Appendix A

Great Challenges, Great Opportunities

This appendix highlights some environmental horrors and points to the role vetiver might play in alleviating them.1 The examples are presented to stimulate exploratory trials in those parts of the world where such devastating problems exist. Whether vetiver will work in sites like these is far from certain. In some, the plant will meet its greatest difficulties in just surviving. In a few, it may survive but fail to be effective. Nonetheless, it is a testimony to the potential inherent in vetiver that a single species could even be considered for such an array of challenging situations. Also, it is a testimony to the potential inherent in their green lines of grass that solutions to so many seemingly intractable problems can even be envisioned. Where vetiver fails, alternative species that make dense hedges should be sought.

In popular perception, the ultimate erosion site is one in which all the soil is stripped away and only bedrock is left. In reality, however, some form of "subsoil" normally remains (as in this case in Indonesia). The site may have lost all of what scientists call "weathered soil"—the upper part that had been exposed to air, rain, heat, cold, plant life, microbes, and the other natural forces that create a friable foundation for vegetation to grow in. But in most cases, something approximating soil remains.

This so-called subsoil is uninfluenced by biological activity, and few plants can grow in it. Vetiver is one of the few that can, at least in some cases. In fact, the grass may be the long-dreamed-of tool for getting degraded, tropical, lateritic soils (oxisols) into productive use. Even a tenuous hold on just some of these subsoils could give important benefits. Vetiver hedges backed up with other plants, especially legumes, might become a soil-recovery tool of exceptional value in these days when people fear that the world is running out of farmland. (Photo: Hugh Popenoe)

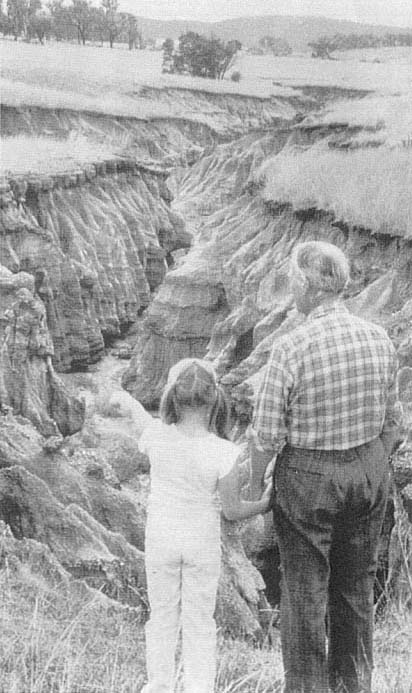

Opposite: The deep soil here could be producing a lot of food, forage, or perhaps forests, but instead is being inexorably lost. Ideally, runoff pouring from the land behind should be deflected and dispersed far above this site. (That might well be done using vetiver hedges.) However, it is likely that the landowner will opt instead to merely try to stop this gully from worsening. (Indeed, it is a measure of the expense or ineffectiveness of the better known techniques that erosion has been allowed to progress so far on this valuable property.)

For such a task, vetiver seems very suitable. Starting at the head of the gully, lines of the grass can be planted from left to right. The lines should be spaced several meters apart and each should begin at a level several meters above the bottom on one side, run across the gully, and up to the same level on the other side. Once established, these grassy barriers will check the force of the rushing runoff and stop the silt from leaving the site. Through the years, a series of stable terraces will form, eventually resulting in an almost rounded depression that can be grassed and then grazed or safely planted with trees.

This particular location in rural Australia is not in vetiver's prime geographic zone; however, countless similar scenes can be found throughout the hot regions where vetiver thrives. (Photo: Australian Academy of Science)

Overleaf: When watersheds are degraded to the point where they no longer absorb torrential rains, property can be destroyed and lives lost even at a great distance. With deforestation laying bare more and more of the world's sloping lands, flooding is an increasing hazard to everyone. Rushing runoff can pour into the lowlands with a power beyond stopping even in city streets.

