5

The Market for New Contraceptives: Translating Unmet Need into Market Demand

Chapter 2 documents the existence of a considerable unmet need for contraception in both the industrial and developing economies of the world. The argument is made that there is a compelling public health1 case for broadening the portfolio of contraception options, for women and men everywhere. Chapters 3 and 4—most particularly the latter—offer rich evidence for new paths in contemporary science that could expand those options and answer specific and highly critical needs for which there are now no adequate or appropriate solutions.

Yet, as irrefutable as the need may be and as promising the science, response from pharmaceutical firms in the United States and western Europe will be conditioned by the difficulties of translating need and promise into a profitable market. The high costs and risks of committing to the development of any medical technology are such that no firm will undertake commercialization without at least a strong belief in the existence of a substantial market of consumers able and willing to pay, in other words, the existence of market demand. In the case of new contraceptives, that belief is qualified by factors whose effects are economic and whose causes are several and complex. This is a major dilemma.

The present chapter explores this dilemma from several perspectives. The first is a qualitative look at present market demand as expressed in overall patterns of contraceptive use, worldwide and in the United States.

The second focus is on specific areas of contraceptive need that seem most readily translatable into market demand, that is, ''niches" that are either empty or quite inadequately filled. The indicators of these niches include the various limitations in the current array of contraceptives as expressed in the side effects experienced by users, failure and discontinuation rates reflecting side effects and

other constraints to adoption and continued use, and sterilization as a contraceptive option that is not always appropriate. This focus also encompasses the implications of the sexually transmitted diseases for contraceptive technology and their relevance for the contraceptive market.

The third perspective has to do with consumer preferences, with particular attention to the content and character of the "woman-centered agenda" and the issues it raises.

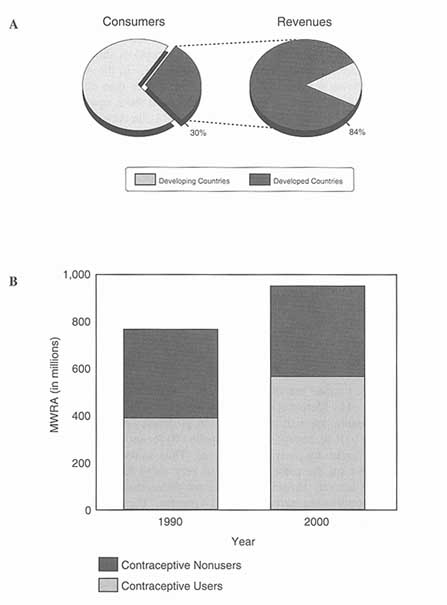

The fourth perspective is quantitative: a look at today's market for contraceptives in terms of numbers of actual and potential users and dollar values; lessons to be learned from the world vaccine market, with which the contraceptives market is in some ways analogous; and subsidized procurement as a market factor.

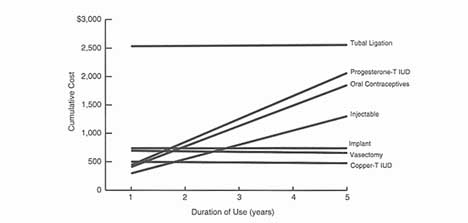

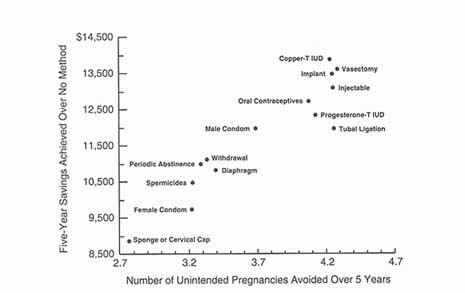

The chapter closes with a discussion of the cost-effectiveness of contraception and what that might mean as an incentive to investment in contraceptive R&D and the intimate and necessary relationship of that investment with the market for contraceptive technologies.

Current Contraceptive Use

Contraceptive Use Worldwide

Contraceptive prevalence2 among women currently married or in union (a group designated by the abbreviation MWRA, or "married women of reproductive age") increased worldwide from 30 percent during 1960-1965 to 57 percent in 1990. The increase was much more dramatic in the developing countries, where prevalence rose from 9 percent to 53 percent in that same period (UN 1994, cited in WHO/HRP 1995). The increase was especially dramatic in eastern Asia and Latin America, slightly less so in other parts of Asia and in North Africa, least of all in Sub-Saharan Africa. The range is wide: Contraceptive use prevalence in Africa is currently estimated at 17 percent, quite a difference from Latin America, for example, where prevalence is almost 65 percent (see Table 5-1 and Table 5-2 for data for developing countries).

There is also great variability within regions. While overall prevalence in the Arab States and Europe averages 44 percent, the range is from almost zero in some Persian Gulf countries to 68 percent in Turkey. And, in Asia, where the overall prevalence is 62.5 percent, the range is from 10 percent in Afghanistan to a use prevalence of 80 percent or more in China. Variability in contraceptive use prevalence among the industrial countries is much narrower (Guttmacher Institute 1995a; WHO/HRP 1995).

The overwhelming majority—90 percent-—of women using contraception in the developing countries are using modern methods. Globally, the most used method is female sterilization (tubectomy or tubal ligation). Thirty percent of all contracepting couples worldwide relied on female sterilization as of 1990; in the

TABLE 5-1 Basic Data, Total Population, and Contraceptive Use, World and Developing Countries, 1994 and Projected for 2005 (in thousands)

|

|

1994 |

2005 |

|

|

World |

|

|

Total population |

5,646,200 |

6,665,120 |

|

Total female population |

2,803,790 |

3,307,980 |

|

Women of reproductive age (aged 15-49) |

1,415,810 |

1,681,040 |

|

Women of reproductive age, married or in union (MWRA)a |

976,728 |

1,145,490 |

|

Contraceptive users among all women |

595,103 |

755,817 |

|

|

Developing Countries |

|

|

Total population |

4,418,180 |

5,364,550 |

|

Total female population |

2,172,230 |

2,642,990 |

|

Women of reproductive age (aged 15-49) |

1,106,570 |

1,368,950 |

|

Women of reproductive age, married or in union (MWRA)a |

784,897 |

953,815 |

|

Contraceptive users among all women |

457,759 |

625,521 |

|

Contraceptive users among married/in union women |

445,692 |

602,417 |

|

a MWRA = married women of reproductive age, defined as "married or living with a man," vis-à-vis "now widowed, divorced, or no longer living together." Source: United Nations Population Fund. Contraceptive Use and Commodity Costs in Developing Countries, 1994-2005. New York, 1995. Data for total population are from the United Nations 1992 estimates and projections. User data are derived from sample surveys carried out in 69 developing countries in the 1980s and 1990s; these countries contained 90 percent of the population and 94 percent of contraceptive users of all developing countries in 1990. Contraceptive prevalence for the period of analysis was projected using a demographic approach that takes the level of contraceptive prevalence as estimated from the latest national survey and then projects increases in contraceptive prevalence as a function of estimated changes in total fertility rates. The basis is the United Nations medium population projection. These rates are then applied to the number of MWRA and unmarried women who use contraception; the fact that there are now data from 34 countries for this second population group makes its inclusion in global calculations of contraceptive prevalence possible for the first time. |

||

TABLE 5-2 Number of Contraceptive Users, by Method, World and Developing Countries, 1994 and Projected for 2005 (in thousands)

|

|

|

Sterilization |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

|

|

|

All |

Female |

Male |

Pill |

Injectable |

IUD |

Condom |

Other |

Users |

|

|

|

|

|

|

World |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1994 |

233,597 |

183,323 |

50,274 |

92,060 |

11,879 |

127,156 |

51,451 |

78,960 |

595,103 |

|

|

2005 |

290,599 |

232,514 |

58,085 |

120,097 |

9,375 |

152,325 |

58,965 |

4,456 |

755,817 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Developing Countries |

|

|

|

|

||

|

1994 |

200,149 |

161,107 |

39,042 |

51,352 |

10,461 |

112,115 |

24,778 |

46,837 |

445,692 |

|

|

2005 |

258,847 |

210,031 |

48,816 |

76,603 |

17,058 |

137,079 |

35,702 |

77,128 |

602,417 |

|

|

Source: United Nations Population Fund. Contraceptive Use and Commodity Costs in Developing Countries, 1994-2005. New York, 1995. Data are derived from sample surveys carried out in 69 developing countries in the 1980s and 1990s; these countries contained 90 percent of the population and 94 percent of contraceptive users of all developing countries in 1990. Contraceptive prevalence for the period of analysis was projected using a demographic approach that takes the level of contraceptive prevalence as estimated from the latest national survey and then projects increases in contraceptive prevalence as a function of estimated changes in total fertility rates. The basis is the United Nations medium population projection. These rates are subsequently applied both to the number of MWRA (married women of reproductive age) and to the number of unmarried women who use contraception; the fact that there are now data from 34 countries for this second population group makes its inclusion in global calculations of contraceptive prevalence possible for the first time. |

