Appendix A—

Enrollment and Employment Trends in Geography

The Association of American Geographer's (AAG's) Employment Forecasting Committee1 prepared the following analysis of present and future enrollment and employment trends for geographers at the request of the Rediscovering Geography Committee. The Employment Forecasting Committee's analysis was published in the August 1995 issue of the Professional Geographer and is reprinted here with the permission of the AAG and Blackwell Publishers.

Employment Trends in Geography, Part 1: Enrollment and Degree Patterns *

Patricia Gober

Arizona State University

Amy K. Glasmeier

Pennsylvania State University

James M. Goodman

National Geographic Society

David A. Plane

University of Arizona

Howard A. Stafford

University of Cincinnati

Joseph S. Wood

George Mason University

This paper is the first in a series of three papers dealing with the current and future labor market for geographers. It is based on a report prepared by the Association of American Geographers' (AAG) Employment Forecasting Committee to the National Research Council's (NRC) Rediscovering Geography Committee. This report provides a data-based analysis of the past and future supply of geographers, the current labor market conditions in the field, and the factors likely to influence the future demand for geographers (faculty hiring, geographic education initiatives, trends in private sector jobs, etc.).

Each year some 4,000 individuals receive degrees in geography from America's institutions of higher education. They, or some portion of them, make up the new supply of geographers entering the labor market. In the near future (up to five years), the availability of new geographers is related to the number of geography students now in the educational pipeline. Their current specialties, and the specialties of the programs from which they come, tell us about the types of skills and the kinds of interests to be held by future labor force entrants. In the longer term (five to ten years), the number of new geographers will be influenced by geographic education initiatives at the precollegiate level. More and better geographic instruction in elementary and secondary schools will expose more students to geography as a field of study and as a potential career path. The purposes of this paper are to (1) review degree and enrollment trends in geography, (2) assess the "trickle-up" effects of geographic education initiatives at the precollegiate level, and (3) investigate the characteristics of future supply as evidenced by the types of occupations for which geography departments are now preparing students.

Background

Previous attempts to examine employment trends in geography focused on the academic job market (Hart 1966, 1972; Hausladen and Wyckoff 1985; Suckling 1994; Miyares and McGlade 1994) or relied exclusively on AAG membership data (Goodchild and Janelle 1988; Janelle 1992). Early "manpower" studies by John Fraser Hart matched predictions of the future supply of new doctorates in geography with estimates of new teaching jobs in colleges and universities and developed scenarios of surplus and deficit in the academic labor market. Hausladen and Wyckoff examined age profiles of topical and areal specialties from the 1982 AAG Directory with an eye toward predicting the effects of future retirements on the field. More recent investigations by Suckling and by Miyares and McGlade focused on the demand side of the employment equation and examined changes in the number, rank, location, and specialties of jobs advertised in Jobs in Geography.

Michael Goodchild and Donald Janelle analyzed trends in the intellectual structure of the discipline as manifest in AAG specialty group membership and topical proficiencies. Goodchild and Janelle's findings provided valuable insights into changes in the nature of geographic thought and training. Technical expertise and interest in geographic information systems (GIS) were burgeoning, especially among young geographers, while regionally oriented

specialties were shrinking. Reliance on AAG membership data, however, limits the applicability of these studies to college and university professors and their students—individuals who make up about two-thirds of the AAG's membership but a relatively small share of the total number of new geographers entering the labor market.

Degree and Enrollment Trends

The National Center for Education Statistic's (NCES) annual Digest of Education Statistics is the most accurate guide to the number of degrees granted in geography in the United States. Published continuously since 1948-1949, these data are compiled from questionnaires returned by each institution of higher education in the United States. Geography is listed as a separate field within the larger category of the "social sciences." Although not all individuals who receive degrees in geography directly enter the labor market for geographic skills (some go on to graduate school and others seek employment in occupations unrelated to geography), this series is the most sensitive barometer available of the supply of new geographers.

The NCES series reveals a surge in geography degrees granted in the late 1960s and early 1970s as the first wave of the baby boom generation began to graduate from colleges and universities, as a higher proportion of young people sought access to higher education, and as amendments to the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) in 1964 bolstered graduate enrollments (Fig. 1). Possible factors specific to geography include curricular reforms in the form of the High School Geography Project and Commission on College Geography and emerging technological advances in remote sensing and quantitative techniques that created opportunities for geographers outside of education. The number of bachelor's degrees peaked in 1971-1972 at 4,300, the number of master's one year later at almost 800, and Ph.D.s one year after that at 217.

From their high point in the early 1970s, the number of geography degrees declined slowly but steadily. At their nadir in 1987-1988, the number of new geographers entering the labor market was just two-thirds what it had been 15 years earlier. This downward pattern was not due to trends in higher education as a whole, as the total numbers of bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees in the United States grew steadily during the late 1970s and early 1980s,

Figure 1:

Geography degrees awarded, 1951-1992.

despite declines in the traditional college-age population (NCES 1993a).

A turnaround in the number of geography degrees conferred at the undergraduate and masters levels began in 1988. Subsequently, the discipline has outpaced higher education as a whole in the increase in bachelor's and master's degrees granted. Between 1988-1989 and 1990-1991, the number of bachelor's degrees in geography grew by 13% compared with 7% for all fields. The number of master's degrees in geography grew at a rate of 14% compared with 9% for all fields. New Ph.D. holders in geography remained steady while the number of doctorates overall increased by 10% (NCES 1993a). The most recent figures for 1991-1992 show explosive growth at the bachelor's level and continued growth at the master's. Several factors are probably responsible for the renewed vigor in geography's degree production at the bachelor's and master's levels. They include rising public concern with environmental and international problems, greater attention to geographic education at the precollegiate and collegiate levels, and technological advances in GIS that provide new geographers with highly marketable skills.

Increases in the number of geography degrees are broadly consistent with trends in the social sciences, where the number of degrees fell consistently and dramatically from the early 1970s through the mid-1980s (Fig. 2). After 1987, degrees conferred in the social sciences in addition to geography, including anthropology, economics, political science, and sociology, rose sharply. Recent growth in the social sciences has been linked to the shift away from business majors, rising concern over the environment and crime, the growing elderly and homeless populations, and the increasingly competitive global economy (Bureau of Labor Statistics 1994, 120). The increased presence of women and minorities on university campuses also has been associated with the growth in social science fields (NCES 1993a). In the late 1980s female-dominated fields like education, psychology, and the social sciences experienced faster-than-average growth while slower-than-average growth occurred in traditionally male-dominated areas such as business

Figure 2:

Degrees in geography, social sciences, physical sciences, and life sciences, 1971-1991.

and management, engineering, and the physical sciences.

The physical sciences, including the closely related fields of geology and meteorology in addition to astronomy, chemistry, and physics, experienced steady degree production throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. The number of graduates sharply declined after 1985, especially at the bachelor's level (Fig. 2). The decline in new degree holders has been attributed, in part, to the fact that students are not obtaining in the high schools the demanding math and science background that is necessary for pursuing a university degree in the physical sciences (National Science Board 1993). The life sciences grew rapidly during the early and mid-1970s, declined steadily during the 1980s, and then turned upward in the late 1980s, at about the same time that the number of degrees in geography began to rise.

Geography's pattern of degree production during the past 20 years reflects, in part, the patterns of its closely related fields. Geography's early losses were similar to, but not as severe as, those for the social sciences as a whole. The discipline's upturn during the late 1980s is mirrored in both the social and life sciences categories. Ironically, the experience of the physical sciences correlates with geography's but in an inverse fashion. The physical sciences grew slightly during the late 1970s and early 1980s at the same time that geography declined. They reached their peak at about the time that geography reached its low point in the late 1980s. In recent years, the number of geography degrees has increased while the number of physical science degrees has declined.

