3—

Geography's Perspectives

Geography's relevance to science and society arises from a distinctive and integrating set of perspectives through which geographers view the world around them. This chapter conveys a sense of what is meant by a geographic perspective, whether it be applied in research, teaching, or practice. Due to space limitations, it does not attempt to cite the many excellent examples of research illustrating geography's perspectives; the citations refer mainly to broad-ranging summaries of geographic research that are intended as resources for further reading.

Taking time to understand geography's perspectives is important because geography can be difficult to place within the family of academic disciplines. Just as all phenomena exist in time and thus have a history, they also exist in space and have a geography. Geography and history are therefore central to understanding our world and have been identified as core subjects in American education. Clearly, this kind of focus tends to cut across the boundaries of other natural and social science disciplines. Consequently, geography is sometimes viewed by those unfamiliar with the discipline as a collection of disparate specialties with no central core or coherence.

What holds most disciplines together, however, is a distinctive and coherent set of perspectives through which the world is analyzed. Like other academic disciplines, geography has a well-developed set of perspectives:

- geography's way of looking at the world through the lenses of place, space, and scale;

- geography's domains of synthesis:1 environmental-societal dynamics relating human action to the physical environment, environmental dynamics linking physical systems, and human-societal dynamics linking economic, social, and political systems; and

- spatial representation using visual, verbal, mathematical, digital, and cognitive approaches.

-

These three perspectives can be represented as dimensions of a matrix of geographic inquiry as shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1

The matrix of geographic perspectives. Geography's ways of looking at the world—through its focus on place and scale (horizontal axis)—cuts across its three domains of synthesis: human-societal dynamics, environmental dynamics, and environmental-societal dynamics (vertical axis). Spatial representation, the third dimension of the matrix, underpins and sometimes drives research in other branches of geography.

Geography's Ways of Looking at the World

A central tenet of geography is that "location matters" for understanding a wide variety of processes and phenomena. Indeed, geography's focus on location provides a cross-cutting way of looking at processes and phenomena that other disciplines tend to treat in isolation. Geographers focus on "real world" relationships and dependencies among the phenomena and processes that give character to any location or place. Geographers also seek to understand relationships among places: for example, flows of peoples, goods, and ideas that reinforce differentiation or enhance similarities. Geographers study the "vertical" integration of characteristics that define place as well as the "horizontal'' connections between places. Geographers also focus on the importance of scale (in both space and time) in these relationships. The study of these relationships has enabled geographers to pay attention to complexities of places and processes that are frequently treated in the abstract by other disciplines.

Integration in Place

Places are natural laboratories for the study of complex relationships among processes and phenomena. Geography has a long tradition of attempting to understand how different processes and phenomena interact in regions and localities, including an understanding of how these interactions give places their distinctive character.

The systematic analysis of social, economic, political, and environmental processes operating in a place provides an integrated understanding of its distinctiveness or character. The pioneering work of Hägerstrand (1970), for example, showed how the daily activity patterns of people can be understood as the outcome of a process in which individuals are constrained by the availability and geographic accessibility of locations with which they can interact. Research in this tradition since has shown that the temporal and spatial sequences of actions of individuals follow typical patterns in particular types of environments and that many of the distinctive characteristics of places result from an intersection of behavioral sequences constrained by spatial accessibility to the opportunities for interaction. Such systematic analysis is particularly central to regional and human geography, and it is a theme to which much geographic research continually returns. When such systematic analysis is applied to many different places, an understanding of geographic variability emerges. Of course, a full analysis of geographic variability must take account of processes that cross the boundaries of places, linking them to one another, and also of scale.

Interdependencies Between Places

Geographers recognize that a "place" is defined not only by its internal characteristics but also by the flows of people, materials (e.g., manufactured

goods, pollutants), and ideas from other places. These flows introduce interdependencies between places that can either reinforce or reduce differences. For example, very different agricultural land-use practices have evolved under identical local environmental conditions as a result of the distance to market affecting the profitability of crops. At a macroscale, the widespread and global flow of Western cultural values and economic systems has served to reduce differences among many peoples of the world. An important focus of geography is on understanding these flows and how they affect place.

The challenge of analyzing the flows and their impacts on place is considerable. Such relationships have all the characteristics of complex nonlinear systems whose behavior is hard to represent or predict. These relationships are becoming increasingly important for science and decision making, as discussed in Chapters 5 and 6.

