6

The Translators: Sectoral Roles in Contraceptive Research and Development

The Role of Industry in Contraceptive Research and Development

The Pharmaceutical Industry

Stage I: The First Contraceptive Revolution and the Primacy of Industry (1951-1972)

Since the 1950s, the involvement of the pharmaceutical industry in contraceptive research and development has passed through three stages, and it is now in a fourth stage whose future pace and direction are unpredictable. The character of that involvement has shifted in each phase in response to factors in the external environment that are peculiar to the field of contraceptive research and development and, perhaps, to the entire area of women's health. Although this chapter emphasizes the history and contemporary dynamics of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry, it incorporates information about firms outside the United States that are involved in some aspect of contraceptive research and development and raises issues deriving from the ongoing processes of industrial globalization.

Stage I, "the contraceptive revolution," can be said to have begun in 1951 more or less officially, when Carl Djerassi at Syntex filed a patent for norethindrone; it ended in the early 1970s. During this period, most contraceptive research and development was sponsored and carried out by large pharmaceutical companies, especially U.S. firms. The field was "pushed" by advances in steroid chemistry and the emergence of an array of complex plastics, neither of which

had had human contraceptive uses as their original objectives. The developers of these first-phase contraceptives were well aware of cultural sensitivities about contraception and the consequent possibilities of corporate risk, but the perceived technological potential and market demand were overriding. A number of firms became engaged in the development and production of the new oral contraceptives (OCs). In the United States, those were Syntex, Searle, Upjohn, Wyeth, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, and the Syntex-Ortho partnership. Other U.S. firms were engaged in the development and production of the first modern intrauterine devices (IUDs): Ortho, Schmidt, American Caduceus Industries, Searle, and A.H. Robins. In Europe, the first firms to be involved in contraceptive research and development were Schering AG, Ciba, and Organon; British Drug House entered with two OC compounds in the early 1960s, and firms in Canada, Switzerland, and France with improved intrauterine devices in the early 1970s. Upjohn and Schering AG also presented the injectable contraceptives, Depo-Provera and Noristerat, for regulatory approval in this time period.

All this unfolded in a climate of general enthusiasm for the postwar "pharmaceutical revolution," and receptivity to effective, reversible, coitus-independent fertility regulation was rapid and enthusiastic. Regulatory requirements were fairly lenient, particularly for the IUD, and clinical studies were less sophisticated than they are today; thus, R&D time was shorter and effective patent life was longer. The taking of a daily pill over a goodly proportion of the reproductive life promised a large market, and the smaller size of the market for the longacting IUD seemed not to be a problem (Gelijns and Pannenborg 1993). Only one firm abandoned the field during this time: Parke-Davis, whose management was worried about negative consumer reaction and conflict with company values.

Stage II: The Rise of the Public and Nonprofit Private Sectors and a Worldwide Orientation (1973-1987)

The second stage of contraceptive research and development began early in the 1970s, its onset marked by negative reports in the medical and lay press on OC side effects. Senate hearings in 1970 received some sensational press coverage and OC use declined noticeably. At roughly the same time, there were reports of side effects of the IUD, primarily the Dalkon Shield, and Robins took the device off the market in 1974.

The period also saw more stringent regulatory requirements, resulting in the extension of R&D time to between 10 and 17 years and, as a consequence, much greater R&D costs and reduction in effective patent life. The eruption of litigation against Robins spilled over onto other IUDs, as well as to oral contraceptives, and public perceptions of the pill and IUD became quite negative. Although oral contraceptives accounted for just under 4 percent of the prescription drug market as the 1980s began, there were more liability suits associated with that method each year of the new decade than for any other drug product (Djerassi

1989). As for the IUD, even though the copper-releasing and medicated devices were major improvements in safety, liability insurance had become essentially unavailable in the United States; even firms with FDA-approved IUDs left the market—and contraceptive research and development—altogether. Research indicating that IUD risks had been overestimated, together with improvements, motivated numbers of European and some developing-country women to return to the method. However, in the United States, only Alza's Progestasert was able to stay on the market and the IUD became virtually a nonoption for American women, never to regain its market share (Gelijns and Pannenborg 1993; NRC/ IOM 1990). Contraceptive research and development became what it continues to be today: highly politicized, with consumer advocates and some women's groups arguing that developers and policy makers have been generically heedless of the needs and safety of women, and opponents of fertility control arguing against any contraceptive research and development whatsoever.

There was little mistaking the growing reluctance of U.S. industry to invest in contraceptive innovation; the barriers were everywhere. As something of a substitution effect, growing interest in family planning in developing countries drew the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) into the field, accompanied by funding that motivated research activity in universities and nonprofit organizations, especially those with strong international networks. The Center for Population Research at the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), motivated by U.S. domestic concerns, also became a major source of funding for contraceptive research during this stage. In 1972, the World Health Organization's Special Programme of Research, Development, and Research Training in Human Reproduction was established. Among the nonprofit entities that were either created or that became more active during this stage were the Population Council's Biomedical Research Center, Family Health International (FHI), and the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH). There were also over two dozen university-based research programs, some of which also took on roles as intermediary funders of research at other universities, for example the Institute for International Studies in Natural Family Planning (IISNFP) at Georgetown University, the Program for Applied Research in Fertility Regulation (PARFR) at Northwestern University and its successor, the Contraceptive Research and Development (CONRAD) program at Eastern Virginia Medical School.

Wyeth, Schering AG, and Organon, recognizing the long-term profit potential of developing-country markets, set up manufacturing facilities in over 20 developing countries, including Bangladesh, Egypt, India, and Indonesia (PATH 1994). Second-generation lower-dose and multiphasic oral contraceptives, minipills, and more selective progestins reduced side effects and revived the reputation of oral contraceptives; when the secondary health benefits of the method also began to be appreciated, the structure of demand shifted back in their favor. And, owing to the sophistication, greater safety, and lower relative cost of endoscopic

techniques, sterilization became by 1982 the most commonly used method in the United States. In the 1988 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), male and female sterilization together exceeded OC use and, in the 1990 telephone resurvey, sterilization by itself was the most commonly used method (Peterson 1990), even though, as a one-time permanent method with a limited pricing range and much subsidy, it did not offer industry a growing and profitable market niche. However, the profits that ensued from the other therapeutic and diagnostic uses of endoscopy were considerable so that the technology itself, overall, proved quite lucrative (Gelijns and Pannenborg 1993).

Yet the net result of the dynamics of Stage II was that, by the end of the 1980s, women in the United States had one effective reversible method, the pill, and one effective permanent method, sterilization.

Stage III: The Exodus of U.S. Industry and the Entry of Smaller Firms (1987-Present)

Beginning in the late 1970s, all but two of the U.S. pharmaceutical companies that had engaged in contraceptive research and development over the previous two decades had, to all intents and purposes, ceased any significant involvement in that field: Syntex, Searle, Upjohn, Mead Johnson, Parke-Davis, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Eli Lilly, and Wyeth all withdrew, although some remained involved in production. Of the nine large U.S. pharmaceutical firms that had entered contraceptive research and development in Stage I, all but two-Ortho, a subsidiary of Johnson and Johnson, and Wyeth-Ayerst-had exited by the end of Stage III, although Syntex, Searle, Upjohn, and Parke-Davis continued to produce and distribute the products their firms had developed. By the end of the 1980s, innovation in contraceptive research and development in the pharmaceutical industry resided largely in Europe, in the hands of Organon, Schering AG, and Roussel-Uclaf, a Hoechst subsidiary (Gelijns and Pannenborg 1993).

