4

Implementation of the Environmental Protocol

"The Devil", as they say, "is in the details." The previous chapters of this report have discussed the background of the Protocol and the challenge of balancing the equally important goals of good science and good environmental stewardship. In becoming a party to the Protocol, a state undertakes to fully implement its provisions. For the United States, implementation will involve a combination of federal legislation and regulation. These implementing documents will determine the conditions in which U.S. science will be done in the Antarctic. The challenge for the legislators and regulators will be to craft these documents so that the dual goals of advancing science and stewardship are achieved. This chapter outlines the most serious concerns expressed about the implementing process and its outcomes and makes recommendations that the Committee believes will best accomplish the goals of the Protocol.

ENVIRONMENTALLY RESPONSIBLE AND SCIENCE-FRIENDLY LEGISLATION

Antarctica is a remote place. Even by today's standards, to work in or visit Antarctica requires extra commitment and effort. Most antarctic scientists share the Protocol's commitment to protection of the antarctic environment and support effective implementation of the Protocol's goals. As the Antarctic Treaty provides and the Protocol specifically recognizes, a primary purpose of human presence on the continent is the advancement of science. Consequently, it is important that both the principles and the specifics of implementation be based on a balancing and integration of these two goals.

Many antarctic scientists have concerns, however, that the journey through the bureaucracy of required forms and approval loops may become figuratively more arduous than the journey to the continent itself. To avoid this and other potential pitfalls, implementation must be carried out with an appreciation of

the practical context in which science is actually conducted in Antarctica. Specific requirements must be measured not only by their adherence to the Protocol, but also by their impact on the ability of researchers to conduct not just science, but the best science.

What, then, do environmentally-responsible and science-friendly mean in this context? Clearly, individual scientists will differ according to their situations, needs, and problems; the conditions and sensitivities of various locations in Antarctica will differ in their need for protection. The Committee believes the development of implementing legislation and regulations should be guided by the characteristics of clarity, flexibility, simplicity, and practicability as described below. The Committee recognizes that other examples of legislative and regulatory programs attempt to achieve similar balances and may help inform the debate on how to best implement the Protocol. Several of these are discussed in Box 4.1.

Clarity

The language of implementing legislation and regulations should make clear to reasonable persons exactly what is required of scientists and, indeed, everyone visiting or working in Antarctica. Conditions and actions required before, during, and after deployment should be set forth clearly, and the agencies responsible for approving each step should be identified. In aid of clarity, terms used in the Protocol and in legislation or regulation, such as "minor or transitory," must be defined in a way that maximizes the commonality of interpretation of these terms by agencies and the scientists they support, as well as those engaged in nonscientific activities.

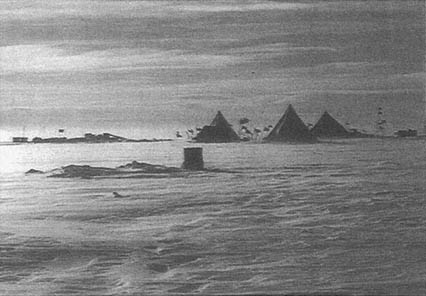

The Protocol's goal of preserving and enhancing the protection of the antarctic environment demands that scientists in the field be guided in their expected courses of action in potentially environmentally damaging situations. However, the reality of Antarctica for remote field camps, such as the one shown in Figure 4.1, is that scientists and on-site support personnel will not always have the opportunity to consult with authorities at home base before making certain decisions, particularly in emergency situations.

Flexibility

The legislation also should allow for flexibility—it should recognize that different levels of regulation may be appropriate for different activities in Antarctica. Generally, logistic operations and infrastructure have the greatest impact on the antarctic environment and should be subject to stricter environ-

|

BOX 4.1 LESSONS FROM OTHER MODELS Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources The Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), which is part of the Antarctic Treaty System, took effect in 1982 and is concerned with management of biological resources (excepting seals and whales) that might be harvested commercially. The focus of CCAMLR is on ecosystem management as a system, not as individual elements. For example, CCAMLR requires that no harvested species be allowed to diminish below a level that will have a significant detrimental effect on other species of the ecosystem. The CCAMLR process involves both a Commission (the decisionmaking body) and a Scientific Committee (an advisory body to the Commission). A secretariat in Hobart, Tasmania, attends to the day-to-day activities of the Commission and Scientific Committee and handles other functions, such as maintaining an extensive database on the status of various species within the ecosystem. It is clear that the intent of CCAMLR was to prevent significant disturbance of the biota of the antarctic marine ecosystem by commercial exploitation. The ecosystem approach, which is based on scientific understanding, is new to fisheries agreements. The continuing challenge for CCAMLR, and hence its lesson for the Protocol, is that such a comprehensive approach is complex and difficult. CCAMLR's goals, while environmentally desirable, have been difficult to attain because of the difficulty of defining the terms set forth with scientific rigor and ensuring compliance. Marine Mammal Commission In 1972, the Congress enacted the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), which sets aside marine mammals as a special group and puts their husbandry under federal control. This legislation established a permitting process for citizens (including scientists) who wished to take (capture, even if only briefly, or kill) a marine mammal. The legislation also created the Marine Mammal Commission (MMC), appointed by the President, and a Scientific Committee (an advisory body to the Commission) appointed by the Chairman of the Commission. The Commission has a full-time Executive Director and a staff to see to day-to-day activities. |

|

The implementation of the MMPA has direct parallels to the provisions of the Environmental Protocol, including overview by a scientific body, procedures for ensuring timely review and processing of permits, and a process for ensuring compliance with issued permits. Other Models Other areas of science provide models as well. The experience of the National Institutes of Health and the scientific community in establishing the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee to oversee recombinant DNA research can inform the debate over the benefits of a transparent process and the importance of basing regulatory control of scientific activities on the best and most current scientific information about the risks of the regulated activities. |

FIGURE 4.1 Remote field camp on ice stream, West Antarctica. (Courtesy of R. Bindschadler, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center).

mental review. Most research projects have lesser impact on the environment and may not require as stringent a review.

Science in Antarctica requires flexible approaches for several additional reasons. First, like all science, antarctic science focuses on the unknown, and the investigator cannot know for certain where the research may lead nor precisely how it will be conducted as it evolves. Second, the difficult conditions in which research in Antarctica must often proceed may give rise to unanticipated problems or situations. As a result, mandated procedures should be sufficiently flexible to allow scientists to make reasonable modifications to their programs, to respond to the different ways in which science is conducted on the continent, and, most importantly, to respond to emergency situations.

