3

Evolving Health Care Scene

Overview

The nation's health care system is in a historic transformation driven by rising prices, pressures on public and private budgets, and scientific and technological change. These forces are prompting major changes in the structure, organization, financing, and delivery of health care. The health care delivery system today is not what it was yesterday, and not what it will be tomorrow. Hospitals are changing in ways not considered possible a few years ago. A combination of changes in payment policies and technological and scientific advances has permitted shifts from the traditional inpatient hospital setting to ambulatory care settings, the community, home, and nursing homes. Hospitals increasingly are offering nontraditional services including hospital-based ambulatory care, home health care, and skilled nursing services units (AHA, 1994a). Shortell and coauthors have aptly likened the turbulence in the health care system to ''an earthquake in its relative unpredictability, lack of a sense of control, and resulting anxiety. At the epicenter of this earthquake is the American hospital" (Shortell et al., 1995, p. 131).

The boundaries between hospitals and nursing facilities are beginning to blur, and the walls around them are moving outward into the community where community-based home health services and other alternatives to nursing facilities are developing (Shortell et al., 1995). The typical nursing home of the past provided primarily custodial care for the elderly needing assistance; persons with acute conditions were treated in hospitals. Today, the demand for nursing home care is shifting from the traditional custodial care model toward one that often has

a rehabilitative component (Johnson et al., Part II of this report1). Nursing facilities are beginning to provide a wide array of services to individuals who are disabled with an increasing number of unstable chronic conditions (Morrisey et al., 1988; Shaughnessey and Kramer, 1990). The type of care provided is also changing with the increasing severity of illness and disability of some of the residents; it includes rehabilitative care, ventilator assistance, care for residents with an emerging acute care crisis, and respite care. Special care beds in nursing facilities have expanded rapidly in recent years for patients with Alzheimer's disease or other dementia in general. Subacute care is offered in many nursing facilities for patients discharged from the hospital to the nursing facility (AHCA, 1995).

Impetus for Cost Containment

Enactment of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 began a period of tremendous growth in health care services, especially hospital services. The combination of (a) increased demand for services stimulated by increased public and private insurance and (b) reimbursement on a retrospective basis has stimulated a rapid rise in use, costs, and expenditures. The need for cost containment policies became evident as the cost of health care reached unprecedented levels and comprised a steadily increasing share of the nation's output.

In 1993, personal health care expenditures (PHCE) reached $783 billion. Although the rate of growth in very recent years is slower than it has been in more than three decades, spending for health care continues to increase faster than the overall economy. While the share of private funds shows a slight decline, public funds as a share of the total PHCE continued to increase, accounting for 43 percent of the PHCE in 1993. Medicare and Medicaid accounted for one-third of all PHCE (Levit et al., 1994). Moreover, the federal government's share of health care costs has been steadily increasing.

Growing concerns about the continuing increases in health spending led to the development of a series of cost containment measures beginning in the mid-1970s. These included the Certificate of Need program (1974–1986); stimulation of competition through support of health maintenance organizations (HMO) starting in 1974; and various constraints on reimbursement in the 1980s. A key step was the enactment of the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA) in 1982, which placed a cap on annual operating revenues per inpatient Medicare case at each hospital; it was followed in 1983 by Medicare's Prospective Payment System (PPS), under which hospitals are paid a predetermined amount per

|

1 |

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee commissioned this paper from Jean Johnson and colleagues. The committee appreciates their contributions. The full text of the paper can be found in Part II of this report. |

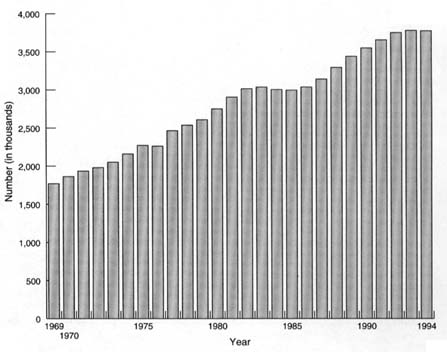

FIGURE 3.1 Employment in hospitals, United States, 1969–1994. NOTE: Monthly employment through October 1995 is higher than comparable employment for 1994.

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics Program.

Medicare discharge using national rates based on flat rates per admission calculated for each of the approximately 470 (in 1995) diagnosis-related groups (DRG).

Both of these measures have led to major changes in the financing and delivery of health care and have forced hospitals to change the way they staff their facilities and to integrate vertically (with payers) and horizontally (with each other) (ProPAC, 1995). In the years immediately following TEFRA and PPS, the use of inpatient services and hospital employment declined briefly. However, hospital staffing levels began to rise again in 1986 (see Figure 3.1).

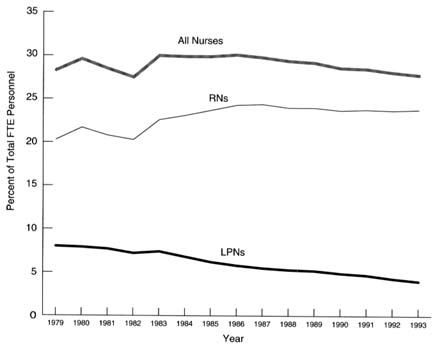

A possible explanation for the staffing increase is a combination of scientific and technological advances and an increasing proportion of hospitalized patients tending to be more critically ill requiring more intensive inpatient hospital care and skilled and specialty services, including nursing services (HRSA, 1993). This situation explains to some extent the continuing increases in registered nurse (RN) employment in hospitals even when other employment was declining (see Figure 3.2).

FIGURE 3.2 Nurses as a percent of total full-time-equivalent (FTE) personnel in community hospitals, United States, 1979–1993. NOTE: LPN = licensed practical nurse; RN = registered nurse. SOURCE: American Hospital Association, Annual Surveys, 1979–1993, special tabulations.

Managed care organizations2 such as HMOs and preferred provider organizations (PPO) developed rapidly, changing the nature of private health insurance and increasing price competition. These evolving payment systems have in turn affected the structure of the health care delivery system by limiting service and directing when and where patients receive their care.

