Chapter 3

Outcomes, Costs, and Incentives in Schools1

ERIC A. HANUSHEK

University of Rochester

The production of school reform reports is big business in the United States The current push for reform is commonly traced to A Nation at Risk, the 1983 government report that detailed the decline of America's schools (National Commission on Excellence in Education, 1983). Since its publication, new reports have come so frequently that it is rare for a major institution not to have its own report and position on education reform. Yet it is startling how little any of the reports, or the reform movement itself, draw upon economic principles in formulating new plans. At the same time, little appears to have been accomplished in terms of fundamental improvements in the nation's schools.

The movement to reform our schools is motivated in large measure by economic issues. Concerns over the strength of the U.S. economy, the incomes of our citizens, and gaps between the standards of living for different racial groups are consistently grounded in questions about the quality of our schools. A parallel issue seldom addressed in the reform reports but increasingly a matter of public concern is whether the steady increase in funds devoted to schools is being used effectively. These economic issues are at the core of interest in and apprehension about the state of the nation's schools.

Not only are economic results a key motivation for improvement, but economic principles are an essential means of achieving improved performance of the education system. Economists have studied the role that education plays in developing worker skills since before the United States declared its independence and have learned a great deal on the subject. More recently, economists have

considered how schooling affects such diverse things as the character of international trade and the choices families make about investments in their own health. The results of this work have not been adequately incorporated into the nation's thinking and policies toward schools. Most strikingly, standard economic principles are seldom applied to policymaking or to the administration of schools.

This paper grows out of the efforts of a panel of economists to bring economic thinking in its various forms to the reform of American schools.2 Its purpose is to develop the policy conclusions that logically flow from existing evidence about the role and operation of schools. It does not point to a specific program or reorganization of schools that will solve all of the problems, in part because single answers do not appear to exist. Instead, it points to an overall approach, strengthening performance incentives, and a set of decision rules, comparing benefits with costs, that have proved extremely useful in enhancing business performance, even if they have been largely ignored by schools. It also highlights the necessity of learning from experience enriched by a well-designed program of experimentation. These ideas seem noncontroversial, yet they are noticeable in their absence from current education debate and policy.

Reform—in education as in other areas—is often thought of as the process of securing more resources. Here our panel breaks with tradition. Analysis of the history of schools in the twentieth century does not suggest that American society has been stingy in its support of schools. Quite to the contrary, funding for schools has grown more or less continuously for 100 years. The fundamental problem is not a lack of resources but poor application of available resources. Indeed, there is a good case for holding overall spending constant in school reform. Not only is there considerable inefficiency in schools that, if eliminated, would release substantial funds for genuine improvements in the operation of schools, but there also is a case for holding down funding increases to force schools to adopt a more disciplined approach to decisionmaking. Schools must evaluate their programs and make decisions with student performance in mind and with an awareness that trade-offs among different uses of resources are important.

The plan is not a substitute for goals and standards—the centerpiece of much recent policy discussion—but a way of achieving those goals. In simplest terms, the identification of curriculum, assessment, and achievement goals will not in any automatic way lead to achieving them. Instead, new and different approaches that actively involve students and teachers in attaining these goals are required.

Why Society Worries About Education

Because the system of schooling allows little room for individual preference or competition among alternative suppliers and because of the special nature of education in the economy, there is no guarantee that society's interests are best served. The central questions are straightforward: Are we as a nation investing the right amount in schooling, and are the resources devoted to schooling being used in the best possible way?

Economists tend to focus on the trade-offs between alternative uses of resources. Money spent on schools cannot be used for buying health services, consumer goods, or national defense and vice versa. Economists do not devote much attention to evaluating choices that individual families make, such as whether to purchase a television or a car, because it is assumed that individuals make informed choices about things that directly affect them. But when government is heavily involved in the decisionmaking, the possibility of under- or overinvesting is more likely. Moreover, if resources are not used effectively, as is more likely when there is little competition, society gives up too many other things to get its schooling.

Analysis demonstrates clearly that education is valuable to individuals and society as a whole. The economy values skilled individuals, and this is reflected directly in the high relative earnings in the labor market and low relative unemployment rates of the more educated. Over the past two decades, the earnings advantages associated with more schooling have soared.3 These facts on their own justify general investment in schooling, but they are only part of the story. More educated members of society are generally healthier, are more likely to become informed citizens who participate in government, are less likely to be involved in crime, and are less likely to be dependent on public support (Haveman and Wolfe, 1984; and Wolfe and Zuvekas, 1994). Moreover, the education level of the work force affects the rate of productivity growth in the economy and thus the future economic well-being of society (Lucas, 1988; Romer, 1990; and Jorgenson and Fraumeni, 1992). These latter factors, while further justifying schooling investments, also provide reasons for government financial support of education (as opposed to purely private financing), because individuals cannot be expected to take them sufficiently into account in making their own schooling decisions.

Why then, if schooling has been such a good investment, is there so much concern, consternation, and outright dissatisfaction with our schools? Much of

the analysis of the effects of education on earnings and the economy relates exclusively to the amount of schooling obtained by the population. The previous growth in school attainment of the population has virtually stopped, however, and with it the debate has shifted to quality differences. In simplest terms, the issues have centered on whether students are learning sufficient amounts during each year of schooling and whether the distribution in learning outcomes across individuals is appropriate and desirable from society's point of view.

