5.

ORGANIZATION

The TOGA Program, both nationally and internationally, developed effective management, funding, and advisory structures. These structures served to plan and implement the TOGA Observing System, the making of short-term climate predictions, the TOGA COARE field program, and the research needed to support the TOGA Program. On the whole, scientists guided the program. Program managers largely followed the scientific advice.

The TOGA Program involved the acquisition and coordination, both nationally and internationally, of many different kinds of resources. These resources included continuous atmospheric and oceanic observations over the breadth of the Pacific Ocean, the regular operational atmospheric-observing system, new coupled atmosphere-ocean models, extensive supercomputer time, new data-assimilation techniques, new prediction methods, satellite data streams, and special data from process experiments. Although much less expensive than a large particle accelerator, TOGA was in the realm of “big science”, at least for the earth sciences. As such, it required the establishment of effective management and advisory structures. Though TOGA was a large program, much of the scientific direction was developed “bottom up”, from the work of individual investigators who supported the objectives of TOGA and obtained funding for projects related to the larger program.

The institutional arrangements for both the national and international TOGA Program were based on a generic tripartite management structure: a project office, an advisory mechanism, and a resource office. The project offices received advice from various panels, and received funding from the resource offices. The resource offices coordinated and gathered the funding. The project offices guided the performance of the program. Within the United States, the TOGA Project Office obtained advice from the NRC, relying on the efforts of the Advisory Panel for the TOGA Program (the TOGA Panel). The TOGA Project Office received resources through an interagency agreement under the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP). For the international effort, within the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), the International TOGA Project Office received advice from the TOGA Scientific Steering Group and obtained resources through the Intergovernmental TOGA Board. The successes of the TOGA Program—especially in deploying and maintaining the TOGA Observing System, in fostering the expansion of short-term climate prediction, in recognizing the connection between observing and

predicting, and in conducting the process studies needed to fill the gaps in our knowledge—were greatly aided by these national and international structures. These structures worked well, both individually and cooperatively.

U.S. ORGANIZATIONAL ARRANGEMENTS

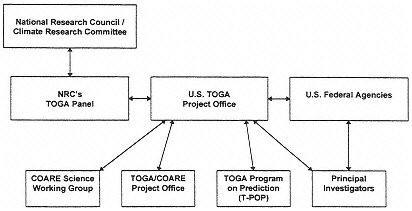

The TOGA Program in the United States expanded the basic tripartite structure of advice, resources, and administration into the structure shown in Figure 14. Advice was provided primarily by the NRC, relying on its TOGA Panel. The resources were gathered in an interagency collaboration between NOAA, NSF, and NASA. The TOGA Project Office was housed within its lead agency, NOAA, and resided at NOAA's Office of Global Programs.

NRC's TOGA Panel

While the structure shown in Figure 14 is interrelated in intricate ways, it is perhaps simplest to start with the advisory mechanism. The advice and review provided to the TOGA Project Office was provided by the NRC. The NRC relied on the efforts of its Advisory Panel for the TOGA Program (TOGA Panel), which is under the Climate Research Committee (CRC). The task statement for the Panel was written in 1983. It ordered the following:

Under the oversight of the Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, through its Climate Research Committee, and the Board on Ocean Science and Policy, the Panel will:

-

Provide regular guidance on scientific policy and priorities to the U.S. TOGA Program Office and involved agencies on behalf of the Climate Re

Figure 14. Organization of TOGA within the United States.

-

search committee (CRC). This should include Monsoon Climate Program activities.

-

Report regularly to the CRC on the Panel's involvement in U.S. TOGA plans and activities and to receive guidance from the CRC on TOGA matters in the context of the overall U.S. climate research program.

-

Advise on U.S. participation and provide the U.S. inputs to the international TOGA Program planning.

-

The members of the panel shall be selected to provide broad expertise in oceanographic and atmospheric research over all tropical oceans and the global atmosphere.

