Human Ecology and Behavior and Sexually Transmitted Bacterial Infections

KING K. HOLMES

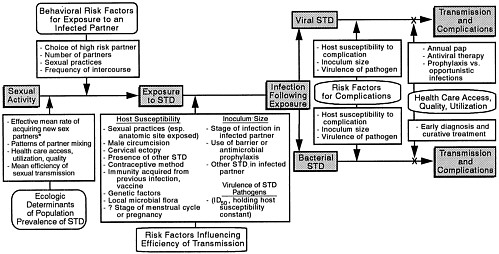

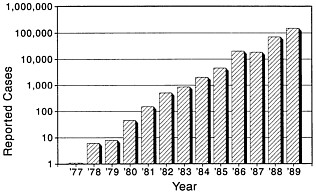

The four major bacterial sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, syphilis, and chancroid, all rank together with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among the top 25 diseases causing loss of healthy days of life in a representative high prevalence urban area of sub-Saharan Africa (1). The prevalence of bacterial STDs in many developing countries is extremely high (2). In China and Thailand, where national STD surveillance systems do exist, major epidemics of bacterial STDs have occurred in recent years (Figures. 1 and 2). In contrast, every Western industrialized country but one has eradicated chancroid as an endemic disease and dramatically reduced the incidence of gonorrhea and syphilis during the AIDS era. Many are bringing chlamydia under control. Only the United States allowed gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid to go out of control during the AIDS era, as summarized elsewhere in this issue by Wasserheit (3), and the United States has failed to implement a country-wide chlamydia control program.

Beyond the extensive morbidity caused directly by these four STDs, all represent risk factors for heterosexual transmission of HIV (4–8). STD may increase heterosexual transmission of HIV by producing genital inflammation in HIV-infected persons, thereby enhancing shedding of HIV in genital secretions (9–11), or by producing genital inflammation in

King K. Holmes is director, Center for AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Diseases, and professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle.

FIGURE 1 Trends in reported sexually transmitted diseases, People's Republic of China, 1977–1989.

individuals who are sexually exposed to HIV, thereby enhancing susceptibility to HIV acquisition. While community randomization trials of improved STD control for HIV prevention are planned or under way in Africa, the World Health Organization (12) and U.S. Agency for International Development (13) identify treatment of bacterial STDs as one of three available public health strategies (along with condom promotion and sexual behavior change) for preventing sexual transmission of HIV. Ironically, our own country, possessing resources and technical capabilities for control of bacterial STD, has not applied the same balanced

FIGURE 2 Trends in reported bacterial sexually transmitted diseases, Thailand, 1967–1992 (from the National Ministry of Health of Thailand). GC, gonorrhea; NGU, nongonococcol urethritis; LGV, lymphogranuloma venereum.

strategy within our borders. Neither promotion of condom use nor control of bacterial STDs has been aggressively pursued within the United States during the AIDS era.

Our failure to implement effective programs for preventing heterosexual HIV transmission may stem from the widespread but misguided belief that heterosexual AIDS is not a problem in the United States (14). Even as national surveillance showed that heterosexually acquired AIDS increased faster than AIDS in other risk groups every single year for the past 9 years, ultimately becoming the principal form of AIDS in women, we have allowed STD control to deteriorate in the United States. Better definition of the ecologic and behavioral determinants of the emergence of the bacterial STDs—all curable—provides the basic conceptual framework for rethinking prevention and control of STD/HIV in the 1990s.

The following discussion begins with current epidemiologic models of STD, then highlights available data on the three direct determinants of the rate of spread of STD, and finally, examines key ecologic and behavioral factors that operate through these direct determinants to explain the emergence of the four major bacterial STDs in developing countries and in subpopulations of the United States. The discussion compares causal factors in developing countries and in the United States and indicates how these factors operate at the population level and at the individual level.

EPIDEMIOLOGIC MODELS OF STD

Models of STD epidemiology draw on the concept of ''core groups" of individuals who can maintain the spread of an STD within a larger population. Various authors have defined "core groups" differently, for example, referring to those with repeated STDs, those living in high-prevalence areas, those with high-risk lifestyles (e.g., sex workers and their clients), or those with prevalence rates of STDs so high as to "preempt" the introduction of new infection into their group (15, 16).

Core groups (17–19) have also been defined in terms of transmission of STDs and three principle determinants of the rate of spread of STD have been delineated. The reproductive rate, R0, is the initial rate of secondary cases of STD arising from a new case. At R0 > 1, the STD spreads; at R0 < 1, it dies out. The three determinants of the rate of spread are the average risk of infection per exposure or efficiency of transmission (β); the average rate of sexual partner change within the population (c); and the average duration (D) of the infectious period for individuals with the STD. Thus R0 = β × c × D.

When the population prevalence of an STD is at equilibrium, then R0 = 1 and c = 1/βD. Based upon published or probable values for β and

D, Brunham and Plummer (20) have estimated values for the mean rate of partner change (c) required to sustain transmission of different bacterial STD. Without health care, D is large, and rates of partner change required for sustained transmission are highest for chancroid and syphilis, lowest for chlamydial infection, and intermediate for gonorrhea. With early diagnosis and treatment, D decreases, and the rate of partner change required to sustain transmission increases. In developing countries and poor urban areas with poor access to early treatment and prolonged infectiousness, lower rates of partner change sustain spread of bacterial STDs.

Subsequent work by Anderson (19) demonstrated that the greater the variance in rate of partner change within the population, the greater the calculated value of R0. Those with highest rates of partner change (the "core group") contribute disproportionately to STD transmission. In populations where a few persons have many partners, the high variance in partner change effects a high rate of STD transmission. Thus, for example, the crack cocaine epidemic, with frequent exchange of sex for drugs by a few individuals, has a potentially big influence on STD transmission.

