Nursing Injury, Stress, and Nursing Care

Bonnie Rogers, Dr.P.H., C.O.H.N., F.A.A.N.

The health care industry is one of the largest employers in the United States, with more than 7 million employees in 1990 and with that number expected to increase to more than 10 million by the year 2000 (BLS, 1991). These health care environments are high-risk workplaces with a wide range of exposures and hazards (see Table 1) (Hudson, 1990; Rogers and Travers, 1991; Wilkinson et al., 1992). The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports the incidence rate per 100 full-time workers for nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses for 1993 was 11.8 for hospital establishments and 17.3 for nursing and personal care facilities. This compares to a private industry rate of 8.5 (BLS, 1994b). In addition, the Bureau reports that for 1992 the incidence of injuries and illnesses involving days away from work is greater for certain occupations than their proportion of total employment. These relatively hazardous occupations include male-dominated work, such as construction and transportation; female-dominated activities, such as nursing care and housekeeping services; and gender-shared activities, such as assembling products. Nurses' aides (NA) were second only to truck drivers in the total number of cases of disabling injury and illness, with an estimated 145,900 cases for truck drivers compared to 111,100 for NAs. For persons in all occupations working less than 1 year, NAs were reported as having the most injuries or illnesses (approximately 67,000), primarily sprains

Dr. Rogers is an associate professor of nursing and public health and director of the Occupational Health Nursing Program, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

TABLE 1 Categories of Potential or Actual Occupational Hazards |

|

Biologic-infectious hazards: Infectious-biologic agents, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, that may be transmitted via contact with infected patients or contaminated body secretions or fluids. Chemical hazards: Various forms of chemicals that are potentially toxic or irritating to body systems, including medications, solutions, and gases. Environmental-mechanical hazards: Factors encountered in work environments that cause or potentiate accidents, injuries, strain, or discomfort (e.g., poor equipment or lifting devices, slippery floors). Physical hazards: Agents within work environments, such as radiation, electricity, extreme temperatures, and noise, that can cause tissue trauma. Psychosocial hazards: Factors and situations encountered or associated with the job or work environment that create or potentiate stress, emotional strain, and interpersonal problems. |

and strains, and they cited overexertion related to patient care as the primary cause.

The cost implications to health care providers of relatively high injury rates for their employees are especially troublesome down the road because, according to BLS estimates, the industry's work force is expected to grow at twice the rate for all nonfarm wage and salary workers between 1992 and 2005. In 1992, private sector health services employed 8.5 million workers, for whom nearly 700,000 work-related injuries and illnesses were reported that year.

Nursing personnel deliver care to individuals in a variety of settings including hospital-based and community-based environments. Only within recent years has any real attention been paid to the occupational risks and injuries of nurses. Also, there is evidence that stress related to work overload and staffing patterns, including shift work, can and does contribute to illness and injury in the nurse population (Jung, 1986; Phillips and Brown, 1992). Many factors such as the physical work environment, organizational and institutional characteristics, and personal work practice habits contribute to health care workers' occupational risk for hazard exposure and the resultant injury and stress that occurs (Rogers and Travers, 1991). The impact of these events is of concern not only in terms of the health risk to the worker, but also because of the effects on quality care and nursing.

In this paper, much of the research that is discussed describes the nature and severity of specific injuries of major concern in nursing and stress in nursing. The paper also provides some linkage, although less frequently, for the relationships of injury and stress to the quality of nursing care delivered and the impact of these factors on the nursing profession. Several investigations have reported

various types of injuries, but back injuries and needlestick injuries are of most concern and therefore will be most examined. While the reporting of assaults on health care workers may be improved, violence toward this group seems to be rising and will be discussed as a serious emerging threat (Lanza, 1992; Lechky, 1994). In addition, stress continues to plague nurses resulting in burnout and high turnover. It is clear that factors influencing injury and stress, and interactions between and among them, are of significant importance.

Injuries in Nursing Practice

Back Injuries

Although back injuries are considered the most expensive workers' compensation problem today (McAbee, 1988), the extent of low back pain and injury in nursing personnel is thought to be underestimated. A survey by Owen (1989) of 503 nurses found that only 34 percent of respondents with work-related low back pain filed an injury report, and 12 percent were contemplating leaving the profession because of the problem. Several studies indicate that tertiary care hospital staff have reported work-related back pain and injury and that they implicate lifting techniques, poor staffing, ergonomics, inadequate communication, and constitutional factors as contributory factors. Recommended approaches to reduce the incidence of occupational back injury include better mechanical lifting devices, improved staffing, improved training and education, and attention to worker-job capabilities. (Harber et al., 1985; Marchette and Marchette, 1985; Arad and Ryan, 1986; Jensen, 1987; Carney, 1993; Jorgensen et al., 1994).

Wilkinson and colleagues (1992) retrospectively investigated occupational injuries among 9,668 university health science center and hospital employees during a 32-month period. During this time, 1,513 injuries were reported with the most frequent being needlestick injuries (32.1 percent) followed by sprains and strains (17.2 percent); of the latter, 55 percent involved back injuries that were reportedly caused by lifting and twisting motions. Nearly 10 percent of those injured lost time from work. Out of 18 job classifications analyzed, nursing, which included NAs, ranked third highest in injury reports. In overall reporting, professional nurses reported the highest number of illnesses and injuries; within the total nursing group, however, NAs reported the highest injury attack rate after data were adjusted for the size of the population at risk. Workers' compensation costs were highest for back injuries, which equaled $171,957. Other types of injuries reported included lacerations and contusions.

Through survey and ergonomic analysis, including videotaping in a Wisconsin nursing home/long-term-care facility, Owen and Garg (1991) evaluated 38 nursing assistants with respect to factors associated with back injury. Tasks were categorized into 16 areas, and activities associated with transferring clients from

one location to another (e.g., transfer from toilet to chair; bed to chair; tub to chair) were ranked highest (the top 6 out of the 16 categories).

In a related article, Garg and colleagues (1992) observed nursing assistants who worked in teams of 2 and performed 24 patient transfers per 8 hour shift by manually lifting and carrying patients. Assistive devices (e.g., hydraulic lift) were used less than 2 percent of the time. Patient safety and comfort, lack of accessibility, physical stresses associated with the devices, lack of skill, increased transfer time, and lack of staffing were some of the reasons cited for not using these assistive devices. The 2-person walking belt manual method for transferring was perceived to be the most comfortable, secure, and least stressful approach. Adequate numbers of effectively trained personnel, however, are needed to carry out this approach. In addition, environmental barriers (such as confined workplaces, an uneven floor surface, lack of adjustability of beds, stationary railings around the toilet) made the job more difficult. Nursing assistants had a high prevalence of low-back pain and 51 percent of nursing assistants reported visiting a health care provider in the past 3 years for work-related low-back pain.

Kaiser-Permanente Medical Centers in Portland, Oregon, found back injury rates from workers' compensation claims ranging from 10 percent to 30 percent on hospital units. As a result, a back injury prevention project was pilot tested (Feldstein et al., 1993). Divided into intervention and control groups, 55 nurses, NAs, and orderlies participated in the project. Instructional methods on body mechanics, transfer maneuvers, exercise, and stretching were provided to the intervention group. Prior to the intervention, information specific to back pain and injury was collected, resulting in the following data: 86 percent reported work-related back fatigue; 74 percent reported that back pain interfered with the quality of work performance; 55 percent reported lost work time; 32 percent reported lost time of more than 3 days related to the injury; 60 percent required medical intervention; and 91 percent reported that patient handling put them at risk. ''New" nurses with less than 5 years of experience reported more frequent back pain, but veteran nurses considered their injuries more disabling. Body mass index and lack of flexibility were significantly associated with back pain and injury, while educational levels were inversely related. Age, height, weight, and job title showed no association. Although not statistically significant, scores used to measure back pain and fatigue were reduced after the intervention while no such reduction was seen in the control group. The intervention group had a 19 percent improvement in their average total score for the quality of patient transfers, a 17 percent improvement in preparation for transfer, a 15 percent improvement in the position for transfer, and a 26 percent improvement in the actual transfer. The control group did not show any significant improvement during the same time period. The study findings suggest that if new nurses are truly at higher risk, the need for aggressive new employee training is needed.

