B5

Use of Antiprogestins Before 63 days of Amenorrhea

MARC BYGDEMAN, M.D.

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Karolinska Hospital, Stockholm

INTRODUCTION

Progesterone plays a central role in the establishment and maintenance of pregnancy. It is secreted by the corpus luteum during the second part of the menstrual cycle and during early pregnancy, and by the placenta after the luteal placental shift, which occurs between six and eight weeks of pregnancy. It is essential for the nidation of the conceptus and is thought to inhibit myometrial contractility, thereby ensuring that the uterus is kept in a quiescent state throughout pregnancy.

EFFECT OF MIFEPRISTONE DURING EARLY PREGNANCY

The mechanism through which mifepristone terminates early pregnancy has not been fully elucidated. Blockage of the progesterone receptor by treatment with mifepristone leads to ultrastructural changes in the endothelium of decidual capillaries, vascular damage, bleeding, decidual necrosis, detachment, and ultimately, expulsion of the products of conception (see references in Van Look and Bygdeman, 1989). It has been suggested that the first step in this series of events is an increased local concentration of prostaglandins, since mifepristone stimulates the synthesis of prostaglandin by glandular cells of the early human decidua (Smith and Kelly, 1987).

Of great importance for the clinical use of mifepristone as an abortifacient is the effect of the compound on uterine contractility. During early pregnancy the uterus is inactive, probably due to the

inhibitory effect of progesterone. Treatment with mifepristone changes the inactive uterus to an active one. The time interval between the start of mifepristone treatment and the appearance of uterine contractions is 24 to 36 hours. Simultaneous with increased contractility, the sensitivity to prostaglandin increases about five times (Swahn and Bygdeman, 1988). These data created the scientific background for combining mifepristone and a low dose of prostaglandin for termination of early pregnancy.

Mifepristone also has a ripening effect on the cervix and causes dilatation of the cervical canal (Rådestad et al., 1990; WHO, 1990). These effects do not seem to be mediated through a stimulation of endogenous prostaglandin production because they are not blocked by simultaneous treatment with prostaglandin biosynthesis inhibitors (Rådestad and Bygdeman, 1992). It is possible, however, that the antiprogestin acts by inhibiting or changing prostaglandin metabolism.

TERMINATION OF EARLY PREGNANCY

Mifepristone Alone

Clinical evidence that it was possible to interrupt early human pregnancy with mifepristone was first provided by Hermann et al. (1982) and was confirmed shortly afterwards in a dose-finding study conducted under the auspices of the World Health Organization (Kovacs et al., 1984). Although carried out in a relatively small number of women, these two studies permitted several tentative conclusions that were proven in subsequent trials. Undoubtedly, the most disconcerting findings were the relatively low efficacy, 73 percent and 61 percent, respectively, and the absence of a clear dose-response relationship. Efforts to improve the therapeutic efficacy were made by various investigators and focused on changing the daily dose and the duration of treatment (for references, see Van Look and Bygdeman, 1989). From these studies, two conclusions could be drawn. Firstly, the frequency of complete abortion decreased with advancing pregnancy, and secondly, there was no relationship between the success rate and the treatment regimen employed for women at the same stage of gestation. For pregnancies up to eight weeks the frequency of complete abortion was generally between 60 percent and 70 percent. A somewhat higher success rate could be achieved if treatment was given within the first 10 to 14 days after the missed menstrual period. For example, Couzinet et al. (1986) reported a complete abortion rate of 85 percent following treatment with up to 800 mg mifepristone for 2 to 4 days in women who were within 10 days of missed menses.

TABLE B5.1 Termination of Early Pregnancy by 600 mg Mifepristone and Vaginal Administration of 1.0 mg Gemeprost or 0.25 mg Sulprostone Intramuscularly

|

|

French Multicenter Study (<49 days) |

U.K. Multicenter Study (<63 days) |

|

|

|

Gemeprost (%) |

Sulprostone (%) |

Gemeprost (%) |

|

Complete abortion |

96.5 |

95.4 |

94.0 |

|

Incomplete abortion |

2.3 |

2.8 |

5.0a |

|

Ongoing pregnancy |

0.4 |

0.6 |

|

|

Hemostatic surgical procedure |

0.8 |

0.4 |

1.0 |

|

a In the United Kingdom study, separate figures for incomplete abortion and ongoing pregnancy are not given. SOURCE: U.K. Multicentre Trial (1990); Ulmann et al. (1992). |

|||

Mifepristone in Combination with Prostaglandin

The outcome of treatment is quite different if mifepristone is combined with prostaglandin. In the first study with the combined therapy, 25 mg mifepristone was given twice daily for three to six days. On the last day, 0.25 mg sulprostone (Schering AG, Berlin, Germany) was injected intramuscularly (Bygdeman and Swahn, 1985). The overall frequency of complete abortion was 94 percent. Success rates between 95 and 100 percent were also reported in similar studies where mifepristone was combined with vaginal administration of 0.5 to 1.0 mg gemeprost May and Baker, Dagenham, U.K., 1990 (Cameron et al., 1986; Dubois et al., 1988).