The TOGA Panel was established at the beginning of TOGA and has existed for the entire ten years of the program. It will disband upon completion of this report. Appendix A provides a list of the scientists who have given their time and energy to serve on the TOGA Panel. Questions have been raised about the number of panel members who were associated with the TOGA program, but it is not easy to determine who was part of TOGA. Although this report has largely taken an expansive view of the TOGA Program, an has included within the program domain almost all research efforts focused on ENSO or the prediction of seasonal-to-interannual climate variation, the formal designation of activities as part of the program was much more limited. If one takes this expansive view, then almost anyone who could provide for the NRC real expertise on seasonal-to-interannual climate variations was involved in the program. If one takes the narrow view that only activities supported by funds designated by federal agencies for TOGA were part of the U.S. TOGA Program, then most members of the panel did not have direct ties to the program.

The scope of the TOGA Panel's activities was limited to examinations and recommendations within the bounds of research related to ENSO. The panel did not suggest the balance of resources between those allocated for ENSO-related research and those allocated for other types of climate research. Examinations and recommendations on the place and magnitude of the TOGA Program within the broader climate-research efforts remained in the purview of the CRC. In fact, the science plan that helped launch the TOGA Program (NRC 1983) was prepared for the NRC by its more-broadly-constituted CRC, prior to the formation of the TOGA Panel. Recommendations for a follow-on program to TOGA, called the GOALS (Global Ocean-Atmosphere-Land System) Program (see chapter 7), were developed by the CRC (NRC 1994b), not the TOGA Panel.

The CRC (along with other parts of the NRC structure) has maintained oversight of the reports developed by the TOGA Panel, including this report.

Formal guidance and documentation of the TOGA Program were provided through published NRC reports. Following publication of the original scientific plan from the CRC, El Niño and the Southern Oscillation (NRC 1983), which suggested the establishment of a TOGA Program, the TOGA Panel produced a research strategy for U.S. participation in TOGA (NRC 1986). In 1989, the TOGA Panel initiated a workshop (Nova University 1989) to review the ocean observing system for TOGA, and then reported on the program's overall midlife progress and directions (NRC 1990). The TOGA Panel later spun off a panel that reported on the Observing System and methods and problems for its maintenance (NRC 1994a). The TOGA Panel is now, in this report, summing up the accomplishments and legacies of TOGA. This series of reports have proven influential in attracting attention to the TOGA Program, in giving the scientific community confidence that the program was being well run and producing good science, and in ensuring that the community at large was being well represented by the TOGA Panel in its dealings with the U.S. TOGA Project Office and the participating federal agencies. The Panel also played a major role in helping the CRC define the science for TOGA's successor program, GOALS (NRC 1994b).

More frequent informal guidance was provided through presentations and discussions at meetings of the TOGA Panel. These discussions included the Director of the U.S. TOGA Project Office, program managers from participating agencies, and members of the research community participating in TOGA. Regular reports to the CRC (item 2 of the task statement) were facilitated by having the chair of the TOGA Panel serve ex officio on the Climate Research Committee. The Panel maintained contact with the international TOGA structure (item 3 of the task statement) by having its chair and other members regularly attend meetings of the international TOGA Scientific Steering Group.

Advice is valuable only when taken. Part of the success of the TOGA Program can be attributed to the willingness of the U.S. TOGA Project Office to take seriously the advice of the NRC, and the willingness of the TOGA Panel to take seriously the problems, opportunities, and funding limitations of the Project Office. NOAA program managers, more than most others, made an active effort to test their ideas in open discussion before the TOGA Panel to obtain an informal sense of the opinions of the research community on subjects for which consensus recommendations had not been prepared. The Panel did not intend to limit its interactions other agencies, but might have become more attuned to the concerns of NOAA. On balance, the good will and close relations between the Panel and the Project Office and other agency representatives has been one of

the major reasons for the smooth running and success of the U.S. TOGA Program.