The strongest evidence about the effects of school quality relates to individual earnings. Higher cognitive achievement, which is directly related to school quality, is rewarded through higher wages. There is also evidence that such skills are becoming more important over time as an increasingly technical workplace looks for people to fill jobs.4 Finally, school quality directly affects the amount of schooling an individual completes, with students from better schools seeking postsecondary education and thus enjoying the added rewards of increased schooling. These benefits again justify investments in school quality.

It is also important to understand some of the macroeconomic implications of schooling investments because the public debate has been particularly confused about these issues. In the past quarter century, as questions have been raised about what is happening in schools, the national economy has also gone through extraordinary changes. The rate of increase in the productivity of the labor force, an important determinant of the economic well-being of society, fell dramatically in the 1970s and the 1980s. The importance of international trade over this period dramatically affected the U.S. economy, causing some citizens and policymakers to be alarmed about our ability to compete internationally as foreign producers have taken over markets previously dominated by U.S. firms. And, most recently, the economy has languished with slow growth of the gross domestic product.

Which of these issues are related to the perceived falling quality of schools during this period, and which are likely to be turned around by quality improvements? Current research suggests that school quality helps determine the overall productivity growth of the national economy, although there is considerable uncertainty about the exact magnitude of the effect. It is clear that past decreases in productivity could not have been caused by the recent declines in student performance, because these students were not in the labor force in sufficient numbers to have influenced the observed productivity changes.5 Any direct effects of current student quality on national productivity growth will be felt only at some time in the future. Moreover, the direct effects of changes in American school quality on the level of trade deficits or on the character of international trade are almost

surely very small, since international trade is driven much more by comparative advantage and other aspects of world economies that evolve slowly. Finally, there is no reason to believe that business cycles and macroeconomic fluctuations are influenced by the schooling of the labor force. Thus, claims about the effects of schooling, past or future, on the overall aggregate performance of the economy appear exaggerated and do not provide direct justification for significant expansions in public schooling.

In sum, schooling is important. Investing in more and better schooling has been profitable for individuals and society. The case for supporting education is not without bounds, however. Other investments, such as in more modern plants and equipment, also have significant payoffs, so that the potential for schooling investments should be kept in perspective. Benefits must be compared to costs. Moreover, even a perfectly functioning school system will not solve all problems of society and the economy.

The change in focus from how much schooling individuals receive to how good the schooling is is also important to policy deliberations. The economic and social returns to more years of schooling do not translate easily into arguments for specific policies or spending actions related to improving the quality of schools (Hanushek, 1995). The latter issue lies at the heart of today's discussions.

What is Known about Schools

A considerable body of documentation has been gathered about the economics of the education sector itself. Education is, after all, a sector that is noticeably larger than, say, steel or automobiles, and, as noted, it has strong links to other parts of the economy. As such, education has received its share of analysis and attention. The results of this economic analysis have, at best, been ignored, and at worst contradicted, in many of the popular versions of school reform.

The overall story about what has been happening in schools is clear: the rapid increases in expenditures for schools of the past three decades have simply not been matched by measurable increases in student performance. Moreover, detailed studies of schools have shown a variety of inefficiencies, which, if corrected, could provide funds for a variety of improvement programs.

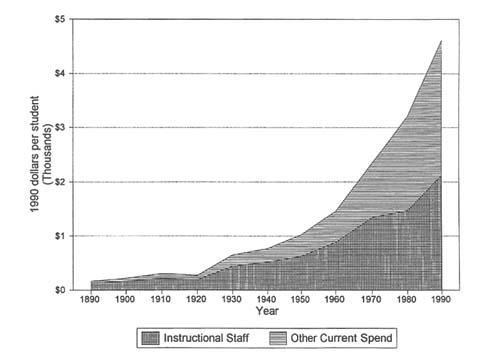

There has been a dramatic rise in real expenditure per pupil over the entire century. Figure 3.1 shows that, after allowing for inflation, expenditures per pupil have increased at almost 3.5 percent per year for 100 years (Hanushek and Rivkin, 1994). This remarkable growth is not explained away by such things as increases in special education or changes in the number of immigrant students in the school population, although these factors have had a noticeable impact on school expenditures.

The spending increases have been driven by three basic factors. In terms of direct instructional staff expenditures, both declines in pupil-teacher ratios and increases in the real salaries of teachers have been very important. These two

FIGURE 3.1 Real expenditures per pupil, instructional staff and other spending, 1980–1990.

elements are the primary elements behind the lower portion of the graph in Figure 1, which plots instructional staff and other expenditures per student. Throughout the century, teachers have been used more intensively, as a result of both direct efforts to reduce class size and the introduction of new supplementary programs that expand on teacher usage. Real teacher salaries have also grown, although in a somewhat complicated way. The increases in teacher salaries have not been uniform, as periods where salaries have not kept up with inflation are offset by periods of more rapid increase. Moreover, even with general improvement, salary growth has not kept up with the growth in salaries for college-educated workers in other occupations. Thus, while teachers' wages have put cost pressure on schools, school salaries have been competitive with a smaller proportion of outside jobs over time.6

The top portion of Figure 3.1 identifies in a general way the third source of cost increases. Expenditures other than those for instructional staff have increased even more rapidly than those for instructional staff. Between 1960 and 1990, instructional staff expenditures fell from 61 percent to 46 percent of total current expenditures. Unfortunately, what underlies this is unclear, because there are very poor data on those expenditures. While it is often convenient to label this simply "increased bureaucracy," the available data neither confirm nor deny this interpretation, because these expenditures include a variety of items that are legitimate classroom expenditures (such as teacher health and retirement funds or purchases of books and supplies), in addition to administrative and other spending. The aggregate effects are clear, however; if these expenditures had grown between 1960 and 1990 at just the rate of instructional staff spending—which itself includes significant increases in resource intensity—total spending per pupil would have been 25 percent lower in 1990.

