3

Consequences of Unintended Pregnancy

Does it matter whether a pregnancy is unintended at the time of conception—mistimed or unwanted altogether? There is a presumption that it does—that unintended pregnancy has a major impact on numerous social, economic, and cultural aspects of modern life. But it is important to define what these consequences might be. Accordingly, this chapter examines five sets of information that help to answer this important question. The first section addresses elective termination of pregnancy, because about half of all unintended pregnancies in the United States are resolved by abortion. As such, abortion can be seen as one of the primary consequences of unintended pregnancy. The second section considers the fact that unintended pregnancy is more common among unmarried women and women at either end of the reproductive age span (Chapter 2)—demographic attributes which themselves carry increased medical or social risks for children and/or their parents.

The final three sections address additional consequences of unintended pregnancy. The third section analyzes a complex set of studies in which the intendedness of pregnancy itself is related to a variety of outcomes for both the child (such as birthweight and cognitive development) and parents (such as educational achievement). These studies allow one to consider whether pregnancy intention itself affects various child and parental outcomes. The fourth consequence explored is that opportunities for preconception health assessment and care are often missed when pregnancy occurs unintentionally. Preconception care is still a developing field of clinical practice, but its potential impact is important. The fifth section of the chapter analyzes how some dimensions of the childbearing population in the United States would change if unwanted pregnancies were eliminated altogether and mistimed ones were redistributed

(typically, postponed). This statistical exercise helps provide an understanding of the consequences of current demographic patterns of unintended pregnancy and subsequent childbearing.

Abortion as a Consequence Of Unintended Pregnancy

As the Chapter 2 discussed, about half of all unintended pregnancies end in abortion. Accordingly, the occurrence of abortion can be seen as one of the primary consequences of unintended pregnancy. Voluntary interruption of pregnancy is an ancient and enduring intervention that occurs globally whether it is legal or not. The legalization of abortion in all of the United States, accomplished through the 1973 Supreme Court ruling Roe v. Wade, served in large part to replace illegal abortion (as well as abortion obtained outside of the United States) with legal abortion in this country. It is estimated that before the legalization of abortion, about 1 million abortions were being performed annually, few of them legally, and somewhere between 1,000 and 10,000 women died annually from complications following these often poorly performed procedures. Before the Supreme Court ruling, abortion was probably the most common criminal activity in this country, surpassed only by gambling and narcotics violations (Luker, 1984; Jaffe et al., 1981).

A 1975 report by the Institute of Medicine documented the benefits to public health by the legalization of abortion. The Supreme Court decision was followed not only by a decline in the number of pregnancy-related deaths in young women (Cates et al., 1978) but also by a decline in hospital emergency room admissions because of incomplete or septic abortions, conditions that are more common with illegally induced abortions (Institute of Medicine, 1975).

Given the long-standing reliance on abortion to resolve many unintended pregnancies, it is important to consider available information about the major medical and psychological risks that this procedure may pose (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Reproductive Epidemiology Unit, 1994; Frye et al., 1994; Lawson et al., 1994). From the voluminous data available for review, two important findings stand out that are often overlooked in the controversy over this procedure. First, whatever the risks associated with legal abortion in the United States, it remains a far less risky medical procedure for the woman than childbirth; over the 1979–1985 interval, for example, the mortality associated with childbirth was more than 10 times that of induced abortion (Council on Scientific Affairs, American Medical Association, 1992). Second, abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy carries fewer risks to health than abortion in the second trimester of pregnancy and beyond.

Medical Complications

As with any surgical procedure, abortion carries an inherent risk of medical complications, including death. Complications known to be directly related to the procedure include hemorrhage, uterine perforation, cervical injury, and infection, which is often due to incomplete abortion. Later complications that have been investigated include possible negative effects on subsequent pregnancy outcomes, particularly low birthweight, midtrimester spontaneous abortion, and premature delivery. The vast majority of abortions performed in this country are first-trimester vacuum aspiration procedures. Pregnancy outcomes among women who have had one vacuum aspiration abortion are no different than those among women who have not had an abortion. Results are mixed, however, as regards the influence on subsequent pregnancy outcomes of having had more than one abortion or having second-trimester abortions by vacuum extraction. At present, investigators are studying a possible relationship between abortion and an increased risk of developing premenopausal breast cancer (Daling et al., 1994).

Rates of Complications

To assess the frequency with which the well-documented complications of abortion occur, between 1970 and 1978 the Centers for Disease Control and the Population Council conducted the Joint Program for the Study of Abortion in three waves: 1970–1971, 1971–1974, and 1975–1978. These surveys showed that the risk of developing major complications 1 from legal abortion decreased greatly during the 1970s: from 1.0 percent in the first wave to 0.29 percent in the last (Buehler et al., 1985; Cates and Grimes, 1981; Grimes et al., 1977; Tietze and Lewit, 1972). Although the total complication rate2 increased from 9.0 to 14.8 percent over the three waves, this probably reflected an increased follow-up rate, a change in the distribution of firstand second-trimester abortions among the study populations, and an increase in reports of minor complications. Alternatively, the change may have been due to an actual increase in complications. More recent data show a total complication rate of induced abortion of less than 1 percent (Gold, 1990; Hakim-Elahi et al., 1990).

In all waves, the risk of all complications increased steadily with increasing gestational age, being lowest for women obtaining abortions at ≤ 8 weeks of gestation and increasing 2 to 10 times for procedures after 12 weeks of gestation. Complication rates were lowest among women whose abortions were performed using suction curettage and increased with more invasive procedures (those often used for more advanced pregnancies).

Trend data are also available on mortality. The annual number of legal-abortion-related deaths decreased from 24 deaths in 1972 to 6 in 1987, and the mortality rate decreased from 4.1 per 100,000 abortions in 1972 to 0.4 in 1987. As with overall complication rates, the risk of mortality is lower for abortions performed by suction or sharp curettage during the first trimester and for pregnancies of lower gestational age (Lawson et al., 1994). The risk of mortality is higher, however, for nonwhite women, women 35 years of age and older, and for women of higher parity.

The increased risk of both morbidity and mortality with increasing gestational age underscores the health risks averted by early rather than late abortion. At present, 11 percent of abortions are obtained after 12 weeks of pregnancy; these later abortions are obtained disproportionately by adolescents: for girls under age 15, 22 percent of abortions are done in the second trimester, whereas the comparable figure for women over age 20 is 9 percent (Rosenfield, 1994). Although late abortion may be due to delay in recognizing a pregnancy, in deciding what to do if the pregnancy is unwanted, or may be a consequence of a genetic defect not detected until the second trimester, public policies can also increase the chance that an abortion will be performed in the second rather than the first trimester. Policies that may discourage first-trimester abortions include mandatory waiting periods (now required in 13 states), parental involvement/judicial bypass laws (35 states), and various informed consent laws, many of which require that women be given antiabortion lectures and materials intended to discourage them from having an abortion (31 states) (National Abortion and Reproductive Rights Action League, 1994). Chapter 7 notes the important and related issues of insufficient training of providers in abortion techniques and of declining numbers of abortion providers.

Psychological Issues

Although the medical risks of abortion appear to be very small, the procedure may pose troubling moral and ethical problems to some women and providers as well. In addition, women (and those close to them) may find that confronting an unintended pregnancy and weighing the option of abortion are emotionally difficult experiences, and the procedure itself may involve appreciable pain and expense.

Accordingly, numerous researchers have attempted to determine the extent to which abortion results in psychological problems in the weeks and months following the procedure. Some have investigated what has been called "post-abortion syndrome," hypothesizing that abortion may lead to a form of posttraumatic stress disorder, even though abortion does not meet the American Psychiatric Association's definition of trauma (Gold, 1990). Most of the 250 studies dealing with the psychological effects of induced abortion suffer from substantial methodological shortcomings and limitations (Council on Scientific Affairs, 1992; Adler et al., 1990; Gold, 1990; Koop, 1989). In light of these problems, former Surgeon General C. Everett Koop concluded in 1989 that data "were insufficient…to support the premise that abortion does or does not produce a post-abortion syndrome." He also concluded that emotional problems resulting from abortion are "minuscule from a public health perspective" (Koop, 1989). Similarly, Adler et al. (1990:42) concluded that "studies [of the psychological impact of abortion] are consistent in their findings of relatively rare instances of negative responses after abortion and of decreases in psychological distress after abortion compared to before abortion."