Patterns of partner mixing also influence R0. At low mean rates of partner change, R0 is highest when those with many partners tend to have sex nonrandomly with others who themselves have many partners (21). Such "assortative" patterns of sexual mixing in poor urban areas may contribute to rapid spread of STDs.

In summary, STD prevalence and incidence in a particular sociogeographic setting is determined by factors that influence β, those that influence sexual behaviors (mean rate of partner change in the population, variance in rate of change, and patterns of partner mixing), and those that influence D (availability and use of good STD health care). The next section elaborates on the definition and current status of ecologic factors that most closely influence each of these three direct determinants of R0.

GLOBAL HEALTH CARE AND THE DURATION OF INFECTIOUSNESS OF BACTERIAL STDs

The quality, accessibility, and use of health care services determine the average duration of infectiousness of the bacterial STD. Early diagnosis and treatment, therefore, represent primary prevention of new infections and secondary prevention of complications.

Developing Countries

Bacterial STDs predominate among adult clinical consultations, disproportionately affecting those who cannot afford private care. Because

early diagnosis and treatment of STD have not been a high priority in the public health sector until now, many bypass the formal private and public health care systems for STD treatment. Men with urethritis often go directly to pharmacies, and often receive inappropriate, yet costly, therapy.

Women with bacterial STDs may not develop genital symptoms and would never undergo routine screening for these infections in developing countries; those who develop symptoms may not seek or find medical care; those who seek and find care seldom receive speculum or bimanual exams in the least developed countries; where such exams are done, microscopy and specific tests for gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, and Haemophilus ducreyi are rarely available. Although official policies require testing pregnant women for syphilis, many receive no prenatal care, and those who do often slip through without syphilis screening. Effective and relatively inexpensive STD drugs are now included on the international essential drug list but seldom reach primary care clinics that serve women. For those very select few infected women who might develop symptoms, seek care, be examined, have tests performed or receive a correct syndromic diagnosis, and receive effective therapy, treatment of the male partner is not attempted, and reinfection is likely.

Thus absence of the necessary clinical, laboratory, pharmacy, and public health infrastructure results in a very long average duration of infectiousness for bacterial STD. When combined with high-risk sexual behaviors and efficient transmission, very high equilibrium prevalence rates result.

The United States

There are several thousand public STD clinics in the United States, some free standing as categorical metropolitan STD clinics, often serving predominantly men; some integrated with family planning clinics serving predominantly women; some integrated with community or health department primary care clinics. Prior to the 1970s, STD clinics emphasized treatment and partner notification for syphilis and treatment of gonorrhea in men. Subsequently, STD clinics introduced several new services, such as gonorrhea culture testing of women, partner notification for gonorrhea, and vaginal speculum and bimanual pelvic examination. Uniform guidelines were developed by the Centers for Disease Control for treating conditions poorly managed earlier, such as nongonococcal urethritis, mucopurulent cervicitis, bacterial vaginosis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. Most recently, STD clinics have also expanded services for viral STD, including counseling and testing for HIV, and some provide cervical Pap smears.

Principal failings of our public STD clinics during the AIDS era include the inability to provide (i) sufficient access for all persons seeking health care (22), a problem worsened acutely by the added burden of HIV testing and counseling; (ii) hepatitis B vaccination of high-risk groups to reduce spread of the first vaccine-preventable STD; and (iii) nationwide diagnostic testing for Chlamydia trachomatis infection or partner notification for chlamydial infection or related syndromes.

Prior to 1992, only 1 of 10 regions in the United States, region X, received federal funds for a region-wide chlamydia screening program (23). About 150 family planning clinics in the Pacific Northwest began selective chlamydia screening in 1988. Chlamydia prevalence has since declined by >50% in women throughout the region. A few other areas, such as Wisconsin, where chlamydia control programs were also begun, replicated this experience. Screening is particularly effective in reducing transmission of chlamydial infection, because of the often silent nature and long duration of infectiousness.

In summary, inadequate health services for STD treatment provide an obvious explanation for the high rates of bacterial STD found in developing countries and in the inner cities and rural south of the United States. However, disproportionately high rates of viral STD that are little influenced by medical treatment indicate the importance of other ecologic and behavioral determinants in these same settings.

TRENDS AND PATTERNS OF SEXUAL BEHAVIORS

Developing Countries

Demographic data and ethnographic research suggest progressive liberalization of sexual behavior during the 19th and 20th centuries (24, 25), as a result of colonial and economic development, urbanization, population growth, and other factors discussed below. These changes probably best explain the subsequent epidemic spread of HIV and other STDs. Because of the HIV epidemic, qualitative behavioral research and formal sexual behavioral surveys have been undertaken recently in many countries. None approach the size of the sexual behavior surveys recently completed in the United Kingdom (26), France (27), or the United States (see below), but generalizations are possible. Invariably the rate of change of sex partners for men exceeds that for women. In six African countries surveyed in 1988–1990, the percentage of respondents who had engaged in casual or commercial sex in the last 12 months ranged from 8 to 44% for men, and 2–17% for women, with the percent of men engaging in such behavior 2–4 times higher than the percent of women in five of the countries (28). In Asia and Latin America, scattered

general population surveys indicate even higher differences in proportions of men and women engaging in casual or commercial sex. These gender differences in sexual behaviors in Asia and Latin America also exceed gender differences in the industrialized countries (26, 27).

