8

Honduras: Population, Inequality, and Resource Destruction

Billie R. DeWalt, Susan C. Stonich, and Sarah L. Hamilton

The population of Honduras in 1989 was estimated at 4.98 million people, nearly double the 1970 population of 2.63 million. During the same period, the country experienced environmental destruction on a grand scale. Soil erosion, watershed deterioration, deforestation, and destruction of coastal resources occurred at alarming rates. Based on appearances, there seems to be a direct link between the rapid population increase and this nonsustainable utilization of land and water resources. The purpose of this case study is to examine the evidence concerning population increase and natural resource destruction to determine whether there is such a direct link.

The accumulated evidence concerning southern Honduras is remarkably consistent in showing that environmental destruction is attributable more to the inequality of resource distribution and patterns of economic development in the region rather than to population increase. Although our evidence relates primarily to Honduras, it appears that these same processes have also been characteristic of other Central American countries and that they have played a major role in causing the violent conflicts and environmental difficulties that characterize the region today (see Williams, 1986; Leonard, 1987).

HONDURAS: AN OVERVIEW

With an area of 43,277 mi2 (a bit larger than the state of Kentucky), Honduras is the second largest of the Central American republics. Over 80

percent of the land is mountainous, a physical feature that contributes to the relative isolation of some areas of the country.

Honduras is predominantly an agricultural country. In 1980, 60 percent of the population was directly involved in agriculture (World Bank, 1991:297), and in 1987 agriculture accounted for 83 percent of the value of merchandise exports. The major exports in order of importance were bananas, coffee and cacao, fish and shellfish, wood products, fruits, nuts, flowers, sugar, and livestock products.

Southern Honduras is more dependent on agriculture than is the rest of the country. Approximately 70 percent of its population is directly dependent on agriculture for their livelihood. For this reason, changes in land utilization patterns in the region have an immediate and discernible effect.

THE POPULATION SITUATION

Although the total fertility rate for Honduras dropped from 7.4 in 1970 to 5.4 in 1989, and the annual growth rate declined from 3.71 percent (1981–1982) to 2.96 percent (1988–1989), the country's population continues to grow rapidly. Population density has climbed from 12.2 persons/km2 in 1950 to 35.6 in 1985 (see Stonich, 1986:145).

This population expansion has occurred in a nation characterized by extreme inequality of wealth1 and one of the lowest per capita incomes in Latin America (Sheahan, 1987). Additionally, Honduras exhibits one of the highest rates of rural destitution in Latin America (57–75 percent, depending on the measures used, in the 1970s). Unequal distribution of resources between rural and urban populations and within the rural sector means that more than 70 percent of rural families lived on less than $20 per month in 1980 (CSPE/OEA, 1982).

Honduras has been designated a "food priority country" by the United Nations. Per capita domestic food production has declined; Honduras has been a net importer of maize, rice, sorghum, and beans since 1976. In 1975, the prevalence of second-and third-degree malnutrition was 38 percent (Teller et al., 1979), and over 70 percent of children under 5 Years of age suffered from some form of protein-calorie malnutrition during the 1970s (SAPLAN, 1981). In the late 1980s, the average energy deficit in rural areas was approximately 20 percent (USAID Honduras, 1989a).

CHANGING LAND USE PATTERNS IN THE SOUTH

Southern Honduras experienced a substantial expansion of commercial agriculture in the years immediately following World War II. The Honduran government became an active agent of development, creating a variety of state institutions and agencies to expand government services, modernize the country's financial system, and undertake infrastructural projects.

This period of intensified public sector investments coincided with temporary high prices on the world market for primary commodities like cotton, coffee, and cattle. Large landowners in the south who had access to the good lands on the coastal plain had historically been unable to respond to favorable economic conditions because of the lack of necessary infrastructure such as transportation, markets, and credit. With the infrastructure in place these owners found it profitable to expand production for the global market.