In a British study of work-related back pain, Newman and Callaghan (1993) analyzed data from 173 nurses and midwifery staff (the response rate was 65

percent). Of those responding, 76 percent had experienced pain in the past 2 years and 50 percent either took time off work or needed to recuperate on days off. The total number of days nurses were "unfit" to work totaled 2,769 or 2.63 days per nurse per year. An estimated cost for lost work time equaled $146,622. Only 6 percent of nurses indicated that they reported every back pain injury they suffered. Perceived risk factors for back injury included inadequate staffing and staffing patterns, heavy dependent patients, previous back injury, lack of equipment, working in confined spaces, and the type of uniform worn (the dress-type uniform created lifting and motion problems).

Based on a survey of 100 nurses who reported work-related back injuries and comparison with a control group of uninjured nurses, Garrett and colleagues (1992) found that nurses in the early phases of assignment on long-term-care units were at greatest risk of back injury. In addition, severity of injury was significantly related to the evening tour of duty and the weight of the nurse (greater than 200 pounds), with the latter always leading to lost work time. Forty percent of nurses in this category were ultimately disabled. Approximately three-fourths of the reported back injuries resulted in lost duty or light duty assignments compared to only 11 percent for other injuries reported. No differences were found among genders or nurse job classifications (registered nurse, licensed practical nurse, nurse assistant). The findings in this study related to lack of or limited work experience are consistent with those of McAbee (1988) who reported that 72.3 percent of study subjects with less than 3 years of experience suffered back injuries.

Cato and colleagues (1989) surveyed 53 orthopedic staff nurses in a large hospital regarding the incidence and severity of back pain and injury. Nearly two-thirds of respondents reported work-related back pain, with 90 percent indicating that patient handling was responsible for their most severe pain episode. While assistive devices were considered to be adequate, staffing levels were cited frequently as inadequate for lifting assistance. Better staffing and staff availability, improved body mechanics, and assistance with transfers were identified as the most helpful risk reduction strategies.

Several related studies have linked nurse-to-patient ratios and the incidence of back pain or injury. Larese and Fiorito (1994) compared musculoskeletal disorders in nurses working on general hospital (GH) and oncology department (OD) units. For nurses working on the GH unit, 48 percent reported work-related back pain and 19 percent had lost work time, compared to 33 percent and 9 percent of the OD nurses, respectively. The most important factor associated with back pain and injury was the nurse-to-patient ratio for assisting patients. The authors reported that an analysis of working conditions revealed that both groups of nurses were subject to frequent and heavy lifting, lowering, pushing-pulling, and so on. The nurse-to-patient ratio for GH nurses, however, was 0.57 nurses for every 1 patient, compared to 1.27 for OD unit nurses. A better ratio

between nurses and patients and work distribution, as well as specific ergonomic training, was recommended.

Rodgers (1985) reports that in a study of 95 back-injured nurses, many nurses were forced to lift alone when assistance was not immediately available. Nurses reportedly felt pressure to complete the task even though they knew the procedure was dangerous. The author indicated that management must be more responsive to establishing better staffing levels that could assist in the prevention of both the initial injury and reinjury to the back.

Greenwood (1986) completed a retrospective study of 4,000 back injury reports of hospital employees, including dietary staff, housekeepers, registered nurses (RN), licensed practical nurses (LPN), and NAs. Forty percent of the back injury cases were represented by NAs. Influencing factors included employment for less than 1 year and long working hours. Nearly 40 percent of the cases resulted in lost work time. In another report, Venning and colleagues (1987) surveyed and observed RNs, NAs, and orderlies and found several factors as significant predictors: jobs with patient lifting; frequency of lifting; job category (i.e., NAs and orderlies were nearly twice as likely to sustain an injury); and history of previous back injury.

Because of a high proportion of workers' compensation claims among hospital medical center employees (twice the rate of all state employees), Neuberger and colleagues (1988) conducted a descriptive study to investigate occupational injuries in this population. An analysis of workers' compensation claims for the 1-year period indicated that 855 injury events were reported, resulting in 4,825 lost work days and $326,886 in medical care and disability claims costs. The overall annual reporting rate was nearly 20 per 100 full-time-equivalent workers and occurred more often in women employees under 30 years of age. In fact, the rate in younger employees was 77 percent higher than in older employees. Those with repeat injuries had nearly twice as many lost work days and accounted for nearly one-fifth of those injured, one-third of the reported incidents, and one-half of the claims costs.

The Royal College of Nursing in Great Britain estimates that as many as 3,600 nurses leave the profession each year as a result of back injury, which incurs a replacement cost of approximately $90 million and more than $100 million in health care costs. In addition, other national findings suggest that a high proportion of back injuries in nurses and nursing assistants go unreported, that mechanical aides are inadequate, that reports are not investigated, and that back injuries may be thought of as acceptable risks (Nursing Times, 1992).

Evidence is clear that back pain and injury are a major problem in nursing, and they affect all practitioners who handle patients. The effect of these injuries can be measured in worker pain and suffering, disability, lost work time, absenteeism, medical care costs, personnel replacement costs, decreased productivity, and anger and confusion. Several authors implicate poor staffing, working conditions, and equipment design as factors contributing to decreased productivity,

fatigue, and absenteeism, which then affect the quality of nursing care delivered and available. Clearly, more research is needed to validate these propositions.

Needlestick Injuries and Exposure Risk

A new era of concern about occupational hazards for health care workers began in 1984 when the first case of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmitted by needlestick injury was reported in The Lancet (Jagger, 1994a). This has heightened the awareness in the health care community that numerous biological agents may be transmitted via needlestick and that exposure to blood-borne pathogens, including hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV and HCV) and other potentially infectious materials, need to be considered a major threat (CDC, 1992; Editorial, 1993). Marcus and colleagues (1991) report that needlestick exposure to HBV carries a 30 percent risk of infection while HIV needlestick contact carries less than a 1 percent chance of seroconversion. In a more recent review of the literature on HBV, HIV, and HCV exposure, however, Gerberding (1995) reports that the risk of transmission of HBV and HIV after needlestick injury seems to be related to the level of viral titer in the contaminant and, for HBV, correlates with the presence or absence of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg). The author reports on estimates of HBV infectivity ranging from 2 percent (HBeAg absent) to 40 percent (HBeAg present) and ranging for HIV from 0.2 to 0.5 percent. Estimates for HCV transmission are not well documented, but range from 3 to 10 percent. Although studies have indicated that the risk of HIV transmission is substantially lower than that for HBV, the fear of HIV acquisition is greater (Becker et al., 1989; Moore and Kaczmarek, 1990).

Occupational exposure may occur from a needlestick injury or other "sharps" injury, or from mucous membrane contact with contaminated blood or body fluid. Needlestick injury is the principal exposure route accounting for 80 percent of the occupational HIV exposure (Marcus et al., 1991). Numerous studies have found that nurses are the primary target of needlestick injuries (McEvoy et al., 1987; Wilkinson, 1987; Henderson et al., 1990; Marcus et al., 1991; Doan-Johnson, 1992). Several studies have reported incidence rates for needlestick injuries ranging from 10 percent to 34 percent (Jackson et al., 1986; Willy et al., 1990; Linnemann et al., 1991). These figures may be seriously underestimated, however, as studies also indicate estimates ranging from 30 percent to 60 percent for nurses' failure to report needlestick incidents (Hamory, 1983; Jackson et al., 1986; AHC, 1990; Moorhouse et al., 1994).

Work practice behaviors may lend themselves to increased risk of injury. Results of a national survey of certified nurse midwives indicated that 36 percent of respondents reported breaking needles and 63 percent (453 of 721) continued to cap needles (Willy et al., 1990), even though evidence is clear that recapping is the cause of one-third of all needlestick injuries (Jagger et al., 1988). Another study of 4 Michigan hospitals found, upon inspection of sharps disposal contain-

ers, that up to 60 percent of needles were capped (Becker et al., 1990). The effectiveness of work practice controls is of concern and the use of engineering controls would be more effective (Kopfer and McGovern, 1993).