Focus of the Chapter

This chapter presents a brief overview of the major changes occurring on the health care scene, with a focus on the hospital and nursing home sectors, and what these shifts mean for the organization and delivery of nursing services to

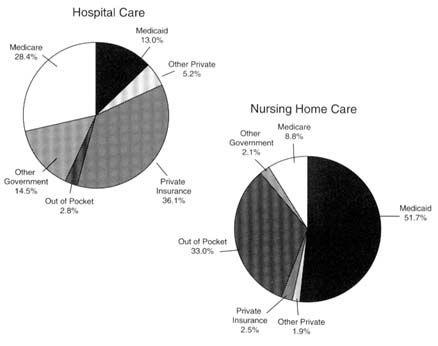

FIGURE 3.3 Sources of funds for medical care expenditures, United States, 1993. SOURCE: Levit et al., 1994.

patients.3 As stated in Chapter 1, hospitals and nursing homes represent two separate but related health care markets. Hospitals are a part of the basic acute health care system, and inpatient services are paid for largely by private insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid. The reimbursement for nursing home care, by contrast, is usually through Medicaid or out of pocket; almost no private insurance for long-term care is being purchased (see Figure 3.3). Also, hospitals historically have been not-for-profit institutions whereas nursing homes have been predominantly investor-owned companies. The committee believes that the issues resulting from the evolving health care environment that the nation is witnessing are related and yet different in many ways for the two sectors.

Private Insurance And Public Payers For Health Care

Health care in the United States is financed primarily through a combination of private health insurance and public coverage, and historically has been pro-

|

3 |

For a detailed discussion of the changing health care delivery environment and the evolution of managed care, see ProPAC (1994), Chapter 3; Shortell et al., 1995; Shortell and Hull, in press. |

vided through a fee-for-service (FFS) system. Although public efforts at reforming health insurance have not progressed, the private health insurance sector continues to experience rapid change as it responds to cost pressures from employers. This has led to greater competition in the market and shifts by employers and other purchasers of health care from some insurance companies to other companies, leading to some instabilities in the market. These shifts are reflected in major changes in the organization of the health industry including rapid consolidation into larger corporations through mergers; consolidations and integrated networks; diversification of products; corporate restructuring; and changes in ownership. The most important of the changes is the growth of managed care organizations.

Managed Care

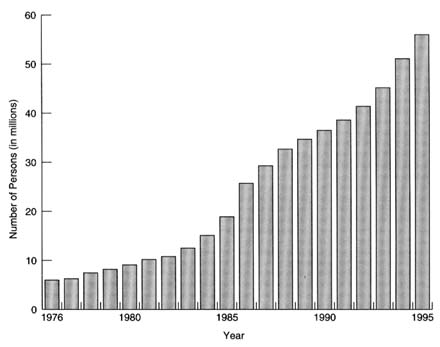

A combination of rising costs of care, dissatisfaction of payers, lackluster growth in personal income, and pressures on public and private budgets has led to the rapid growth of managed care. The emerging health care system is increasingly dominated by managed care organizations that are securing significant discounts from hospitals and physicians while attempting to reduce excess capacity and reduce the demand for high-cost services and procedures. Although HMOs have existed for half a century, their growth especially since 1980 has been phenomenal. The number of persons enrolled in HMOs has risen from about 6 million in 1970 to an estimated 50 million by the end of 1994 (see Figure 3.4). The 20 largest HMO companies have 59 percent of the total national enrollment. Nationally, the net increase in HMO enrollment rate from 1988 to 1993 was 38 percent; New England showed the highest regional level of penetration (26 percent). HMO penetration in Massachusetts reached 34 percent in 1993 and 40 percent by midyear 1994 (GHAA, 1995).

Compared to a typical FFS indemnity plan, HMOs reduce the use of health services. One Congressional Budget Office analysis (CBO, 1995) found that most of the reduction in use of health services is generated by group- or staff-model HMOs, which reduced services by nearly 20 percent. On average, independent practice associations (IPA) do little better than indemnity plans, reducing the use of services by about 1 percent. When these findings are combined using 1992 year-end enrollment patterns for HMOs and IPAs, the estimated average effect of HMOs is to decrease the use of health services by about 8 percent compared to indemnity plans. Approximately 37 percent of HMO enrollment was in group- or staff-model HMOs compared to 63 percent in IPAs and network plans at the end of 1992.

Although cost control has been the dominant force behind the rapid growth of managed care, in recent years the demand for value and accountability has emerged. Purchasers of health care, especially employers, have sought more

FIGURE 3.4 Number of people receiving care in HMOs, United States, 1976–1995. SOURCE: Adapted from GHAA, 1995, p. 3.

hard evidence on the quality, effectiveness, and appropriateness of the care they are buying (Shortell and Hull, in press).

A literature analysis of several peer-reviewed studies (Miller and Luft, 1994) found that in comparison to FFS indemnity plans, HMOs had generally lower hospital admission rates, shorter lengths of hospital stay, and fewer uses of hospital services. The studies also showed an average of 22 percent lower use of expensive procedures, tests, and treatments for which less costly alternative interventions were available. For most health conditions, HMOs appear to provide health care roughly comparable to that available through indemnity plans. Compared to FFS indemnity plans, HMO enrollees were less satisfied with service and patient–physician interaction, but more satisfied with the financing aspects of the plans. The authors found that the evidence comparing costs in HMOs and FFS indemnity plans was limited, with inconclusive results. Moreover, not much information is available on the impact of managed care on lowering overall health spending, and there is no persuasive evidence of lower growth rates for costs under managed care. The authors caution against generalizing across all managed care plans because of the rapid growth and diversity of plans in recent years. They express the urgency of additional research on managed care perfor-

mance on outcomes that goes beyond reducing costs, before the nation moves much further in this direction. At present almost no research has been conducted on whether the savings come from increased efficiency or reduced access and/or quality.

Davis and colleagues (1995) found that FFS enrollees were more satisfied with their plan's access and quality of care; managed care enrollees were more satisfied with their plan's cost, paperwork, and coverage of preventive care. The survey also found a high rate of involuntary plan changing, limited choice of physicians, and low levels of satisfaction among low income managed care enrollees. These findings are based on a population-based survey conducted by the Commonwealth Fund in 1994 of about 3,000 adults insured in FFS plans and managed care organizations.