The Cotton Boom

It was cotton cultivation that first transformed traditional social patterns of production in southern Honduras (Stares, 1972:35; White, 1977; Durham, 1979:119; Boyer, 1983:91). In the late 1940s and 1950s, people from El Salvador began commercial cultivation of cotton in Honduras.2 As in El Salvador and Nicaragua, commercial production involves considerable mechanization in land preparation, planting, cultivation, and aerial spraying. Cotton cultivation along the Pacific coastal plain also is dependent on

the heavy use of chemical inputs (especially insecticides and fertilizers). The indiscriminate use of pesticides in the cotton growing regions remains one of the most pervasive environmental contamination and human health problems throughout Central America. Water from cotton growing areas shows heavy contamination from DDT, Dieldrin, Toxaphene, and Parathion (USAID, 1982), and the results of a 1981 study to determine the levels of pesticide poisoning in the area around the city of Choluteca revealed that approximately 10 percent of the inhabitants had pesticide levels sufficiently high to be considered cases of intoxication (Leonard, 1987:149). The land and water contamination from pesticides, as well as high levels of pesticide residues in food supplies, have had substantial effects on human health (Williams, 1986; Leonard, 1987).

Following the boom and bust cycles of the international cotton market, the amount of land in cotton in southern Honduras fluctuated considerably between the late 1940s and the late 1980s. The major social effect of the cotton boom was to increase inequalities in access to land. Large landowners revoked peasant tenancy or sharecropping rights, raised rental rates exorbitantly, and evicted peasants forcibly from national land or from land of undetermined tenure (Durham, 1979; Boyer, 1983:94). Thus, one of the effects of increased cotton cultivation was to displace many poor farmers from the most suitable agricultural lands in the south. Cotton also, however, provided a substantial number of seasonal jobs during the harvest season. The long staple cotton grown in the region was, and still is, largely picked by hand.

The Cattle Boom

The expansion of the cattle industry has probably had the most extensive and devastating environmental impact (DeWalt, 1983; 1986). Between 1960 and 1983, 57 percent of the total loan funds allocated by the World Bank for agriculture and rural development in Central America supported the production of beef for export. During that same period, Honduras obtained 51 percent of the total World Bank funds that were disbursed in Central America—of which 34 percent were for livestock projects (calculated from Table 4-1 in Jarvis, 1986:124).

These programs were all channeled into the region through the large landowners, merchants, and industrialists who made up the elites of the countries (DeWalt, 1986; Stonich and DeWalt, 1989). In a context of declining agricultural commodity prices, high labor costs, unreliable rainfall, and international and national support for livestock, landowners reallocated their land from cotton and/or grain cultivation to pasture for cattle. Cattle appealed to landowners in Honduras because it is a commodity that could be produced with very little labor. While it takes considerable human labor

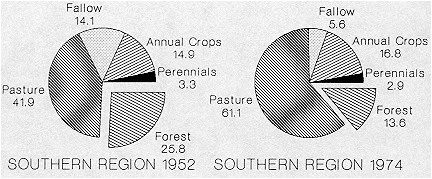

Figure 1 Changing land use patterns: southern Honduras, 1952–1974. (All figures are percentages.) SOURCE: DGECH (1954, 1976).

to produce sugar cane, cotton, melons, or coffee, with just two or three hired hands and extensive pasture it is possible to manage a herd of several hundred cattle.3 In Honduras, land reform programs ironically also encouraged the expansion of pasture for livestock. Landowners who feared expropriation of unutilized fallow and forest land fenced it and planted pasture as a way of establishing use of the land without increasing labor inputs (DeWalt and DeWalt, 1982:69; Jarvis, 1986:157).

The main limitation to beef production is pastureland, and this is why there were such extensive changes in land use patterns in Honduras and the other Central American countries during the 1960s and 1970s. Expansion took place not only in the lowlands and foothills where cattle raising traditionally occurred, but also in the highlands where many of the wealthier peasant farmers augmented cattle production (Durham, 1979; Boyer, 1983; Stonich, 1986). Increased livestock production in the lowlands and the highlands also accelerated the expulsion of peasants from national and private lands (White, 1977:126–156; Stonich, 1986:139–143). Between 1952 and 1974, pasture in the region increased from 41.9 percent of the land to 61.1 (see Figure 1). Precipitous declines are evident in both fallow land and the amount of land in forest. This has resulted in significant increases in both soil erosion and deforestation.