Although the job was not in its task statement, the TOGA Panel took responsibility for:

-

providing a forum for federal agencies to work together, and also for aiding the process by which agencies contributed to TOGA and obtained benefits from it, according to individual agency needs;

-

representing the larger TOGA community to the agencies and reporting back to that community any items of agency concern;

-

presenting international problems to the agencies and to the TOGA Project Office and advising them on solutions;

-

proposing the creation of new structures to carry out the TOGA Program more successfully; and

-

documenting the progress of the TOGA Program in reviewed NRC reports, so that the larger community could see and benefit from the advances of the program, and also so that, through the NRC review process, the program could have a broader base of review.

The TOGA Panel also examined the merits of and then encouraged the execution of the large TOGA Coupled Ocean-Atmosphere Response Experiment (COARE) field program in the western tropical Pacific. Sometime after the midpoint of the program, the Panel recognized that the prediction aspects of the program were lagging and that no path existed for rapid progress (NRC 1990, p. 53). The Panel recommended the creation of the TOGA Program on Prediction (T-POP). The U.S. TOGA Project Office then commissioned a meeting that undertook to write a prospectus for a possible T-POP (Cane and Sarachik 1991). The prediction community used this prospectus as the basis for a sequence of proposals submitted to NOAA. Upon review and funding of the successful proposals, T-POP was formed. The TOGA Panel has maintained regular communication with T-POP participants, and has therefore been able to coordinate prediction research with requirements for the TOGA Observing System (see NRC 1994a) and with the process studies, especially COARE, needed to fill in the gaps in ENSO understanding and prediction.

Interagency Coordination of Resources

Resources were provided to the TOGA Program in the United States through an interagency agreement, which began informally. Interagency funding requests to the Office of Management and Budget and subsequent programmatic interagency implementation proved so successful that the process served as a model for the interagency coordination embodied by the USGCRP. TOGA also became part of the USGCRP. The U.S. government Subcommittee on Global

Change Research (now a subcommittee of the Committee on Environment and Natural Resources) coordinated interagency requests to Congress for TOGA funding. The several agencies involved then granted funding to individual principal investigators and to investigator groups.

The actual coordination of funding was achieved in a number of ways. In one, the program officers from the various agencies met informally from time to time and also attended the meetings of the TOGA Panel. In another, program managers attended panels of other agencies in which competitive funding was awarded. It was not unusual for proposals submitted to one agency to be funded by a different agency (or jointly funded) because of agreements reached as a result of cross-attendance at funding panels.

The major process study of the program, TOGA COARE, used a similar structure for management and funding. A project office was set up, funding was obtained through proposals submitted to the various agencies, and a science working group was established.

TOGA Project Office

The U.S. TOGA Project Office was housed at NOAA for the duration of the TOGA Program. Dr. J. Michael Hall was its first director. Dr. Kenneth Mooney was the second director; he served until the end of the program. The Project Office coordinated the interagency support of individual principal investigators, organized science working groups (COARE and T-POP), kept the interagency budgets, and reported on a regular basis to the TOGA Panel. The director of the U.S. TOGA Project Office worked directly with the director of the International TOGA Project Office to ensure smooth integration and coordination of the national efforts with the international efforts. These coordinated efforts involved, for example, maintaining the TOGA Observing System, arranging international meetings and panels, and supporting numerical experimentation groups.

Science Working Groups

Two science working groups (SWGs) were organized by the TOGA Project Office. The TOGA COARE SWG was formed as an advisory mechanism for the massive COARE field program. The T-POP SWG was formed first as a provisional working group to define the initial outlines of the program (see Cane and Sarachik 1991). It later served as a gathering of principal investigators to coordinate the various prediction activities involved with TOGA.

COARE was such a large, comprehensive, and diverse experiment that it required its own management structure. Its advisory mechanism within the

United States was the COARE SWG, its resource office was an interagency collaboration, and it was implemented by a TOGA COARE International Project Office. The U.S. COARE SWG, assembled by the U.S. TOGA Project Office in 1988, was comprised of ten scientists, meteorologists and oceanographers from both universities and laboratories. Roger Lukas and Peter Webster co-chaired the SWG. An informal working subgroup structure was developed, with groups on large-scale circulation and waves in the oceans, large-scale circulation and waves in the atmosphere, atmospheric convection, ocean mixing, air-sea fluxes, and modeling. The two groups on large-scale circulation and waves provided the primary linkage to the overall TOGA scientific perspective. This structure proved crucial to the successful development of COARE.

