3

Cold-Weather and High-Altitude Nutrition: Overview of the Issues

Eldon W. Askew1

INTRODUCTION

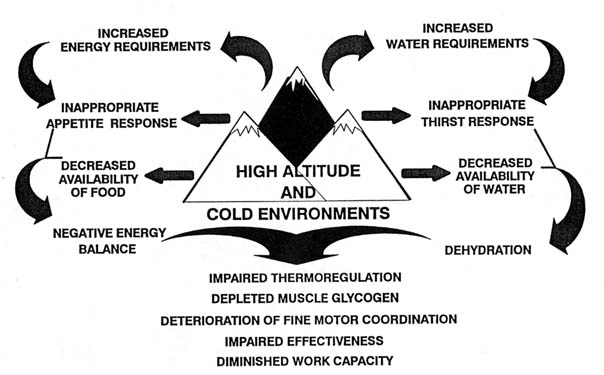

Climatic extremes can exert profound influences on human physiology (Figure 3-1). How well humans adapt to these environmental stresses ultimately determines the degree of success they achieve in these difficult and often hostile environments. Success or failure may be influenced by how well the body responds to the challenges of maintaining homeothermia and work output. The body's metabolic response to cold and hypoxia can be either augmented by proper nutrition or impaired by inadequate nutrition (Askew, 1994).

The many similarities between cold and high-altitude environments (Table 3-1) make them suitable to address in the same workshop and book. This is not without precedent. The Arctic Aeromedical Laboratory held a symposium,

TABLE 3-1 Similarities and Dissimilarities Between Cold and High-Altitude Environments

|

Similarities |

Dissimilarities |

|

Low ambient temperatures |

Lower atmospheric oxygen tension at high altitude |

|

Diuresis, at least initially |

Usually greater anorexia and hypophagia at high altitude |

|

Increased energy requirements for work |

Fat tolerated well in the cold |

|

Lack of water except for ice and snow |

Fat not tolerated well at high altitude |

|

Difficult to prepare food |

|

|

Carbohydrate is tolerated well |

|

|

Protein not particularly advantageous |

|

Arctic Biology and Medicine: The Physiology of Work in Cold and High Altitude, at Fort Wainwright, Alaska (Helfferich, 1966). General Ross, the Yukon Commander, gave the welcoming address at this 1966 meeting of environmental physiologists, and his words regarding the military relevancy of cold and high-altitude research are as appropriate now, as then:

Military interest is expanding to areas that were once considered uninhabitable and forbidding, such as the Arctic. The geopolitical importance of the Arctic basin and the Arctic mountainous area necessitates much greater knowledge and special understanding of these areas…In light of the constantly changing military requirements, it is singularly important for us to understand the physiological responses and limits of man to these unusual stresses in order to utilize human capabilities maximally in the accomplishment of our military mission. It is also necessary for us to understand what measures can be taken to improve the functional capacity of military personnel in these adverse and hostile environments…(Helfferich, 1966, p. 1).

PREVIOUS SYMPOSIA

During the 1950s and 1960s there were a number of symposia or conferences on environmental physiology, usually sponsored or cosponsored by the U.S. Armed Services (Table 3-2). These excellent reviews of environmental medicine came to an end after the mid 1960s, perhaps due to a lack of military sponsorship. Their end also coincided with a gradual decline in the amount of contract funds available from the Armed Forces to support extramural research of this nature.

Historically, a significant proportion of environmental medicine research during the World War II and Korean War eras was conducted in government-supported civilian research institutions such as the Universities of Illinois, Minnesota, Washington, California, Hawaii, Colorado, and Alaska, and in the Fatigue Laboratory at Harvard University. In the 1970s and 1980s the emphasis began to shift from extramural to intramural research, and the Armed

TABLE 3-2 Conferences and Symposia on Environmental Physiology in Cold and/or High-Altitude Environments