Honduras is losing its soils at the rate of 10,000 ha per year and, if current trends continue, ''the forest resource will be exhausted in a generation'' (USAID Honduras 1990:3). Many of the best lands in the country are

in pasture. The Central Bank estimated in August 1988 that 48 percent of the valley lands in Honduras—covering 31 principal valleys—are in pasture. Of these, 22 percent are located in the southern part of the country (USAID Honduras, 1990:10). While the livestock boom has ended in several of the other Central American countries, the number of cattle in Honduras continues to grow rapidly.

Cantaloupe and Shrimp

Because of a decline in demand for beef and falling prices, in the late 1980s capitalist investors in southern Honduras began investing in two new nontraditional export crops—cantaloupe and shrimp. During the 1980s, cantaloupe production expanded at a rate of 23 percent per year and shrimp production at a rate of 22 percent (USAID Honduras, 1990:2), and in 1989–1990 these two commodities contributed an estimated $25 million in export earnings to the Honduran economy (Meckenstock et al., 1991:4). These earnings have been offset by both environmental and social costs.

The area planted in cantaloupe is projected to reach 9,000 ha by 1996. On the positive side, cantaloupe production provides a substantial number of temporary jobs in production and in packing for export. Accompanying the boom in production, however, have been escalating levels of soil degradation, aphid-borne viruses, and insect pests like leaf miners and whiteflies. Even with two to three applications of pesticides a week, crop losses in 1989–1990 were 56 percent of harvest projections (Meckenstock et al., 1991:5). Runoff of pesticides poses a threat to community water supplies ill the region as well as to the estuaries in the Gulf of Fonseca where shrimp farming has become a big business and where shrimp larvae already show relatively high levels of DDT.

The area in shrimp farms increased from about 100 hectares in 1982 to 11,515 hectares in 1992. The expansion of shrimp farms has occurred in areas of mud flats, beaches, and mangroves that were once public lands used by the rural poor for hunting, fishing, and the gathering of shellfish. Government concessions to shrimp companies have effectively turned these areas into private property. Twenty-year concessions have been granted to companies for 4 lempiras (less than $1) per hectare per year. Fences are erected, armed guards installed, and local people excluded from areas they had once freely utilized.

Parallels in the social process associated with the recent boom in shrimp mariculture and the earlier expansions of export commodities (cotton, sugar, and livestock) in the region are striking. Past "enclosure movements" in which small farmers were removed from relatively good agricultural land, often by force and with the compliance of local authorities, are being repeated on the intertidal lands. Intertidal land once open to public use for

fishing, shellfish collecting, salt producing, and the cutting of firewood and tanbark is now being converted to private use. Concessions, guarantees of occupancy, and titles have been acquired by the firms involved in shrimp production. Conflicts have arisen among the large foreign-owned operations, local medium-scale entrepreneurs, and campesino cooperatives over access to estuaries, lagoons, and mangroves. Three fishermen died in incidents involving shrimp farms in 1991 and 1992.

Moreover, although development documents written in the mid-1980s stressed the importance of incorporating resource-poor households in the development process primarily through the formation and support of shrimp farming cooperatives (USAID, 1985), more recent reports conclude that only the larger, more intensive operations are profitable (USAID Honduras, 1989b). These large operations generate very few employment opportunities, typically employing fewer than one person per hectare (Gonzalez et al., 1987; cited in SECPLAN/DESFIL, 1989:179).

The construction of shrimp farms has also exacerbated the destruction of mangrove forests along the coast. This may eventually become as extensive as the mangrove destruction that occurred along the coast of Ecuador in connection with development of shrimp farming in that country (LACR, 1989).

Summary

During the last 40 years, the restructuring of agriculture in southern Honduras has impoverished both the landscape and an increasing percentage of the population.4 The general trend has been toward resource oligopoly, patterns of exploitation and production that jeopardize future systemic sustainability in exchange for quick profits, wanton destruction of natural resources, and underemployment. None of these processes resulted, even indirectly, from population pressure.