The Committee recognizes that striking an appropriate balance between flexibility and clarity is a difficult task. Achieving that balance, however, will be crucial to the effective linkage of the goals of environmental stewardship and conduct of good science.

Simplicity

Scientists should not be required to obtain multiple permits from multiple agencies. Usually the scientist is supported by a grant from one agency. This same agency should be the single point of contact for the scientist. If interagency communication is required, it should be handled by the agencies involved, not by the individual scientist. Permit procedures should minimize paperwork and speed decisions, so that scientists know whether approval has been secured before the preparations for their field work are well advanced.

Practicability

Both the nonroutine nature of research and the uniqueness of the environment raise important issues for the development and implementation of effective regulatory schemes for activities in Antarctica. For example, elements of the antarctic environment can be expected to respond differently to disturbance by human activities than environments in more temperate regions. Legislative and regulatory schemes should be practicable for application in the antarctic environment and should be effective in achieving the environmental protection goals of the Protocol.

ISSUES FOR IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ENVIRONMENTAL PROTOCOL AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR RESOLUTION

Many issues about the structure of the implementing legislation have been identified by those whose highest priority is the conduct of science as well as by those whose highest priority is protection of the antarctic environment. These groups are concerned that the outcome be neither too strict nor too lenient. The Protocol itself gives a high priority to scientific endeavors. It must be recognized that compromises will be necessary to make any legislation practicable and to ensure that the outcome supports both antarctic science and environmental protection. The legislation should recognize and incorporate the dynamic feedback cycle discussed in Chapter 1 by ensuring that the interactions between science and environmental stewardship are positive and mutually reinforcing.

Process versus Substantive Rules

As a first-order issue, the Congress and agencies of the executive branch responsible for the implementation process must decide on the appropriate balance among legislation, regulation, and case-by-case decisionmaking. Legislation often delegates the responsibility for more specific guidance to the regulation writing process.

Consider, for example, the determination of which impacts are "significant" under Article 3 of the Protocol or "more than minor or transitory" under Article 8 and Annex I. Congress could attempt to define these terms precisely in the legislation itself by enumerating, at the extreme, every specific impact deemed ''significant" or "more than minor or transitory." On the other hand, Congress could craft the legislation to establish a decisionmaking process that delegates to an agency or group of agencies the authority to determine whether an impact is "significant" or ''more than minor or transitory," either through rulemaking or case-by-case. The former approach maximizes legislative control over the ultimate results, but at the expense of flexibility to respond to now-unknown activities or new information on known activities. The latter approach is more flexible, but increases the possibility of overbroad exercise of agency discretion.

Inevitably, the implementing legislation will involve a mix of substantive rules and establishment of new processes. It would be impossible for the legislation to address fully every question on the implementation of the Protocol. More importantly, the Protocol, like the Antarctic Treaty itself, is intended to be a flexible instrument that can be amended relatively easily in response to new information or the demands of good science and good stewardship. Thus, the Protocol itself points the way to implementing legislation

establishing flexible processes that can accommodate changes in the Protocol without the need to amend the legislation each time.

A point of controversy that has emerged in discussions of the Protocol's implementation is whether Article 3, Environmental Principles, imposes substantive legal obligations, over and above the more specific rules in the Annexes. The Committee believes that Article 3 embodies principles of stewardship that go beyond the specific rules and procedures in the Annexes. Therefore, in becoming a party to the Protocol, the United States should seek to implement fully the principles of Article 3, including those concerning the decisionmaking process for permitting particular activities in Antarctica. Implementing legislation should recognize and incorporate the environmental principles of the Protocol (Article 3) so that agencies will be directed firmly along their administrative pathways. At the same time, however, these principles should be seen as too general to create specific legal requirements for individuals acting in Antarctica in the absence of some process or duty otherwise imposed by the legislation.

Article 3 requires that activities be planned and conducted on the basis of "sufficient information" about environmental impacts. In deciding whether to proceed with an activity, this requirement should be applied in a commonsense manner, using information that is available or can reasonably be obtained, not information that could conceivably be obtained with substantial additional study. Science is a priority activity that should, in general, be allowed, except in those circumstances where there is good reason to believe that the research proposed might cause unacceptable environmental impacts. This circumstance can exist when the weight of evidence is negative or when there simply is not enough evidence to make a reasonable judgment.

Both Congress and federal agencies, in implementing the Protocol, should take Article 3 into account in framing the constraints to be placed on activities. Agencies must recognize that the principles in Article 3 have substantive content and that actions taken under the Annexes will be measured against those principles in assessing environmental impacts. The Committee believes that, once government authorization for specific activities is obtained, scientists and others pursuing those activities should be able to proceed without risk of being found in violation of Article 3 as long as they are carrying out procedures as approved by the relevant authorization. If such approved activities are somehow determined to, in fact, violate the Protocol, then that responsibility should rest with the authorizing agency.

Recommendation 1: As a guiding principle, implementing legislation and regulations should provide a process based on appropriate substantive requirements, such as those in Article 3 of the Environmental Protocol, rather than a prescription for meeting the requirements of the Protocol. The process should be balanced so as to provide flexibility as well as clarity for meeting requirements.

Committee for Environmental Protection

The Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP), established in Article 11, will have an important role in the international implementation of the Environmental Protocol. The primary functions of the CEP, as stated in Article 12, are "to provide advice and formulate recommendations to the Parties in connection with the implementation of the Protocol." Article 12 enumerates a number of topics on which the CEP is to provide advice, including environmental impact assessment procedures, means of minimizing or mitigating environmental impacts, and the need for scientific research (including environmental monitoring) related to the implementation of the Protocol. Article 12 also specifies that in carrying out its functions, the CEP "shall, as appropriate, consult with the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR), the Scientific Committee for the Conservation of Marine Living Resources (SCCMLR) and other relevant scientific, environmental and technical organizations." Article 11 also designates these committees and organizations as observers to the CEP.