The pattern of spending changes in recent years points to an upcoming fiscal crisis for the nation's schools. During the 1970s and 1980s, the U.S. student population fell dramatically. During that time, increases in per-pupil expenditures were offset by falls in the student population, so that aggregate spending on schools rose much more slowly than per-pupil expenditures (Hanushek and Rivkin, 1994). But the situation is now changing, and the student population is again rising. As rising student populations combine with growth in real spending per student, aggregate spending will be up at a much higher rate than over the past decade. These prospective expenditure increases are likely to collide with public perceptions that school performance is not rising. If this happens, local taxpayers, who continue to play an important role in American school finance, are likely to resist future expenditure increases with unprecedented insistence, perhaps putting schools into a real fiscal squeeze. Moreover, many major urban districts face fiscal pressures from competing demands for public revenues, such as welfare or police funding, suggesting that the worst of the fiscal crisis might appear in the already pressured schools of major cities.

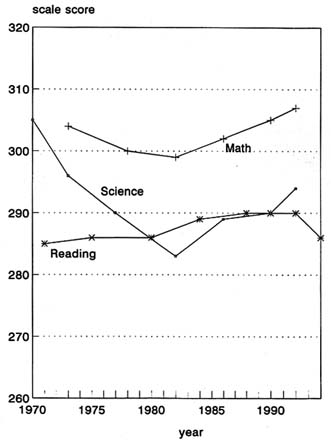

Matched against the growth in spending, student performance has, at best, stayed constant and may have fallen. While aggregate performance measures are somewhat imprecise, all point to no gains in student performance over the past two decades. The path of achievement on reading, math, and science exams, shown in Figure 3.2, provides a visual summary of the pattern of performance for the population (U.S. Department of Education, 1994). These figures display the performance over time of a representative sample of 17-year-olds on the various components of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). While there has been slight movement, the overall picture is one of stagnating performance. Moreover, since substantial decline occurred before the beginning of these series (see Figure 3.3, below), this chart understates the magnitude of the problem.

There has also been a series of embarrassing comparisons with students in

FIGURE 3.2 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), performance of 17 year olds, 1970–1994.

other countries. Comparisons of U.S. and Japanese students in the early 1980s showed, for example, that only 5 percent of American students surpassed the average Japanese student in mathematics proficiency (McKnight et al., 1987, and National Research Council, 1989). In 1991 comparisons, Korean 9-year-olds appeared closer to U.S. 13-year-olds than to U.S. 9-year-olds, hardly the kind of performance that would put U.S. students first in the world in mathematics performance (U.S. Department of Education, 1994).

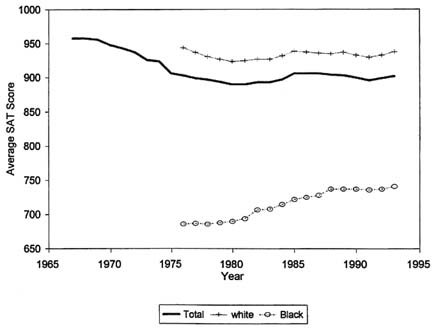

The problems of performance are particularly acute when considered by race or socioeconomic status. Even though there has been some narrowing of the differences in performance, the remaining disparities are huge and incompatible with society's goal of equity. Figure 3.3, for example, displays the history of

FIGURE 3.3 SAT scores: total and by race, 1966–1993.

SAT performance over two decades. These scores quite convincingly display a disparity that mirrors one also existing on the NAEP tests. 7 During the 1980s, there was a broad-based convergence of black-white score differences, but most recent data suggest that it may have ceased.

The aggregate results, showing that expenditure increases have not been accompanied by improvements in student performance, are confirmed in more detailed studies of schools and classrooms (Hanushek, 1986 and 1989). These more detailed studies document a variety of common policies that increase costs but offer no assurances of commensurate improvements in student performance. The wide range of careful econometric studies reviewed in Hanushek (1989) indicate that key resources—ones that are the subject of much policy attention—are not consistently or systematically related to improved student performance.

Perhaps the most dramatic finding of analyses of schools is that smaller class sizes usually have had no general impact on student performance, even though they have obvious implications for school costs. Moreover, the basic econometric evidence is supported by experimental evidence, making it one of the clearest results from an extensively researched topic.8 Although some specific instruction may be enhanced by smaller classes, student performance in most classes is unaffected by variations in class size in standard operations of, say, 15 to 40 students.9 Nevertheless, even in the face of high costs that yield no apparent performance benefits, the overall policy of states and local districts has been to reduce class sizes in order to try to increase quality.

A second, almost equally dramatic, example is that obtaining an advanced degree does little to ensure that teachers do a better job in the classroom. It is just as likely that a teacher with a bachelor's degree would elicit high performance from students as would a teacher with a master's degree. Again, since a teacher's salary invariably increases with the completion of a master's degree, this is another example of increased expenditures yielding no gains in student performance. 10 The final major resource category with a direct impact on school spending through salary determination is teacher experience. The evidence on the effectiveness of experienced teachers is more mixed than for the previous categories, but it does not provide convincing support of a strong relationship with performance.