Protecting vast watersheds with thousands of vetiver rows might well seem nigh on impossible, both logistically and financially. However, compared to conventional berms, bunds, and terracing, such grassy dams may be practical on a wide scale. Massive efforts would certainly be required, but this could well pay off many times over if it prevents a single incident like the one shown here in Hong Kong. Cities (or maybe insurance companies) might well find it in their interest to stimulate the necessary vetiver plantings on the faraway hills. (Photo: Hong Kong Government Information Services)

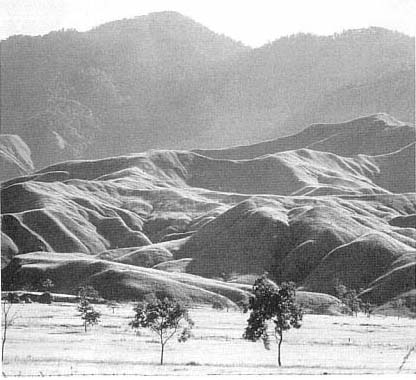

In most parts of the tropics, deforested lands end up covered in weedy grasses such as the Imperata cylindrica (known variously as imperata, lalang, alangalang, cogon, and other names) shown here on the lower slopes. Recovering such wastelands involves two challenges: fighting the vigorous weed and ensuring that erosion will not take over once the vegetation cover is disturbed.

For decades, people have searched for ways to recoup lands like these. Vetiver could be the key. It both competes with aggressive grasses and safeguards against erosion. In the case shown, rows of vetive along the contours could be a first step toward reclaiming the unused lower slopes. Such hedges could then make it worth a farmer's time and effort to grow either crops or trees between the rows.

Should this speculation prove out in practice, the benefits would be immense. Restoring such slopes would give millions of the poor and destitute both land and a chance for a favorable future. It might even slow down (or perhaps stop) their destruction of the forests on the higher hills.

This picture was taken in Papua New Guinea, but grassy unused lands like this can be seen on all sides throughout most of the tropics. In Asia alone, imperata is keeping more than 50 million hectares out of useful production.2 (Photo: Noel Vietmeyer)

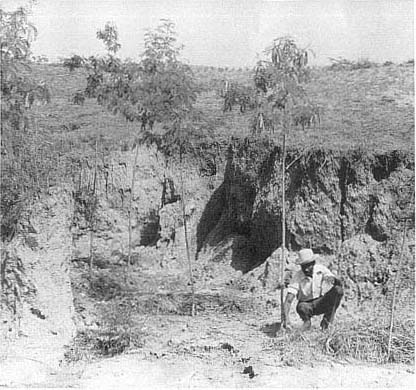

Although the idea that trees stop erosion is almost universally accepted, it is more accurate to say that forests are what really do the job. As can be seen here (in Haiti), trees by themselves can do little unless the soil around them is somehow protected. A carpet of ground-level vegetation or the litter of fallen leaves is what normally saves the site from losing its surface. Lacking such support, the trees here are obviously very vulnerable. The collapsing bank behind and probable washouts in front have doomed even these resilient leucaenas.

For much of tropical forestry, vetiver should be an ideal adjunct. Here, for instance, the young trees could be easily supported by just a few short vetiver hedges behind and perhaps one in front. (Ideally, the hedges should have been put in before the trees were planted.) Not only would the soil then be stabilized, the trees would almost certainly grow faster and better because of the moisture, leaf-litter, and silt collected behind the hedgerows. Vetiver, moreover, will protect the site whenever the soil might be reexposed—for example, if the trees are ever defoliated by hurricanes, clear-cutting, pests, or people desperate for forage or firewood. (CARE photo by Dan Stephens)

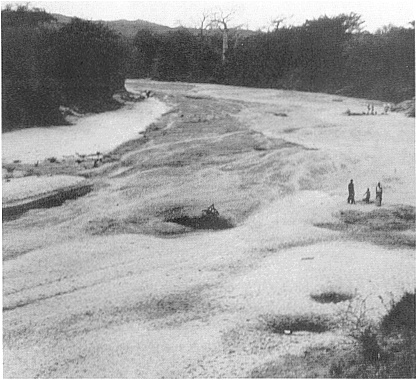

People normally think of erosion in terms of the loss of land, but the soil is not actually lost—the wind or water just moves it to a different location. Often this process destroys as much in the new location as in the old. Throughout the world, facilities worth billions of dollars are annually being rendered useless by a deadly burden of unwanted dirt. Silt is inexorably ruining rivers, reservoirs, estuaries, ports, coral reefs, wetlands, waterways, and irrigation schemes in virtually every country that has them. This useless, soil-filled reservoir in Haiti is just one example.