||||||||||

developing countries, that figure was 38 percent (UNFPA 1994; WHO/HRP 1995). As for reversible methods, the IUD is the second most used method in the developing countries, primarily because of its extensive use in the People's Republic of China; it ranks fourth in the industrial economies, a ranking that might be higher were it not for the unavailability of the IUD in most of eastern Europe and its very limited use in the United States. The pill ranks third in the developing countries and is the most prevalent method in the industrial countries. The condom fails to even approach the levels of utilization in the developing countries that it has achieved elsewhere. In fact, all coitus-related methods (condoms, vaginal methods, withdrawal) are far less likely to be used in most developing countries than in the industrial countries. Because Norplant is so new and available in very few developing countries, use prevalence data are not included in the tables below. As of 1993, there were an estimated 1.5 million users of that method in developing countries (of whom 1.3 million were in Indonesia), with an admittedly arbitrary estimate of 6.8 million by 2005 (UNFPA 1994). It is important to remember that any ranking of method utilization reflects only what people do, not necessarily what they prefer; in much of the developing world, the full "mix" of methods that would permit individuals to truly express preference by choosing among real options is not generally available (WHO/HRP 1995) (see Table 5-3 and Table 5-4).

Contraceptive Use in the United States

In 1988, over two-thirds of women of reproductive age in the United States were at risk of unintended pregnancy, that is, they were sexually active and did not want to become pregnant but would be physically able to become pregnant if they or their partner used no contraceptive method (Forrest 1994b). Of those 39 million women, 35 million (9 in 10) were using a contraceptive and 4 million were not (Forrest 1994b).

Key problems in the use of reversible contraception in the United States and elsewhere are the high rates of discontinuation of use by 12 months after initiation and the number of unintended pregnancies among women who state that they or their partners were regularly using a method of contraception.

There is also evidence of unrealistic expectations regarding contraceptive use. This, in very small part, is due to side effects unidentified in premarketing clinical trials. In addition, known side effects are not taken into account appropriately in prescribing practice or the product information materials are so fully detailed that they are not read or fully understood (Carpenter 1989; Forrest 1994a). Further, the fact that contraceptives are used by theoretically healthy individuals who are not seeking prevention or cure, as those are medically understood, conditions the extent to which users are willing to make trade-offs, even when the costs of a potential pregnancy may be very high. The combination of all these factors with the unfettered litigiousness that characterizes the contemporary

American scene results in a distinctive and difficult environment in the United States.

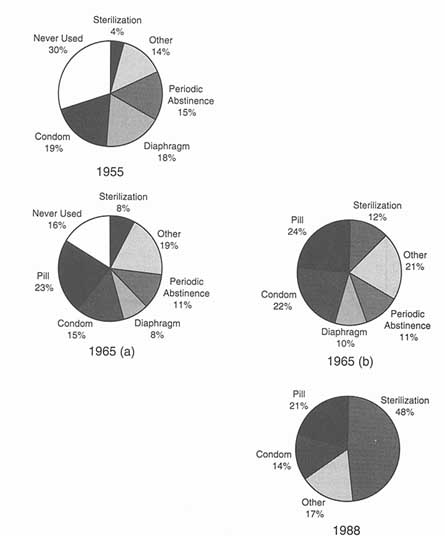

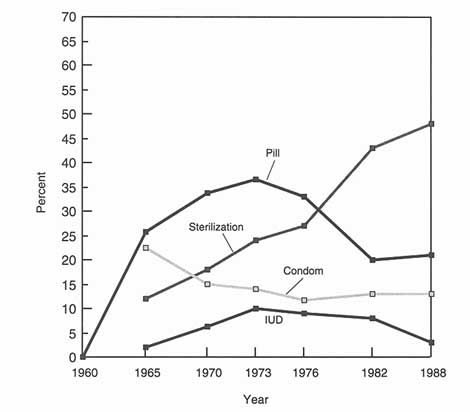

Figure 5-1 presents the proportionate use of each principal contraceptive method in the United States in 1955, 1965, and 1988. Figure 5-2 presents a more detailed picture of shifts in that trajectory between 1960 and 1988. Figure 5-2 makes clear what is sometimes forgotten, that is, that the picture in 1955 in the United States was far from being a blank slate: Among currently married white women aged 18-39 in that year, 70 percent had used contraception at some point and 34 percent had used a method before their first pregnancy. Nonetheless, what was available for use was quite limited, in variety and efficacy, and either coitus-dependent (condom, diaphragm, douche, withdrawal, spermicides) or linked to the timing of coitus (periodic abstinence); only 4 percent of U.S. women had been sterilized for contraceptive purposes.

The broad pattern changes since the availability of oral contraceptives beginning in 1960 have been:

- Increase in total contraceptive use and pill use between 1955 and 1965 and decreased use of the diaphragm, condom, and periodic abstinence.

- Steep increase in interest in coitus-independent methods and in method efficacy.

- Increased reliance on female-controlled methods, especially in the 1960s.

- Steady growth in resort to contraceptive sterilization since the mid- 1960s.

- Increased IUD use from the early 1960s till the early 1970s, then a sharp decrease to a stable but low plateau in the late 1980s.

- Decline in condom use in the early 1960s and 1970s, then increase in the 1980s.

- Rapid adoption of new methods—pill, Today sponge, injections, Norplant—as each appeared, with diminished utilization as side effects were experienced.

In addition to these larger patterns, there have been smaller patterns in contraceptive method use that have been dictated by differences and changes in the circumstances of women's lives. The result is a profile of how various female subpopulations tend to adopt or reject certain methods over time (see Table 5-5).

Specific Needs and Market Opportunities: The Limitations of Available Contraceptives

Side Effects

Like any medical intervention, all contraceptive methods have side effects. Some of those can be life threatening when a method is prescribed inappropriately for women for whom it is medically contraindicated or when an infection

TABLE 5-3 Contraceptive Use Among Married/in Union Women, by Method, and Region, 1994 (in thousands)

|

|

Africa |

Arab States and Europe |

Asia and Pacific |

|||

|

Method |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

Sterilization |

1,625 |

11.8 |

1,057 |

5.3 |

179,318 |

49.2 |

|

Female |

1,541 |

11.2 |

1,030 |

5.2 |

140,905 |

38.7 |

|

Male |

84 |

0.6 |

27 |

0.1 |

38,413 |

10.5 |

|

Pill |

3,507 |

25.5 |

6,081 |

30.7 |

28,579 |

7.8 |

|

Injectable |

1,748 |

12.7 |

146 |

0.7 |

7,559 |

2.1 |

|

IUD |

1,145 |

8.3 |

5,461 |

27.6 |

100,205 |

27.5 |

|

Condom |

512 |

3.7 |

1,225 |

6.2 |

21,076 |

5.8 |

|

Othera |

5,240 |

38.0 |

5,818 |

29.4 |

27,545 |

7.6 |

|

Otherc |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Total |

13,777 |

100.0 |

19,791 |

100.0 |

364,282 |

100.0 |

|

Note:—= no data available. a Data for Africa designate as "Other" vaginal methods, Norplant, and traditional methods. In the U.S. National Survey of Family Growth, "Other" included jellies and creams, suppositories and inserts, the Today sponge, douche, diaphragm, foam, periodic abstinence, and withdrawal. b No implants were available in the United States at the time these data were gathered. c 'This category includes data on users as follows: diaphragm, 2 million/5.7 percent; periodic abstinence, 0.8 million/2.3 percent; withdrawal, 0.8 million/2.2 percent; spermicides, 0.6 million/1.8 percent; sponge, 0.4 million/l. percent. Source: For all data except for the United States, United Nations Population Fund. Contraceptive Use and Commodity Costs in Developing Countries, 1994-2005 (Technical Report No. 18). New York, 1994. For the U.S. data, National Center for Health Statistics, 1988 National Survey of Family Growth, cited in Alan Guttmacher Institute, Facts in Brief: Contraceptive Use. New York, March 1993. |