Another significant Stage III phenomenon was the entry into contraceptive research, development, production, and distribution by smaller companies. In Europe, this category has included firms like Gedeon Richter (Hungary), Alphatron (The Netherlands), Bioself (Switzerland), Cilag AG (Germany), Leiras (Finland), and Theramex (France) (see Table 6-9). In the United States a new pattern evolved, one of collaborative effort among public and private organizations: funding agencies, basic research facilities, university-based scientists, clinical trials organizations, nonprofit organizations, and smaller pharmaceutical companies, some of which were outside the U.S. (see Bronnenkant 1994). These organizational arrangements were unlike the standard model in the two preceding decades, that is, the single, large, integrated pharmaceutical company with, at most, one industry or nonprofit partner. In those years, basic research had been as likely to come out of industry as it was to emerge from the academic research community. In contrast, the multisectoral arrangements of the 1980s were flex-

ible, opportunistic, varied, and complex, and the industry component was just one of several and as likely to be a smaller firm as a larger one. Almost all of these collaborations were focused on modifications of and new delivery systems for existing or improved compounds, namely:

- VLI (purchased by Whitehall Laboratories), National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD): vaginal sponge (Today) 1

- Medisorb (formerly Stolle Research and Development Corporation), Ortho, World Health Organization (WHO), Contraceptive Research and Development Program (CONRAD), Family Health International (FHI): injectable microspheres

- Finishing Enterprises, Population Council, World Health Organization, Rockefeller Foundation, Ford Foundation: Copper T intrauterine device

- Wyeth-Ayerst, Leiras, Population Council, FHI, Program in Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH), individual clinical researchers worldwide: Norplant implants

- Ortho, Salk Institute, Medisorb (Stolle): LHRH analogues

- Alphatron, Vastech Medical Products, Population Council: nonsurgical vasectomy devices

- Upjohn, Dow Corning, Population Council, Battelle Institute, London International, Roussel UK: hormone-releasing vaginal rings

- London International, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Family Health International: polyurethane male condom (e.g., Avanti)

- Tactyl Technologies/SmartPractice, Contraceptive Research and Development (CONRAD) program: nonlatex (Tactylon) male condom

- Wisconsin Pharmacal, CONRAD, FHI, Reddy Health Care: female condom (Reality)

- YAMA, CONRAD, FHI: Lea's Shield.

Stage IV: The 1990s and the Biopharmaceutical Industry

The global pharmaceutical industry of the 1990s is composed of a great array of corporations devoted to the discovery, development, and commercialization of new pharmaceuticals. Over the years since the introduction of oral contraceptives, the industry has evolved and changed in response to a number of factors that are highly relevant to further advances in contraceptive research and development. Those factors include increases in the regulation of pharmaceuticals; a changing economic environment that has driven industry restructuring and stressed a global view of pharmaceutical markets; and—importantly—dramatic growth in the scientific tools and understanding of biology available to assist in the development of new pharmaceuticals. This understanding and these tools have spawned a whole new subset of the industry that is called the biotechnology

sector and, in fact, suggest that the industry can be thought of as the "biopharmaceutical industry." The emergence of the biotechnology sector, together with what some analysts have referred to as a "structural revolution," are producing an ever-wider range of companies that differ greatly in size and organization; in the variety of their product development focus; and in the extent to which they either address the entire drug development process from basic research through to the marketing and sale of approved products or, instead, focus on one or more individual steps within that process.

The Demography of the Biopharmaceutical Industry

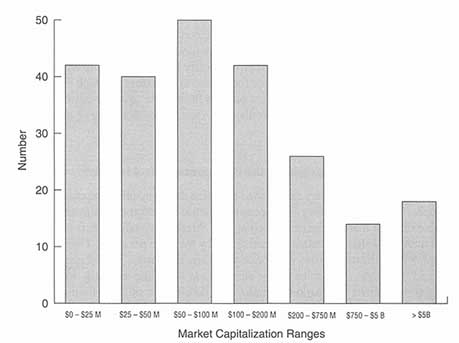

Numerous parameters can be used to define the companies that comprise the biopharmaceutical industry. One common metric is market capitalization, or the value that the market places on a company. Market capitalization is defined as the number of shares outstanding multiplied by the price per share. Clearly, since market capitalization varies with price per share, this metric is most easily determined for public companies whose shares trade on public securities exchanges. Figure 6-1 shows the market capitalization distribution of 232 pharmaceutical/ biotechnology companies that are traded on U.S. exchanges. These companies range in market value from over $5 billion (e.g., Merck, Glaxo-Wellcome) to under $25 million (many small, public biotechnology companies). Absent from this chart is information on over 1,200 private small biopharmaceutical companies in the United States and Europe which tend to have market capitalizations of less than $100 million and most of which do not yet have any product revenues.

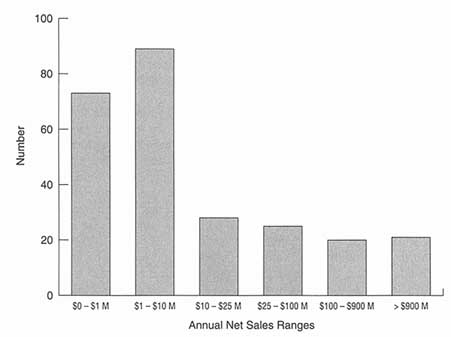

Figure 6-2 shows the annual net sales distributions of 244 pharmaceutical/ biotechnology companies that trade on U.S. public exchanges. The bulk of revenues produced by these companies is generated by a minority of large corporations. To emphasize this point, the accounting firm of Ernst and Young has calculated the "Merck/Biotech Index," an assessment of the entire developing biotechnology industry as compared with Merck's ethical pharmaceutical business. According to the latest Ernst and Young survey in 1995, Merck had reported $15 billion in revenues, compared to $12.7 billion in revenues for the entire biotechnology industry for the 12-month period ending June 1995. During the same period, while Merck invested $1.2 billion in research and development and had a workforce of 47,500, the biotech industry invested $7.7 billion in research and development and had a work force of 108,000. In other words, R&D investment, while intense throughout the biopharmaceutical industry, is most heavily concentrated in the emerging company subsector. Industry estimates are that, despite the large investment of public funds in disease-specific areas, 92 percent of all drugs approved between 1981 and 1990 trace their origin to private sector R&D programs. The growing importance of the R&D effort within young entrepreneurial companies is emphasized by statistics that show that even in R&D-intensive large companies such as Merck, 50 percent of all

Figure 6-1

Market capitalization distributions of public pharmaceutical/biotechnology companies. B = billion; M = million. Source: Disclosure Annual Industrial Database, 1995.

products presently in clinical trials were licensed from small companies and, to a lesser extent, universities.

Contemporary Industry Dynamics

There is little disagreement that the years since the late 1980s have brought profound transformations in the marketplace for human health products. The prospect of health reform accelerated a reorganization of the health care marketplace that was, in some respects, already under way. The precipitating factor was the relentless run-up in health care expenditures in the United States and the sense of urgency about the need to contain costs and shift from fee-for-service arrangements to managed care systems. The competitiveness and profitability of such systems depend on their cost-effectiveness. As a result, fixed-fee and capitation schedules, protocols, and guidelines have been implemented or recommended. In the same vein, there is growing interest in formularies and a consequent burgeoning of pharmacy benefit management organizations (PBMs) as

Figure 6-2

Annual net sales distributions of public pharmaceutical/biotechnology companies. M = million. Source: Disclosure Annual Industrial Database, 1995.

ways to control the costs of pharmaceuticals. Health care purchasers in the 1980s, who were primarily physicians, tended to be generally cost-insensitive. Pharmaceutical profitability in the 1980s had exceeded all other industry sectors and drug companies had been able to grow almost entirely owing to price increases. It is now clear from different challenges to industry pricing that this strategy is no longer viable (Easton 1993; Pollard 1993).

The pharmaceutical industry has been adapting to these realities by essentially reconfiguring itself. Some firms are moving toward domination of a small number of specialty areas, some toward vertical expansion throughout the health value chain. Some are increasing their size in the belief that greater critical mass will drive success, others are aiming at being total disease-management companies in which drugs are just a part of total health care solutions.

The specter of shrinking profit margins has also motivated companies to view market share—that is, the percentage of sales within a particular market segment—as the most important determinant of near- and long-term success. The sense is that market share leaders will be the most cost-efficient players, whose cost-efficiency will yield them savings for reinvestment in research or for the sourcing of higher-value products (Easton 1993). Companies are attempting

to retain market share for the drugs now coming off patent by converting them into over-the-counter (OTC) drugs; by building relationships with pharmacy benefit management organizations; by limiting price increases; or by responding to competition from generic drugs, either by building their own generic businesses, licensing out generic conversions of their drugs, or acquiring generic companies outright.