Interdependencies Among Scales

Geographers recognize that the scale of observation also matters for understanding geographic processes and phenomena at a place. Although geography is concerned with both spatial and temporal scales, the enduring dimension of the geographic perspective is the significance of spatial scales, from the global to the highly local.

Geographers have noted, for example, that changing the spatial scale of analysis can provide important insights into geographic processes and phenomena and into understanding how processes and phenomena at different scales are related. A long-standing concern of geographers has been the "regionalization problem," that is, the problem of demarcating contiguous regions with common geographic characteristics. Geographers recognize that the internal complexity and differentiation of geographic regions is scale-dependent and, thus, that a particular set of regions is always an incomplete and possibly misleading representation of geographic variation.

Identifying the scales at which particular phenomena exhibit maximum variation provides important clues about the geographic, as well as the temporal, scope of the controlling mechanisms. For example, spectral analyses of temperature data, revealing the geographic scales at which there is maximum similarity in temperature, can provide important clues about the relative influence of microclimates, air masses, and global circulation on temperature patterns. A global rise in average temperature could have highly differentiated local impacts and may even produce cooling in certain localities because of the way in which global, regional, and local processes interact. By the same token, national and international economic and political developments can have highly differentiated impacts on the economic competitiveness of cities and states. The focus on scale enables geographers to analyze the impact of global changes on local events—and the impact of local events on global changes.

Domains of Synthesis2

Geography's most radical departure from conventional disciplinary specializations can be seen in its fundamental concern for how humans use and modify the biological and physical environment (the biophysical environment) that sustains life, or environmental-societal dynamics. There are two other important domains of synthesis within geography as well: work examining interrelationships among different biophysical processes, or environmental dynamics, and work synthesizing economic, political, social, and cultural mechanisms, or human-societal dynamics. These domains cut across and draw from the concerns about place embedded in geography's way of looking at the world.

Environmental-Societal Dynamics

This branch of the discipline reflects, perhaps, geography's longest-standing concern and is thus heir to a rich intellectual tradition. The relationships that it studies—the dynamics relating society and its biophysical environment—today are not only a core element of geography but are also of increasingly urgent concern to other disciplines, decision makers, and the public. Although the work of geographers in this domain is too varied for easy classification, it includes three broad but overlapping fields of research: human use of and impacts on the environment, impacts on humankind of environmental change, and human perceptions of and responses to environmental change.

Human Use of and Impacts on the Environment

Human actions unavoidably modify or transform nature; in fact, they are often intended specifically to do so. These impacts of human action have been so extensive and profound that it is now difficult to speak of a "natural" environment. Geographers have contributed to at least three major global inventories of human impacts on the environment (Thomas, 1956; Turner et al., 1990; Mather and Sdasyuk, 1991) and have contributed to the literature of assessment, prescription, and argument regarding their significance. Studies at local and regional levels have clarified specific instances of human-induced landscape transformation: for example, environmental degradation in the Himalayas, patterns and processes of deforestation in the Philippines and the Amazon, desiccation of the Aral Sea, degradation of landscapes in China, and the magnitude and character of pre-Hispanic environmental change in the Americas.

Geographers study the ways in which society exploits and, in doing so,

|

2 |

Citations in this section do not refer to major research contributions since these are the focus of Chapter 5. They refer the reader to books and articles that provide a more detailed discussion of the topic than can be provided here. |

degrades, maintains, improves, or redefines its natural resource base. Geographers ask why individuals and groups manipulate the environment and natural resources in the ways they do (Grossman, 1984; Hecht and Cockburn, 1989). They have examined arguments about the roles of carrying capacity and population pressures in environmental degradation, and they have paid close attention to the ways in which different cultures perceive and use their environments (Butzer, 1992). They have devoted considerable attention to the role of political-economic institutions, structures, and inequities in environmental use and alteration, while taking care to resist portraying the environment as an empty stage on which social conflicts are acted out (Grossman, 1984; Zimmerer, 1991; Carney, 1993).