Critics of managed care contend that the cost containment incentives of managed care may result in underservice and less than optimal care, especially for patients with chronic illness and those of lower socioeconomic status. Little evidence is available with which to evaluate the quality of primary care delivered by managed care plans or to show that the successes of managed care in relatively healthy populations can be replicated among sicker patients (Safran et al., 1994). To help fill that gap, the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS), a longitudinal study of patients' health care use and health outcomes was begun in the mid-1980s.4 Safran and colleagues found that relative to patients in an FFS plan, those in prepaid plans rated several aspects of an outpatient medical visit less favorably. The investigators compared the extent to which each of the five indicators of primary care quality (accessibility, continuity, comprehensiveness, coordination, and accountability) was rated over a 2-year period by a cohort of chronically ill patients in each of the three insurance plans—FFS indemnity plan, prepaid care through IPA, and group- or staff-model HMO. The investigators found that financial access was highest in prepaid plans; organizational access, continuity, and accountability were highest in the FFS plans; and coordination and comprehensiveness was lowest in HMOs. The authors conclude that these results raise questions regarding the associated cost inefficiencies and outcomes of care. It is an open question whether the magnitude of cost savings will continue after managed care has saturated the health care market.

On the other hand, Lurie and colleagues (1992) in their study of Medicaid patients in Minnesota found no difference in quality of care of chronically mentally ill patients between capitation plans and fee-for-service plans.

Ownership Structure

Several shifts are taking place in the ownership, control, and configuration of health care organizations. One shift is toward proprietary or investor-owned health organization chains (IOM, 1986a). Health organizations are often classified according to ownership because the corporate goals, tax status, and financing structures differ somewhat by ownership categories. Although nonprofit facilities generally have charitable goals, many facilities may seek to maximize revenues. Proprietary facilities generally are oriented to achieving profits, and an increasing number of these health organizations are publicly-traded corporations and multifacility organizations or chains.

The formation of not-for-profit independent hospitals predates that of investor-owned enterprises, although for-profit hospitals have been in existence for some time. For the past several years, a steady shift has been occurring from the traditional independent not-for-profit hospitals to for-profit consolidated enterprises and investor ownership, and not-for-profit hospitals have established for-profit subsidiaries and other arrangements (IOM, 1986a).

The largest proportion of new managed care organizations are proprietary; some traditionally nonprofit corporations are converting to proprietary status.

The majority of nursing facilities are proprietary, and facilities are increasingly owned by investors. Of the total nursing facilities in 1991, 71 percent were reported as proprietary, 24 percent were nonprofit, and 5 percent were government owned (NCHS, 1994). Nursing facilities, like other segments of the health industry, are consolidating into large health care organizations, with the largest chain reporting more than 90,000 beds in 1991.

Profit margins reported for the health care industry have generally been good (Burns, 1992; Abelson, 1993; Rudder, 1994). Forbes reported that in 1994, the all-industry median for return on equity was 12.6 percent for 1 year and 11.4 percent for 5 years (Kichen, 1995). The health care industry ranked first of 21 industry groups for its 5-year return on equity (HCIA and Arthur Andersen, 1994; Kichen, 1995).

Profit-making issues, however, are complex, and detailed discussion of the issues is beyond the scope of this study.5 The issues of profits on investment and excessive administrative and capital expenditures, however, need to be more fully understood. Few studies of the industry have been conducted, especially those that determine appropriate levels of expenditures for-profits, administrative costs, and capital.

Hospitals

As indicated earlier, technology, reimbursement policies, and continuing concern over rising health care costs have combined to stimulate competition in the health care industry. This competition in turn is prompting fundamental restructuring of the organization, financing, and delivery of health care in hospitals.

Hospital care expenditures accounted for 42 percent of personal health care expenditures in 1993. Growth in hospital spending decreased in 1993 for the third consecutive year, mostly because of reduced admissions and lengths of stay. As shown in Figure 3.3, nearly all hospital care is financed by third parties, with only 3 percent paid out-of-pocket. Private health insurance accounted for 36 percent; public funding financed 56 percent of the total PHCE, with the primary payers, Medicare and Medicaid, accounting for more than 41 percent share. Medicare's share of funding for all hospital expenditures was 28 percent in 1993, the highest since the mid-1980s. In 1993, 61 percent of Medicare benefits were for hospital care (including inpatient, outpatient, and hospital-based home health care), reaching $92.7 billion in 1993, an increase of 10.1 percent in just 1 year (Levit et al., 1994).

Hospitals are responding in various ways to the need to reduce costs and to adapt to managed care and other payment arrangements that fix in advance the reimbursements received for patient care. Among the responses are efforts to reengineer care and staffing for that care in innovative ways. These actions and their implications for hospitals and inpatient care are discussed briefly below.

Restructuring of Hospital Services

Integrated Systems

In response to the emerging dominance of payers, providers have engaged in various forms of reorganization and reevaluation. Searching self-examination is part of the current transition in the medical care arena. Physicians are organizing in some communities to negotiate with payers so that they can contract with other providers for the delivery of services to patients. Physicians in this role compete with traditional insurers—HMOs and other managed care organizations. Hospitals are organizing integrated delivery systems in which they purchase physician practices. Thus, hospitals are now competing with physicians and insurance companies in some markets.

Hospitals are developing integrated systems of care through networks, mergers, and consolidations. These structures seek to incorporate the concept of continuum of care, providing services ranging from ambulatory to long-term care in a "seamless" care system for the consumer. Hospitals also are competing for physician referrals and physician loyalty by teaming up with physicians in vari-

ous types of integrative arrangements. These include physician–hospital organizations, IPAs, and management service organizations. The growth of managed care has largely contributed to this trend toward the development of integrated systems.

The increased number of integrated service delivery networks is one of the more significant structural changes occurring today (ProPAC, 1995). Financing and delivery systems are combining into provider networks and managed care entities. Hospitals are joining together to form systems in which multiple hospitals are owned, leased, managed, or sponsored by a central organization. Between 1984 and 1990, the number of multihospital systems increased from 250 to 311, declining somewhat to 283 systems by 1993, probably as a result of mergers among systems (Shortell and Hull, in press). Groups of hospitals, physicians, other providers, insurers, and/or community agencies are also integrating to form more comprehensive delivery systems to market jointly a comprehensive set of services to plans, insurers, or purchasers in their communities.

These changes are having a major influence on what services are offered and where they are provided and, consequently, on hospital capacity and use. Vertically integrated entities are growing in importance, with increasing emphasis being placed on outpatient and community care in place of heavy inpatient orientation. About 11 percent of community hospitals reported in 1993 that they were already participating in health networks, working together with other hospitals, physicians, and insurers to coordinate a wide range of services for the community (AHA, 1994c). Many others reported working toward such collaborative formations.