These resource effects are important for two reasons. First, variations in instructional expenditures across classrooms are largely determined by the pupil-teacher ratio and the salary of the teacher, which, in turn, is largely determined by the teacher's degree and experience. If these factors have no systematic influence on student performance—which the evidence shows they do not—expansion of resources in the ways of the past are unlikely to improve performance. Second, either explicitly or implicitly schools have pursued a program of adding these

TABLE 3.1 Public School Resources, 1961–1986

|

Resource |

1960–61 |

1965–66 |

1970–71 |

1975–76 |

1980–81 |

1985–86 |

1990–91 |

|

Pupil-teacher ratio |

25.6 |

24.1 |

22.3 |

20.2 |

18.8 |

17.7 |

17.3 |

|

% Teachers with master's degree |

23.1 |

23.2 |

27.1 |

37.1 |

49.3 |

50.7 |

52.6 |

|

Median years experience of teacher |

11 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

12 |

15 |

15 |

|

Current expenditure/ADA (1992–1993 dollars) |

$1,903 |

$2,402 |

$3,269 |

$3,864 |

$4,116 |

$4,919 |

$5,582 |

|

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education (1994). |

|||||||

specific resources.11 Table 3.1 traces these resources over the past several decades. Schools currently have record-low pupil-teacher ratios, record-high numbers for completion of master's degrees, and more experienced teachers than at any time at least since 1960. These factors are the result of many specific programs that have contributed to the rapid growth in per-pupil spending but have not led to improvements in student performance. Schools do not try to ensure that increased student performance flows from increased expenditures.

Interestingly, Marshall Smith's summary of the evidence on schools in this volume concedes that it is common knowledge that variations in resources are unconnected to student performance. Further, he criticizes research aimed at identifying the relationship of resource variations with student performance. Yet, in my view, one objective of public policy ought to be to ensure that public resources devoted to schools are used effectively. Nothing in today's school finance system, save perhaps the ultimate rejection of school budgets, pushes schools to promote efficient use of resources. Unless significant changes occur, there is little reason to believe that additional resources applied in the future will be used any better than resources applied in the past.

Although there is no consensus about which specific factors affect student performance, there is overwhelming evidence that some teachers and schools are significantly better than others. For example, in inner-city schools, the progress of students with a good teacher can exceed that of students with a poor teacher by more than a year of achievement during a single school year.12 The dramatic differences in performance are simply not determined by the training of teachers,

the number of students in the classroom, or the overall level of spending. A primary task of school reform is increasing the likelihood that a student ends up in a high learning environment.

The lack of relationship between resources and performance surprises many people but perhaps should not. The most startling feature of schools, distinguishing them from more successful institutions in our economy, is that rewards are only vaguely associated with performance, if at all. A teacher who produces exceptionally large gains in her students' performance generally sees little difference in compensation, career advancement, job status, or general recognition when compared with a teacher who produces exceptionally small gains. A superintendent who provides similar student achievement to that in the past but at lower cost is unlikely to get rewarded.13 With few incentives to obtain improved performance, it should not be surprising to find that resources are not systematically used in a fashion that improves performance.

The current inefficiencies of schools, with too much money spent for the student performance obtained, indicate that schools can generally improve their performance at no additional cost. They simply need to use existing resources in more effective ways. These inefficiencies also indicate that continuing the general policies of the past, even if dressed up in new clothing, is unlikely to lead to gains in student performance, even though cost pressures will continue to mount.14 It may be appropriate to increase spending on schools in the future, but the first priority should be restructuring how existing resources are being used.15

What Might Be Done

One common response to the evidence of pervasive inefficiencies, often linked to appeals for added spending, is that ''if we spend money effectively, we can improve student performance." This tautological statement is just the concern. History suggests that spending money on effective programs will not happen naturally or automatically in the current structure of schools. Our panel of economists sees no reason to believe that increases in spending would on

average be any more effective than past spending, particularly when they rely on the same people operating with the same basic incentives.

Three key principles, our panel believes, are essential to improving U.S. Schools:

- resources devoted to education must be used efficiently;

- improved performance incentives must be introduced in schools; and

- changes must be based on systematic experimentation and evaluations of what does and does not work.

These principles, which appear to be based on common sense and do not seem controversial, are most notable in their virtual absence from today's schools and today's policy setting.

Efficiency

Any reform program must explicitly consider the costs as well as the potential benefits of changes. Efficiency simply relates to the quest to get the largest benefits from any spending. Virtually all past considerations of school reform, on the other hand, have either ignored costs or argued that the benefits are large enough to support any proposed increase in costs. The disregard for costs leads to distorted decisions. Ultimately, this view undoubtedly lowers the likelihood that any proposals will be taken seriously, because policymakers and the public will consider the price tag attached to any major restructuring of schools. As indicated above, however, attention to both costs and benefits should not be restricted to new programs. Many existing programs are inefficient and should be replaced by more cost-efficient ones.

Mention of efficiency is often met by disdain from school personnel, in part because of general misunderstanding of what efficiency means. It is neither a mandate to minimize costs without regard to outcomes nor a narrow view of what schools are expected to accomplish. Instead, it is a recognition of the competition for resources both within schools and elsewhere in society. Moreover, schools are likely to run into greater and greater difficulties in raising funds, especially if they are unable to show results.

Performance Incentives

Incentives based upon student outcomes hold the largest hope for improving schools. Most past policy has been based on a combination of regulations and fixed definitions of inputs to schooling—the resources, organization, and structure of schools and classrooms. Little attention has been focused on the results. Improvement is much more likely if policies are built on what students actually accomplish and if good performance by students gets rewarded. If properly designed, performance incentives will encourage the creativity and effort needed to develop and implement effective programs.