Today mifepristone is available for routine clinical use in France, Great Britain, and Sweden. The dose schedule recommended by the pharmaceutical company (Roussel-Uclaf, Paris) is a single dose of 600 mg mifepristone followed 36 to 48 hours later by 1.0 mg gemeprost. Sulprostone, which was mainly used initially, is no longer available since the intramuscular preparation has been withdrawn from the market. In Sweden and Great Britain the procedure is used through the eighth week of pregnancy (63 days of amenorrhea), whereas in France the upper limit is 49 days of amenorrhea. The clinical outcome of the treatment has been evaluated in two large multicenter clinical studies from France and Great Britain (U.K. Multicentre Trial, 1990; Ulmann, 1992). Mifepristone followed by either vaginal gemeprost or intramuscular injection of sulprostone was shown to be highly effective in terminating early pregnancy. The frequency of complete abortion was around 95 percent, and complete failures in terms of continued pregnancy occurred in about 0.5 percent of the patients (Table B5.1). The clinical events are very similar to those of a spontaneous abortion, with

bleeding and increased uterine contractility. About 50 percent of the patients have started to bleed at the time of prostaglandin treatment, and almost all within four hours thereafter. The mean duration of bleeding in the French study was eight days. In 89.7 percent of the women, bleeding lasted for 12 days or less. In 9 percent of the women the bleeding was described as severe or excessive in the 24 to 48 hours after mifepristone and 4 hours after prostaglandin therapy (U.K. Multicentre Trial, 1990). In 93 percent of the women there was little or no change in the hemoglobin value (up to 1 g/dl) before treatment and seven days after gemeprost administration, while in 1 percent of the patients there was a decrease of 2–4 g/dl. The frequency of hemostatic surgical procedures was between 0.4 and 1.0 in the two studies (Table B5.1).

Uterine pain is also common, especially during the first hours following prostaglandin treatment: 2 percent of the women reported severe pain after mifepristone administration, a frequency that increased to 21 percent two hours after gemeprost administration. The frequency had decreased to 10 percent by four hours in the British study. Clinical signs of infection were rare, or less than 1 percent. Nausea and vomiting were not uncommon during the first hours after prostaglandin therapy.

In the French study, which included more than 16,000 women, serious cardiovascular side effects were reported in four cases after sulprostone injection. They consisted of one acute myocardial infarction attributed to a coronary spasm and marked hypertension in the other three women. Since the drug has been marketed and used in more than 60,000 cases in France, two additional myocardial infarctions have occurred, one of them being fatal. The frequency of severe cardiac complications after sulprostone is thus approximately 1/20,000 cases. As a consequence, smoking more than 10 cigarettes per day, age over 35 years, and any suspicion of cardiovascular disease must be considered relative contraindications to the method. It is noteworthy that so far, no myocardial infarction has occurred when gemeprost has been used, and most likely smaller doses of prostaglandin may still be sufficient and associated with a lower frequency of this type of complication.

As indicated previously, pregnancy might continue in spite of treatment, as occurred in 0.4 to 1.5 percent of clinical trial subjects. Mifepristone is known to cross the placenta (Frydman et al., 1985), and concern has been expressed that the drug may have teratogenic potential. Since surgical uterine evacuation is recommended when the treatment fails, data on infants exposed to mifepristone in utero are rare. However, the information that does exist suggests that the antiprogestin does not cause fetal malformations (Lim et al., 1990; Pom et al., 1991).

TABLE B5.2 Clinical Management of Medical Abortion in Sweden

|

|

Practical Guidelines for Clinical Use of Mifepristone in Combination with Prostaglandin

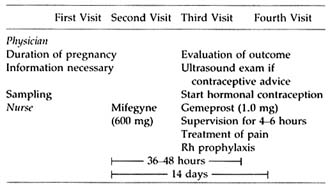

The clinical use of the combination of mifepristone and prostaglandin for termination of pregnancy is more regulated than most other medical procedures: (1) it may be prescribed only in centers registered for pregnancy termination (in Sweden by the National Board of Health and Welfare); (2) distribution of the drug is strictly controlled; and (3) each patient must sign a consent form indicating that she is aware that the method is not risk free and does not have a 100 percent success rate. The treatment includes four visits to the clinic (Table B5.2). The patient is seen by the physician at the initial visit and two weeks after the start of treatment to evaluate the outcome of the therapy. The nurse supervises the intake of mifepristone and the four- to six-hour observation period in the outpatient ward following prostaglandin therapy.