SMALLHOLDER AGRICULTURE

Until now, we have been talking about a relatively small percentage of producers, those with access to the best lands and the most resources. Indeed, as already implied, land distribution in Honduras is highly unequal. Table 1 compares the distribution of land in the municipality of Pespire in southern Honduras, and in the country as a whole.5 Landholding patterns are remarkably consistent across local, regional, and national levels. Approximately two-thirds of producers have access to less than 5 ha of land; this multitude share only 9–10 percent of the total land area. In contrast, the 10–12 percent of the population with access to over 50 ha controls more than 50 percent of the land area. These are the commercial producers on whom the previous section focussed. The question remains, what is happening to the small producers, the majority of the population, as large commercial concerns expand?

Most small producers are concentrated on steep mountain slopes that are of marginal quality for agriculture (the brief descriptions below are based on three small communities we studied in the municipality of Pespire).6 Although large landholdings are relatively rare in the communities studied

TABLE 1 Comparison of Inequality of Landholding in Pespire, in Southern Honduras, and in Honduras

|

Size of Holdings (ha) |

Percentage of Farms |

Percentage of Area |

||||

|

Pespire |

South |

Honduras |

Pespire |

South |

Honduras |

|

|

<5 |

63.4 |

68.4 |

63.9 |

10.1 |

10.3 |

9.1 |

|

5–9.9 |

15.9 |

13.6 |

14.5 |

9.9 |

8.1 |

7.7 |

|

10–19.9 |

9.8 |

8.8 |

9.8 |

12.2 |

10.4 |

10.2 |

|

20–49.9 |

7.4 |

6.0 |

7.8 |

19.6 |

14.8 |

17.5 |

|

50–99.9 |

2.2 |

1.7 |

2.3 |

12.8 |

9.5 |

11.5 |

|

≥100 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

1.7 |

35.3 |

46.8 |

44.0 |

|

Total no. of farms |

1,714 |

25,412 |

195,341 |

|

|

|

|

Total no. of ha. |

|

|

|

19,383 |

304,462 |

2,629,859 |

TABLE 2 Comparison of Land Tenure Characteristics in the Highland Communities Studied

(see Table 2), there is considerable inequality in access to land among smallholders. The mean size of landholdings for all of the communities is quite small (less than 6 ha). While the percentage of surveyed households owning land ranges from 27 percent to 72 percent by community (see Table 2), a large percentage of people in all communities are landless or have access to less than one ha of land. In the villages around Cacautare, 54 percent of the sample rented, borrowed, or sharecropped land, generally in quantities smaller than 5 manzanas (less than 3.45 ha).7 Most landowners had access to less than 7 ha of land. Only two individuals held more than 28 ha, with the largest being about 39 ha.

In these communities, landowners and renters generally practice some form of shifting cultivation8 that involves interplanting maize and sorghum.

The first year of cultivation of a plot of hillside land in Cacautare usually begins with a slash-and-mulch system in which maize or sorghum is planted. When planting maize, all brush, vines, and weeds are cut down in August.9 A digging stick is used to plant maize among the decaying vegetation. After the maize has germinated, the larger trees are felled and left in the field. When sorghum is planted, the seeds are broadcast-sown under second growth forest; then the trees, brush, and weeds are cut. In both cropping systems, the decaying vegetation is left in the field as a mulch. In the second (and sometimes third) year of cultivation, the now-dry brush and trees are burned in April and maize and sorghum are interplanted.10 In the past, much of this land would then be allowed to lie fallow for a long period of time to recover its fertility. Now, however, an increasing proportion of the land, especially among larger landowners, is being converted to pasture. As Figure 1 showed, the percentage of land in pasture in the south of Honduras expanded by half in only 20 years, and at the expense of forest and fallow land.

Landless peasants provide the labor required to convert land to pasture in exchange for temporary but inexpensive land rental. Poor peasants in Cacautare had relatively little difficulty renting land in the early 1980s. The rental cost of 1 manzana of land in 1981 was only about $8, with the renter agreeing to leave the crop residue in the field. While haulm used for grazing animals in the dry season was worth up to $50 per manzana, rental costs still seemed relatively low.

Landowners are willing to rent their land cheaply because the most expensive and labor-intensive aspect of hillside agriculture is clearing secondary growth forest. Rather than paying laborers to cut brush and trees, landowners rent their land to the landless for a year or two. Part of the rental agreement is that pasture grasses will be sown in the field between rows of subsistence crops so that the landowner will be left with a new pasture. We estimate that this arrangement saves the landowner at least $100 in labor costs for each hectare of new pasture (see DeWalt and DeWalt, 1982).