Education is a very complicated task that requires the cooperation and ingenuity of individual teachers, principals, and other school personnel.16 It is, moreover, virtually hopeless to think of running a high-quality education system without the active involvement of students. Finally, there are many equally effective approaches to learning various subjects and skills, differentiated by how individual teachers and students adapt to specific tactics and techniques. If there is no single-best approach to performing specific educational tasks, it is simply not possible to design policies that are based on full descriptions of what is to be done and how it is to be done in the classroom.

The policy suggestions of our panel of economists differ from most previous school reform documents. We do not recommend a specific program or a major restructuring of schools. Current knowledge does not support a lot of specific prescriptions or broad recommendations. Indeed, we have every reason to believe that many different approaches might be used simultaneously in an effective school system. On the other hand, certain strategies for reforms are very clearly more beneficial, and it is these that our panel emphasizes. Strategies involving improved incentives, ongoing evaluation, transmission of performance information, and consistent application of rational decision rules are central to any productive reform path.

As Marshall Smith and his colleagues at the U.S. Department of Education suggest, implementation of performance incentives requires having explicit goals and developing measures of performance that relate to those goals. Improving schools is currently made very difficult by the lack of generally agreed upon measures of performance. And quite clearly, developing incentive systems must include consensus about how good performance is defined and subsequently rewarded. Nonetheless, our panel does not see a test-driven management of schools but instead a reform that incorporates a variety of performance observations. Similarly, as discussed below, we do not see that simply announcing high goals and developing commensurate standards are likely by themselves to lead to accomplishing those goals.

A wide range of incentive structures offer hope for improving schools. These systems are the subject of much heated debate and frequently bring forth emotional responses. The alternatives, along with their pros and cons, are spelled out in detail elsewhere (Hanushek et al., 1994). The essential feature of all of them, however, is that resources and rewards are directed at good student performance and away from bad performance. The commonly discussed plans do this in quite different ways. For example, performance contracting involves developing explicit contracts that base rewards on meeting various performance goals, while merit pay plans take the basic structure of existing schools and attempt to alter the

compensation scheme for teachers to conform more with student outcomes. Alternatively, clearer hiring, promotion, and retention policies for teachers on the basis of classroom performance are related to a private school model of the personnel system. Merit school programs build in shared rewards for people in high-performance schools, lessening any tendencies for unhealthy competition among teachers. Going in a different direction, a variety of school choice schemes highlight the potential importance of individual student decisions about which school to attend. Choice systems come in many different forms. Some may leave much of the current structure of school systems intact (such as magnet school programs or intradistrict choice plans), while others may begin to shake the existing foundation of schools (such as interdistrict choice or public-private vouchers). Each of these incentive systems conceptually focuses attention and incentives on student performance, either through school evaluations or parental involvement. As a group, they also differ significantly from the way schools are currently organized.

The most remarkable fact about the range of conceptually appealing performance incentives is that they remain virtually untested. Few examples of their use are available, and, as with the vast majority of new programs instituted in schools, attempts to introduce these various incentive systems are seldom evaluated in any systematic manner. We know neither what forms of incentive systems are best in general or specific circumstances nor precisely what results might be expected from broader use of any specific system. The impotence of current incentives coupled with the observed power of incentives elsewhere in the economy, however, lead our panel to believe that one or more of these alternative incentive schemes could be productively instituted and adapted to virtually every school system in the country. Finding the best set for individual systems will require effort, but the potential for improvement supports undertaking such a quest.

In addition to these incentives directed at schools, it is important to think of incentives directed at students. While the previous discussion emphasized the general lack of performance incentives for teachers and school personnel, the lack of incentives is not limited to them. Students who work hard and perform well in schools typically see only minor differences in rewards when compared with students who do not work hard and who do not perform well. Potential employers, for example, seldom gather any information about the scholastic performance of applicants, and, except for the limited number of highly selective colleges and universities, variations in student performance across a fairly wide range have little impact for postsecondary school attendance. More significant performance incentives for students could reinforce and amplify performance incentives for school personnel.17

Evaluation and Experimentation

This lack of knowledge about performance systems calls for a broad program of experimentation and evaluation, the third major component of the decision process proposed here. Improvement on a large scale will be possible only with the development of a knowledge base about effective approaches. Remarkably, evaluation is seldom an integral part of schools today. Any evaluation that is done is much more likely to occur before a program is introduced, rather than after.18 Schools, while recognizing the importance of regular evaluation in the case of their students, avoid evaluation of their own performance.

This is a call for more experimentation and integrated evaluation rather than for more research on schools as they are currently organized. Experimentation would be directed at encouraging wider development and use of new incentive structures. Simply introducing performance incentives is clearly risky because some versions of incentive systems will not work as hoped or predicted.

We must be able to disseminate and build on good results. Evaluation is difficult because it is essential to disentangle the various influences on student performance. Schools and teachers are just one factor that affects student learning. The students and their parents directly influence performance, as do other students and other members of the community. All too often people confuse high absolute levels of performance by students with high performance by schools, not recognizing that schools might be contributing little to students' performance in some situations. Similarly, just the opposite occurs where particular teachers and schools do an exceptional job that goes unrecognized because the overall level of student achievement is low. Both situations lead to poor policies. Evaluation must concentrate on extracting the value-added of schools and linking this value-added to the programs and organization of the schools.

Reform Principles and the Current Policy Debate

The general principles of reform described here have much in common with the current systemic reform movement, but it is easy to overlook essential differences.

