the leaves and stems that are crucial in this living-hedge form of erosion control. Vetiver leaves are somewhat like those of sugarcane, but narrower. Although the blades are soft at the top, the lower portions are firm and hard.

On some vetiver types the leaves have edges sharp enough to cut a person. Actually, this is due to tiny barbs. There is a lot of variability, however: some plants are fiercely barbed, some not. The ones used for oil and erosion control tend to be smooth edged. Topping the plants is an easy way (at least temporarily) to remove the bother of the barbs.

The leaves apparently have fewer stomata than one would expect, which perhaps helps account for the plant withstanding drought so well.

It is the stems that provide the "backbone" of the erosion-control barrier. Strong, hard, and lignified (as in bamboo), they act like a wooden palisade across the hill slope. The strongest are those that bear the inflorescence. These stiff and canelike culms have prominent nodes that can form roots, which is one of the ways the plant uses to rise when it gets buried. (It also moves up by growing from rhizomes on the crown.)

Throughout their length, the culms are usually sheathed with a

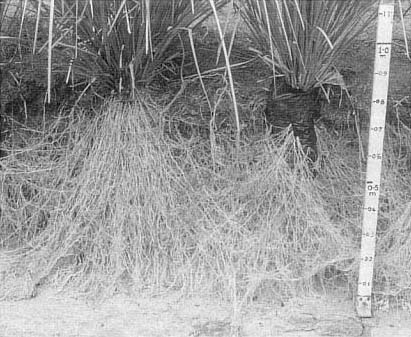

Even experienced plant scientists are surprised by the shape and massiveness of vetiver's roots. The thin and lacy roots grow downwards rather than sideways, and form something like a curtain hanging in the soil. When two plants are side by side, their roots interlock into an underground network. This combination of features anchors a hedge so firmly that even the strongest floods can seldom undermine it or wash it out. Moreover, the roots fall away at a steep angle, and this conical form perhaps explains why vetiver appears not to affect nearby crops. (P.K. Yoon)

leaflike husk. This possibly shields them from stresses—salinity, desiccation, herbicides, or pestilence, for example.

Flowers

The flower (inflorescence) and seedhead are very large: up to 1.5 m long. Both are brown or purple in color. The flower's male and female parts are separated. As in maize, florets in the upper section are male and produce pollen; in vetiver, however, those below are hermaphrodite (both male and female).

Roots

Perhaps most basic to this plant's erosion-fighting ability is its huge spongy mass of roots. These are not only numerous, strong, and fibrous, they tap into soil moisture far below the reach of most crops.

They have been measured at depths below 3 m and can keep the plant alive long after most surrounding vegetation has succumbed to drought.

The massive, deep "ground anchor" also means that even heavy downpours cannot undermine the plant or wash it out. Moreover, because the roots angle steeply downwards, farmers can plow and grow their crops close to the line of grass, so that little cropland is lost when the hedges are in place.

The roots can grow extremely fast. Slips planted in Malaysia produced roots 60 cm deep in just 3 weeks.7

FERTILITY

One of vetiver's great benefits, of course, is that once it is planted it stays in place. It is therefore not pestiferous and seldom spreads into neighboring land.

Actually, though, seeds are often seen on the plant. Why they fail to produce lots of seedlings is not known. Perhaps they are sterile. 8 Perhaps they are fertile but the conditions for germination are seldom present. Or perhaps people just haven't looked hard enough.

Under certain conditions some seeds are indeed fertile. These conditions seem to be most commonly found in tropical swamps. There, in the heat and damp, little vetivers spring up vigorously all around the mother plant.

ECOLOGY

Vetiver is an "ecological-climax" species. It outlasts its neighbors and seems to survive for decades while (at least under normal conditions) showing little or no aggressiveness or colonizing ability.

VETIVER OIL

The oil emits a sweet and pleasant odor. It is used particularly in heavy oriental fragrances. Although primarily employed as a scent, it is so slow to evaporate from the skin that it is also used as a fixative that keeps more volatile oils from evaporating too fast. Because it does not decompose in alkaline medium, vetiver oil is especially good for

|

Vetiver Oil The oil in vetiver roots has a pleasant aroma. The perfumery industry describes it as "heavy," "woody," or "earthy" in character. It is obtained by steam distilling the roots and is used in fine fragrances and in soaps, lotions, deodorants, and other cosmetics. Occasionally its scent dominates a perfume, but more often it provides the foundation on which other scents are superimposed. Haiti, Indonesia (actually only Java), and Réunion (a French island colony in the Indian Ocean) produce most of the world's vetiver oil. China, Brazil, and occasionally other nations produce smaller quantities. Réunion produces the best oil, but Haiti and Indonesia produce the most. Haitian oil is distinctly better than Indonesian and not far behind the Réunion oil (known in the trade as "Bourbon vetiver") in quality. Although reliable statistics are unavailable, world production of vetiver oil is currently about 250 tons a year. Annual consumption is estimated to be:

