3

Governance Structures

THE ANTARCTIC TREATY SYSTEM

Background

From the early days of exploration, the territorial status of Antarctica has been a source of potential conflict. One group of states regards the continent as terra nullius: land belonging to no one, capable of appropriation by the normal methods of territorial acquisition—for example, discovery, exploration, effective occupation, or geographic continuity or contiguity. As of 1959, when the Antarctic Treaty was adopted, territorial claims had been made by seven of these states: Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom. The claims of Argentina, Chile, and the United Kingdom on the Antarctic Peninsula overlap; in aggregate, the claims cover more than 80 percent of the continent. A second group of states, the potential claimants, agree that Antarctica is terra nullius, but do not recognize the specific territorial claims of the seven claimant states and reserve the right to make claims of their own. This group includes the United States and the former Soviet Union (now Russia). Members of a third group of states recognize no territorial claims and make no claims of their own. Finally, a fourth group of states has asserted that the continent is the common heritage of mankind—that is, territory owned in common, whose benefits should be shared among all nations of the world.

International governance in Antarctica originated during the International Geophysical Year (IGY), which was organized by the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU) and ran from July 1957 to December 1958. The principal objective of the IGY was the comprehensive and coordinated accumulation of knowledge about the region. The 12 participating countries established more than 60 stations on or near the continent with more than 5,000 scientific and supporting personnel.

The success of the IGY made apparent the need for a more permanent system of international governance to address the potential sources of conflict on the continent (primarily the disputed territorial claims and the possible use of Antarctica for military purposes) and so provide a stable and reasonable environment for the continuation of cooperative scientific activities. Discussion among the United States and the 11 other governments active during the IGY led to the convening of an international conference in Washington, DC, in late 1959. This conference produced the Antarctic Treaty, which was signed December 1, 1959, and took effect June 23, 1961, upon ratification by the 12 participating states. Since then, two additional treaties have been adopted: the 1972 Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Seals, which took effect in 1978, and the 1980 Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), which took effect in 1982. A third agreement, the Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resources Activities (CRAMRA), was negotiated between 1982 and 1988, but has not taken effect. In 1991, the Parties to the Antarctic Treaty adopted a Protocol on Environmental Protection, which, when it takes effect, would supersede CRAMRA at least for 50 years. The Antarctic Treaty, together with the recommendations and measures adopted under it, and the Seals and Marine Living Resources Conventions, have collectively become known as the Antarctic Treaty System (ATS). A comprehensive analysis of the ATS is contained in Antarctic Treaty System: An Assessment (NRC, 1986b).

Basic Elements

The Antarctic Treaty established an innovative and flexible system of governance that has, on the whole, prevented conflict and promoted free and peaceful scientific cooperation for more than three decades. The Antarctic Treaty System rests on three basic principles.

First, Antarctica (defined as the area south of 60 degrees south geographic latitude) is to be a zone of peace. The Antarctic Treaty specifically provides that ''Antarctica shall be used for peaceful purposes only'' and prohibits all military activities, including the establishment of military bases, military maneuvers, and weapons testing (in particular, nuclear explosions) (Articles I, V).1 In this regard, the Antarctic Treaty was the first arms control treaty adopted since World War II. To verify compliance with these requirements,

the Treaty gives each Antarctic Treaty Consultative Party (ATCP)2 the right both to designate observers, who shall have "complete access at any time to any or all areas of Antarctica," and to make aerial observations anywhere in the Treaty area (Article VII).

Second, the Treaty, while not restricting the types of peaceful activities that may be conducted in Antarctica, emphasizes the importance of scientific research. It specifically provides for freedom of scientific investigation (Article II) and requires, to the greatest extent feasible and practicable, free exchange of plans for scientific programs, personnel, and observations and research results (Article III).