||||||

results from an associated surgical intervention (Carpenter 1989; Hatcher et al. 1994). Nonetheless, while not negligible, the mortality attributable to contraceptive use is very small. For the most part, women's concerns about the contraceptive technologies that are currently available have to do with side effects that are distressing or annoying in themselves or that lead women to conclude that something bad may be going on in their bodies. These side effects include nausea, headaches, and weight gain due to the pill; increased bleeding, dysmenorrhea, and expulsion associated with the IUD; menstrual changes from implants and injectables; and the irreversibility of sterilization. These will vary among individuals according to severity, cultural meaning, and the extent to which they impinge on the ability to live life. Other health-related considerations have to do

|

|

Latin America and Caribbean |

Total Developing Countries |

USA (1988) |

|||

|

Method |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

No. |

% |

|

Sterilization |

18,148 |

37.9 |

200,149 |

44.9 |

13,686 |

39.2 |

|

Female |

17,631 |

36.9 |

161,107 |

36.1 |

9,617 |

27.5 |

|

Male |

517 |

1.1 |

39,042 |

8.8 |

4,069 |

11.7 |

|

Pill |

13,183 |

27.6 |

51,352 |

11.5 |

10,734 |

30.7 |

|

Injectable |

1,008 |

2.1 |

10,461 |

2.3 |

—b |

— |

|

IUD |

5,303 |

11.1 |

112,115 |

25.2 |

703 |

2.0 |

|

Condom |

1,965 |

4.1 |

24,778 |

5.6 |

5,093 |

14.6 |

|

Othera |

8,233 |

17.2 |

46,837 |

10.5 |

76b |

0.6a |

|

Otherc |

— |

— |

— |

— |

4,620 |

13.1 |

|

Total |

47,840 |

100.0 |

445,692 |

100.0 |

34,912 |

100.0 |

|

Note:—= no data available a Data for Africa designate as "Other" vaginal methods, Norplant, and traditional methods. In the U.S. National Survey of Family Growth, "Other" included jellies and creams, suppositories and inserts, the Today sponge, douche, diaphragm, foam, periodic abstinence, and withdrawal. b No implants were available in the United States at the time these data were gathered. c 'This category includes data on users as follows: diaphragm, 2 million/5.7 percent; periodic abstinence, 0.8 million/2.3 percent; withdrawal, 0.8 million/2.2 percent; spermicides, 0.6 million/1.8 percent; sponge, 0.4 million/l. percent. Source: For all data except for the United States, United Nations Population Fund. Contraceptive Use and Commodity Costs in Developing Countries, 1994-2005 (Technical Report No. 18). New York, 1994. For the U.S. data, National Center for Health Statistics, 1988 National Survey of Family Growth, cited in Alan Guttmacher Institute, Facts in Brief: Contraceptive Use. New York, March 1993. |

||||||

with method qualities that produce difficulty, such as manipulation of the genitals; associated physical exams; fear of surgery, loss of potency, or diminution of libido; and random myths (Bongaarts and Bruce 1995). Table 5-6 presents the risks and side effects of currently available contraceptive methods; it also presents their noncontraceptive benefits.

Developing Countries

An extensive review of published and unpublished studies of contraceptive utilization in the developing world indicates that one in every five women with an unmet need for contraception is not using a modern contraceptive method, owing

TABLE 5-4 Contraceptive Usage, Method Rankings, Selected Regions and Countries

|

Total Developing World (1994) |

Africa |

Arab States and Europe |

Asian and Pacific |

Latin America and Caribbean |

More Developed Regionsa |

USA (1988) |

USA (1995) |

|

Tubectomy |

Other |

Pill |

Tubectomy |

Tubectomy |

Pill |

Pill |

Pill |

|

IUD |

Pill |

Other |

IUD |

Pill |

Condom |

Tubectomy |

Tubectomy |

|

Pill |

Injectable |

IUD |

Vasectomy |

Other |

Tubectomy |

Condom |

Condom |

|

Otherb |

Tubectomy |

Condom |

Pill |

IUD |

IUD |

Vasectomy |

Periodic abstinence |

|

Vasectomy |

IUD |

Tubectomy |

Otherc |

Condom |

|

Otherc |

Injectabled |

|

Condom |

Condom |

Injectable |

Condom |

Injectable |

|

Diaphragm |

Diaphragm |

|

Injectable |

Vasectomy |

Vasectomy |

Injectable |

Vasectomy |

|

IUD |

IUD |

|

Note: Tubectomy = tubal litigation. a Northern America, Japan, Europe, Australia/New Zealand, former USSR. b "Other" here includes vaginal methods, Norplant, and traditional methods. c "Other" includes vaginal methods, periodic abstinence, and withdrawal. d Depo-Provera. Sources: United Nations Population Fund. Contraceptive Use and Community Costs in Developing Countries 1991-2005. Technical Report No. 18. New York, 1994. Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation. 1995, 1993, and 1991 Annual Birth Control Studies. Raritan, NJ, 1995. Shah IH. The advance of the contraceptive revolution. Health Statistics Quarterly 47(1):9-15. 1994. |

|||||||

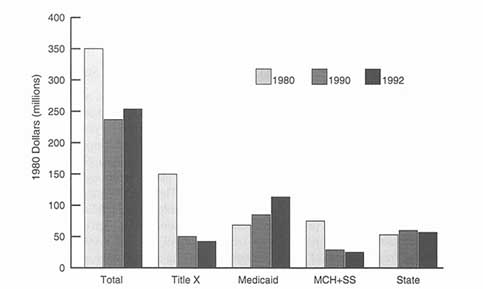

Figure 5-2

Trajectory of change in method use, United States, 1960-1988.

Source: Adapted from JD Forrest. Contraceptive Use in the United States: Past, present, and future. Advances in Population 2:29-48, 1994.

to poor or absent access to services, perception of side effects, or health concerns associated with modern contraceptives (WHO/HRP 1995). Health concerns, sometimes deriving from lack of clear understanding about the method and its side effects—are by far the most important single reason for nonadoption and, in most countries, are more frequently reported than all other concerns combined. Access in many rural settings is also a major problem. The principal foci of concern are the pill, the IUD, and sterilization. Among women with health concerns, contraceptive prevalence is reduced by an average of 86 percent for the IUD, 71 percent for the pill, and 52 percent for sterilization (Bongaarts and Bruce 1995).

This does not mean that other factors do not matter, only that they may be somehow qualified or cannot be documented as quantitatively significant. For

TABLE 5-5 Contraceptive User Characteristics, U.S. Women, 1988 and 1995, by Method

|

Method |

User Characteristics (1988) |

User Characteristics (1995) |

|

Tubal ligation |

Women 30-44; increased use among formerly married, black and Hispanic women, less educated and lowestincome women |

More married women between 35 and 50 with 2 or more children and higher incomes |

|

Vasectomy |

Currently married women, white women relying on partner |

No change identified. |

|

Pill |

Women under 25, unmarried women, women who intend to have children; increased use among better educated women, among whites, and among those with higher incomes; declines only among teenagers |

Increasing use of low-dose pills lesser extent, by women over 40 by women in their 30s and, to |

|

Condom |

Somewhat increased use, sharp increase among teenagers, unmarried and never-married women |

Increasing use by women over 40 |

|

Diaphragm |

White, college educated, and never-married women who intend to have children; slight decline overall, sharp decline among unmarried women and women under age 30 |

Use now highest between ages 25 and 40 (mainly between ages 30 and 35), women with college and postgraduate degrees; longer use |

|

IUD |

Women who intend to have no more children, previously married women, Hispanic women, those with less education; overall decline, especially among women 25-34, formerly married and less educated, sharpest decline among Hispanic women. |

More women in 30s and 40s with at least one child, in married/ mutually monogamous relationship |

|

Sources: For 1988, Alan Guttmacher Institute. Facts in Brief: Contraceptive Use. New York: The Alan Guttmacher Institute, March 1993. For 1995, Ortho Pharmaceutical Corporation, Executive Summary: 1995 Ortho Annual Birth Control Study. Raritan, NJ, 1995. |

||

TABLE 5-6 Risks, Side Effects, and Noncontraceptive Benefits of Contraceptive Methods

|

Method |

Noncontraceptive Benefits |

Risks |

Side Effects |

|

Implantable contraceptives |

May protect against acute PID, ovarian and endometrial cancers; lactation undisturbed; may decrease menstrual blood loss and pain; suppression of pain associated with ovulation |

Infection at implant site; difficult removal; not protective against viral STDs, including HIV/AIDS |