English (1992) reported findings of a study on needlestick injuries conducted for a 1-month period in 17 hospitals in Washington, D.C. Of the 72 injuries reported, 46 percent were from RNs and recapping was most associated with needlestick injuries (14 percent). Eighteen injuries (25 percent) were to "downstream" housekeepers and aides who did not use such devices in their practice. Mallon and colleagues (1992) reported similar findings in a study of 332 reports of occupational blood and body fluid exposure. During a 9-month period needlestick and other sharps injuries accounted for 83.4 percent of all reports. In addition, failure to use universal precautions was cited in 34 percent of the reports.

Much of the concern related to needlestick injuries is related to the possible consequences of contracting AIDS. As of December, 1991, in the United States alone, 218,301 persons had been diagnosed with AIDS. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that this figure may be 50 percent lower than the actual figure, due to inadequate diagnoses and non-diagnosis due to individual fear of positive test results. In addition, as of December 1993 the CDC has identified 123 documented or possible cases of occupationally acquired HIV (CDC, 1994), which represents two-thirds of the 176 documented cases worldwide (Jagger et al., 1994). Nurses and clinical laboratory workers, primarily phlebotomists, ranked first among HIV infected workers, with each group accounting for 24 percent of the 123 cases.

Jagger (1994b) reports surveillance data on percutaneous injuries for a 1-year period (1992–1993) from 58 participating hospitals. Of all the cases reported (n = 471), nurses and phlebotomists each accounted for 157 and 150 injuries (33.3 percent and 31.8 percent) respectively, with two-thirds of the injuries occurring in patient rooms (53.3 percent) and in the emergency department (14.0 percent). Recapping needles has been identified as a continual source of worker exposure (Ribner et al., 1987), and many of these injuries are considered to be preventable through use of safer devices, procedures, and work practices. In another study by Neuberger and colleagues (1988) of RNs and LPNs, needlestick injuries were the most frequently reported (69 percent and 50 percent respectively) and lifting injuries accounted for the most lost work time. Neuberger compared the needlestick injury findings to an earlier study of needlestick injuries (Neuberger et al., 1984) in the same population and found significant reductions (74 percent) in needlestick injury rates. Neuberger contributes these reductions to improved staffing and equipment and to employee education.

Several studies have found that nurses and other health care workers have expressed fear of contagion for self and family members with respect to caring for AIDS patients (Barrick, 1988; Baer and Longo, 1989; Boland, 1990). Based on a statewide survey of 243 Florida hospital nurse administrators, Nagelkerk

(1994) discusses in detail the impact of AIDS on recruitment and retention in hospitals, and notes that AIDS patient care is resource and manpower intensive and that nurses have a significant fear of exposure. For example, the author states:

Not only did nurse administrators report that their staff feared caring for those with AIDS, but patients also had fears and requested room or unit transfers. Many administrators resorted to assigning private rooms for AIDS patients. The nurses feared contagion and death. One nurse administrator wrote, "It's not like other communicable diseases; AIDS carries a death sentence." While there was empathy for nurses' concerns and fears, most reported setting one firm rule: Nobody refuses care for assigned patients regardless of diagnoses. Many reported confrontations with individual nurses, which ultimately ended in voluntary resignation, dismissal, or the nurse's agreement to care for the assigned AIDS patient. After one incident, the informal network or grapevine worked well and others did not openly challenge the rule (p. 32).

Nurse administrators also reported several findings:

- staff were frequently physically and mentally exhausted;

- universal precautions were seen as cumbersome and time-consuming and often were not used;

- staff nurses distanced themselves from patients, providing care quickly and limiting interactions (seen as both an emotionally protective and an exposure control measure).

In addition, nurse administrators feared shortages in qualified personnel caring for AIDS patients, as some staff nurses indicated they would not personally work on an AIDS unit and that they might get out of nursing altogether.

In a somewhat contrasting study, van Servellen and Leake (1994) conducted a convenience sample survey of 153 hospital nurses from 7 California-based hospitals who provided nursing care to AIDS patients. While nurses reported some degree of emotional exhaustion and somatic complaints, no significant associations were found between emotional distress and care involvement, perceived risk and fear of contracting AIDS, and willingness to and satisfaction with care for AIDS patients. This can partly be attributed to a better understanding of the transmission and disease processes. Nurses who expressed more fear of contracting AIDS, however, also tended to report significantly higher levels of discomfort. The authors point out that other job correlates such as job tension, workload demands, and shift work are also contributors that should be explored in future research.

A pilot study was conducted by van Wissen and Siebers (1993) to determine nurses' attitudes with respect to HIV and AIDS exposure. Of 286 nurses surveyed who handled blood, 132 (49.4 percent) always wore gloves, and only half

of the respondents (n = 148, or 51 percent) treated all body fluids as potentially HIV positive. The possible attrition rate from nursing positions in the canvassed hospital was 2.8 percent, with a further 43 (15 percent) undecided about resigning from their post. This study demonstrates that further safety and education needs should be attended to or reinforced.

Baker (1993) reported survey results from studies conducted in 1986 and again in 1990 in New York on 2 separate samples of nearly 600 nurses. About half the nurses in each study stated they feared contagion. The number of nurses indicating they had the right to refuse to care for AIDS patients declined by 12 percent, even though 35 percent of the nurses maintained this position (which could have an impact on developing a therapeutic relationship). The change in attitude is attributed to education about AIDS.

Managing needlestick injuries in the health care setting is vitally important in order to reduce exposure to blood-borne pathogens such as HIV and hepatitis. As needlestick injuries occur for a variety of reasons, several approaches must be utilized to combat the problem. In addition, health care providers' attitudes and fears of contagion need to be explored further, as all of these factors impact quality of care, turnover, and outright leaving of the nursing profession. These include instituting appropriate and effective engineering controls, ensuring compliance with regulatory mandates and work practice policies and guidelines, conducting surveillance programs, and providing useful educational instruction. Adequate evaluation of injury prevention programs is essential in order to determine the effectiveness of interventions, and continued research is critical to measure outcomes in terms of increased injury rates, attitudes and behavior, and intervention effectiveness.

Violence Toward Health Care Workers

An emerging occupational health concern related to both injury and stress in the workplace is the risk of violence in general and toward health care workers. Homicides in the general workplace have gained prominence in recent years, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics counted 1,063 work-related homicides in 1993, most related to robbery (BLS, 1994a). In addition, the BLS recently began surveying the number of nonfatal assaults and acts of violence in private workplaces that required injured wage and salary workers to take off a workday or more. In 1992, about 22,400 such incidents were reported, each requiring, on average, about 5 days away from work to recuperate. A sizable proportion of the victims of nonfatal violence were care givers in nursing homes and hospitals. Ironically, some of these workers were injured by intransigent patients who resisted their assistance; others were assaulted by patients prone to violence. Most of these care givers were female nurses and their aides, and typically they required about 3 to 5 days away from work to recuperate from their injuries (BLS, 1994a).

There are various definitions of violence ranging from verbal threat, feelings of being threatened, to actual injury from assault (Aiken, 1984; Jones, 1985; Carmel and Hunter, 1989; Greenfield et al., 1989; Morrison, 1989). The lack of a standardized definition or a vagueness in definition makes it difficult to truly assess the problem and contributes to the underestimation of the scope of the problem (Lanza, 1991; Lipscomb and Love, 1992). In fact, Lion and colleagues (1981) reported that staff assaults by patients in a state psychiatric facility were underreported fivefold, which may reflect institutional policies and staff tolerance (Haller and DeLuty, 1988).

To date, the problem of violence in health care settings has focused mainly on psychiatric settings (Bernstein, 1981; Rix, 1987; Lanza, 1988). Poster and Ryan (1989) surveyed 154 psychiatric nurses and found that 74 percent of those responding indicated that staff members working with mentally ill patients could expect to be assaulted during their careers, and in fact 73 percent had already been assaulted. Lanza (1983) reports that staff assaults by patients in mental health facilities is as high as 80 percent.

In a study of 600 patients in a British psychiatric hospital, Larkin and colleagues (1988) found that more than 200 patients engaged in assaultive behavior. In another study, Lanza (1983) found that 40 psychiatric nurses in a VA hospital reported being assaulted an average of 7 times in their career (mean years of psychiatric experience was 6). Assaults were described as being grabbed, hit, choked, knocked out, and thrown about.