FURTHER DEVELOPMENTS IN MEDICAL TERMINATION OF EARLY PREGNANCY

The ideal combination of mifepristone and prostaglandin remains to be established. Studies in both pregnant and nonpregnant women have shown that the pharmacokinetics of mifepristone are nonlinear and that oral administration of the drug in single doses greater than 100 mg results in serum concentrations that differ only minimally or not at all (for references, see Van Look and Bygdeman, 1989; Puri and Van Look, 1991). Multicenter trials conducted under the auspices of the World Health Organization have shown that the same effectiveness observed with 600 mg can be achieved with either repeated small doses of mifepristone (five doses of 25 mg given at 12-hour intervals) (WHO, 1991) or a single dose of 200 mg (WHO, to be published) if combined

with 1.0 mg gemeprost. It is also likely that the dose of gemeprost may be reduced to 0.5 mg (unpublished observation by author).

Oral administration of the prostaglandin (PG) may be an advantage. The analogue 9-methylene-PGE2 is orally active. When given in combination with mifepristone, this prostaglandin has been reported to terminate 95 percent of early pregnancies (Swahn et al., 1990). Another alternative is misoprostol (G.D. Searle Co., Chicago, Illinois). Misoprostol is licensed for sale in many countries for the treatment of gastric and duodenal ulceration. It is active by mouth, inexpensive, and stable at room temperature. If administered alone during early pregnancy, doses ranging from 200 µg to 600 µg induce significant uterine pressure. However, only 2 of 40 women given misoprostol alone aborted. When misoprostol was administered after mifepristone, there was a significant increase in both amplitude and frequency of uterine contractions, and complete abortion took place in 18 out of 21 women (Norman et al., 1991). Aubeny and Baulieu (1991) treated 100 women who were undergoing legal abortion at gestations of up to 49 days with 600 mg mifepristone followed two days later by 400 µg misoprostol by mouth. Complete abortion was found in 95 women, four women had an incomplete abortion, and in one woman the pregnancy continued despite treatment.

Recently, an extended study from France has been published (Peyron et al., 1993). It includes altogether 25 centers and 895 women with an amenorrhea of less than 50 days. The majority of women (n = 505) were treated with 600 mg mifepristone and 48 hours later, if the abortion had not occurred, 400 µg misopristol (Trial 1). In the remaining 390 women, a second dose of 200 µg misoprostol was given four hours later if the patient had not aborted. This was found necessary in approximately 25 percent of the patients (Trial II). In the first trial with the fixed dose of misoprostol, the success rate (complete abortion) was 96.9 percent. This rate is similar to that previously observed for mifepristone followed by sulprostone or gemeprost. In the second study, in which an extra dose of misoprostol was added if judged necessary, the success rate increased to 98.7 percent. In both trials the majority of women experienced uterine cramps, but only 20 percent required administration of a non-opiate analgesic. This figure is considerably lower than that reported in the United Kingdom multicenter study in 1990 in which 28 percent of women required opiate analgesic and an additional 31 percent non-narcotic analgesia following mifepristone and gemeprost. Although it is well known that the degree of pain and need for analgesic treatment vary considerably, it seems that the replacement of gemeprost by misoprostol will result in decreased pain. However, only a randomized study comparing the two treatment schedules will give definite information.

TABLE B5.3 Termination of Early Pregnancy with 600 mg Mifepristone Followed by 400 µg Misoprostol in Women with an Amenorrhea of Less Than 50 Days (N = 1286)