Why are landowners more interested in growing pasture to feed livestock than in growing basic grains or export crops (cf. Parsons, 1976:126)?

The main reason is that the potential return on investment from 1 manzana of grain in the harsh, risky environment of southern Honduras is minimal. In the best case scenario (i.e., highest market price, lowest input prices), farmers are able to make a profit of only about $75 per manzana (DeWalt, 1985:177–178). This potential profit is not enough to entice most larger landowners to produce grain beyond what they require for their own consumption.11

For farmers with sufficient land, there is a much more lucrative option available in raising livestock.12 Several of the relatively well-off smallholders with whom we spoke in Cacautare reported that they had little interest in planting sorghum and maize because they were not profitable crops. They said that market prices were too low, labor costs had climbed, laborers no longer worked as hard as they did in the past, and the weather, insects, and other natural forces made grain harvests too unpredictable. Our calculations indicate that their average profit from selling one steer exceeded the total profit from several manzanas of grain. As a result, the 12 largest landowners in our sample had begun converting significant portions of their land into pasture.13

The environmental result of pasture expansion and land concentration is substantial pressure on the land-resource base and its degradation. Farmers in Cacautare reported that fields should be cultivated for only 3 years in a row (mean = 2.93, range = 1 to 5 years) and should lie fallow for at least 6 years (mean = 6.22, range = 1 to 15 years). Both Stonich (1986, in press) and Durham (1979) demonstrate a direct relationship between the size of landholdings and the amount of time fields lie fallow. Table 3 shows this relationship for the highland villages around Esquimay. Farmers with over

TABLE 3 Agricultural Practices by Land-Tenure and Farm Size in Southern Highland Villages, 1983

|

Type of Tenancy |

N |

Percentage of Land in Food Cropsa |

Percentage of Land in Pasture |

Mean No. of Cattle Owned (range) |

Length of Fallow (yr) |

|

Rentersb |

74 |

95 |

— |

0.17(0–4) |

2.7 |

|

Owners |

|||||

|

<1 hac |

23 |

80 |

— |

0.22 (0–3) |

2.7 |

|

1–4.9 ha |

87 |

51 |

4 |

0.22 (0–3) |

3.2 |

|

5–19.9 ha |

15 |

23 |

21 |

2.5 (0–13) |

3.8 |

|

20–50 ha |

5 |

6 |

48 |

8.0 (7–9) |

5.0 |

|

>50 ha |

1 |

6 |

20d |

50.0 (50) |

6.0 |

|

a Maize, sorghum, and beans. b Mean area of rented land = 1.4 ha. c Of the owners, 51 percent also rent land. d The largest landowner rents additional grazing land in the lowlands. SOURCE: Stonich (1989:287). |

|||||

20 ha allow their land to lie fallow for 5 to 6 years. Those with less land resume cultivation of their land after it has been fallow for only 2 or 3 years (cf. Durham, 1979:144–45). Boyer (1983) reports that in other communities in the south, a fallow period is no longer part of the agricultural system.

Increasing intensity of land use means that yields are much lower, soil fertility is rapidly depleted, and soil erosion is exacerbated. Lack of vegetation on the hillsides also causes frequent landslides when torrential rains hit the region.

For the land-poor, the expansion of pasture threatens not only the fertility of the land but also its availability. Their dilemma was succinctly expressed by one of our informants:

Right now we have land available to rent, but each year you can see the land in forest disappearing. In a few years, it will all be pasture and there will be no land available to rent. How are we to produce for our families then? We see what is happening, but we have no choice because our families have to eat now.