Political Issues

It is important to add that even though the medical and psychological consequences of abortion for individual women are largely minor, the consequences for the nation's political and social life are less benign. The legality and availability of abortion have been associated with important and painful divisions throughout the country, even overt hostility and violence, including several murders of health care personnel working for clinics that provide abortions. Controversy over abortion has affected public discourse on a wide range of issues—health care reform, fetal tissue research, and public funding for contraceptive services and research, among other topics. Views about abortion have colored state and local elections, Supreme Court nominations, political conventions, presidential politics, and many other issues as well. Polling data show that although a majority of Americans continue to support the basic legality of abortion, there remain many differences of opinion about the extent to which abortion should be available without restrictions, the acceptability of using government funds to pay for abortions, whether parental consent should be required when a minor seeks an abortion, and other issues as well (Blendon et al., 1993). It appears that social and political controversy over abortion will likely remain a divisive force in the United States—a reality that underscores the importance of reducing unintended pregnancy, which is the principal antecedent to abortion.

Maternal Demographic Status

As noted in Chapter 2, unintended pregnancy occurs among all populations of women. But the experience is relatively more common in several specific groups: women at either end of the reproductive age span and women who are unmarried. Although many of these unintended pregnancies are resolved by abortion, an appreciable number result in live births (see Table 2-2). Therefore, in assessing the consequences of unintended pregnancy, it is useful to review the available data on the extent to which these demographic attributes themselves carry increased risks for children and their parents. Information on both socioeconomic and medical risks are reviewed below; because poverty is intertwined with the issues of both age and marital status, as subsequent text reveals, it is not discussed as a separate issue. Data from selected developing countries on many of these issues have recently been reviewed but are not presented here (National Research Council, 1989a,b).

This focus on selected groups is not meant to obscure a major point made in Chapter 2: although it is true that women who are unmarried or at either end of the reproductive age span are disproportionately represented among those having births that were unintended at conception, the majority of such births are to women without these attributes. Unintended pregnancy remains a widespread problem, whatever its pockets of concentration.

Adolescent Childbearing: Socioeconomic Issues

The negative associations between early childbearing and a host of economic, social, and health outcomes have been found in a variety of data sets over time. The association is strong, consistent, and persistent. The critical question has been that of causality. Births during the teenage years are concentrated among disadvantaged groups, whose members are likely to experience multiple disadvantages as adults whether or not they have children as teenagers. Thus, it has been argued that the association between early childbearing may reflect the disadvantaged backgrounds of those adolescents who become parents rather than any negative effects due to the timing of the birth itself (Geronimus, 1992; Luker, 1991).

Before addressing the causality issue, it is important to note the strong association of teenage childbearing with various problems. The link to diminished socioeconomic well-being, for example, for both children and their mothers has been recognized for several decades (Bacon, 1974). Adolescents who have children are substantially less likely to complete high school than those who delay childbearing. In recent years, the proportion of teenage mothers with high school degrees has increased, in large part because many are able to complete requirements for the general equivalency diploma (Moore, 1992; Mott

and Maxwell, 1981). However, few teenage mothers attend college, and less than 1 percent have been found to complete college by age 27 (Moore, 1992).

Moreover, teenage mothers are more likely to be single parents or, if they are married, to experience marital dissolution (Hayes, 1987). Indeed, the proportion of teenagers who are single parents has increased substantially over the years. For example, in 1970, 30 percent of all births to teenage girls occurred outside of marriage, whereas 67 percent of births occurred outside of marriage in 1991 (National Center for Health Statistics, 1994).

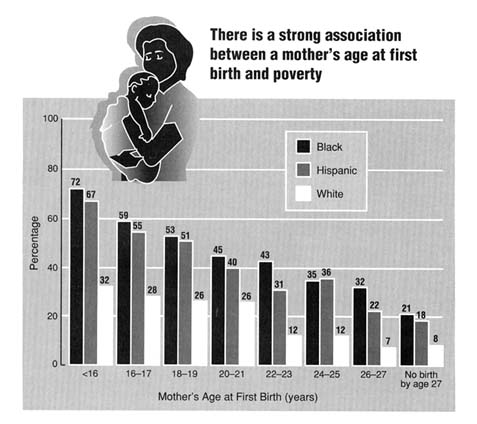

Larger families place greater demands on a family's economic assets. Although family sizes among younger as well as older mothers have declined over time, younger mothers continue to have more children than delayed childbearers (Moore, 1992). Because of their fewer years of schooling, larger families, and lower likelihood of being married, teenage mothers acquire less work experience, have lower wages and earnings, and are substantially more likely to live in poverty. Figure 3-1 illustrates the strong association between age at first birth and poverty. Although minority women generally face a higher probability of poverty regardless of their age at first birth, age at first birth is linked to lower economic well-being within each race/ethnicity group. A majority of Hispanic and black teenage mothers are poor; that is, the ratio of their family income to the poverty threshold is below 100 percent; less than one-fourth of women who delay childbearing into their 20s have such low incomes. Among whites, one-fourth of teenage mothers had family incomes below the poverty level, compared with less than 1 in 10 among delayed childbearers.

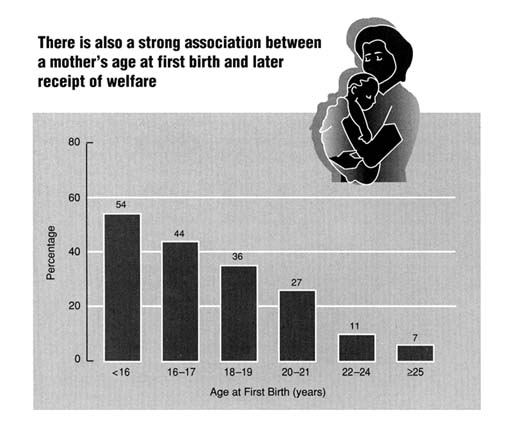

The lesser likelihood of marriage and lower earning capacity of teenage mothers are also related to more frequent welfare receipt. Figure 3-2 illustrates the very strong association between a mother's age at the birth of her first child and the probability that she will receive payments from Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) during her first-born's preschool years.

Again, though, there are important questions about whether these many associations are directly caused by the mother's young age. Untangling the question of causality is essential to understanding the impact of childbearing in adolescence on both the mother and her offspring and in designing remedial programs for the future. Specifically, if having a baby has no negative impact on socioeconomic status or health, then remedial efforts should focus less on delaying childbearing than on alleviating the disadvantages associated with and apparently contributing to teenage childbearing. Of course, for many service providers and policymakers confronted with the needs of young parents and their children, the causality issue is moot; teenage parents and their children represent a population with multiple and immediate needs who pose substantial public costs, and figuring out cause versus association has little urgency.

Selectivity into early parenthood has long been recognized (Waite and Moore, 1978), and researchers have employed a variety of strategies to control for the effects of socioeconomic background differences. For example, Moore

Figure 3-1

Percentage of mothers in poverty at age 27 by age at first birth. Source: Moore KA, Myers DE, Morrison DR, Nord CW, Brown B, Edmonston B. Age at first childbirth and later poverty. J Res Adol. 1993;3:393–422.

and colleagues (1993) estimated structural equation models including numerous background factors as controls; Hoffman et al. (1993) and Geronimus and Korenman (1992) compared outcomes for sisters, one of whom was a teenage mother and one of whom was not; Grogger and Bronars (1994, 1993) compared teenagers whose first birth was to twins with teens who had single births; and Hotz and colleagues are now comparing teens who have miscarriages with teens who deliver and raise their children (J. Hotz, pers. com., 1994).