Tenderness at implant site, menstrual cycle disturbance (amenorrhea becomes less common over time), weight gain, breast tenderness, headaches, ovarian enlargement, dizziness, nausea, acne, dermatitis, hair loss |

|

Injectable contraceptives |

May protect against PID, ovarian cancer, and endometrial cancers; decreased menstrual blood loss and risk of anemia; decreased menstrual pain; suppression of pain associated with ovulation; decreased frequency of seizures |

Decreased bone density; not protective against viral STDs, including HIV/AIDS |

Menstrual cycle disturbance (amenorrhea becomes more common over time), weight gain, breast tenderness, depression, delay in return of fertility, decreased HDL cholesterol levels, headaches |

|

IUDs |

None known; progestin-releasing IUDs may decrease menstrual blood loss and pain |

Slight increase in risk of PID in first 20 days after insertion; perforation of the uterus, anemia; not protective against viral STDs, including HIV/AIDS |

Menstrual cramping, spotting, increased bleeding |

|

Oral contraceptives |

Protects against acute infection of the fallopian tubes (PID), ovarian and endometrial cancers, benign breast masses, ovarian cysts; decreased ectopic pregnancy; decreased menstrual blood loss and risk of anemia; decreased menstrual pain, suppression of pain associated with ovulation |

Estrogen-associated: slight increase in blood clot complications, stroke, liver tumors, hypertension, heart attacks, cervical erosion or ectopia, cervical chlamydia Progestin-associated: diabetesrelated changes, hypertension, heart attacks |

Estrogen-associated: nausea, headaches, fluid retention, weight gain, increased breast size, breast tenderness, stimulation of breast tumors, watery vaginal discharge, rise in cholesterol concentration in gallbladder bile, uterine fibroids |

|

Method |

Noncontraceptive Benefits |

Risks |

Side Effects |

|

Oral contraceptives |

|

Associated with increased cervical chlamydia; not protective against viral STDs, including HIV/AIDS |

Progestin-associated: weight gain, depression, fatigue, headaches, decreased libido, acne, increased breast size, breast tenderness, increased LDL cholesterol level, decreased HDL cholesterol level, chronic itch |

|

Male condoms |

Protects against bacterial and viral STDs, including HIV/AIDS; delays premature ejaculation; erection enhancement; prevention of sperm allergy |

None known |

Decreased sensation during intercourse, allergy to latex, possible interference with erection, loss of spontaneity |

|

Female condoms |

Protects against STDs, including HIV/AIDS, including on the vulva |

None known |

Decreased sensation during intercourse, allergy to polyurethane; aesthetically unappealing and awkward to use for some |

|

Barrier methods (diaphragm, cervical cap, sponge) |

Protects against bacterial STDs, prevention against HIV/AIDS not proven; diaphragm protects against cervical infection and neoplasia |

Vaginal trauma, toxic shock syndrome (rare), cervical erosion |

Vaginal and urinary tract infection (anaerobic overgrowth); vaginal discharge if not removed appropriately; allergy to spermicide, rubber, or latex; pelvic pressure, bladder or rectal pain; penile pain |

|

Method |

Noncontraceptive Benefits |

Risks |

Side Effects |

|

Spermicides |

Spermicides with nonoxynol-9 protect against gonorrhea and chlamydia: prevention against viral STDs, including HIV/AIDS, undetermined |

None proven; however, tissue irritation may enhance susceptibility to HIV infection |

Tissue irritation, yeast vaginitis, allergy to spermicidal agents Note: STDs = sexually transmitted diseases; PID = pelvic inflammatory disease. |

|

Sources: Institute of Medicine. The Best Intentions: Unintended Pregnancy and the Well-Being of Children and Families. S Brown, L Eisenberg, eds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. 1995. Ehrhardt AA, JN Wasserheit. Age, gender, and sexual risk behaviors for sexually transmitted diseases in the United States. IN Research Issues in Human Behavior and Sexually Transmitted Diseases in the AIDS Era. JN Wasserheit, SO Aral, KK Holmes, PJ Hitchcock, eds. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology. 1991. Hatcher RA, J Trussell, F Stewart, et al. Contraceptive Technology, 16th Revised Edition. New York: Irvington Publishers, 1994. |

|||

example, even in areas where high fertility norms persist, birth spacing is considered highly desirable; the quintessential case is Sub-Saharan Africa. Another example is the weight of male disapproval of family planning. Evidence from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and studies of fertility decision making suggests that this may either be changing in some settings or may be overstated. Women often assume the existence of male opposition simply because they are afraid to raise the topic with their partners, a reflection of very fundamental issues of power and control (Bongaarts and Bruce 1995; WHO/HRP 1995).

The United States

Research in the United States consistently reports significant lack of the kind of information among adults and adolescents that would allow them to perhaps more fully appraise the relative risks and benefits of contraception. As in the developing world, that limitation affects method adoption and continuation (Forrest 1994b; Institute of Medicine 1995).

The example of oral contraceptives (OCs), on the market for more than 35 years and used by 10 million American women, is informative. A 1993 poll commissioned by the Association for Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) found that 54 percent of their sample of American women believed that there were ''substantial risks" (mainly cancer) associated with oral contraceptives (Gallup Organization 1994). Relatively few women knew the several noncontraceptive benefits of the pill and 42 percent believed there to be no health benefits from pill use other than pregnancy prevention. Only 6 percent were aware that the pill is actually protective against cancer; in fact, in the 1993 survey and an earlier ACOG survey in 1985, the same proportions of women—one-third—cited cancer as the chief risk of using oral contraceptives (Gallup Organization 1994). In both the 1985 and 1993 surveys, better than two-thirds of the sample incorrectly believed that OC use was more risky or as risky as childbirth, even though the opposite is true (Gallup Organization 1994).

A telephone poll of 1,000 American women, conducted for the Kaiser Family Foundation in 1995, found that only one-quarter of women of reproductive age are confident that oral contraceptives are "very safe" for the user; others expressed a spectrum of concern, with 43 percent considering them "somewhat safe," 18 percent "somewhat unsafe," and 11 percent "very unsafe." Six out of 10 of these women cited worries about potential health risks, while many others expressed concern that the pill does not protect against sexually transmitted diseases or that it is ineffective in preventing pregnancy. One-third incorrectly thought that oral contraceptives increased the risk of ovarian cancer and 40 percent said there was no effect; only 16 percent correctly said that the pill actually reduces that particular risk (Russell 1996).

Part of the problem is the likelihood of inadequate provider-client commu-

nication. For instance, a random-sample, telephone survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation and Louis Harris & Associates in October-November 1994 found that most American women with the potential of experiencing an unplanned pregnancy are uninformed or misinformed about the "morning-after" pill, an emergency contraceptive option currently available off label in the United States that can prevent a potential pregnancy up to 72 hours after unprotected sex (Kaiser/Harris 1995).3 A separate survey found that while 78 percent of U.S. obstetrician-gynecologists in the United States are very familiar with emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs), another 22 percent are somewhat familiar with them, and 72 percent of the entire sample consider the method both safe and effective, most have prescribed it only for a handful of their patients within the last year (Kaiser/Fact Finders 1994). Thus, only one-third of women polled indicated that they knew that anything could be done after unprotected sex to prevent pregnancy and half of those who do know are misinformed about proper timing. The difficulty seems to be that, in general, clinicians make their female patients aware of ECPs in response to an emergency situation rather than during routine contraceptive counseling; when women do call in, they may well encounter receptionists who do not know about emergency contraception (Kaiser/Harris 1995).

Many clinicians also retain negative perceptions of the IUD dating back to the Dalkon Shield disaster, even though new configurations and formulations make IUDs excellent options for many women (Westoff et al. 1992). Adolescents are especially compromised by their low level of information about contraceptives, tied up as it is in their substantial ignorance about sexuality, fertility, and sexual health. This, in turn, impinges negatively on health-seeking and family planning behavior, though lack of information is far from the only factor (Zabin et al. 1991). Nevertheless, the disposition of some U.S. media to overstate modest risks and understate the major health and social benefits of contraception does little to enhance thoughtful decision making about contraceptive use. The adverse and unbalanced media coverage of Norplant motivated women who were experiencing no problems to seek removal and, in undetermined degree, fueled a litigation "explosion" noted in the media themselves (Economist 1995; Herman 1994; Kolata 1995).