POPULATION GROWTH AND LAND USE CHANGES

Southern Honduras is the most densely settled region of the country; it comprises only 5 percent of the total area of the country but contains approximately 11 percent of the population. Population density increased from 29.8 persons/km2 in 1950 to 63.9 in 1985 (Stonich, 1986:145). Popu-

TABLE 4 Population Density, Number of Years of Fallow, and Ratio of Length of Cropping Cycle to Total Cyclea, 1950 to 1990

|

|

Period |

|||

|

Characteristics |

1950 |

Mid-1970s |

Mid-1980s |

1990 |

|

Western and eastern highlands |

||||

|

Population density (inhab./km2) |

63 |

99 |

110 |

130 |

|

Years of fallow |

3 to 5 |

0 to 2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Ratiob |

.38 to .6 |

.6 to 1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Central highlands |

||||

|

Population density (inhab./km2) |

35 |

54 |

68 |

74 |

|

Years of fallow |

15 to 20 |

10 to 15 |

2 to 6 |

0 to 3 |

|

Ratio |

.13 to .16 |

.16 to .23 |

.38 to .6 |

.6 to 1 |

|

a Total cycle = years of cultivation plus years of fallow. b The number of years the land is cultivated divided by the number of years the land is fallow. SOURCE: Stonich (1990). |

||||

lation densities are as high as 160 persons/km2 in some counties (Stonich, 1989:277). Although the natality rate is higher than the national average, growth rates have not kept pace with the rest of the nation—due in part to an infant mortality rate that is 20 percent higher than the national average and in part to regional outmigration. In our research communities, the high regional natality rate is dramatically manifested. The community surveys record an average of 6.3 live births per woman, and many women had yet to complete their families.

Table 4 shows the relationship over time between the increasing population density of highland communities and the number of years the land was allowed to remain fallow. Since 1950, the amount of time fields have been allowed to remain fallow has declined precipitously (Stonich, 1986; Boyer, 1983).14 As the population density of these highland communities has increased, there has been a corresponding increase in the intensity of land use. Yet simultaneous population increase is not a sufficient causal explanation for the intensity of land use, destruction of forests, soil erosion, or other ecological problems of the region. Inequality in access to land and the investment patterns of large landowners, neither of which depend on

population pressure, are much more important factors. As we have shown, the expansion of livestock and other commercial agricultural concerns has: (1) created ecological problems because of the heavy use of pesticides, destruction of mangroves in coastal areas, and the mining of land resources; (2) resulted in a continuing decrease in wage-labor opportunities in the region; and (3) removed the poor from access to the better lands; the displaced poor, in turn, have caused ecological problems through the overuse of steep hillside lands on which they are forced to eke out a living.

Although the ecological consequences of commercial agricultural expansion are quite pronounced, it must be emphasized that the social consequences are even more serious. Rural unemployment averaged 62.2 percent over the annual cropping cycle in 1980 (CONSUPLANE, 1982); this figure underestimates unemployment, as women were not included. Since 1980, decreasing cotton and coffee production in the region has further limited agricultural employment opportunities. The result is that many households are unable to satisfy their most basic needs. The national planning agency (SAPLAN, 1981) estimated that 41 percent of all southern families did not meet minimum subsistence levels, and that families living in "semiurban communities" consumed even fewer calories than rural families (Stonich, 1986:152–154).15

Data that we collected in 1982 in nine highland and lowland communities showed that 65 percent of the children under 60 months of age were stunted (below 95 percent of the standard height-for-age recommended by the World Health Organization) and 14 percent were wasted (below 90 percent of the standard weight-for-height). Furthermore, in a region in which cattle production is so pervasive, only 3 percent of all the protein consumed by these villagers comes from meat. While most families had access to sufficient protein, half failed to meet energy requirements in some communities (DeWalt and DeWalt, 1987:39). Infant mortality averaged 99/ 1,000, and an average of 16 percent of all children born in the communities did not survive beyond the age of five. Both undernutrition and child mortality are directly related to the inability of farm families to gain access to enough land to sustain themselves (DeWalt and DeWalt, 1982, 1989; Durham, 1979).

When families cannot survive on the land, they seek opportunities elsewhere (Durham, 1979). Thus, the problems plaguing the south are being exported to other regions of the country. Poor families increasingly engage

in cyclical or permanent migration to the cities or depend on remittances from family members. Since 1974, out-migration from the Southern region has averaged 1.3 percent annually. Approximately half as many people leave the region permanently every year as are added to the population by both its high birth rate and in-migration. In the communities we have studied, 70 percent of male household heads and 20 percent of female household heads in Cacautare had migrated at least once to work outside the community. In villages around Esquimay, 39 percent of children over 13 years of age had migrated. Most of these migrants end up in the cities of Honduras.