Environmental Impacts on Humankind

Consequences for humankind of change in the biophysical environment—whether endogenous or human-induced—are also a traditional concern for geographers. For instance, geographers were instrumental in extending the approaches of environmental impact analysis to climate. They have produced important studies of the impact of natural climate variation and projected human-induced global warming on vulnerable regions, global food supply, and hunger. They have studied the impacts of a variety of other natural and environmental phenomena, from floods and droughts to disease and nuclear radiation releases (Watts, 1983; Kates et al., 1985; Parry et al., 1988; Mortimore, 1989; Cutter, 1993). These works have generally focused on the differing vulnerabilities of individuals, groups, and geographic areas, demonstrating that environmental change alone is insufficient to understand human impacts. Rather, these impacts are articulated through societal structures that give meaning and value to change and determine in large part the responses taken.

Human Perceptions of and Responses to Environmental Change

Geographers have long-recognized that human-environment relations are greatly influenced not just by particular activities or technologies but also by the very ideas and attitudes that different societies hold about the environment. Some of geography's most influential contributions have documented the roots and character of particular environmental views (Glacken, 1967; Tuan, 1974). Geographers have also recognized that the impacts of environmental change on human populations can be strongly mitigated or even prevented by human action. Accurate perception of change and its consequences is a key component in successful mitigation strategies. Geographers studying hazards have made important contributions to understanding how perceptions of risk vary from reality (Tuan, 1974) and how communication of risk can amplify or dampen risk signals (Palm, 1990; Kasperson and Stallen, 1991).

Accurate perceptions of available mitigation strategies is an important aspect

of this domain, captured by Gilbert F. White's geographic concept of the "range of choice," which has been applied to inform policy by illuminating the options available to different actors at different levels (Reuss, 1993). In the case of floodplain occupancy, for instance, such options include building flood control works, controlling development in flood-prone areas, and allowing affected individuals to absorb the costs of disaster. In the case of global climate change, options range from curtailing greenhouse gas (e.g., carbon dioxide) emissions to pursuing business as usual and adapting to change if and when it occurs. Geographers have assembled case studies of societal responses to a wide variety of environmental challenges as analogs for those posed by climate and other environmental change and have examined the ways in which various societies and communities interpret the environments in questions (Jackson, 1984; Demeritt, 1994; Earle, 1996).

Environmental Dynamics

Geographers often approach the study of environmental dynamics from the vantage point of natural science (Mather and Sdasyuk, 1991). Society and its roles in the environment remain a major theme, but human activity is analyzed as one of many interrelated mechanisms of environmental variability or change. Efforts to understand the feedbacks among environmental processes, including human activities, also are central to the geographic study of environmental dynamics (Terjung, 1982). As in the other natural sciences, advancing theory remains an overarching theme, and empirical verification continues to be a major criterion on which efficacy is judged.

Physical geography has evolved into a number of overlapping subfields, although the three major subdivisions are biogeography, climatology, and geomorphology (Gaile and Willmott, 1989). Those who identify more with one subfield than with the others, however, typically use the findings and perspectives from the others to inform their research and teaching. This can be attributed to physical geographers' integrative and cross-cutting traditions of investigation, as well as to their shared natural science perspective (Mather and Sdasyuk, 1991). Boundaries between the subfields, in turn, are somewhat blurred. Biogeographers, for example, often consider the spatial dynamics3 of climate, soils, and topography when they investigate the changing distributions of plants and animals, whereas climatologists frequently take into account the influences that landscape heterogeneity and change exert on climate. Geomorphologists also account for climatic forcing and vegetation dynamics on erosional and depositional process. The three major

subfields of physical geography, in other words, not only share a natural science perspective but differ simply with respect to emphasis. Each subfield, however, will be summarized separately here in deference to tradition.

Biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distributions of organisms at various spatial and temporal scales, as well as the processes that produce these distribution patterns. Biogeography lies at the intersection of several different fields and is practiced by both geographers and biologists. In American and British geography departments, biogeography is closely allied with ecology.

Geographers specializing in biogeography investigate spatial patterns and dynamics of individual plant and animal taxa and the communities and ecosystems in which they occur, in relation to both natural and anthropogenic processes. This research is carried out at local to regional spatial scales. It focuses on the spatial characteristics of taxa or communities as revealed by fieldwork and/or the analysis of remotely sensed images. This research also focuses on historic changes in the spatial characteristics of taxa or communities as reconstructed, for example, from land survey records, photographs, age structures of populations, and other archival or field evidence. Biogeographers also reconstruct prehistoric and prehuman plant and animal communities using paleoecological techniques such as pollen analysis of lake sediments or faunal analysis of midden or cave deposits. This research has made important contributions to understanding the spatial and temporal dynamics of biotic communities as influenced by historic and prehistoric human activity as well as by natural variability and change.