Published results from these investigators find that the negative effects associated with teenage childbearing are much diminished when the mother's prepregnancy characteristics are accounted for. Nevertheless, virtually all researchers using varied approaches with varied data sets find that early childbearing is associated with negative outcomes over and above the effects of background. Put another way, there does appear to be a causal and adverse

Figure 3-2

Percentage of mothers ever receiving Aid to Families with Dependent Children in the first 5 years after first birth by age at first birth, 1979 cohort National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Source: Child Trends, Inc. based on public use files from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1979–1988 data, under Contract N01-HD-9-2919 from the National Institutes of Health.

effect of early childbearing on the health and social and economic well-being of children; this effect is over and above the important effects of background disadvantages.

Adolescent Childbearing: Medical Issues

In addition to the socioeconomic burdens accompanying childbearing by teenagers, adolescent pregnancy often poses serious health risks as well to both

mothers and infants. Young adolescents (particularly those under age 153) experience a maternal death rate 2.5 times greater than that of mothers aged 20–24 (Morris et al., 1993). Common medical problems among adolescent mothers include poor weight gain, pregnancy-induced hypertension, anemia, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and cephalopelvic disproportion (Stevens-Simon and White, 1991). It is also believed that teenagers are at greater risk of very long labor (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 1993), but whether this risk results in increased rates of labor abnormalities and cesarean deliveries has not been proven conclusively (Lubarsky et al., 1994). Less is known about the long-term physiological sequelae. Adolescent mothers tend to be at greater risk for obesity and hypertension in later life than older primiparas, but most studies have not clearly distinguished whether these conditions are linked to early childbearing or early maturation (Stevens-Simon and White, 1991).

Although potential risks to the adolescent mother are quite serious, the risks to the infant she delivers are even greater. Infants born to mothers less than 15 years of age are more than twice as likely to weigh less than 2,500 grams (about 5.5 pounds) at birth and three times more likely to die in the first 28 days of life than infants born to older mothers (McAnarney and Hendee, 1989). After controlling for birthweight, the postneonatal mortality rate is approximately twice as high for infants born to mothers under 17 years of age than for infants born to older women. The incidence of sudden infant death syndrome is higher among infants of adolescents, and these infants also experience higher rates of illness and injuries (Morris et al., 1993).

Many of these health risks derive from the demographic attributes of adolescents rather than from their physiological immaturity. For instance, pregnancy-induced hypertension appears to be connected more closely to low parity than to age. Several studies have indicated that very young adolescent mothers are underweight and give birth to smaller babies because of poor diets and inadequate or no prenatal care (Stevens-Simon and White, 1991). Similarly, the greater incidence of illness and injury in infants of adolescent mothers is more likely due to environmental factors such as poverty, poor health habits, and insufficient supervision than to the age of the mother per se (Stevens-Simon and White, 1991).

Childbearing at Older Ages: Socioeconomic and Medical Issues

Unfortunately, few data are available to help provide an understanding of the socioeconomic consequences to parents or children of childbearing late in life, and the consequences may well differ by parity. Older parents having a first or second child may be better educated, may be more likely to be married, and may have higher incomes than younger parents, especially those parents in their teens or early 20s. On the other hand, a birth occurring to an older mother can also be a higher-order birth—for example, a fourth or fifth child or more—whose addition to the family may add appreciable strain. Moreover, elderly parents may have less physical energy and perhaps less flexibility in outlook, despite the presumption of increased wisdom.

However, data are available to assess the important medical risks to the mother and her child that cluster at this end of the reproductive life span. In the aggregate, childbearing becomes riskier to both mother and infant as women get older. Maternal mortality rates are several times higher in women over age 40 than in younger women. From 1979 to 1986 the overall maternal mortality rate in the United States for women over age 40 was 56 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with only 9.1 deaths per 100,000 live births in the general population (Koonin et al., 1991). Maternal morbidity is also higher among women over 40 (Prysak at al., 1995). In a review of the literature on the effect that greater maternal age has on pregnancy outcome, Hansen (1986) found that the majority of studies show a two- to fourfold increase in the frequency of toxemia in older mothers compared with that in younger ones. Venous thrombosis, a serious condition usually occurring postpartum in 1 in 100 women, was reported in one study to occur in 1 in 12 women over age 40 (Lehmann and Chism, 1987). In addition, the incidence of chronic conditions that are aggravated by pregnancy, such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, increase with maternal age. Unless these conditions are monitored closely, they can pose major maternal as well as perinatal health risks.

Risks to the fetus and infant of a woman over age 40 include spontaneous abortion, chromosomal defects, congenital malformations, fetal distress, and low birthweight. Although the chances of miscarriage for a woman under age 25 are only 1 in 400, after the age of 35 the rate jumps to 40 in 100 pregnancies (Hotchner, 1990). Down syndrome, a chromosome disorder commonly associated with advanced maternal age, occurs at an approximate rate of 1 in 1,167 in pregnancies to women age 20; by age 40 the rate is 1 in 106 (Scott et al., 1989). It is believed that Down syndrome and other chromosomal disorders occur more frequently in older women because of their longer exposure to such environmental risks as X-rays and certain drugs. Medical conditions more common to older women affect their infants as well. For example, diabetes, if not carefully monitored, can lead to congenital malformations among other problems, and high blood pressure can cause fetal distress. Older women appear

to give birth more often to infants who weigh less than 2,500 grams and more than 4,000 grams, occurrences that are linked to biologic aging of maternal tissues and systems and/or the cumulative effects of disease (Lee et al., 1988). Low birthweight from growth retardation or prematurity is a risk factor for asphyxia, birth injuries, and susceptibility to infection (O'Reilly-Green and Cohen, 1993).

These various medical risks to the mother and infant are not always due to older age alone (Vercellini et al., 1993), although some may be, as noted above (Lee et al., 1988). It is more that as women age they have an increased chance of having a preexisting medical condition like diabetes or a long history of exposure to potentially harmful substances such as X-rays. And because these various conditions and factors can complicate pregnancy and childbearing, older women as a group are at increased risk of poor pregnancy outcome overall.

Childbearing by Single Women

Births resulting from unintended pregnancies are often conceived out of wedlock and the infants are born to unmarried women. More than 40 percent of infants born after unintended conception begin life with unmarried parents. Births to unmarried parents are twice as likely to be unintended as births to married parents (70.4 compared with 33.9 percent) (Kost et al., 1994). Moreover, couples who marry after conception—usually unintended—are more likely to divorce than couples who marry before conception (Bumpass and Sweet, 1989). Finally, unintended pregnancies within marriage are associated with a greater risk of divorce after the child's birth. For all these reasons, children born after unintended conceptions are very likely to live apart from one or both of their parents, usually their father, sometime during childhood.

A large body of research suggests that the absence of a father—either because of divorce or an out-of-wedlock birth—is associated with negative outcomes in children when they grow up. Although many children raised by single parents do very well and although many children raised in two-parent families develop serious problems, the absence of the father increases the risk of a number of negative outcomes. The increase in risk associated with father absence is about 1.5 to 2.5, depending on the outcome being studied (Grogger and Bronars, 1994; Haveman and Wolfe, 1994; McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994; Seltzer, 1994; Furstenberg and Cherlin, 1991).

Compared with children from the same social class background who grow up with both biological parents, children raised by only one parent, usually the mother, are more likely to drop out of high school, less likely to attend college, and less likely to graduate from college if they ever attend (Graham et al., 1994; Haveman and Wolfe, 1994; Knox and Bane, 1994; Wojtkiewicz, 1993; Sandefur et al., 1992; Haveman et al., 1991; McLanahan, 1985). According to one

nationally representative sample of young adults—the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY)—the high school dropout rate is 13 percent for children raised by two biological parents, compared with 29 percent for children raised by one or neither parent (McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994). Before leaving high school, children in one-parent households score lower on standardized achievement tests, have lower grade point averages, have more erratic attendance records, and have lower college expectations (Astone and McLanahan, 1991). These children also show more behavioral and emotional problems while growing up, as reported by parents and teachers (Thomson et al., 1994; Zill et al., 1993; Furstenberg et al., 1987).