|

Conference/Symposium Title |

Year |

Location |

Reference |

|

Nutrition Under Climatic Stress |

1952 |

Washington, DC |

Spector and Peterson, 1952 |

|

Cold Injury |

1958 |

U.S. Army Medical Research Laboratory, Ft. Knox, KY |

Horvath, 1960 |

|

Man Living in the Arctic |

1960 |

U.S. Army Quartermaster Research and Engineering Center, Natick, MA |

Fisher, 1961 |

|

Nutritional Requirements for Survival in the Cold and at High Altitude |

1965 |

Arctic Aeromedical Laboratory, Ft. Wainwright, AK |

Vaughn, 1965 |

|

The Physiology of Work in Cold and High Altitude |

1966 |

Arctic Aeromedical Laboratory, Ft. Wainwright, AK |

Helfferich, 1966 |

|

Biomedicine Problems of High Terrestrial Elevations |

1967 |

U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, Natick, MA |

Hegnauer, 1969 |

Forces' laboratories began to conduct the majority of their environmental research in military facilities. The establishment of the U.S. Army's altitude research facility at the summit of Pike's Peak, Colorado in 1966 and the acquisition of the mission for cold research from the Air Force's Arctic Aeromedical Laboratory by the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine (USARIEM) in 1968 contributed to the trend toward intramural research. Whether this change in emphasis away from extramural research funding was due to a shift in military research strategies, a constrained military research budget because of the Vietnam conflict, or a decline in academic institution research interest in environmental nutrition and medicine, is not entirely clear. Ancel Keys, Director of the Laboratory of Environmental Hygiene at the University of Minnesota, commented on what may have been the beginning of the schism between academia and the military regarding scientific interest in nutrition research at a symposium held at the National Academy of Sciences in 1952:

It is appropriate to ask why, in general, the scientists of our country have been rather reluctant to engage in research directed toward problems of military subsistence. For it is a fact that many nutritionists may be willing, occasionally, to act on advisory boards and committees and to attend meetings like this symposium, but the amount of research they are carrying out is small.

Most scientists of real ability and worth are such because they are irresistibly attracted to gaining knowledge of a permanent nature…he feeds his vanity on the thought that his research has universal meaning…and that he is at grips with something more durable than this year's specifications for a combat ration…This means writing articles that he hopes will be applauded, commanding the attention of his fellows…a succession of purely practical researches directed toward changing problems of military subsistence, no matter how good, will not serve these ends…The answer is that every research program and project must carry with it the prospect of some real scientific advance…there must be provided opportunities for enlarging the scientific horizon of the field, for testing basic theories, for formulating new truths of general application (Keys, 1954, p. 199).

The ''writings on subsistence" of those talented and dedicated scientists of the not-so-distant past should be applauded. Their credit is long overdue. In retrospect, their ideas have lived on and formed the origins of the 1993 Workshop on Nutrient Requirements for Work in Cold and High-Altitude Environments, on which this book is based. The work of such university-affiliated scientists as Adolf, Keys, Mitchell, Horvath, Johnson, Sargent, Belding, Buskirk, and other civilian academic scientists too numerous to name, has achieved an important place in the nutrition literature.

Although it is difficult to explain the rather abrupt cessation of environmental medicine symposia sponsored by the Armed Forces, it is worthwhile to note that USARIEM in Natick, Massachusetts has begun to resume meetings of this nature in the form of workshops hosted by the Committee on Military Nutrition Research (CMNR) of the Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine, National Academy of Sciences. These workshops are narrow in focus and limited to a small group of civilian and military scientists who have expertise that can be focused on relevant practical scientific problems from a military standpoint. Publications of the National Academy Press provide the Department of Defense Food Program and the Surgeon General of the U.S. Army with comprehensive summaries of recent scientific literature, advice on specific scientific questions of military application and importance, and recommendations for future research in military nutrition. They also contribute to the preparation of U.S. Armed Forces environmental medicine "pocket guide deployment manuals," which are prepared by the USARIEM to assist soldiers and their commanders in conducting field operations in hot, cold, and high-altitude environments (Glenn et al., 1990; Thomas et al., 1993; Young et al., 1992).

The most recent workshop that focused on environmental extremes, Nutritional Needs in Hot Environments, was held during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. The resulting report (IOM, 1993) provided the Armed Forces with a comprehensive review of nutritional requirements in hot environments. Fluid requirements for work in the heat were addressed at a previous workshop sponsored by the CMNR in 1990 (IOM, 1991).

This book summarizes the advancement (or lack thereof) of knowledge of specific nutrient requirements as influenced by cold and high altitude,

particularly since the mid 1960s. The ultimate goal is to contribute to the design of rations and ration supplements that will permit more efficient soldier performance in cold and high-altitude environments.

Much of the scientific literature on cold and high-altitude nutrition has come from observations made by explorers. Although many of these reports are reliable and carefully conducted, their direct application to military operations may not be warranted. Soldiers are not necessarily of the same ilk as explorers. Sir George Hubert Wilkins, famed explorer of the Arctic and Antarctica, who made the first air flight over the North Pole and the first submarine voyage under the arctic ice, remarked:

Food problems to be met by explorers differ widely from those of the Armed Forces…men on an arctic expedition have been selected because of their interest in the area and in the work they must do. They are generally the type of men who eat to live rather than those who live to eat. They are not greatly concerned about their food except that it must give them the nourishment they require (Wilkins, 1954, p. 102).

