3

Introduction to the Concepts and Issues Underlying Underconsumption of Field Rations

Herbert L. Meiselman1

Not Eating Enough, 1995

Pp. 57–64. Washington, D.C.

National Academy Press

INTRODUCTION

The overall purpose of the workshop from which this book was developed was for the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine (USARIEM) and the U.S. Army Natick Research, Development and Engineering Center (NRDEC) to ask the Committee on Military Nutrition Research for assistance in developing and assessing a strategy. Researchers at USARIEM and NRDEC have identified a problem: underconsumption of military rations. They recognized that this problem is important to the military and to the general research community, which is interested in why people eat and why they do not eat. Researchers at NRDEC have identified possible solutions to the problem. It is now time to review the problem and the proposed solutions to ensure full consideration of the approach, the data, and other alternatives.

It has been difficult to gain a perspective on recent research because so much of the research on human eating focuses on the individual and the food. This report also treats the individual and the food, but will add an important third dimension, the eating situation or context. These three factors together are necessary to understand why soldiers eat or do not eat, and they must be considered and addressed to improve the current situation. Below is a brief outline of how the meeting and the book were conceived and developed to fully cover these three topics and other important issues.

Interest in what goes on in the field regarding Army personnel and rations and whether there is a problem of underconsumption began in 1983 with the first extended, comparative test of a field ration. NRDEC conducted a 34-d test, with one group receiving 3 Meals, Ready-to-Eat (MREs)/d providing 3,600 kcal and a control group receiving 2 fresh meals and 1 MRE/d providing the same number of calories. The MRE group ate an average of 2,189 kcal over the 34 days, but their caloric intake continuously declined over that period, ending at 1,681 kcal. Soldiers lost an average of 8.11 lbs (3.7 kg) (4.7 percent body weight), with some individuals losing up to 11 percent body weight. The soldiers rated their food 7.05 on a standard 9-point hedonic rating scale (Hirsch et al., 1985).

At about the same time, a study was conducted with a comparison group of young males (university students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology [MIT]) consuming MREs. Participants received either 3 MREs/d or freshly prepared food for 45 days. Of course, the students did not receive their food out-of-doors as the soldiers did. The students had tables and chairs, set mealtimes, tableware and dishes, and the ability to heat food. The MIT students averaged a daily caloric intake of 3,149 kcal over the 45 days. Their caloric intake also declined over the 45 days. They lost a little weight (average, 1.5 lbs [0.7 kg] or 1 percent body weight). They rated the food 6.05 on the standard 9-point hedonic rating scale (Hirsch and Kramer, 1993; Kramer et al., 1992).

It was not clear during initial comparisons of the soldier study and the student study what was responsible for the 1,000 kcal difference in intake and the 1.0 difference in acceptance ratings. Soldiers rated their food higher but ate less; students rated their food lower but ate more. During analysis, the food and the individual were considered first; then it became apparent that the eating situation should be examined.

The analysis had begun to develop further when a paper for the 1987 meeting on food acceptability was published, stating that "field studies have led us to conclude that important factors controlling consumption of food in natural eating situations are the situational variables which make it more or less convenient for us to eat and which signal meal times" (Meiselman et al., 1988, p. 77).

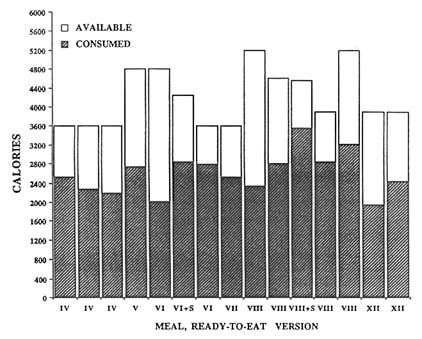

Today, there is a data base of 15 studies conducted by USARIEM and NRDEC. These studies show an unchanging pattern of ration consumption and ration waste in which these two factors appear to account for two-thirds and one-third of what is provided, respectively (Figure 3-1). What has also begun to emerge is that eating in the field and eating in dining rooms produce different food intakes and different patterns of food acceptance (see Baker-Fulco, Chapter 8 in this volume) (Table 3-1).

The chapters that follow provide baseline information on what happens in U.S. Army field feeding. During the workshop, Peter Motrynczuk of the U.S. Army Quartermaster Center and School discusses the present and planned future concepts for how to feed the Army in the field. A summary of his presentation is included as Chapter 4. Celia F. Adolphi of the Department of the Army presents the views of commanders on troop feeding and nutrition obtained at the Army War College in Chapter 5.