Enrollments in geography programs provide another picture of labor supply conditions in the field, although the connection between supply and enrollment is less direct than the association between supply and degrees granted. Enrollment figures are unreliable, particularly at the undergraduate level. Some students are forced by institutional rules to declare their majors before they have settled on a career path. Others change majors, but these changes are not reflected in institutional accounting systems. As a result, enrollment figures are best seen as a general guide to current and future trends in the field.

The most complete record of graduate enrollments in geography programs comes from the NSF (1993). These data reveal that graduate enrollments in geography dipped about 10% from 1981 through 1985 but rose steadily thereafter (Fig. 3). This pattern fits with trends in geography graduate degrees, which bottomed out three years later in 1988 but are now on the rise. It also suggests that the upturn in master's degrees, from 555 in 1990 to 622 in 1991 and 639 in 1992, is not an aberration but the harvest of healthy enrollment growth during the late 1980s.

Geography's pattern is roughly parallel to that of the social science category, although the discipline's early-decade decline in enrollments was less severe and its late-decade rebound was more pronounced. Predictably, trends for the social sciences are smoother because they even out the ebbs and flows of individual disciplines. Graduate enrollments in the environmental sciences, including the atmospheric sciences, the geosciences, and oceanography, rose steadily until mid-decade, declined during the late 1980s, and began to climb again after 1989.

Geography's late-decade burst in enrollments was unmatched by individual fields in the social and environmental sciences. From their low point in 1985, graduate enrollments in geography grew by almost one-third by 1991 (Table 1). Student interest in sociology, anthropology, and political science was strong but not equal to the rise in geography. Enrollments in economics changed little. The poor performance of the category of environmental sciences between 1985 and 1991 was primarily the result of the dismal performance of the geosciences (geology), which comprises more than one-half of the enrollment in the environmental sciences category. Declines in the domestic oil and gas industry and mineral exploration drastically reduced the demand for geologists. The U.S. Geological Survey, the major government employer of geologists, and individual state surveys also downsized during this period.

Recent increases in graduate geography enrollments should translate into an increasing supply of highly trained geographers entering the labor market in the near future. Indeed, because 1991 is the most recent year for which

Figure 3:

Graduate enrollment in geography, social sciences, and environmental sciences, 1981-1991.

we have graduate enrollment data, that added supply of graduate-level geographers probably is occurring already.

To obtain information about trends in undergraduate enrollments and, hence, the future supply of bachelor's-level geographers, we examined the number of "students in residence" in the Guide to Programs of Geography in the United States and Canada from 1986-1987 through 1993-1994. We eliminated those schools for which we were unable to obtain a complete record of enrollment data because we wanted to conduct a longitudinal investigation of how a constant set of schools performed through time rather than to obtain a series of cross-sectional studies of an ever-changing mix of programs. This elimination process reduced the number of schools to 174 from the 239 listed in the 1993-1994 Guide. The list of 174 includes 51% of all bachelor's-granting departments, in 1993-1994, 88% of the master's departments, and 85% of the doctoral programs; thus, the experience of graduate departments will be overrepresented in the overall tallies. The average bachelor's-granting department contained 71 undergraduate students in residence, master's departments had 93, and doctoral departments had 104. If the missing cases display the same size patterns as the schools for which we have continuous data, they contain about 33% of the enrollment in undergraduate geography programs nationwide, and the 174 departments that form the basis of the study contain approximately two-thirds of geography's undergraduate enrollment.

The number of undergraduate students in residence in the 174 departments for which continuous data are available grew by 47% from 1986-1987 to 1993-1994. When these enrollment figures are normalized to their 1986-1987 levels and then viewed alongside the undergraduate degree figures discussed earlier, the two patterns are highly consistent (Fig. 4). Given that enrollments, as reported by the 174 schools in our study set, are a

Table 1 Graduate Enrollments in Geography and Related Fields, Fall 1985 to Fall 1991

|

Field |

1985 |

1991 |

Percent Change 1985–1991 |

|

Geography |

2,836 |

3,785 |

33.4% |

|

Social Sciences |

70,450 |

81,279 |

15.3 |

|

Anthropology |

5,631 |

6,695 |

18.8 |

|

Economics |

12,430 |

12,709 |

2.2 |

|

Sociology |

6,567 |

8,314 |

26.6 |

|

Political Science |

27,012 |

31,929 |

18.8 |

|

Environmental Sciences |

15,591 |

14,747 |

–5.4 |

|

Atmospheric Sciences |

964 |

968 |

.4 |

|

Geosciences |

10,294 |

7,626 |

–25.9 |

|

Oceanography |

2,081 |

2,293 |

10.2 |

|

Source: National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Studies. Academic Science/Engineering: Graduate Enrollment and Support, Fall 1991. |

|||

reasonably accurate guide to degrees granted in geography, it is logical to expect the accelerated enrollment in geography programs after 1992 to translate into higher degree production in 1992-1993 and 1993-1994.

Enrollment gains varied in a predictable fashion by region (Table 2). They were slower than the national average of 47% in the Northeast and Midwest, regions experiencing sluggish population growth and slow growth in student enrollments generally. Faster-than-average growth in enrollments was recorded in the South and West, areas of rapid population growth, net domestic in-migration, and immigration from abroad. The latter two regions accounted for almost two-thirds of the increase in geography enrollments nationwide.

Enrollment data also reveal that geography programs in Ph.D.-granting departments were the biggest generators of undergraduate enrollment increases. Between 1986-1987 and 1993-1994, enrollments increased by a stun

Figure 4:

Normalized undergraduate geography enrollments and degrees, 1987-1994.

Table 2 Undergraduate Enrollments by Region and Type of Geography Program

|

|

1986–1987 |

1993–1994 |

1986–1987 to 1993–1994 |

|

Total enrollment |

10,743 |

15,752 |

46.6% |

|

Region |

|||

|

Northeast |

1,839 |

2,453 |

33.4 |

|

Midwest |

3,057 |

4,261 |

39.4 |

|

South |

2,662 |

4,169 |

56.6 |

|

West |

3,185 |

4,869 |

52.9 |

|

Type of program |

|||

|

Undergraduate |

2,224 |

3,339 |

50.1 |

|

Masters |

5,196 |

7,095 |

36.5 |

|

Doctoral |

3,323 |

5,318 |

60.0 |

|

Source: Authors' calculations based on analysis of AAG Guide to Programs of Geography in the United States and Canada (1986-1987 to 1993-1994). |

|||

ning 60% in Ph.D. departments, compared with 50% in undergraduate departments and 37% in master's programs. This finding probably reflects the growing emphasis on undergraduate education in major research universities nationwide.

The NCES has projected rates of growth in the number of degrees for higher education as a whole to the year 2002-2003 (NCES 1993b). Applying these rates to geography assumes that the discipline will reflect the trends prevalent in all of higher education. Our track record relative to these national norms, unfortunately, is not good. The number of degrees granted in geography declined throughout most of the 1970s and 1980s even though the total number of degrees granted by all fields grew. Moreover, since geography began its rebound in 1988, it has outpaced higher education as a whole in the number of degrees granted. NCES projects aggregates rather than individual disciplines or areas (social sciences, education, engineering, physical sciences, etc.) for precisely this reason. Some fields grow while others stagnate. Students "vote with their feet," moving easily and quickly among fields in response to changing labor market conditions, social values, and personal preferences (i.e., the recent experience of geology). Projections using 1985-1986 as a base year would have, for example, seriously overestimated degrees and enrollments in the physical sciences and underestimated those in the social sciences.