The functions of the U.S. TOGA COARE SWG were to refine the scientific objectives, develop a research strategy, design the experimental approach, identify resource requirements (observing platforms, facilities, and other support), examine mechanisms for implementing the experiment, make recommendations about the coordination of research proposals, and establish, in cooperation with the TOGA Scientific Steering Group (SSG), the international framework for the experiment. The SWG worked closely with international colleagues to write the COARE Science Plan (WCRP 1990) and to develop the Experiment Design for COARE (TCIPO 1991), and worked with the TOGA COARE International Project Office (TCIPO), after it was established in 1990, to develop the Operations Plan for COARE (TCIPO 1992).

The SWG was not intended to last through the field phase and into the analysis and synthesis phases of TOGA COARE. This was, perhaps, an oversight. It became clear that continuing guidance and oversight were needed to achieve climate-prediction benefits from the substantial investment in COARE. With the formal end of TOGA, the full analysis of the data from TOGA COARE is in jeopardy. The 1994 COARE data workshop in Toulouse, after considerable discussion, determined that to produce a final, quality-controlled data set, funding will be required through at least 1998 (TCIPO 1995). This schedule is consistent with experience from previous large field programs. However, it is not obvious how such funding can be sustained, especially because resources devoted to TOGA will not necessarily be continued intact to its successor program, GOALS.

Coordination with International TOGA.

No program dealing with the climate of major parts of the globe could possibly be accomplished without international coordination and cooperation. The U.S. TOGA Program had a significant involvement with international organizations. In order to assure smooth coordination between the national and international

organizations, the U.S. TOGA Project Office seconded several people to work in the International TOGA Project Office, and also partially funded the staffing of the international office.

The NRC's CRC became the official liaison between the U.S. science community and the WCRP because one of the sponsors of the WCRP is the International Council of Scientific Unions, to which the National Academy of Sciences* belongs. The TOGA Panel was designated by the CRC to serve as its liaison with the International TOGA SSG.

In addition to the multinational arrangements, the United States entered into bilateral agreements with other countries to develop and maintain certain observing-system elements. In particular, the United States sustained a bilateral agreement with New Zealand for the maintenance of the upper-air station at Canton Island (now closed). Agreements were made with France and Australia for the maintenance of lines of ship-launched expendable bathythermographs. The United States entered into agreements with the People's Republic of China and with Indonesia for collaboration in the western Pacific and in measurements for TOGA COARE.

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONAL ARRANGEMENTS

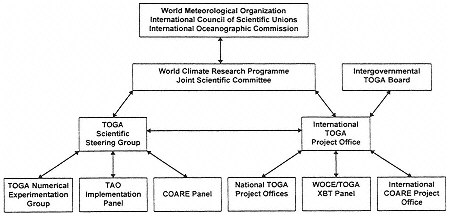

The International TOGA Program was coordinated under the auspices of the WCRP. Several specially created entities then developed the program specifics for TOGA. Resources were arranged by the Intergovernmental TOGA Board. The TOGA SSG served as the advisory body and the International TOGA Project Office organized the implementation (see Figure 15).

TOGA as an Integral Part of the WCRP

Following directly from the highly successful Global Atmospheric Research Program (GARP), the WCRP was initiated at the end of 1979. The initiation was formalized by an agreement between the World Meteorological Organization (WMO, a specialized agency of the United Nations), and the nongovernmental International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU). The Joint Organizing Committee (JOC) for GARP subsequently metamorphosed into the Joint Scientific Committee (JSC) for the WCRP. The major objective of the WCRP is to determine the extent to which climate can be predicted and the extent of man's influence on climate. WCRP initiatives are concerned primarily with time scales from several weeks to several decades. An examination of the WCRP, with an emphasis on U.S. participation and including a chapter on the

Figure 15. International organization for TOGA.

role of TOGA within the larger international program, was the subject of a 1992 NRC report.