The next two chapters cover what should be consumed and what is provided. David D. Schnakenberg reviews the history of nutritional criteria for feeding the Army and specifically details the current nutritional criteria for

FIGURE 3-1 Average calories available and consumed in Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE) field tests.

TABLE 3-1 Consumption and Acceptance of Army Packaged Field Rations

|

Field |

Garrison |

||

|

(kcal) |

Hedonic Rating |

(kcal) |

Hedonic Rating |

|

2.189 |

7.05 |

3,149 |

6.50 |

|

2.876 |

6.90 |

3,848 |

6.30 |

rations in Chapter 6. Gerald A. Darsch, who heads the Sustainability Directorate at NRDEC, and Philip Brandler cover the history of MRE development and plans for future ration development in Chapter 7.

Finally, the statement of the current situation is completed with two chapters on what soldiers eat in the field. Carol J. Baker-Fulco, USARIEM, summarizes a number of ration studies in a variety of environments (see Chapter 8 in this volume), and Edward Hirsch, NRDEC, summarizes studies of ration changes in the field (see Chapter 9 in this volume). Hirsch's review of ration acceptance and consumption parallels Darsch's review of the history of ration development.

Part III considers the food. Armand V. Cardello, a psychologists at NRDEC, presents research findings on product image, emphasizing the role of consumer expectations in Chapter 10. This research raises the important question of whether one should consider expected acceptance rather than the traditional measures of actual acceptance. Barbara Rolls of The Pennsylvania State University reviews her research on sensory-specific satiety and its implications for meal variety and dietary variety (see Chapter 11 in this volume). This and related research have led to the conclusion that food variety is a complex phenomenon; simply adding more choices does not necessarily add more variety. Rolls also focuses on the issue of portion sizes and snacks.

Dianne Engell, a psychologist at NRDEC, examines the important role of water intake in ration consumption in Chapter 12. Engell makes the important points that most water is consumed at mealtimes (i.e., with foods), many calories are consumed as liquids, and people without adequate water eat less food. All of these illustrate the critical role of liquids and hydration. The problem of underconsumption of rations cannot be understood or solved without considering liquids.

Eileen G. Thompson, former Marketing Research Director of Quaker Oats, provides an industry perspective on food issues in Chapter 13. Some of her points reinforce material presented elsewhere in this volume (e.g., liking is not a univariate problem; visual appeal and naming are critical), while other points are uniquely her own (e.g., critical role of complex seasoning; how testing methodology affects seasoning choice).

The current state of research on how food and food acceptability affect food selection and intake is indicated by the chapters in Part III. These data clearly indicate that the field is not ready to entirely refocus on nonfood factors to understand why people eat. There is a great deal more to learn about the important issues of food variety, food portions, food seasoning, and food presentation.

The next three chapters that comprise Part IV provide state-of-the-art answers to the question, "So what?" Given that soldiers underconsume, what are the implications for their physical and cognitive performance and for their overall medical well-being? Karl E. Friedl, from the Army Operational Medicine Research Program at the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command and formerly from USARIEM, surveys the data to date in a series of rugged field tests (see Chapter 14 in this volume). Friedl identifies what might work as a performance indicator (lift capacity), what is less likely to work as an indicator (handgrip strength), and what level of underconsumption is needed to observe physical performance changes. Mary Z. Mays, also from the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command and formerly from USARIEM, reviews cognitive performance, emphasizing methodological issues (see Chapter 15 in this volume). Both papers conclude that weight loss of 10 percent or greater needs to be reached before performance impairment is observable, but both papers raise serious methodological questions. It appears that until it is settled how to conduct such studies (choice of subjects, tasks, measures), the "So what?" question cannot be definitively answered.

To conclude Part IV, Stephen Phinney from the University of California, Davis presents a broader medical view of energy imbalance, using examples from sports medicine rather than from military field studies in Chapter 16.

Part V deals with the eating situation, including both its physical and social aspects. F. Matthew Kramer from NRDEC reports on the eating situation as studied at NRDEC, as well as other research on this topic in Chapter 17. Howard G. Schutz from the University of California, Davis provides a method for including situational effects in attitudinal research (see Chapter 18 in this volume). His appropriateness scaling focuses on contextual issues instead of the usual sensory and hedonic focus. Franz Halberg, of the University of Minnesota, with Erhard Haus and Germaine Cornélissen, extends situational considerations to the broad issue of biological rhythms and chronobiology (see Chapter 19 in this volume). Finally, John M. de Castro from Georgia State University presents his extensive and compelling data on social facilitation of eating in Chapter 20. The dietary intake data he has collected clearly display the profound effect on eating in the presence of other people, a key issue in designing proper field feeding for soldiers who often eat alone or on the run.