Third, the Treaty does not attempt a final resolution of territorial claims, but puts the issue on hold. It allows activities to take place in Antarctica without prejudicing the legal positions of any of the Parties. Article IV in essence preserves the status quo by providing that: (a) nothing in the Treaty itself shall be interpreted as affecting the legal position of any Party, (b) no activity by a Party shall constitute a basis for "asserting, supporting or denying a claim ... or create any rights of sovereignty in Antarctica," and (c) no new claim or enlargement of an existing claim may be asserted while the Treaty is in force. To minimize the risk of conflict, observers and scientific personnel are subject only to the jurisdiction of their state of nationality (Article VIII(1)).

The governance mechanisms in the Antarctic Treaty are highly decentralized. The Treaty does not establish a separate organization with international personality, or even any permanent secretariat (although it seems likely that a secretariat will be established in the near future). It requires consensus decisionmaking (that is, unanimous approval), rather than the two-thirds or three-quarters majority voting rule found in many other international, especially environmental, agreements. It does not provide for multilateral inspections. Finally, while the Treaty requires Parties to seek to resolve disputes by peaceful means, it does not require compulsory, third-party dispute settlement.

Instead of establishing a centralized institutional structure, the Antarctic Treaty provides for governance through periodic consultative meetings of the Parties and other, informal arrangements. This functional, pragmatic orientation has proved remarkably effective in practice.

-

Participation. The Treaty establishes essentially a two-tiered system of participation. The original 12 Parties, together with other Parties qualified

-

as ATCPs, are entitled to participate at meetings with full voting rights. Since the Treaty came into force, the number of ATCPs has more than doubled, from 12 to 26.3 An additional 15 nations that do not meet the activities requirement have acceded to the Treaty and may take part in meetings, but do not have the right to vote.4 These states are often referred to as non-consultative parties or simply contracting parties.

-

Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings. Meetings of the ATCPs are called Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (ATCMs). The Treaty does not specify the frequency of ATCMs. Since it came into force in 1961, 17 ATCMs have been held, approximately one every two years. Beginning in 1994, ATCMs will be held yearly. In addition to the ATCMs themselves, numerous preparatory, expert, and special consultative meetings have been held. Collectively these meetings have been called a semi-permanent conference of the parties.5

-

Decisionmaking. The Treaty provides that the Parties may adopt additional measures "in furtherance of the principles and objectives of the Treaty" (Article IX(1)). Despite the consensus rule, more than 200 such measures have been adopted, on subjects ranging from environmental protection to tourism to the preservation of historic sites and monuments. Recommendations adopted by ATCMs become effective when accepted by all Parties with consultative status at the time the recommendation was adopted.

-

Inspections. As indicated above, an ATCP may monitor another Party's compliance with the Treaty by means of national inspections. To date, there is no precedent for joint or collective international inspections.

-

Secretariat. Secretariat functions for ATCMs are provided by the host country. Although the Treaty does not establish an international organization, the adoption of the Environmental Protocol has stimulated plans to establish a secretariat, most likely within the next several years.

-

Dispute settlement. Disputes may be referred by mutual consent to the International Court of Justice, but this has never occurred.

Environmental Protection

The Antarctic Treaty prohibits nuclear explosions and disposal of radioactive wastes in Antarctica, but contains no other specific obligations to protect the antarctic environment. This reflects the fact that in 1959, when the Treaty was adopted, environmental protection was not a major focus. Nevertheless, the Treaty has provided a vehicle for the development of an extensive body of environmental regulation, by authorizing the Consultative Parties to adopt measures on "preservation and conservation of living resources in Antarctica" (Article IX). Under this authority, the ATCPs have adopted more than 100 environmental ATCM Recommendations:

-

The Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora (adopted in 1964, entered into force in 1978). The measures prohibit the killing, wounding, capturing, or molesting of native mammals or birds, except under a permit; require Parties to take appropriate measures to minimize harmful interference with the normal living conditions of native mammals or birds; establish a system of Specially Protected Areas (SPAs); prohibit the introduction of nonnative species; and designate a number of specially protected species. In 1975, the ATCPs adopted additional recommendations providing for the designation of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) (ATCM Recommendations VIII-3, VIII-4).