Nevertheless, we applied projections for higher education as a whole to geography (Table 3). We envision these projections as a benchmark against which we can assess the discipline's future performance rather than as hard-and-fast expectations. The numbers of undergraduate degrees in higher education are expected to rise until the mid-1990s, hold steady until 2000, and then increase again early in the next decade. Applying these projections to geography anticipates an increase in undergraduate degrees from 3,397 posted in 1990-1991 to 4,080 in 2002-2003.

The previous discussion of degree and enrollment trends in the field, however, suggests much faster growth in the number of geography undergraduate degrees. The figure for 1991-1992 was already above 3,800. Furthermore, if 13,701 "students in residence" in geography programs generated 3,808 degrees in 1991-1992, then the undergraduate enrollment figure of 15,752 in 1993-1994 should translate into 4,378 bachelor's degrees in that year, far more than higher education trends indicate for the entire projection period extending to 2002-2003.

Higher education projections are also problematic at the graduate level because more undergraduate degrees filter up through the system and generate more master's and Ph.D. degrees. Throughout the 1980s, the ratio of bachelor's to master's degrees hovered between 5 and 6 (Fig. 5). Assuming this ratio holds firm (and we have a long historical record to suggest that it will), we expect that the number of master's degrees will rise to 800 in 1993-1994, again a far larger figure than an extrapolation of higher education trends would indicate.

Because of their relatively small number, Ph.D. degrees vary more from one year to the next. Since 1980, the ratio of bachelor's to Ph.D. degrees has ranged from 22 to 29, averaging 25 (Fig. 5). Using this average ratio of

Table 3 Projections of Bachelor's, Master's, and Doctoral Degrees in Higher Education and Geography, 1990–1991 to 2002–2003

|

Bachelor's Degrees |

|||

|

|

Higher Education |

|

Geography |

|

1990–1991 |

1,084,000 |

|

3397 |

|

|

(+86,000) |

7.93% |

(+270) |

|

1995–1996 |

1,170,000 |

|

3667 |

|

|

(+15,000) |

1.28% |

(+46) |

|

1999–2000 |

1,186,000 |

|

3714 |

|

|

(+117,000) |

9.86% |

(+366) |

|

2002–2003 |

1,303,000 |

|

4080 |

|

Master's Degrees |

|||

|

|

Higher Education |

|

Geography |

|

1990–1991 |

337,000 |

|

622 |

|

|

(+17,000) |

5.05% |

(+31) |

|

1995–1996 |

354,000 |

|

653 |

|

|

(–1,000) |

–.28% |

(–2) |

|

1999–2000 |

353,000 |

|

651 |

|

|

(+12,000) |

3.40% |

(+22) |

|

2002–2003 |

365,000 |

|

673 |

|

Doctoral Degrees |

|||

|

|

Higher Education |

|

Geography |

|

1990–1991 |

40,000 |

|

119 |

|

|

(+1,100) |

2.72% |

(+3) |

|

1995–1996 |

41,100 |

|

122 |

|

|

(+500) |

1.22% |

(+1) |

|

1999–2000 |

41,600 |

|

123 |

|

|

(+200) |

.48% |

(+1) |

|

2002–2003 |

41,800 |

|

124 |

|

Source: Gerald, D.E., and W.J. Hussar, 1993. Projections of Education Statistics to 2003. National Center for Education Statistics. |

|||

25 and an estimated 4,378 bachelor's degrees, we expect the number of Ph.D. degrees to be 175 in 1993-94.

To confirm the validity of these expectations, we asked departmental chairs, individuals who are at the front lines of enrollment management in colleges and universities, to assess past and future trends in numbers of undergraduate degrees. We heard back from 214 of the 376 chairs to whom we sent questionnaires, for a response rate of 57%. This overall response rate was composed of rates of 76% for institutions offering the Ph.D. in geography, 58% for schools offering master's degrees, and 49% for other institutions. Included in the latter category are some two-year institutions and schools without full-fledged geography departments. Many are part of a bureaucratic unit whose chair or director is probably not a geographer and, thus, far less likely to respond to highly specific questions about the training and occupational prospects of geography students. Our sample, therefore, under-represents the views of the chairs whose programs account for a small proportion of the total number of geographers produced by institutions of higher education in the United States.

Chairs reaffirmed the sizable increases in degrees granted during the last five years (Table 4). Some 58% noted some increase in degrees over the last five years. Moreover, a majority of chairs were bullish about the prospects for future growth. When asked to assess the change in the number of geography degree graduates 6-10 years from now, 45% predicted increases between 10 and 25% and another 16% envisioned increases of more than 25%.

Departmental chairs also anticipate growth in the size of their graduate student bodies. Compared with the 1993-1994 academic year, chairs anticipated that graduate enrollments would climb 3% at the master's level and 9% at the doctoral level by 1998-1999.

Geographic Education Initiatives

To gain yet another perspective on the future supply of geographers, we asked several key Geographic Alliance Coordinators to com-

Figure 5:

Ratios of bachelor's to master's degrees and bachelor's to doctoral degrees in geography, 1951-1992.

ment on the ''trickle-up" effects of geographic education initiatives. To what extent, in other words, has the enhanced visibility of geography at the precollegiate level translated into more collegiate geography majors who will, in turn, constitute the future supply of new geographers? Interviews with A. David Hill from Colorado, Sidney R. Jumper from Tennessee, and Richard G. Boehm from Texas helped us to develop both a quantitative and a qualitative picture of these trickle-up effects. Keep in mind we are working from case studies of the success stories—states where Alliance efforts have been in place for some time, where geography is required for admission to the state's flagship universities (Colorado and Tennessee) or where it is part of the recommended high school program (Texas), and where the overall visibility of the discipline is high.

Tennessee provides us with a quantitative picture of what happened to high school geography enrollments in an environment that was favorable to geographic education. In 1982-1983, 5,535 students took world geography courses in Tennessee high schools. In 1986 the Tennessee Geographic Alliance was formed, and in 1989 the University of Tennessee added a "world geography or world history" admission requirement. By 1989-1990 world geography enrollments had soared to 18,487, and by 1992-1993, the last year for which we have data, they reached 28,733. Sidney Jumper, Geographic Alliance Coordinator and departmental chair at the University of Tennessee, reports that the increased presence of geography at the secondary level has affected the University of Tennessee's Department of Geography in a number of important ways. First, the department has gone from no incoming freshman majors each year to eight in 1992-1993 and four in 1993-1994. Second, undergraduate courses (service courses as well as those in the major) are oversubscribed. Third, the quality of students in the undergraduate program has improved, not so much as a result of better preparation, but from the fact that better students are now choosing geography as a field of study. And finally, the department

Table 4 Chairs' Estimates of Past and Future Changes in the Number of Geography Degree Graduates

|

|

Change in Last 5 Years |

Change 6-10 Years from Now |

||

|

Large increase (more than 25%) |

37 |

(18.7%) |

32 |

(15.8%) |

|

Modest increase (10–25%) |

77 |

(38.9%) |

91 |

(45.0%) |

|

Fairly stable (+/–10%) |

71 |

(35.9%) |

41 |

(20.3%) |

|

Modest decrease (10–25%) |

9 |

( 4.5%) |

9 |

( 4.5%) |

|

Large decrease (more than 25%) |

3 |

( 1.5%) |

1 |

( .5%) |

|

Unable to say |

1 |

( .5%) |

28 |

(13.9%) |

|

Total |

198 |

(100.0%) |

202 |

(100.0%) |

|

Source: Departmental chairs' survey. |

||||

was the only unit in the University's College of Arts and Sciences to gain a new position in 1993-1994. Jumper attributes this in part to the department's ability to demonstrate community outreach in the form of geographic education activities.