Given the strong scientific component and significance of the CEP's charge, it is clearly important that its work be informed by the best available scientific information directly relevant to its charge. There are several mechanisms through which the input of the best available scientific information and expertise to the CEP could be ensured: (1) through the membership of the CEP itself, (2) through a formal science advisory structure, or (3) through a combination of the two mechanisms. While SCAR, SCCMLR, and other relevant scientific, environmental, and technical organizations have a wealth of scientific expertise, which in some cases may overlap extensively with that needed by the CEP, none of these entities has a formal mission specific to the implementation of the Protocol. A formal science advisory body to the CEP would have the CEP's functions central to its mission. When it comes to the judgment and interpretation of scientific information in the formulation of advice and recommendations to the ATCM, however, it will be important that the CEP have sufficient scientific expertise within its ranks to address the scientific complexities and uncertainties that often arise in issues concerning environmental systems. Scientific expertise within the ranks of the CEP would also provide an opportunity for developing deeper levels of common understanding of the topics to be addressed. A common basis of scientific understanding can provide a solid foundation on which to develop consensus in areas having controversial policy implications.

In the Committee's view, the membership of the CEP should embody sufficient scientific expertise to ably address the complex scientific issues with which it will be faced. The U.S. representative to the CEP should be capable of integrating both the technical and policy expertise needed to represent effectively U.S. interests, including science and environmental protection. In

addition, the U.S. Department of State should strongly encourage other Parties to appoint representatives having such expertise. Within the United States, the U.S. representative to the CEP should seek advice of broad scope from the scientific, environmental, and other interested parties on environmental issues.

The environmental impacts of nonscience activities, particularly tourism, are potentially important. The Committee believes the United States should encourage the CEP to consider the needs and impacts of such activities. In addition, representatives of tourism and other industries with antarctic interests should be given the opportunity to contribute to the CEP as observers, and consulted with by the CEP, to the same extent as scientific, environmental, and other technical organizations designated in Articles 11 and 12.

Ultimately, the effectiveness of the CEP and, indeed, of the Protocol will be determined by the interactions among the CEP, ATCPs, and ATCMs. The Committee believes that the potential for the CEP to carry out its functions effectively would be greatly enhanced by the development of mechanisms to ensure that the best available scientific information and expertise are available to the CEP.

Recommendation 2: The United States should encourage the CEP to establish a formal science advisory structure for itself, which would include representatives of all interested parties. The nation should select a representative to the CEP who has both technical and policy credentials, and should establish a national process for providing scientific and environmental advice to the CEP representative.

Monitoring

Monitoring activities are certain to increase with implementation of the Protocol. This certainty has raised concerns that not enough attention has yet been paid to the pitfalls inherent in the design of effective monitoring programs. Evidence from other programs (NRC, 1990) indicates that monitoring activities can be too narrow in scope or (and perhaps worse) overly broad and misdirected; these failings are often due in large part to lack of a sound scientific basis for program design, or a clear focus on important governance issues, or both.

Ideally, the design of a monitoring program should be based on the intended use of the resulting data—that is, the design should be driven by the program's objectives. The design also should be well matched with the dominant temporal and spatial scales of the physical, chemical, and biological processes that characterize the system being monitored. In the Antarctic an effective monitoring program would include the following objectives:

-

Understanding the dynamics and controlling processes of the major environments and ecosystems;

-

Determining the extent of contamination of antarctic environments associated with human activities in coastal areas and on the continent;

-

Tracking the exposure of the antarctic continent to globally distributed pollutants such as lead, mercury, and anthropogenic organic contaminants; and

-

Tracking the variation in atmospheric, glacial, and oceanic constituents that affect the global environment.

The first two objectives are directly related to stewardship of Antarctica; and over time, the first objective can provide a critical foundation for interpretation of the other monitoring data. Long-term monitoring data have perhaps been undervalued in the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP), in part because such data have not often been acquired with the kind of scientific rigor that has characterized much of the rest of antarctic research.

The National Science Foundation's support of two long-term ecological research sites in Antarctica has significantly advanced progress toward the first objective. Given the uncertainties in current understanding of climatic change and the importance of Antarctica to global climate, maintenance of monitoring networks in Antarctica will continue to be important.

Monitoring data collected to meet the objective of understanding the different systems would encompass, for example, weather data, hydrologic data, and data on biological processes. Hydrologic data might include velocity measurements of estuarine or oceanic currents, streamflow, lake levels, and glaciologic advance or retreat. Biological data might include population counts, species distribution, and plant or animal tissue concentrations of pollutants. The choice of parameters would depend on the specific issues to be addressed by the monitoring program. For a detailed discussion, see Benninghoff and Bonner (1985).

A monitoring program intended to meet the second objective should be designed as an early warning system. It would detect failure in the procedures for controlling new pollutant inputs or containing the spread of pollutants introduced into the environment during the initial establishment of bases decades ago. In this case, the strategy should be to evaluate the potential pollutants, and determine which ones could be most accurately and easily monitored to indicate contamination extending beyond accepted or known bounds. This strategy is very different from a shotgun approach which attempts to measure all priority pollutants at every site. That type of approach can waste large sums of money amassing measurements below detection limits and of little scientific value.

A monitoring program for the third objective could be based on regular but infrequent analysis at key sites for a broader range of contaminants that

potentially could be persistent and globally distributed. These analyses, even for compounds which are not detected, can be valuable in the future for documenting the appearance, fate, and cumulative impact of long-lived pollutants that occur in minute quantities. The selection of contaminants to be measured should also include widely used materials that are supposedly short-lived in the environment. The lesson from the discovery of atrazine in surface and ground waters in agricultural areas of the United States is that pollutants sometimes remain in the environment much longer than is predicted from laboratory experiments. Analyses of contaminants in ice cores and sediments from the monitoring stations would be an important aspect of an initial monitoring program.

Programs that address the fourth objective are already established. The ozone hole is now monitored and well-characterized every year. In addition, continuing research is aimed at gaining a better understanding of the physical and chemical processes that control the formation of the ozone hole. Continued evaluation will be necessary to determine whether and how additional characteristics and processes should be monitored.

Lastly, environmental monitoring associated with scientific research should not be a function passed on to the investigator unless it forms a component of the proposed scientific study. Nor should sponsoring agencies make extended monitoring of field experiments a requirement for funding them. Any such extended monitoring requirements should be provided for in a manner centrally coordinated among the agencies; funding for such requirements might be considered as monitoring overhead.

