4

Changing Patterns of Water Resource Decision Making

Walter R. Lynn

Cornell University

Ithaca, New York

The emergence of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) presented everyone involved in water resources with a new set of challenges that included questioning our motives and the quality of our work. Even us ''good guys," whose only interest was to apply our vast technical knowledge and skills to improve the quality of life for the body politic, were suspect!

In my view the NEPA permanently changed the landscape for engineers, scientists, and everyone else involved in water resource issues—by altering the character and scope of acceptable professional practices.

The 91st Congress intended to accomplish a great deal when it passed the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, by proclaiming a statement of national policy and prescribing a methodology to accomplish those ends (and doing all that with extraordinary brevity). Section 101 (a) of Title I declares that:

The Congress, recognizing the profound impact of man's activity on the interrelations of all components of the natural environment, particularly the profound influences of population growth, and new and expanding technological advances and recognizing further the critical importance of restoring and maintaining environmental quality to the overall welfare and development of man, declares that it is the continuing policy of the federal government, in cooperation with state and local governments, and other concerned public and private organizations, to use all practicable means and measures, including financial and technical assistance, in a manner calculated to foster and promote the general welfare, to create and maintain conditions under which man and nature can exist in productive harmony, and fulfill the

social, economic, and other requirements of present and future generations of Americans.

The act also declared that the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was a process to reveal, consider, and evaluate what was proposed. While directed exclusively at federal agencies and other actions of the federal government, it effectively compelled everyone to examine and address the environmental consequences of actions that were being considered. For the engineering communities, it imposed the obligation to consider these issues early in the predesign process so that undesirable effects could be avoided or mitigated.

However, even though many believe otherwise, NEPA did not provide an avenue for individuals or organizations to prevent actions from taking place. Neither does it give authority to stop an action even if it were undeniably environmentally destructive. Rather, it assumes that the remedy for such extreme acts is embodied in the full disclosure that an EIS requires and that the political process is sufficiently robust to control such reprehensible acts. The early prominent role of the courts in addressing EIS complaints was to consider whether an EIS was required or to determine whether an EIS that had been prepared was adequate. After more than two decades, the smoke and thunder about those issues appears to have significantly abated.

Special interests take various forms, sometimes in support of an activity, sometimes opposed. The label "special interest" has come into relatively common and popular use. While the NEPA was intended to help ensure that innovators did not do something stupid and contrary to the public welfare, unfortunately it also provided avenues for those in opposition to derail or delay actions, off times for private reasons.

Development, economic growth, population growth, energy use, transportation, conservation, and pollution all directly affect water resources. These are contentious issues because our society has not yet reached a consensus about how to address or resolve them. However, while it may have slowed the pace of certain actions, it seems clear to me that NEPA has helped society to better articulate and define these complex issues in the process.

Before long the NEPA model and concepts were emulated by many of the states, and the requirement to address such perplexing questions was no longer delimited by a project's involvement by federal agencies or federal funds—everybody was doing it! Many from the engineering community initially viewed this as an unwarranted intrusion into their professional domain. There were many cries of anguish from practitioners, and other professionals who became enmeshed in complicated assessments of the consequences of practically all engineering and technical decisions and recommendations. (Admittedly some of these were pretty trivial and seemingly irrelevant.) On

the other hand, some found that opportunities to prepare or respond to an EIS spawned a new "cottage industry" that became a bread-and-butter item for many consulting firms.

Once the compelling character of this short but sweeping legislative initiative sunk in, it became clear to everyone in the water resources community that the fundamental policy issues targeted by NEPA would require new perspectives, insights, and skills. The experience over the past two decades has shown that NEPA permanently modified the culture and practices of engineers, scientists, and public officials by inculcating in them the obligation to give explicit consideration of environmental consequences of public or private acts that impinge upon the public.