The urban population growth rate in Honduras was 5.8 percent between 1974 and 1980, and 5.4 percent between 1980 and 1987, a rate much higher than the population growth rate of about 3.5 percent (USAID, 1989a). The squalid slums on the edges of Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula attest to the environmental problems caused by this rural-to-urban migration.

Migrants from degraded areas in the south are also settling in Olancho and the vast, relatively unpopulated areas of the Mosquitia in northeastern Honduras—including the Rio Platano Biosphere Reserve. Similar to processes occurring in other areas of Latin America, deforestation has taken a heavy toll on the ecosystems as newly arriving colonizers clear forest for crops, cattle, and fuelwood. The cleared lands often end up in the hands of extensive cattle ranching interests as the colonists move further into the forest, simultaneously encroaching upon lands inhabited by the small remaining indigenous population.

The consequences of land concentration and the expansion of environmentally costly commercial agriculture have been most severe for those who are powerless to alter the course of these events, but the economic and environmental sustenance of all of Honduran society is threatened by these processes.

CONCLUSION

The implications of this case study are clear: A decline in population growth will not have a major impact on slowing the rate of natural resource destruction in Honduras. In southern Honduras, environmental degradation and social problems often attributed to population pressure arise from glaring inequalities in the distribution of land, the lack of decent employment opportunities, and the stark poverty of many of the inhabitants. It is not the carrying capacity of the land that has failed to keep pace with population growth. Neither is population growth the primary cause of the impoverishment of the Honduran ecology and its human inhabitants. While the destruction caused by the poor in their desperate search for survival is alarming, it pales in comparison with the destruction wrought by large landowners through their reckless search for profit.

REFERENCES

Boyer, Jefferson 1983 Agrarian Capitalism and Peasant Praxis in Southern Honduras. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

CONSUPLANE (Secretaria Técnica del Consejo Superior de Planificación Ecnnómica) 1982 Las Regiones: Planificación. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: CONSUPLANE.

CSPE/OEA (Secretaria Técnica del Consejo Superior de Planificación Económica y Secretaria General de la Organización de Estados Americanos) 1982 Proyecto de Desarrollo Local del Sur de Honduras. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: CSPE\OEAO.

DeWalt, B.R. 1983 The cattle are eating the forest. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 39:18–23.

1985 Microcosmic and macrocosmic processes of agrarian change in southern Honduras: the cattle are eating the forest. Pp. 165–186 in B.R. DeWalt and P.J. Pelto, eds., Micro and Macro Levels of Analysis in Anthropology Issues in Theory and Research. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

1986 Economic assistance in Central America: development or impoverishment? Cultural Survival Quarterly 10:14–18.

DeWalt, B.R., and P. Bidegaray 1991 The agrarian bases of conflict in Central America. Pp. 19–32 in K. Coleman and G. Herring, eds., Understanding the Central American Crisis: Sources of Conflict, U.S. Policy, and Options for Peace. Wilmington, Del.: SR Books.

DeWalt, B.R., and K.M. DeWalt 1982 Cropping Systems in Pespire, Southern Honduras. Farming Systems Research in Southern Honduras Report No. 1. Lexington: Department of Anthropology, University of Kentucky.

DeWalt, K.M., and B.R. DeWalt 1987 Nutrition and agricultural change in southern Honduras. Food and Nutrition Bulletin 9(3):36–45.

1989 Incorporating nutrition into agricultural research: a case study from southern Honduras. Pp. 179–199 in J. van Willigen, B. Rylko-Bauer, and A. McElroy, eds., Making Our Research Useful: Case Studies in the Utilization of Anthropological Knowledge. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

DGECH (Dirección General de Estadística y Censos) 1954 Censo Nacional Agropecuario 1952. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: Dirección General de Estadística y Censos.

1968 Censo Nacional Agropecuario 1965. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: Dirección General de Estadística y Censos .

1976 Censo Nacional Agropecuario 1974. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: Dirección General de Estadística y Censos.

Durham, W. 1979 Scarcity and Survival in Central America: Ecological Origins of the Soccer War. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

Gonzalez, J.R., D. de Maradiaga, and M.A. Perdomo 1987 Situación de la Carcinocultura en la Costa Sur de Honduras. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: RENARE (cited in SECPLAN/DESFIL, 1989).