The agency or agencies charged with conducting an environmental monitoring program should design it to collect the most important data required for the four governance and stewardship objectives described above. In addition, U.S. monitoring should address the complex context of international governance issues. While science may not be the primary motivation for the development of a monitoring program, the information derived from the program will be of little value if it is not collected in a rigorous and scientifically sound manner. The Committee believes that the expertise of persons outside the agencies should be used in designing the monitoring programs, selecting instrumentation and techniques, and in periodic review, such as now occurs for all antarctic research activities.

The value of a monitoring program also depends upon a stable and effective institutional and administrative infrastructure. Two key elements of this infrastructure are data base management, and quality control and assurance. Data base management should make the data accessible in a timely manner to the U.S. public and to interested international parties. The quality control and assurance element is especially important to ensure the accuracy and the utility of the information and because of the international example set by the United States in its traditional leadership role in antarctic science.

Recommendation 3: Monitoring activities—both those under way and additional ones that will be needed to comply fully with the Protocol—should be directed to answer important national and international governance questions, and designed and conducted on the basis of sound scientific information with independent merit review.

Resources

Antarctic research is relatively resource-intensive because of the required logistic support (e.g., ships, planes, personnel). Implementation of the Protocol inevitably will bring additional costs for remediation and monitoring, meeting new requirements for environmental protection, which may, indeed, require more logistic support.

The Committee hopes the Executive Branch and the Congress recognize that additional costs associated with implementation of the Protocol are real, and that science and stewardship should not be constantly competing with each other for resources. However, the Committee also recognizes funding may not increase any antarctic activity and that, even in that case, it may be desirable to continue U.S. antarctic research at least at its current level. If trade-offs are necessary, their impact on science is a question of great concern to antarctic scientists. For example, it has been alleged that increased emphasis on monitoring will reduce resources for more traditional antarctic science. In the Committee's view, this is not the optimum path to either good science or good environmental stewardship.

The Committee believes that all aspects of the USAP—science, logistics, and activities resulting from the Protocol—should be conducted in the most efficient way possible. This is particularly true of logistics, which currently represent about 90 percent of the total expenditures for the USAP. For example, the number of support personnel, either civilian contractors or military personnel, should be carefully reexamined each year. Such a review should also include guests of the USAP. Aircraft and ship support (e.g., number of flights, crew size, number of days on station) should be examined with regard to the utility to overall support requirements and the science program. In recent years, NSF has been considering the balance between military and civilian support contractors, and has been shifting toward greater use of civilian support contractors. It seems prudent for NSF to continue to reevaluate the appropriate balance of contractors with particular emphasis on cost-effectiveness.

Recommendation 4: Where more efficient operational modes can be identified, they should be implemented quickly and the savings applied to the conduct of science and to meeting the needs of the Protocol.

Who's in Charge—Scientific and Nonscientific Activities

The Protocol does not suggest how governments should organize internally to discharge the duties and responsibilities created by the new instrument. From nation to nation the assignment of internal roles and responsibilities for carrying out the requirements of the Protocol can be expected to differ widely depending on the range of national traditions, experience, and current circumstances.

The experience of the United States over the past 30 years provides a substantial base for addressing the organizational question. By current and previous Presidential and National Security directives (most recently, White House Memorandum 6646), NSF is the sole supporter of science and logistics in Antarctica under the aegis of the USAP. Some matters not solely of a research nature have been assigned to other agencies. For example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) was given responsibilities relating to enforcement of restrictions on minerals development under the Antarctic Protection Act, and the conservation of living resources under CCAMLR.

The support structure for science in Antarctica is vast and expensive. Each member of a scientific project is backed by about four support personnel, and the financial commitment for logistics is about ten-fold that for science. Support activities are controlled by NSF and executed by support contractors, the Department of Defense, or the Coast Guard. Although scientists are obligated to adhere to the environmentally sound use of these support services, the agencies providing the logistics support are ultimately accountable for hazards associated with their operations.

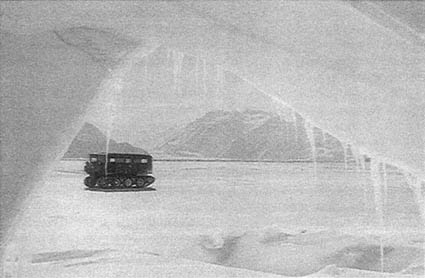

The major permanent bases—McMurdo, (Figure 4.2), South Pole, and Palmer Stations—are the backbone of the support infrastructure for U.S. science in Antarctica. These stations house laboratories, dormitories, cafeterias, waste disposal facilities, communications equipment, transportation and maintenance facilities, and a variety of other facilities necessary to operate the scientific program in Antarctica. Most U.S. research is conducted at or near these bases, and researchers rely on them for providing logistic support, such as by the tracked vehicle shown in Figure 4.3. Some antarctic research, particularly in glaciology and geology, is conducted in the deep field, at temporary camps that vary from 2 to 10 persons. Larger camps have limited support from full-time, on-site personnel; however, most are self-sufficient and receive little or no resupply during their terms of operation. All field camps are temporary, are populated for, at most, a few austral summers, and are removed at the completion of the project.

Logistic operations and infrastructure in support of research activities that have the greatest potential to adversely affect the environment. Most individual scientific projects would likely have small impact relative to, for

FIGURE 4.2 McMurdo Station, Antarctica. (Courtesy of National Science Foundation).

FIGURE 4.3 A tracked vehicle often used for traveling on annual sea ice close to antarctic bases. The view is taken out of an ice cave that commonly occurs in ice shelves around the antarctic continent. (Courtesy of R. Bindschadler, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center).

example, the construction and operation of a sewage treatment facility or a new residential facility to support science. Some requirements appropriate for activities at a major base may not be appropriate for those at a field camp. An across-the-board approach could be environmentally counterproductive if it entailed additional logistic support for small-scale activities. The Committee believes that the legislative and regulatory implementation of the Protocol should reflect the potential environmental impact of the proposed activities. In the Antarctic, it is useful to differentiate among several types of activities, including:

-

Scientific research: the conduct of the research itself (i.e., the specific experiments)

-

Logistics that support specific scientific research: the smaller scale activities associated with specific projects (e.g., helicopter flights, supply drops)

-

Large-scale logistics activities: the major base operations, including ships and transport aircraft

-

Nonscientific activities: primarily fishing and tourism and their support infrastructure.