While "existing in productive harmony with nature" fulfilling the "social, economic, and other requirements of present and future generations " was not part of the traditional science and engineering lexicon, neither was it a totally alien concept. However, to properly address these issues, it became apparent that individuals with relevant expertise became essential and directly involved in the process.

On March 4, 1974, with drought conditions looming large on the horizon for the Potomac basin, Congress mandated that the Secretary of the Army (acting through the Chief of Engineers):

... make a full and complete investigation and study of the future water resources needs of the Washington metropolitan area, including but not limited to the adequacy of present water supply, nature of present and future uses, the effect water pricing policies and use restrictions may have on future demand, the feasibility of utilizing water from the Potomac estuary, all possible water impoundment sites, natural and recharged ground water supply, wastewater reclamation, and the effect such projects will have on fish, wildlife, and present beneficial uses, and shall provide recommendations based on such investigations for supplying such needs. (NRC, 1984a)

The act also directed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to request the National Academy of Sciences/National Academy of Engineering to review and comment on the scientific bases for the conclusion reached in its studies of both an experimental water treatment plant for the Potomac estuary and a plan for future water supplies for the Washington metropolitan area.

In 1976 the National Research Council (NRC) agreed to undertake a study of future water supplies for the capital area, a second study of an experimental estuary water treatment plant (NRC, 1984b). Those of us involved learned a great deal. The use and abuse of the Potomac River basin had long been a

matter of concern for those whose lives and livelihoods were influenced and affected by current and future uses of that water resource. The Corps of Engineers, with regulatory responsibility for the Potomac River and for the water supply of the District of Columbia (viz., the Washington Aqueduct Division) was instructed by the Congress to study and recommend a "permanent solution" to the periodic droughts that threatened the metropolitan Washington area (MWA). While applauding the idea of final resolution to these problems, many living in the area viewed the Corps' role in this endeavor with some suspicion. (It is probably fair to say that the Corps at that time was thought by many to be dam-building zealots—and these views were reinforced by somewhat strident attacks on all large dam construction [see, e.g., Peterson, 1954].)

Congress's directive to the Secretary of the Army to request a review of the scientific conclusions reached in its report was intended to allay the suspicions of skeptics. The committee, on the other hand, was eager to prod the Corps into producing an exemplary study that would be a model for future water supply studies. Dan Okun, chairman of the study (in collaboration with Sheila David and Charlie Malone) recruited a committee for this task that included scholars and practitioners from economics, public administration, ecology, hydrology, systems engineering, and water supply engineering. Under Dan's leadership the committee concluded that it would be more effective and useful if it advised the Corps on its approaches and design for the studies as they evolved in addition to reviewing the final results, conclusions, and recommendations after the studies were completed.

The skills and competence needed to address the broad range of issues confronting the Corps in a study involving a 50 year planning horizon for the nation's capital dictated that the composition of the committee include members with expertise beyond the engineering aspects of public water supply systems. The amount of water supply capacity needed for the MWA required that methods for forecasting future demands for water would have to be developed; the biological, social, and political consequences of candidate impoundment (dam) sites would have to be evaluated; and the biological and chemical impacts on the estuary of withdrawals of water from the Potomac during drought periods would have to be analyzed and assessed.

The determination of future water resource needs and the means for satisfying these needs are only, in part, "scientific" questions. At the same time, proposed solutions to any engineering problem require judgment in order to balance technical and economic factors and issues of political feasibility and acceptability. The major questions the Corps of Engineers addressed required not only careful develop-

ment of the facts of the Metropolitan Washington Area (MWA), but also extrapolations of this information to a time some 50 years in the future. The time periods selected for planning such works may vary, as will the physical, chemical, biological, political, economic, social, and demographic environments of any study that strives to determine future water resources needs. (NRC, 1984a)

As the study neared completion, Professor William Corcoran (of Cal Tech), then a member of the NRC's Assembly of Engineering, recommended that the NRC recognize the need for a focused and visible effort directed at current and emerging water resource issues, especially within the federal agencies. After receiving much attention during the 1960s, the federal government dismembered many of the water resource policy-making structures it had created and left little to replace them. Thus, the NRC established the Water Science and Technology Board (WSTB), a body that could render advice to all federal agencies on matters pertaining to freshwater resources. It seems that the NRC acted wisely.