Closures and Mergers

Hospitals are closing and entering into mergers and joint ventures at an unprecedented pace in order to strengthen their market share and realize economies of scale (ProPAC, 1995). Hospital closures reduce excess beds and lead to cost savings by allowing the remaining hospitals to spread their costs over a wider patient base. The American Hospital Association (AHA) reported closures of 675 community hospitals between 1980 and 1993.6 Thirty-four of the closures occurred in 1993 (AHA, 1994b). As might be expected, rural community hospitals have been particularly vulnerable to closures, outnumbering closures of urban hospitals, while representing slightly less than half of the total number of hospitals (Bogue et al., 1995).

Mergers involve the dissolution of one or more similar organizations and their assimilation by another. Mergers are undertaken either to eliminate direct acute care competitors or to expand acute care networks. They frequently convert inpatient capacity to other functions; only rarely does the acquired hospital continue acute care services after a merger (Bogue et al., 1995). Between 1980 and 1992, AHA reported 215 mergers involving 445 hospitals or health care systems (AHA, 1992).7 The AHA recorded another 18 completed mergers in 1993 (AHA, 1994c). More than 650 hospitals were involved in mergers or acquisitions in 1994, affecting more than 10 percent of the nation's hospitals. This number includes 219 investor-owned hospitals that were merged into other investor-owned chains and 154 investor-owned hospitals whose mergers into other chains were expected to be completed in 1995. In addition, 301 other hospitals were involved in 176 such arrangements during 1994 (Lutz, 1994).

As a result of closures, mergers, networking, and acquisitions, the number of independent community hospitals has been declining since the late 1970s. After declining rapidly between 1985 and 1990, the rate of decline during the 1990s has slowed. The number of community hospitals declined from 6,193 in 1970 to 5,829 in 1980, and 5261 in 1993. Between 1983 and 1993, admissions to these hospitals declined 15 percent, from 36 million to nearly 31 million (AHA, 1994a). The magnitude of decline varies by region, hospital size, and metropolitan status. (See Table 2.1 in Part II of the report.)

Mergers and integration of institutions, in the context of increasing restructuring of the delivery of health services, may provide an opportunity to rethink the way services are offered in many institutions and offer an approach to structural change. The possibility exists for avoiding duplication and reducing costs. For example, in addition to collapsing centralized services such as human resources, financing, and information services, clinical programs may be consolidated, potentially shifting nursing and other health personnel from their accustomed site of work.

Inpatient Activities

In the years immediately following the establishment of the PPS, noticeable reductions were observed in hospital inpatient admissions and inpatient days of care. Although this trend continued in the 1990s, the rate of the decline has slowed. Declining hospital admissions combined with shorter lengths of stay resulted in a 21 percent decline in inpatient days between 1983 and 1993 (AHA, 1994a). This drop, in turn, has led to a reduction in the number of beds staffed for use (see Table 3.1).

TABLE 3.1 Inpatient Activity in Community Hospitals, Total Patients and Patients 65 Years of Age or Older, United States, Selected Years, 1983–1993

|

|

Year |

||||

|

Inpatient Activity |

1983 |

1987 |

1990 |

1993 |

Percent Change 1983–1993 |

|

All patients |

|||||

|

|

Number (in millions) |

||||

|

Admissions |

36.152 |

36.601 |

31.181 |

30.748 |

-14.9 |

|

Beds |

1.020 |

0.955 |

0.928 |

0.916 |

-10.2 |

|

Inpatient Days |

273.200 |

227.000 |

226.000 |

215.900 |

-21.0 |

|

Length of Stay |

7.550 |

7.180 |

7.240 |

7.030 |

-6.9 |

|

Persons 65 years or older |

|||||

|

Discharges |

11.562 |

10.295 |

10.693 |

11.354 |

-1.8 |

|

Inpatient Days |

115.100 |

92.100 |

97.200 |

95.700 |

-16.9 |

|

Length of Stay |

9.960 |

8.950 |

9.090 |

8.430 |

-15.4 |

|

SOURCE: American Hospital Association, Annual Surveys, 1983–1993, special tabulations. |

|||||

For persons 65 years of age and older, however, after a decline of 5.4 percent in admissions and 18 percent in inpatient days between 1983 and 1986, inpatient hospital use has been increasing. The annual number of admissions for this age group grew by 7 percent between 1990 and 1993, whereas admissions for persons under 65 years of age declined by 5.5 percent (HRSA, 1993).

More recent data from the AHA indicate that inpatient admissions are increasing. A comparison of hospital data for the first quarter of 1995 and the first quarter of 1994 shows a 3.2 percent increase in total admissions. This rate of increase in admissions is the highest since 1976. The growth in admissions of persons 65 years and older accounts for a large part of this increase. While admissions show an increase, length of stay continues to decline, marked by a sharp decline of 7.8 percent among patients 65 years of age and older (AHA, 1995a). The drop in length of stay resulted in a decrease in inpatient days (see Table 3.2). Several factors in addition to cost containment influence inpatient length of stay, including reimbursement incentives, technological advances, and increased availability of home health care. The number of staffed beds in U.S. community hospitals has continued to decline since 1983. Between 1983 and 1993, the total number of staffed beds had dropped by more than 104,000 beds (AHA, 1995b (see Table 2.3 in Part II of this report). As seen in Table 3.2, this trend has continued in 1994 and 1995 (AHA, 1994c, 1995a).

Inpatient case mix also has changed in recent years, along with a strong trend toward higher levels of acuity (ProPAC, 1995). This increase in acuity can be attributed to several factors, including movement of less complex services out of

TABLE 3.2 Percent Change in Inpatient Community Hospital Utilization, United States, 1994–1995

|

Utilization |

Percent Change Quarter Ending March 1994–1995 |

|

Beds |

-1.5 |

|

Inpatient admissions |

3.2 |

|

Patients ≥ 65 years |

5.2 |

|

Adjusted admissions |

5.9 |

|

Inpatient days |

-2.6 |

|

Length of stay |

-6.5 |

|

SOURCE: American Hospital Association, National Hospital Panel Surveys, March Panel, 1994, 1995. |

|

the hospital or into outpatient services, and the pressures to reduce the length of stay stimulated by changes in reimbursement. The increased acuity of patients and the consequent complexity of inpatient hospital care and services require more specialized and intense nursing care than before. This is reflected in the increased use of special care units such as the intensive care units (ICU) in hospitals. The number of staffed beds in ICUs in community hospitals increased by 29 percent between 1983 and 1993. The percentage of total staffed beds that are ICU beds also rose during this period from 7.5 percent to nearly 11 percent in 1993. During the same period acute care beds dropped from nearly 82 percent to 64 percent (see Table 2.4 in Part II of this report).