Guess, G.M. 1979 Pasture expansion, forestry, and development contradictions: the case of Costa Rica. Studies in Comparative International Development 14:42–55.

Jarvis, L.S. 1986 Livestock Development in Latin America. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

LACR (Latin American Commodities Report) 1989 Shrimp/Ecuador. Latin American Commodities Report. CR-89-09 (15 September):8. London: Latin American Newsletters Ltd.

Leonard, H.J. 1987 Natural Resources and Economic Development in Central America. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Books.

Meckenstock, D., D. Coddington, J. Roses, H. van Es, M. Chinman, and M. Murillo 1991 Honduras Concept Paper: Towards a Sustainable Agriculture in Southern Honduras. Paper presented at the International Sorghum/Millet Collaborative Research Support Conference, Corpus Christi, Texas, July 8–12.

Parsons, J.J. 1976 Forest to pasture: development or destruction? Revista de Biologia Tropical 24(Suppl. 1):121–38.

SAEH/INCAP (Servicio de Alimentación Escolar de Honduras/ Instituto de Nutrición de Centro América y Panama) 1987 Primer Censo Nacional de Tulle en Escolares de Primer Grado de Educación Primaria de la República de Honduras, 1986. Tegucigalpa, Honduras:

SAEH/ INCAP. SAPLAN (Sistema de Análisis y Planificación de Alimentación y Nutrición) 1981 Análisis de la Situación Nutricional durante el Periodo 1972–1979. Mimeograph. Consejo Superior de Planificación Económico, Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

SECPLAN (Secretaria de Planificación, Coordinación, y Presupuesto) and DESFIL (Development Strategies for Fragile Lands) 1989 Perfil Ambiental de Honduras 1989. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: SECPLAN.

Sheahan, J. 1987 Patterns of Development in Latin America. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Stares, R.C. 1972 La Economia Campesina en la Zone Sur de Honduras, 1950–1970: Su Desarrollo y Perspectives pare el Futuro. Informe Presentado a la Prefecture de Choluteca, Honduras.

Stonich, S.C. 1986 Development and Destruction: Interrelated Ecological, Socioeconomic, and Nutritional Change in Southern Honduras. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan. Ann Arbor.

1989 The dynamics of social processes and environmental destruction: a Central American case study. Population and Development Review 15:269–296.

1990 Strategies to Enhance Household Agricultural Production and Rehabilitate Degraded Lands in Honduras. Paper presented at the 89th Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association, New Orleans, Louisiana, November 30. In Press Enduring Crises: The Political Ecology of Poverty and Environmental Destruction in Honduras. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

Stonich, S.C. and B.R. DeWalt 1989 The political economy of agricultural growth and rural transformation in Honduras and Mexico. Pp. 202–230 in S. Smith and E. Reeves, eds., Human Systems Ecology: Studies in the Integration of Political Economy, Adaptation, and Socionatural Regions. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

Teller, C., R. Sibrian, C. Talavera, V. Bent, J. del Canto, and L. Saenz 1979 Population and nutrition: implications of socio-demographic trends and differentials for food and nutrition policy in Central America and Panama. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 8:95–109.

USAID (United States Agency for International Development) 1982 Country Environmental Profile. Rosslyn, Va.: JRB Associates.

1985 Environmental Assessment of the Small Scale Shrimp Farming Component of the USAID/Honduras Rural Technologies Project. Gainesville, Fla.: Tropical Research and Development, Inc.

USAID Honduras 1989a Strategic Considerations for the Agricultural Sector in Honduras. Draft report. Office of Agriculture and Rural Development, USAID/Honduras, Tegucigalpa.

1989b Plan de Desarrollo del Camarón en Honduras. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: USAID.

1990 Agricultural Sector Strategy Paper. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: USAID Office of Agriculture and Rural Development.

White, R.A. 1977 Structural Factors in Rural Development: The Church and the Peasant in Honduras. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Cornell University.

Williams, R.G. 1986 Export Agriculture and the Crisis in Central America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

World Bank 1991 World Tables, 1991. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.