Climatology

Geographic climatologists are interested primarily in describing and explaining the spatial and temporal variability of the heat and moisture states of the Earth's surface, especially its land surfaces. Their approaches are quite varied, including (1) numerical modeling of energy and mass fluxes from the land surface to the atmosphere; (2) in situ measurements of mass and energy fluxes, especially in human-modified environments; (3) description and evaluation of climatically relevant characteristics of the land surface, often through the use of satellite observations; and (4) the statistical decomposition and categorization of weather data. Geographic climatologists have made numerous contributions to our understanding of urban and regional climatic systems, and they are beginning to examine macroscale climatic change as well. They have also examined the statistical relationships among weather, climate, and sociological data. Such analyses have suggested some intriguing associations, for example, between urban growth and warming (Oke, 1979) and the seasonal heating cycle and crime frequency (Harries et al., 1984).

Geomorphology

Geomorphological research in geography emphasizes the analysis and prediction of Earth surface processes and forms. The Earth's surface is constantly being altered under the combined influences of human and natural factors. The work of moving ice, blowing wind, breaking waves, collapse and movement from the force of gravity, and especially flowing water sculptures a surface that is constantly being renewed through volcanic and tectonic activity.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, geomorphological research has focused on examining stability in the landscape and the equilibrium between the forces of erosion and construction. In the past two decades, however, emphasis has shifted toward efforts to characterize change and the dynamic behavior of surface systems. Whatever the emphasis, the method of analysis invariably involves the definition of flows of mass and energy through the surface system, and an evaluation or measurement of forces and resistance at work. This analysis is significant because if geomorphologists are to predict short-term, rapid changes (such as landslides, floods, or coastal erosion in storms) or long-term, rapid changes (such as erosion caused by land management or strip mining), the natural rates of change must first be understood.

Human-Societal Dynamics: From Location Theory to Social Theory

The third domain focuses on the geographic study of interrelated economic, social, political, and cultural processes. Geographers have sought a synthetic understanding of such processes through attention to two types of questions: (1) the ways in which those processes affect the evolution of particular places and (2) the influence of spatial arrangements and our understanding on those processes. Much of the early geographical work in this area emphasized locational decision making; spatial patterns and their evolution were explained largely in terms of the rational spatial choices of individual actors (e.g., Haggett et al., 1979; Berry and Parr, 1988).

Beginning with Harvey (1973), a new cohort of scholars began raising questions about the ways in which social structures condition individual behavior and, more recently, about the importance of political and cultural factors in social change (Jackson and Penrose, 1993). This has matured as an influential body of work founded in social theory, which has devoted considerable effort to understanding how space and place mediate the interrelations between individual actions and evolving economic, political, social, and cultural patterns and arrangements and how spatial configurations are themselves constructed through such processes (e.g., Gregory and Urry, 1985; Harvey, 1989; Soja, 1989; Wolch and Dear, 1989).

This research has gained wide recognition both inside and outside the disci-

pline of geography; as a result, issues of space and place are now increasingly seen as central to social research. Indeed, one of the principal journals for interdisciplinary research in social theory, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, was founded by geographers. The nature and impact of research that has sought to bridge the gap between social theory and conceptualizations of space and place are evident in recent studies of both the evolution of places and the interconnections among places.

Societal Synthesis in Place

Geographers who study societal processes in place have tended to focus on micro- or mesoscales. Research on cities has been a particularly influential area of research, showing how the internal spatial structure of urban areas depends on the operation of land markets, industrial and residential location decisions, population composition, forms of urban governance, cultural norms, and the various influences of social groups differentiated along lines of race, class, and gender. The impoverishment of central cities has been traced to economic, social, political, and cultural forces accelerating suburbanization and intraurban social polarization. Studies of urban and rural landscapes examine how the material environment reflects, and shapes, cultural and social developments, in work ranging from interpretations of the social meanings embedded in urban architecture to analyses of the impacts of highway systems on land uses and neighborhoods (Knox, 1994).