At the same time, there are unresolved uncertainties that make the use of certain methods inappropriate for some women and, in some cases, for rather large groups of women. The IUD for women with an active, recent, or recurrent pelvic infection or for women at high risk for a sexually transmitted disease is inappropriate. The jury is still out in connection with a slight increase in breast cancer risk among younger users of oral contraceptives, even though lifetime increased risk is close to zero. Nor are oral contraceptives or Norplant advisable for women with significant cardiovascular risk profiles, particularly in women over 35 (Hatcher et al. 1994). In a discussion later in this report of "informed choice," the point is made that prescribing any contraceptive method to women for whom it is contraindicated is patently a great disservice to them; it is also a

great disservice to the reputation of the technologies themselves. However, overall, modern hormonal and intrauterine contraceptives are extremely safe in comparison to the risks of pregnancy, a fact that is poorly understood.

Contraceptive Failure and Discontinuation

Contraceptive effectiveness, failure, continuation, and discontinuation are intimately linked since they are, in important respects, functions of one another. The likelihood that a contraceptive will fail to protect the user depends primarily on two factors. The first is the inherent efficacy of the method itself when used properly (perfect use); this includes technical attributes that make a method easy or difficult to use. The second factor has to do with the characteristics of the user: how often the method is used correctly and consistently, frequency of intercourse, and age (Hatcher et al. 1994).

An example: Although combination oral contraceptives have a perfect-use pregnancy rate of 0.1 percent during the first year of use, the typical-use pregnancy rate is closer to 3 percent (Hatcher et al. 1994) because, as with many medications, compliance with daily pill use is difficult for many women. A far more extreme example is the ovulation method of periodic abstinence, with first-year probabilities of failure of 3 percent during perfect use but as high as 86 percent during imperfect use (Trussell and Grummer-Strawn 1990).

In thinking about the need for new contraceptives, it is important to remember that the majority of today's reversible methods are hard to use perfectly all the time. How consistently the method is used correctly reflects both the user's skill and determination—or lack of them—as well as the inherent complexity and limitations of the methods themselves (Institute of Medicine 1995). It is also important to remember that the components of "determination" reflect some sort of internal balancing of benefits and burdens (Bulatao and Lee 1983), some personal calculus of choice (Zabin 1994), that is, in most individuals in varying measure, a labile blend of immediate and more distant circumstances and pressures, personality, attitudes, feelings, beliefs, motivation, and ambivalence that may well defy the individual's own explanatory powers (Maynard 1994). The complexity of this subject is reflected in a rich literature covering at least two decades of attempts at understanding; it is also reflected in the incompleteness of that literature, which leaves major age groups and populations almost unexamined (Institute of Medicine 1995). Nonetheless, whatever the determinants, the costs of contraceptive failure are the high rates of abortion and unintended and unwanted pregnancy among women using some reversible methods, particularly those that are coitus-related.

Developing Countries

Analysis of DHS data from 11 developing countries4 found high discon-

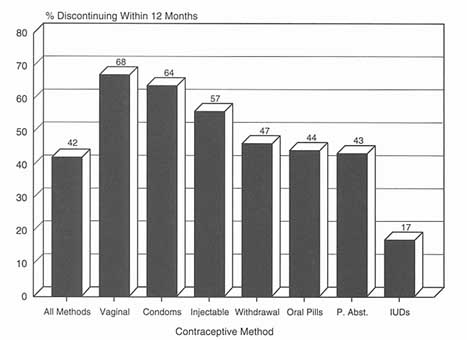

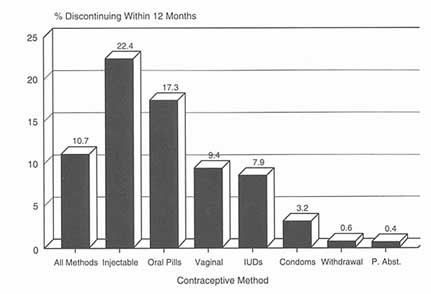

Figure 5-3

Cumulative percentage discontinuing a contraceptive method by 12 months, average for 11 developing countries. P. Abst. = periodic abstinence.

Source: WHO. Perspectives on Methods of Fertility Regulation: Setting a Research Agenda (Background Paper). Geneva: UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank/HRP. 1995.

tinuation rates for all reversible contraceptive methods over the five-year period prior to survey. Rates reflected either dissatisfaction with the method itself or with the service providing it. In the countries studied, average use of any method other than the IUD was under 15 months. Forty-two percent of all contraceptive use was terminated by the twelfth month after adoption, 11 percent because of contraceptive failure (unintended pregnancy), and 11 percent for health concerns and side effects. Overall, 68 percent of users of vaginal methods 5 and 64 percent of condom users discontinued their use by the end of the first year (see Figure 5-3). Discontinuation rates varied by country and method, from a low of 25 percent in Indonesia to a high of 65 percent in the Dominican Republic (a country where 70 percent of users are, in fact, sterilized). Failure rates for condoms and periodic abstinence were similar to typical-use rates estimated for the United States (Trussell and Kost 1987), and failure associated with the IUD was even lower in the 11 developing countries than in the United States; failure rates for the pill, vaginal methods, and withdrawal were significantly higher, however. Not surprisingly, method failures, particularly the failure of traditional methods, resulted

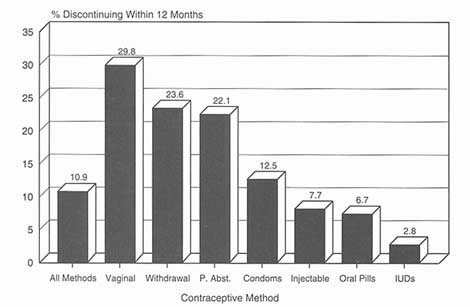

Figure 5-4

Cumulative percentage discontinuing by 12 months due to contraceptive failure, average for 11 developing countries. P. Abst. = periodic abstinence.

Source: WHO. Perspectives on Methods of Fertility Regulation: Setting a Research Agenda (Background Paper). Geneva: UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank/HRP. 1995.

in high rates of unintended pregnancy, often leading to induced abortions (WHO/ HRP 1995). This is, nonetheless, somewhat misleading: These are method-specific termination rates and many women may, in fact, change to another method, so that the more important figures have to do with continuation to some method.

As for causes of discontinuance, 1 out of 5 users of vaginal methods, periodic abstinence, and withdrawal discontinued the method before the end of the first year because of contraceptive failure; the comparable figure for the pill and injectable was 1 in 14 users (see Figure 5-4). Health concerns were the reason for discontinuance for about 1 in 5 users of the pill and injectable, but were of little consequence for users of vaginal methods, periodic abstinence, and withdrawal (see Figure 5-5). Figure 5-6 summarizes these two factors and their contribution to method discontinuance.

In the first month after discontinuation, of the 58 percent of women who discontinued contraceptive use in the four Latin American countries 6 in the sample, 16 percent became pregnant or wanted to do so, 15 percent changed to another modern method, 8 percent changed to a traditional method, and 19 percent abandoned contraception altogether even though they did not want to be-

Figure 5-5

Cumulative percentage discontinuing by 12 months due to side effects and health concerns, average for 11 developing countries. P. Abst. = periodic abstinence.

Source: WHO. Perspectives on Methods of Fertility Regulation: Setting a Research Agenda (Background Paper). Geneva: UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank/HRP. 1995.

come pregnant. The IUD had the lowest discontinuation rate (17 percent) and was judged favorably with regard to both method failure and health concerns compared to other modern reversible methods. In general, there is much variability in contraceptive behavior following method discontinuation, by method and by country. In fact, there is so much variability in terms of preferences relating to future contraceptive use that it is impossible to identify a single method or set of methods as the globally preferred choice of most women. In most countries, while oral contraceptives are the preferred "next method," there is little basis for certainty that any supposedly preferred method would actually be chosen when the decision to adopt it materialized (WHO/HRP 1995).

In sum, perceived or real side effects and health concerns are major factors in the decision to use contraception; for choosing a specific method; for switching; and for abandoning use of modern methods, especially hormonal methods, entirely (WHO/HRP 1995). The totality of these findings is highly relevant to appraising the need for new contraceptive methods. The analysis by the World Health Organization's Human Reproduction Programme (WHO/HRP) concludes:

It is obvious that a substantial number of women will need to switch methods before finding one that suits them, or will need to discontinue use in order to have a pregnancy that they have only been delaying, or will need to switch methods as they make the life course transition from delaying a birth to pre-

Figure 5-6

Summary scattergram of contraceptive methods by percent discontinuing their use within 12 months because of method failure or health concerns.