-

The Code of Conduct for Antarctic Expeditions and Station Activities (ATCM Recommendation VIII-11, 1975). The code includes recommended waste disposal procedures, which were thoroughly revised and strengthened in 1989 (ATCM Recommendation XV-3).

-

Environmental impact assessment guidelines (ATCM Recommendation XIV-2, 1987). The guidelines recommend preparation of a comprehensive environmental evaluation for activities likely to have more than a minor or transitory effect on the antarctic environment.

In addition to these recommendations are the conventions on seals and on marine living resources. CCAMLR is particularly significant in using an ecosystem approach, applicable to the entire area south of the Antarctic Convergence (which includes areas north of 60 degrees south latitude, outside the original Antarctic Treaty area); establishing the first permanent body under the Antarctic Treaty System, a secretariat headquartered in Hobart, Tasmania; and establishing a commission and a scientific committee.

Implementation by the United States

The Antarctic Treaty is implemented by the United States through an interagency process. Presidential Memorandum 6646, dated February 5, 1982, makes the National Science Foundation (NSF) responsible for overall Management of the U.S. Antarctic Program including logistic support so that the program can be managed as a single package.6 The Department of State represents the United States at ATCMs and other international negotiations concerning Antarctica. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) manages the United States' participation in CCAMLR.

The Antarctic Conservation Act7 is the principal environmental statute governing U.S. activities in the Antarctic. It gives NSF a broad mandate to control essentially all forms of pollution by U.S. citizens in Antarctica and implements the 1964 Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora. In addition, the Antarctic Protection Act of 19908 imposes a moratorium on U.S. mineral resource activities in Antarctica. Marine pollution in Antarctica is regulated under the Ocean Dumping Act9 (administered by the Environmental Protection Agency) and the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships10 (administered by the Coast Guard).

THE PROTOCOL ON ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION

The Antarctic Treaty did not attempt to address questions relating to the development of mineral resources, in part because commercial exploitation still seemed remote in 1959 and in part because of its highly controversial nature. The oil price shocks of the 1970s and the stirrings of commercial interest in prospecting in Antarctica led to discussions about developing a minerals regime. Between 1982 and 1998, the states negotiated the Conven

tion on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resources Activities, which was opened for signature on June 2, 1988, but is not in force.

The Protocol on Environmental Protection was developed in reaction to CRAMRA. Although CRAMRA contained stringent environmental safeguards, many environmentalists argued that, as a matter of principle, Antarctica should be left in its pristine state rather than be opened to mineral exploitation. In May and June 1989, two ATCPs—Australia and France—announced their opposition to the convention and proposed instead that Antarctica be designated a world park or wilderness reserve. This proposal gained support from other ATCPs and, in October 1989, the 16th ATCM decided to convene a special consultative meeting to consider the development of "a comprehensive system for the protection of the Antarctic environment." Initially some states proposed that comprehensive measures could be adopted through the Antarctic Treaty consultative process, while others supported the development of a freestanding environmental convention. Ultimately the ATCPs decided to negotiate a protocol to the Antarctic Treaty. The negotiations began at the special consultative meeting in Viña del Mar, Chile, in November and December 1990, and concluded with the adoption of the Protocol in Madrid on October 4, 1991. The Protocol requires ratification by all 26 of the current ATCPs to take effect. On February 14, 1992, the President sent the Protocol to the Senate which gave its consent on October 7, 1992. Because the Protocol is not self-executing, it will require implementing legislation to be given domestic legal effect by the United States.

Provisions

The Protocol on Environmental Protection extends and improves the Antarctic Treaty's effectiveness in ensuring the protection of the antarctic environment. It designates Antarctica "a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science." It sets forth a comprehensive regime, applicable to all human activities on the continent, including tourism. When it takes effect, the Protocol will replace the collection of measures adopted under the Antarctic Treaty consultative process.