Decentralized Decisions—Past and Future

Any improved system will have to harness the energy and imagination of the personnel in the local schools. If incentives are instituted to reward performance,

school personnel must have the freedom to institute the programs and approaches that will best enhance student performance. The specific approaches will almost certainly differ across schools and teachers, even if everybody face the same reward structure for student performance. This argues for decentralization of decisionmaking. Some form of site-based management is likely to be an important ingredient of new incentive systems.

A current popular approach to site-based management is not fully consistent with the ideas here because it is not directly linked to student performance (Summers and Johnson, chapter 5, this volume). Decentralization of decisionmaking has little general appeal without such linkage and, indeed, could yield worse results with decentralized management pursuing its own objectives not necessarily related closely to student performance. In short, site-based management is not an end in itself but a means for implementing other reforms. Moreover, although the concept of decentralizing decisionmaking is appealing, there is little evidence to suggest that sufficient capacity exists in most schools to make it successful. As with many of the changes suggested here, implementation will require a period of learning and of attracting suitable personnel.

Programs "Known" to Be Successful

Frequently, it is asserted that we do, in fact, know what works. These assertions are often embedded in appeals for new resources because they provide examples of what would be possible with more funds. Some claims point to studies that indicate, for example, that a particular reading program or configuration of resources leads to improved student performance. Other examples, though, go beyond simple appeals for added resources. These include lists of quite convincing ideas such as "performance increases with the amount of time on specific tasks" or "subject matter knowledge by teachers is crucial to higher student performance." These assertions then lead explicitly or implicitly to notions that reproducing these programs or insisting on more time devoted to instruction provides an obvious path to higher student achievement.

When programs that are touted as "proven" to work are not adopted readily, the reason may not be their cost. Many programs described as important reforms require relatively modest expenditures, and some could be accomplished with existing resources. There are three other explanations for the failure of particular reform programs to be adopted. First, as observed earlier, there may not be very strong incentives to introduce such programs even if they are relatively inexpensive. They may be adopted because of idiosyncratic choices in some schools or districts, but nothing compels other districts to follow suit; and simply increasing knowledge about them is unlikely to lead to rapid diffusion. Second, such programs may compete with other programs and other objectives. In other words, they interfere or are perceived to interfere with existing incentives. Third, what is "known" might not be right. When there is limited experience with programs

that operate in particular environments with particular people, it is easy to confuse program effectiveness with other elements that make transfer of the program to other locations difficult or impossible. Without wider experimentation coupled with evaluation and learning , the list of programs "known" to be good may expand and contract without much relationship to the utility of any given program as a candidate for wider diffusion.

Ideas such as providing more time on core academic subjects or securing teachers with greater knowledge of the subject matter are indeed appealing. At the same time, it is hard to imagine legislating such measures into existence across schools. If their importance is known and if everybody in the schools is working to improve student achievement, we would expect such measures to be in place. When they are not, as is often the case, the prime reason is simply impotent incentives to place a premium on raising student achievement. Knowledge of what will enhance performance in specific circumstances is a minimal requirement for improvement. When such knowledge of what works is available, the need for changes in organization and incentives to ensure quicker and deeper penetration of worthwhile reforms becomes even more evident.

Disadvantaged Students

The educational problems of disadvantaged students are frequently treated differently from more general school reforms, but this is largely inappropriate. The most effective approaches to their education will be based on the same principles outlined here—careful attention to student outcomes, development and institution of performance incentives, evaluation of programs, and attention to both costs and benefits. For example, one of the most promising programs for disadvantaged students, the Accelerated Schools program, emphasizes clear objectives and regular student evaluation. Programs for disadvantaged students must, as with other programs, be driven by performance. Programs for such students may differ from programs for more advantaged students in the details—for example, by devoting more attention to early childhood education and parental involvement—but these elements, too, should be evaluated in the same manner as other school programs.

Goals 2000

The centerpieces of recent federal attention to schooling are the Goals 2000: Educate America Act, signed into law in March 1994, and the reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, which was signed into law in October 1994.19 This legislation, which follows from resolutions of the

nation's governors in 1989, has two important features. First, it makes clear that student performance is indeed a national problem that requires serious attention. Second, it begins to lay out consequential goals for students and schools.20 Both of these represent positive changes from the past.

One underlying assumption of Goals 2000, however, is that developing goals and education standards will itself set in motion steps to bring about their accomplishment. On this premise there is much more controversy.21 There is little evidence that the development of standards and the associated measurement of achievement by themselves will lead to noticeably improved student performance.

Nor is federal and state oversight of local reform plans a substitute for changing incentives. The most controversial goal, of developing opportunity-to-learn standards, or minimum levels of school inputs into the education process, has great appeal—how can we expect schools to meet more demanding academic standards without additional resources?—but also is very much at odds with the proposition that a great deal of inefficiency exists in the provision of schooling. It simply is not possible to specify a reasonable set of "required inputs" into the educational process.

The discussion here is fully consistent with the development of high standards for student performance and with the extension of these standards to better measurement of outcomes.22 The proposed method of achieving those goals, however, is distinctly different from the traditional approach of adding more resources to the existing incentive structure.

Implementing Change

As the current U.S. public school system does not emphasize student performance, it should not be surprising that performance does not meet our expectations. But, worse, the current structure is not on a path to improvement. Most new programs offer little in the way of incentives to improve student achievement and are accompanied by little experimentation and evaluation. Each of

these needs to be changed, but change also implies different roles for the participants in the system. The roles of principals and teachers and others are considered in Making Schools Work and receive special emphasis by the Committee for Economic Development (1994).