Continuum of Care

Historically, the primary function of hospitals has been to treat acute illness and injury; prevention of disease and promotion of health have been the domain of the public health system and individual care givers. In the emerging health care system there are incentives to merge these two roles and to organize the entire continuum of care (Shortell et al., 1995). In an effort to maintain patient base as well as to capture market share, hospitals have extended the scope and type of services offered beyond the traditional acute inpatient services. They now emphasize prevention, health promotion, and primary care to a much greater degree than previously.

In responding to the need to reduce costs, hospitals have to some extent shifted the site of care and consequently some of the costs (Table 3.3). Changes in payment policies, incentives to treat patients in less costly sites, and technological advances have contributed to the shift for a growing number of services to

TABLE 3.3 Trends in Outpatient Visits and Other Selected Services Offered in Community Hospitals, United States, Selected Years, 1983–1993

|

|

Year |

|||

|

Total Number of hospitals offering: |

1983 |

1987 |

1990 |

1993 |

|

Home Health Care |

795 |

1,843 |

1,801 |

2,047 |

|

Hospice Program |

513 |

764 |

817 |

964 |

|

Skilled Nursing Facilities |

752 |

861 |

1,073 |

1,354 |

|

Outpatient visits (in millions) |

210.0 |

245.5 |

301.3 |

366.9 |

|

SOURCE: American Hospital Association, Annual Surveys, 1983–1993, special tabulations. |

||||

ambulatory care settings, to post-acute service settings such as skilled nursing facilities, or to home health care and rehabilitation services. This shift has resulted in substantial growth in the use of, and spending on, those areas. Hospital outpatient spending rose 290 percent between 1984 and 1993, while hospital inpatient expenditures went up only 82 percent (ProPAC, 1995). Spending for home health care also has grown rapidly. By 1993 expenditures for hospital-based home health care had reached about $4 billion (Levit et al., 1994).

Outpatient Care

While inpatient hospital use has been declining over the past decade, outpatient care, in terms of both the number of visits and the number of outpatient departments, has risen dramatically (Table 3.4). In 1993, approximately 88 percent of community hospitals reported having an outpatient department, compared to 54 percent in 1985. Furthermore, in 1993, community hospitals reported 367 million outpatient visits, an increase of about 5 percent from 1992 and 75 percent from the number reported in the early 1980s. The increase of outpatient surgeries accounts for much of the growth in outpatient visits. In 1993, more than half of all surgical procedures in community hospitals were performed on an outpatient basis, compared to 24 percent 10 years earlier (AHA, 1994a). Technological advances and cost-cutting efforts by payers have contributed to this growth.

Recently released data from the AHA National Hospital Panel Survey show a substantial increase in outpatient visits (AHA, 1995a). The percentage increase between 1994 and 1995 was 13 percent, the highest rate since 1970. (See Table 2.7 in Part II of this report.)

TABLE 3.4 Percent Change in Outpatient Community Hospital Utilization, United States, 1994–1995

|

Utilization |

Percent Change Quarter Ending March 1994–1995 |

|

Total visits |

13.0 |

|

Emergency visits |

6.5 |

|

Clinic visits |

16.5 |

|

Other visits |

14.0 |

|

SOURCE: American Hospital Association, National Hospital Panel Surveys, March Panel, 1994, 1995. |

|

In addition to the growth in outpatient services delivered on hospital premises, many hospitals are developing more hospital-based services to care for patients beyond the acute inpatient hospital care. They are also expanding their long-term care services. The principal factors prompting these changes include the growing numbers of elderly persons, children, and disabled adults requiring long-term, post-acute care; the shift away from long stays in the hospital; technological advances; and payer pressures to reduce hospital stays and to gain market share of the services.

Hospital-sponsored Home Health Services

The number of hospitals providing hospital-sponsored home health services increased from 29.7 percent in 1985 to 38.0 percent in 1992 and 42.2 percent in 1993 (AHA, 1994a). The growth in home health agencies was spurred by the inclusion of these benefits in Medicare. Home health services prior to that time were provided predominantly by public health departments and not-for-profit visiting nurse associations. Since that time, the growth of investor-owned chains and of hospital-sponsored or joint venture agencies has been substantial.

In recent years, the growth in the development of high-technology services such as ventilator care, enteral and parenteral nutrition, antibiotic therapy, and chemotherapy has also been rapid. Increasing use of these high-technology services in home health care has been stimulated by changes in hospital reimbursement.

Hospital-Based Skilled Nursing Units

Unoccupied hospital beds are being converted in some hospitals into post-acute skilled nursing units, hospice units, and special care centers. Patients are

''discharged" from the acute care inpatient hospital bed and admitted to the skilled nursing care or hospice unit or to their homes with provision of hospital-sponsored home health services.

Between 1983 and 1993 the number of hospitals reporting use of hospital-based skilled nursing services units more than doubled from 600 to 1,350. Areas with high AIDS caseloads have established special AIDS units. Other special care centers include cancer centers, transplant centers, designated high-level trauma centers, and neonatal intensive care units.

Nursing Homes

Although the nursing home sector of the U.S. health care system is not undergoing the rapid and intense turbulence occurring in the hospital sector, it is the recipient of seismic fallout from the epicenter of the earthquake (to continue Shortell's [1995] analogy). Fallout from the evolving patterns of reimbursement and delivery of care in hospitals, and other economic and demographic factors, are changing the characteristics of persons entering nursing homes and, therefore, the demand for nursing home beds. At the same time, persons needing primarily custodial care increasingly are looking for alternative long-term care settings. Hence, the sicker patients tend to concentrate in nursing homes. The increased acuity and disability of individuals needing long-term care are placing new types of demands on providers of care. This situation is exacerbated by the aging of the population.

The capacity of nursing homes to meet the increasing demand for services has been strained during the past decade. The demand for nursing home services and other long-term care services is growing with the increasing number of persons who are aged and chronically ill. The total number of licensed nursing facilities was about 16,600 in 1994 (AHCA, 1995). These nursing facilities had 1.67 million beds in 1994. Overall, the supply of beds in nursing facilities has not kept pace with the demand, especially in relation to the growth in the oldest-old population, those persons age 85 years and older (see Table 3.5). This demand will increase in the years ahead as the elderly represent an increasing proportion of the total population.