It seems unlikely that demand will increase beyond these figures, even to match population growth. In recent decades, the international perfumery industry has generally decreased its use in new products. This decision was taken primarily because Haiti manipulates the price of its oil, Indonesia's oil is indifferent and variable in quality, and Bourbon oil is expensive. A completely synthetic vetiver oil cannot be manufactured at a realistic price, but alternative materials such as cedarwood oil can be substituted. For these reasons, world vetiver oil consumption is likely to remain roughly at current levels. Also, some countries have given up producing vetiver oil. For example, Guatemala, which was once an exporter, no longer produces any (even for local use), and Angola (until the early 1970s a regular supplier to the international market) has given up as well. Adapted from S.R.J. Robbins, 1982 |

|

Some Ingredients in Vetiver Oil  American Vetiver Oil The United States is not known as a vetiver oil producer, but as this book was about to be printed we learned that Texas farmers Gueric and Victor Boucard are perhaps the most advanced vetiver growers of all. Since 1972, the Boucards and their late father have been designing implements to plant, harvest, and process vetiver for its oil. These days the Boucards grow the crop on as much as 40 hectares (depending on market prices). All the necessary steps—from large-scale nursery operations to digging to roots—are mechanized. (A modified rock-picker has proved ideal for tearing up the roots.) To us, the surprising thing is that the grass survives in this far-from-tropical location (nearly 30°N latitude and above 500 m). However, Gueric Boucard indicates that this is no problem: "I just cut them off near the ground each fall," he says, "and they have survived temperatures down to -7°C winter after winter, and one cold snap below -12°C for several hours." |

scenting soaps. In at least one country it also serves as a flavoring, primarily to embellish canned asparagus or sherbets.

As already noted, the dried roots are used in India to prepare the traditional "khus-khus" screens. When moistened, these both cool and scent the air passing through, and they are believed to protect people against insect pests as well.

The oil occurs primarily in the roots, but traces of it in the foliage may nonetheless account for the plant's inherent resistance to pests and diseases. The oil is known to repel insects, for example. People in India and elsewhere have long placed vetiver root among their clothes to keep insects away. There seems to be validity in this. In experiments, vetiver root has protected clothes from moths, heads from lice, and bedding from bedbugs. The oil repels flies and cockroaches as well and may make a useful ingredient in insect repellents.

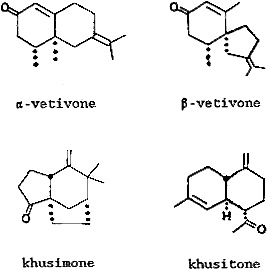

The oil is extremely complex, containing more than 60 compounds. In the main, these are bicyclic and tricyclic sesquiterpenes—hydrocarbons, alcohols, and carboxylic acids. Those that repel insects are minor constituents, including α-vetivone, β-vetivone, khusimone, and khusitone (see illustration, previous page).

ENVIRONMENTAL LIMITS

As noted previously, the plant's environmental limits are unknown. They are, however, surprisingly broad.

As far as moisture is concerned, an established vetiver plant can grow in sites where annual rainfall is perhaps as little as 200 mm. At the other extreme, it also shows tremendous growth where annual rainfall is 3,000 mm. And in Sri Lanka it grows where rainfall is as much as 5,000 mm.

As far as temperature is concerned, this tropical species can take any amount of heat but cannot be counted on to survive subfreezing conditions. For example, plants in Georgia (USA) survived when soil temperatures reached -10°C without apparent damage but died when soil temperatures reached -15°C.

DISEASES

Vetiver is remarkably free of disease.9 However, Fusarium (the most widespread cause of rotting in fruits and vegetables) reportedly attacks it, notably during rains.10

Perhaps of greater import is the leaf blight caused by Curvularia trifolii. This disease of clover and other crops may attack vetiver also during the rainy season. Malaysian researchers recommend that growers top the plants (at a height of 20–30 cm) to remove any infected foliage. Copper-based fungicides such as Bordeaux mixture also control this blight.