The United States

Despite recent interference from Congress, several methodologically sound surveys of sexual behavior have been conducted in the United States. Zelnik and Kantner (29) studied adolescent sexual behavior in national probability samples in 1971, 1976, and 1979, documenting steadily increasing rates of premarital intercourse by teenaged females throughout the 1970s. The National Survey of Adolescent Males (30, 31) found that from 1988 to 1991, 17.5- to 19.0-year-old males experienced a significantly younger mean age of first intercourse and a significant increase, from 2.0 to 2.6, in the mean number of sexual partners over the past 12 months, with no increase in frequency of condom use. The 1973, 1976, 1982, and 1989 cycles of the National Survey on Family Growth (32) showed a continuing increase in the proportion of female teenagers 15–19 years old who were sexually experienced, from 28.6% in 1970 to 51.5% in 1988, including an increase among white teenagers from 44.1% to 51.5% during the AIDS era from 1985 to 1988. Similarly, the General Social Survey collected limited data annually from 1988 to 1990 on sexual behaviors of U.S. adults (33), providing perhaps the best comparison yet available of recent sexual behaviors of males and females, with data stratified by age, race, and marital status. Results help explain age and race disparities in rates of bacterial STD in the United States and suggest that >22.5 million U.S. adults had 2 or more sex partners during the preceding year, with an estimated 4.8 million having had 5 or more partners. The 1990 National AIDS Behavioral Surveys (34) assess HIV-related sexual risk behaviors. Most recently, from the landmark 1990 National Survey of Men (NSM-I), a series of five articles by Tanfer and coworkers (70–74), concerning sexual behaviors of men 20–39 years old, appeared in Family Planning Perspectives, March/April 1993. Age and race/ethnicity differences in numbers of sexual partners paralleled age and race/ethnicity disparities in bacterial STD rates in the United States and the General Social Survey results (33). We await results of the national survey of female sexual behavior from the same group.

These trends in heterosexual behavior over the last decade contrast with the well-documented dramatic decline in unsafe sexual behavior among homosexual/bisexual men, which strikingly cut rates of early

syphilis and rectal gonorrhea. Prior to 1982, syphilis in the United States predominantly involved homosexual or bisexual men (35). Subsequently, the incidence of syphilis and gonorrhea in gay men plummeted, although several cities now see growing numbers of young gay men with rectal gonorrhea.

Overall, sexual attitudes and behaviors became steadily more liberal in the United States throughout the 20th century. With oral contraception in the early 1960s came partial elimination of the double standard of sexual behavior of men and women. The sexual revolution extended to homosexual and bisexual men at the same time. During the 1970s and 1980s, an increasing percentage of young women had premarital intercourse, and recent birth cohorts have had more partners than earlier cohorts. During the AIDS era, gay men decreased risky sexual behaviors, but some young gay men now resume such behaviors. Surveys through 1990–1991 do not suggest dramatic reduction in multipartner, casual, or risky sex among heterosexuals, though more recent data are urgently needed. Cocaine-associated risky sexual behavior has emerged since 1985 as a major factor in the spread of bacterial STD.

DETERMINANTS OF EFFICIENCY OF TRANSMISSION OF STD

Three factors determine efficiency of STD transmission: the size of the microbial inoculum, the susceptibility of the host, and the infectious virulence of the pathogen (e.g., the ID50 for a given host). The stage of infection at exposure influences inoculum size, with highest inocula during early infection, with lesions or exudate. Continued sexual activity despite symptoms of STD can reflect lack of knowledge about STD, lack of access to care, dependence on income from commercial sex, or use of toxic drugs. The inoculum is reduced by use of condoms or microbicidal agents (e.g., spermicides) and, conceivably, by vaginal douching. Cultural differences in condom and spermicide use undoubtedly influence STD transmission. Finally, just as other STDs influence genital HIV shedding, genital infection or inflammation caused by one STD pathogen (e.g., gonorrhea) might also influence genital shedding of another bacterial STD pathogen (e.g., chlamydia) (36).

Host susceptibility to chancroid, and perhaps to syphilis and gonorrhea, is reduced by male circumcision (37). Traditional male circumcision practices probably protect some populations against these STDs. Male circumcision is less common in U.S. blacks (37) and Hispanics than in whites, creating an increased risk for these infections in blacks and Hispanics.

Cervical ectopy, which decreases with advancing age and increases with oral contraceptive use, increases susceptibility to chlamydial infection,

and perhaps to gonorrhea. Very young sexually active women and oral contraceptive users with ectopy are particularly susceptible to chlamydial infection. Early average onset of intercourse among females or high rates of oral contraceptive use probably foster rapid transmission of chlamydial infection.

Variations in infectious virulence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae may influence efficiency of transmission of gonorrhea. Certain strains of N. gonorrhoeae are resistant to fecal acids, and are more prevalent among homosexual men, probably because of more efficient transmission by rectal intercourse (38). Other strains that tend to cause disseminated gonococcal infection, with bacteremia and tenosynovitis, are highly susceptible to fecal acids, and uncommon in gay men, perhaps explaining why disseminated gonococcal infection has been relatively uncommon among gay men.

ECOLOGIC FACTORS INFLUENCING THE EMERGENCE OF BACTERIAL STD

Having considered the three direct determinants of the rate of spread of bacterial STD, we next consider underlying ecologic factors that have influenced the emergence of bacterial STD.

Historical Stages of Economic Development

As the economy evolved from hunting to agriculture to industry, patterns of sexual behavior, reproduction, moral codes, and religion presumably adapted. With the transition from hunting to agriculture, children became economic assets at an early age, the family became the unit of production, and land became a valuable commodity to be passed on from father to son. Early marriage, monogamy, and multiple births were reinforced by religion and moral codes (39). In sociobiological terms "greater predictability of food in space and time promotes the evolution of territoriality. When the resources are dense and easily defensible, and when food is the limiting resource, the optimum strategy is the double defense—by means of the monogamous pair bond" (40).