Occupancy measures the demand for nursing facility services and is often used as an indicator of an undersupply of beds. The occupancy rate in nursing facilities has remained high. The median occupancy rate nationwide was 93 percent in 1994. Wide variations are observed among states, from a high of 98 percent in Georgia, to 79 percent in Texas, to a low of 52 percent in Alaska (AHCA, 1995). Thus, some areas and states may have shortages of nursing home services and others may have an adequate or oversupply of nursing home beds (Swan and Harrington, 1986; Wallace, 1986; Harrington et al., 1992a, 1994a; Swan et al., 1993a; DuNah et al., 1995). In some states, such as Oregon, occupancy is down even when the supply is ratcheted down. Areas with shortages are

TABLE 3.5 Number of Licensed Nursing Home Beds per 1,000 Population Aged 85 and Older, by Region, Selected Years, United States, 1978–1993

|

|

Beds per 1,000 Persons 85 and Older |

|||||

|

Regions |

1978 |

1982 |

1986 |

1990 |

1993 |

Percent Change 1978–1993 |

|

Total U.S. |

610.3 |

559.5 |

537.0 |

520.3 |

479.7 |

-21.4 |

|

North central |

729.5 |

679.9 |

659.9 |

636.8 |

597.4 |

-18.1 |

|

Northeast |

516.8 |

477.7 |

475.5 |

470.3 |

453.6 |

-12.2 |

|

South |

594.5 |

552.9 |

520.7 |

504.2 |

455.1 |

-23.5 |

|

West |

571.7 |

488.9 |

454.8 |

436.5 |

383.6 |

-32.9 |

|

SOURCE: DuNah et al., 1995. |

||||||

of concern because they may limit access for those in need of services. This overall high occupancy rate reflects both the shortage of beds discussed above and the increase in patients discharged from hospitals needing subacute care and rehabilitative care (HCIA and Arthur Andersen, 1994).

The likely consequence of this shortage is that nursing facilities can be somewhat selective in their admission practices, and some have limited the access of individuals who may have the greatest need for services (Nyman, 1989a).

Forces Affecting Demand for Nursing Home Services

As the population ages and develops multiple chronic conditions, the need for long-term care (LTC) services, including nursing home care, will increase. The demand for nursing facilities to provide more complex services is growing in response to several trends, including increased age and disability of residents, medical technology, cost containment pressures, and government policies (Hing, 1989; Shaughnessy et al., 1990; Kanda and Mezey, 1991; Schultz et al., 1994).

The magnitude of the potential growth in demand is illustrated by the projected growth of the older population discussed in the previous chapter. Medical technology, formerly used only in the hospital, is being transferred to nursing facilities. The use of intravenous feedings and medication, ventilators, oxygen, special prosthetic equipment and devices, and other complex technologies has made nursing home care more difficult and challenging (Harrington and Estes, 1989; Shaughnessy et al., 1990). The kinds of services that are increasingly being provided in some nursing facilities are also creating a greater need for skilled nursing care, in particular, greater professional nursing involvement in the direct care of patients and in supervision, more clinical evaluation, and more financial and human resources.

Several federal government policy changes in the 1980s have contributed to

an increase in nursing home demand and government expenditures for nursing home services. As noted earlier in the chapter, the adoption of PPS led to early discharges from acute care hospitals and more referrals and admissions to nursing facilities (Guterman et al., 1988; Neu and Harrison, 1988; Latta and Keene, 1989; U.S. House of Representatives, 1990). Legislation in 1988 established a minimum level of asset and income protection for spouses when determining Medicaid nursing home eligibility, and this too contributed to an increase in Medicaid program costs (Letsch et al., 1992). These policy changes have all encouraged the demand for nursing home services and, thereby, increased Medicaid and Medicare outlays for this type of care.

Some states have also adopted policies to control Medicaid nursing home demand, including Medicaid eligibility policies and preadmission screening programs (Ellwood and Burwell, 1990; HCFA, 1992a,b; Harrington et al., 1994c). These policies may have had a constraining effect on demand and, consequently, on the growth of nursing home capacity.

Expenditures and Payments Policies

Expenditures for nursing home care reached about $70 billion in 1993 (Levit et al., 1994). As seen in Figure 3.1, unlike the hospital market, nursing home care is financed mainly by the government (63 percent in 1993) and out-of-pocket payments (33 percent in 1993). The Medicaid program paid 52 percent of the total bill in 1993; only 9 percent of nursing home care was financed by Medicare and 2 percent by private insurance.

Nearly 69 percent of the residents of nursing homes are recipients of Medicaid for at least some of their costs (AHCA, 1995). The limited role of private insurance and Medicare in paying for LTC distinguishes the long-term care market from the hospital market. Individuals who need nursing home care generally must pay for their own care out-of-pocket. The high cost of long-term care in nursing homes (about $30,000 to $50,000 per year) leads many individuals and families to spend down their resources, often to poverty levels. Those who exhaust their own resources before dying usually become eligible for Medicaid, which will then pay for their care over and above their complete social security and other retirement incomes.

Recent analysis by Spillman and Kemper (1995) shows that 44 percent of persons who use nursing homes after age 65 start as private payers, 27 start and end as Medicaid recipients, and 14 percent spend down assets to become eligible for Medicaid benefits. Of all persons 65 years of age, 17 percent can expect to spend some time using a nursing home and receiving Medicaid benefits; 3 in 5 of this group will have entered the nursing home already eligible for Medicaid.

As a consequence, a number of states have developed initiatives to reduce the strain on the state's budget. These efforts vary from state to state.

Cost Containment Policies

State Medicaid programs have undertaken a number of policy initiatives to control supply and reduce spending on nursing home care. This process began in the early 1980s, when federal budget cuts to state Medicaid programs became standard features of the budget process (Bishop, 1988).

Certificate of Need The most important policy affecting the supply of long-term care beds is the state's certificate-of-need (CON) program. The health planning and CON program established in 1974 (P.L. 94-641) gave states considerable authority and discretion to plan and control the capital expenditures for nursing facilities and other health facilities (Kosciesza, 1987). The effectiveness of CON policies in controlling bed supply has been widely debated (Cohodes, 1982; Friedman, 1982; Swan and Harrington, 1990; Mendelson and Arnold, 1993).