Researchers have also focused on the living conditions and economic prospects of different social and ethnic groups in particular cities, towns, and neighborhoods, with particular attention recently to how patterns of discrimination and employment access have influenced the activity patterns and residential choices of urban women (e.g., McDowell, 1993a, b). Researchers have also attempted to understand the economic, social, and political forces reinforcing the segregation of poor communities, as well as the persistence of segregation between certain racial and ethnic groups, irrespective of their socioeconomic status. A geographical perspective on such issues ensures that groups are not treated as undifferentiated wholes. By focusing attention on disadvantaged communities in inner cities, for example, geographers have offered significant evidence of what happens when jobs and wealthier members of a community leave to take advantage of better opportunities elsewhere (Urban Geography, 1991).

Geographical work on place is not limited to studies of contemporary phenomena. Geographers long have been concerned with the evolving character of places and regions, and geographers concerned with historical developments and processes have made important contributions to our understanding of places past and present. These contributions range from sweeping interpretations of the historical evolution of major regions (e.g., Meinig, 1986 et seq.) to analyses of the changing ethnic character of cities (Ward, 1971) to the role of capitalism in

urban change (Harvey, 1985a, b). Studies along these lines go beyond traditional historical analysis to show how the geographical situation and character of places influence not only how those places develop but larger social and ideological formations as well.

Space, Scale, and Human-Societal Dynamics

Studies of the social consequences of linkages between places focus on a variety of scales. One body of research addresses spatial cognition and individual decision making and the impact of individual action on aggregate patterns. Geographers who study migration and residential choice behavior seek to account for the individual actions underlying the changing social structure of cities or shifting interurban populations. Research along these lines has provided a framework for modeling the geographical structure of interaction among places, resulting inter alia in the development of operational models of movement and settlement that are now widely used by urban and regional planners throughout Europe (Golledge and Timmermans, 1988).

Geographers also have contributed to the refinement of location theories that reflect actual private and public decision making. Initially, much of this research looked at locational issues at particular moments in time. Work by Morrill (1981) on political redistricting, for example, provided insights into the many ways in which administrative boundary drawing reflects and shapes political ideas and practices. More recent work has focused on the evolution of industrial complexes and settlement systems. This work has combined the insights of location theory with studies of individual and institutional behavior in space (Macmillan, 1989). At the interurban and regional scales, geographers have studied nationwide shifts in the location and agglomeration of industries and interurban migration patterns. These studies have revealed important factors shaping the growth prospects of cities and regions.

An interest in the relationship between individual behavior and broader-scale societal structures prompted geographers to consider how individual decisions are influenced by, and affect, societal structures and institutions (e.g., Peet and Thrift, 1989). Studies have tackled issues ranging from human reproduction and migration decisions to recreation and political protest. Researchers have shown how movement decisions depend on social and political barriers, the distribution of economic and political resources and broader-scale processes of societal restructuring. They have examined how the increased mobility of jobs and investment opportunities have affected local development strategies and the distribution of public resources between firms and households.

Indeed, there is new interest in theorizing the geographical scales at which different processes are constituted and the relationship between societal processes operating at different scales (Smith, 1992; Leitner and Delaney, 1996). Geographers recognize that social differences from place to place reflect not only differ-

ences in the characteristics of individual localities but also differences in how they are affected by societal processes operating at larger scales. Research has shown, for example, that the changing growth prospects of American cities and regions cannot adequately be understood without taking into account the changing position of the United States in the global system and the impact of this change on national political and economic trends (Peet, 1987; Smith and Feagin, 1987).

Geographic research also has focused explicitly on the spatial manifestations of institutional behavior, notably that of large multilocational firms; national, state, and local governments; and labor unions. Research on multilocational firms has examined their spatial organization, their use of geographical strategies of branch-plant location and marketing in order to expand into or maintain geographically defined markets, and the way their actions affect the development possibilities of different places (Scott, 1988b; Dicken, 1992). Research into state institutions has focused on such issues as territorial integration and fragmentation; evolving differences in the responsibilities and powers exercised by state institutions at different geographical scales; and political and economic rivalries between territories, including their impact on political boundaries and on geopolitical spheres of influence. Observed shifts in the location of political influence and responsibility away from traditional national territories to both local states and supranational institutions demonstrate the importance of studying political institutions across a range of geographical scales (Taylor, 1993).

Spatial Representation

The importance of spatial representation as a third dimension of geography's perspectives (see Figure 3.1) is perhaps best exemplified by the long and close association of cartography with geography (see Chapter 4). Research emphasizing spatial representation complements, underpins, and sometimes drives research in other branches of geography and follows directly from the thesis that location matters. Geographers involved in spatial representation research use concepts and methods from many other disciplines and interact with colleagues in those fields, including computer science, statistics, mathematics, geodesy, civil engineering, cognitive science, formal logic, cognitive psychology, semiotics, and linguistics. The goals of this research are to produce a unified approach to spatial representation and to devise practical tools for representing the complexities of the world and for facilitating the synthesis of diverse kinds of information and diverse perspectives.