Children raised by single mothers exhibit different patterns of home leaving and family formation. They leave home earlier than children in two-parent families (Kiernan, 1992; Thornton, 1991); they are more likely to become teenage parents and unmarried parents (Haveman and Wolfe, 1994; Wu and Martinson, 1993; McLanahan, 1988; McLanahan and Bumpass, 1988); and, if they are married, are more likely to divorce (McLanahan and Bumpass, 1988). Estimates from the NLSY show that the risk of becoming a teenage mother is 11 percent for children raised by both parents and 27 percent for children raised by single mothers (McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994).

Finally, children who live with only one parent have more problems finding and keeping a steady job after leaving school and are more likely to have encounters with the criminal justice system than children who live with both parents (Haveman and Wolfe, 1994; McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994; Powers, 1994). As noted above, these differences persist even after adjusting for differences in the parents' socioeconomic background.

The findings discussed above have been replicated with numerous data sets in the United States and by researchers in several other countries (McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994; Kiernan, 1992; Cherlin et al., 1991). They also have been examined by different statistical techniques to adjust for unobserved differences between families that break up and families that stay together (Haveman and Wolfe, 1994; Powers, 1994; Manski et al., 1992). Finally, the data have been replicated for children of different racial and ethnic groups and different social classes within the United States. The findings are quite robust across different samples, different countries, and different estimation techniques.

Although the risks associated with the absence of the father are similar for children from different backgrounds, the absolute effects are much larger for children from minority and economically disadvantaged families. This is because the underlying risk of dropping out of high school and becoming a teenage mother is much greater for these children than for children from white middle-class families. The average Hispanic child has a 25 percent chance of dropping out of high school if he or she lives with both parents and a 49 percent chance of dropping out if he or she lives with a single parent. For black children the

percentages are 17 and 30 percent, respectively, and for non-Hispanic white children, they are 11 and 28 percent, respectively.

Although the absence of the father has become increasingly common among children of all racial and ethnic groups and among all social classes, Hispanic and black children and children from economically disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely than white children and children from economically advantaged families to live apart from their fathers. Thus, even though all children in families in which the father is absent face an increased risk, the consequences fall disproportionately on children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Much of the research on children raised by a single parent does not distinguish between children born to unmarried parents and children whose parents experience a divorce or separation. In a few instances, however, researchers have been able to make this distinction and to compare children born outside marriage with children of divorced parents. Their findings show that once differences in parents' education and age are taken into account (on average never-married parents are younger and less educated than divorced parents), children born to unmarried parents are quite similar to children whose parents experience a divorce in terms of academic and social achievement (McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994; Thomson et al., 1994; McLanahan and Bumpass, 1988; McLanahan, 1985). Although some differences in outcomes among children with these two types of single parents have been observed, they are small compared with the differences between children raised by single parents and children raised by both of their biological parents.

The Effects of Intendedness

A number of investigators have studied whether children born as a result of unintended pregnancies (both mistimed and unwanted) are at greater risk of various poor outcomes, such as low birthweight, than are children born as a result of intended pregnancies. This section of the report reviews a complex set of studies on this topic, after first presenting some introductory comments on the methodological problems faced in analyzing the effects of intention status as a single variable. A limited amount of material about the effects of unintended pregnancy on the parents is also included.4

Methodological Concerns

Studies on the consequences of unintended pregnancies for the health and well-being of children and families have used a wide variety of data sources, study methods, and sample populations. They have also used numerous terms and concepts to sort out and classify the complex feelings that often surround a given conception. One source of information on the effects of intention status is the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), which was discussed in detail in Chapter 2. There, some of that survey's strengths and limitations were discussed, especially as regards its terminology. In this section of the report, many more data sources and studies are reviewed that pose their own methodological challenges. In general, though, the problems are similar to those faced by the NSFG: accurately determining parental attitudes at the time of conception, and classifying those attitudes. Because studies have used different techniques to solve these two problems, it is sometimes difficult to synthesize results.

Researchers studying the effect of intention status on various outcomes have approached the problem of determining parental attitudes at conception in a variety of ways. One strategy, employed primarily in a series of European studies, is to use the request for an abortion as a marker of an unintended or, more particularly, an unwanted pregnancy. These studies have assessed outcomes for pregnancies in women denied abortions. One difficulty with such studies lies in disentangling the effects of factors that might have led to the denial of the abortion from the unwantedness of the pregnancy itself.

Another strategy is to inquire after the fact about the intention status of a given pregnancy. Theoretically, such retrospective measurement of parental attitudes should be made as soon after conception as possible, in order to increase the accuracy with which intention status is recalled. However, it is difficult to obtain a representative sample of the pregnant population shortly after conception. Most studies that ask pregnant women about intention at the time of conception rely on clinic-based, not population-based, samples of women. This means that a selection bias is built in from the outset—that is, the sample is composed entirely of women already in prenatal care; those who are not in care, for whatever reason, are excluded. Thus, results cannot be generalized to those with late prenatal care or none at all.

The most representative studies of the impact of parental intention at conception are such population-based surveys as the NSFG. But in this survey, as noted in Chapter 2, months or even years have sometimes passed between conception and the measurement of attitudes at the time of conception. The extended time between conception and measurement of parental attitudes increases the uncertainty that parents will accurately recall their pregnancy intentions at conception.

When parental attitudes toward the conception are measured at delivery or postpartum, the accuracy of parental recall may also be affected by the outcome

of the pregnancy. Inaccuracies in recalling parental attitudes at conception are likely to bias studies toward a finding of no ill effect when there is a true effect. This is because people who did not originally intend the conception may be more likely to recall it as intended than are people who intended the conception to recall it as unintended (Ryder, 1979, 1976; Westoff and Ryder, 1977). Thus, when adverse effects are observed, they may be underestimates of the full impact of unintended pregnancy.

The second methodological problem faced in these studies is that classifications of intention status vary widely, which makes pooling their results particularly challenging. Different indicators of intendedness are often used across studies, and because many of them do not use questions identical or similar to those of the NSFG, it can be difficult to compare findings. Even small differences in methodology may create differences in estimates of mistimed and unwanted conceptions (see, for example, Kost and Forrest, 1995). In addition, some studies that assess the effects of intention status do not distinguish between mistimed and unwanted conceptions, the two types of pregnancies included under the umbrella term of unintended. When conceptions are lumped into a category of unintended conception, it cannot be determined whether there is a difference in pregnancy outcome between a mistimed or an unwanted conception.

This distinction is very important and bears once again on the issue of association versus causality that was noted above in the discussion of maternal demographic status. If it is clear that a negative effect is closely linked to unwanted pregnancy, it is not necessary to establish definitively whether the effect is caused by or merely associated with unwanted pregnancy. By preventing unwanted pregnancy (that is, helping couples to avoid pregnancies that they did not want at all), the ill effect will not occur, because no pregnancy or birth takes place. But with mistimed pregnancy, the distinction does matter. If it can be determined that the ill effect is caused by the pregnancy being mistimed, then there is some reason to hope that by helping couples to time their pregnancies better (which usually means postponing them), the incidence of the problem would decrease. If, on the other hand, the ill effect is merely associated with mistimed pregnancy, it is more likely that changing the timing of pregnancy would not affect the risk of the ill effect occurring. Thus, in reviewing studies on the effect of intention status on various outcomes, it is important (1) to distinguish mistimed from unwanted pregnancies, and (2) in the case of studies examining the effects of mistimed pregnancies on various outcomes, to consider whether the investigators have attempted to separate those effects that are associated with a timing failure from those that are caused by the timing failure. Because of this significant distinction, liberal use of italics is made in the balance of this section to distinguish between these two categories of unintended pregnancy. Also, where possible, comment is made on the causality/association issue.