In Malaysia, a detailed investigation of vetiver has located yet more fungal species.11 These had little effect on the plant itself, but they might eventually prove troublesome in crops grown near vetiver hedges. They include the following species:

-

Curvularia lunata (causes leaf spot in oil palm)

-

C. maculans (causes leaf spot in oil palm)

-

Helminthosporium halodes (causes leaf spot in oil palm)

-

H. incurvatum (causes leaf spot in coconut)

-

H. maydis (causes leaf blight in maize)

-

H. rostratum (causes leaf disease in oil palm)

-

H. sacchari (causes eye spot in sugarcane)

-

H. stenospilum (causes brown stripe in sugarcane)

-

H. turcicum (causes leaf blight in maize).

PESTS

Termites sometimes attack vetiver, but seemingly only in arid regions. Except where the termite mound covers the whole plant, only dead stems in the center of stressed plants are affected. Normally no treatments are required.

In at least one location in India, grubs of a beetle (Phyllophaga serrata) have been found infesting vetiver roots.12

Perhaps the most serious pest threat comes from stem borers (Chilo spp.). These were found in vetiver hedges in Jianxi Province, China, in 1989. In Asia and Africa, some of these moth larvae are severe cereal pests (for example, the rice borer of Southeast Asia and the sorghum borer of Africa).

Until this potential problem is better understood, vetiver plantings should be carefully monitored in areas where stem borers are a problem. This is both to protect the hedges and to prevent them from providing safe havens for these crop pests. A severe pruning seems to keep the larva from "overwintering" in the vetiver stems and a timely fire might also be beneficial.13

Root-Knot Nematodes

Vetiver has outstanding resistance to root-knot nematodes. In trials in Brazil it proved "immune" to Meloidogyne incognita race 1 and Meloidogyne javanica.14

PROPAGATION

Currently, vetiver is propagated mainly by root division or slips. These are usually ripped off the main clump and jabbed into the ground like seedlings. Although the growth may be tardy initially, the plants develop quickly once roots are established. Growth of 5 cm per day for more than 60 days has been measured in Malaysia. Even where such rapid growth is not possible, the plants often reach 2 m in height after just a few months.

It is easy to build up large numbers of vetiver slips. The plant responds to fertilizer and irrigation with massive tillering, and each tiller can be broken off and planted. It is important to put the nurseries on light soil so the plants can be pulled up easily.

Planting slips is not the only way to propagate vetiver. Other vegetative methods follow:

-

Tissue culture. Micropropagation of vetiver began in the late 1980s.15

-

Ratooning. Like its relative sugarcane, the plant can be cut to the ground and left to resprout.

-

Lateral budding. Researchers in South Africa are having success growing vetiver "eyes" (intercalary buds on surface of crown) in seedling dishes.16

-

Culms. As noted in chapter 2, young stems easily form new roots. This can be an effective means for propagating the plant. Laying the culms on moist sand and keeping them under mist results in the rapid formation of shoots at each node.17 This is an effective way to propagate new plants from hedge trimmings.

-

Cuttings. One Chinese farmer has successfully grown vetiver from stem cuttings. The cuttings, each with two nodes, are planted at a 60° angle and then treated with a rooting hormone—in this case, IAA

-

(indole acetic acid). He achieved 70 percent survival. An interesting point was that the original stems were cut in December, buried in the ground over the winter, and the cuttings were made in early spring and planted in April.

Hedge Formation

Normally, hedges are established by jabbing slips into holes or furrows. They can be planted with bullock, trowel, or dibbling stick. In principle, at least, the techniques and machines developed for planting tree or vegetable seedlings could also be employed.

To establish the hedge quickly, large clumps can be planted close together (10 cm). On the other hand, when planting material is scarce, slips can be spaced as far apart as 20 cm. In this case, the hedge will take longer to close.

Prolonged moisture is highly beneficial for the quick establishment of the hedge. For best results, fresh and well-rooted slips, preferably containing a young stem, should be planted early in the wet season (after the point when there is a good chance the rains will continue). In drier areas it is helpful to plant them in shallow ditches that collect runoff water. For the most rapid establishment of vetiver lines, weeding should be done regularly until the young plants take over. Clipping the young plants back stimulates early tillering and makes the hedge close up faster.

Management

Usually, little management is needed once the hedge is established. However, cutting the tops of the plants produces more tillering and therefore a denser hedge.

CONTROLLING VETIVER

Vetiver is a survivor. It is difficult to kill by fire, grazing, drought, or other natural force. However, if necessary, it can be eliminated by slicing off the crown. Because the crown is close to the surface, it can be cut off fairly easily with a shovel or tractor blade. Also, although the plant is resistant to most herbicides, it succumbs to those based on glyphosate.