How geographers represent geographic space, what spatial information is represented, and what space means in an age of advanced computer and telecommunications technology are critical to geography and to society. Research linking cartographic theory with philosophies of science and social theory has demonstrated that the way problems are framed, and the tools that are used to structure and manipulate data, can facilitate investigation of particular categories of prob-

lems and, at the same time, prevent other categories of problems from even being recognized as such. By dictating what matters, representations help shape what scientists think and how they interpret their data (Sack, 1986; Harley, 1988; Wood, 1992).

Geographic approaches to spatial representation are closely linked to a set of core spatial concepts (including location, region, distribution, spatial interaction, scale, and change) that implicity constrain and shape how geographers represent what they observe. In effect, these concepts become a priori assumptions underlying geographic perspectives and shaping decisions by geographers about how to represent their data and what they choose to represent.

Geographers approach spatial representation in a number of ways to study space and place at a variety of scales. Tangible representations of geographic space may be visual, verbal, mathematical, digital, cognitive, or some combination of these. Reliance on representation is of particular importance when geographic research addresses intangible phenomena (e.g., atmospheric temperature or average income) at scales beyond the experiential (national to global) and for times in the past or future. Tangible representations (and links among them) also provide a framework within which synthesis can take place. Geographers also study cognitive spatial representations—for example, mental models of geographic environments—in an effort to understand how knowledge of the environment influences peoples' behavior in that environment and make use of this knowledge of cognitive representation in developing approaches to other forms of representation.

Visual representation of geographic space through maps was a cornerstone of geographic inquiry long before its formal recognition as an academic area of research, yet conventional maps are not the only visual form used in geographic research. Figure 3.2 shows that conventional maps occupy a midpoint along a continuum of visual representation forms. This continuum can be defined by a dimension scale, which ranges from atomic to cosmological, and abstractness level, which ranges from images to line drawings.

Due to the centrality of geographic maps as a means for spatial representation, however, concepts developed for mapping have had an impact on all forms of spatial representation. This role as a model and catalyst for visual representation throughout the sciences is clear in Hall's (1992) recent popular account of mapping as a research tool used throughout science, as well as the recognition by computer scientists that maps are a fundamental source of many concepts used in scientific visualization (Collins, 1993).

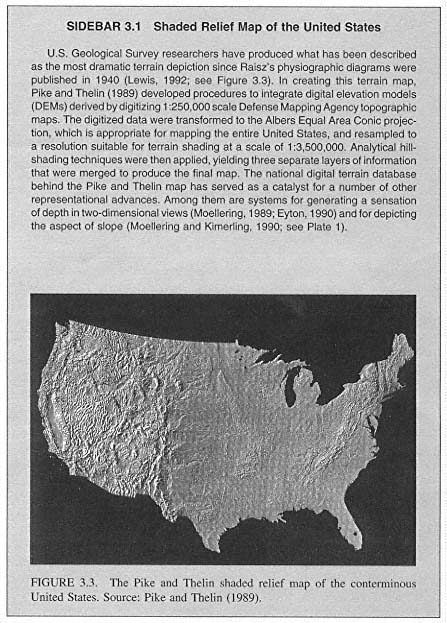

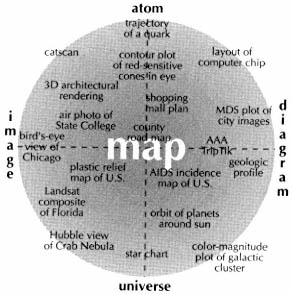

An active field of geographic research on spatial representation involves formalizing the ''language" for visual geographic representation. Another important field of research involves improved depiction of the Earth's surface. A notable example is the recent advance in matching computational techniques for terrain shading with digital elevation databases covering the conterminous United States (see Sidebar 3.1).

Figure 3.2

The conventional map is one of many visual representations of space used by geographers and other scientists. As one of a continuum of spatial representations, maps occupy a "fuzzy" category defined by an "abstractness level" (horizontal axis) and a "scale dimension" (vertical axis).

Source: After MacEachren (1995, Figure 4.3).