As a protocol to the Treaty, rather than a freestanding agreement, the Protocol is governed by the general provisions of the Antarctic Treaty (Environmental Protocol Article 4). It applies to activities by Parties and their nationals; moreover, under Article X of the Treaty, Parties have an obligation "to exert appropriate efforts, consistent with the charter of the United Nations, to the end that no one engages in any activity in Antarctica contrary to the principles and purposes of the ... Treaty." In contrast to CCAMLR, which applies to the area south of the Antarctic Convergence, the Protocol applies only to the Antarctic Treaty Area—that is, the area south of 60 degrees south

latitude (Article 1(b)). Protocol parties will make decisions at ATCMs under the procedures in Article IX of the Treaty (Article 10), rather than through a new commission. Inspections are to use the observer system provided for in Article VII of the Treaty (Article 14).

General Governance Arrangements

The Protocol is perhaps more important for the general governance system it establishes than for the specific measures in its Annexes, which largely track existing recommendations adopted through the Antarctic Treaty consultative process. The main elements of the Protocol's governance system include:

-

Environmental principles governing all activities in Antarctica (Article 3). These principles require that all activities be planned and conducted so as to limit adverse impacts on the antarctic environment and that activities be monitored regularly. Article 3 also provides that activities be planned and conducted "so as to accord priority to scientific research and to preserve the value of Antarctica as an area for the conduct of research."

-

Cooperation in the planning and conduct of activities and sharing of information (Article 6).

-

A prohibition on all mineral resource activities except scientific research (Article 7). This prohibition may not be amended, except by unanimous agreement, for at least 50 years after the Protocol takes effect. Thereafter, an amendment to lift the prohibition would require adoption by a majority of the Parties to the Protocol (including three quarters of the current ATCPs), ratification by three quarters of the ATCPs (including all of the current ATCPs), and an existing legal regime covering antarctic mineral activities (Article 25). To protect the position of the United States, which wished to keep open the possibility of minerals activities, the Protocol provides that, if an amendment is adopted but does take effect within three years thereafter, a Party may withdraw from the Protocol.

-

Environmental impact assessment procedures applicable to all activities for which advance notice is required under the Antarctic Treaty (Article 8).

-

Establishment of a Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP), composed of representatives of the Parties to the Protocol, to provide advice and formulate recommendations to the ATCMs in connection with implementation of the Protocol (in particular, on the effectiveness of measures taken under the Protocol and the need to update, strengthen, or otherwise improve such measures or take additional measures) (Articles 11 and 12). The Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) and the Scientific Committee for CCAMLR may participate as observers, along with other relevant scien-

-

tific, environmental, and technical organizations invited to participate. The CEP will meet in conjunction with and report to the ATCM.

-

Inspections by observers in accordance with Article VII of the Antarctic Treaty (Article 14).

-

Annual reports by the Parties on steps taken to implement the Protocol, including measures to ensure compliance (Article 17).

-

Compulsory and binding settlement of disputes over the interpretation or application of, and compliance with, the Protocol. Disputes will be settled by an Arbitral Tribunal unless both sides have accepted the competence of the International Court of Justice (Articles 18–20).11

-

Although the Protocol itself provides for amendments through the unanimous decisionmaking procedure set forth in Article IX of the Treaty, each of the five annexes to the Protocol provides that ATCPs are deemed to have accepted an amendment unless they notify the depositary (the United States) within one year.

A regime for assessing liability for damage arising from activities in the Antarctic Treaty area could not be adopted at the same time as the Protocol; instead, rules and procedures for assessing liability will be elaborated in a future annex (Article 16). The 17th ATCM decided to convene an expert legal group to conduct the negotiations.