Some industry analysts argue that there will be an inevitable decline in the number of new drugs, for two reasons. One is that the science is more complicated; the other is that providers will increasingly depend on drug formularies to control costs. Furthermore, there is evidence that patients may have a much more powerful voice in determining managed care buying practices. Selection, addition, and substitution of formulary products will be based on product price and the amount of therapeutic or ''user value" added, so that product improvements that are merely incremental are likely to be far less important than in the past. Yet, while "me too" and "incremental" products will be less attractive in the future, the opportunity for cost-effective "breakthrough" products for unmet medical needs remains. As a consequence, pharmaceutical companies will not just need to be more cost-efficient inventors, developers, and marketers to make more products pay off for shareholders; they will also have to be disciplined in focusing their research investment on a smaller, more select group of therapeutic categories. Speed to market, always important, will become more so. Established, experienced pharmaceutical companies will have an advantage because they have the best scientific understanding of what is needed in the field and the greatest resources to buy the innovative research required to develop the truly novel drugs that can break into formularies. Thus, despite pressure to cut prices and reduce profit margins, innovation and heavy R&D investment will continue to fuel the industry, with high rewards for novelty and being early to market with products that lower the cost of health care (Burrill and Lee 1993; Pollard 1993). For the large pharmaceutical companies ("big pharma") and for biotechnology firms, "pharmacoeconomics," or the linking of quality-of-life and outcome measures with efficacy data in the design and conduct of clinical trials, will be essential; it will be crucial in the development of products for "difficult audiences."

The need of the large pharmaceutical industry to purchase technology in some form is highly significant for the biotech industry and there is a sense that the redefinition of the pharmaceutical industry offers biotechnology a much wider set of opportunities to prove its value. As noted above, because biotechnology firms essentially invest all of their assets in research and development, they are far from losing their identity as the incubators of much of the progress in human health care (Lee and Burrill 1995). Table 6-1 depicts different dimensions of the way the pharmaceutical industry is being reshaped, its likely future directions, and the way innovative products might be expected to fit into that picture.

The Biotechnology Industry

Industry Structure

Most analysts trace the emergence of the "biotech industry" to the late 1970s/ early 1980s, with the foundation of a series of companies (Cetus, Genentech, Amgen, Biogen) that were started to exploit the commercial potential of recombinant DNA (rDNA) and monoclonal antibody (MAb) techniques. The former involves transferring genetic information from one organism to another, splicing and "gluing" it onto a vector molecule, and replicating or cloning it for a variety of purposes. MAb technology takes advantage of antigens on the surfaces of invading agents to trigger immune-system recognition and response in the form of antibodies, proteins that attach themselves only to the foreign antigen and nothing else, signaling subsequent processes that then destroy the invader. It is the specificity of MAbs, as well as the fact that they can be enlisted as transport mechanisms, that makes them so valuable in the development of diagnostics, therapies, and vaccines.

The techniques, once seen as arcane, have become commonplace. Yet the tradition of novel technology deployed to define and address problems in human health care, agriculture, and animal health remains the hallmark of biotech companies. Thus, new technology stories are often the hallmark of new companies, so that gene therapy, xenotransplantation, genomics, and the like have been fostered first in biotech companies and then been transferred to "big pharma" via partnership, acquisition, or adoption.

From its birth, the biotechnology industry has confronted a set of factors or "hurdles" whose confluence is seen as unique: massive breakthroughs in science and technology (but quite upstream in the R&D process); enormous capital needs with a long horizon to payback; financial markets and investor expectations that turn alternatively hot and cold; a regulatory hand that is seen as heavy; uncertainty about intellectual property rights; and a cost crisis in its primary market, which is health care (Burrill and Lee 1993). Financial analysts are unable to describe public biotech companies to their investment clients using standard financial parameters because the majority of these companies are essentially R&D operations without products, revenues, and earnings. The financial community has therefore adopted a categorization of companies that describes where they are in the product development and company development process. A jargon has emerged that divides companies into first-tier, second-tier, and third-tier. The first-tier companies have products and product revenues and can be judged using standard financial criteria (e.g., Chiron, Amgen, Genzyme). Second-tier companies have products that are new or close to the market and have established the business infrastructure needed to be a self-supporting entity (e.g., Cephalon, Matrix Pharmaceuticals). The third tier has the biggest population and generally consists of companies that went public in the last three years, with

TABLE 6-1 Trends, Worldwide Pharmaceutical Industry, 1970s and Beyond

|

Early 1970s-Mid-1980s |

Mid- 1980s-Mid- 1990s |

Mid- 1990s and Beyond |

|

Consolidation |

Further Consolidation |

|

|

Many small companies |

Fewer, larger corporations |

Few, large corporations Small boutiques |

|

Domestic focus Technology driven |

Global focus Technology dependent Sales/service/distribution driven Competitive pricing Lower profitability Increased government regulation |

Global reach Technology dependent Sales/service/distribution driven Competitive pricing Potential to increase profits Increased government regulation Managed care |

|

Managed Care and the Pharmaceutical Industry |

|

|

|

Past |

|

Future |

|

Approvable products (safety/efficacy) |

|

Marketable products (pharmacoeconomic outcomes) |

|

Cost-based pricing |

|

Positioning on value |

|

Mega sales force |

|

Multiple distribution techniques |

|

Customer service |

|

Customer alliances * Disease management * Outcomes studies * Education * Customized phase III and IV clinical trials |

|

Science/sales driven |

|

Customer/market driven |

|

Early 1970s-Mid-1980s |

Mid-1980s-Mid-1990s |

Mid-1990s and Beyond |

|

Evolution of Successful Products |

||

|

Innovative products |

Innovative products |

Innovative products supported by global sales, service, and market infrastructure |

|

|

Competitive products supported by strong infrastructure |

|

|

Competitive niche products |

Competitive niche products |

Competitive niche products |

|

Sources: Burrill GS, KB Lee Jr. Biotech 94: Long-Term Value, Short-Term Hurdles (The Industry Annual Report). San Francisco, CA: Ernst and Young US, 1993. Noonan KD. Trends in the in vitro diagnostics industry in the late 1990s. Clinica, Special Supplement, April 1994(1). |

||

products still in preclinical animal testing or Phase I human clinical trials, with profits not expected till the end of the decade. Responses by several hundred industry CEOs to annual surveys by Ernst and Young continue to indicate that the largest, most mature, "top-tier" companies are mainly concerned about the complex regulatory environment, with some cyclical concerns about availability of capital. Mid-tier and small (lower-tier) companies worry most about inaccessibility and cost of capital. Unpredictability in the patent environment is significant for all biotechs, as it is for the large companies. The synergy between all these factors over the years has made the biotechnology subsector persistently volatile and its financing platform has generally been rocky.

Industry Strategies

As a result, the industry response has had to be one of very great ingenuity and flexibility, qualities that have been expressed in a plethora of strategic adaptations whose main objective was to somehow access costly resources to complete product development. A few firms tried to become fully integrated pharmaceutical companies, others to become vertically integrated firms in a niche area. A large number of firms sought to establish enough value to justify placing an initial public offering as a way of accessing capital; others worked to develop a blockbuster product as a route to acquisition by a larger company; and still others emphasized products that would require partnering with large companies in order to reach the market.

Virtual Integration Gradually, however, these strategies have been supplanted by other approaches that reflect adjustments to the realities of the changing marketplace, funding difficulties, and developmental disappointments. By 1994, the Ernst and Young annual industry analysis noted a paradigm shift to "virtual integration" and a proliferation of very pragmatic, selective, flexible relationships between biotechs and between biotechs and pharmaceutical companies (see Figure 6-3). These have included, but were hardly limited to, product swaps; development or acquisition of generic product lines; licensing in technologies, particularly late-stage technologies; partial acquisition of units or products; various combinations of different resources; and all manner of strategic partnerships (Lee and Burrill 1995).