At the inception of the WCRP, the ICSU Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR) and the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization) Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) established the Committee on Climatic Changes and the Ocean (CCCO) to facilitate the involvement of the international oceanographic community in WCRP planning. The CCCO worked in collaboration with the JSC until the CCCO was disbanded at the end of 1992. In 1993, the IOC joined WMO and ICSU as a joint sponsor of the WCRP, and the membership of the JSC was expanded accordingly.

Early consultations between the JSC and the CCCO led to the formation in 1981 of a joint JSC/CCCO study group on the interannual variability of the tropical oceans and global atmosphere. The study group sought to build on national efforts, most notably the TOGA Program that was then evolving in the United States, to define a program on interannual variability. The joint JSC/CCCO Study Conference on Large-Scale Oceanographic Experiments in the WCRP, held in Tokyo during May 1983, afforded the first opportunity for extensive international discussions of TOGA as a possible element of the WCRP. The conference concluded that the TOGA Program was feasible, that it should be an integral part of the WCRP, and that it should be organized as soon as possible.

The conference also recommended that the World Ocean Circulation Experiment (WOCE), then developing in the United States, should be expanded as

a major activity within the WCRP. Together, TOGA and WOCE have constituted the major oceanographic efforts of the WCRP. For the most part, they complemented each other. Overlapping requirements in their respective implementation plans for a number of oceanographic observations encouraged some coordinated efforts, notably for certain expendable-bathythermograph, drifting-buoy, and tide-gauge data, together with the associated data-management activities. For this reason, close liaison was maintained between the two international programs at the levels of the scientific steering groups and project offices. This cooperation extended to joint sponsorship of the TOGA/WOCE XBT/XCTD (expendable bathythermograph / expendable conductivity-temperature-depth probe) Program Planning Committee and the WOCE/TOGA Surface Velocity Program Planning Committee.

Scientific Steering Group (SSG)

In early 1983, a joint JSC/CCCO TOGA SSG, chaired by Adrian Gill, was established. The TOGA SSG formulated the overall international program. It developed the concept of the TOGA Observing System and provided scientific guidance for its implementation. The SSG assumed responsibility for leading and coordinating the work of the three CCCO Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Ocean Climate Studies Panels. As TOGA developed, the SSG ensured the exchange and analysis of TOGA data and the dissemination of scientific results. To provide overall scientific guidance for COARE, the TOGA SSG established the international TOGA COARE Panel, which worked closely with the U.S. COARE Science Working Group.

The SSG met for the first time during August 1983 at the Max Planck Institute für Meteorologie in Hamburg to initiate plans for the preparation of the TOGA Scientific Plan. It organized the International Conference on the TOGA Scientific Program, which was held in Paris during September 1984. The first draft of the Scientific Plan for TOGA was distributed at the Paris conference. The final version was published by the WCRP in September 1985. Throughout its lifetime, the SSG maintained a close relationship with the U.S. TOGA Panel.

Scientific advice at the international level was also provided by the International TAO Implementation Panel. It was convened to coordinate the Tropical Atmosphere/Ocean (TAO) Array, a collection of moorings in the tropical Pacific that served as a cornerstone of the TOGA Observing System. The TAO Implementation Panel brought the various users of TAO array information together. Progress and problems with the array and its instruments were assessed and reviewed, with an eye towards improving the analysis of the TAO observations and commenting on the adequacy and accuracy of the array itself.

International Project Office

At its first meeting, the TOGA SSG formally established the International TOGA Project Office (ITPO) and accepted the U.S. offer to host the ITPO. The ITPO prepared detailed plans for the various observational components of TOGA, for data processing, and for the production of reference data sets. It also assisted with the preparation of TOGA documents and with other organizational tasks.

The ITPO was located in Boulder, Colorado, from 1984 until its move to Geneva in 1987. When in Boulder, the ITPO was supported primarily by the United States, with additional personnel seconded by France and India. Rex Fleming and James Lyons served as the first two directors, while the office was in Boulder. When in Geneva, the ITPO was supported by the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the WMO, with personnel seconded by France. John Marsh served as director while the office was in Geneva. The support of the ITPO by the United States was a U.S. contribution to the management of the TOGA program.