Finally, it is important to note that the literature on the consequences of mistimed and unwanted conception spans three decades, during which time drastic changes occurred in couples' abilities to control their fertility. A cohort of parents in the early 1990s may look very different from a cohort in the 1960s, whose members were studied before the introduction of oral contraceptives, publicly funded family planning programs, or legalized abortion.

In summary, study results need to be interpreted in light of how well parental intentions were captured, that is, the degree to which the study may accurately reflect parental attitudes at conception, and the precision with which that measurement was made. Even with these inherent methodological problems and challenges, the literature in this area is nonetheless fairly coherent and compelling. It is summarized below by type of health behavior or condition examined (see also Appendix D).

Prenatal Care

In theory, there are many reasons why a woman faced with an unintended pregnancy might receive insufficient prenatal care. Ambivalence toward maintaining the pregnancy may lead to a delay in seeking prenatal care; time may be lost when women who are not intending to be pregnant do not recognize the symptoms of pregnancy. Or the youth and poverty that often accompany unintended pregnancy may make enrollment in prenatal care difficult. Regardless of the reasons for delaying care, the immediate costs to the woman and her developing fetus may be less vigilance in detecting problems such as pregnancy-induced hypertension, less support for practicing healthy behaviors such as smoking cessation, and less preparation for parenthood (Kogan et al., 1994).

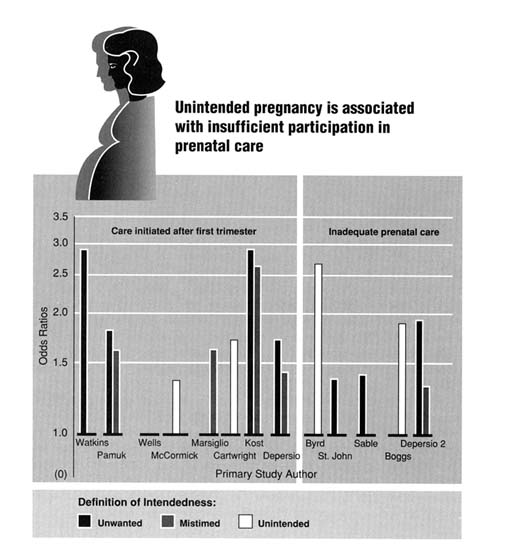

A substantial literature documents a relationship between unintended pregnancy and insufficient participation in prenatal care. Women who have mistimed or unwanted conceptions tend to initiate prenatal care later in pregnancy and to receive less adequate care (Figure 3-3) than women who have intended the pregnancy. When compared with women who planned to conceive, women with an unwanted pregnancy are 1.8 to 2.9 times more likely to begin care after the first trimester (DePersio et al., 1994; Kost et al., 1994; Pamuk and Mosher, 1988; Watkins, 1968). Women with mistimed conceptions are between 1.4 and 2.6 times more likely to begin care after the first trimester as are women who intended the conception (DePersio et al., 1994; Kost et al., 1994; Pamuk and Mosher, 1988). Studies that combine these women into a group with unintended conceptions report intermediate odds ratios of 1.1 to 2.6 (Byrd, 1994; Cartwright, 1988; Marsiglio and Mott, 1988; McCormick et al., 1987; Wells et al., 1987). These studies show a persistent pattern over time (from 1968 through 1993) and across diverse medical care and cultural settings

Figure 3-3

Studies of prenatal care attainment: odds ratios or relative risks of inadequate care by pregnancy intendedness. All rates displayed in this figure were developed by the Committee on Unintended Pregnancy from the published research except those for the DePersio study, which had already calculated the rates.

(e.g., women in England, black women in Harlem, Hispanic women in Houston, and representative samples of all U.S. women in the NSFG, the National Natality Survey, the NLSY, and the National Maternal and Infant Health Survey). When factors associated with both planning status and prenatal care initiation are controlled, the effect of mistimed or unwanted conception remains elevated, but its effect is reduced and sometimes no longer statistically significant (see tables in Appendix D). Thus, in most studies unintended pregnancy has been found to exert an additional barrier to the early initiation of prenatal care among women who are already at higher risk of later care.

The adequacy of prenatal care has been estimated by a combination of both early initiation and sufficient numbers of visits throughout pregnancy. In all of the relevant studies, a negative association between adequacy of prenatal care and desired or intended pregnancy is reported (Figure 3-3); the association may be more negative among unwanted than among mistimed conceptions. The association is attenuated when it is controlled for related factors. In particular, one study found that when the mother discussed her pregnancy with members of her support network or when she received support for the pregnancy from family members, the effect of mistiming on adequacy of prenatal care was no longer significant. Family support for obtaining care also reduced the effect of an unwanted conception on adequacy of care, but just discussing the pregnancy did not eliminate the effect (St. John and Winston, 1989). This suggests that a strong social support network may assist the pregnant woman in overcoming the barriers to obtaining care. Unfortunately, many women who find themselves with an unintended pregnancy lack such social resources.

Further evidence that intention to conceive is related to early access to prenatal care is provided in an examination of the impact of public funding of family planning services on the number of women seeking prenatal care after the first trimester. After controlling for the rate of publicly funded abortions, the ethnic and religious composition of the population, income, and female labor force participation, Meier and McFarlane (1994) found that for every additional dollar in state expenditures for family planning, there are significantly fewer births with late prenatal care. This study is discussed in more detail in Chapter 8.

Behavioral Risks in Pregnancy

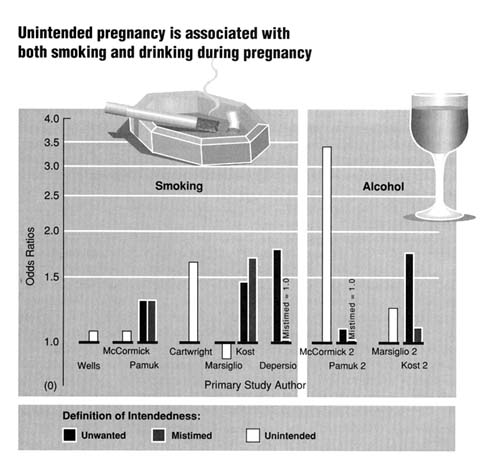

Women with unwanted or mistimed conceptions may need additional, sometimes intense, care and supervision during pregnancy. They are more likely to smoke and to drink (Figure 3-4). The effect of pregnancy intention on other behaviors associated with pregnancy outcome, such as illicit drug use, weight gain during pregnancy, and use of multiple vitamins, is not as well studied.

Population-based studies (national as well as in selected states) linking smoking to intention status among pregnant women date from 1980 and show remarkable consistency. Women with mistimed or unwanted conceptions are

Figure 3-4

Studies of behavioral risk factors: odds ratios or relative risks of behavioral risks during pregnancy. All rates displayed in this figure were developed by the Committee on Unintended Pregnancy from the published research except those for the DePersio study, which had already calculated the rates.

about 30 percent more likely to smoke than are women with intended conceptions (DePersio et al., 1994; Kost et al., 1994; Cartwright, 1988; Marsiglio and Mott, 1988; Pamuk and Mosher, 1988; McCormick et al., 1987; Wells et al., 1987). The odds ratios are similar for both black and white women (Pamuk and Mosher, 1988). Adjustment for factors related to both pregnancy planning and smoking tend to reduce the estimates of effect, but planning status remains a significant factor in most studies. These are probably underestimates of the true effect, because of misclassification bias resulting from underreporting of smoking and alcohol consumption.

Beyond the health risks that many of these behaviors pose, it is important to consider this broad area of behavior for other reasons as well. In particular, to the extent that there is a connection between unintended pregnancy and drug or alcohol use especially, there are legal implications to consider. The issues of drug-exposed infants and fetal alcohol syndrome have attracted increasing attention in recent years. Much of the increased caseload of the child welfare system in the 1980s has been attributed to drug and alcohol related issues. Moreover, there has been an effort in many states to address the use and abuse of alcohol and other drugs by pregnant women through the legal system by application of both criminal laws and child welfare laws, approaches that have both financial costs and personal costs associated with them.