Outsourcing Companies are also outsourcing, with high cost-effectiveness, to organizations that provide very narrowly defined services. A prime example is the "contract research organization" (CRO), an entity of possible practical interest in thinking about new strategies for revitalizing contraceptive research and development. CROs are basically third parties that provide research services on a contractual basis, focusing primarily on designing, conducting, and analyzing human clinical trials. Many CROs can also provide preclinical animal testing at

|

FUNCTION |

OWN Resources |

POTENTIAL PARTNERS |

|

Postmarketing sales support |

Statisticians, record keeping |

Specialty firms |

|

Distribution |

Warehousing, shipping Distribution |

Drug wholesalers Generic companies Direct to buyers (e.g., HMOs, government, insurance companies) |

|

Sales |

Detailing |

Customers Big pharmaceutical companies |

|

Marketing |

International and domestic coverage |

* By market/indication * By geography Speciality marketers |

|

Manufacturing |

Manufacturing plant |

Contract manufacturers Specialty-focused biotech intermediaries Big pharmaceutical companies' excess capacity |

|

Clinical/regulatory development |

Clinical expertise |

Clinical research organizations Big pharmaceutical companies Other biotech companies Specialty consultants/ contractors |

|

Development research |

R&D spending Academia |

R&D institutions Big pharmaceutical companies Government Other Biotech companies |

Figure 6-3

Virtual integration. Source: Burrill GS, KB Lee Jr. Biotech 94: Long-Term Value, Short-Term Hurdles (The Industry Annual Report). San Francisco, CA: Ernest and Young US. 1993.

the front end of the development cycle and regulatory consulting services at the back end. While CROs have existed for more than two decades, a confluence of factors seems to be driving a resurgence. These factors include pricing pressure from organized buyers; a relative paucity of investment capital; staff cutbacks; lack of expertise in most biotechs in clinical development and in regulatory affairs; perceived increases in regulatory burdens; and buyers' demands for cost-efficiency data which add a whole new layer of complexity to clinical development strategies. (Examples of such companies are Quintiles Transnational, IBAH, and Clintrials.) The role of CROs is becoming more prominent as a feature in company strategies, particularly for those that can respond to the demands of drug companies for global capabilities so that products can be tested and filed

simultaneously for approval worldwide. At one extreme, Abbott Pharmaceuticals contracts 80 percent of all its clinical development to CROs, other companies as little as 10-20 percent; industry trends are thought to be moving toward 50 percent. The volumes in dollar terms are not small: As of 1994, pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies were spending in aggregate roughly $26 billion annually. Of this amount, about two-thirds, or $17 billion, was spent on the kinds of services that CROs provide (Kreger 1994).

Alliances It is not surprising, then, that there has been steady growth in strategic alliances involving the biotech industry from the start of 1993 to mid-1995 (see Table 6-2). If the mid-1995 transaction rate is sustained, over the past three years there will have been close to 500 strategic alliances involving biotech companies, over 300 of those with large pharmaceutical companies and 150 with other biotechs. The number of mergers and biotech acquisitions is considerably less, a total of 123 projected for the same period (see Table 6-3). Table 6-3 shows the numbers of strategic alliances along with the numbers of financings, mergers and acquisitions, and downsizings as ways in which industry accesses capital, makes clear the relative importance of such alliances in overall industry strategy.

What may be surprising is that the biotech industry is not shrinking overall (see Table 6-4), despite the prevalent view among industry analysts who feel that there are too many biotechs and that some rationalization and compression will be necessary. The total number of companies, including those that have gone public, grew steadily over the same three-year period (1993-1995) and the industry's work force grew as well, even though an estimated 68 firms were seen as downsizing by the end of 1995 (see Table 6-4).

Globalization Another effect of the changes in the larger environment for "big pharma" and the biotech industry is that the industry has become increasingly

TABLE 6-2 Strategic Alliances in the Biopharmaceutical Industry, 1993 to Mid- 1995

|

|

Number of Transactions |

|

|

|

|

1993 |

1994 |

Year to Date 6/30/95 |

|

Large pharmaceutical company alliances with biotech company |

69 |

117 |

73 |

|

Biotech-and-biotech alliances |

43 |

52 |

26 |

|

Total |

112 |

169 |

99 |

|

Source: Vector Fund Management. BioWorld Financial Watch. Deerfield, IL 1995. |

|||

TABLE 6-3 How Biotechs Access Capital

|

|

Number of Transactions |

|

|

|

|

1993 |

1994 |

Year to Date, 6/30/95 |

|

Financings |

190 |

174 |

105 |

|

Mergers and acquisitions |

21 |

48 |

27 |

|

Downsizing |

6 |

26 |

18 |

|

Strategic alliances |

112 |

169 |

99 |

|

Source: Data provided by Vector Fund Management, Deerfield, IL 1995. |

|||

global. Products are being developed with the intent that they will be made available to patients in many different countries. Consequently, many companies have operations in those countries; those that do not must develop extensive contractual relationships to allow their products to reach global markets. The implications of a global biopharmaceutical marketplace are profound. From the conception of a clinical program through development and launch, decisions must be made with an eye to entering markets governed by divergent rules. The globalization of business, coupled with the need to be more cost-efficient, is behind the movement to "harmonize" criteria for drug development and approval and has led to the creation of new companies that can expeditiously facilitate new drug development across borders; international CROs are an excellent example of this adaptation.

Furthermore, the biotech industry is growing in Europe, which as of 1994 had 386 biotech companies (Lee and Burrill 1995). In consequence, many European pharmaceutical and biotech companies are creating alliances with U.S. firms, providing capital as well as manufacturing and marketing support; and regulatory filings for foreign investment have increased dramatically. In addition, Europe's often less stringent regulatory requirements offer the opportunity for U.S. companies to initiate clinical trials more quickly and possibly gain market access sooner; other operational and tax advantages also add to the general offshore allure. Finally, the biotech industry has globalized to include countries in Latin America, Eastern Europe, China, India, and the Pacific Rim, which recognize the promise of biotechnology, offer new markets, and serve as sources of innovation. Corporate partnerships and sale or licensing of product rights are the strategies favored for penetrating the European and Japanese markets, with strategic partnerships also receiving significant emphasis in the United States. Going it alone in either terrain is difficult: International expansion inevitably requires additional infu-