Using the Occupational Safety and Health (OSHA) definition of injury, Carmel and Hunter (1989) conducted a 1-year study of injuries in a 973-bed California maximum security hospital and found that injuries to staff occurred at a rate of 16 per 100 staff. In contrast, the rate for work-related injuries reported to OSHA in 1989 for all industries combined was 8.3 per 100 full-time workers (BLS, 1991).

Violence toward all health care workers appears to be on the rise (Lanza, 1992; Lipscomb and Love, 1992). Some have speculated about the cause for the increased violence in hospitals. Increased violence in the general population as a means of solving problems, increased use of mind-altering drugs and alcohol abuse, and the increased availability of weapons may all contribute to the problem of violence in the health care setting. Jones (1985) reported that in a VA the nursing assistants, followed by the nurses and physicians, were most likely to be assaulted. Lavoie and colleagues (1988) reported on results of a survey of 127 emergency room medical directors. Forty-three percent of the sample indicated at least one physical attack on a medical staff person per month, which included violent acts that resulted in death.

McCulloch and colleagues (1986) report that weapon carrying in psychiatric facilities and emergency rooms is not uncommon and that staff are usually unable to predict who the weapon carriers are. Several additional studies have reported on the issue of weapons in hospital settings. Wasserberger and colleagues (1989)

reported that over a 9-year period nearly 5,000 weapons were confiscated from 21,456 patients at a Los Angeles trauma center. In Lavoie and colleagues' (1988) study of emergency room medical directors, nearly 20 percent of the respondents reported at least 1 threat with a weapon per month and nearly 50 percent of the hospitals had confiscated weapons. Goetz and colleagues (1991) reported that 11 percent of psychiatric patients admitted to an emergency department during a 20-month period and 0.4 percent of all medical patients were searched for weapons, with 17.3 percent and 15.7 percent found to be carrying weapons, respectively.

Several environmental or administrative factors are thought to contribute to violence against health care workers. These include limited training in the management of assaultive behavior or in containing or restraining an assailant; short staffing and use of agency staff; and the day shift tour of duty, when there are generally increased levels of activity on the wards (Infantino and Musingo, 1985; Jones, 1985; Carmel and Hunter, 1990).

As the number of elders in the general population increases, the number of nursing home patients is also likely to increase with a concomitant rise in staff. The largest proportion of staff in nursing homes are NAs; only one study, however, has been reported on violence in this population. Lusk (1992) reported on results of focus groups with NAs in seven nursing homes. Aides indicated "they get hurt everyday, … and that patients hit, scratch, pull hair, kick, bite and pinch" (p. 239). In addition, aides expressed concern about the lack of protection afforded them.

The actual costs of violence toward health care workers have not been widely studied; Carmel and Hunter (1989) reported, however, that of 121 staff injuries, 43 percent of those injured lost time from work with 13 percent of those injured absent more than 21 days. Lanza and Milner (1989) reported that for 99 staff assaults nearly 40 percent resulted in lost work time with 12 percent requiring more than a month off duty for full recovery. The actual dollar costs were not reported.

The study of violence toward health care workers as an occupational hazard is relatively new. The emphasis in the studies reported is primarily on reporting data relative to incidence and prevalence. More emphasis must be placed on identifying root causes of violence in these settings and prevention strategies to reduce health care worker risk. Risk factors such as poor staffing patterns, reduced staffing levels, and violence containment issues must be addressed by management in order to afford a safe work environment and reduce the emotional impact of this type of violence on workers.

Stress And Nursing

Packard and Motowidlo (1987) have stated that:

When patients require bodily care, understanding, empathy and full, uncondi-

tional acceptance, or when many complex tasks are required unexpectedly, hospital nurses find practical, tangible evidence of the worth of their talents, skills, and commitment to people. But when nurses recognize that their work is undervalued, underappreciated, disparaged, taken for granted and when in addition they are treated discourteously or even pitted against one another for the meager rewards of their jobs, then nurses properly regard such stressors as undesirable.

The authors purport that when this happens job performance is poorer.

It is well documented in the literature that nursing work results in significant amounts of stress leading to a variety of work-related problems such as absenteeism, staff conflict, staff turnover, decreased morale, and decreased practice effectiveness (MacNeil and Weisz, 1987; Doering, 1990; Hiscott and Connop, 1990; Rees and Cooper, 1992; Fielding and Weaver, 1994). The review of the literature that follows examines the relationship between nursing work and stress and related outcomes, emphasizing the impact on work and performance.

In an early study, Gentry and colleagues (1972) examined the psychological responses of 34 RNs working in various intensive care units (ICU) and non-ICU settings within a Medical Center–Veterans Administration hospital (VAH) complex. A battery of standardized psychological test measures was used. Medical Center ICU (MC-ICU) nurses reported more depression, hostility, and anxiety then did non-ICU nurses and nurses in the VAH critical care units (CCU).

The MC-ICU settings produced more complaints and ones concerned with an overwhelming workload, limited facilities and space, inadequate help for proper patient care, too much responsibility, too little continuing education, poor organization, excessive paperwork, inadequate communication with physicians, transition of personnel, and intrastaff tension. The authors contend that:

the finding that MC- and VAH-CCU nurses differed rather markedly both in their levels of affect and their likes/dislikes about their work was indeed interesting, since both groups perform essentially the same duties with the same type of patients in virtually identical physical surroundings. What it suggests is that the CCU setting as such is not intrinsically stressful, but rather becomes so when adequate help is not available to care for the patients properly, when nurses are not provided with necessary continuing education, and when a deliberate effort is not made to instill a feeling of pride and "team spirit" within the staff as a whole.

Packard and Motowidlo (1987) conducted a survey study for 5 hospitals to assess the relationship between subjective stress, job satisfaction, and job performance in 366 hospital RNs and LPNs. A second survey instrument was sent to the supervisor and a coworker of the primary nurse subject (n = 165 and 139, respectively) asking about the nurse's work performance. Increased stress encounters diminished both job satisfaction and job performance and increased episodes of depression. Job satisfaction was not related to job performance, but

depressed and hostile nurses had lower job performances than did nurses with little or no depression or personal hostility.

Early studies have purported that critical care and intensive care nurses experience more stress than nurses in other areas. Research has not consistently validated this concept, however. MacNeil and Weisz (1987) measured the level of psychological distress experienced by critical care nurses (n = 80) and non-critical-care nurses (n = 106) employed in a large acute care hospital, and its relationship to absenteeism. Non-critical-care nurses reported significantly higher psychological distress scores than did the critical nursing group and nearly twice the rate of absenteeism. These results may indicate better staffing or orientation in critical care nursing. Alterations in the work environment and conditions and stress management programs are needed to reduce nurses' distress.

Foxall and colleagues (1990) surveyed 138 nurses including 35 ICU nurses, 30 hospice nurses, and 73 medical-surgical nurses to determine differences in stress levels among the groups. While there were no overall significant differences among the groups with respect to stress levels, significant differences did occur for subscales: ICU and hospice nurses perceived significantly more stress related to death and dying than did medical-surgical nurses; ICU and medical-surgical nurses perceived significantly more stress related to floating than did hospice nurses; and medical-surgical nurses perceived significantly more stress related to work-overload and staffing than did ICU and hospice nurses. While the effects of job stress on the quality of patient and family care were not specifically addressed, stress management programs were encouraged, particularly in the area of death and dying, to alleviate burnout and facilitate more effective care. In addition, work environment issues such as increased staffing levels and decreased floating were encouraged to minimize work overload and the potential for reduced quality of care. Similar findings were reported by Boumans and Landeweerd (1994) who studied 561 ICU and non-ICU nurses from 36 units in 16 hospitals. Non-ICU nurses had more work pressure, absenteeism, and health complaints than did the ICU nurses.

Yu and colleagues (1989) surveyed a random sample of 952 RNs obtained through a statewide nurses association membership list to identify specific job stressors across 10 clinical specialties. Results indicated that stress seems to arise from the overall complexity of nurses' work rather than specific tasks. Stressors were uniform across specialty areas, with the greatest levels reported in administration, cardiology, medical-surgical, and emergency room nursing.