The story is similar in Colorado. Although high school enrollments are not available there, we do know that 78 of 150 school districts in the state instituted geography classes in the past five years, many in response to the inclusion in 1988 of a geography requirement in the University of Colorado's admission standards. Effects at the university level were an increase in the number of incoming freshmen geography majors, more undergraduate majors overall (from 107 in 1988 to 175 in 1992), an avalanche of new students (1,000 per semester) in an introductory geography course used to fulfill the admissions deficiency in geography, and a new faculty line targeted to provide instruction in this introductory course.

Texas Geographic Alliance Coordinators also describe an increase in majors and in freshmen taking geography courses. At Southwest Texas State University (SWTSU) the number of incoming freshmen geography majors, a barometer of geography's presence in high schools, increased from zero in the fall of 1983 to 29 in the fall of 1993. The number of incoming freshmen taking geography courses also increased over the same period, from 30 to 250. According to Richard Boehm, chair of the SWTSU geography department, the preparedness of these new students has not changed appreciably. What has changed is their heightened awareness of geography as a field of study and as a potential career path. Trickle-up effects also extend to the graduate level at SWTSU, as Boehm reports recruiting ten geography teachers into the department's master's program.

These case studies suggest that college and university geography departments will feel the effects of geography's higher profile at the precollegiate level. From a labor market perspective, more enrollment leads to more majors (the vast majority of geography majors come indirectly to the discipline after taking and enjoying an introductory geography course), more majors mean more degrees, and more degrees generate an ever-larger pool of people with geography backgrounds seeking employment.

Before we extrapolate these forces to all states and all geography departments, however, it is important to remember that we picked several of the most active and successful Alliance departments. In addition, the widespread adoption of the Geography National Standards, the key to diffusing these success stories nationally, is anything but assured. In the most optimistic scenario, the standards will be widely adopted and implemented, and the Tennessee, Colorado, and Texas success stories will diffuse across the nation, stimulating continued growth of new majors and, eventually, new geographers entering the work force. In the less optimistic scenario, other states will be unable to repeat these experiences, adoption of the National Standards will be limited, and the number of future geographers will level off.

Future Supply Characteristics

Numbers alone do not tell the full story of future supply conditions in geography. What types of skills and interests do students now in the educational pipeline have? We asked departmental chairs about tracks or specializations in their undergraduate programs and the types of occupations for which their students were being prepared. Of the 212 geography

chairs who responded to our survey, 139, or 65%, reported that their departments had at least one specialization. These specializations were led by programs in environmental/resource management, techniques (GIS, cartography, and remote sensing), and urban planning. These tracks appear to be designed to prepare students for the occupations in which geographers traditionally have found work rather than to develop their interests in regional geography or the systematic specialties like urban, economic, or physical geography that have traditionally formed the core of the academic discipline.

We also asked chairs to indicate the specific occupations for which students were being prepared (Table 5). The occupations indicated by the highest numbers of departments were (1) GIS/remote sensing specialist, (2) secondary school teacher, (3) cartographer, (4) environmental manager/technician, and (5) urban/regional planner. When chairs were asked to estimate the percentage of students in their programs who were preparing for particular occupations, a slightly different set of occupations emerges. Although GIS was by far the most popular occupational trajectory (involving almost 11% of students enrolled in programs offering GIS training), it was followed by environmental manager/technician and urban/regional planner. Although training as a secondary school teacher and cartographer, two of geography's long-standing career paths, were offered in a larger number of departments, these occupations involved a smaller share of currently enrolled students. In other words, whereas future teachers and cartographers are being trained in most departments, relatively few departments have high percentages of students preparing for these occupations.

Summary and Conclusions

Analysis of degree and enrollment trends in geography reveals the discipline's up cycle from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, its down period from the mid-1970s to around 1988, and its current rejuvenation. Data from a wide range of sources tracking a variety of indicators point consistently to significantly larger numbers of undergraduate majors and degrees and graduate majors and degrees during the early 1990s. To the extent that the number of geography majors and geography degree recipients correlates closely with labor force entrants, it is clear that the supply of new geographers has risen dramatically in recent years.

The evidence also supports continued growth in the supply of new geographers. The increasing numbers of students currently en

Table 5 Occupations for which Geography Students are Being Prepared (As Reported by Departmental Chairs)

|

Occupation |

Number of Programs Preparing Students for This Occupation |

Median Percent of Program's Students |

|

GIS/Remote Sensing Specialist |

172 |

11% |

|

Teacher-Secondary |

157 |

6 |

|

Cartographer |

156 |

7 |

|

Environmental Manager/Technical |

153 |

8 |

|

Planner—Urban/Regional |

152 |

8 |

|

Planner—Environmental |

148 |

8 |

|

Earth Scientist |

124 |

6 |

|

Teacher—Collegiate |

122 |

4 |

|

Teacher—Primary |

119 |

4 |

|

Climatologist/Meteorologist |

118 |

2 |

|

Community Development Specialist |

116 |

1 |

|

International Specialist |

109 |

3 |

|

Planner—Transportation |

106 |

2 |

|

Aerial Photo Interpreter |

102 |

2 |

|

Ecologist |

98 |

4 |

|

Land Economist/Real Estate Professional |

98 |

1 |

|

Marketing Analyst |

95 |

1 |

|

Administrator/Manager |

88 |

4 |

|

Soil/Agricultural Scientist |

86 |

1 |

|

Writer/Journalist/Editor |

82 |

1 |

|

Other |

33 |

12 |

rolled in undergraduate geography programs should translate into larger graduate enrollments and degrees granted. Widespread implementation of the Geography National Standards would mean more incoming geography majors, a heightened awareness of geography as a field of study, and generally more students taking geography courses. It appears that the discipline is doing a very successful job attracting new students who have come to see geography as a stepping stone to a satisfying and productive career. The obvious next question involves the extent to which these students are, in fact, finding work in the field. The second article in this series describes current labor market conditions for new geographers. •

Literature Cited

Bureau of Labor Statistics. 1994. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Bulletin 2450. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Goodchild, M.F., and D.G. Janelle. 1988. Specialization in the structure and organization of geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 78:1-28.

Hart, J.F. 1966. Geographic Manpower: A Report on Manpower in American Geography. Commission on College Geography Report 3. Washington, DC: Association of American Geographers.

Hart, J.F. 1972. Manpower in Geography: An Updated Report. Commission on College Geography Report 11. Washington, DC: Association of American Geographers.

Hausladen, G., and W. Wyckoff. 1985. Our discipline's demographic futures: Retirements, vacancies, and appointment priorities. Professional Geographer 37:339-43.

Janelle, D.G. 1992. The peopling of American geography. In Geography's Inner World, eds. R.F. Abler, M.G. Marcus, and J.M. Olson, 363-90. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Miyares, I.M., and M.S. McGlade. 1994. Specializations in "Jobs in Geography." Professional Geographer 46:170-77.

National Center for Educational Statistics. 1993a. Digest of Education Statistics: 1993. NCES 993-292. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

National Center for Educational Statistics. 1993b. Projections of Education Statistics to 2003. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

National Center for Education Statistics. 1994. Digest of Education Statistics: 1994. NCES 94-115. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

National Science Board. 1993. Science and Engineering Indicators: 1993. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

National Science Foundation. 1993. Academic Science/Engineering: Graduate Enrollment and Support, Fall, 1991. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Suckling, P.W. 1994. National and regional trends in "Jobs in Geography." Professional Geographer 46:164-69.

Employment Trends in Geography, Part 2: Current Demand Conditions*

Patricia Gober

Arizona State University

Amy K. Glasmeier

Pennsylvania State University

James M. Goodman

National Geographic Society

David A. Plane

University of Arizona

Howard A. Stafford

University of Cincinnati

Joseph S. Wood

George Mason University

This paper, the second in a series dealing with employment trends in geography, focuses on current labor market conditions. Two windows on the current labor market are (1) the employment experiences of recent graduates of geography programs and (2) the activities of the Association of American Geographers Convention Placement Services (CoPS). The former provides a perspective primarily on the nonacademic labor market in geography and includes bachelor's, master's, and doctoral recipients of geography degrees. The latter covers both academic and nonacademic jobs but focuses on geographers who hold advanced degrees.