Verbal representation refers to attempts to evoke landscapes through a carefully constructed description in words. Some of the geographers who have become best known outside the discipline rely almost exclusively on this form of representation. Geographers have drawn new attention to the power of both verbal and visual representations, exploring the premise that every representation has multiple, potentially hidden, and perhaps duplicitous, meanings (Gregory, 1994).

A current field of research linking verbal and visual forms of spatial representation concerns hypermedia documents designed for both research and instructional applications. The concept of a geographic script (analogous to a movie script) has been proposed as a strategy for leading people through a complex web of maps, graphics, pictures, and descriptions developed to provide information about a particular issue (Monmonier, 1992).

Mathematical representations include models of space, which emphasize location, regions, and distributions; models of functional association; and models of process, which emphasize spatial interaction and change in place. Visual maps, of course, are grounded in mathematical models of space, and it can be demonstrated that all map depictions of geographic position are, in essence, mathematical transformations from the Earth to the plane surface of the page or

computer display screen. The combination of visual and mathematical representation draws on advantages inherent in each (see Plate 2).

A good example of the link between mathematical and visual representation is provided by the Global Demography Project (Tobler et al., 1995). In this project more than 19,000 digitized administrative polygons and associated population counts covering the entire world were extrapolated to 1994 and then converted to spherical cells. The data are available as a raster map, accessible on the World Wide Web from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Consortium for the International Earth Science Information Network, Socioeconomic and Economic Data Center, which supported the project.

Cognitive representation is the way individuals mentally represent information about their environment. Human cognitive representations of space have been studied in geography for more than 25 years. They range from attempts to derive "mental maps" of residential desirability to assessing ways in which knowledge of spatial position is mentally organized, the mechanisms through which this knowledge expands with behavior in environments, and the ways in which environmental knowledge can be used to support behavior in space. The resulting wealth of knowledge about spatial cognition is now being linked with visual and digital forms of spatial representation. This link is critical in such research fields as designing interfaces for geographic information systems (GISs) and developing structures for digital geographic databases. Recent efforts to apply the approaches of cognitive science to modeling human spatial decision making have opened promising research avenues related to way finding, spatial choice, and the development of GIS-based spatial decision support systems. In addition, research about how children at various stages of cognitive development cope with maps and other forms of spatial representation is a key component in efforts to improve geography education.

Digital representation is perhaps the most active and influential focus of representational research because of the widespread use of GISs and computer mapping. Geographers have played a central role in the development of the representational schemes underpinning GISs and computer mapping systems. Geographers working with mathematicians at the U.S. Census Bureau in the 1960s were among the first to recognize the benefits of topological structures for vector-based digital representations of spatial data. This vector-based approach (the Dual Independent Map Encoding system, more recently replaced by the Topologically Integrated Geographical Encoding and Referencing system, or TIGER) has become the linchpin of the Census Bureau's address-matching system. It has been adapted to computer mapping through an innovative system for linking topological and metrical geographic representations. Related work by geographers and other scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey's (USGS) National Mapping Division led to the development of a digital mapping system (the Digital Line Graph format) and has allowed the USGS to become a major provider of digital spatial data.

Geographers working in GIS research have investigated new approaches to raster (grid-based) data structures. Raster structures are compatible with the structure of data in remote sensing images, which continue to be a significant source of input data for GIS and other geographic applications. Raster structures are also useful for overlying spatial data. Developments in vector and raster data structures have been linked through an integrated conceptual model that, in effect, is eliminating the raster-vector dichotomy (Peuquet, 1988).

U.S. geographers have also played a leading role in international collaboration directed at the generalization of digital representations (Buttenfield and McMaster, 1991). This research is particularly important because solutions to key generalization problems are required before the rapidly increasing array of digital georeferenced data can be integrated (through GISs) to support multiscale geographic analysis. Generalization in the digital realm has proved to be a difficult problem because different scales of analysis demand not only more or less detailed information but also different kinds of information represented in fundamentally different ways.

Increasingly, the aspects of spatial representation discussed above are being linked through digital representations. Transformations from one representation to another (e.g., from mathematical to visual) are now routinely done using a digital representation as the intermediate step. This reliance on digital representation as a framework for other forms of representation brings with it new questions concerning the impact of digital representation on the construction of geographic knowledge.