Several studies have examined stress in other types of nursing fields. Jennings (1990) found that among 300 U.S. Army head nurses in 37 different army hospitals, stress resulted in psychological symptoms as measured by the Brief Symptom Inventory. Of particular importance is the notion that managers bear the responsibility for attenuating the stress experienced by staff. The question raised is: Can managers who are experiencing psychological distress them-

selves adequately intercede to reduce staff stress, as well as manage their units efficiently and effectively?

Using several instruments, Power and Sharp (1988) compared stress and job satisfaction among 181 nurses at a mentally handicapped hospital and 24 hospice nurses. Hospice nurses characteristically reported stress as primarily associated with death and dying and with inadequate preparation to meet the emotional needs of patients and families, but did not report significantly high workload stress as had been observed in other studies. This may be due partly to the relatively high staff-to-patient ratio in a hospice setting. Conversely, nurses working with mental handicapped patients reported significantly more stress associated with workload, conflict with other nurses, and the nursing environment.

In a study of neurosurgical nurses, the authors interviewed several nurses about aspects of neurosurgical nursing that were perceived as stressful by staff. Findings suggest that being exposed to life-and-death situations among young children, being short of essential resources, being on duty with too few staff, and dealing with aggressive relatives constituted major stressful events. Comments made by staff suggested that performance at work is adversely influenced by stress (Snape and Cavanagh, 1993). These findings were echoed in a study of dialysis nurses who also indicated that work load is a major contributing factor not only to overall stress and work performance, but to burnout as well (Lewis et al., 1992). In addition, a sample of 155 members of the Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses reported that the relapse or sudden death of a favorite patient was their greatest source of stress. The second most common stressor was a workload perceived as too great to give quality patient care (Emery, 1993).

Hawley (1992) surveyed 69 emergency room nurses to identify sources of stress and effective strategies for addressing them. Repeatedly, nurses described inadequate staffing and resources, too many nonnursing tasks, changing trends in emergency department use, and patient transfer problems as having considerable impact on their ability to provide quality patient care. Nurses were also stressed by continual confrontations with patients and families who exhibit crisis behavior. Staff also reported that a shortage of nursing staff, especially during busy periods and at night, was particularly stressful and that because of these shortages they were unable to give adequate care to patients. Adding untrained relief staff compounded the stress burden.

In order to compare sources and outcomes of stress among hospital pharmacists and nurses, Wolfgang and colleagues (1988) randomly surveyed 1,002 RNs and 1,006 pharmacists using national mailing lists. While 462 (46 percent) nurses and 465 (46 percent) pharmacists returned surveys, only 263 (69.4 percent of respondents) and 107 (27.6 percent of respondents) were hospital-based and therefore useable. All subjects completed the Health Professions Stress Inventory and moderate stress levels were found for both groups with significant differences noted. Interruptions, poor opportunities for advancement, inadequate staffing, excessive workload, and inadequate pay were considered to be very

stressful by both groups. The pharmacists considered a lack of challenge in their work to be more stressful than did the nurses. Situations relating to patient care, such as being uncertain about what to tell a patient or family members about the patient's condition or treatment and caring for terminally ill patients, were perceived by nurses as being more stressful than they were perceived by the pharmacists. Forty-eight of 106 pharmacists and 95 of 259 nurses said that they would probably not pursue the same career if they started over again. While some stressful situations are similar for both groups, sources of stress for nurses tend to be more patient-care related than for pharmacists.

Gordon and colleagues (1993) surveyed all nurses in the Haemophilia Nursing Network Directory, compiled by the National Haemophilia Foundation, to investigate distress in this group of nursing practitioners. Questionnaires were returned by 75 percent (136 of 181) of those surveyed. Areas associated with the greatest distress were: (1) failure of patients to take steps to prevent transmission of HIV; (2) fear of getting infected; and (3) the repeated loss experienced as patients died from infection. Nurses working with haemophiliacs for 11 to 15 years were particularly vulnerable to feelings of guilt for having participated in the treatment that resulted in HIV infection. Looking for a new job was related to all major sources of distress.

Cull (1991) and van Servellen and Leake (1994) describe oncology nurses as having significant amounts of stress associated with their practice and that absenteeism, high staff turnover, poor quality-control of work, poor industrial relations, and emotional exhaustion are likely results. Recommendations include reviewing institutional policies and work conditions to reduce stressors as well as utilizing support groups.

Scalzi (1990) surveyed 75 top level nurse executives in all hospitals in a large metropolitan city to examine the relationships between role conflict, ambiguity, and depression and job satisfaction and stress. Three predominant job stressors were examined and designated respectively as: the overload stressor, because it was composed of items that dealt primarily with conflict and overload due to too many expectations; the quality concern stressor, which included stress generated by poor quality of nursing staff, medical staff, and patient care; and the lack of support stressor, which included stress items measuring lack of support from hospital administration and from immediate subordinates, and difficult relationships with other departments.

These executives perceived high role conflict, moderately high role ambiguity, and moderately high levels of depression symptoms. Both role conflict and role ambiguity were positively and significantly correlated with depressive symptoms, and higher levels of depressive symptoms were significantly associated with both lower levels of job satisfaction and higher levels of quality concern stress. Role conflict was positively correlated with role ambiguity and stress from quality concerns and role conflict was negatively correlated with job satisfaction.

The quality concern stressor was the source of the most severe job stress and had strong associations with increased depressive symptomatology, increased role conflict, and decreased job satisfaction. The author states that this particular job-related stress is specific to the health care industry and involves both ethical and professional responsibilities to provide safe (quality) care.

Research studies on shift work have reported adverse effects on workers' health, performance, and mental and physical fitness (Jung, 1986; Gold et al., 1992; Todd et al., 1993). Shift workers have reported a lower sense of well-being with lower participation rates in social organizations, engagement in more solitary activities, higher incidences of family and sexual problems, higher rates of divorce than day workers, and decreased work performance. Gold and colleagues (1992) conducted a hospital-based survey on shift work, sleep, and accidents among 635 Massachusetts nurses. In comparison to nurses who worked only day and evening shifts, rotators had more sleep-wake cycle disruption and nodded off more at work. Rotators had twice the odds of nodding off while driving to or from work and twice the odds of a reported accident or error related to sleepiness. Factors that affect adjustments to shift work include the type of shift work schedule, the frequency of the schedule changes, the degree to which workers adjust their social, dietary, and sleeping habits to coincide with their shift work schedule, and the age of the worker. Research has shown that workers who rotate shifts have more difficulty adjusting to schedules that change more frequently than once every 2 to 3 weeks. Periods of less than 2 to 3 weeks do not allow sufficient time for workers' circadian rhythms to resynchronize to a new shift assignment. Rotating shifts work better if they change clockwise, from day to evening to night, instead of from day to night and then evening shifts (Jung, 1986). Application of circadian principles to the design of hospital work schedules may result in improved health and safety for nurses and patients.

In a study related to working hours, Todd and colleagues (1993) surveyed nurses who worked 12-hour shift rotations and who reported decreased satisfaction with their jobs, conditions of work, and patient care, and problems with domestic and social arrangements. The vast majority (83 percent) reported that they did not want to go on working the shift and there was support for the view that recruitment to nursing would be adversely affected by the shift. A further discussion of shift work as it relates to burnout is presented later.

Burnout in Nurses

Berland (1990) discusses the issue of burnout in nurses at Vancouver General Hospital and factors that influence burnout, including increasing patient activity, greater family needs, higher professional standards, and static hospital budgets that often result in staff shortages and reduced quality of care. To address the problem, the hospital administration empowered head nurses to restrict patient admission to their unit to protect staff nurses from burnout. After 18

months, evaluation of the new policy indicated that staff nurses felt more in control of their workload and could better shape and improve quality of care for patients.

Beard (1994) reported findings from studying stress and ''floating" in 42 nurses in a community hospital. The nurses served as their own controls when they were not floating. Using the Derogates Stress Profile, results showed significant stress levels were produced when the nurses floated. The resultant impact was increased turnover, reduced patient and physician satisfaction, and decreased productivity.