These controversies resulted in the repeal of the program in 1986. Even so, 44 states continued to use CON and/or moratorium policies to regulate the growth in nursing facilities in 1993 (Harrington et al., 1994a). Because of the cost pressures on states, we can expect most states to continue their efforts to limit the supply of nursing home beds even though their bed supply is not keeping pace with the aging of the population.

Medicaid Because Medicaid dominates the LTC market, Medicaid eligibility policies and reimbursement rates are of critical importance to both consumers and providers of nursing home care. The rapidly rising cost of care in a nursing facility, which is consuming an increasingly larger portion of the state Medicaid budget, has been a major concern to state policymakers. States have considerable discretion in developing Medicaid reimbursement methods and rates. Many states have undertaken initiatives to control the growth in nursing home reimbursement rates (Holahan and Cohen, 1987; Bishop, 1988; Nyman, 1988a; Holahan et al., 1993; Swan et al., 1993a,b).

Until 1980, states were required to pay for Medicaid nursing home services on the basis of "reasonable costs"; many states used retrospective reimbursement systems to pay the costs of care (GAO, 1986). The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1980 (OBRA 80) gave states greater flexibility in developing reimbursement systems. This provision, known as the Boren Amendment, allowed states to pay nursing facilities based upon what was "reasonable and adequate to meet the costs incurred by efficiently and economically operated nursing facilities in providing care."

Since 1980, there has been a pronounced shift away from retrospective reimbursement to prospective facility-specific methods (Swan et al., 1993a,b; 1994). In addition, the number of states with case-mix reimbursement has increased substantially (see Table 3.6). By 1996, about one-half of all state Medicaid

TABLE 3.6 Number of States by Medicaid Nursing Facility Reimbursement Method and by Number Using Case-Mix Reimbursement, United States, 1979 and 1993

|

|

Year |

|

|

|

1979 |

1993 |

|

Total number of statesa |

50 |

51 |

|

Reimbursement methodb |

||

|

Retrospective |

13 |

1 |

|

Prospective, facility-specific |

16 |

17 |

|

Prospective, class |

4 |

3 |

|

Prospective, combination |

17 |

30 |

|

States using case-mix reimbursement |

3 |

19 |

|

Average Medicaid per diem rate |

$28 |

$76 |

|

a The total number of states includes the District of Columbia. b The total number of states for 1979 does not add up to 50 states as Arizona did not have a Medicaid program in 1979. SOURCE: Swan et al., 1994. |

||

programs are expected to be using case-mix reimbursement. Medicaid nursing home reimbursement methods are primarily prospective and vary substantially across states. These methods create wide variations in rates and have dramatic impact on nursing home expenditures and staffing (described in chapter 6).

Medicare Medicare accounts for 9 percent of nursing home expenditures. Medicare retrospective payment methods based on reasonable costs have been widely criticized as inflationary (Schieber et al., 1986; Holahan and Sulvetta, 1989). Because prospective reimbursement systems have been shown to reduce costs in the hospital sector, the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) is considering this approach. Congress in OBRA 93 has mandated that Medicare study prospective reimbursement as a means of controlling nursing facility costs. In response, HCFA is conducting a demonstration project to study prospective case-mix reimbursement for Medicare and for participating state Medicaid programs.

The challenge is for Medicare to control its share of the costs while ensuring access, appropriate care for resource-intensive residents, and high quality of care (Holahan and Sulvetta, 1989; Weissert and Musliner, 1992a,b).

Alternative Sites of LTC Care

Federal Medicare policies have dramatically expanded coverage for alternatives to care in nursing facilities during the past 5 years. This expanded coverage encouraged the rapid growth in home health care agencies and in the volume of such services (Letsch et al., 1992; NAHC, 1993). Federal and state policies have also expanded alternatives to institutional care under the Medicaid home and community-based waiver programs (Justice, 1988; Lipson and Laudicina, 1991; Gurny et al., 1992; HCFA, 1992b; Miller, 1992; Folkemer, 1994). The net effect of all these programs is not clear; these types of programs may be reducing the demand for nursing facility care in some areas or the programs themselves may be growing as a response to the limited supply of nursing home beds in some areas.8

As seen in Table 3.7, growth in the nursing home industry is slower than that observed in alternative types of LTC facilities. The total number of licensed nursing facilities in 1993 was 16,959 (DuNah et al., 1995). These facilities had 1.74 million beds. While the growth in licensed nursing facilities has hovered around 2 percent per year for the past several years, and only 1 percent between 1992 and 1993, the increase in residential care facilities, including board and care, personal care, foster care, and/or assisted living facilities, has been rapid. In 1993, there were 39,080 licensed residential care facilities for the aged with about 642,600 beds (Harrington et al., 1994b). According to the National Health Provider Inventory, in 1991, there were nearly 13,170 board and care facilities with 120,636 beds for the mentally retarded (NCHS, 1994). These facilities do not have skilled nursing care and are not eligible for Medicaid and Medicare payments. During the period 1983–1993, the growth in residential care beds for the aged has been about 11 to 12 percent annually (Harrington et al., 1994c).

In 1993, home health care was provided to about 1.4 million persons per day by 7,000 home health agencies (NCHS, 1993a). Three-quarters of home health patients were 65 years of age and over, and almost 20 percent were 85 years and older. Two-thirds of home health patients were women. Among the home health patients in 1993, about one-half of the admission diagnoses were for the following six conditions: diseases of the heart and hypertension (17 percent); injury and poisoning (9 percent); diabetes (7 percent); and cerebrovascular diseases, malignant neoplasms, and respiratory diseases (6 percent each).

The number of licensed home health care agencies increased by 24 percent just between 1992 and 1993, and licensed adult day care agencies increased by 41

TABLE 3.7 Number of Licensed Long-Term Care Facilities, United States, 1992 and 1993

|

|

Year |

||

|

Type of Facility |

1992 |

1993 |

Percent Change 1992–1993 |

|

Nursing facilities |

16,800 |

16,959 |

0.9 |

|

Intermediate care facilities for the mentally retarded |

5,894 |

6,296 |

6.8 |

|

Residential care facilitiesa |

34,871 |

39,080 |

12.1 |

|

Home care agencies |

8,117 |

10,084 |

24.2 |

|

Adult day care agencies |

1,517 |

2,131 |

40.5 |

|

a Includes board and care, personal care, assisted living, and other categories of residential care for the aged that are licensed by states. Categories vary by state. SOURCE: Harrington et al., in press. |

|||

percent in the same period. This growth can be expected to continue, but the growth in this sector generally does not involve skilled nursing personnel. In 1993, expenditures for home health care reached nearly $21 billion, (not including the $4 billion spent for care provided by hospital based home health care). Public financing accounted for nearly one-half of the expenditures for home health care (Levit et al., 1994).