In many ways, teachers are the most important ingredient of our schooling system, and they must play an active part in the development of improved schools. The teachers who will be best able to work in a new system with enhanced decisionmaking autonomy are probably quite different from many current teachers in terms of experience, training, and aspirations, among other characteristics. Current teachers cannot, however, be ignored in the process. Even though there will be a significant turnover of teachers in the next decade, the current stock of teachers will remain a substantial portion of the total teaching force for many years to come. Implementation of new systems that involve very different responsibilities and rewards must consider transition policies, such as the use of two-tiered employment contracts. New teachers under a two-tiered contract would receive very different contracts from today's standard contract. They would involve altered tenure guarantees, more risks, and greater flexibility and rewards. Existing teachers, on the other hand, would continue under existing employment rules for tenure, pay, and work conditions unless they individually opt for the new teacher contract. Such a structure is one example of an approach designed to recognize the legitimate contractual arrangements with current teachers while establishing radically different structures for the future.

State governments also need to make substantial changes in the role they play in education. The new role of states is to promote and encourage experimentation and implementation of new incentive systems. The long-run future of school reform depends on developing new information, and the states have an essential position in this. They must first work to remove unproductive "input" regulations and certification standards, which unfortunately form the core of most current state education programs. To replace these, states need to work on establishing performance standards and explicit student outcome goals. An important part of this is encouraging experimentation with alternative incentive structures and technologies and providing direct support for the evaluation and dissemination of program information. Clearly, however, local districts do not currently have sufficient capacity to develop, implement, and evaluate their own systems. Moreover, rightly or wrongly, states often mistrust individual districts and undoubtedly will resist permitting complete flexibility within local districts. To deal with local malfeasance, when local systems fail to perform at acceptable levels, states should be prepared to intervene. The form of intervention is important, however. Perhaps the best response involves the assurance to individual students and parents that alternatives will be provided for nonperforming local districts, say through providing extensive choice or voucher opportunities. The opposite approach, pursued now, is either to develop extensive input and process regulations to reduce the range of potentially unacceptable actions by local dis-

tricts or to threaten to replace existing districts with state personnel. Neither provides the right incentives or any real assurance of improvement.

The role of states should evolve into a policy role and not a direct management role. As highlighted by the Committee for Economic Development (1994), states must retreat from tendencies to micromanage schools—something they cannot do effectively.

The federal government should take on a primary role in enabling standards to be developed, in supporting broad program evaluation, and in disseminating the results of evaluations. It should also be involved in supporting supplemental programs for disadvantaged and minority students. As mentioned, programs for the disadvantaged should follow the same guidelines as above but also may involve expansions of early childhood education, integrated health and nutrition programs, and other interventions to overcome background handicaps. Providing these added programs is the proper role for the federal government, which strives to ensure equality of opportunity for all citizens. The federal roles outlined here are largely consistent with current practice but are extended in directions to complement the performance emphasis proposed for schools.

Local school districts should take new responsibility for curriculum choices, managing personnel, including hiring and firing on a performance basis, and establishing closer links with businesses, particularly for the benefit of students not continuing on to colleges. While none of these departs radically from current roles, they would be significantly different in practice if states removed many of their restrictions on instruction and organization. Moreover, if major decisions devolved to local schools, new emphasis would be placed on management and leadership, and undoubtedly new capacity would have to be developed. Micro-management by school boards is similarly not the proper focus for their attention, but setting policy is.

Businesses also have new roles. While U.S. businesses have frequently lamented the quality of workers they receive from schools, they have never worked closely with schools to define the skills and abilities they seek in prospective workers. More direct involvement in schools, perhaps coupled with long-term hiring relationships, could help both schools and businesses. Moreover, if businesses insisted that employment candidates demonstrate high scholastic performance, students would have much greater incentives to work hard in school.23 Businesses could also be helpful in developing systems of performance incentives for school personnel while avoiding unintended adverse consequences.

There is every reason to believe that school performance can be improved. Students can do better, resources devoted to schools can be better used, and society can be better off. But optimism about the chances for improvement should not be confused with optimism that improvement will come quickly or

easily. Fundamental changes in perspective, organization, and day-to-day operations are required. There is tremendous enthusiasm and energy for improvement. They must be directed in productive ways.

But here our panel breaks with the tradition of calling for more funding. In fact, reform of schools will best be achieved by holding overall real expenditures constant. Schools must learn to consider trade-offs among programs and operations. They must learn to evaluate performance and eliminate programs that are not working. They must learn to seek out and expand upon incentive structures and organizational approaches that are productive. In short, they must be encouraged to make better use of existing resources. The basic concerns of economics, with its attention to the effectiveness of expenditures and to establishing appropriate incentives, must be used if schooling is to improve.

Marshall Smith observes in this volume that no one really thinks that money per se is important. What really matters is how it is spent. He is not surprised that schools as currently operated are inefficient. But surely the level of spending compared to the outcomes is important to taxpayers and should be important to policymakers. In education it has not been.

Economic discipline cannot be imposed blindly. It is recognized that variations in local circumstances, cases of special need, and start-up costs for new programs may require additional financing. But poor performance is certainly not, as it is often viewed today, an automatically convincing case for more money. Quite the contrary. In the long run, the nation may find it appropriate to increase school expenditures. It is simply hard to tell at this point. But it is clear that expanding resources first and looking for reform second is very unlikely to lead to an improved system—a more expensive system, certainly, but a system with better performance, unlikely.