The implementation of the Protocol requires the establishment of a process for determining the specific actions necessary to fulfill the obligations of the Protocol for the various types of antarctic activities, and for ensuring that those actions take place in an appropriate manner and are, in fact, meeting the obligations of the Protocol. This type of regulatory process has four components:

-

Rulemaking: establishing the specific terms and conditions by which activities will be regulated.

-

Decisionmaking: applying the rules to specific activities (i.e., reviewing and permitting projects and programs).

-

Compliance: assuring that rules are followed.

-

Monitoring: gathering and evaluating information on the condition of the environment that is being regulated.

In evaluating how these governance responsibilities, which the Committee believes will only grow more complex, should be applied to U.S. research activities in Antarctica, it considered the following factors:

-

Science will be at the core of antarctic activities for many years to come. Although a growing range of tourism, fisheries activities, and other, as yet unknown, pursuits will be attracted to Antarctica, the conduct of high quality science undoubtedly will be the major activity into the next century. Clearly, NSF will play a central role in the management of this science and the

-

associated logistics. However, the issues in Antarctica are now much broader than science.

-

A single lead agency can often yield significant benefits in efficiency. This appears to be particularly important in managing science. It is, unfortunately, characteristic of bureaucracies that every agency added to a regulatory approval scheme seems to increase the complexity (and attendant paperwork) and difficulty for the regulated parties logarithmically. Undue delay and bureaucracy, and the confusion and frustration that inevitably follow could drive good scientists away from antarctic research. Also, clear authority can be important. The prompt response by NSF to the wreck of the Bahia Paraiso at Palmer Station in 1989 may have been possible because it was clear who was in charge. A harsh environment like Antarctica's requires that the lines of authority be absolutely clear. On the other hand, agencies generally should not be tasked with regulating their own activities. No matter how good the intentions, the tendency to start looking the other way is almost inevitable. The incentives for self-regulating agencies to say ''yes'' in order to accomplish activities are greater than for such agencies to say "no" or "wait."

-

The near-pristine state of Antarctica is essential to its value as a place to conduct many types of scientific research. Antarctic science that reaches into space or attempts to explain global processes depends to a significant extent on the high quality of the natural environment. The fundamental importance of many of these research areas is perhaps better understood and appreciated than it was several decades ago. But doing the science cannot be allowed to unacceptably compromise the quality of the environment in which it is done. Resolving potential conflicts between research activities and environmental protection may now be too important to leave solely within the purview of scientists.

-

Society has come to value a high quality environment to a far greater extent than was the case 40 years ago, when NSF first supported and managed science in the Antarctic. In the United States, institutions and capacities have been created to address a range of environmental issues and assure appropriate protective and preventive actions are taken. The increasingly complex activities in Antarctica pose more complex governance questions, especially in relation to the environment. Therefore, it seems unwise not to take advantage of those institutions and capacities that exist throughout the federal government.

-

NSF does not easily support some kinds of science-based activities important to governance. Many of the decisions called for by the Protocol will require an enhanced, ongoing effort aimed at characterizing current conditions and monitoring their status. This type of effort is not traditional antarctic science (i.e., problem-oriented and investigator-initiated), nor is it the type of research NSF has been charged to support either programmatically or fiscally.

Yet environmental monitoring and characterization of environmental conditions must take place.

The Committee believes that NSF's performance in selecting, via merit review, the science to be done in the Antarctic has been exemplary. At the same time, the Committee recognizes that there have been problems with the management of other parts of the program—for example, long delays in adopting regulations based on existing statutes, which would have better protected the environment. NSF also has acknowledged these problems and is working to correct them.

The Committee believes implementation of the Protocol should establish a clearer mechanism for separating the responsibility for each of the types of antarctic activities discussed above. This mechanism would involve agencies in addition to NSF, as appropriate, in the governance of antarctic activities. The Committee recommends the following:

Recommendations 5a: The existing management relationship between the National Science Foundation and the research community should be essentially unchanged. That is, the current pattern of submittal of proposed research projects and their approval, funding and oversight, should remain intact, modified only as new scientific and environmental requirements might suggest.

Recommendation 5b: The National Science Foundation should be granted primary rulemaking authority necessary to implement the Protocol; however, when that authority involves matters for which other federal agencies have significant and relevant technical expertise (e.g., the Environmental Protection Agency for solid and liquid waste), the concurrence of those agencies must be sought and granted in a timely manner before a regulation is issued for public comment. The implementing legislation should identify, to the extent feasible, the specific instances and agencies where this would be the case.

Recommendation 5c: Decisions required under the implementing legislation and related compliance activities regarding major support facilities should reside with the federal agency that would normally make such decisions in the United States. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency would grant a permit to the National Science Foundation for a wastewater treatment facility and would conduct periodic inspections.

Recommendation 5d: A special group should be established to provide general oversight and review of:

-

proposals on the concept location, design, etc., of major U.S. logistic facilities, or significant alterations to existing facilities in Antarctica;

-

environmental monitoring activities; and

-

National Science Foundation program actions to ensure compliance by U.S. personnel (i.e., scientists and others supported by the government) as required by the Protocol and implementing legislation.

The Committee believes that this last responsibility is best vested in a group, not a single agency, of the federal government. One option would be to expand the scope of the Antarctic Policy Group of the National Security Council, perhaps via a standing committee, to include this responsibility. Such a group ideally should be composed of persons with scientific and technical expertise. In any case, this group should actively solicit scientific and technical information to inform its decisions.

The Committee believes that implementing these recommendations would keep NSF at the center of antarctic science and its specific governance, while taking greater advantage of the expertise of other agencies and sharing the burden of overall program management. At the same time, the Committee has proposed a process that would subject the major logistical and operational functions of the antarctic program to greater scrutiny. This process should help ensure that decisions on the national commitment and presence that major operational facilities represent will receive the appropriate level of review and oversight.

Environmental Assessments

The Environmental Protocol seeks to apply in Antarctica an environmental assessment process that is based in many ways on the procedures in the U.S. National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). It should be noted that recent Administrations have taken the strong view that NEPA did not apply outside the United States. However, a recent decision of the District of Columbia Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, Environmental Defense Fund vs. Walter E. Massey and the National Science Foundation , overturned a lower court ruling and endorsed the extension of NEPA and its Environmental Impact Statement process to NSF's activities in Antarctica.