Source: WHO. Perspectives on Methods of Fertility Regulation: Setting a Research Agenda (Background Paper). Geneva: UNDP/UNFPA/WHO/World Bank/HRP. 1995.

venting a birth. However, they also discontinue or switch because the current state of the available contraceptive methods, especially of hormonal methods, is far from satisfactory. Side-effects and health concerns, [perceived or real], remain major factors in discontinuing the use of hormonal methods, while barrier methods and especially vaginal and traditional methods often lead to accidental pregnancy. For these different reasons, hormonal methods and traditional methods have discontinuation rates that are high and broadly similar. Both the expansion in method mix and the improvement in contraceptive technology appear necessary to increase the satisfaction with the method use and to reduce the incidence of unintended pregnancies because of method failure or abandonment of use by the dissatisfied users (WHO 1995:45).

The United States

Table 5-7 presents failure rates and continuation rates associated with all contraceptive methods under both perfect and typical use for the U.S. population

(Hatcher et al. 1994). As common sense would predict, just as in the 11 developing countries discussed above, method failure is associated with low-efficacy reversible methods, while there are real and imagined health concerns concerning high-efficacy reversible methods, especially those that are least susceptible to user error: implants, IUDs, and injectables. There is also variability within some method categories. For instance, today's oral contraceptives contain much lower doses of estrogen and therefore produce significantly fewer side effects and implications; they also are less forgiving of human error. Failure is also significant in cumulative terms: Current U.S. estimates indicate that the typical woman in the United States will experience one contraceptive failure for every 2.25 live births (Trussell and Vaughn 1989).

As in almost everything else having to do with contraception, there is variation in cause and consequence from subpopulation to subpopulation. Formerly married (separated, divorced, widowed) women have the highest rates of failure in the use of reversible contraceptive methods; married women have the lowest. Women whose incomes are 200 percent or less of the poverty level are twice as likely as higher-income women to have a contraceptive failure, a major contributor to the high concentration of unintended pregnancy in these same groups (Forrest 1994b; Institute of Medicine 1995).

Error rates in pill taking are high and the costs of those error rates are also high. Of the 3.5 million annual unintended pregnancies in the United States, over 1 million are related to OC use, misuse, or discontinuation, with 61 percent of these occurring in women who discontinue OCs. Of that group, 67 percent did not immediately substitute other contraceptives and 33 percent adopted less reliable methods. This is a particularly important consideration for the approximately 3.7 million U.S. women who initiate OC use each year since that group commonly experiences side effects and has a high discontinuation rate. It is also an important consideration in terms of cost: The costs incurred owing to unintended pregnancies in women who discontinue OCs are close to $2.6 billion annually (Rosenberg et al. 1995).7 European women do better yet, even there, 20 percent do not maintain their regimens (Waugh 1994). There was also more failure associated with the less reliable methods; the failure of periodic abstinence rose from 16 to 25 percent during the 1980s and there were slight increases in failure rates for the condom and diaphragm as well (Institute of Medicine 1995).

Another, partially related, source of concern is the high contraceptive failure rate among females under age 20, more than one-quarter of whom experience contraceptive failure during the first 12 months of use, with the lowest-income teens having the highest failure rates. Teens have very poor success with periodic abstinence: 52 percent of low-income teens experience failure, as do 28 percent of higher-income teens (Moore et al. 1995). Younger teens appear to have a

TABLE 5-7 First-year Contraceptive Failures and Continuation Rates, United States

|

|

% of U.S. Women Experiencing Accidental Pregnancy Within the First Year of Use |

|

|

|

Method |

Typical Use |

Perfect Use |

% of U.S. Women Continuing Use at One Year |

|

Chance |

85 |

85 |

|

|

Spermicides |

21 |

6 |

43 |

|

Periodic abstinence |

20 |

|

67 |

|

Calendar method |

|

9 |

|

|

Ovulation method |

|

3 |

|

|

Symptothermal method |

|

2 |

|

|

Postovulation method |

|

1 |

|

|

Withdrawal |

19 |

4 |

|

|

Cap |

|

|

|

|

Parous women |

36 |

26 |

45 |

|

Nulliparous women |

18 |

9 |

58 |

|

Diaphragm |

18 |

6 |

58 |

|

Condom |

|

|

|

|

Female (Reality®) |

21 |

5 |

56 |

|

Male |

12 |

3 |

63 |

|

Pill |

3 |

|

72 |

|

Progestin only |

|

0.5 |

|

|

Combined |

|

0. 1 |

|

|

IUD |

|

|

|

|

Progesterone T |

2.0 |

1.5 |

81 |

|

Copper T 380A |

0.8 |

0.6 |

78 |

|

LNg 20 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

81 |

|

Depo-Provera |

0.3 |

0.3 |

70 |

|

Norplant (6 capsules) |

0.09 |

0.09 |

85 |

|

Female sterilization |

0.4 |

0.4 |

100 |

|

Male sterilization |

0.15 |

0.10 |

100 |

|

Source: Hatcher RA, J Trussell, F Stewart et al. Contraceptive Technology (16th Revised Edition). New York: Irvington Publishers. 1994. |

|||

particularly hard time taking pills properly, though older teens do almost as well as older women in contraceptive use (Guttmacher Institute 1994).

Overall continuation rates in the United States are highest for the high-efficacy, provider-controlled methods (implant, IUD, injectable), followed by the pill. Periodic abstinence and the male condom follow at some distance, with the poorest continuation rates for the low-efficacy, coitus-dependent vaginal methods (diaphragm, spermicides, cervical cap, sponge). There are a number of resemblances between these continuation rates and those in the developing countries analyzed above: When continuation rates are ranked, patterns of use of the IUD, periodic abstinence, pill, condom, and vaginal methods are similar. The major and quite striking difference is continuation with injectables, in this case Depo-Provera (depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate, or DMPA). While the continuation rate for DMPA in the United States is very high, it is low in some developing countries, overwhelmingly because of menstrual-related side effects. The IUD is also interesting in this connection. IUD use rates in the United States, while stable since 1988, are still very low; even prior to the negative sequelae and media coverage of the Dalkon Shield experience, IUD prevalence never surpassed 8 percent, well below the prevalence of the pill or tubal sterilization (Ortho 1991). Nonetheless, while IUD use in the United States is far below that in the developing countries, U.S. women continue to report high satisfaction with the method (Ortho Surveys 1991-1995), just like women in the developing countries.

If there is any global "rule" that can be derived from these reasonably definitive analyses of contraceptive use in developing countries and in the United States, it is that, overall, methods that perform better on the efficacy scale measure poorly on the health concerns scale, and vice versa, at the same time that both safety and efficacy are, in most circumstances, equally valued (WHO/HRP 1995). This rule is consistently expressed despite variation in patterns of contraceptive use, nonuse, and discontinuation; despite the remarkable safety of hormonal contraceptives; and despite such subjective criteria as preferences regarding ease of use, mode and duration of action, and willingness to tolerate the shortcomings inevitably associated with any contraceptive method. On its face, this would seem to be a profound contradiction and what might be called the "contraceptive technology predicament." However, its more subtle meaning may be that, for some women, the more mediated methods (pills and implants, for example) simply arouse greater generic concern than do less mediated ones (barrier methods, for example), even though the latter may be recognized as generally less effective. From this perspective, safety commands first priority, while efficacy may occupy a position further down the scale where "effective enough" is located. The tension between such valuations and the tradeoffs for unobtrusiveness, security, and separation from coitus that are associated with long-acting, provider-dependent methods, is substantial.

Sterilization as a Contraceptive Option

About one in three contraceptive users in the developing world has looked to sterilization as a way of terminating childbearing. There is anecdotal material that reflects user lack of knowledge about the risks and consequences of sterilization and a certain amount of prospective anxiety. While there is evidence of some regret, particularly among women sterilized at younger ages (e.g., in their 20s), there is also satisfaction among many women who have had a tubal sterilization, satisfaction primarily related to the permanence of the method and the problems associated with reversible methods. The method is rightly seen as highly effective and not difficult to ''use"; its safety, as measured in side effects, is defined as "medium," comparable to the IUD, safer than the pill and injectables, but less safe than the low-efficacy vaginal methods and periodic abstinence (WHO/HRP 1995). In considering the primary problems reported for the major contraceptive methods in the Demographic and Health Surveys, 19 percent of the problems reported for sterilization had to do with health concerns, compared to 42 percent for the pill and 35 percent for the IUD (Bongaarts and Bruce 1995).