Low Birthweight

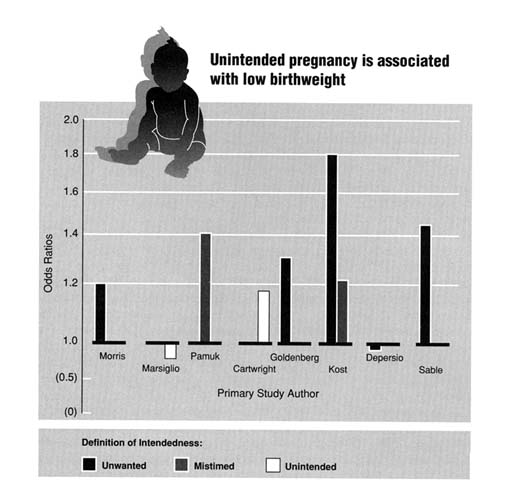

A number of researchers have examined the risk of delivering a low birthweight (<2,500 grams) infant following an unintended conception (Figure 3-5). Given the diversity of time and settings in which these studies took place, there is a surprising uniformity of results, with crude odds ratios for unwanted conceptions and for mistimed conceptions ranging from 1.2 to 1.4 (DePersio et al., 1994; Kost et al., 1994; Sable, 1992; Goldenberg et al., 1991; Cartwright, 1988; Marsiglio and Mott, 1988; Pamuk and Mosher, 1988; Morris et al., 1973). The data indicate that if all unwanted pregnancies were eliminated, there would be a 7 percent reduction in the low birthweight rate among black infants and a 4 percent reduction among white infants (Kendrick et al., 1990)—a change that would help to decrease the large disparity between rates of low birthweight among blacks and whites (Hogue and Yip, 1989). However, it is not clear that better timing would reduce the risk of low birthweight.

In the developing world, closely spaced births are associated with increased risk of infant mortality, and, less definitively, with increased risk of low birthweight (Haaga, 1989). In the United States and Norway, some studies have failed to find an increased risk of low birthweight for closely spaced births (Klebanoff M, 1988; Erickson and Bjerkedal, 1978). However, a recent prospective study suggests that white infants conceived within three months of a previous pregnancy and black infants conceived within nine months of a previous pregnancy are at greater risk of preterm delivery and low birthweight (Rawlings et al., 1995). To the extent that very closely spaced pregnancies are not planned (and clinicians have the strong impression that this is often the case), unintended pregnancy may increase the risk of low birthweight through this mechanism.

There have been a few studies of the components of low birthweight: preterm delivery (DePersio et al., 1994; DeMuylder et al., 1992; Goldenberg et al., 1991) and intrauterine growth retardation (Goldenberg et al., 1991). Although the data are sparse, they suggest that the association between pregnancy desire and low birthweight is through an increased risk of preterm delivery rather than through slowed fetal growth.

Figure 3-5

Studies of low birthweight: odds ratios or relative risks of low birthweight (<2,500 grams) by pregnancy intendedness. All rates displayed in this figure were developed by the Committee on Unintended Pregnancy from the published research except those for the DePersio study, which had already calculated the rates.

Infant Mortality

A link between unintended conception and infant mortality has been made using population-based data from a variety of sources and with a variety of methods. For example, using data from the NSFG and other surveys, it was estimated that if all sexually active couples had routinely used effective contraception in 1980, there would have been almost 1 million fewer abortions (533,000 rather than 1.5 million), 340,000 fewer live births that were unintended at conception, 5,000 fewer infant deaths, and a reduction in the infant mortality rate of 10 percent (World Health Organization, 1987). Another method to estimate the impact of unintended conception on infant mortality is to infer decreases in unintended pregnancies from changes in the characteristics of women giving birth. Using this methodology, about one-third of the decline in infant mortality between 1960 and 1968 was attributed to change in the distribution of live births by maternal age and birth order (Wright, 1975). A third method is to correlate changes in infant mortality over time with other temporal changes. Using this methodology, Grossman and Jacobowitz (1981) determined that between 1966 through 1968 and 1970 through 1972, the single most important factor associated with declining neonatal mortality (death in the first 28 days following birth) among both black and white infants was the increasing availability of induced abortion. Similarly, Joyce (1987) estimated that a decade later the reduced incidence of low birthweight and preterm births among black infants in 1977 was mostly associated with the availability of family planning clinics which helped women to avoid a birth unintended at conception.

More recent estimates of the impact of family planning and abortion services on low birthweight and infant mortality suggest continued benefit (Meier and McFarlane, 1994). Although the evidence of the public health value of current family planning programs argues for their continuation and expansion (Klerman and Klerman, 1994), the gap between existing services and the theoretical benefit of all conceptions being intended is enormous.

Poor Child Health and Development

To sustain normal health and development, children need a wide variety of resources that support cognitive stimulation and development, as well as affective and relational development. Baydar and Grady (1993) hypothesized that children born after mistimed or unwanted conceptions have fewer such resources. Using data from the NLSY, they tested this hypothesis for 1,545 children at two points in their development: at 0–2 and 3–5 years of age. The conceptions of approximately one-third of the children had been mistimed; about 5 percent of the conceptions had been unwanted. The study revealed significant deficits in the

developmental resources available to these children; however, those deficits were associated with the sociodemographic differences among the families in which wanted, mistimed, and unwanted conceptions occurred. When background characteristics were controlled, a few developmental effects of planning status remained significant. Before 2 years of age, children whose conceptions had been mistimed or unwanted exhibited higher levels of fearfulness and lower levels of positive affect. When they were of preschool age, they had lower scores on verbal development tests, even though they had no deficit of verbal memory. The authors hypothesize that this critical developmental skill is lagging because ''significant adults, particularly the mother may be less available" to the children (Baydar and Grady, 1993:14).

In the most extreme examples of unwanted conceptions—children born after women were denied abortions—various social development problems and relationship problems have been documented among children in Sweden (Forssman and Thuwe, 1981, 1966; Blomberg, 1980; Hook, 1975, 1963), Finland (Myhrman, 1988), and Czechoslovakia (Kubicka et al., 1994; David et al., 1988; Matejcek et al., 1978). All studies compared children born to women denied abortions (DA group) with children born to women with accepted pregnancies (AP group). Children in the first group were found to be less well adjusted socially, more frequently in psychiatric care, and more often found in criminal registers. In all but the Czechoslovakian study, the deficits of children born after their mothers had been denied abortion could have been due to the less favorable family environments in which they were raised. However, Matejcek and colleagues (1978) also compared the DA group with siblings in both AP and DA families when the original cohort was 35 years of age. They found that the siblings did share some of the less favorable characteristics within the DA group, but DA females were more frequently emotionally disturbed than their AP female controls whereas their female siblings did not exhibit emotional deficits. Girls were also at a greater disadvantage in the Finnish study by Myhrman (1988), but in the Czechoslovakian group earlier problems were more pronounced among male offspring. In all groups studied, differences attenuated with increasing age, but they did not disappear, even by the time the children were in their 30s.

In severe situations of financial and emotional deprivation, children whose conceptions had been mistimed or unwanted may be at higher risk of physical abuse or neglect (Zuravin, 1991). One controlled, prospective study of physical abuse supports this hypothesis (Altemeier et al., 1979), although three retrospective studies do not (Zuravin, 1991; Kotelchuck, 1982; Smith et al., 1974). Four other studies of children of parents reported for abuse or neglect found higher numbers of such families with children whose pregnancies had not been intended than among families with no reports of abuse or neglect (Murphy et al., 1985; Oates et al., 1980; Egeland and Brunnquell, 1979; Hunter et al., 1978). In a study that separated abused from neglected children and that included

family size as a control variable, Zuravin (1991) found that unintended conception increased the risk of subsequent child abuse. Large family size, regardless of planning status, increased the risk of child neglect. On the basis of this and other analyses, Baumrind (1993:76), in a comprehensive study for the National Academy of Sciences, concluded that a child abuse prevention network should begin with "affordable contraceptive services." This echoes a previous analysis conducted for Surgeon General Koop, which stated that "the starting point for effective child abuse programming is pregnancy planning" (Cron, 1986:10). These research findings and perspectives also imply that by increasing the risk of child abuse and neglect, unintended pregnancy may increase the pressures on the child welfare system, including juvenile courts, the foster care system, and related social service agencies.