References

Bishop, John. 1989. ''Is the test score decline responsible for the productivity growth decline?" American Economic Review 79(1):178–197.

Committee for Economic Development. 1994. Putting Learning First: Governing and Managing the Schools for High Achievement. New York: Committee for Economic Development.

Congressional Budget Office. 1986. Trends in Educational Achievement . Washington, D.C.: Congressional Budget Office.

Education Policy Committee. 1994. Looking Back, Thinking Ahead: American School Reform, 1993–1995. Indianapolis, Ind.: Educational Excellence Network, Hudson Institute.

Glass, Gene V., and Mary Lee Smith. 1979. "Meta-analysis of research on class size and achievement." Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 1(1):2–16.

Hanushek, Eric A. 1986. "The economics of schooling: production and efficiency in public schools." Journal of Economic Literature 24(3):1141–1177.

Hanushek, Eric A. 1989. "The impact of differential expenditures on school performance." Educational Researcher 18(4):45–51.

Hanushek, Eric A. 1992. "The trade-off between child quantity and quality." Journal of Political Economy 100(1):84–117.

Hanushek, Eric A. 1994a. "Money might matter somewhere: a response to Hedges, Laine, and Greenwald." Educational Researcher 23(4):5–8.

Hanushek, Eric A. 1994b. "School Resources and Student Performance." Paper prepared for the Brookings Institution conference, "Do School Resources Matter?"

Hanushek, Eric A. 1995. "Rationalizing school spending: efficiency, externalities, and equity, and their connection to rising costs." In Individual and Social Responsibility, Victor Fuchs, ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press/NBER.

Hanushek, Eric A., and Steven G. Rivkin. 1994. "Understanding the 20th Century Explosion in U.S. School Costs." Working Paper 388. Rochester Center for Economic Research, Rochester, N.Y.

Hanushek, Eric A., et al. 1994. Making Schools Work: Improving Performance and Controlling Costs. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Haveman, Robert H., and Barbara L. Wolfe. 1984. "Schooling and economic well-being: the role of nonmarket effects." Journal of Human Resources 19(3):377–407.

Hedges, Larry V., Richard D. Laine, and Rob Greenwald. 1994. "Does money matter? A meta-analysis of studies of the effects of differential school inputs on student outcomes." Educational Researcher 23(3):5–14.

Jorgenson, Dale W., and Barbara M. Fraumeni. 1992. "Investment in education and U.S. economic growth." Scandinavian Journal of Economics 94(Suppl.):51–70.

Kenny, Lawrence W. 1982. "Economies of scale in schooling." Economics of Education Review 2(1):1–24.

Kosters, Marvin H. 1991. "Wages and demographics." Pp. 1–32. In Workers and Their Wages, Marvin H. Kosters, ed. Washington, D.C.: AEI Press.

Linn, Robert L. 1994. "Evaluating the technical quality of proposed national examination systems." American Journal of Education 102(4):565–580.

Lucas, Robert E. 1988. "On the mechanics of economic development." Journal of Monetary Economics 22 (July):3–42.

Manno, Bruno V. 1995. "Educational outcomes do matter." Public Interest 119(Spring):19–27.

Marshall, Ray, and Marc Tucker. 1992. Thinking for a Living. New York: Basic Books.

McDonnell, Lorraine M. 1994. "Assessment policy as persuasion and regulation." American Journal of Education 102(4):394–420.

McKnight, Curtis C., F. J. Crosswhite, J. A. Dossey, E. Kifer, J. O. Swafford, Ken J. Travers, and T. J. Cooney. 1989. The Underachieving Curriculum: Assessing U.S. School Mathematics from an International Perspective. Champaign, Ill.: Stipes Publishing Co.

McMahon, Walter W. 1991. "Relative returns to human and physical capital in the U.S. and efficient investment strategies." Economics of Education Review 10(4):283–296.

Mosteller, Frederick. 1995. "The Tennessee study of class size in the early school grades." The Future of Children 5, no. 2 (Summer/Fall 1995):113–27.

Murnane, Richard J., and Richard R. Nelson. 1984. "Production and innovation when techniques are tacit: the case of education." Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 5:353–373.

Murphy, Kevin M., and Finis Welch. 1989. "Wage premiums for college graduates: recent growth and possible explanations." Educational Researcher 18(4):17–26.

National Commission on Excellence in Education. 1983. A nation at risk: the imperative for educational reform. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

National Research Council. 1989. Everybody Counts: A Report to the Nation on the Future of Mathematics Education. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Porter, Andrew C. 1994. "National standards and school improvement in the 1990s: issues and promise." American Journal of Education 102(4):421–449.

Ravitch, Diane. 1995. National Standards in American Education: A Citizen's Guide. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution.

Romer, Paul. 1990. "Endogenous technological change." Journal of Political Economy 99(5):S71–S102.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. 1994. The Condition of Education. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Wolfe, Barbara L., and Sam Zuvekas. 1994. "Nonmarket outcomes of schooling." PEER Background Paper. Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin. Discussion paper no. 1065–95.

Word, Elizabeth, John Johnston, Helen Pate Bain, B. DeWayne Fulton, Jayne Boyd Zaharies, Martha Nannette Lintz, Charles M. Achilles, John Folger, and Carolyn Breda. 1990. Student/Teacher Achievement Ratio (STAR), Tennessee's K-3 Class Size Study: Final Summary Report, 1985–1990. Nashville: Tennessee State Department of Education.