The kinds of advice that agencies sought and continue to seek from the WSTB have done much to shape the composition of the committees, panels, and the board itself. At the outset the questions posed centered primarily on engineering issues. But more and more the agencies were confronted with matters that were more comprehensive in scope and that demanded a broader range of skills and knowledge, which the board sought to provide on its panels and committees.

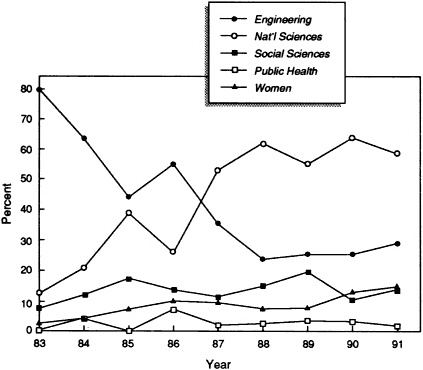

Accordingly, as shown in Figure 4.1, the composition of the panels and committees (and the board itself) reflected a changing array of issues ranging from engineering, the physical sciences, the social sciences, and public health.

I would be remiss if I did not call attention to an important accomplishment of the WSTB, namely, the recruitment of women engineers and physical and social scientists to serve on its committees. The staff (in the beginning by Sheila David) rendered a real service to the board through its efforts to identify women who were qualified to participate. It was soon discovered that the relatively low level of participation by women in these activities was less a matter of scarcity than identification. The payoff from the efforts of Sheila David and other members of the staff are also shown in Figure 4.1.

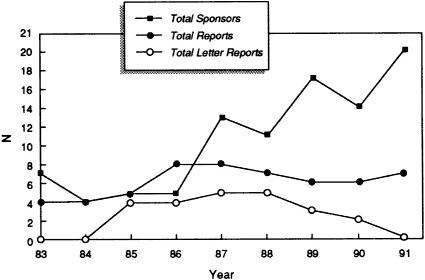

The extent of the importance and of the value of the board's work is reflected, in part, by the number of its sponsors as well as its productivity, as shown in Figure 4.2.

In conclusion, I believe that the National Environmental Policy Act has had a profound and lasting impact. It made all of us aware of and accountable for the planning, design, and operation of water resource systems. It has

Figure 4.1 Composition of WSTB committees in engineering, natural sciences, social science, public health, and percentage of females.

enlarged the context in which water resource issues are addressed. And most significantly it has helped us to internalize the social, public policy, and technical concerns and issues that ought to be included in assessing how water resources should be used. These changes have already influenced how we train and educate water resource professionals.

The WSTB has much to celebrate on its tenth anniversary. I believe the reasons for establishing the board are as valid today as they were a decade ago. If anything, water resource issues have become more critical in the face of the demands imposed by a growing U.S. population, burgeoning environmental insults, and global threats. Given the complexity of the issues and the off times political spin imposed solutions by the federal agencies, the WSTB provides a unique forum where these matters can be addressed in ways that assure independent and autonomous assessments. Congratulations!

Figure 4.2 Growth of WSTB sponsors and reports from 1983 to 1991.

REFERENCES

National Research Council (NRC). 1984a. Water for the Future of the Nation's Capital Area, 1984: A Review of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Metropolitan Washington Area Water Supply Study. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C. P.1.

National Research Council (NRC). 1984b. The Potomac Estuary Experimental Water Treatment Plant: A Review of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Evaluation of the Operation, Maintenance and Performance of the Experimental Estuary Treatment Plant. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

Peterson, E.T. 1954. Big Dam Foolishness. Devin-Adair, New York.