Recent Graduates

Very little is known about the interface between postsecondary education and the labor market in geography. There is not a definite point where people leave the university and enter the work force. Many students work full- or part-time while they attend the university, others continue their educations after receiving an undergraduate degree, and still others take time off before they begin their professional careers or work in occupations completely unrelated to their undergraduate degree program. Complicating matters further, in geography, direct paths into the labor force are not as evident as in disciplines like nursing, accounting, engineering, and other professional fields. The vast majority of geographers work in occupations that do not carry the title "geographer."

Recognizing how little we know about the labor market for individuals with bachelor's and master's in geography, we queried recent graduates of a random sample of geography programs about their labor market experiences. Are they finding work? What types of occupations are they engaged in and for what kinds of employers do they work? Are they making effective use of the skills obtained in their geography programs? Whenever possible, we linked the results of the survey to national datasets on educational outcomes in order to provide a contextual and comparative perspective for geography's experience.

We chose a random sample of U.S. geography programs from the Guide to Programs of Geography in the United States and Canada stratified by region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) and type of department (bachelor's, master's, and doctoral). One bachelor's, master's, and doctoral department was chosen from each of the four major regions for a total of 12 geography programs.1 Departmental chairs provided us with lists of all graduates for calendar years 1990 through 1993. We mailed questionnaires to all 1,239 individuals on the lists and sent follow-up reminder postcards to those we had not heard from in two weeks. Our efforts yielded a total of 623 replies, 460 of them bachelor's recipients, 132 master's, 25 doctoral, and 6 unknown. Adjusting our population by the 38 questionnaires that could not be delivered by the U.S. Postal Service and for 16 respondents who turned out to be pre-1990 graduates, the overall response rate was a very respectable 53% (Table 1). The numbers in

Table 1 Response Rates by Geography Program

|

|

Surveys Sent |

Undeliverable/ Pre–1990 Graduates |

Valid Responses |

Response Rate |

|

Dartmouth |

77 |

0 |

44 |

57.1% |

|

Towson State |

146 |

2 |

70 |

48.5 |

|

Rutgers |

85 |

8 |

50 |

64.1 |

|

IPUPI |

33 |

3 |

16 |

53.3 |

|

Miami (Ohio) |

63 |

4 |

30 |

50.1 |

|

Iowa |

124 |

6 |

51 |

43.2 |

|

Jacksonville |

36 |

2 |

14 |

41.2 |

|

SWTSU |

392 |

11 |

200 |

52.5 |

|

George Mason |

92 |

8 |

53 |

63.1 |

|

Sonoma State |

54 |

4 |

29 |

58.0 |

|

Montana |

44 |

2 |

27 |

64.3 |

|

Hawaii |

93 |

4 |

43 |

47.7 |

|

Total |

1239 |

54 |

623 |

52.6 |

the subsequent tables may not sum to 623 because not all of the respondents answered all of the questions.

We asked graduates about their current employment status and determined that 416 (68.7%) were working full-time, 37 (6.0%) were working part-time, 12 (2.0%) were in the military, 96 (15.6%) were going to school and working, 19 (3.1%) were going to school and not working, 19 (3.1%) were unemployed, and 9 (1.5%) were out of the labor force. Compared to national norms that apply to bachelor's recipients only, geography's recent bachelor's graduates were somewhat less likely to be engaged in full-time employment and more likely to be in school. We view this comparison with considerable caution, however, because the National Center for Educational Statistics' (NCES) employment categories are different from ours (NCES 1993). The NCES puts teaching and research assistants into a category called "enrolled in school" and considers them not to be in the labor force. This rule assumes that a student's primary activity is going to school. Moreover, it assumes that the jobs held by students are available only to those attending school and not to the labor force in general. Our categories allowed students (including graduate assistants) to specify whether they worked or not, thus acknowledging that individuals can be students and labor force members simultaneously. Although our categories are more complicated, they better reflect the increasingly fuzzy distinction between educational and employment status.

Among bachelor degree recipients, we discovered that more of the earlier than later graduates were employed full-time, fewer were employed part-time, and fewer were unemployed (Table 2). The trend in the percent in school is quite typical. There is an initial surge by those who go directly from a bachelor's to a master's program, then a falling off followed by an increase about two years out. This is a big decision point for many, and a commitment to return to school comes at about this time. The small numbers of unemployed may be deceiving because the hard-core unemployed are unlikely to respond to a survey such as ours.

Overall, these results suggest that geography graduates, like many of their counterparts in the arts and sciences, experience a period of transition and adjustment between the time they receive their undergraduate degrees and the point at which they settle into stable, full-time employment. This period is characterized by the pursuit of additional education, part-time employment, and internships. A typical career path for the new graduate in today's job market may involve temporary, contractual employment on a project-by-project basis during which the individual makes contacts with local planning agencies and consulting firms. Experiences gained through a series of these temporary or contractual arrangements often lead to full-time employment within several years. Although verification of this hypothesis awaits careful longitudinal analysis that follows a panel of recent graduates through their early work careers, our data are suggestive of such a pattern.

Differences in employment status by year of graduation probably do not result from varying labor market conditions. College graduates throughout the study period faced equally

Table 2 Employment Status of Bachelor's Degree Recipients by Year of Graduation

|

|

Total (N=423) |

1990 (N=85) |

1991 (N=94) |

1992 (N=115) |

1993 (N=127) |

|

Percent employed |

76.1% |

83.6% |

76.6% |

78.3% |

69.3% |

|

Full time |

68.6 |

76.5 |

72.3 |

67.8 |

62.2 |

|

Part time |

4.7 |

1.2 |

3.2 |

7.0 |

6.3 |

|

Military |

2.8 |

5.9 |

1.1 |

3.5 |

.8 |

|

Percent in school |

19.7 |

15.3 |

20.2 |

15.6 |

25.3 |

|

And working |

15.4 |

12.9 |

14.9 |

13.9 |

18.9 |

|

And not working |

4.3 |

2.4 |

5.3 |

1.7 |

7.1 |

|

Percent unemployed |

3.1 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

4.3 |

3.9 |

|

Percent not in labor force |

1.2 |

0 |

2.1 |

1.7 |

.8 |

|

Source: Recent graduates survey. |

|||||

harsh employment prospects. If anything, conditions improved somewhat for the 1993 graduates. Nonetheless, this group was less settled than earlier cohorts into long-term careers. Nor is it likely that the recent increase in geography graduates described in the first article in this series has tightened the competition for jobs in the field to any measurable extent. The growth in degree holders is geographically widespread, and geographers represent but a small minority of applicants in any of the submarkets in which they compete.

To evaluate the occupational structure of geography degree recipients, we developed a list of 21 occupations with which we believed most geographers would identify and asked the respondents to indicate which occupation best applied to them. We also gave the option of an "other" category to accommodate those whose occupations were not well described by any of the items on our list. We judiciously recorded geographically oriented occupations from the "other" category into the categories into which we thought they best fit so that we would be left with an "other'' category that contained only those occupations that are far removed from the field. For the most part, these jobs were professional in nature, including minister, social worker, insurance underwriter, financial analyst, lawyer, and pilot, but they also included less-skilled positions such as van driver, waiter, and secretary. For all degree recipients (bachelor's, master's, and doctoral), approximately one-third of those who were employed and who listed an occupation were engaged in jobs that are not closely identified with geography. The fact that two-thirds of the respondents were employed in fields directly related to geography is an encouraging figure in an era when many college graduates are working in occupations that do not even require a college degree and the vast majority of social science graduates are employed outside their areas of study.