Consequences for the Parents

The birth of a child is a major event in parents' lives, regardless of whether the child was the result of an intended or unintended conception. When childbearing occurs without prior planning and preparation, it can cause severe disruption to other life plans, decreased resources for children already born, temporary or permanent lowering of educational and career aspirations, and a threat to present and future economic security. Its effects can be surprisingly far-reaching, contributing, for example, to the problem of insufficient child care in the United States. Child care is a major burden, largely for women, often beginning with teenagers who stay home from school to care for their infants and children (who are often the result of unintended pregnancies), but extending beyond that to older women, both married and single, who are unable to support themselves and their families because they cannot pay for or find adequate care for their children.

In particular, mistimed and unwanted pregnancies can place a strain on parental relationships. Marriages that begin after an unintended conception have a higher chance of failure, regardless of whether the marriage is a first or a second one (Wineberg, 1992, 1991; Teachman, 1983; Card and Wise, 1978; Furstenberg, 1976). The young age of the spouses does not entirely explain this observation, because it is found for second as well as first marriages.

Mothers

Worldwide, childbearing at very young or very old age, the bearing of many children, and the bearing of children who are closely spaced (less than two years apart) contribute to the high level of maternal deaths (about 500,000 per year) and to the reproductive complications that women suffer (National Research Council, 1989a,b; Zimicki, 1989). Even in the United States, where maternal

mortality is low, pregnancy and childbirth carry risks, albeit small, of permanent disability and death (Franks at al., 1992; Atrash et al., 1990). A reduction in unintended pregnancies would reduce those risks, especially among women at highest risk of maternal morbidity and mortality, who are also the most likely to have an unintended pregnancy.

Current reports provide little systematic assessment of women's health following pregnancy and childbirth, but some data suggest that unintended pregnancy increases health risks for women. For example, unintended pregnancy can increase the likelihood of depression during pregnancy (Orr and Miller, 1995), and, regardless of marital status at birth, women who give birth following an unintended conception are more likely to suffer from postpartum depression as well (Salmon and Drew, 1992; Najman et al., 1991; Condon and Watson, 1987). They may also be at greater risk of experiencing domestic violence. For example, in a study done in New Zealand, 13.4 percent of women who experienced an unintended pregnancy also experienced physical violence from their partners over a 6-year period after conception; for those women who experienced intended pregnancies, the rate was 5.4 percent (Fergusson et al., 1986).

Data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS)5 are available on domestic violence during pregnancy and pregnancy planning for four states: Alaska, Maine, Oklahoma, and West Virginia (Gazmararian et al., 1994). Of the 12,612 women surveyed, physical abuse was reported among between 3.8 and 6.9 percent of them, depending on the state. Experience of violence was reported among between 5.6 and 10.7 percent of women with an unintended pregnancy.

Fathers

Very little is known about the impact of unintended childbearing on the fathers involved. The few studies of adolescent fathering and educational attainment have found an association between teenage fathering and dropping out of high school. However, those studies have not been able to determine whether problems in school lead to early parenting or whether early parenting increases the likelihood of dropping out of school (Parke and Neville, 1987; Marsiglio, 1986; Lerman, 1985; Card and Wise, 1978). Similarities in acting-out behavior among male students who had fathered, those who had caused a pregnancy that did not end in birth, and those who were unsure if they had caused a pregnancy suggest that educational and emotional problems precede rather than follow the

act of fathering (Resnick et al., 1993). These groups of young men were similar to each other but differed significantly from students who reported no involvement in causing a pregnancy.

Even less is known about the impact of unintended conception on the father's employment, but the scant available evidence suggests that there is less of an effect of early parenting on males than on females (Card and Wise, 1978). This is undoubtedly related to the greater responsibility that mothers assume in child rearing (Parke and Neville, 1987). "[T]o the extent that the adolescent father disassociates himself from the child and/or the mother, he may minimize the negative impact of early paternity on [his] own social or educational trajectories" (Parke and Neville, 1987:166).

An intriguing and important finding is that the ability of the father to provide "positive parenting" (i.e., positive involvement with one's child) may be strongly associated with whether the pregnancy was intended. Positive parenting is a benefit for the parent as well as the child. When the parents are unmarried, the father's involvement with his children may be limited by his own choice or by the mother's or her parents' functioning as gatekeepers to limit his contact (Parke and Neville, 1987; Parke and Beitel, 1986; Parke and Tinsley, 1984). Limited opportunities to learn about child development can affect a father's ability to parent effectively (Parke and Neville, 1987). Even married, adult fathers vary in their ability to achieve positive, significant involvement with their children (Cooney et al., 1993). When compared with younger fathers, men who became fathers after age 30 were more likely to be involved in a positive way with their children. Late parenting may more often reflect "intended parenting," with more time to prepare for the paternal role (Cooney et al., 1993:214).

Preconception Care

Another consequence of unintended pregnancy—the fourth reviewed in this chapter—is that opportunities for the mother and couple to engage in preconception risk assessment and intervention are often lost. The importance of preconception care derives from the notion that if a woman or couple is actively planning—or intending—a pregnancy, there are new and important opportunities to improve outcomes for both the mother and her baby by identifying and managing risks before conception. Most women enter prenatal care several weeks into the pregnancy, even with the most earnest attempts to initiate care after missing one, and sometimes two, menstrual periods. Meanwhile, the conceptus has completed a critical interval that includes uterine implantation, organogenesis, and early system development. For the health care provider, this means that the length of care for such patients is 7 or 8 months at best, with no opportunity to have influenced fetal development during the first 1 or 2 months.

Certain specific diagnostic and clinical interventions become less effective or appropriate in later pregnancy; even more important, the opportunity for prepregnancy planning, including emotional preparation, has disappeared.

To understand the possible impact of preconception knowledge and care on reproductive behavior, and therefore to understand the opportunity lost by unintended pregnancy, it is important to review the content, promise, and limitations of preconception care. A number of authorities and professional groups have published recommendations for the content of preconception care (Cefalo and Moos, 1995; March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, 1993; Jack and Culpepper, 1990; Public Health Service Expert Panel on the Content of Prenatal Care, 1989). These recommendations have a high degree of commonality and for the most part focus on optimizing the woman's health and identifying pregnancy risks and negative habits that may influence fetal development. The approach involves active patient participation, individualized management plans, and a commitment to educational needs addressing both medical and psychosocial issues. Topics typically addressed in preconception care include diet and weight, exercise, smoking, use of alcohol and drugs, stopping contraception, identifying and reducing environmental risks (such as exposure to toxoplasmosis), evaluating vaccination history and immunity status, managing pelvic inflammatory disease and various STDs, if present (including chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes simplex virus, syphilis, HIV infection, and AIDS), and managing such medical conditions as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

The need for attention to these issues is supported by a study that collected data on the planning status of the births of over 12,000 women and on certain aspects of the women's behavior in the months preceding conception and during the first few weeks of pregnancy—smoking, drinking, being underweight, or delaying initiation of prenatal care (Adams et al., 1993). The investigators found that, even using a relatively narrow definition of need for preconception care, 38 percent of the women had risk profiles that suggested the potential value of such intervention; for women whose pregnancies were unintended, the percentage was higher; for women whose pregnancies were intended, it was lower. To date, however, no large-scale prospective intervention trial has conclusively demonstrated the health benefits to mother or child from a broad program of preconception counseling and care.