Using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, Kandolin (1993) studied 286 Finnish nurses to determine if burnout was more common among those who experienced shift work compared to those who did not. It was reported that more than one-third of the nurses often experienced high levels of time pressure in their work, and 10 percent of the nurses reported working at a workplace with a tense social atmosphere. Female nurses in 3-shift work had significantly more stress symptoms and ceased to enjoy their work more often than women in 2-shift work, which relates to loss of enthusiasm, efficiency, value placed on work, and work positivity. There were no gender differences in burnout.

Keim and Robinson (1992) also report increased levels of stress, described by third-shift nurses as being related to lack of supervisor support, work involvement, and peer cohesion. The authors point out that nursing shortages and increased vulnerability to stress may result in many nurses leaving their jobs to relieve stress and eventual burnout.

Pines and Maslach (1978) have defined burnout as "a syndrome of physical and emotional exhaustion involving the development of a negative self-concept, negative job attitude and loss of concern and feeling for clients" (p. 236). Husted and colleagues (1989) state that the nurse who is experiencing burnout often is disgruntled, unhappy, complaining, fatigued, impatient with self, short with patients and their families, rigid, distant from coworkers, quick to anger and, in general, unpleasant to be around. Fortunately, when a cluster of these symptoms occurs, the nurse is not around too often or too long. Absenteeism increases and turnover results. A ripple effect becomes operational and observable. The unhappy nurse seeks coworkers who will listen and sympathize. As absenteeism increases, the workload of coworkers increases proportionately, which contributes to the spread of burnout.

With increasingly successful technology, younger and smaller neonates are surviving to become chronically ill with the need for many months of intensive care (Oehler et al., 1991). Thus, neonatal nurses are reported to be victims of stress and subsequent burnout and the authors sought to study this phenomenon. Specific stressors within the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) are (1) ethical dilemmas surrounding life-and-death situations of critically ill neonates; (2) death of an infant; (3) demands on the family of a high-risk infant; (4) challenging and

constantly changing technology in neonatal nursing; and (5) conflicts of understaffing in a busy NICU (Marshall and Kasmen, 1980).

Oehler and colleagues (1991) surveyed 49 RNs and LPNs working in a neonatal intensive care unit of a large major medical center using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, and social support measures. On the Maslach Burnout Inventory, subjects scored in a moderate range of burnout for emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and in a high range of burnout for sense of personal accomplishment. Stepwise regression analyses revealed that higher job stress scores, higher anxiety scores, perception of less supervisor (head nurse) support, and less experience were associated with higher burnout subscale scores. This type of nursing, wherein the needs of the patients and family are high, can be very emotionally fatiguing. Supervisory support and ongoing information about coping strategies are essential.

Because of the nature of nursing work, the nursing profession may be the helping profession most at risk of burnout (Johnson, 1992). Duquette and colleagues (1994) describe burnout as having psychological, physical, and behavioral components:

Often the first symptoms that appear are the sensations of emotional exhaustion and extreme tiredness. The person lacks energy; is irritable, anxious, and angry; and has feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. The person often complains of various manifestations of a physical nature such as headaches, backaches, and gastrointestinal disorders. The emotionally exhausted person develops negative attitudes and feelings toward patients and may become indifferent, cold, and cynical. The person feels frustrated with his or her work, may develop feelings of guilt and failure, and may have a negative self-image as well as a tendency to be absent often from work and may seek other employment (p. 337).

The authors indicated that organizational stressors influence the development of burnout, particularly role ambiguity, staffing, and workload; age, with younger nurses being more susceptible to seeing their role as more ambiguous and their workload heavier; and buffering factors including hardiness, social support, and coping.

In another study by Dolan (1987) that comprised each of 30 psychiatric, general duty, and administrative nurses, the study subjects completed the Maslach Burnout Inventory and job satisfaction questionnaire. Job satisfaction was inversely related to burnout in a descending order from general duty, to psychiatric, to administrative nurses. The rapid turnover of patients in general hospitals, compared to psychiatric hospitals, was cited as increasing the workload for the general nurse. Nurses felt that having to treat too many patients in too short a time restricts their need to meet their own professional standards and to attend fully to the psychological as well as the physical needs of the patient.

Turnover

Eriksen and colleagues (1992) describe two potentially negative consequences of consistently high workloads in an understaffed situation: decreased quality of care and lower job satisfaction, which may lead to increased nurse turnover. An RN-LPN nurse partnership model of care was implemented in the critical care setting to prevent these potential consequences. The purpose of the model program was to develop "qualified extenders" for the critical care staff nurse so as to reduce workload and thereby affect the quality of care given. In this model, vocational nurses were given an 8-week education and orientation program termed the "licensed vocational nurse critical care specialty program." Certain aspects of direct and indirect nursing care were taught that were then to be considered tasks delegated to the licensed vocational nurse extenders. Evaluation of the program revealed statistically significant increases in nurse job satisfaction; perceptions of reduced workload and stress; a perception by RNs and physicians of increased nursing care quality; decreased RN turnover and sick time; and a positive perception of the role of the LPN in the critical care unit.

Mann and Jefferson (1988) describe many reasons for high turnover rates on medical intensive care units (MICU) including heavy workloads, lack of recognition, and lack of administrative support and leadership that can lead to stress. The authors surveyed 47 nurses in the MICU and found that understaffing and workload were the most stressful problems that influenced the quality of care. Proactive measures were implemented to reduce problems.

Hinshaw and colleagues (1987) examined retention strategies of nursing staff, as turnover is considered detrimental to maintaining quality of care and containing health care costs. The investigators analyzed questionnaire data from 1,597 nursing staff members (RNs, LPNs, NAs) in both urban and rural settings, and diverse clinical areas. In general, the study results emphasized that job stress is buffered by satisfaction that in turn leads to less anticipated turnover. The satisfiers can be converted into organizational strategies for retaining nursing staff. The major stressors to be buffered were lack of team respect and feelings of incompetence, while the primary satisfiers were professional status and general enjoyment in one's position, which correlated significantly with the ability to deliver quality nursing care.

Ackerman (1993) notes the importance of retaining pediatric intensive care unit staff and points out that high rates of turnover result in insufficiency in meeting patient care needs and compromised care. The author stipulated that perhaps the most important retention strategy is the initial recruitment of individuals who are most likely to fit in with the established goals of the unit. Once the best possible candidate has been hired, retention depends on maintaining the individual's job satisfaction, which may be accomplished via mechanisms such as: (1) providing a reasonable workload; (2) providing effective communication between the manager and the staff; (3) having a manager with an effective man-

agement style; (4) ongoing and meaningful nurse–physician collaboration; and (5) reasonable compensation for work being done. In addition, reasonable workload must assume that patient care assignments are such that the staff can take pride in the quality of the job done, while delivering safe, consistent bedside care without the addition of excessive overtime hours. When unpredicted shortages occur, based on increased patient acuity or census or decreased staff availability, these shortages must be managed in ways that preserve the functioning of the unit and the morale of the remaining staff. Possible responses include the use of "floaters," agency nurses, or even closing beds for the short term.

Shanahan (1993) compares and contrasts factors that affect recruitment and retention of physical therapists and RNs. The author points out that professional staff shortages in hospital settings can drastically increase operating costs and compromise the quality of care. Lower quality of care can limit the ability of the hospital to attract customers and staff, and can increase the hospital length of stay with a concomitant increase in costs. While salary and compensation are considered important incentive factors in retention, other factors such as image and job satisfaction remain important considerations. A disturbing finding by Porter and colleagues (1989), however, is that only 72 percent of nurses have a positive image about their profession. This was a lower perception than that of the general public (84 percent) or of physicians (100 percent). Hospital chief executive officers ranked nursing as the most significant factor contributing to quality health care (97.3 percent). Hospital management must address issues related to turnover in order to fully reach quality-of-care demands.

Dolan and colleagues (1992) discuss issues surrounding the propensity of nursing staff to quit, which has been acknowledged as the best predictor of turnover. Behaviors related to stress, burnout, and depression are notable and can have a subsequent impact on quality of care and turnover. The cost for a single nurse replacement is estimated at about $2,000. The investigators surveyed 1,237 staff who worked in 30 Quebec hospital emergency rooms and intensive care units about 14 job demands (the response rate was 84 percent). Results indicated that lack of professional latitude (which included restricted autonomy, skill underutilization, and lack of participation in clinical decision making), clinical demands, role difficulties, and workload problems all contributed to the propensity to quit. The authors suggested that interventions aimed at improving the quality of work and the general work-related quality of life should be implemented to enhance employee mental health, reduce rates of turnover, and curb costs.