Vetiver plantings in the watersheds, which may be hundreds of kilometers away, offers a chance to protect such sites. It is cheap, easy, effective, almost maintenance free, and compatible with most farming and forestry activities. With vetiver, remote watersheds no longer need be left to spew out silt.

Governments, utility companies, multinational lending organizations, and others whose interest lies in saving public works from systematic ruin by siltation should test out vetiver rapidly. The economic value inherent in extending the lifetimes of water supplies, hydroelectric generators, drainage facilities, flood-control operations, storm-water over-flows, low-lying highways, and other such fundamentals of national infrastructure could be enormous. (Photo: W. Hugh Bollinger)

All over the world, millions of trees are threatened not by people but by erosion. Globally speaking, soil loss probably poses a bigger threat than loggers. In an era when trees are increasingly important to the health of the earth, tree protection should be as valued as tree planting. Where erosion is the enemy, vetiver could be vital.

The grass could save this particular tree in Yatenga Province, Burkina Faso. It would likely rejuvenate the whole site. Long hedges planted roughly across the prevailing gullies would slow the water flow and halt the loss of soil. Within one or two rainy seasons the gullies would be gone. Moreover, the dense hedges would likely benefit the tree by increasing soil moisture. Indeed, local people might voluntarily plant more trees or perhaps crops on this now all-but-unused site because the heartbreak of washouts and undermined plants would have been removed. (Photo: ©Mark Edwards/Still Pictures)

Roads commonly spawn severe erosion. The smooth, flat surface collects water and cascades it over the banks, washing out the slopes below. Slopes above the road are also erosion prone, especially as they are often extremely steep. Embankments freshly cut out of hillsides or built up from fill are particularly vulnerable. The damage can be immense—to the roads, to the neighbors, and to the environment in general.

In a few tropical countries, engineers and maintenance crews already employ vetiver to stabilize roadsides. Many more could take up the practice. Normally, the benefits are realized only over the long term, but in Malaysia nursery-grown vetivers have been planted side-by-side to give "instant" protection.

And roads are not the only man-made structures that induce costly soil losses. Parking lots, airfields, driveways, irrigation pipes, bridge abutments, posts, pylons, walls, as well as construction sites are all prime erosion incubators. For these and many others, vetiver could be a cheap and easy answer. It can survive in many disturbed subsoils. It can take the hazards of humans preoccupied with work. Even an occasional errant vehicle does it no lasting harm.

The picture here shows a logging road in the Cameroon. Remote dirt roads like this seem especially suitable for vetiver; conventional techniques are just too expensive to contemplate. (Photo: WWF/Claude Martin)

The effort required to move dirt for erosion control is enormous, and the results are often less than satisfactory. On steep slopes in high-rainfall areas, for instance, runoff water piles up in ditches like this one until it finds a weak point to break through. Once that happens the soil loss can be greater than if the slope had been left untouched: the cascading water creates a sort of domino effect that breaches terrace after terrace right down the slope. All in all, physical barriers are inherently unstable in tropical areas where annual rainfall is often measured in thousands of millimeters.

Moreover, even gentle rains wash soil down into the ditches, filling them in and erasing all the hard work. (In the case shown, the back wall is steeper than the soil's natural angle of repose and is thus highly susceptible to collapse.)

It seems probable that in thousands of sites like this one in Kenya vetiver hedges can be installed for a mere fraction of the normal expense and effort. Planting hedges across the slopes requires no movement of soil. At the very least, vetiver could be employed to strengthen this ditch. The front face could be reinforced and protected and the back wall might be planted with vetiver rows to slow down the dirt that will inevitably return. (Photo: FAO)

Although enormous effort is required to build terraces, it is all wasted unless the site is continuously maintained. In the tropics, thousands of terraces like these in Ethiopia have failed, degraded, or even washed away when they were neglected. Left to themselves, terraces can actually promote erosion, and maintaining them is becoming harder and harder. Not only it is ever more expensive, but finding people to do the tedious and backbreaking work is increasingly difficult (especially with the children off at school). Under these conditions the terraces decline, the erosion accelerates, and the farm yields decrease.