TABLE 6-4 Biotechnology Industry Highlights ($ billions), 1992-1995

|

|

Public Companies (Merck Index)a |

Biotech Industry Total |

||||

|

|

This Year |

Last Year |

%Change |

This Year |

Last Year |

%Change |

1995 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sales/revenues |

$15 |

$10.5 |

47 |

$12.7 |

11.3 |

12 |

|

R&D expense |

$1.2 |

$1.2 |

0 |

$7.7 |

$7.1 |

6.4 |

|

Net income (loss) |

$3.0 |

$2.2 |

26 |

$(4.6) |

($4.2) |

10 |

|

Market capitalization |

$73.0 |

$3.7 |

97 |

$52.0 |

$41.0 |

0.7 |

|

Employees |

47,500 |

47,100 |

1 |

108,000 |

103,000 |

2.3 |

|

1994 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sales |

$5.2 |

$4.3 |

20 |

$7.7 |

$7.0 |

10 |

|

Revenues |

$7.1 |

$6.0 |

17 |

$11.2 |

$10.0 |

12 |

|

R&D expense |

$3.8 |

$3.0 |

27 |

$7.0 |

$5.7 |

23 |

|

Net loss |

$2.1 |

$1.5 |

40 |

$4.1 |

$3.6 |

14 |

|

Market capitalization |

$36.0 |

$39.0 |

(8) |

$41.0 |

$45.0 |

(9) |

|

No. of companies |

265 |

235 |

13 |

1,311 |

1,272 |

3 |

|

Employees |

53,000 |

48,000 |

10 |

103,000 |

97,000 |

6 |

|

1993 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sales |

$4.4 |

$3.3 |

35 |

$7.0 |

$6.0 |

17 |

|

Revenues |

$6.1 |

$4.4 |

38 |

$10.0 |

$8.3 |

20 |

|

R&D expense |

$2.9 |

$2.4 |

24 |

$5.7 |

$5.0 |

14 |

|

Net loss |

$1.4 |

$1.4 |

0 |

$3.6 |

$3.4 |

6 |

|

Stockholders' equity |

$10.5 |

$8.1 |

30 |

$15.9 |

$48.0 |

(6) |

|

No. of companies |

235 |

225 |

4 |

1,272 |

1,231 |

3 |

|

Employees |

48,000 |

37,000 |

30 |

97,000 |

79,000 |

23 |

|

1992 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sales |

$3.4 |

$2.6 |

31 |

$5.9 |

$4.4 |

3.5 |

|

Revenues |

$4.5 |

$4.5 |

29 |

$8.1 |

$6.3 |

28 |

|

R&D expense |

$2.3 |

$1.5 |

54 |

$4.9 |

$3.4 |

42 |

|

Net loss |

$1.4 |

$0.9 |

60 |

$3.4 |

$2.6 |

32 |

|

Stockholders'equity |

$8.2 |

$4.5 |

83 |

$13.6 |

$10.7 |

27 |

|

No. of companies |

225 |

194 |

16 |

1,231 |

1,107 |

115 |

|

Employees |

37,000 |

33,000 |

12 |

79,000 |

70,000 |

13 |

|

a The MERCK Biotech Index is a measure devised by Ernst and Young, which assesses the entire developing biotech industry as compared with Merck's ethical pharmaceutical business. Sources: Ernst and Young Biotech Industry Annual Reports: Biotech 93, 94, 95, 96. |

||||||

sions of money, talent, and local know-how concerning regulatory approvals, product pricing and reimbursement, and marketing.

The theory has been advanced that an increasingly global market might be helpful in alleviating some of the constraints to contraceptive research and development that prevail in the United States, in terms of offering options for collaborative relationships (Rockefeller Foundation 1995a). Prominent among the arguments are that the regulatory environment might be less stringent elsewhere, that the pressures of liability would be less severe, that the political and ideologic environment might be less complex, and that clinical trials would be less costly. These are reasonable arguments to advance but each of them requires a complex and thoughtful examination, beyond what this study committee found feasible within its own constraints of time and resources. Another major—and persistent—constraint is the very real limitation of access to information, most importantly about prospective industrial relationships, information that is almost always well guarded. A brief retrospective glance at some partnership experiences, such as the efforts of some small U.S. firms to partner with European firms, Roussel-Uclaf s experience with RU 486, and the some of the experience with offshore production, have been too complex and the determining variables too diverse to permit easy, categorical conclusions. As just one example, the mutual perceptions of the United States and the European countries of the stringency of each other's regulatory processes appear to be quite discordant and efforts at harmonization move slowly.

The Risk-Benefit Assessment: Decisions by Private Firms to Invest

The General Process

The theme of financing has pervaded the present discussion because it lies at the heart of the complicated web of interdependence that is being woven among biotechnology and large pharmaceutical companies, in the United States and overseas. And, at the heart of the financing issue is the fact that the process of developing new pharmaceutical products is complex, long, and costly (see Figure 6-4). Estimates of the time and costs involved in developing new therapeutic ethical pharmaceutical products and taking them to market vary widely. A major source of variance is the product category itself; new chemical entities (NCEs) typically take more time and cost more money (OTA 1993). A 1989 industry survey estimated that 83 percent of total U.S. R&D dollars in that year were spent in the earliest stage of the process, that is, in advancing scientific knowledge and developing new products, as opposed to improving and/or modifying existing products though distinctions between these two categories of endeavor can be fuzzy (OTA 1993). This period of conceptual work and initial synthesis is also inherently risky; it may be that, out of every 10,000 new chemicals synthesized in the laboratory, FDA approval may be sought for only 1 (NRC/IOM 1990). And,

of 20 entities submitted to FDA for approval, only two may be approved and just one may actually be introduced as a new product (Harper 1983; NRC/IOM 1990; OTA 1993).

In 1993, the Office of Technology Assessment (OTA) reanalyzed earlier seminal studies of the costs of pharmaceutical R&D and calculated an average cost of developing a new drug at ''no more than" $237 million (OTA 1993), with development time from identification of an NCE to market taking from 10 to 12 years. According to the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers Association (PhRMA), the range can be from $100 million to $500 million and take a minimum of five to ten years from the time a decision is made to take a product into clinical development to the time it appears on the market. While this wide range in cost estimates may be related to product-specific needs, such as duration and number of patients in a series of clinical trials, they may also have to do with amortization of a large company's overhead vis-à-vis that of a "lean and mean" entrepreneurial biotechnology company. Still, it is simplistic to assume that product development will always be less expensive in biotech companies.

The Specific Case of Contraceptive Research and Development

One of the most important influences on the development of new contraceptives is the outcome of decisions by U.S. and European producers of pharmaceuticals and medical devices. Although governments and nonprofit organizations have made significant contributions to the funding of basic research and to the development of many contraceptive technologies, most of the currently available products were commercialized by U.S. and Western European firms.

A promising "reservoir" of basic biomedical research may be necessary, but it is by no means sufficient, to result in the introduction of new contraceptive technologies. Since basic scientific advances may have a number of possible pharmaceutical or medical device applications, choices about developing one or another of those will depend on assessment of a range of technologic, regulatory, and market factors. In addition, bringing a new contraceptive product to market takes years because of the long development cycle, numerous clinical trials, and complex regulatory approvals that are needed. Thus, today's dearth of new contraceptive products reflects decisions by pharmaceutical firms not to pursue research or development of new contraceptive products that were made 10-20 years ago.

It is tempting to seek single-factor explanations for what has or has not happened in the field of contraceptive research and development. The committee has struggled to do that and been confounded by the idiosyncracies of each "decision experience," since those respond to producer/product/provider/consumer characteristics, varying among themselves and according to time and circumstance. At the most fundamental level, these decisions are not controlled by any single factor but are the outcome of a comparison of the costs and returns

(adjusted for risk, which is unusually significant in this product area) from investment in contraceptives, relative to alternative development programs and projects. In other words, a decline in development activities in contraceptives could have nothing to do with the economic or political conditions surrounding contraceptives but instead reflect significantly improved opportunities in some other product area. In fact, the situation with respect to contraceptives appears to reflect the operation of both forces—opportunities in other areas have improved, even as the risk-adjusted returns associated with new contraceptive products may have declined.

The decisions of firms, especially those previously active in contraceptive development, not to pursue development of new products, or to exit this product area altogether, also can negatively affect the stock of expertise needed to develop new products. Firms in the pharmaceuticals industry also typically specialize to some extent in specific types of products or therapies, which reflects the fact that they have accumulated considerable scientific, technical, and market related knowledge that is specific to these areas and may not be relevant elsewhere. This type of knowledge often is not easily transferred between firms and cannot be purchased or otherwise acquired by a new firm without a long period of investment and learning. Because a number of firms formerly active in contraceptive technologies have exited this product area, much of this expertise has been lost and would be entrants into the contraceptives field (e.g., biotechnology firms) cannot easily acquire it from incumbent firms or from other sources. Reversing the effects of firm exit on this stock of "know-how" thus may take considerable time.

The factors that must be considered when industry assesses a new biopharmaceutical program are:

- market

- management/human resources

- technology assessment

- competition

- regulatory requirements

- intellectual property position

- economics

- —cost to develop (time, money, people)

- —competitive position at launch

- —projected profitability

- —opportunity cost vis-à-vis other programs

- strategic reasons

- —synergy with other efforts

- other factors

- —e.g., political risk.

Simplifying the problem considerably, and abstracting from the issue of

know-how, an individual firm's decision to pursue development of a new contraceptive technology (which may yield a family of products) is governed primarily by the expected returns to the large investment needed to commercialize this technology, i.e., the profits, relative to the costs of development (one way in which know-how enters this decision is in the confidence and reliability of a firm's judgments about costs and returns). There seems to be little evidence suggesting that the costs of developing a new contraceptive product per se are significantly higher than those involved in developing other pharmaceutical or medical products intended to be used for chronic administration: All of these products require lengthy development programs and large investments in clinical trials and regulatory approvals.