With the industrial revolution in Europe and North America, the family unit fragmented, as parents and children left the home and village to find work in cities, children no longer were economic assets, marriage was delayed, secular institutions began to replace religious and moral codes, and premarital and extramarital sex became more common. This scenario is replayed conspicuously today in the emerging countries throughout Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

Geography, Crowding, and Hygiene

Climate, crowding, and hygiene profoundly influence the epidemiology of the nonvenereal treponematoses of childhood (yaws, pinta, and endemic syphilis). Crowding, primitive conditions, and poor hygiene have characterized settings permitting spread of endemic syphilis, typically within family units, and yaws persists in some developing tropical countries. At one time, endemic syphilis was a problem even in Northern Europe and North America, disappearing as living conditions improved. The WHO/UNICEF-coordinated global program for eradication of the endemic treponematosis in the 1950s and 1960s greatly reduced yaws prevalence throughout the developing world. Endemic syphilis was eradicated in Bosnia, and pinta disappeared in Latin America. The next generations were rendered fully susceptible to adult syphilis, as immunity from the childhood treponematoses no longer occurred and sexual behaviors became more liberal. Many tremonematologists believe all clinical and epidemiological differences between venereal syphilis of adults and endemic syphilis in children, and perhaps even between syphilis and yaws, reflect ecologic factors and sexual behaviors, rather than essential differences in pathogenicity of Treponema pertenue (the cause of yaws) and the variants of Treponema pallidum associated with endemic syphilis of children or venereal syphilis of adults.

Similarly, poor hygiene, flies, and crowding characterize the epidemiologic niche for ocular trachoma strains of C. trachomatis (serovars A, B, Ba, and C) while sexually transmitted LGV strains of C. trachomatis now require tropical developing country settings, whereas genital serovars D-K of C. trachomatis cause urethral and cervical infections throughout the world.

Modern studies have not sufficiently addressed the effectiveness of hygiene or use of antiseptics in preventing transmission or acquisition of chancroid or syphilis in high-risk populations.

"Socio-Geographic Space" and Bacterial STDs

The influence of geography, crowding, and hygiene on transmission of the endemic treponematoses, chlamydia, and chancroid somewhat presages current concepts of the social and spatial concentrations of STD, and the spread of these infections along social networks and spatial contiguity or transportation links (41-44). Rothenberg (41) and others (45) documented geographic clustering of high gonorrhea incidence in a few urban census tracts. An impact on AIDS and STD of shortsighted policies for public services—not only public health services

but also fire control, housing, and others—has been inferred by Wallace (43), who decried how planned reduction in capacity to contain urban fires led to spreading urban decay, and the physical and social "ghettoization" of the Bronx. While sexual behaviors and health care most directly determine the rate of introduction and removal of bacterial STDs in the population, the patterns of introduction, spread, and removal within and between communities are determined by social networks and spatial factors, influenced by urban/community planning and services.

War, Travel, and Migration

Quinn (46) discusses these factors separately in this volume as determinants of the spread of HIV infection. They equally influence spread of bacterial STD. The possible contribution of epidemic urban decay and resulting migration described by Wallace (43) to the reemergence of gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid in the United States provides one example. Global examples include the epidemic increases in gonorrhea and syphilis in the industrialized countries during and after World Wars I and II and in the United States during and after the Vietnam War, and the rapid global spread of two types of β-lactamase-encoding plasmids in gonococci from separate regional foci in Asia and Africa in the 1970s. The resurgence of reported STDs in China (Figure 1) accompanied reopening of the country to foreign visitors, movement of the male work force within the country to industrial centers, and reemergence of a commercial sex industry in response. Similarly, the growth of the commercial sex industry in Thailand accompanied increased military, work-related, and tourist travel and urbanization, all of which fueled epidemic STD (Figure 2). Indeed the classic tendency of one country to attribute STD epidemics to another country (e.g., syphilis, as both "The French Disease" in Italy and "The Italian Disease" in France at the end of the 15th century) generally reflects changing behaviors in both countries during periods of war, migration, or increased travel.

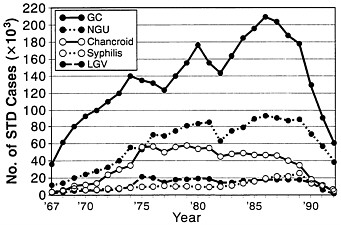

The Demographic and Epidemiologic Transitions

Figure 3 contrasts the age distribution of the population of the world's developing regions with that of the industrialized countries in 1980 and shows projected growth to the year 2000. Young people predominate now in developing regions and will become even more predominant. Furthermore, the percentage of the world's population living in urban areas will grow from 37% in 1985 to 45% by the year 2000 and to 61% by

FIGURE 3 World population by age and sex for 1980 and projected for the year 2000 for developed and developing regions (United Nations).

2025 (47); in developing countries, this urban migration selectively involves young adults, typically young men. This will further markedly increase the relative numbers of young adults within cities, creating even a larger predominance of young men in cities (48).

Declining birth rates plus increasing life expectancy is producing a demographic transition to an older population in Western industrialized countries. This leads in turn to an epidemiologic transition, in which aging of the population, improved economic and health infrastructures, and declining rates of death from childhood communicable diseases result in older average age at death and growing morbidity from noncommunicable diseases of adults.

However, in developing countries, especially in Africa and South Asia, birth rates remain high, and child survival improves due to successes of the extended program on immunization, use of oral rehydration solution treatment for diarrhea, and improved care of acute respiratory infection. Rapidly growing numbers of children who survive cause a sustained and disproportionate surge in the size of the adolescent and young adult age groups, both in absolute numbers and relative

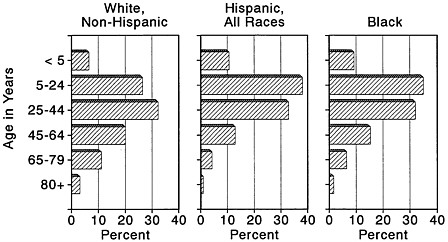

FIGURE 4 Distribution of the population of the United States by age, race, and Hispanic origin in 1990 [Bureau of the Census (1990); Census of Population; General Population Characteristics (1990); Census of Population CP-1-1;17-24].

to the size of the older population. The success of child survival programs and comparative failure of family planning programs in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have led to an unanticipated stage in the epidemiologic transition (49), the epidemic of communicable diseases of adolescents and young adults (i.e., STDs/AIDS).