Specific Environmental Rules

In addition to the general provisions of the Protocol, a system of annexes, which are an integral part of the Protocol, set forth more specific and detailed measures and rules. Four annexes were adopted concurrently with the Protocol and a fifth shortly thereafter. They cover environmental impact assessment, conservation of antarctic fauna and flora, waste disposal and management, prevention of marine pollution, and protected areas. These annexes are intended to consolidate, systematize, clarify, and fill gaps in the assorted environmental measures adopted under Article IX of the Antarctic Treaty, rather than to break new ground. Additional annexes may be adopted after the Protocol takes effect.

Environmental Impact Assessment. Annex I sets forth rules designed to give effect to the Protocol's obligation to assess the environmental impacts of

proposed activities in Antarctica. Activities are divided into one of three categories. Activities determined to have less than a minor or transitory impact may proceed without an environmental evaluation. Activities with a minor or transitory impact must have an Initial Environmental Evaluation (IEE). Activities with more than a minor or transitory impact require a Comprehensive Environmental Evaluation (CEE). The Annex does not include standards or procedures for determining categories for specific activities. Instead, it simply requires Parties to develop "appropriate national procedures" to evaluate the environmental impact of proposed activities on the continent.

In contrast to the environmental assessment procedures adopted in ATCM Recommendation XIV-2, Annex I of the Protocol:

-

Applies to all activities in Antarctica, both governmental and nongovernmental, that require advance notification under Article VII(5) of the Antarctic Treaty (including tourist expeditions). ATCM Recommendation XIV-2 applied only to scientific research programs and their associated logistic support facilities.

-

Provides for a waiting period to allow collective consideration of CEEs by the Committee for Environmental Protection and the ATCP. ATCPs, however, apparently cannot veto a national decision to proceed with an activity.

-

Requires that CEEs be made publicly available, thereby allowing comment by interested nongovernmental organizations.

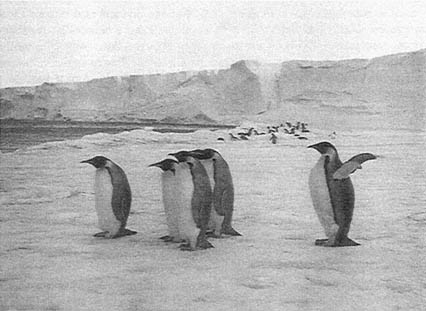

Antarctic Fauna and Flora. Annex II strengthens and updates the system of protection of native fauna and flora developed under the Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora. The Annex prohibits the taking of species without a permit, which may be issued only for specific and limited reasons (e.g., to obtain specimens for scientific study or for museums). Taking includes killing, injuring, capturing, handling, or molesting a native animal or bird. The Annex also prohibits, except under a permit, harmful interference with native species, such as those in Figure 3.1, and the introduction of nonnative species. The Annex builds on the Agreed Measures by providing protection for plants as well as mammals and birds. Prohibited takings include removing or damaging native plants in amounts that would significantly affect their local distribution or abundance. Moreover, any activity that results in significant adverse modification of plant habitats constitutes harmful interference. The Annex also goes beyond the agreed measures by (a) prohibiting harmful interference, rather than simply requiring "appropriate measures to minimize" such interference, and (b) requiring the removal of dogs by April 1, 1994.

FIGURE 3.1 Emperor penguins in the foreground with adelie penguins in the background, on sea ice that has frozen in front of the Ross ice shelf. (Courtesy of D. Siniff, University of Minnesota).

Waste Disposal. Annex III sets forth requirements relating to generation and disposal of wastes in the Antarctic Treaty area and is applicable to all activities for which advance notice is required under the Antarctic Treaty. The Annex is similar in design and content to the waste disposal procedures of ATCM Recommendation XV-3, which were adopted in 1989 but are not yet in force. In general, the Annex obligates Parties to reduce the disposal of wastes "as far as practicable to minimize the impact on the Antarctic environment" and to remove wastes from Antarctica if possible. Like ATCM Recommendation XV-3, Annex III classifies wastes into several categories:

-

Wastes that must be removed from the Antarctic Treaty area (including radioactive materials, batteries, liquid and solid fuels, and wastes containing harmful levels of heavy metals or acutely toxic or harmful persistent compounds).