The differences between contraceptives and other pharmaceutical products appear to be more prominent, however, in the area of expected returns and the adjustments imposed by decision makers to adjust these returns for the risks associated with contraceptive products. Market success, especially for contraceptives, requires that a new product offer significant advantages in terms of factors like safety and convenience, as well as being reasonably competitive on price with existing products. Because existing contraceptive products (e.g., IUDs or oral contraceptives) are relatively inexpensive, they impose a "ceiling" on the feasible price in mass markets for new alternatives, and therefore depress projected returns from contraceptives relative to other pharmaceuticals or medical devices, whose delivery is more frequently covered by third-party reimbursement.

A rational decision maker will also adjust expected returns for risk, and this adjustment is likely to prove disadvantageous to contraceptives relative to other products. Riskier products demand a higher expected return in order to justify the investment in their development, and contraceptives appear to exhibit relatively high risks from two sources. The first is liability litigation, which is an unusually serious threat in contraceptives, just as it has been in vaccines (this factor is a serious risk mainly in the United States, but litigation risk appears to be increasing in several Western European markets as well). Like vaccines, contraceptives typically are administered to a huge market of individuals with normal health histories. As a result, the possibilities of side effects or unusual reactions, which may affect a very small fraction of the population, will yield a steady stream of claims. Moreover, many of these claims will be filed by healthy, often relatively young individuals and therefore may result in high damage awards. Thus, litigation risk in contraceptives appears to be unusually high relative to other pharmaceutical products.

The committee had entertained the idea of doing some comparative analysis of the costs of litigation for contraceptives compared to vaccines as a somewhat analogous category of products. However, considerable efforts to obtain hard data proved fruitless, since information about such costs is tightly held. The only information of this sort that appears in the public domain concerns the amounts of

awards from cases that do go to court, a small tip of a large iceberg. Of the 2,063 suits filed against Searle over the past 20 years in connection with its intrauterine device, just 24 went to trial; approximately 800 were settled out of court for undisclosed amounts (Steyer 1995). It has been customary to think of litigation as a U.S. issue; however, 346 of the complaints against Searle were "foreign," primarily in Australia and the United Kingdom.

One must add to the financial risks associated with litigation the financial and other risks associated with the strong political opposition to many forms of contraceptive technology in the United States. These risks mean that the projected "hurdle rate" of return that a firm will require to undertake a contraceptive development project will be higher than the hurdle rate associated with other projects. When one combines this requirement for a higher hurdle rate of return with the low prices of the alternatives currently available, contraceptive development projects are likely to appear less attractive than alternative applications. Obviously, for firms with considerable expertise in this product field, this gap between the hurdle rate for contraceptives and other products will be lower, and this gap will be affected by many other influences as well. Nevertheless, these factors appear to depress the projected returns for commercial contraceptive development projects relative to those in other areas in which scientific advances may offer equally enticing product development possibilities.

If, as many analysts suggest, the biotech sector is the pharmaceutical industry's "R&D department," then one surrogate of the perceived commercial attractiveness of new products in women's health might be the number of biotech firms that report to be working in this area. A 1995 survey by Goldman Sachs of the product programs in 158 public biotech companies found that out of over 450 products undergoing clinical testing, only 5 described as "for women's health" had reached that stage (Goldman Sachs 1995). Still, in 1994 PhRMA reported that, among the large number of new drugs in development, there were "143 biotechnology medicines [and] 301 medicines for women" in pharmaceutical company pipelines. In terms of numbers, medicines for women were second only to the "327 medicines for older Americans" and well ahead of the 103 medicines for AIDS and AIDS-related diseases (PhRMA 1994). There seems to be growing attention to the area of women's health in the pharmaceutical industry: Ortho, Parke-Davis, Searle, and Wyeth-Ayerst all have what are considered more or less formally as ''women's health programs." At the same time, only Ortho and Wyeth-Ayerst include contraceptives as part of that picture.

In conclusion, decisions of private firms to reduce their development efforts in contraceptives reflect the operation of a range of factors. No single factor dominates all others in the large majority of individual cases, and no single factor is inevitably the cause across all cases. Contraceptives are competing for scarce technical talent and funds with alternative product development programs, and the commercial attractiveness of other product development projects may shift for any one of a great variety of reasons. Moreover, because of the size and the

duration of the private-firm investments necessary to bring a new contraceptive technology to market, one might see a decline in commercial development activity in the face of continued public support for the basic science underpinning contraceptive technologies. But when declines in public research support are combined with factors tending to depress the relative return on investment from contraceptive development projects, development activities are likely to be curtailed even more severely.

Current Industry Involvement in Contraceptive Research and Development

As of 1993, there were 57 manufacturers or "vendors" of contraceptive and fertility products in the United States (see Table 6-5).2 Of those, 23 were manufacturers or vendors of contraceptive products. The committee identified over twice that number in the worldwide market (see Table 6-6).

One might expect contraceptives and fertility products to be areas of industrial interest with some affinity. In fact, there is surprisingly little crossover; firms active in both areas are usually subsidiaries or divisions of multinational pharmaceutical companies which have enough power and financial resources to develop products in several markets. Just five firms work in both product lines: Organon, Ortho, Syntex, Whitehall, and Wyeth-Ayerst. Ortho is a Johnson and Johnson subsidiary, Wyeth-Ayerst and Whitehall are part of American Home Products Corporation, and Organon is a subsidiary of Akzo NV. Only one, Ortho, which markets oral contraceptives, diaphragms, and spermicidal preparations is present in more than two product lines (Frost and Sullivan 1993). With its acquisition in summer of 1995 of GynoPharma, which dominated the U.S. market for IUDs and also had a line of spermicides, Ortho further increased its number of product lines and now has more product lines than any company worldwide.

The industrial profiles of the two product areas—contraception and fertility—are quite different. The fertility industry is less dominated by giants than is the contraceptives industry and is scattered among numerous, smaller competitors that tend to focus fairly narrowly, sometimes developing great expertise in a niche market and thereby becoming the dominant firm in that segment. The fertility products subgroup of the market is even more finely grained, counting many smaller participants, for example, those that develop and/or produce immunoassays and nonisotopic hormone tests and are attempting entry (Frost and Sullivan 1993).

The overall industrial picture in contraceptives is far more concentrated; in fact, it is described by at least one prominent industry analyst (Frost and Sullivan 1993) as pretty much an oligopoly, dominated by a few large and strong competitors who account for anywhere from 60 to 90 percent of total manufacturer revenues in this area. Table 6-7 shows revenues by product type and company

TABLE 6-5 Firms Manufacturing and/or Distributing Contraceptives, United States, 1993

|

Firm |

OCa |

Condom |

Diaphragm |

IUD |

Spermicide |

Implantb |

|

Aladan |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Alza |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ansell |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

|

Berlex |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carter-Wallace |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Finishing Enterprises |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

GynoPharmac |

X |

|

X |

X |

|

|

|

Mead Johnson |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Milex |

|

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

National Sanitary |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

Okamoto |

|

X |

|

|

|

|

|

Organon |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ortho |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