It appears for two reasons, however, that simply reproducing NEPA in the Antarctic will not meet the requirements of the Protocol. First, NEPA defines a course of action to be taken after a determination of "significant" environmental impact. The Protocol, on the other hand, requires environmental evaluations for "minor or transitory" impacts, which presumably are less than the "significant" standard of NEPA. In addition, NEPA applies only to actions of the government or supported by the government, while the Protocol requires environmental evaluations of nongovernmental activities, such as tourism.

For the purpose of determining the level of environmental assessment required, Article 8 and Annex I of the Protocol together establish three categories of activities:

-

Activities determined to have "less than a minor or transitory impact" do not require environmental evaluation.

-

Activities likely to have a "minor or transitory impact" require an initial environmental evaluation (IEE).

-

Activities likely to have "more than a minor or transitory impact" require a comprehensive environmental evaluation (CEE).

Implementing Article 8 and Annex I will require decisions on the categories of specific proposed activities. However, the term "minor or transitory" impact has no clear or inherent meaning, and the Protocol gives no definition or specific threshold of severity or persistence of impact for determining the appropriate level of environmental assessment, if any. Consequently, scientists and administrators will need to exercise judgment to meet the dual goals of responsible stewardship and avoidance of unnecessary constraints on antarctic science. It should be noted that predictions of minor or transitory effects will necessarily be based on data, some of which will have greater associated uncertainty than others. Inevitably some predictions will not be correct. In cases where effects turn out to be greater than anticipated, there exists the potential for environmental harm. In cases where predictions overestimate the potential for adverse effects and an activity is not allowed to go forward, potentially valuable research opportunities may be lost.

The Committee believes Article 8 and Annex I are intended to ensure assessment of activities likely to significantly affect the antarctic environment, with significance reflecting both severity and persistence of impact. In the Committee's view, Article 8 and Annex I should be interpreted to that end. The Committee offers the following discussion in the expectation that it may provide useful guidance to administrators and others. The Committee does not offer this discussion as a basis for proscriptive language to be adopted in legislation.

Scientific and ecological considerations offer some guidance to the meaning of minor or transitory. An impact detectable with scientific instruments clearly could still be less than minor (e.g., such impacts may lie within natural variation). Further, it seems apparent that the spatial extent of the project relative to the scale of the system and the nature of the perturbation itself are key to determining whether an activity is minor. For example, the impact of thousands of research projects, all involved in sampling the same penguin colony, would not be minor or transitory, although the impact of any one or two of them likely would be.

The determination of whether an impact is transitory should be based on timescales for natural variation. For many ecosystems, annual cycles of light and dark are the dominant scale of natural variation. Where this is true, a impact that is expected to persist for more than one year following the cessation of the project would be more than transitory. The dominant scale of natural variation is tied to breeding cycles for other populations. In such cases, a prediction of recovery to previous levels within one generation time—the average age at which a female gives birth to her first offspring—would represent a less than transitory impact. However, in those ecosystems which are driven by long-term oceanic processes, decadal patterns of variation are common. In that circumstance, a recovery period of a decade or more may still represent a less than transitory impact.

Environmental assessment should be required for activities whose impact is likely to be either severe, but only temporary, or less severe, but long lasting. It seems clear that the USAP as a whole has had a major impact on the continent's environment. Thus, the Protocol would require an environmental assessment of the program and its associated logistics. However, the Committee believes that Article 8 and Annex I can reasonably be interpreted to exempt from individual environmental assessment an entire category of common activities of scientists that are likely to have only a slight or de minimis effect on the environment—for example, travel to various locations or research sites (Figure 4.4); collecting air, ice, water, or limited rock samples; setting up temporary camps and experimental equipment. Humans obviously exert some effect, albeit minimal, on the antarctic environment by simply being there. It cannot be the intent of the Protocol to require prior individual assessments for all such activities. Figure 4.5 illustrates the three levels of activity defined by the Protocol, viewed from the foregoing perspective.

Such a common sense approach would permit Article 8 and Annex I to be implemented so as to meet environmental objectives, but minimize unnecessary burdens and delays for antarctic scientists. In this regard, the Committee notes that it may be possible for administrators (and useful for scientists) to define in advance those broad types of common scientific activities that are considered to have de minimis , or "less than minor or transitory," impact and thus do not require environmental evaluation. It may also be possible for the administering agency to determine that broad classes of activities, or sheer numbers of projects, are in fact likely to have a minor or transitory impact and thus require an IEE. The agency could then conduct, with appropriate public involvement, such an evaluation on a blanket or categorical basis, establishing in advance the conditions and circumstances under which such activities can be conducted. We note that a high volume of activity, no matter how passive or limited in personnel, would likely exert more than a minor or transitory impact; these matters are probably best addressed by the administering agency in a blanket format for the program.

FIGURE 4.4 A researcher has traveled by snow mobile to a remote site in order to operate an electronic distance-measuring device on the ice sheet. Surveys of networks of such markers provide glaciologists data on the flow rates and deformation rates of the ice sheet. (Courtesy of R. Bindschadler, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center).

Actions of this type would help antarctic scientists plan their activities, reduce paperwork, and save time.

With foresight and an understanding of the practical context, the goal of environmental protection can be attained in a manner compatible with the most effective conduct of antarctic science. In the discussion that follows, we describe a hierarchy of categorization for antarctic science projects that addresses this goal. A first consideration is the level of logistic support required by individual projects. Support can be divided into logistics for camp facilities and logistic activity at the main bases, such as McMurdo, South Pole or Palmer stations, as shown in Ibble 4.1. The Committee believes that science projects that involve a new permanent facility or a major addition to an existing permanent facility and are operated for a sustained period (e.g., more than three seasons), would exert more than a minor or transitory impact and would require a CEE. At the other end of the spectrum, small field camps that involve only an incremental increase in overall main base activity should be considered to have impacts that are less than minor or transitory. The size of the field camps can be gauged by the requirement for full-time personnel to operate large equipment or for other camp activities.

It is clear that certain research activities, even when part of an individual project, must be viewed as more than minor or transitory and thus require a CEE. These include:

-

release of radioactive materials,

-

large-scale collection that would adversely affect populations of native flora and fauna beyond recovery within one generation time, and

-

release of compounds predicted to be environmentally damaging over long time scales as discussed above.