-

Wastes that may be incinerated (other combustible wastes).

-

Wastes that may be disposed of in the sea (i.e., sewage and domestic liquid wastes).

It requires removal of some wastes that could be incinerated under ATCM Recommendation XV-3, including polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and most other

plastic wastes, and requires elimination of open burning of wastes no later than the 1998–99 season. In virtually all other respects, Annex III tracks ATCM Recommendation XV-3. Other requirements of the Annex include:

-

Identification and cleanup by the responsible parties of past and present waste disposal sites on land and most abandoned work sites.

-

Development of a waste management plan, to be updated annually and circulated to other Parties.

Marine Pollution. Annex IV obligates each Party to apply strict controls on ships entitled to fly its flag and to any other ship (with the exception noted below) engaged in or supporting its antarctic operations while operating in the Antarctic Treaty area. The Annex obligates Parties to adopt measures prohibiting discharge of certain materials from such ships. These materials include oil and oil mixtures; any noxious liquid substance, or any other chemical or other substance, in quantities or concentrations that are harmful to the marine environment; all plastics; and all garbage. Sewage may not be disposed of within 12 nautical miles (22.2 km) of land or ice shelves, but may be disposed of from moving vessels. Food wastes may be disposed of at least 12 nautical miles (22.2 km) from land or the nearest ice shelf, after being passed through a comminuter or grinder. These provisions largely track those in the amended International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL 73/78), and incorporate some of MARPOL's provisions by reference.

Annex IV does not apply, as legal matter, to vessels owned or operated by a state and used only on governmental, noncommercial service, although each party must take appropriate measures to ensure that such ships act consistently with the Annex, insofar as is reasonable and practicable. The Council of Managers of Antarctic Programs (COMNAP) has voluntarily adopted guidelines on oil spill prevention and cleanup, and all national operators have agreed to develop oil spill contingency plans for all stations and ships in 1993.

Specially Protected Areas. Annex V was negotiated after Annexes I-IV. It was adopted on October 17,1991, by ATCM Recommendation XVI-10 of the 16th ATCM. It is designed to simplify, improve, and extend the system of protected areas that has evolved within the Antarctic Treaty System under the Agreed Measures for the Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora. It provides for designation by ATCMs of two types of areas:

-

Antarctic Specially Protected Areas: areas with outstanding environmental, scientific, historic, aesthetic, or wilderness values. Areas designated SPAs or Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs) by past ATCMs will automatically become Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs) under the Protocol.

-

Antarctic Specially Managed Areas: any area where activities are or may be conducted may be designated an Antarctic Specially Managed Area (ASMA), to assist in planning and coordinating activities, avoiding possible conflicts, improving cooperation, or minimizing environmental impacts.

Management plans are required for both ASPAs and ASMAs, and are to be adopted by a decision of the ATCM. A permit is required to enter ASPAs, but not ASMAs.

How the Protocol Links Science and Stewardship

The concept of stewardship is embodied in Article 3 of the Protocol, with the five Annexes providing detailed rules for some aspects of environmental protection. The different approaches in the implementing legislation under consideration are to consider: (1) the general principles in Article 3 and the Annexes binding and enforceable, or (2) the Annexes binding and enforceable and the general principles in Article 3 as guidance. This raises the question: how complete are the Annexes in providing for stewardship? The Annexes address certain specific aspects of stewardship of Antarctica—environmental impact assessment, protection of flora and fauna, regulation of waste on land and at sea, and ways to limit visitation to certain areas—but they do not purport to be comprehensive. As in many other international agreements, the use of annexes allows problems to be addressed incrementally. If in the future, additional rules are deemed appropriate for other types of activities in Antarctica, the Protocol provides for the adoption of additional annexes. In contrast, Article 3 sets forth general principles of stewardship that apply comprehensively. The Protocol embodies the stewardship concept sufficiently, but the Annexes by themselves do not.