Parke-Davis |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rugby Labs |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Schering Plough |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Schiaparelli-Searle |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Schmid |

|

X |

|

|

X |

|

|

Searle |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Syntex |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thompson Medical |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Warner-Chilcott |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Whitehall |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

|

Wyeth-Ayerst |

X |

|

|

|

|

X |

|

a Oral contraceptives. b Norplant. c GynoPharma was sold in the summer of 1995 to Ortho Pharmaceuticals. Source: Frost and Sullivan. U.S. Contraceptives and Fertility Product Markets. New York, 1993. |

||||||

TABLE 6-6 Firms Manufacturing and/or Distributing Contraceptives Worldwide, 1993 and 1994

|

Company |

Product Manufactured or Distributed |

|

Aladan |

Condoms |

|

Alza |

IUDs (Progestasert) |

|

Ansell |

Condoms (including one with nonoxynol-9) |

|

Berlex |

Oral contraceptives (Tri-Levlen, Levlen) |

|

Boehringer Ingelheim |

Oral contraceptives |

|

Bristol-Myers Squibb |

Oral contraceptives |

|

Carter-Wallace |

Condoms (including one spermicidally lubricated) |

|

CCC (Canada)* |

IUDs |

|

Cervical Cap Ltd. |

Cervical cap (Prentif/manufactured by Lamberts/Dalston England) |

|

Chartex (United Kingdom) |

Female condom (Femidom) |

|

Cilag (UK)* |

Oral contraceptives |

|

Dongkuk Trading (Korea)* |

Condoms |

|

Finishing Enterprises* |

IUD |

|

Gedeon Richter (Hungary) |

Emergency postcoital contraceptive (Postinor) |

|

Gruenenthal |

Oral contraceptives |

|

GynoPharmaa |

IUD (CuT380A [Paragard]) (distributor) Oral contraceptive (Norcept) Diaphragms (distributor for Schmid) |

|

Hyosung (Korea)* |

Condoms |

|

Jenapharm (Germany) |

Oral contraceptives |

|

Kinsho Mataichi (Japan)* |

Spermicides |

|

Leiras Oy Pharmaceuticals |

Progestin-releasing IUD (Mirena) |

|

(Finland)* |

Norplant (manufacture) |

|

Lexis |

Oral contraceptives (NEE) |

|

Company |

Product Manufactured or Distributed |

|

London Rubber |

Condoms Diaphragms |

|

Magnafarma |

Oral contraceptives |

|

Mayer |

Condoms |

|

Mead Johnson |

Oral contraceptives (Ovcon) |

|

Medimpex* (Hungary and USA) |

Oral contraceptives/raw materials |

|

Menarini |

Oral contraceptives |

|

Milex Products, Inc. |

Diaphragms (Omniflex, Wide-seal) Jellies and creams (Shur Seal Jel has nonoxynol-9) |

|

National Sanitary |

Condoms |

|

Okamoto, USA |

Condoms |

|

Organon (Akzo) (Netherlands)* |

Oral contraceptives (Marvelon, Desogen, Jenest) IUD (Multiload) (manufacturing subsidiary, Bangladesh) |

|

Ortho Pharmaceutical* (Johnson & Johnson) |

Oral contraceptives (Loestrin; Ortho-Cept, Ortho-Cyclen, Ortho Tri-Cyclen, Ortho-Novum, Modicon) Diaphragms (Allflex, Ortho Diaphragm) Spermicides* (Gynol) IUDs |

|

Parke-Davis (Warner-Lambert) |

Oral contraceptives |

|

Polifarma |

Oral contraceptives |

|

Reddy Health Care |

Condoms |

|

RFSU of Sweden |

Condoms |

|

Roberts |

Oral contraceptives |

|

Rugby Labs |

Oral contraceptives (Genora) |

|

Safetex |

Condoms |

|

Company |

Product Manufactured or Distributed |

|

Schering AG (Germany)* |

Oral contraceptives* Injectables* |

|

Schering Plough (USA) |

Spermicides |

|

Schmid |

Condoms (including spermicidal condoms) Spermicides Diaphragms (distributed by GynoPharma) |

|

Searle (Monsanto) |

Oral contraceptives (Demulen) |

|

Seohung (Korea)* |

Condoms |

|

Syntex |

Oral contraceptives (Tri-Norinyl, Devcon, Norinyl, Brevicon) |

|

Thompson Medical |

Spermicides |

|

Upjohn* (Upjohn Belgium)* |

Injectable (Depo-Provera/DMPA) |

|

Warner-Chilcott |

Oral contraceptives (Nelova) |

|

Whitehall |

Sponge (Today)b Spermicides |

|

Wisconsin Pharmacal |

Female condom (Reality) |

|

Wyeth-Ayerst (American Home Products) |

Oral contraceptives (Lo-Ovral, Nordette, Triphasil) (joint venture, Egypt, production) Norplant (marketing, distribution) |

|

Wyeth-Pharma (Germany)* |

Oral contraceptives |

|

Wyeth (France)* |

Oral contraceptives |

|

Note: An asterisk indicates that the firm supplies to UNFPA procurement. Where the firm is listed with more than one product line and is a UNFPA source, the product supplied is also marked with an asterisk. a GynoPharma was sold to Ortho Pharmaceuticals in summer of 1995. b Whitehall decided to discontinue the Today sponge because of the costs of bringing the plant up to U.S. Food and Drug Administration specifications. Sources: Frost and Sullivan. U.S. Contraceptive and Fertility Product Markets. New York, 1993. United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). 1993 Procurement Statistics. New York, 1993. |

|

for 1990 and 1992. Of the 11 U.S. firms competing in the U.S. oral contraceptives market in 1992, Ortho and Wyeth-Ayerst controlled 70 percent of total revenues, followed by Berlex (a Schering subsidiary), Syntex, Parke-Davis, and Mead Johnson (a Bristol-Myers Squibb subsidiary), with roughly comparable shares running around 4 to 6 percent each. The remainder was shared among the five other competitors. There is no expectation that the concentration of this subsector of the industry will change, largely because of the extent of the investment needed to develop new oral contraceptives and labeling requirements that are perceived as benefiting larger companies. Ortho, Wyeth-Ayerst, Organon, and Berlex (Schering AG) are likely to continue their market dominance with the newer progestin-based formulations as well.

The rest of the industry is similarly oligopolistic. Even though there are over 100 different brands of condoms on the market (Hatcher et al. 1994), Carter Wallace dominates with 60 percent of total revenues. There are just three competitors with diaphragm product lines and, again, Ortho got over half of 1992 revenues; Milex's share was around 40 percent. Ortho also gets half the revenues from the U.S. spermicidal preparations market, where there are six other competitors, one of which is Whitehall, like Ortho, part of American Home Products. Wyeth-Ayerst has the monopoly in the United States for the levonorgestrel contraceptive implant Norplant. Finally, the IUD line is very close to monopoly; until its sale to Ortho in summer 1995, GynoPharma was the market leader, with 94 percent of revenues. The IUD market is not likely to burgeon in terms of new entries since, as a very-long-term method that has been on the market for a long time, it generates a very modest margin of profit.

The international picture is also one of concentration. In the case of oral contraceptives, which account for the overwhelming bulk of all contraceptive revenues worldwide (over 80 percent in 1992), American Home Products and Johnson and Johnson still dominate but share the top of the worldwide OC market with the large European firms Schering AG and Organon, which increased their percentage share of sales between 1988 and 1992 (see Table 6-8). The four firms together accounted for 81 percent of all oral contraceptive sales worldwide in 1992, or $1.7 billion out of total worldwide sales of $2.1 billion. Four other large integrated firms—Searle (a Monsanto subsidiary), Syntex, Parke-Davis (a Warner-Lambert subsidiary), and Bristol-Myers Squibb—accounted for another $272 million, or 13 percent of sales. For all eight firms, oral contraceptive revenues were close to or well above the magic "$50 million-dollar market" figure; for seven other firms and miscellaneous "others," which shared the $133 million balance, that figure was much smaller and seems not to have constituted a major product line. There are, nevertheless, small firms which have evidenced commitment to engagement in new areas of contraceptive technology, notably Leiras of Finland, Gedeon Richter of Hungary, and Silesia of Brazil.