The work of nurses is repeatedly cited as being highly stressful for its practitioners and can result in burnout. While inadequate staffing levels are considered the major cause of stress for nurses, other factors such as the dying and death of patients, work overload, shift work, decreased job satisfaction, inadequate resources, replacement orientation, role conflict, and lack of management support are frequently implicated as significant causes of stress and burnout in nursing.

Many authors indicate that the quality of nursing care is seriously jeopardized and that nurses often leave nursing as a result of the burnout syndrome they suffer (Anonymous, 1986; Masterson-Allen et al., 1987; Lucas et al., 1993).

Many organizational factors have been cited that influence nursing stress, burnout, and productivity in nursing care, and that may result in short-term or long-term absenteeism. Other than personal illness, however, child care problems are the primary personal factors that contribute to absenteeism (Miller and Norton, 1986; Bourbonnais et al., 1992). Although it is unclear if this problem is consistent across occupations, available data indicate that handling child care issues falls primarily to the mother (Roberts and McGovern, 1993). As nursing and nursing-related work is performed mostly by women, this clearly becomes an issue in the nursing work force. Because of a nearly $1 million cost associated with nursing absenteeism and concern about loss of productivity, quality of patient care, and decreased morale, an analysis of absenteeism was conducted in a 3-hospital system in the mid-southern region of the United States. A total of 865 RNs, LPNs, unit secretaries, and medical attendants were surveyed, with 90 percent women responders. Results indicated that issues related to child care were the major contributor to absenteeism with 87 percent of those surveyed indicating that they missed work due to child illness. Other important findings included significant conflict between parent and employee roles (e.g., leaving sick child at home or leaving children at home unsupervised); staffing and scheduling difficulties resulting in employees admitting to missing work (e.g., too long stretches of work days and inadequate staffing); and indifferent attitudes about sick leave (e.g., administrators should not complain if employees were absent without pay). Attitudes of professional and nonprofessional staff were similar. Findings raised serious concern about productivity, lack of continuity of care, and resultant implications for quality of patient care.

Hospitals are plagued with high rates of turnover and absenteeism as many nurses trying to cope with stress move from hospital to hospital (Gelfant, 1990). While staffing levels are reduced, the number of patients stay the same, the complexity of the work increases, and the work is expected to be done with the same level of quality. Consequently stress, guilt, and burnout ensue (Lees and Ellis, 1990).

Health care administrators must address the issues of the impact of organizational stressors on nurses if there is to be any hope of resolving the problem (Whitley and Putzier, 1994). New approaches to staff selection and recruitment, flexibility in staffing, increased resources, and increased decision making by nurses is essential.

General Critique Of Studies

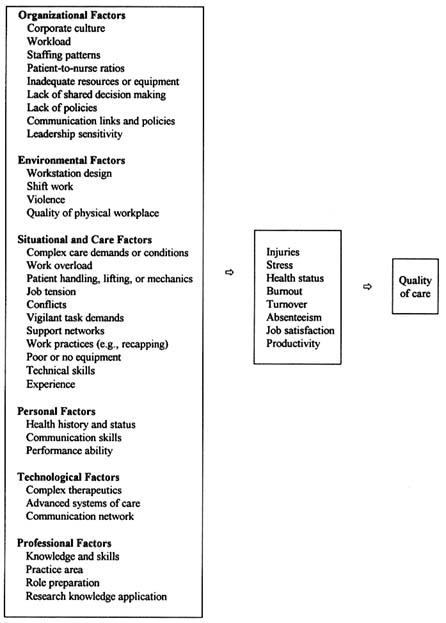

The studies discussed provide valuable information on the problem of injury and stress in nursing and the relationship of this problem on nursing care. Figure 1

summarizes these points. The studies purport that inadequate staffing, staffing patterns, excessive patient-to-nurse ratios, clinical issues (e.g., patient deaths), poorly designed equipment, lack of administrative support, lack of decision making authority, lack of resources, training and education, poor body mechanics, and pressure to work in at-risk conditions are significant contributors to the problem. The data provided are somewhat limited, however, due to lack of replication and little evidence of causality with respect to quality care outcomes. In addition, sample sizes and sampling procedures are of concern particularly in terms of the generalizability of findings.

Many of the studies are descriptive, cross-sectional, and retrospective in design, and report anecdotal findings. To have a full meaning of outcomes measurement, experimental and cohort studies should be conducted. Not enough evidence is presented on the effectiveness of equipment design and other types of intervention strategies (e.g., improved staffing, child day care availability) that may improve working conditions. In addition, few data are available on the costs related to the impact of nursing injury and stress, particularly as they relate to quality and patient care. In conclusion, many challenges exist to effectively manage and alleviate injury and stress in the nursing workplace environment. Risk reduction is of prominent importance but research in the relevant areas is sorely lacking.

References

Ackerman, A.D. Retention of Critical Care Staff. Critical Care Medicine 21(9 Suppl):S394–S395, 1993.

Aiken, G.J.M. Assaults on Staff in a Locked Ward: Prediction and Consequences. Medicine, Science and the Law 24(3):199–207, 1984.

AHC (American Health Consultants). One Third of Needlesticks Go Unreported at Hospital. Hospital Infection Control 17(18):107, 1990.

Anonymous. What Really Makes Nurses Angry. RN 49(1):55–60, 1986.

Arad, D., and Ryan, M. The Incidence and Prevalence in Nurses of Low Back Pain: A Definitive Survey Exposes the Hazards. Australian Nurse Journal 16:44–48, 1986.

Baer, C., and Longo, M.S. Talking About It: Allaying Staff Concerns About AIDS Patients. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 27(10):30–32, 1989.

Baker, L. Half of Nurses Fear Contracting AIDS. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 31(6):40–41, 1993.

Barrick, B. The Willingness of Nursing Personnel to Care for Patients with Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome: A Survey Study and Recommendations. Journal of Professional Nursing 4(5):366–372, 1988.

Beard, E.L. Stop Floating—The Next Paradigm Shift? Journal of Nursing Administration 24(3):4, 1994.

Becker, C, Cone, J., and Gerberding, J. Occupational Infection with Human Immunodeficiency Virus: Risks and Risk Reductions. Annals of Internal Medicine 110(8):653–656, 1989.

Becker, M.H., Janz, N.K., Band, J., Bartley, J., Snyder, M.B., and Gaynes, R.P. Noncompliance with Universal Precautions Policy: Why Do Physicians and Nurses Recap Needles? American Journal of Infection Control 17(46):232–239, 1990.

Berland, A. Controlling Workload. Canadian Nurse 86(5):36–38, 1990.

Bernstein, H.A. Survey of Threats and Assaults Directed Toward Psychotherapists. American Journal of Psychotherapy 35(4):542–549, 1981.

BLS (Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor). Occupational Injuries and Illnesses in the United States by Industry, 1989. Bulletin 2379, 1991.

BLS. Issues in Labor Statistics. Violence in the Workplace Comes Under Closer Scrutiny. Summary 94-10. August, 1994a.

BLS. Issues in Labor Statistics. Worker Safety Problems Spotlighted in Health Care Industries. Summary 94-6. June, 1994b.

Boland, B. Fear of AIDS in Nursing Staff. Nursing Management 21(8):40–44, 1990.

Boumans, N.P., and Landeweerd, J.A. Working in an Intensive or Non-Intensive Care Unit: Does it Make Any Difference? Heart and Lung 23(1):71–79, 1994.

Bourbonnais, R., Vinet, A., Meyer, F., and Goldberg, M. Certified Sick Leave and Work Load. A Case Referent Study Among Nurses. Journal of Occupational Medicine 34(1):69–74, 1992.

Carmel, H., and Hunter, M. Staff Injuries from Inpatient Violence. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40(1):41–46, 1989.

Carmel, H., and Hunter, M. Compliance with Training in Managing Assaultive Behavior and Injuries from Inpatient Violence. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41(5):558–560, 1990.