The ITPO (Boulder) produced the first edition of the International TOGA Implementation Plan in 1985. The second edition followed in 1987. Further editions, which reflected significant contributions of resources from many nations, were produced by the ITPO (Geneva) in 1990 and 1992. The Implementation Plan relied on such observing systems as the WMO's World Weather Watch (WWW) and the IOC's Global Sea-Level Observing System (GLOSS). In addition to these ongoing efforts, and the special efforts of the United States, contributions came from Australia, France and Japan for the VOS XBT program; contributions came from France, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan for the TOGA TAO array of moorings in the western Pacific; contributions came from Australia, France, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan for the Surface Velocity Program; and Ecuador, the Maldives, Papua New Guinea, and the Republic of the Yemen operated key TOGA upper-air stations.

In accordance with the TOGA Data Management Plan, which was an integral part of the International TOGA Implementation Plan, TOGA data centers were operated by European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting, France, India, and the United Kingdom. These data centers worked in concert with the TOGA Global Sea Surface Temperature Data Center and TOGA Sea Level Data Center established in the United States (at the Climate Analysis Center of the National Meteorological Center* and the University of Hawaii, respectively).

A separate project office was established in Boulder for the large COARE field program. The office moved to Townsville, Australia, during the Intensive Observation Period. The TCIPO supported the ongoing planning for TOGA COARE and coordinated international implementation. The TCIPO worked with the TOGA COARE Panel for the purpose of preparing and then updating the international TOGA COARE Operations Plan (TCIPO 1992), to coordinate national commitments of resources in relation to the implementation plan, to develop and implement a logistics support plan for the field phase of COARE (TCIPO 1993), to develop and implement a specific data management plan for COARE, and to coordinate information among scientists, national agencies, and appropriate international bodies. The TCIPO was headed by David Carlson, who saw to the efficient operation of the office, provided general leadership to conduct the COARE field phase, and oversaw the data-management plan. The TCIPO published a summary of the observations made during the Intensive Observing Period of COARE. The office closed in June 1996 after the last director, Richard Chinman, finished supervising final data processing and distribution.

Intergovernmental TOGA Board

Following recommendations from the first informal planning meeting on the WCRP, held in Geneva during May 1986, the WMO and IOC established the Intergovernmental TOGA Board in 1987. The principal objectives of the board were to review the requirements for the implementation of TOGA, to provide a forum for intergovernmental consultations to ensure coordination of national resources that might be applied to the TOGA Program, to review progress made in implementing TOGA, to identify gaps that might appear in the implementation of TOGA, and to take action, as appropriate, to fill these gaps. Fourteen nations closely allied with TOGA were originally represented on the board; they were joined later by four others. The final national representation consisted of Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Ecuador, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Japan, Mauritius, New Zealand, Pakistan, Peru, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the U.S.S.R.

At the second meeting of the Intergovernmental TOGA Board in December 1988, the U.S. representative informed the board of the U.S. planning undertaken COARE. The board formally adopted COARE as an integral part of TOGA. The TOGA COARE Science Plan was published by the WCRP as an addendum to the Scientific Plan for TOGA (WCRP 1990). In addition to the United States, many nations (notably Australia, China, France, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom) made significant contributions of personnel and equipment to COARE. These resources enabled a far more

ambitious field program to be designed than would have been possible had U.S. assets alone been involved.

At its final meeting in April 1993, following discussions initiated by U.S. representatives at previous meetings, the Intergovernmental TOGA Board noted the strong statements of support for and interest in directly participating in various aspects of an International Research Institute for Climate Prediction (IRICP). This proposal had emanated from a NOAA study group with international representation. The TOGA Board requested that the United States continue to take the lead in developing an IRICP proposal by convening a broad high-level meeting of interested nations to consider the creation of such an institute and to begin its implementation. These efforts are described in Chapter 7.