TABLE 4.1 Framework for environmental evaluation of logistic support requirements for individual science projects. (Courtesy of D. McKnight, U.S. Geological Survey).

|

Examples of Logistic Activities |

More than Minor or Transitory |

Minor or Transitory |

Less Than Minor or Transitory |

|

Logistics for camp facilities |

Permanent structures and full-time personnel for camp operations |

Large field camps with full-time personnel for camp operation |

Small field camps without full-time personnel for camp operation |

|

Logistic support |

Substantial and sustained |

Substantial |

Incremental |

Next, the Committee suggests that types of activities appropriately viewed as minor or transitory, requiring an IEE, include:

-

large field camps requiring full-time personnel for camp operation,

-

studies that require banding of large numbers of birds or mammals, and

-

medium-scale perturbation experiments such as rerouting waterflow or manipulating habitat of birds or mammals.

Finally, certain individual projects fall within neither of the categories above. These can be viewed as de minimis, or less than minor or transitory, and require no individual environmental assessment. NSF (1992b) presents the following list of research activities determined to have a less than minor or transitory impact:

-

low volume collection of biological or geologic specimens, provided no more mammals or birds are taken than can normally be replaced by natural reproduction in the following season;

-

small-scale detonation of explosives in connection with seismic research conducted in the continental interior of Antarctica where there will be no impact on native flora or fauna;

-

use of weather/research balloons, research rockets, and automatic weather stations that are to be retrieved (see Figure 4.6); and

-

use of radioisotopes, provided such use complies with applicable laws and regulations, and with NSF procedures for handling and disposing of radioisotopes.

The Committee's opinion is that the de minimis category should also include the following types of activities:

-

passive experiments that can be removed, such as remote sensing experiments;

-

small-scale perturbation experiments, such as ecological experiments that replicate natural processes;

-

release of trace quantities of naturally-occurring substances;

-

geologic sampling, surveying, and meteorite collection;

FIGURE 4.6 Retrieval of a balloon carrying automated experimental instrumentation. (Courtesy of R. Sanders, NOAA/ERL, Aeronomy Laboratory).

-

ice coring that does not require a fluid-filled hole and sediment coring that does not require drilling fluid or blowout preventers; and

-

experiments involving small diving teams in coastal areas or lakes.

Nongovernmental Activities. A sizeable increase in nongovernmental activities, most notably tourism, has occurred over the past decade, with the largest increase coming in the past seven years. For the past three seasons, it has been estimated that the number of tourists has annually exceeded the number of personnel involved in national scientific and logistic programs in the Antarctic. Tour operators who are members of the International Association of Antarctic Tour Operators have guidelines for educating passengers on their responsibilities under current U.S. law and for governing their own conduct (see Appendix A). However, up to now, the use and observance of these guidelines has not been mandatory.

The Protocol and its Annexes make it clear that the environmental protection process is meant to apply to private sector activities, such as tourism. Any activity that requires advance notification under Article 7 of the Treaty, including tourism, must abide by the principles in Article 3 of the Protocol, and regulations governing the actions of commercial tour operators must be implemented by each Antarctic Treaty Consultative Party (ATCP). Annex I requires tour operators to prepare initial and/or comprehensive environmental evaluations of their proposed activities; the issues are similar to those associated with assessing the impact of science and its support.

For example, should a few sites be identified as tourist destinations to which every operator would go and, hence, forgo visiting other areas of the continent? The likely result, over time, would be environmental degradation of these designated areas. Or should tour operators be required to limit the numbers of persons at any one site, but be permitted to visit a larger number of sites? The likely result in this case would be less intensive damage, but to more sites, some of which may be especially sensitive. The considerations here revolve around limiting the geographic extent of environmental damage, but allowing a major and persistent impact, or allowing a lesser impact over a larger geographic area.

Too little information is available on the environmental impacts of tourism to support specific decisions on the conduct or extent of such activities. The baseline data are incomplete and conclusive monitoring programs have not been completed. Sufficient scientific information to address these issues is a key priority created by the Protocol. In addressing these data needs, the environmental evaluations for nongovernmental activities must be specific enough to indicate explicitly the impact of such activities on science.

Timeliness

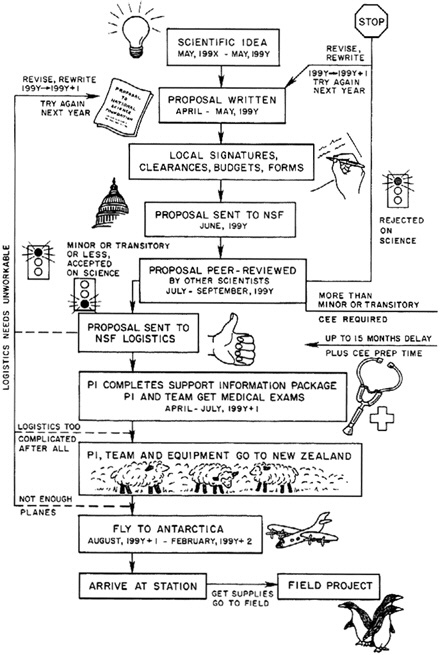

The path to conducting research in Antarctica is already long. Proposals to NSF for field research, for example, must be submitted at least 18 months in advance. This time is needed to allow for the merit review and selection process, and for the complexities of the logistic planning for projects selected. Effectively, scientists must propose future work before their current work is complete. Given the general dependence of next year's work on this year's results, it is often impossible to know exactly what experiments are called for two years in the future. Thus, it will often be difficult to specify the exact details of the field activities. Yet, to delay the approval process until the field season is at hand risks prohibiting investigators from conducting the research they were supported to perform.

Figure 4.7a shows the process through which a Principal Investigator (PI) must go from project conception to conduct of research in Antarctica. As the figure shows, it can take years from the time the PI develops an idea to the time the project is approved by NSF and gets under way in Antarctica.

Access to the Antarctic is limited to narrow windows of time during the austral summer—two to four months depending on the station. Implementing legislation may increase the time required for the approval process so as to create delays that could compromise the quality of some research projects. Delays of even a few months could result in actual delays of up to one year in research projects. If methods and equipment cannot be changed, it might not be possible to take advantage of recent technological advances. In addition, longer approval cycles might compromise scientists' abilities to respond quickly to unanticipated natural events.