Figure 4 shows the age distribution of the population of the United States in 1990 for blacks, Hispanics of any race, and non-Hispanic whites. The proportion of blacks and Hispanics from 5 to 24 years old substantially exceeds that of whites, so that the age pyramid for these U.S. minorities lies intermediate between that of the developing regions and that of industrialized countries.

Ages of Sexual Maturation and of Marriage

The average age of sexual maturation declined steadily during the 19th and 20th century in industrialized countries. In the Nordic countries, average age at menarche was about 16 years in the mid to late 19th century, falling steadily to 13 by the mid 20th century (50). Menarche generally occurs later in developing countries, but earlier in urban than in rural areas. This progressively earlier sexual maturation and the progressively delayed mean age of marriage greatly extends the duration of time that premarital intercourse can occur, making social, cultural, and religious proscriptions less effective than in the past.

Social and Economic Development Policies in Developing Countries

The low status of women and economic development policies that move the male work force away from families and communities into urban industrial centers contribute to the epidemics of STD/HIV in many developing countries (24, 48, 51). The relatively poor educational opportunities for women leave them ill-prepared for economic survival outside of marriage, especially after child-bearing. This problem, where coupled with the emergence of urban or periurban male slums, fosters casual and commercial sex and a new generation of urban or periurban teenagers with one available parent (who may be a sex worker) and without a stabilizing extended family or community.

In summary, interrelated factors, including separation of families with male urban migration, low status of women, increasing urban, periurban, and interurban prostitution, a demographic transition characterized by growing and destabilizing excesses of teenagers and young adults no longer under the regulatory influence of a nuclear or extended family or community, and war, migration, and travel, have fostered changes in sexual behavior and epidemics of STD in developing countries during the 20th century. Many similarities are evident in the United States.

A ''Synergism of Plagues": STD/HIV, Teen Pregnancy, Violence, and Cocaine Use

In the United States, bacterial STDs, such as gonorrhea, syphilis, and chancroid, concentrate in black and Hispanic populations, particularly among teenagers. The enormous disparity between blacks and whites in annual rates of gonorrhea and syphilis has actually grown since 1985. Because this disparity largely depends upon basic structural disparities in socioeconomic attainment and in access to health care, it is not surprising that the determinants of the STD epidemic in the United States and in developing countries are similar. Race and ethnicity should be viewed not as risk factors per se but as risk markers for a more complex set of underlying socioeconomic, cultural, political, behavioral, and environmental risk factors.

Specifically, the nature of the demographic transition in black and Hispanic U.S. populations, a steeply rising proportion of children being born to unmarried mothers, fragmentation of the family and community, counter-productive social welfare policies, and a unique form of commercial sex related to use of crack cocaine have been the prime determinants of changing sexual behaviors; and the failure of the public

health infrastructure to cope with rising rates of STD has worsened the problem in the United States.

In 1991, 1.2 million U.S. children born to unmarried mothers represented 28% of all births. This included 68% of all births to black women, up from 26% in the 1960s; 41% of births to Hispanic mothers; and 17% of births to white women, ranging up to 44% of white women in poverty (52). The overall birth rates and pregnancy rates for U.S. teenagers in 1990 exceeded those of most developing countries (52). In 1990, 521,000 births to U.S. women 15-19 years of age represented a 20% increase from 1986 to 1990 in rate of births to teenaged women. Birthrates per 1000 women 15-19 years of age in 1990 were 42.5 for non-Hispanic white, 100.3 for black, and 116.2 for Hispanic women (53).

Trends in statistics for child neglect and abuse and in placement of children in foster home care provide further evidence of family fragmentation. Nationally, 2.2 million children were referred to child protective services in 1986, and an estimated 270,000 children nationally were in foster care (54), a 223% increase since 1976. The urban situation is worse. Reports of child abuse or neglect totaled 52,504 in New York City alone in 1992, and the number of children in foster homes in New York City increased from ≈18,000 in 1985 to nearly 50,000 in 1992 (data from Management and Analysis, Child Welfare Administration, Human Resources Administration, City of New York). Children commonly transfer from one family to another in the foster care system, some having been placed in 10 or more homes, precluding consistency in family values or approaches to child rearing.

In a disturbing recent article entitled "The Coming of the White Underclass," Murray (55) argues that this extraordinary increase in births to young poor single women and the resulting family fragmentation are due to social welfare policies that encourage single parenthood, policies that are the root cause of the growing problem with antisocial behavior in young people in the United States.

Not surprisingly, multiple interrelated epidemics of behavioral and emotional problems now converge in U.S. adolescents, with the epidemics of STD/HIV accompanied by concurrent epidemics of gang-related crime and violence, drug use involving teenagers, sustained high rates of teen pregnancies, and increasing rates of live births to teenage girls. In an analysis of retrospective data from successive birth cohorts of adults studied in the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiological Catchment Area Program, Robins (56) found that the proportion meeting criteria for adolescent antisocial conduct disorder had increased from 0.5% of females and 6% of males in the oldest (65+) cohort, to 13% of females and 36% of males in the youngest (18-29) cohort. Nationally, with ≈1,000,000 admissions per year of adolescents

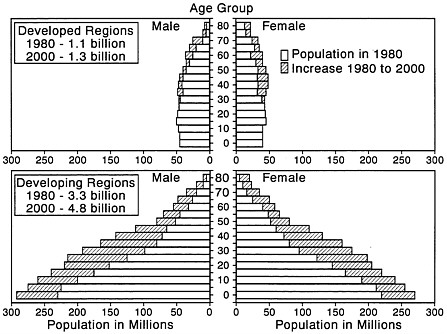

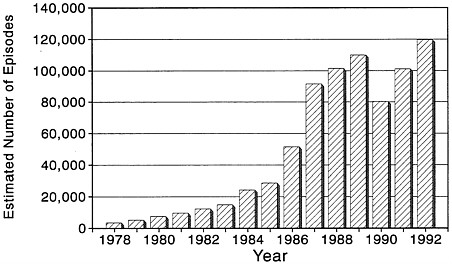

FIGURE 5 Estimated number of emergency room encounters for cocaine use in the United States from 1978 to 1992 [from the U.S. Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) surveillance system] (59).

into juvenile detention facilities, the average number of adolescents in detention is ≈ 125,000, at an average cost of about $40,000 per detainee per year.