Carney, R.M. Protect your Nursing Athletes! Nursing Management 24(3):69–71, 1993.

Cato, C., Olson, K., and Studer, M. Incidence, Prevalence and Variables Associated with Low Back Pain in Staff Nurses. AAOHN (American Association of Occupational Health Nurses) Journal 321–327, 1989.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control). The Second 100,000 Cases of Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome—United States, June 1981–December 1991. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 41(2):28–29, 1992.

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 5(19), 1994.

Cull, A.M. Studying Stress in Care Givers: Art or Science? British Journal of Cancer 64(6):981–984, 1991.

Doan-Johnson, S. Taking a Closer Look at NeedleSticks. Nursing 92 22(8):24, 27, 1992.

Doering, L. Recruitment and Retention: Successful Strategies in Critical Care. Heart and Lung 19(3):220–224, 1990.

Dolan, N. The Relationship Between Burnout and Job Satisfaction in Nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 12(1):3–12, 1987.

Dolan, S.L., Van-Ameringen, M.R., Corbin, S., and Arsenault, A. Lack of Professional Latitude and Role Problems as Correlates of Propensity to Quit Amongst Nursing Staff. Journal of Advanced Nursing 17(12):1455–1459, 1992.

Duquette, A., Kerouac, S., Sandhu, B.K., and Beaudet, L. Factors Related to Nursing Burnout: A Review of Empirical Knowledge. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 15:337–358, 1994.

Editorial. Transmission of Hepatitis C via Blood Splash into Conjunctiva. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases 25:270–271, 1993.

Emery, J.E. Perceived Sources of Stress Among Pediatric Oncology Nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing 10(3):87–92, 1993.

English, J.F. Reported Hospital Needlestick Injuries in Relation to Knowledge/Skill, Design, and Management Problems. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 13(5):259–264, 1992.

Eriksen, L.R., Quandt, B., Teinert, D., et al. A Registered Nurse–Licensed Vocational Nurse Partnership Model for Critical Care Nursing. Journal of Nursing Administration 22(12):28–38, 1992.

Feldstein, A., Valanis, B., Vollmer, W., et al. The Back Injury Prevention Project Pilot Study: Assessing the Effectiveness of Back Attack, an Injury Prevention Program Among Nurses, Aides, and Orderlies. Journal of Occupational Medicine 35(2):114–120, 1993.

Fielding, J., and Weaver, S.M. A Comparison of Hospital- and Community-based Mental Health Nurses: Perceptions of their Work Environment and Psychological Health. Journal of Advanced Nursing 19(6):1196–1204, 1994.

Foxall, M.J., Zimmerman, L., Standley, R., and Bene, B. A Comparison of Frequency and Sources of Nursing Job Stress Perceived by Intensive Care, Hospice and Medical-Surgical Nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing 15(5):577–584, 1990.

Garg, A., Owen, B.D., and Carlson, B. An Ergonomic Evaluation of Nursing Assistants' Job in a Nursing Home. Ergonomics 35(9):979–995, 1992.

Garrett, B., Singiser, D., and Banks, S.M. Back Injuries Among Nursing Personnel: The Relationship of Personal Characteristics, Risk Factors, and Nursing Practices. AAOHN (American Association of Occupational Health Nurses) Journal 40(11):510–516, 1992.

Gelfant, B.B. How the Environment Affects Turnover. Journal of Practical Nursing 40(1):33, 51, 1990.

Gentry, W.D., Foster, S.B., and Froehling, S. Psychologic Response to Situational Stress in Intensive and Nonintensive Nursing. Heart and Lung 1(6):793–796, 1972.

Gerberding, J.L. Management of Occupational Exposures to Blood-borne Viruses. New England Journal of Medicine 332(7):444–449, 1995.

Goetz, R.R., Bloom, J.D., Chenell, S.L., and Moorhead, J.C. Weapons Possession by Patients in a University Emergency Department. Annals of Emergency Medicine 20(1):8–10, 1991.

Gold, D.R., Rogacz, S., Bock, N., et al. Rotating Shift Work, Sleep, and Accidents Related to Sleepiness in Hospital Nurses. American Journal of Public Health 82(7):1011–1014, 1992.

Gordon, J.H., Ulrich, C., Feeley, M., and Pollack, S. Staff Distress Among Haemophilia Nurses. AIDS Care 5(3):359–367, 1993.

Greenfield, T.K., McNeil, D.E., and Binder, R.L. Violent Behavior and Length of Psychiatric Hospitalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40(8):809–814, 1989.

Greenwood, J.G. Back Injuries Can Be Reduced with Worker Training, Reinforcement. Occupational Health and Safety 55(5):26–29, 1986.

Haller, R.M., and DeLuty, R.H. Assaults on Staff by Psychiatric Inpatients: A Critical Review. British Journal of Psychiatry 152:174–179, 1988.

Hamory, B.H. Underreporting of Needlestick Injuries in a University Hospital. American Journal of Infection Control 11(5):174–177, 1983.

Harber, P., Billet, E., Gutowski, M., et al. Occupational Low Back Pain in Hospital Nurses. Journal of Occupational Medicine 27(7):518–524, 1985.

Hawley, M.P. Sources of Stress for Emergency Nurses in Four Urban Canadian Emergency Departments. Journal of Emergency Nursing 18(3):211–216, 1992.

Henderson, D.K., Fahey, B.J., Willy, M., et al. Risk for Occupational Transmission of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) Associated with Clinical Exposures. Annals of Internal Medicine 113(10):740–746, 1990.

Hinshaw, A.S., Smeltzer, C.H., and Atwood, J.R. Innovative Retention Strategies for Nursing Staff. Journal of Nursing Administration 17(6):8–16, 1987.

Hiscott, R.D., and Connop, P.J. The Health and Well-Being of Mental Health Professionals. Canadian Journal of Public Health 81(6):422–426, 1990.

Hudson, G. The Toxic Ecology of Work: Are the Carers Taking Care? Australian Nurse Journal 19(10):17, 1990.

Husted, G.L., Miller, M.C., and Wilczynski, E.M. Retention is the Goal: Extinguish Burnout with Self-Esteem Enhancement. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing 20(6):244–248, 1989.

Infantino, J.A., and Musingo, S.Y. Assault and Injuries Among Staff With and Without Training in Aggression Control Techniques. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36(12):1312–1314, 1985.

Jackson, M.M., Dechairo, D.C., and Gardner, D.F. Perceptions and Beliefs of Nursing and Medical Personnel About Needle-Handling Practices and Needlestick Injuries . American Journal of Infection Control 14(1):1–10, 1986.

Jagger, J. A New Opportunity to Make the Health Care Workplace Safer. Advances in Exposure Prevention 1(1):1–2, 1994a.

Jagger, J. Report on Blood Drawing: Risky Procedures, Risky Devices, Risky Job. Advances in Exposure Prevention 1(1):4–9, 1994b.

Jagger, J., Hunt, E.H., Brand-Elnagger, J., and Pearson, R.D. Rates of Needlestick Injury Caused by Various Devices in a University Hospital. New England Journal of Medicine 5:284–288, 1988.

Jagger, J., Cohen, M., and Blackwell, B. EPINet: A Tool for Surveillance of Blood Exposures in Health Care Settings. Essentials of Modern Hospital Safety 3:223–239, 1994.

Jennings, B.M. Stress, Locus of Control, Social Support, and Psychological Symptoms Among Head Nurses. Research in Nursing and Health 13(6):393–401, 1990.

Jensen, R.C. Back Injuries Among Nursing Personnel: Research Needs and Justifications. Research in Nursing and Health 10:29–38, 1987.

Johnson, C. Coping with Compassion Fatigue. Nursing 22(4):116–119, 1992.

Jones, M.K. Patient Violence Report of 200 Incidents. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 23(6):12–17, 1985.

Jorgensen, S., Hein, H.O., and Gyntelberg, F. Heavy Lifting at Work and Risk of Genital Prolapse and Herniated Lumbar Disc in Assistant Nurses. Occupational Medicine 44(1):47–49, 1994.

Jung, F. Shift work: Its Effect on Health Performance and Well-Being. AAOHN (American Association of Occupational Health Nurses) Journal 34(4):161–164, 1986.