|

|

Percentage of Patients |

|

Efficacy |

|

|

Complete abortion |

95.4 |

|

Incomplete abortion |

2.8 |

|

Ongoing pregnancy |

1.5 |

|

Hemostatic procedure |

0.3 |

|

Pain |

|

|

Within four hours of misoprostol |

81.5 |

|

Need for analgesia |

19.6 |

|

Narcotic analgesia |

0.1 |

|

SOURCE: Silvestre et al., 1993 |

|

The latest summary of the French experience of the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol for termination of early pregnancy was reported at the recent VIIIth World Congress in Human Reproduction (Silvestre et al., 1993). The report included 1,288 early pregnant women (duration of amenorrhea <50 days) who received 600 mg mifepristone followed two days later by a fixed dose of misoprostol (400 µg). The efficacy of the treatment was evaluated two weeks after the treatment by clinical examination, ß-hCG and or ultrasound scan. The success rate, defined as complete expulsion of the conceptus with no need for additional surgical procedure, was 95.4 percent. Of the remaining patients, 2.8 percent experienced an incomplete abortion, in 1.5 percent the pregnancy continued, and in .3 percent a hemostatic vacuum aspiration was performed (Table B5.3) Expulsion of the conceptus occurred within four days of administration of misoprostol in 59 percent of the women and within 24 hours in 81.5 percent of the women. Almost all women experienced uterine bleeding, the mean duration being nine days, and the mean drop in hemoglobin value was .7 g/d. Blood transfusion was required in only one woman (.1 percent). All these figures are comparable to those reported for the combination of mifepristone and sulprostone or gemeprost (Ulmann et al., 1992). However, also in this study uterine pain seemed less pronounced since the frequency of analgesic treatment was only 19.6 percent and narcotic analgesic was given to only one woman.

If treatment with mifepristone in combination with gemeprost or misoprostol is compared, available data indicate that both treatments are equally effective at least up to 49 days of amenorrhea. After 49 days of amenorrhea, the efficacy of mifepristone in combination with misoprostol seems to decrease significantly (D. Baird, personal communication).

TABLE B5.4 Suggested Differences Between Mifepristone in Combination with Either Gemeprost or Misoprostol

|

|

Mifepristone with: |

|

|

Characteristics |

Gemeprost |

Misoprostol |

|

Efficacy |

|

|

|

<50 days |

— |

— |

|

50–63 days |

+? |

— |

|

Complications |

— |

— |

|

Side effects, mainly uterine pain |

+? |

— |

|

Cost |

++ |

— |

Complications in terms of duration of bleeding, heavy bleeding necessitating treatment, time of expulsion of the conceptus, and pelvic infections seem to be frequent, while uterine pain necessitating treatment seems lower following misoprostol in comparison to gemeprost (Table B5.4).

Once-a-month treatment with mifepristone at the time of menstruation has so far not been found effective. In case of pregnancy the failure rate is around 15 percent (for references, see Van Look and Bygdeman, 1989). To date, the possibility of adding a low dose of prostaglandin has not been evaluated. One obvious reason is that a combination of mifepristone and gemeprost, in about 15 percent of the patients, is so painful that strong analgesic treatment is needed. In a nonpregnant cycle, misoprostol in the doses used (400 µg) has very little effect on uterine contractility, and the effect of prostaglandin is not enhanced by pretreatment with mifepristone (Gemzell et al., 1990). However, if the women were treated with human chorionic gonadotropin to rescue the corpus luteum and create an endocrine situation similar to that in a pregnant cycle, mifepristone followed 48 hours later by 400 µg had a significant effect on uterine contractility (Gemzell et al., 1993). The data indicate that this combined treatment may be effective at the time of menstruation in women exposed to the risk of pregnancy. If the woman does not become pregnant, the degree of uterine stimulation is minor and should not cause any side effects. If she becomes pregnant, the degree of uterine contractility should be sufficient to expel the conceptus.

CONCLUSIONS

The need for a safe, noninvasive method of medical abortion was expressed by the World Health Organization in 1978, and the mifepristone-prostaglandin combination goes a long way towards fulfilling this

concept. Medical abortion using this combination seems to be a safe, effective, and realistic alternative to surgery. Preliminary data indicate that side effects, mainly in terms of uterine pain, may be further reduced if treatment with mifepristone is combined with a lower dose of prostaglandin. In addition, the approach may be more convenient to use if ongoing trials confirm that oral administration of misoprostol is an effective alternative to gemeprost.

REFERENCES

Aubény, E., and Baulieu, E.E. Activité contragestive de l'association au RU 486 d'une prostaglandin active par voie orale. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences (Paris) 312:539–545, 1991.

Bygdeman, M., and Swahn, M.L. Progesterone receptor blockage. Effect on uterine contractility in early pregnancy. Contraception 32:45–51, 1985.

Cameron, I.T., Mitchie, A.F., and Baird, D.T. Therapeutic abortion in early pregnancy with antiprogestogen RU 486 alone or in combination with a prostaglandin analogue (gemeprost). Contraception 34:459–468, 1986.

Couzinet, B., Le Strat, N., Ulmann, A., et al. Termination of early pregnancy by the progesterone antagonist RU 486 (mifepristone). New England Journal of Medicine 315:1565–1570, 1986.