The crack epidemic contributes to the related epidemics of violence, child abuse and neglect, and the resulting placement of children in foster care. The epidemic of freebase (later crack) cocaine use appeared as early as 1982 in the Bahamas (57), where it was temporally and epidemiologically associated with major epidemics of HIV and genital ulcer disease, including chancroid, syphilis, and lymphogranuloma venereum, caused by the L2 strain of C. trachomatis (unpublished data). Crack use spread throughout the United States during the mid 1980s. Although the estimated number of current cocaine users dropped from a peak of 5.8 million in 1985 to 1.3 million in 1992 (58), the number of weekly users has not fallen since 1985. The estimated number of emergency room encounters for cocaine use increased rapidly from 1983 to 1989 (Figure 5). After an encouraging decline in 1990, the numbers shot up again in 1991 and 1992 (59). These encounters presumably reflect those cocaine users getting into most difficulties with the drug. Further, the percentage of cocaine users seen in emergency rooms who acknowledged use by smoking increased from 41% in 1990 to 53% in 1992, and as the "purity" of street cocaine rose from 58% in 1990 to 74% in 1992, the number of emergency room encounters for cocaine overdose rose by 47%.

The epidemics of teenage antisocial behaviors and crack use clearly promote the epidemic spread of bacterial STD. In juvenile detention populations, the combined prevalence of gonorrhea and chlamydial infection typically averages ≈20% in girls. Gonorrhea is now linked to membership in street gangs (60). Crack use is directly related to syphilis, gonorrhea, and chancroid, as well as HIV infection (61). Crack use leads to several STD risk behaviors, including exchange of sex for drugs or money (62).

New Technology and Product Development

Epidemic increases in gonorrhea and other STD in industrialized countries closely followed the introduction of oral contraceptives, which liberalized the sexual behavior of women, increased the efficiency of sexual transmission of chlamydial infection and perhaps of gonorrhea, and decreased condom use for contraception. On the other hand, family planning programs are now lowering fertility rates and slowing population growth, even where economic progress is slow (63), and this ultimately should slow STD spread.

Development of fluoroquinolones and new oral cepholosporins has made oral therapy for gonorrhea and chancroid more feasible, even through pharmacies, possibly contributing to the recent decline in cases reported from STD clinics in Thailand (Figure 2).

ECOLOGIC AND BEHAVIORAL DETERMINANTS OF COMPLICATIONS AND SEQUELLAE OF BACTERIAL STDS

The many complications of bacterial STD result from extension from lower to upper genital tract; bacteremia; pregnancy or puerperal infectious morbidity; congenital or perinatal transmission; or immunopathologic host responses. Good health care access, quality, and utilization provide secondary prevention of these complications. Other behaviors also influence complications. For example, vaginal douching is associated with increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (64, 65), is more common among black women (65, 66), and may contribute to high rates of pelvic inflammatory disease and its sequellae in black women. Conversely, oral contraception use seems to decrease the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease among women with cervical chlamydial infection (67).

HIV infection may influence the risk and severity of pelvic inflammatory disease among women with gonorrhea and may increase the risk of neurologic complications of syphilis (68). Finally, variation in the bacterial STD pathogens themselves influences disease manifestations. For

example, strains of N. gonorrhoeae that require arginine, hypoxanthine, and uracil for growth accounted for a high proportion of cases of gonorrhea in the United States and Europe during the 1960s and 1970s and caused most cases of gonococcal bacteremia. For unknown reasons, these strains have nearly disappeared from the United States, and disseminated gonococcal infection has become a rare disease.

POPULATIONAL VS. INDIVIDUAL DETERMINANTS OF STD RISK

In summary, at the population level, the prevalence and pattern of distribution of the direct determinants of R0 influence the prevalence, incidence, trends, distribution, and complications of the four major bacterial STDs. These direct determinants are in turn strongly influenced by underlying ecologic factors, including structural socioeconomic factors, and development/welfare policies that are the true cause of the modern global emergence of STD and AIDS. These underlying factors must be addressed as public health programs are strengthened.

As summarized in Figure 6, for any individual, the risk of exposure to an STD depends upon the ecological (i.e., sociogeographic) setting in which partners are chosen as well as upon the individual's own sexual behaviors (such as choice of partner within that setting and frequency of partner change and sexual practices). A woman who lives and works in the Bronx (where bacterial STDs are out of control) and has only one sexual partner may have much higher risk of exposure to a bacterial STD than a woman who has 10 sex partners in Sweden (where bacterial STDs are under excellent control) (69). The risk factors influencing risk of acquiring an STD by the exposed individual, when summed across individuals, define the mean efficacy of transmission for the population. At the individual level, health care behaviors influence risk of complications, as well as risk of further transmission. Clear understanding and clear thinking about the populational and individual determinants of STD/HIV transmission and complications are required for developing, prioritizing, and implementing public health strategies for disease prevention.

Fortunately, many of these strategies are now well understood and formulated by international agencies (12). Implementation of effective programs for sexual behavior change, condom promotion, and STD treatment still represents a formidable technical and economic challenge for developing countries. However, in the United States, the technical skills are available, and only a small fraction of funds currently spent on AIDS and other complications of STD would be required for more effective control of bacterial STD. There is no longer any conceivable rationalization for not proceeding.