Challenges

The conclusion of the Protocol and proposed enactment by the United States of implementing legislation pose both an opportunity and challenge for the U.S. scientific program in Antarctica. By further protecting the antarctic environment, the Protocol will help preserve the unique opportunities the continent offers for scientific research of global significance. But it may also impose additional demands on scientists that affect the conduct of research in Antarctica.

The Protocol juxtaposes two sometimes complementary, sometimes competitive principles: environmental protection and scientific research. On the

one hand, it gives ''priority to scientific research'' (Article 3(3)). On the other hand, it requires that research be planned and conducted so as to "limit adverse impacts on the Antarctic environment and dependent and associated ecosystems" (Article 3(2)); further, it calls for the modification, suspension or cancellation of any activity that is found to threaten or result in impacts inconsistent with its environmental principles (Article 3(4)(b)). In implementing the Protocol, the challenge will be to conduct research programs of the highest quality possible, while minimizing adverse impacts on the antarctic environment.

Specific issues raised by the implementation of the Protocol and related to science include the following:

Administrative burdens. The Protocol will be implemented in part through environmental review and permitting requirements. Unless these requirements are designed in a user-friendly manner, they could significantly delay and increase the costs of scientific research.

The nature of environmental impacts. At the extreme, any human presence or activity corrupts the antarctic environment and disturbs the region's status as a natural reserve. The Protocol attempts to avoid this extreme by generally focusing on significant adverse effects (Article 3(2)(b)). But since it provides no objective measures of significance, such a determination will often be in the eye of the beholder. A specific example is that many scientific activities in the Antarctic, including some that are critical to Protocol objectives, require the use, deployment, and nonretrieval of materials that are not indigenous to the continent (see Box 1.2). Significance must be judged in a common sense, pragmatic way to ensure an appropriate balance among environmental and research needs and the associated benefits.

Limited information. The Protocol calls for the planning and conduct of activities in the Antarctic Treaty area "on the basis of information sufficient to allow prior assessment of, and informed judgments about their possible impacts" that "take full account of the scope and ... cumulative impacts of the activity" (Article 3(2)(c)(i)–(ii)). In many cases, however, information relating to a particular planned activity is limited or indirect. Strict or rigid definition of sufficient information could lead to the imposition of prolonged information-gathering studies that prevent more valuable scientific activity and indeed have greater cumulative environmental impacts. The challenge will be to ensure that the sufficient information requirement is applied pragmatically, weighing the value against the potential environmental harm of proposed activities, and not used to block activities or impose unwarranted data gathering programs.

Preemption of other research. Implementation of the Protocol will add to the cost of antarctic research because of the need to monitor activities in scientifically rigorous ways. Care will have to be taken to ensure that, insofar

as feasible, peer-reviewed research that is not directly applicable to implementation of the Protocol does not become excluded from the Antarctic. Research in several scientific disciplines is uniquely facilitated in Antarctica. The results can contribute to major advances, both in theoretical understanding and knowledge in the disciplines themselves and in more practical realms, such as the monitoring of space weather. Rigid application of Protocol-specific priorities could stifle basic research and its applications in several areas. A major challenge in implementing the Protocol will be to ensure the continuance of research in both existing and new areas whose relevance to Protocol concerns is not readily apparent at the time.

Environmental monitoring. Implementation of the Protocol will require, in particular, monitoring of environmental parameters. A major challenge will be to ensure that planning and execution of these monitoring activities are subjected to rigorous scientific peer review to ensure that they are indeed contributing to Protocol-related issues. The methods and instrumentation used should be state-of-the-art, and the activities should be designed to produce results that constitute a credible contribution to the scientific data base.

Consideration of scientific views. In setting U.S. policy, active scientists should be involved in both national and international groups, such as the Interagency Antarctic Policy Group and the Committee for Environmental Protection, as well as in advisory groups to these bodies, such as the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR). Those participating should have broad experience and be able to draw on their respective scientific communities at large.