Dubois, C., Ulmann, A., Aubery, E., et al. Contragestion par le RU 486: Interet de l'association a un derive prostaglandine. Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Seances de l'Academie des Sciences (Paris) 306:51–61, 1988.

Frydman, R., Taylor, S., and Ulmann, A. Transplacental passage of mifepristone. Lancet 2:1252, 1985.

Gemzell, K., Swahn, M.L., and Bygdeman, M. Regulation of nonpregnant human uterine contractility. Effect of antihormones. Contraception 42:323–335, 1990.

Gemzell, K., Swahn, M.L., and Bygdeman, M. The effect of antiprogestin, hCG and a prostaglandin analogue (Misoprostol) on human uterine contractility. Contraception 1993 (in press).

Herrmann, W., Wyss, R., Riondel, A., et al. Effet d'un stéroide anti-progestérone chez la femme: Interruption du cycle menstruel et de la grossesse au début. Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences (Paris) 294:933–983, 1982.

Kovacs, L., Sas, M., Resch, B.A., et al. Termination of very early pregnancy by RU 486—an antiprogestational compound. Contraception 29:399–410, 1984.

Lim, B.H., Lees, D.A.R., Bjornsson, S., et al. Normal development after exposure to mifepristone in early pregnancy. Lancet 336:257–258, 1990.

Norman, J.E., Thong, K.J., and Baird, D.T. Uterine contractility and induction of abortion in early pregnancy by misoprostol and mifepristone. Lancet 338:1233–1236, 1991.

Peyron, R., Aubény, E., Targosz, V., et al. Early pregnancy interruption with mifepristone (RU 486) and the orally active prostaglandin misoprostol. New England Journal of Medicine 328:1509–1513, 1993.

Pom, J.C., Imbert, M.C., Elefant, E., et al. Development after exposure to mifepristone in early pregnancy. Lancet 338:763, 1991.

Puri, C.P., and Van Look, P.F. Newly developed competitive progesterone antagonists for fertility control. Antihormones in Health and Disease. Frontiers of Hormone Research 19:127–167, 1991.

Rådestad, A., and Bygdeman, M. Cervical softening with mifepristone (RU 486) after

pretreatment with naproxen. A double-blind randomized study. Contraception 45:221–227, 1992.

Rådestad, A., Bygdeman, M., and Green, K. Induced cervical ripening with mifepristone (RU 486) and bioconversion of arachidonic acid in human pregnant uterine cervix in the first trimester. A double-blind, randomized biomechanical and biochemical study. Contraception 41:283–292, 1990.

Silvestre, L., Peyron, R., and Ulmann, A. Sequential treatment with an antiprogestin (mifepristone, RU 486) and a prostaglandin analogue for termination of pregnancy. Abstract, VIIIth World Congress in Human Reproduction, Bali, p. 43, April 4–9, 1993.

Smith, S.K., and Kelly, R.W. The effect of the antiprogestin RU 486 and ZK 98,734 on the synthesis and metabolism of prostaglandins F 2a and E2 in separated cells from early human decidua. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 65:527–534, 1987.

Swahn, M.L., and Bygdeman, M. The effect of the antiprogestin RU 486 on uterine contractility and sensitivity to prostaglandin and oxytocin. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 95:126–134, 1988.

Swahn, M.L., Gottlieb, C., Green, K., et al. Oral administration of RU 486 and 9-methylene PGE2 for termination of early pregnancy. Contraception 41:461–473, 1990.

U.K. Multicentre Trial. The efficacy and tolerance of mifepristone and prostaglandin in first trimester termination of pregnancy. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 97:480–486, 1990.

Ulmann, A., Silvestre, L., Chemama, L., et al. Medical termination of early pregnancy with mifepristone (RU 486) followed by a prostaglandin analogue. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica (Umea) 71:278–283, 1992.

Van Look, P.F., and Bygdeman, M. Antiprogestational steroids: A new dimension in human fertility regulation. Oxford Reviews of Reproductive Biology 11:2–60, 1989.

World Health Organization (WHO), Task Force on Postovulatory Methods for Fertility Regulation. The use of mifepristone (RU 486) for cervical preparation in first trimester pregnancy termination by vacuum aspiration. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 97:260–266, 1990.

World Health Organization (WHO), Task Force on Postovulatory Methods for Fertility Regulation. Pregnancy termination with mifepristone and gemeprost: a Multicenter comparison between repeated doses and a single dose of mifepristone. Fertility and Sterility 56:32–40, 1991.