SUMMARY

The three direct determinants of the rate of spread of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are sexual behaviors, the mean duration of infectiousness, and the mean efficiency of sexual transmission of each STD. Underlying ecological and behavioral factors that operate through one or more of these direct determinants lie on a continuum, ranging from those most proximate back to those more remote (in time or mechanism) from the direct determinants. Most remote and least modifiable are the historical stages of economic development that even today conspicuously influence patterns of sexual behavior. Next are the distribution and changing patterns of climate, hygiene, and population density; the global population explosion and stages of the demographic transition; and ongoing changes in human physiology (e.g., menarche at younger age) and culture (e.g., later marriage). More proximate on the continuum are war, migration, and travel; and current policies for economic development and social welfare. Most recent or modifiable are technologic and commercial product development (e.g., oral contraceptives); circumcision, condom, spermicide, and contraception practices; patterns of illicit drug use that influence sexual behaviors; and the accessibility, quality, and use of STD health care. These underlying factors help explain why the curable bacterial STDs are epidemic in developing countries and why the United States is the only industrialized country that has failed to control bacterial STDs during the AIDS era.

REFERENCES

1. Over, M. & Piot, P. (1993) in Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries, eds. Jamison, D. T., Mosley, W. H., Measham, A. R. & Bobadilla, J. L. (Oxford Univ. Press, New York), pp. 455–527.

2. Brunham, R. C. & Embree, J. E. (1992) in Reproductive Tract Infection: Global Impact and Priorities for Women's Health, eds. Germaine, A., Holmes, K. K., Piot, P. & Wasserheit, J. (Plenum, New York), pp. 35–58.

3. Wasserheit, J. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 2401–2406.

4. Cameron, D. W., Simonsen, J. N. & D'Costa, L. J. (1989) Lancet ii, 403–407.

5. Plummer, F. A., Simonsen, J. N., Cameron, D. W., Ndinya-Achola, J. O., Kreiss, J. K., Gleinya, M. N., Waiyaki, P., Cheang, J., Piot, P., Ronald, A. R. & Ngugi, E. N. (1991) J. Infect. Dis. 163, 233–239.

6. Laga, M., Manoka, A., Kivuvu, M., Malele, B., Tuliza, M., Nzila, N., Goeman, J., Behets, F., Batter, V., Alary, M., Heyward, W. L., Ryder, R. W. & Piot, P. (1993) AIDS 7, 95–102.

7. Wasserheit, J. N. (1991) Sex. Transm. Dis. 19, 61–77.

8. Stamm, W. E., Handsfield, H. H., Rompalo, A. M., Ashley, R. L., Roberts, P. L. & Corey, L. (1988) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 260, 1429–1433.

9. Kreiss, J. K., Coombs, R., Plummer, F. A., Holmes, K. K., Nikora, B.,

Cameron, W., Ngugi, E., Ndinya-Achola, J. O. & Corey, L. (1989) J. Infect. Dis. 160, 380–384.

10. Plummer, F. A., Wainsberg, M. A. & Plourde, P. (1990) J. Infect. Dis. 161, 810–811.

11. Clemetson, D. A., Moss, G. B., Willerford, D. M., Hensel, M., Emonyi, W., Holmes, K. K., Plummer, F., Ndinya-Achola, J. O., Roberts, P. L., Hillier, S. & Kreiss, J. (1993) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 269, 2860–2864.

12. Merson, M. H. (1993) Science 260, 1266–1268.

13. Cohen, M. S., Dalabetta, G., Laga, M. & Holmes, K. K., (1994) Ann. Int. Med., 120, 340–341.

14. Fumento, M. (1993) The Myth of Heterosexual AIDS (Regnery Gateway, Washington, DC).

15. Yorke, J. A., Hethcoate, H. W. & Nold, A. (1978) Sex. Transm. Dis. 5, 51–56.

16. Hethcoate, H. W. & Yorke, J. (1984) Lecture Notes in Biomathematics (Springer, New York), No. 56.

17. Anderson, R. M. & May, R. M. (1988) Nature (London) 333, 514–519.

18. Anderson, R. M. & May, R. M. (1991) Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, U.K.).

19. Anderson, R. M. (1991) in Research Issues in Human Behavior and Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the AIDS Era, eds. Wasserheit, J. N., Aral, S. O. & Holmes, K. K. (Am. Soc. Microbiol., Washington, DC), pp. 38–60.

20. Brunham, R. C. & Plummer, F. A. (1990) Med. Clin. North Am. 74, 1339–1352.

21. Garnett, G. F. & Anderson, R. M. (1993) Sex. Transm. Dis. 20, 181–191.

22. Aral, S. & Holmes, K. K. (1991) Sci. Am. 264, 62–68.

23. Britton, T. F., DeLisle, S. & Fine, D. (1992) Am. J. Gynecol. Health 6, 24–31.

24. Caldwell, J. & Caldwell, P. (1990) Sci. Am. 262, 118–125.

25. Caldwell, J. C. & Caldwell, P. (1983) World Health Stat. Q. 36, 2–34.

26. Johnson, A. M., Wadsworth, J., Wellings, K., Bradshaw, S. & Field, J. (1992) Nature (London) 360, 410–412.

27. Analyse des Comportements Sexual en France (ACSF) Investigators (1992) Nature (London) 360, 407–409.

28. Caraël, M., Cleland, J., Adeokun, L. & Collaborating Investigators (1991) AIDS 5, 565–574.

29. Zelnik, M. & Kantner, J. F. (1980) Fam. Plan. Perspect. 12, 230–231, 235–237.

30. Sonenstein, F. L., Pleck, J. H. & Ku, L. C. (1989) Fam. Plan. Perspect. 21, 151–158.

31. Ku, L., Sonenstein, F. L. & Pleck, J. H. (1993) Am. J. Publ. Health 83, 1609–1615.

32. Centers for Disease Control (1991) Morbid. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 39, 929–932.

33. Anderson, J. E. & Dahlberg, L. L. (1992) Sex. Transm. Dis. 19, 320–325.

34. Catania, J. A., Coates, T. J., Stall, R., Turner, H., Peterson, J., Hearst, N., Dolcini, M. M., Hudes, E., Gagnon, J., Wiley, J. & Groves, R. (1992) Science 258, 1101–1106.