The proportion of new geographers at the bachelor's level holding positions in closely related fields is high by social science standards. During the early 1990s, only 16% of social science bachelor's degree recipients nationwide were employed full-time in jobs closely related to their fields of study one year after graduation (NCES 1993). Among our 1993 graduates, this figure was 38%, and for many of them, a full year had not elapsed since graduation. Our estimate of geography's figure was higher than for arts and sciences disciplines as a whole (26%) but lower than the norm for professional and technical fields (48%) (NCES 1993).

Much of the preceding discussion isolated the experience of bachelor's degree recipients in order to draw connections to national datasets. The subsequent analysis grouped together all degree levels. Even with 623 respondents, we do not have a sufficient sample size to allow meaningful disaggregation by degree levels. At this point, we seek a general understanding of the types of jobs that geographers hold irrespective of their degrees.

Among those who were employed and listed occupations closely related to geography, respondents clustered into five predictable occupations: teacher (15.6%), environmental manager/technician (12.9%), GIS/remote sensing specialist (10.5%), cartographer (8.2%), and planner (6.7%) (Table 3). The categories correspond quite closely to the most common occupations for which current students are preparing (as reported in the survey of departmental chairs in Part 1 of this series), although GIS/remote sensing specialist ranked higher on the list of occupations for which current

Table 3 Recent Graduates (All Levels) by Occupation

|

|

Number |

Percent |

|

Aerial photo interpreter |

5 |

.9% |

|

Administrator/manager |

15 |

2.7 |

|

Cartographer |

46 |

8.2 |

|

Community development specialist |

2 |

.4 |

|

Demographer/population researcher |

7 |

1.2 |

|

Earth scientist |

14 |

2.5 |

|

Ecologist |

8 |

1.4 |

|

Environmental manager/technician |

73 |

12.9 |

|

GIS/remote sensing specialist |

59 |

10.5 |

|

International specialist |

5 |

.9 |

|

Land economist/real estate professional |

6 |

1.1 |

|

Marketing analyst |

11 |

2.0 |

|

Planner—environmental |

16 |

2.8 |

|

Planner—urban/regional |

14 |

2.5 |

|

Planner—transportation |

8 |

1.4 |

|

Teacher—primary |

17 |

3.0 |

|

Teacher—secondary |

26 |

4.6 |

|

Teacher—collegiate |

45 |

8.0 |

|

Writer/journalist/editor |

3 |

.5 |

|

Other |

184 |

32.6 |

|

Total |

564 |

100.0 |

|

Source: Recent graduates survey. |

||

students are preparing than on the list of where recent graduates are working. These five categories (or aggregates of categories in the case of teaching and planning) accounted for 54% of the respondents who listed their occupations and 80% of those who chose from the list of geographically oriented occupations.

In terms of employers, the breakdown was 34% in government (local, state, and federal), 40% in the private sector, 17% in educational institutions, and the remainder in nonprofit organizations (Methodist Church, NAACP, health and social services, environmental groups, etc.) and as self-employed consultants and small-business owners (Table 4). When respondents were disaggregated by how directly their work relates to geography, the private sector emerged as the dominant employer of those working at the margins and outside of the field. Still, some 45% of those respondents reported an occupation closely related to their geographic training. Graduates working in government and education were the most likely to be involved in geographic occupations.

We cross-classified type of employer by occupation to gain a clearer picture of kinds of work geographers do for different types of employer (Table 5). Cartographers were concentrated in the federal government and, to a lesser extent, in private industry. Environmental managers worked in state government, supervising the myriad new environmental regulations, and in the private sector for environmental consulting firms that have been established to meet these regulations. Some 44% of the GIS/remote sensing specialists worked in the private sector. Planners were strongly clustered in local and, to a lesser extent, in state government. Not surprisingly, teachers were employed in educational institutions. Our residual category of other geographic professions was more concentrated in the federal government, nonprofit organizations, and self-employed settings than the respondents as a whole.

The strong association between the "other" category and the private sector can be interpreted in three ways. The standard interpretation is that some geographers are unable to find work or are uninterested in working in the field after graduation and therefore seek out or settle for private sector positions not traditionally associated with the discipline. A second perspective is that we have defined the notion of geographic occupations much too narrowly. Individuals who can use, display, and analyze geographic information to solve spatial and environmental problems can find jobs in all kinds of businesses, many with job titles that have not traditionally been associated with the field. Geography plays to the creativity, diversity, and flexibility of the contemporary labor market as much as it fills the standard niches of cartographer, planner, environmental manager, GIS/remote sensing specialist, and

Table 4 Recent Graduates (All Levels) by Employer

|

|

Number |

Percent of Total |

Percent In Closely Related Fields |

|

Local government |

54 |

9.5% |

79.6% |

|

State government |

60 |

10.6 |

85.0 |

|

Federal government |

78 |

13.8 |

77.9 |

|

Private industry/business |

227 |

40.0 |

44.9 |

|

Educational institution |

96 |

16.9 |

90.6 |

|

Nonprofit organization |

22 |

3.9 |

72.7 |

|

Consultant/self–employed |

30 |

5.3 |

73.3 |

|

Total |

567 |

100.0 |

67.4 |

|

Source: Recent graduates survey. |

|||

teacher. Many of our respondents saw themselves as performing geographic jobs even though this was not reflected in their job titles.

A third interpretation is that individuals working in fields other than those traditionally considered geographic find work in areas in which they have prior experience. Since our analysis neither holds constant the respondent's age nor classifies individuals on the basis of prior education or professional experience, we do not know the extent to which our survey is picking up prior preparation or work experience that leads to a nontraditional employment experience.

Greater confidence in our hypotheses about the recent labor market experiences of geographers requires more in-depth study of individual work experiences during the early- to mid-career years. Longitudinal analysis can verify the existence of a period of transition and adjustment when students move from part-time, temporary employment to full-time positions closely connected to their geographic training. Content analysis can decipher the potential relevance of the educational experience of students receiving degrees to tasks performed on the job. What if, for example, field-defined skills such as GIS, remote sensing, air photo interpretation, and cartography are not as important as the students' problem solving and decision making abilities? From a curricular standpoint, greater emphasis on professional practice, demeanor, and real world work experience may be more important than adding technical courses to academic curricula.

Convention Placement Service (CoPS)

A second glimpse at current labor market conditions in geography comes from the AAG's Convention Placement Service (CoPS). Held at the AAG's annual meeting, CoPS seeks to match job applicants with employers. Since 1989, the first year for which data are available, there has emerged a growing mismatch between the number of applicants and the number of interviews granted to these applicants (Fig. 1). In 1994, the 259 job seekers registered with CoPS attended only 156 interviews—an average of less than one interview per applicant.

Employers and job applicants who register with CoPS select from among a number of job

Table 5 Graduates (All Levels) by Employer and Occupation

|

Employer |

Cartographer (N=46) |

Environmental Manager/ Technician (N=73) |

GIS/Remote Sensing Specialist (N=59) |

Planner (N=38) |

Teacher (N=88) |

Other Geographic Professions (N=76) |

Other (N=184) |

|

Local government |

8.7% |

5.5% |

13.6% |

50.0% |

3.4% |

6.6% |

6.1% |

|

State government |

8.7 |

27.4 |

10.2 |

23.7 |

3.4 |

11.8 |

4.9 |

|

Federal government |

41.3 |

13.7 |

20.3 |

7.9 |

1.1 |

19.7 |

9.2 |

|

Private industry/ business |

26.1 |

42.5 |

44.1 |

15.8 |

1.1 |

32.9 |

67.4 |

|

Educational institution |

4.3 |

2.7 |

5.1 |

0 |

86.4 |

5.3 |

4.9 |

|

Nonprofit |

2.2 |

1.4 |

1.7 |

0 |

3.4 |

13.2 |

3.3 |

|

Consultant/self-employed |

8.7 |

6.8 |

5.1 |

2.6 |

1.3 |

10.5 |

4.3 |

|

Source: Recent graduates survey. |

|||||||

Figure 1:

Number of Applicants and Interviews Recorded by the AAG Convention Placement Service.