Vetiver has excellent promise for protecting the eroding faces of terraces throughout the warmer parts of the world. Moreover, it can add new flexibility. With the tough grass protecting the lip, terraces can be "forward sloping"—a style that is less susceptible to washouts and takes up less land than the current (backward-sloping) kind. The grass-covered face guards against gullying whenever the terraces are overtopped. (Photo: A. Rapp)

Watersides are major sources of both soil erosion and water pollution. Hundreds of thousands of rivers, streams, lakes, wetlands, canals, conduits, culverts, ditches, fish ponds, farm ponds, effluent ponds, "tanks," drains, swales, swamps, settling basins, reservoirs, and other kinds of waterways are affected every day. Water biting into the bottom of banks like these along the Amazon inevitably tumbles soil in. Yet waterside erosion is difficult to overcome—especially in rural Third World sites, where concrete and other engineered structures are impractical.

Vetiver, however, is at home on the interface between land and water. It is one of the few terrestrial plants able to take wet conditions, even total immersion. For this reason alone, it might become outstandingly useful.

So far this possible utility has hardly ever been tested. Although certain fish ponds in Malaysia and China have been hedged in with the grass, and although riverbank rows of vetiver are being used to save a small rural airport in Nepal, the widespread potential of erosion-control hedges along the banks of waterways is not widely appreciated. In this concept, however, there could be myriad possibilities for protecting waterways of all kinds. (Photo: © Mark Edwards/Still Pictures)

Among vetiver's many strange qualities, the ability to withstand both dryness and flooding stands out as something that might be put to practical use. Could this plant be employed in helping treat wastewater in the tropics? It certainly seems possible that grass hedges could capture sediments and thereby clean wastewater before it is released into the environment.

In various parts of the world, ponds and marshes are starting to be used to purify wastes from industry, cities, and agriculture. Scientists in both Europe and North America, for instance, are finding that an artificial wetland works at least as well as a conventional treatment facility. They employ reeds, bulrushes, and other aquatic plants. In the hot parts of the world (such as this site in Mexico) vetiver might be a superb substitute or complement.

Artificial wetlands might also be used to filter more than just sewage. Other possibilities are: process water used in industry, animal-waste runoff, pesticides leaching off farmlands, and storm water. The last is of particular concern these days. Rains wash motor oil, tar, animal droppings, and battery fluids from city streets and sluice them down what are known as "storm-water drains." A few cities are experimenting with filtering such chemical cocktails using man-made marshes. New Orleans, for example, aims to cut its storm-water pollution by half this way. (Photo: ©Mark Edwards/Still Pictures)

A common practice, recommended by authorities throughout the world, is the gully check. This is typically a "dam" of masonry, rocks, sandbags, logs, or brushwood. Thousands are installed in isolated catchments in every country.

These structures can cost a lot to build, and their installation often takes a huge amount of effort. Yet they are always temporary. Gully checks inevitably silt up, breach, or get bypassed. Typically, runoff flows over or around the barrier, digging holes and ultimately collapsing the whole structure.

Vetiver seems to offer a better solution. Unlike these "dead dams," a vetiver hedge is alive and self-adjusting. It grows, it bends, it rises up, and it anchors itself deeply in the soil. Moreover, it spreads the runoff out, and any excessive flow runs harmlessly over it and down the grass-covered face of a naturally formed terrace.

This location in the Colombian highlands should be ideal vetiver country. (Photo: D. Henrichsen)

Wherever coconuts are processed, mountains of residue remain. The husk surrounding the nut is almost impervious to decay, and although the longer fibers (known as coir) may be woven into mats and other products, the shorter ones pile up in huge, unsightly heaps. Sri Lanka, shown above, has an estimated 35 million tons of this so-called "coir dust" lying unused.

Now, however, there seems to be a breakthrough. Almost a decade's research has shown that coir dust is one of the world's best mediums for cultivating plants. It absorbs and holds moisture, it retains a light and open structure, and it resists decay and fungal diseases. European plant nurseries and flower growers are starting to use it in place of peat or sphagnum moss.

Even more potential might be found in using coir dust for rejuvenating worn-out soils in the tropics. Mixed with manure, it creates an almost perfect medium for high crop yields.