35. Blount, J. H. & Holmes, K. K. (1976) in The Biology of the Parasitic Spirochetes, ed. Johnson, R. C. (Academic, New York), pp. 157–176.

36. Batteiger, B. E., Fraiz, J., Newhall, W. J., Katz, B. P. & Jones, R. B. (1989) J. Infect. Dis. 159, 661–669.

37. Cook, L. S., Koutsky, L. A. & Holmes, K. K. (1993) Genitourin. Med. 69, 262–264.

38. Morse, S. A., Lysko, P. G., McFarland, L., Knapp, J. S., Sandström, E. G., Critchlow, C. W. & Holmes, K. K. (1982) Infect. Immun. 37, 432–438.

39. Durant, W. & Durant, A. (1968) The Lessons of History (Simon & Schuster, New York).

40. Wilson, E. O. (1980) Sociobiology: The Abridged Edition (Belknap Press, Cambridge, MA), p. 256.

41. Rothenberg, R. B. (1983) Am. J. Epidemiol. 117, 688–694.

42. Potterat, J. J., Rothenberg, R. B., Woodhouse, D. E., Muth, J. B., Pratts, C. I. & Fogle, J. S. (1985) Sex. Transm. Dis. 12, 25–32.

43. Wallace, R. (1990) Soc. Sci. Med. 31, 801–813.

44. Wallace, R. (1991) Soc. Sci. Med. 33, 1155–1162.

45. Rice, R. J., Roberts, P. L., Handsfield, H. H. & Holmes, K. K. (1991) Am. J. Public Health 81, 1252–1258.

46. Quinn, T. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 2407–2414.

47. Rossi-Espagnet, A., Goldstein, G. B. & Tabibzadeh, I. (1991) World Health Stat. Q. 44, 185–244.

48. Decosas, J. & Pedneault, V. (1992) Health Policy Planning 7, 227–233.

49. Rogers, R. G. & Hackenberg, R. (1987) Soc. Biol. 34, 234–243.

50. Bell, T. A. & Hein, K. (1984) in Sexually Transmitted Diseases , ed. Holmes, K. K. (McGraw-Hill, New York), pp. 73–84.

51. Larson, A. (1989) Rev. Infect. Dis. 11, 716–731.

52. Centers for Disease Control (1993) Morbid. Mortal. Wkly. Rept. 42, 733–737.

53. Centers for Disease Control (1993) Morbid. Mortal. Wkly. Rept. 42, 398–403.

54. Trupin, E. W., Tarico, V. S., Low, B. P., Jemelka, R. & McClellan, J. (1993) Child Abuse Neglect 17, 345–355.

55. Murray, C. (1992) The Wall Street Journal, Oct. 29.

56. Robins, L. N. (1988) in Risk in Intellectual and Psychosocial Development, eds. Farran, D. C. & McKinney, J. D. (Academic, New York), pp. 261–269.

57. Jekel, J. F., Allen, D. F. & Podlewski, H. (1986) Lancet i, 459–462.

58. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (1993) Preliminary National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Advance Report No. 3 (Dept. of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC).

59. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (1993) Estimate from the Drug Abuse Warning Network 1992 (Dept. of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC).

60. Centers for Disease Control (1993) Morbid. Mortal. Wkly. Rept. 42, 25–28.

61. Marx, R., Aral, S. O., Rolfs, R. T., Sterk, C. E. & Kahn, J. G. (1991) Sex. Transm. Dis. 18, 92–101.

62. Greenberg, J., Schnell, D. & Conlon, R. (1992) Sex. Transm. Dis. 19, 346–350.

63. Speidell, J. J. (1993) Physician Soc. Responsibility Q. 3, 155–165.

64. Wølner-Hanssen, P., Eschenbach, D. A., Paavonen, J., Stevens, C. E., Critchlow, C., DeRouen, T. & Holmes, K. K. (1990) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 263, 1936–1941.

65. Chow, W.-H., Daling, J. R., Weiss, N. S., Moore, D. E. & Soderstrom, R. (1985) Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 153, 727–729.

66. Aral, S. O., Mosher, W. D. & Cates, W., Jr. (1992) Am. J. Public Health 82, 210–214.

67. Wølner-Hanssen, P., Eschenbach, D. R., Paavonen, J., Kiviat, N., Stevens, C., Critchlow, C., DeRouen, T. & Holmes, K. K. (1990) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 263, 54–59.

68. Musher, D. M. (1991) J. Infect. Dis. 163, 1201–1206.

69. Cronberg, S. (1993) Genioturin. Med. 69, 184–186.

70. Billy, J. O. G., Tanfer, K., Grady, W. R. & Klepinger, D. H. (1993) Fam. Plan. Perspect. 25, 52–60.

71. Tanfer, K., Grady, W. R., Klepinger, D. H. & Billy, J. O. G. (1993) Fam. Plan. Perspect. 25, 61–66.

72. Grady, W. R., Klepinger, D. H., Billy, J. O. G. & Tanfer, K. (1993) Fam. Plan. Perspect. 25, 67–73.

73. Klepinger, D. H., Billy, J. O. G., Tanfer, K. & Grady, W. R. (1993) Fam. Plan. Perspect. 25, 74–82.

74. Tanfer, K. (1993) Fam. Plan. Perspect. 25, 83–86.