Note: The data point for interviews in 1993 is not available. The box containing 1993 interview records was lost in the mail between Atlanta and the AAG office in Washington.

categories. Many applicants and some employers list in more than one category. In 1994, 259 applicants accounted for some 556 listings, and 38 employers listed a total of 51 positions. Academic positions are included in two categories: an unfortunately large and heterogeneous physical/environmental/techniques group and a human/regional group. At the 1994 meeting, academic categories accounted for 43% of employment listings and one-third of the applicant listings (Table 6).

Applicants and employers for nonacademic jobs choose among four categories: physical/environmental (climatology, meteorology, geomorphology, hydrology, soils, biogeography, conservation, resources, ecology, environmental impact), planning (urban, transportation, land use, recreation, housing preservation, health, population), marketing/site selection/area studies (market research, real estate, public relations, advertising, regional expertise, travel consulting), and technical (cartography, remote sensing, photogrammetry, information systems, statistical and mathematical modeling). Applicants registered with CoPS were spread fairly evenly across the employment categories, but employers were concentrated in the nonacademic technical category—a sign of the strong link between GIS expertise and entry into the nonacademic labor market for geographers. There were a total of only six positions listed in the physical/environment, planning, and marketing/site selection/area studies classifications. While there were far more job applicants than positions even in the nonacademic technical category, the ratio of job seekers to positions was much lower than in the other nonacademic areas. For planning jobs, the ratio of applicants to jobs was more than 50 to 1!

Given the fact that these data apply only to individuals registered at the AAG annual meeting and employers attending this meeting, we make no claims that they are indicative of the

Table 6 Applicants and Employers Registered with the AAG's Career Opportunities and Placement Service in March 1994

|

|

Applicant Listings |

Employer Listings |

Ratio Applicants/Employers |

|

Academic |

|||

|

Physical/environmental/techniques |

85 (14.8%) |

14 (27.5%) |

6.1 |

|

Human/regional |

111 (19.3%) |

8 (15.7%) |

13.8 |

|

Nonacademic |

|||

|

Physical/environmental |

98 (17.7%) |

2 ( 3.9%) |

49.0 |

|

Planning |

107 (18.6%) |

2 ( 3.9%) |

53.5 |

|

Marketing/site selection/area studies |

71 (12.3%) |

2 ( 3.9%) |

35.5 |

|

Technical |

104 (18.1%) |

23 (45.1%) |

4.5 |

|

Source: Number of applicants and interviews recorded by the AAG Convention Placement Service. Physical/environmental: climatology, meteorology, geomorphology, hydrology, soils, biogeography, conservation, resources, ecology, environmental impact, etc. Planning: urban transportation, land use, recreation, housing, preservation, health, population, etc. Marketing/site selection/area studies: market research, real estate, public relations, advertising, regional expertise, travel consulting, etc. Technical: cartography, remote sensing, photogrammetry, information systems, statistical and mathematical modeling, etc. |

|||

total labor market for geographers. They do suggest a tighter labor market for new geographers at the master's and doctoral levels, and they signal the strong interest in techniques by potential employers of geographers.

Summary and Conclusions

The survey of recent graduates confirmed the continued importance of the five occupations in which geographers traditionally have been employed: cartographer, environmental manager/technician, GIS specialist, teacher, and urban/regional planner. These occupations accounted for slightly more than one-half of the respondents who reported their occupations. The strong association between "other" occupations and the private sector indicates that the private sector is the major destination of individuals who are not explicitly using their geographic training or are using it in occupations not traditionally associated with the field.

Results also revealed the quasi-professional position of geography relative to other social science fields. While only 16% of social science majors nationally were employed full-time in jobs closely related to their fields of study one year after graduation, this figure was 38% among the recent geography graduates in our survey. Geographers, although well placed by social science standards, fell below the norms of professional degree recipients, 48% of whom were employed in closely related fields.

Another finding involves the recent trend in the national labor market toward temporary, part-time employment as firms seek to reduce overhead costs and gain flexibility in managing the flow of work. Although our results need to be verified by careful longitudinal analysis, we picked up this trend in the experiences of recent geography graduates. Many newcomers to the labor market appear to face a period of transition between the time they receive their undergraduate degrees and the point at which they settle into stable, full-time employment. Geography programs can assist students in this transition period by encouraging or requiring internship experiences while in school, offering a senior seminar on the transition into the labor market, integrating more real-life experiences into the curriculum, and simply making students more aware of the challenges they will encounter in today's labor market.

Analysis of CoPS data suggested a tighter labor market for new geographers at the master's and doctoral levels and pointed to the strong link between GIS and other technical expertise and entry into the nonacademic labor market. Of the 29 nonacademic positions listed with CoPS in 1994, 23, or 79%, were in technical areas. Firms that participated in the 1994 national meetings appeared to be especially interested in graduate-level geographers with strong technical skills such as cartography, remote sensing, GIS, statistics, and mathematical modeling. Most geographers do not, however, learn these technical skills in an intellectual vacuum but in the context of the discipline's

systematic specialties. The third in this series of articles explores the specializations and skills that will be demanded of geography graduates in the near future.

Note

Literature Cited

National Center for Education Statistics. 1993. Digest of Education Statistics: 1993. NCES 993-292. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Employment Trends in Geography, Part 3: Future Demand Conditions

*Patricia Gober

Arizona State University

Amy K. Glasmeier

Pennsylvania State University

James M. Goodman

National Geographic Society

David A. Plane

University of Arizona

Howard A. Stafford

University of Cincinnati

Joseph S. Wood

George Mason University

The third and final article in this series about employment conditions in geography addresses the issue of future demand in both academic and nonacademic settings. To gain an understanding of future demand conditions in colleges and universities, we projected the retirement of AAG members by topical specialty and then matched these retirement trends with a profile of new faculty searches as reported by geography department chairs. We assessed the likely future demand for geography teachers at the precollegiate level through a survey of Geography Alliance Coordinators about teacher certification requirements and the education environments in their respective states. We speculated on how the kinds of jobs geographers do will be affected by changes now underway in the national and global economies. And finally, we conducted a small telephone survey of AAG corporate sponsors to determine how future business trends will affect the demand for geographers.

Academic Job Market

Retirements

The majority of new academic jobs in geography will involve replacements on existing lines rather than new lines. Of the 340 "likely" searches during the next five years reported by the departmental chairs who responded to our survey (See Part 1 in this series for a more complete discussion of this survey), 240 (72%) will involve replacement lines. Only 95 (28%) will entail new positions. Replacements occur when faculty members change jobs, leave the academy, retire, and die. In this section our goal is to focus on retirement—to estimate how many geographers will retire in the next five to ten years, to determine their likely specialties, and to access how the discipline will change as a result of their retirement.

One of the universal laws of demography, not to mention nature, is that every individual grows older one year at a time. This inexorable

process allows demographers to estimate with a high degree of accuracy how many people will be born, die, migrate, marry, and divorce each year. Processes that are sensitive to age, like retirement, can be accurately predicted by examining the size and characteristics of the cohort entering ages when retirement is likely. We applied this logic to AAG membership data and focused on geographers 50 years of age and older.