For several specific medical problems, however, there is strong evidence that initiating care before conception is critical to both infant and maternal well-being. For example, maternal diabetes is associated with teratogenic and other complications of pregnancy; strict metabolic control both before and during pregnancy has been shown to reduce the risk to the developing fetus. Fuhrman and colleagues (1983) followed 420 pregnant women with insulin-dependent diabetes. Of these women, 292 began strict metabolic control after 8 weeks of pregnancy; among the infants born to this group, 22 had congenital malformations,

yielding an incidence rate of 7.5 percent. The other 128 women began strict metabolic control before conception; only one infant was born with a congenital malformation, yielding a 0.8 percent incidence rate. Other studies confirm the importance of pre- and periconceptional metabolic control (Fuhrman et al., 1984; Ylinen et al., 1984; Miller et al., 1981).

Similarly, current data suggest that the risk of neural tube defects (NTDs), such as spina bifida, may be decreased when folic acid is consumed before conception and through the early months of pregnancy. The Medical Research Council Vitamin Study Research Group (1991), which examined the value of folic acid supplementation around the time of conception, showed a 72 percent protective effect among a group of women at risk of a recurrence of fetal NTD—a finding that led, among other things, to the Centers for Disease Control recommendation that women with a history of NTDs who are planning another pregnancy take 4 milligrams of folic acid daily beginning 1 month before conception and continuing through the first 3 months of pregnancy (Centers for Disease Control, 1991). Although some controversy exists regarding the utility of peri-conceptional administration of folic acid to prevent NTDs in women with no history of such problems, the U.S. Public Health Service has recommended the use of folic acid by all women to reduce the chances of NTDs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1992).

Unintended pregnancies also mean that individuals may not be able to take the fullest advantage of the explosion of research in human genetics. A recent Institute of Medicine (1994) report explores the broader social implications of advances in the ability to detect genetic diseases, advances that are emerging from the Human Genome Project in particular. When completed, the project will make it possible to detect more diseases—some that are uniformly fatal early in life as well as some that emerge later in life and that are not as life-threatening or for which treatments are or will become available. In addition, it will increasingly be possible to identify an individual's carrier status. Such increased genetic knowledge holds promise for reducing the emotional pain, trauma, and expense that genetic defects can cause families; it also carries the possibility of decreasing the need for second-trimester abortion, which remains one of the major options available to couples who learn that their developing fetus carries a serious genetic defect—knowledge that often is available only after many weeks of gestation are completed.6

Preconception assessment and care, including attention to genetic risk, is not only a woman's issue. Data from laboratory animals in particular suggest that reproductive outcomes are also affected by the male's preconception health status and behavior (Davis et al., 1992). In a comprehensive review of various influences on spermatogenesis and male fertility—spanning nutrition, alcohol and drug use, medical history, exposure to chemicals, and related areas—Cefalo and Moos (1995:240) conclude that involving men in preconception care is important not only for identifying particular risks to male reproductive success but also for encouraging "cooperation and support between the prospective father and mother" in anticipation of pregnancy and then beyond.

For the full potential of preconception intervention to be realized, however, access to such care will need to be more widespread than it is at present, and provider training will need to be increased. Too often, preconception care is an advantage of the privileged few whose private insurance or personal finances make such care affordable and accessible. For many of the women who might benefit the most from preconception care, such as those with a history of poor health maintenance or abuse of alcohol or drugs, it remains only a theoretical benefit that is rarely available and perhaps not even understood.

The Demographic Implications of Reducing Unintended Pregnancy

This section suggests how the profile of the childbearing population in the United States would change if unintended pregnancies were eliminated altogether. Such a statistical exercise helps in understanding the consequences of current demographic patterns of unintended pregnancy and subsequent childbearing.

Data presented earlier in this chapter and in Chapter 2 indicate that the incidence of childbearing from unintended pregnancies is higher among unmarried than married women; it has also been shown that, on average, risks of poor outcomes are greater for children of one-parent families than children of two-parent families. Furthermore, the risks of poor child outcomes are particularly high when the child is born to a woman who wanted no children at all or no more children (i.e., a birth from an unwanted pregnancy). It follows from these observations that reducing the proportion of births derived from unintended pregnancies could have a significant impact on the well-being of children in U.S. society by increasing the proportion of children who are the products of intended pregnancies to married mothers.

|

|

the opportunity to plan perinatal and pediatric management. |

How much of a change in children's family contexts could possibly be achieved by reducing the number of births derived from unintended pregnancies? To address this question, information on the relationship between maternal marital status and whether births resulted from unwanted or mistimed pregnancies (using data on births from the 1982 and 1988 NSFG) was applied to the estimated proportion of births to unmarried women in 1994. Births from unwanted and mistimed pregnancies figure differently in this estimation. Births from unwanted pregnancies, by definition, would simply not occur, whereas births that were mistimed at conception would occur, but would occur later—some in marriage and some not. Logit simulation was used to model this redistribution of mistimed pregnancies, as described in more detail in Appendix E.

The results of this simulation show that eliminating unintended pregnancy decreases dramatically the proportion of children who are born to unmarried women. Specifically, the proportion of all births in 1994 that were either to unmarried women or were the result of an unwanted pregnancy would decrease from 38 to 21 percent—a 45 percent reduction overall. The percentage of all births to teenage mothers would also decrease, given the disproportionate representation of teenagers in the pool of unmarried women giving birth, but the precise shape of the age redistribution was not calculated.

The complete elimination of all unintended fertility is an unrealistic goal. However, this statistical exercise adds to the evidence presented earlier in this chapter that an appreciable reduction in the number of unintended pregnancies would improve the well-being of future generations. The fact that other industrialized countries report fewer unintended pregnancies than the United States suggests that progress in the desired direction is a realistic, feasible goal.

Conclusion

The data and perspectives presented in this chapter demonstrate that unintended pregnancy has serious consequences. these consequences are not confined only to unintended pregnancies occurring to teenagers or unmarried women and couples; in fact, unintended pregnancy can carry serious consequences at all ages and life stages. First, unintended pregnancy often leads to abortion, a fact that underscores a point made at the outset of this report: reducing unintended pregnancy would dramatically decrease the incidence of abortion. Although it is quite clear that abortion has few if any long-term negative consequences on a woman's medical or psychological well-being, it is nonetheless true that resolving an unintended pregnancy by abortion may be an emotionally difficult experience for a woman and others close to her; in particular, abortion providers, women, and their partners as well may find that abortion poses difficult moral or ethical problems; and there continue to be

major political and social tensions, including violence and even murder, associated with abortion in the United States.

Second, a disproportionate share of the women bearing children who were unintended at conception are unmarried and/or at either end of the reproductive age span. These demographic attributes themselves carry increased medical and social burdens for children and their parents. At the same time, it is important to reiterate that although women who are unmarried and/or at either end of the reproductive age span are disproportionately represented among those having births that were unintended at conception, the majority of such births are to women without these attributes (Chapter 2).

Third, a complex and extensive group of studies has attempted to measure the impact of a pregnancy's intention status on a wide variety of child and parental outcomes. These studies show that unintended pregnancies—especially those that are unwanted (as distinct from mistimed)—carry appreciable risks for children, women, men, and families. That is, unintendedness itself poses an added, independent burden beyond whatever might be present because of other factors, including the demographic attributes of the mother in particular. For an unwanted pregnancy, prevention of ill effects on the child is not dependent on whether the unintendedness itself caused the negative outcome. If the unwanted pregnancy can be prevented, any associated ill effects will also be prevented.

With an unwanted pregnancy especially, the mother is more likely to seek prenatal care after the first trimester or not to obtain care. She is more likely to expose the fetus to harmful substances by smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol. The child of an unwanted conception is at greater risk of weighing less than 2,500 grams at birth, of dying in its first year of life, of being abused, and of not receiving sufficient resources for healthy development. The mother may be at greater risk of physical abuse herself, and her relationship with her partner is at greater risk of dissolution. Both mother and father may suffer economic hardship and fail to achieve their educational and career goals. The health and social risks associated with a mistimed conception are similar to those associated with an unwanted conception, although they are not as great.