One recent outgrowth of the spatial representation traditions of geography is a multidisciplinary effort in geographic information science. This field emphasizes coordination and collaboration among the many disciplines for which geographic information and the rapidly emerging technologies associated with it are of central importance. The University Consortium for Geographic Information Science (UCGIS), a nonprofit organization of universities and other research institutions, was formed to facilitate this interdisciplinary effort. UCGIS is dedicated to advancing the understanding of geographic processes and spatial relationships through improved theory, methods, technology, and data.

Geographic Epistemologies4

This survey of geography's perspectives illustrates the variety of topics pursued by geography as a scientific discipline, broadly construed. The methods and approaches that geographers have used to generate knowledge and understanding of the world about them—that is, its epistemologies—are similarly broad. The post-World War II surge in theoretical and conceptual geography, work

that helped the discipline take its place alongside other social, environmental, and natural sciences at that time, was triggered by adoption of what has been termed a "positivist" epistemology during the quantitative revolution of the 1960s (Harvey, 1969). Extensive use is still made of this approach, especially in studying environmental dynamics but also in spatial analysis and representation. It is now recognized, however, that the practice of such research frequently diverges from the ideals of positivism. Many of these ideals—particularly those of value neutrality and of the objectivity of validating theories by hypothesis testing—are in fact unattainable (Cloke et al., 1991; Taaffe, 1993).

Recognition of such limitations has opened up an intense debate among geographers about the relative merits of a range of epistemologies that continue to enliven the field (Gregory, 1994). Of particular interest, at various points in this debate, have been the following:

- Approaches stressing the role of political and economic structures in constraining the actions of human agents, drawing on structural, Marxist, and structurationist traditions of thought that emphasize the influence of frequently unobservable structures and mechanisms on individual actions and thereby on societal and human-environmental dynamics—carrying the implication that empirical tests cannot determine the validity of a theory (Harvey, 1982).

- Realist approaches, which recognize the importance of higher-level conceptual structures but insist that theories be able to account for the very different observed outcomes that a process may engender in different places (Sayer, 1993).

- Interpretive approaches, a traditional concern of cultural geography, which recognize that similar events can be given very different but equally valid interpretations, that these differences stem from the varying societal and geographical experiences and perspectives of analysts, and that it is necessary to take account of the values of the investigator rather than attempting to establish his or her objectivity (Buttimer, 1974; Tuan, 1976; Jackson, 1989).

- Feminist approaches, which argue that much mainstream geography fails to acknowledge both a white masculine bias to its questions and perspectives and also a marginalization of womens' lives in its analysis (McDowell, 1993b; Rose, 1993).

- Postmodernist or "countermodernist" approaches, which argue that all geographic phenomena are social constructions, that understandings of these are a consequence of societal values and norms and the particular experiences of individual investigators, and that any grand theory is suspect because it fails to recognize the contingent nature of all interpretation. It is argued that this has resulted in a "crisis of representation," that is, a situation in which the relative "accuracy" of any representation of the world becomes difficult to adjudicate (Keith and Pile, 1993). Feminist and postmodern scholars argue that it is necessary to incorporate a diverse group of subjects, researchers, and ways of knowing if the subject matter of geography is to embrace humankind.

Geographers debate the philosophical foundations of their research in ways similar to debates among other natural scientists, social scientists, and humanists, although with a particular emphasis on geographical views of the world and on representation. These debates have not been restricted to the philosophical realm but have had very practical consequences for substantive research, often resulting in contrasting theoretical interpretations of the same phenomenon. For example, neopositivist and structural accounts of the development of settlement systems have evolved through active engagement with one another, and debates about how to assess the environmental consequences of human action have ranged from quantitative cost-benefit calculations to attempts to compare and contrast instrumental with local and indigenous interpretations of the meaning and significance of nature. In subsequent chapters we have not attempted to mark these different perspectives, choosing instead to stress the phenomena studied rather than the approaches taken. We attempt selectively to include leading researchers from different perspectives working on a particular topic, to the extent that their work can be constituted as scientific in the broad sense that we use that term (see Sidebar 1.1).

While we recognize that different perspectives frequently lead to intense debates engaging very different views of the same phenomenon, there is no space in this report to detail these debates. Such often vigorous interchanges and differences strengthen geography as both a subject and a discipline, however, reminding researchers that different approaches may be relevant for different kinds of questions and that the selection of any approach shapes both the kind of research questions asked and the form the answers take, as well as the answers themselves.