As of January 1, 1994, the cohort older than 50 years was predominantly male. Only 13% of this group was female compared with 27% of all AAG members and 33% of those under 50 years. Another perspective is afforded by examining AAG topical specialties by age of members. The AAG's 51 proficiency categories were collapsed to 25 groups. Members were permitted to indicate up to three topical proficiencies; some indicate three, some two, some one, and some did not record any specialty. We used only the first proficiency indicated by each member in our tabulations. If there is a systematic bias toward members first reporting their main topical specialty, then this counting procedure captures this bias. If there is no bias, this simplification provides an accurate sample of specialties of AAG members. Multiple counting of topical specializations would have overstated the number of persons in each category expected to retire.

The most popular specialties overall (with more than 200 members claiming them first) were cultural/historical, economic, cartography/photogrammetry, conservation/land use, GIS, applied/planning, climatology/meteorology, physical, urban, and geomorphology (Table 1). In comparing the number of individuals born before 1940 (those likely to retire in the next ten years) with those born after 1959 (likely to replace retiring members), the biggest discrepancy occurs in the GIS specialization. Only 18 individuals with a GIS specialization were born before 1940, while 182 geographers born after 1959 claim this as their first topical specialty. In addition, more younger than older geographers associate with cartography/photogrammetry, conservation/land use, and the more specialized subfields of physical geography such as biogeography, climatology, and geomorphology. More older than younger geographers claim specializations in cultural/historical geography, agricultural/rural geography, regional geography, geographic thought, and geographic education.

Table 1 AAG Membership by Year of Birth and Topical Specialty

|

|

Birth Year |

|||||

|

|

After 1959 |

1950–1959 |

1940–1949 |

Before 1940 |

Total |

After 1959– Before 1940 |

|

Agricultural/Rural |

26 |

48 |

37 |

45 |

156 |

–19 |

|

Applied/Planning |

64 |

75 |

101 |

62 |

302 |

2 |

|

Biogeography |

62 |

78 |

38 |

18 |

196 |

44 |

|

Cartography/Photogrammetry |

166 |

151 |

99 |

81 |

497 |

85 |

|

Remote Sensing |

40 |

45 |

24 |

18 |

127 |

22 |

|

Climatology |

82 |

93 |

61 |

45 |

281 |

37 |

|

Conservation/Land Use |

151 |

127 |

110 |

91 |

477 |

60 |

|

Cultural Ecology |

42 |

34 |

30 |

18 |

124 |

24 |

|

Cultural/Historical |

135 |

124 |

190 |

182 |

631 |

–47 |

|

Economic |

152 |

201 |

159 |

118 |

630 |

34 |

|

Geographic Education |

27 |

29 |

30 |

33 |

119 |

–6 |

|

GIS |

182 |

118 |

67 |

18 |

385 |

164 |

|

Geographic Thought |

2 |

6 |

1 |

14 |

23 |

–12 |

|

Geomorphology |

58 |

86 |

50 |

30 |

224 |

28 |

|

Physical |

66 |

72 |

75 |

54 |

267 |

12 |

|

Political |

40 |

42 |

38 |

36 |

156 |

4 |

|

Population |

17 |

30 |

39 |

23 |

109 |

–6 |

|

Quantitative |

8 |

8 |

15 |

6 |

37 |

2 |

|

Recreation/Tourism |

10 |

12 |

12 |

13 |

47 |

–3 |

|

Social |

34 |

35 |

20 |

12 |

101 |

22 |

|

Transportation/Communications |

14 |

16 |

22 |

11 |

63 |

3 |

|

Urban |

53 |

57 |

71 |

51 |

232 |

2 |

|

Water Resources |

19 |

30 |

14 |

14 |

77 |

5 |

|

Other |

20 |

18 |

37 |

39 |

114 |

–19 |

|

Regional |

6 |

10 |

11 |

17 |

44 |

–11 |

|

Source: 1993 AAG membership data. |

||||||

It is increasingly difficult to predict retirement rates for college and university faculty members or for any occupation because Congress, in amending the Age Discrimination in Employment Act in 1986, abolished the concept of a mandatory retirement age. Higher education was given special treatment in the sense that the act's protection did not apply to faculty over 70 years of age, but this provision was phased out in 1993 (Swan 1992). Today college and university faculty members have a great deal of latitude in the decision about when and under what conditions to retire. We used recent patterns of retirement in the AAG to predict the number of members who would retire in the near future. Retirement rates for 1993 AAG members were calculated by dividing the number of members reporting themselves as retired by the total number of members in each age class. These rates were then used to estimate the number of new retirees (a) during the period 1994-1998 and (b) for the period 1994-2003.

The percentages already retired were calculated using the 1993 data for the entire membership, by five- and ten-year age groups. The difference in retirement percentage between one age group and the next younger age group was multiplied by the number in the younger age group. This produces the number of new employment exits as each group progresses through the next five or ten years of their work careers. The 1993 retirement rates for the entire membership were applied to each of the subgroups. We assumed, therefore, that members of gender and specialty subgroups will retire at rates comparable to the AAG as a whole.

We estimate that 256 AAG members working at the start of 1994 will retire in the next five years and 617 in the next ten years. Most of the retirees will be male: 225 (88% of the total) in the next five years and 535 (87%) in the next ten years.

Not surprisingly, the cultural/historical category will account for more retirees than any other category (Table 2). Other specialties with many potential retirees are economic, conservation/land use, cartography/photogrammetry, applied/planning, physical, urban, climatology, and agricultural/rural.

New Faculty Hiring

Geography departments may or may not choose to replace retirees with individuals who have similar expertise. To gain an understanding of the expected future hiring practices of geography departments, we asked departmental chairs to indicate the specialty of new faculty hires. We used the same categories as

Table 2 Retirement Projections by Topical Specialty

|

|

Next 5 Years |

Next 10 Years |

|

Agricultural/Rural |

9 |

21 |

|

Applied/Planning |

14 |

32 |

|

Biogeography |

4 |

10 |

|

Cartography/Photogrammetry |

15 |

37 |

|

Remote Sensing |

3 |

10 |

|

Climatology |

8 |

22 |

|

Conservation/Land Use |

18 |

42 |

|

Cultural Ecology |

4 |

9 |

|

Cultural/Historical |

36 |

86 |

|

Economic |

24 |

58 |

|

Geographic Education |

8 |

18 |

|

GIS |

3 |

13 |

|

Geographic Thought |

3 |

6 |

|

Geomorphology |

6 |

16 |

|

Physical |

11 |

27 |

|

Political |

8 |

16 |

|

Population |

5 |

12 |

|

Quantitative |

2 |

4 |

|

Recreation/Tourism |

2 |

8 |

|

Social |

2 |

6 |

|

Transportation/Communications |

2 |

6 |

|

Urban |

8 |

23 |

|

Water Resources |

2 |

7 |

|

Other |

8 |

20 |

|

Regional |

3 |

6 |

|

Source: Projections based on 1993 AAG membership data. |

||

Table 3 Demand for Faculty Specialty Areas as Reported by Departmental Chairs and Specialties of Retiring AAG Members

|

Specialty |

Number of 5–Year Retirees (a) |

Percent of Total (b) |

Number of Likely Searches (c) |

Percent of Total (d) |

Ratio (d)/(b) |

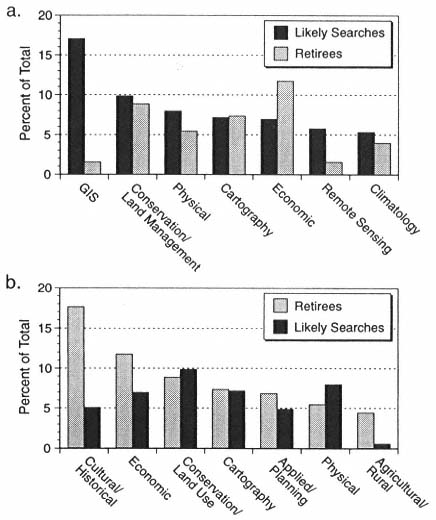

|