It is reasonable to view sterilization rates, particularly among younger women and men, as an indicator that other, reversible alternatives are unavailable or unsatisfactory. Nevertheless, as noted earlier, it is only possible to reach this conclusion where options actually exist. In many countries, sterilization is a popular choice; in others, it reflects the fact that there are no other options or that the options that do exist are unappealing because they are difficult to use, because they are unreliable at a time when having no more children has transcendent importance, because users do not like the side effects or because users are simply weary of dealing with them. In countries where a range of options is available (e.g., Colombia, Costa Rica, Iran, Malaysia, Singapore, South Africa, Thailand, and Tunisia in the developing world, and Austria, Canada, and the United States in the developed world), sterilization does reflect choice. In some countries, for example, China and India, sterilization is a preferred method in national or local government programs and rates reflect that emphasis.

Despite an apparently wide range of reversible contraceptive options in the United States, sterilization is nonetheless the most common form of contraception for all racial and income groups (Ingrassia et al. 1995). One reason is that the range of choice is actually narrower than it seems. The typical woman in the United States choosing sterilization is about 30 years old and has two to three children, with 10 to 15 years of fecund life left during which she could become pregnant but does not wish to. When several IUDs were withdrawn from the U.S. market during 1985-1986, leaving only the Progestasert IUD, which had a small group of users, the remaining options for women who could not or would not use the pill formulations then available but wanted a coitus-independent, unobtrusive, and very effective method, were female or male sterilization (Mosher 1990). As noted above, although two IUDs are now available in the United States,8 the

method has a distance to go before it even regains its mid-1970s market share of around 9.5 percent.9

Finally, the promise of Norplant as a most effective alternative (FDA 1995) for women uncertain about terminating fecundity has been checked by adverse press coverage and litigation largely deriving from problems related to implant removal seen only in a small percentage of women. The fact that sterilization is often covered by public or private health insurance is a further incentive for its utilization, especially since insurance coverage for reversible methods is scanty and uneven (Kaeser and Richards 1994).

The core issue in sterilization is its suitability to the stage in the life span when it is-or is not--clear that more children are wanted. Some understandings that are relevant to sterilization appropriateness are emerging from the Collaborative Review of Sterilization, a prospective multicenter study in the United States which has followed 10,000 women undergoing tubal sterilization, each for a minimum of five years, some as long as 10-14 years. Early findings from that study indicate that failure and regret rates are higher than previously thought: 6.9 percent of women sterilized had reported regret during at least one follow-up period and 6.2 percent indicated that they had sought reanastomosis (sterilization reversal) or talked with a health professional about reversal (Wilcox et al. 1990 and 1991). Age at time of sterilization had the most pronounced effect on regret: Women under age 30 were two to three times more likely to report regret than were women aged 30-35, irrespective of parity, marital status, or education. Participants with a history of abortion and those undergoing sterilization concurrent with cesarean section were also at greater risk of regret, as were women receiving public economic assistance (Wilcox et al. 1991).10

Prevalence of Sexually Transmitted Disease , Including HIV/AIDS

There already seems to be a rather loud demand signal in the market "asking" for an industry response to the mounting risk of sexually transmitted disease (STD): Use of dual contraceptive methods, a reasonable indicator of such demand, is on the rise, at least in the United States. In 1979, just 3 percent of respondents reported dual method use; by 1988, respondents in another study reported 16 percent dual use (Plech et al. 1993; Zelnick and Kantner 1980). In the 1988 National Survey of Family Growth, women were asked which methods they used to protect themselves or their partners from infection. Responses to the question revealed that 4.24 million women reported use of the condom as an STD prophylaxis, but did not report use of the condom as a contraceptive. Altogether 10.4 million women of a total of 57.9 women aged 15-44 reported use of condoms for prevention of pregnancy or STDs or both. By the late 1980s, women seeking safer sex were buying 30 to 40 percent of all condoms in the United States (Rinzler 1987).

Since then, tracking of dual use through the annual Ortho Birth Control

Surveys has recorded a steady increase in such use. In 1991, 23 percent of all women and almost 31 percent of unmarried women in the Ortho sample reported altered practices related to STD concerns; in 1994, 46 percent of all surveyed women reported using condoms in addition to their primary contraceptive; by 1995, that figure was 52 percent (Ortho Birth Control Studies 1991, 1993, 1995). Half of those using dual methods reported doing so for STD protection. This would suggest that the other half may have been double-protecting itself against conception; if so, this may reflect perceptions of limited method efficacy and a strong commitment to not becoming pregnant. Whatever the objective, it seems clear that women in the United States are vigorously interested in methods that will protect them against sexually transmitted disease and that there is enough dual use to indicate that many are also vigorously interested in simultaneously protecting themselves from conception. There are a few clues that this is not easy to do: In the couple of instances in the United States where it has been examined, contraceptive decision making and utilization around dual method use appear to be complex and difficult (Kost and Forrest 1992; Landry and Camelo 1994). At the same time, the importance of preventing the sexually transmitted diseases, particularly the viral infections, cannot be overstated, if for no other reason than the fact that once an individual is infected with a viral STD, he or she will henceforth always be infected.

The public health aspects of the resurgence of STDs are addressed in Chapter 2. The purpose of this section is to more precisely quantify that resurgence. A very recent worldwide study by the World Health Organization's Global Programme on AIDS, done in collaboration with the Rockefeller Foundation, discovered the following sobering facts.

Sexually Transmitted Disease Worldwide

At least 333 million new cases of curable sexually transmitted diseases were predicted to occur in the world in 1995. This includes 12 million new cases of syphilis, 62 million new cases of gonorrhea, 89 million new cases of chlamydial infection, and 170 million new cases of trichomoniasis (WHO/GPA 1995). In 1990, using a modified Delphi technique, the WHO estimated that, in that year, there were over 250 million new cases of all sexually transmitted diseases (WHO/ GPA 1995). Thus, this new estimate of 333 million new cases of just four of the STDs—chancroid and the major viral STDs (e.g., herpes, human papillomavirus, and hepatitis B) were not included because of data deficiencies—is a huge increase. Table 5-8 summarizes the prevalence and incidence data for all four diseases for all of the world's regions.

Results of several large studies of human papillomavirus (HPV) and its relation to cervical cancer are also worrisome. It is clear that most, if not all, of the 500,000 cases of cervical cancer worldwide each year are caused by HPV. A 22-country study of HPV prevalence in cervical cancer patients found an overall

TABLE 5-8 Estimated New Cases of the Curable Sexually Transmitted Diseases, All Regions, 1995

|

Region |

Syphilis |

Gonorrhea |

Chlamydiaa |

Trichomoniasis |

Total by Region |

[Chancroid]b |

|

North America |

140,000 |

1.8 million |

4 million |

8 million |

14 million |

|

|

Western Europe |

200,000 |

1.2 million |

5 million |

10 million |

16 million |

|

|

Australasia |

10,000 |

0.13 million |

300,000 |

1 million |

1 million |

|

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

1.3 million |

7.1 million |

10 million |

18 million |

36 million |

|

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

3.5 million |

16 million |

15 million |

30 million |

65 million |

|

|

Northern Africa and the Middle East |

620,000 |

1.5 million |

2.9 million |

4.6 million |

10 million |

|

|

Eastern Europe and Central Asia |

100,000 |

2.3 million |

5 million |

10 million |

18 million |

|

|

East Asia and Pacific |

330,000 |

3 million |

6.2 million |

13 million |

23 million |

|

|

South and Southeast Asia |

5.8 million |

29 million |

40 million |

75 million |

150 million |

|

|

Global Totals |

12 million |

62 million |

89 million |

170 million |

333 million |

[7 million] |

|

a This refers to chlamydia trachomatis in adults. b No estimates could be made for chancroid using the same methodology developed for the other four diseases, since understanding of the epidemiology and natural history of the disease is poor and there is yet no good diagnostic for estimating prevalence and duration of infection. The estimate given here for chancroid is based on the ratio of syphilis to chancroid in the previous WHO (Delphi) estimates for those two diseases and the 1995 estimate for syphilis. Source: World Health Organization. An Overview of Selected Curable Sexually Transmitted Diseases (WHO/GPA/STD/95.1). Geneva: WHO/Global Programme on AIDS, August 1995. |

||||||

rate of 93 percent; it also found that just 4 of the 70 different types of HPV cause 80 percent of all cervical cancer cases, as identified in over 1,000 cervical cancer tumor specimens through use of new DNA techniques (American Health Consultants 1995; Bosch et al. 1995).