Restructuring of the Nursing Home Industry

Nursing facilities, like other sectors of the health industry, are consolidating into larger health care organizations. Although not as rapidly and widespread as the hospital industry, the nursing homes are diversifying in the services they offer. HCIA and Arthur Andersen (1994) report that 23 of the 25 largest nursing home chains were involved in acquisitions in 1993. Nursing homes and chains are also forming integrated networks of services with hospitals, physicians, subacute care providers, home health care, and other relevant providers. Despite the recent movement toward consolidation within the industry, nursing home chains control only about 35 percent of the market and the 20 largest chains operate only 18 percent of the nursing home industry (HCIA and Arthur Andersen, 1994).

Many providers are developing their own home- and community-based divisions or affiliating with existing providers of those services. Approximately 4 percent of nursing facilities were offering these services in 1992. Nursing facilities are also expanding to cover services such as specialty care, rehabilitation, adult day care, assisted living, and respite care. Approximately 22 percent of all nursing facilities currently offer assisted living services. Some nursing homes are shifting from being primarily a place for custodial care to being facilities with

residents receiving short-term rehabilitative care and other complex care requiring high technology such as ventilator-dependent patients discharged from the hospital who need subacute care skilled nursing services (AHCA, 1995).

Special Care Units

In the 1980s, special care units (SCU) emerged as an important intervention for care of persons with special needs, ranging from care requiring high technology to care for dementia. Increasing numbers of nursing facilities are shifting from traditional custodial long-term care to a more specialized level of care (AHCA, 1995). Today more than 1 in 10 nursing facilities have a special unit or program for people with dementia, with more than 1,500 SCUs.

By 1994, nearly 90,000 beds were dedicated to special care. Most of these beds are dedicated to residents with Alzheimer's disease or those needing special rehabilitation services. The most dramatic increase has been in ventilator care beds, from 3,162 in 1993 to 13,291 in 1994. Beds dedicated to special rehabilitative patients increased by 2000 and beds dedicated to AIDS patients grew by 2,300 between 1993 and 1994. Although there is much diversity among SCUs, most incorporate some type of physical modification, including security measures to limit egress, specialized activity programming for residents, and special training for staff, who are often permanently assigned to the unit. These units do not focus only on older adults in the later stages of life, but their development is fueled by Medicare's hospital PPS and other payers of health care (Lyles, 1986; Ganroth, 1988; Swan et al., 1990; AHCA, 1995).

Subacute Care Units

Nursing homes are also expanding to cover subacute care. Subacute care is increasingly becoming acceptable as an alternative to cost-effective health care delivery model. Subacute care units of nursing facilities are emerging in response to the need to provide care to patients who suffer from medical conditions or are recovering from surgical procedures and require a broad range of medical and rehabilitative services. More than 50 percent of nursing home admissions today come from hospitals, and most patients need care for unstable medical conditions. The subacute care option is favored by payers because nursing facilities generally can provide such care at lower cost than hospitals. Many subacute care programs are clinically and therapeutically comparable to the medical, surgical, and rehabilitation units of an acute care hospital, yet the cost of care in a subacute care unit is about 40 to 60 percent less than comparable care in an acute care setting. The higher reimbursement rate for subacute care is also attractive to nursing facilities. Although hospitals are ahead of nursing facilities in establishing subacute care units, several major nursing home chains are rapidly moving into this area. At the present time, more than 10 percent of nursing facilities offer

some type of subacute care. Many more skilled nursing facilities and hospital-based skilled nursing units are developing and implementing subacute care programs. Today, more than 15,000 beds are dedicated for subacute care. Growth in subacute care is projected from $1 billion today to $10 billion by year 2000. (Stahl, 1995b).

Rules related to quality assessment and quality improvement, personnel requirements, and admissions practices have been set forth by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), which has recently incorporated subacute care into its survey process. Outcomes, physical plant, and physician credentials are three major areas addressed in JCAHO Accreditation Standards for Subacute Units (Stahl, 1995a).

Implications For Nursing Services

The above narration is a brief overview of the rapid and perhaps fundamental changes occurring in the health care system and the movement toward a continuum of care. Redesign and reengineering have become principal strategies of the 1990s for many health care organizations. Institutional care—hospitals and nursing homes—and the personnel who provide the care are particularly affected.

Although the issues affecting the nursing home industry are somewhat different in kind and intensity from those in hospitals, they have not escaped the effects of the health care transition. Under sustained cost pressures, most states are expected to continue their efforts to limit the supply of nursing home beds, even though the bed supply in many states may not be keeping pace with the aging population. The challenge is to match staffing levels and skills to the changing characteristics of the residents.

The focus of care is shifting. The emphasis is no longer on inpatient hospital care; rather, hospitalization is viewed as one event in a patient-based continuum of care. Health care providers, physicians, and nursing staff are increasingly called upon to change the way they deliver patient care. The model has changed to care delivered across a continuum, not focused on a particular episode of hospitalization, through the use of teams, case managers, and protocols. All these efforts have led to changes in the nursing delivery patterns developed mostly over the last two decades for organizing the delivery of nursing care in hospitals. Such a major transformation of the health care environment cannot be accomplished successfully without support of the nursing professions and without changes in management and governance structures (Shortell et al., 1995; VHA, 1995).

Changes that affect any single part of the health care sector will have implications for the work of nursing personnel and the outcomes expected from their respective contributions. Clearly, given that there are more than 3 million nursing personnel, the number of interactions they have with others in the system is potentially limitless and, therefore, of great relevance.

The transformation of hospitals, nursing homes, and other health care orga-

nizations will continue to grow as organizations expand their search for solutions to issues brought about by reform and change in an environment that is increasingly drawn toward delivery of less costly and noninstitutional care. Just as the hospital of the future will serve only very sick patients requiring highly complex care, the nursing home of tomorrow will also serve patients with serious disabilities and with rehabilitative and other subacute care needs. The rest of the population will increasingly receive care in outpatient units, home- and community-based settings, assisted living facilities, and similar settings.