Probably this simple idea has not previously been implemented because tropical rains wash coir compost away too readily. Here is where vetiver comes in. Hedges of the dense grass could be just the ticket for holding the highly movable soil amendment in place. In the uplands of Sri Lanka, this combination is already showing promise. Vetiver hedges are holding the man-made medium in place, and crops are being grown in coir dust and manure on a barren area that is almost down to bedrock. (Photo: Lee St. Lawrence)

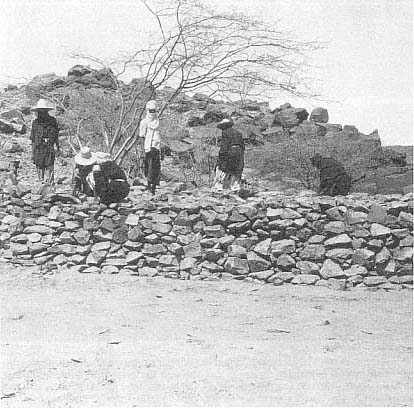

Even in deserts, rain often falls in torrents. In fact, periodic flooding is a paradox of many arid lands. However, all too often the soils are unable to absorb the deluge; water of immense value rushes away uselessly (and sometimes destructively) down wadis. To capture the bounty of desert downpours has been the aim of what is generally known as "water harvesting." In one popular approach barriers are erected across the wadis, gulches, gorges, and other natural funnels of flash flooding.

Rock walls, like those being erected here in West Africa, are a common form of barrier. Grassy hedges might be much better. They would be easier to install, unlikely to wash out, and would grow taller as silt builds up behind—a feat that rocks haven't learned yet. Moreover, vetiver is more than just a barrier. It is also a trickle filter that keeps excessive flows spread out so they can sink evenly into the land. All in all, a series of hedges could rob gully-washers of their force and keep the water (and the silt) right where it is most needed. Even in extremely dry zones like this one near Agades in Niger, moisture deep in the wadi bottom should keep the hedges alive through even the driest seasons. (Photo: Oxfam-America)

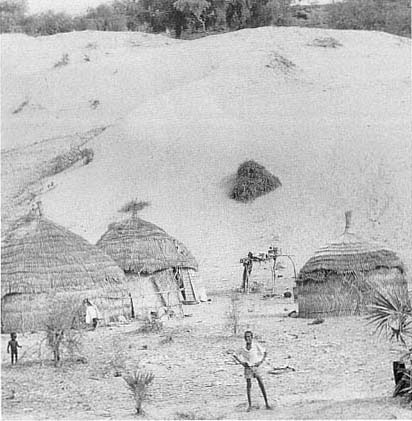

Vetiver may be a "safety belt" that can help protect sites endangered by desertification. Although apparently native to swamps, the plant shows remarkable ability to survive in dry lands as well. A site like the one shown is obviously a challenge, but vetiver hedges might prove capable of holding back the sand, stabilizing the dune, and saving the houses from destruction. Moisture builds up in sand dunes, and this grass, with its vast and deep root system, should tap into it well.

Assuming vetiver can survive in this dune near Niamey in Niger, hedges along the back side will slow and maybe halt the sand's forward progress. Rows across the face would also help. This simple technique certainly should be within the means (both financial and technical) of these homeowners, who in most remote and impoverished locations are the only ones likely to do anything. The villagers themselves should be enthusiastic cooperators—seeing in this natural and easy-to-understand method not only a chance to save their homes and fields but also a way to get back to producing trees or crops on the sandy slopes. (Photo: © Mark Edwards/Still Pictures)

To tame moving sands in drought-ridden regions, the authorities sometimes set up massive gridlike networks of palm fronds. Each frond is laboriously cut from a palm and dug into the dunes. If vetiver can survive here, it would probably be more effective. This deeply rooted plant is unlikely to be blown over. It can rise up to match sand accumulations and is thus unlikely to be buried. It also resists grazing, even by goats. This grass, which can be taller than these fronds being planted in Tunisia, might prove to be practical for protecting foot tracks, roads, railways, canals, villages, houses, forests, and other facilities from blowing sand.

Further, in areas such as West Africa, vetiver's strong but resilient foliage should make an excellent windbreak. Farmers might find it especially valuable because the winds rise with the onset of the rains, and fine sand blowing across the surface of the land often buries crops before their seedlings can even get a grip on life.

Of course, the climate in this area is very different from that where vetiver is best known. Despite the moisture in the dunes, the plant is quite likely to fail. However, a vetiver relative (Vetiveria nigritana) is native to Africa. It, as well as other tall native grasses, may prove better. (Photo: FAO)