Sexually Transmitted Disease in the United States

For the four diseases analyzed by the WHO, the U.S. incidence of 14 million new cases in 1995, with an estimated prevalence of 52 million for 1995, ranks fifth among the nine WHO regions. U.S. prevalence rates are the same as those in Australasia but higher than rates in Western Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and South and Southeast Asia. The U.S. incidence figure is also considerably higher than the estimate of 12 million new cases annually for all STDs in the United States that is commonly used (CDC 1990, cited in Rosenberg et al. 1992). The 1988 data indicated that three-quarters of all STDs in the United States were accounted for by three diseases: chlamydia (4 million cases), trichomoniasis (3 million), and gonorrhea (1.8 million).

Rates of infection in the United States vary by age and ethnicity. Among women attending family planning clinics from 1989 to 1993, chlamydia infection rates were 4.5 percent (whites), 5.5 percent (Hispanics), and 8.5 percent (African-Americans) (WHO/GPA 1995). Most worrisome is the fact that, in the United States, STD incidence increased rapidly during the 1960s and 1970s and has stayed at those high levels (Cates 1991). At present, 86 percent of all STDs occur among individuals 15 to 29 years old (NARHP 1995), two-thirds among individuals under age 25 (CDC 1992). The Maternal and Child Health Bureau reports that about 3 million U.S. adolescents contract an STD annually. Studies by the Alan Guttmacher Institute have found 15 percent of active teenage women to be infected with HPV; 15- to 19-year-olds also have a 1-in-8 chance of developing pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and sexually active 10- to 14-year-olds are 7 times more likely to have a PID than 20- to 24-year-olds (Guttmacher Institute 1994). Nearly 200,000 cases of gonorrhea were reported among teens in 1989; visits by teenage women to fee-for-service practices for genital herpes infections grew from 15,000 in 1966 to 125,000 in 1989; and the number of visits for genital warts caused by HPV grew from 50,000 in 1966 to 300,000 in 1989, and perhaps three times as many women had asymptomatic cervical HPV infection (Hatcher et al. 1994).

Consumer Perspectives

Consumer Decision Making and Preferences

The market for any product is formed at the intersection of price, product availability, and consumer decisions. In a producer's ideal market, consumers

"vote" for products by making at least an initial commitment through purchase and, best of all, by continued use; in other words, they are predictable and loyal consumers. In a less than ideal market, consumers may be so uninformed about their options, the range of their options may be so limited, and consumer motivations may be so intricate that it is hard to interpret the meaning of initial votes or to anticipate loyalty.

By these definitions, the market for contraceptives is not ideal. Contraceptive decision making is influenced by a welter of motivational factors: method safety11 and effectiveness12; specific personal considerations; and availability, accessibility, and cost. Safety and effectiveness appear to be consistently important (WHO/HRP 1995) although, depending on the situation, there may be willingness to trade off efficacy against other method qualities, especially since side effects are tolerated differently by different women. For instance, in a setting where abortion is legal and safe, a woman' s main concern may not be contraception, but she may be quite concerned about sexual disease transmission. A young woman who was recently divorced but who might want more children in a second marriage may be willing to put up with contraceptive side effects, for instance, changes in menstrual patterns, to avoid the sterilization she does not yet want to have.

In other words, the dominance assigned to each factor in contraceptive decision making will vary by age, relationship status, family size, culture, and circumstance; by perceptions and knowledge about individual methods; by ambivalence about childbearing; by interest in spontaneity and ease of use; and by issues of power and control. The notion of risk cuts across all these variables: risks to health, method failure, getting "caught" using a method when secrecy is desired, investment in a costly method that might not work out, resort to sterilization when one might have a change of heart. All this is projected against the complicated and changing nature of women's reproductive lives, their ability to exercise control over those lives, and by sometimes considerable forces in the larger political and social environment.

There is also the matter of access. In some developing countries and in the former socialist economies, contraceptive options are severely constrained and the information individuals receive is insufficient to making well-founded choices among those options that are available (Bongaarts and Bruce 1995; Bruce and Jain 1995). The latter is also true in the United States, where provider-client exchanges concerning reproductive choice are sometimes glaringly inadequate and contraceptive users may get much of their information from the media, often incorrectly (Institute of Medicine 1995; Moore et al. 1995; Tanfer 1995).

To come to conclusions about what is needed in the marketplace for contraceptive technology, we now depend on method utilization surveys which theoretically express how consumers vote by using, continuing, or discontinuing a given method. However, the meaning of those votes may be obscured both by

whether they reflected real choice among real options and by who paid for the purchase. Thus, even though we are getting a better grasp on the specific attributes desired in contraceptive technologies by different populations in different circumstances, there is a true need for sophisticated market research in a range of settings (Snow 1994).

Perhaps the best evidence that consumers have long wanted something from the contraceptives market beyond its traditional offerings is the alacrity with which they have seized upon most new methods as they have come along. This has occurred despite the difficulty of "imagining" the new technology and seemingly without reference to anything but whether or not it might "work" (Forrest 1994a). Women are eagerly in search of something that is possibly better, only to be disappointed when they discover that no contraceptive is perfect for everybody; that there are still side effects for some users; that unexpected side effects or complications or inappropriate prescribing and patient management have contributed to litigable cases that muddy the picture of the method's utility; or that manufacturers have not adequately represented what remains unknown about their product.

The WHO/HRP review observes that users differ so markedly from one another in their criteria for selection of a contraceptive method that even people choosing a more or less similar product may be dissimilar in the relative importance they attach to the specific attributes of the product chosen. For instance, the IUD is chosen by women in India, Turkey, and the Republic of Korea primarily for its perceived effectiveness, but for its ease of use by postpartum women in the Philippines. Indian women chose the pill mainly for its ease of use, Korean women for its effectiveness. Indian women also chose the injectable DMPA for its ease of use, while Korean, Philippine, and Turkish women chose it for its convenient duration of action. For some, convenience and desire for spontaneity may determine method choice; others may care deeply about reversibility, discretion, duration of protection, no need for resupply visits, and so forth.

The review concludes that it is difficult—and probably inappropriate—to make large statements about product attributes that supposedly drive all consumer preferences; that there is really no consensus about some set of attributes that are invariable and intrinsic; and that, with the exception of safety and efficacy, all other contraceptive product attributes will vary in their meaning and priority for users according to situation (Snow 1994). In fact, some individuals in some circumstances may be willing to cede some efficacy for other, more valued or situationally appropriate attributes. This suggests that the point made in recent papers (e.g., Correa 1991; Germain 1993) that there has been, overall, undue R&D emphasis on effectiveness at the expense of safety or acceptability may also be situational. The current intent of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to require efficacy trials of existing over-the-counter barrier methods is an example of where efficacy may, in fact, be an inappropriate emphasis. At the same time, any newly developed barrier method designed to protect against either concep-

tion or infection or both would be less attractive were its efficacy not assured at some reasonably safe level. The fact remains that the methods that have so far dominated the market for contraceptives have been those that do offer high efficacy (Ortho 1991, 1993, 1995; Snow 1994; WHO/HRP 1995). It is also true that it is the issue of safety, or the lack thereof, that is at the core of product liability.

All this raises further questions in connection with the ongoing debate about the relative merits of user control compared to provider control; reversibility compared to effectiveness; coitus-independence compared to coitus-dependence; and the need for concealment of contraceptive use compared to the desirability of partner involvement (Forrest 1994a). Some women are quite willing to trade off "having the doctor do it" for what they consider certainty and peace of mind. Some women not in a formalized relationship and whose sexual activity is sporadic are not necessarily opposed to coitus-dependence. Some women have partners with whom they can share contraceptive decision making; others do not. In sum, there appears to be a persistent divergence of opinion about the qualities that are wanted in contraceptives, who wants them, and what they mean to different groups and individuals 13 and it is this divergence that argues for the largest possible range of contraceptive options.

The "Woman-centered Agenda"

Over the past few years, importantly in connection with the International Conference on Population and Development held in Cairo in 1994, some ideas about what is missing in the contraceptives market have become clearer. There have been precise statements about specific technologies that are wanted which are so eminently desirable that they should be construed by industry as virtual instructions. These have become a core element of the "Contraception 21" Initiative launched by the Rockefeller Foundation and have come to be known as the "woman-centered agenda." As explained in Chapter 1, that agenda awards priority to the following contraceptive technologies:

- vaginal methods that protect against sexually transmitted reproductive tract infections, both in conjunction with contraception and independent from it;

- menses-inducers; and

- more methods for men.

Since current technologies are limited, and since a plausible case can be made that there is market demand for such products, these categories constitute market niches that would seem to merit new industrial investment.

Immunologic Contraception