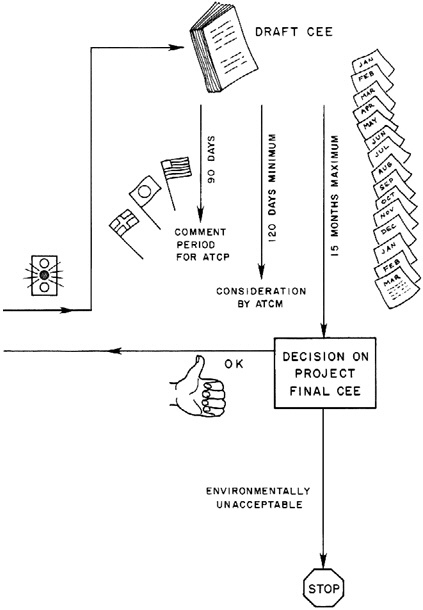

The Protocol specifies that only projects that may have more than a minor or transitory impact require a CEE and must be communicated by the ATCPs for consideration at the next ATCM. Figure 4.7b shows the steps of the CEE process required by the Protocol, and the time each step may take. Projects requiring a CEE could be delayed by up to 15 months. The Committee feels that the CEE requirement will affect few individual research projects and not encumber antarctic science.

Projects having a minor or transitory impact require the preparation of an initial environmental evaluation (IEE). Unlike CEEs, IEEs do not necessitate consideration at an ATCM. As shown on Figure 4.7a, the Committee envisions that the IEE process can be built into the existing timeline for the initiation and conduct of research in Antarctica. The review of IEEs for individual projects could occur at the same time the project is judged on

scientific merit, and thus not impose additional time requirements on the research planning process. However, if a process is established that subjects science projects determined to have only a minor or transitory environmental impact (i.e., requiring an IEE) to an approval process, delays could result in an adverse impact on the scientific goals of these projects. Thus, the committee recommends:

Recommendation 6: Legislation implementing the Protocol should not impose additional delays in the approval of scientific projects determined to have no more than a minor or transitory impact on the antarctic environment.

Transparency

From the beginning of the Antarctic Treaty System, transparency has been an important component of the governance system. Article 7 of the Treaty established the principles of open inspection and freedom of access, which were then entirely new concepts for regulating the international affairs of nations. For more than thirty years these mechanisms have assured adherence to the letter and spirit of the Treaty.

Earlier sections of this report note that these mechanisms have not always been sufficient to ensure that activities in Antarctica were conducted in a fashion that adequately protected the environment. As a result, during the 1980s, nongovernmental organizations expressed growing concern about conditions on the continent. These concerns were exemplified by:

-

establishment of a scientific research base and ship-based inspection by Greenpeace;

-

litigation by the Environmental Defense Fund and others;

-

development of the Visitor and Tour Operator Guidelines, and the creation of IAATO, to provide self-regulation of tourism activities; and

-

active participation in negotiation of international agreements, including the Protocol, by the World Wildlife Fund and others.

These actions by international nongovernmental organizations played an important role in highlighting environmental problems in Antarctica as well as in crafting the Environmental Protocol.

This recent experience suggests that it is important that the principles of openness and access in the governance of Antarctica be extended to the general public. The public has already demonstrated strong concern for the protection of the continent and an ability to translate that concern into meaningful participation in the international negotiating process. It is now

important to include the public in the process of governance that will begin with the implementation of the Protocol. The preservation and protection of Antarctica is best served by considering the views and employing the expertise of all interested parties.

The Committee strongly believes that one of the benefits of this inclusive approach is that it would enhance awareness of governance and its relation to the conduct of science in Antarctica. This awareness should contribute in the long-term to an increased sensitivity to the careful balance that must be struck between the two. In addition, because much of antarctic science is related to improving human understanding of global processes important to maintenance of Earth's environment, it would seem natural that environmental organizations become important allies of this work.

To move toward this inclusive and transparent relationship between those who are responsible for the governance of Antarctica and the public that supports activities there, the Committee believes that the regulatory, permitting, oversight and assessment processes established by legislation implementing the Protocol must provide for adequate opportunities for public participation. Such measures should include appropriate notice, opportunity for written comment and presentations at any public hearings, and decisionmaking on a record that takes public comment into account. In addition, the Protocol requires that certain information respecting, for example, environmental impact evaluations and inspection reports be made public. It is important that it be made public in a manner that is timely and encourages public evaluation and response.

In summary, the Committee believes that Antarctica has been served well by the interest of the public. The Protocol should not be viewed as a culmination or an end of that interest, but rather an opportunity to derive even greater benefits for Antarctica from the growing interest of a diverse public.

Recommendation 7: Legislation implementing the Protocol should contain opportunities for public involvement similar to those routinely established in domestic environmental and resource management legislation.

Liability

Individual responsibility and the attendant liability has become increasingly important in the design of environmental governance systems. The concept involves two issues: the kind of act for which a person will be held liable, and the nature of the sanction. On both scores, the potential exposure of the individual scientific investigator has been substantially increased over the past decade, in both the United States and Antarctica. Although this situation is difficult to quantify, it potentially could have a chilling effect on the creative conduct of science.

For example, scientists have traditionally understood that they would be held responsible if they purposely released a toxic substance into the environment with ensuing harmful effects. However, in some circumstances today, responsibility may be imposed even if the release of the substance was not planned or if the effect was wholly unanticipated.

The sanctions that society imposes for violations of social duties similarly have become much more complex and onerous, including the possibility of criminal sanctions and prison terms. These extensions in the scope of liability have raised serious concerns among potentially affected individuals. Liability is particularly difficult to integrate into the harsh and unique setting of science in Antarctica.

The Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties are developing an additional Annex on liability. In doing so, the Committee believes that the Parties should seek input from the scientific community in order to achieve their objectives in a way that would minimize the potential adverse impacts of liability on the conduct of science. Moreover, since U.S. legislation must ultimately be consistent with any international liability regime, the Committee suggests that the Congress may wish to defer addressing the issue of liability in implementing legislation until this international framework has been more clearly established and the negotiation of the Annex has been completed.

Conclusion

The implementing legislation and regulations will form the framework that will guide federal agencies and the scientists they support, as well as others, in achieving the goals of the Environmental Protocol. Tlie structure of the legislative and regulatory schemes, and the detailed ways in which they deal with the concerns discussed in this chapter, will have a major impact both on the nature of U.S. science in the Antarctic and on the manner in which that science is done. Further, the experience of the U.S. in developing legislative and regulatory approaches to the concerns expressed here could point the way for other ATCPs as they implement the Protocol.