As noted at the outset of this chapter, the number of large pharmaceutical firms remaining in the research and development component of the contracep-

TABLE 6-7 Contraceptive Revenues (in millions of dollars), United States, 1990 and 1992, by Product Type and Company

|

Product |

1990 |

1992 |

|

Oral Contraceptives |

|

|

|

Ortho |

376.0 |

385.4 |

|

Wyeth-Ayerst |

306.7 |

343.7 |

|

Syntex |

69.3 |

62.5 |

|

Berlex |

59.4 |

62.5 |

|

GD Searle |

49.5 |

52.1 |

|

Parke-Davis |

49.5 |

62.5 |

|

Mead Johnson |

49.5 |

41.7 |

|

Others |

29.7 |

31.2 |

|

Subtotal |

989.6 |

1,041.6 |

|

Condoms |

|

|

|

Carter Wallace |

70.0 |

81.7 |

|

Schmid |

34.4 |

36.0 |

|

Ansell |

14.7 |

16.6 |

|

Others |

3.7 |

4.2 |

|

Subtotal |

122.8 |

138.5 |

|

Spermicides |

|

|

|

Ortho |

21.1 |

26.3 |

|

Whitehall |

9.9 |

8.6 |

|

Schmidt |

7.2 |

7.7 |

|

Others |

6.7 |

5.3 |

|

Subtotal |

44.9 |

47.9 |

|

Norplant |

0.0 |

40.1 |

|

IUDs |

|

|

|

GynoPharmaa |

15.5 |

21.2 |

|

Alza |

4.6 |

2.1 |

|

Subtotal |

20.1 |

23.3 |

|

Diaphragms |

|

|

|

Ortho |

2.1 |

2.0 |

|

Milex |

1.2 |

1.7 |

|

GynoPharmaa |

0.2 |

0.2 |

|

Subtotal |

3.5 |

3.9 |

|

Total (All product types) |

1,180.9 |

1,295.3 |

|

a GynoPharma and its IUD and diaphragm lines were sold in summer 1995 to Ortho Pharmaceuticals. Source: Frost and Sullivan. U.S. Contraceptive and Fertility Product Markets. New York, 1993. |

||

TABLE 6-8 Worldwide Oral Contraceptive Market, Sales 1988 and 1992 (in millions of U.S. dollars), by Company

|

|

1988 |

1992 |

||

|

Company |

Sales |

% Total |

Sales |

% Total |

|

Wyeth (American Home Products) |

452 |

30.2 |

610 |

29.2 |

|

Ortho (Johnson & Johnson) |

392 |

26.2 |

458 |

21.9 |

|

Schering AG |

244 |

16.3 |

372 |

17.8 |

|

Organon (Akzo) |

129 |

8.6 |

245 |

11.7 |

|

Searle (Monsanto) |

70 |

4.7 |

86 |

4.1 |

|

Syntex |

90 |

6.0 |

71 |

3.4 |

|

Parke-Davis (Warner-Lambert) |

42 |

2.8 |

69 |

3.3 |

|

Bristol-Myers Squibb |

30 |

2.0 |

46 |

2.2 |

|

Boehringer Ingelheim |

9 |

0.6 |

19 |

0.9 |

|

Menarini |

3 |

0.2 |

13 |

0.6 |

|

Polifarma |

0 |

0.0 |

13 |

0.6 |

|

Gruenenthal |

6 |

0.4 |

13 |

0.6 |

|

Rugby Labs |

4 |

0.3 |

10 |

0.5 |

|

Magnafarma BV |

0 |

0.0 |

8 |

0.4 |

|

Upjohn |

3 |

0.2 |

6 |

0.3 |

|

Others |

22 |

1.5 |

52 |

2.5 |

|

Total |

1,496 |

98.5 |

2,090 |

97.5 |

|

Source: Syntex data (I.M.S. data provided by Vector Fund Management, Deerfield, IL, 1995). |

||||

tives industry is very small: Ortho in the United States and Organon and Schering in Europe are the primary participants. Wyeth-Ayerst is engaged principally in R&D activities limited to modifications of implant technologies, and Merck, which has not been involved in contraceptives for decades, is sponsoring some research in immunologic contraception under a limited agreement with the University of Connecticut Medical Center.

The current picture of industry participation in contraceptive research and development is largely a continuance of the pattern of collaborative effort established in Stage III. These are typically with the public sector (primarily NIH/ NICHD [National Institute of Child Health and Development] and WHO/HRP [the World Health Organization's Human Reproduction Programme]); with a nonprofit entity which receives substantial infusions of public funds, for instance, the CONRAD program and Family Health International (FHI); or with a university partner. Partnerships between large and small firms are very few; at least, given information that is in the public domain, the big pharmaceutical firms remaining in contraceptive R&D appear to have no more than one or two such relationships (see Table 6-9). Furthermore, most of the products that are the

TABLE 6-9 Recent Industrial Involvement in Contraceptive Research and Developmenta

|

For-profit Companies |

Product |

Not-for-profit Partner(s) |

Other For-profit Partner(s) |

|

Advances in Health Technology |

mifepristone |

|

|

|

Allendale Labs |

Nonoxynol-9 film with benzalkonium chloride film |

CONRAD |

|

|

Alphatron (previously Ovabloc Europe) (Netherlands) |

Vas occlusion with silicone plug |

WHO/HRP AVSC |

|

|

AM Resource |

Bactericidal gel |

NIH: NICHD |

|

|

Apex Medical Technologies |

Nonlatex condoms |

NIH: NICHD |

London International Group |

|

Apothecus |

Vaginal film |

WHO/HRP NIH: NIAID FHI |

|

|

Aphton |

hCG immunocontraceptive |

WHO/HRP |

|

|

Applied Medical Research, Ltd. |

Estrogen-free minipill (B-Oval) containing melatonin and norethindrone (a progesterone) |

Dutch government |

|

|

Baxter |

Nonlatex condoms |

|

|

|

Bioself Distribution (Switzerland) |

Basal body temperature thermometer |

|

|

|

Biosyn |

Vaginal microbicides (spermicide C31 G: protection from conception, STDs) |

NIH: NICHD CONRAD University of Pennsylvania |

|

|

Biotech Australia |

Work with inhibin as component of hormonal contraception for both men and women |

|

|

|

For-profit Companies |

Product |

Not-for-profit Partner(s) |

Other For-profit Partner(s) |

|

Biotechnology General (formerly Gynex) |

Contraceptives, sublingual formulations |

|

|

|

Biotek |

Long-acting spermicide suppository; new nonoxynol-9 formulations |

NIH: NICHD Population Council CONRAD |

|

|

BKB Pharmaceuticals |

Emergency contraceptive (CDB 2914) |

NIH: NICHD RTI |

|

|

Cabot Medical |

Silicone rubber ring (Fallope) |

|

|

|

Cilag AG (Germany) |

Combined oral contraceptives |

|

|

|

Columbia Labs |

Sustained release formulations of spermicides, natural progesterone |

NIH: NICHD NIH: NIAID WHO |

|

|

Conceptus |

Non-surgical fallopian tube sterilization |

AVSC |

|

|

Curatek |

Vaginal gel (bactericidal) |

|

|

|

Cygnus Therapeutics |

Contraceptive patch 7-day contraceptive |

FHI |

Johnson & Johnson |

|

Endocon |

Biodegradable implant (Annuelle/NET) |

CONRAD FHI |

Wyeth-Ayerst |

|

Female Health Company (formerly Wisconsin Pharmacal) |

Female condom (Reality) |

CONRAD FHI |

|

|

Femcap Inc. |

Cervical cap |

CONRAD FHI |

|

|

Gynetics |

Combined oral contraceptives |

|

|

|

Integra |

Spermicide with polymer barrier |

CONRAD |

|

|

For-profit Companies |

Product |

Not-for-profit Partner(s) |

Other For-profit Partner(s) |

|

Jenapharm (Germany) |

Antiprogestins other than mifepristone |

RTI |

|

|

Leiras Pharmaceuticals (Finland) |

Progestin-releasing IUD (Levonova); levonorgestrel-IUD (Mirena); implants (Norplant) |

WHO/HRP Population Council |

|

|

Lidak |

n-Docosanol |

|

|

|

London International Group (UK) |

Nonlatex condoms |

NIH: NICHD |

|

|

Magainin |

Spermicide/microbicide |

NIH: NICHD (have CRADA) |

|

|

Medisorb (formerly Stolle Research) |

New injectable formulations using biodegradables, microspheres |

CONRAD FHI |

Ortho |

|

Merck |

Immunocontraception |

NIH: NICHD University of Connecticut Medical Center (3-yr. agreement with principal investigator) |

|

|

Novovax |