John P. Foreyt, G. Ken Goodrick, and Jean E. Nelson of the Baylor College of Medicine then attempt to put underconsumption within the context of clinical underconsumption, that is, eating disorders. They explore whether eating disorder paradigms are relevant to reduced eating in nonclinical populations.

All of the above chapters identify food consumption in the military within a very broad context in which both the food and the physical and social environments exert influences. Given the military feeding environment described in early chapters, one needs to ask what can be done to enhance ration consumption by soldiers in the field. More broadly, how can eating be enhanced in general? This is an unusual question for most Americans, who are more familiar with the goal of reducing food intake.

Also at the workshop, but not included in this volume, was a panel discussion where a number of different perspectives was provided on how to enhance ration consumption. Panelist Robert Smith of Nabisco presented a customer-oriented perspective from industry. His remarks covered both product and marketing issues and heavily emphasized the soldier as customer. Howard Moskowitz, who worked at NRDEC years ago and now heads a market research firm, stressed that new technology should be used to focus on metafeatures or broad concepts in foods, not simply food products and eating situations. Cheryl Achterberg from the Nutrition Department of The Pennsylvania State University isolated a number of points raised during the meeting, such as food novelty and variety and nutrition education. She also raised the issue of marketing and treating the soldier as a customer. Achterberg drew comparisons between the military situation and the school lunch situation. Robin Kanarek of Tufts University reviewed material from the other chapters and also stressed food novelty, availability, and appropriateness.

Finally, Edward Hirsch of NRDEC presents a draft NRDEC plan in Chapter 22 that outlines an attempt to modify the military field eating situation. Hirsch's proposal is still being developed. One goal of the workshop was to re-evaluate the field feeding situation from a broader perspective in order to identify the most likely areas for improvement and fruitful research. Another goal was to share the large volume of relevant research among government, academia, and industry. It is hoped the reader will find both goals were realized.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the people who made this meeting possible. COL David D. Schnakenberg (Ret) and COL Eldon W. Askew conceived of this topic for a meeting of the Committee of Military Nutrition Research of the

Food and Nutrition Board. The staff of the Food and Nutrition Board did an excellent job with arrangements. The technical staff at the U.S. Army Natick Research, Development and Engineering Center who were speakers (Drs. Hirsch, Engell, Kramer, and Cardello) provided numerous recommendations to build an outstanding program.

REFERENCES

Hirsch, E., and F.M. Kramer 1993. Situational influences on food intake. Pp. 215–243 in Nutritional Needs in Hot Environments, B.M. Marriott, ed. A report of the Committee on Military Nutrition Research, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Hirsch, E., H.L. Meiselman, R.D. Popper, G. Smits, B. Jezior, I. Lichton, N. Wenkam, J. Burt, M. Fox, S. McNutt, M.N. Thiele, and O. Dirige 1985. The effects of prolonged feeding Meal, Ready-to-Eat (MRE) operational rations. Technical Report TR-85/035. Natick, Mass.: U.S. Army Natick Research, Development and Engineering Center.

Kramer, F.M., K. Rock, and D. Engell 1992. Effects of day and appropriateness on food intake and hedonic ratings of morning and midday. Appetite 18:1–13.

Meiselman, H.L., E.S. Hirsch, and R.D. Popper 1988. Sensory, hedonic and situational factors in food acceptance and consumption. Pp. 77–87 in Food Acceptability, D.M.H. Thomson, ed. London: Elsevier Applied Science.

DISCUSSION

PHILIP BRANDLER: You show the garrison figures, the field figures, and the reverse relationship essentially between acceptance and consumption. Have the data been analyzed to see if the acceptance model does in fact work with a constant situational environment? That is to say, given the choice between two entrees and a field environment, does acceptance lead to greater consumption even though the consumption level itself might be different, and it might be in a different situation?

HERBERT MEISELMAN: I do not know if Armand Cardello is going to cover that.

PHILIP BRANDLER: Will he talk about acceptance?

HERBERT MEISELMAN: Probably not as it relates to consumption.

PHILIP BRANDLER: I think the acceptance model will work in a simple comparison like that, but when you also change the situation, I don't think it will work.

HERBERT MEISELMAN: I agree with that, in relation to the data. The concern I have is that, in many cases, particularly with field rations, our basis for decision making is based on acceptance data. With a particular field environment we use acceptance data to select what we put into or remove from a ration. So if the acceptance model fails completely, we are using the wrong criteria.