PREVIOUS MILITARY RESEARCH: THE POLE MOUNTAIN WYOMING WINTER PROJECT

Because humans inhabit all the climatic regions of the Earth, there has always been considerable interest in both human genetic adaptations and cultural traditions that enhance survival, particularly in environmental extremes. The diet of humans living in different climates varies greatly, which raises the question whether the diet varies primarily due to the availability of food in the area, or because certain foods impart unique advantages to life in that climate.

For years, scientists have been intrigued with the possibility that humans select foods and acquire food habits that will help them adapt to their environment and combat climatic stress (Mitchell and Edman, 1949). Interest in foods and nutrients to combat environmental climatic stress peaked during World War II and continued into the postwar years.

Following World War II, scientific understanding of the roles of vitamins in the regulation of metabolism was clarified, and there was considerable research interest in these relatively new "glamour nutrients." The concept of vitamin supplementation to combat climatic stress arose and became the subject of much scientific debate. Some preliminary evidence suggested that when severe demands or stresses are placed on individuals (such as soldiers), their ability to withstand such stress might be improved by the administration of very large amounts of certain vitamins, particularly the water-soluble vitamins (Dugal, 1954; Ralli, 1954). Although not all investigators believed that excess vitamin intakes would improve human tolerance to cold (Glickman et al., 1946), by 1952, the body of evidence supporting this view was "…impressive enough to cause the Research and Development Board of the

Surgeon General's office and its consultants to pose the question of whether the concept might be applicable in certain military situations" (Medical Nutrition Laboratory, 1953, p. 1).

Following this recommendation, the staff of the Medical Nutrition Laboratory (located then in Chicago) drew up a protocol for a cold-weather field study. It was quite an undertaking and became known as the Medical Nutrition Laboratory Army Winter Project: Vitamin Supplementation of Army Rations Under Stress Conditions in a Cold Environment—The Pole Mountain, Wyoming Study (Medical Nutrition Laboratory, 1953). The study was designed to answer the basic question: Will the functional abilities of the soldier in a cold environment be significantly improved by supplementation with large amounts of vitamin C and B-complex? The specific objective of the 2-month cold-weather field study was to determine the effect of supplementation with large amounts of ascorbic acid and B-complex vitamins on the physical performance of soldiers engaged in a high-activity program in a cold environment, both with and without caloric restriction. The study was conducted at Pole Mountain, Wyoming (elevation 8,300 ft [2,532 m]), from 2 January 1953 to 10 March 1953 with 86 military personnel as study participants. The control group (42 men) received a capsule containing 6 mg of ascorbic acid four times a day. The supplemented group (44 men) received four capsules that appeared to be identical to the control capsules, each containing: 10 mg thiamin, 10 mg riboflavin, 100 mg niacinamide, 80 mg calcium pantothenate, 40 mg pyridoxine, 2.5 mg folic acid, 4 µg of vitamin B12, and 300 mg ascorbic acid. The average daily temperature was 26°F (-3°C), with the wind chill making it much colder. To enhance the effect of cold, the outdoor clothing was restricted to "less than the amount required for comfort when inactive under the prevailing weather conditions" (Medical Nutrition Laboratory, 1953, p. 23).

The subjects maintained a program of high-level outdoor physical activity. Physical performance measurements were taken, including the Harvard step test, handgrip strength test, Army Physical Fitness Test, and forced marches. The decline in rectal temperatures during indoor and outdoor cold exposure was measured, and a group of psychological tests were administered.

Major findings of the Pole Mountain study showed no significant differences between groups for physical performance measures or psychological tests. There was, however, a significantly greater loss of body weight in the supplemented group, perhaps related to a significantly smaller decline in their rectal temperatures upon cold exposure. The conclusions from this study were as follows:

Under the conditions of this experiment, supplementation of an adequate diet with large amounts of ascorbic acid B-complex vitamins in men subjected to the stresses of high physical activity,…cold,…and caloric deficit did not result in significantly better physical performance than that of unsupplemented men (Medical Nutrition Laboratory, 1953, summary, p. 2).

This report recommended that Army rations used in cold weather did not need to be supplemented (beyond the then current values in the Recommended Dietary Allowances, NRC, 1948) with ascorbic acid and B-complex vitamins, and this basic recommendation has stood for 41 years since the study. However, it was also recommended that further studies be made on the effect of vitamin supplementation on the physiological and pathological response of human subjects to cold exposure. This recommendation has not been pursued to a significant degree by military or civilian scientists. Only a small amount of subsequent research has taken place between 1952 and 1993 on the topic of vitamin supplementation and thermoregulation.

GOALS OF THE 1993 WORKSHOP AND THIS BOOK

The 1952 workshop on Nutrition Under Climatic Stress proposed that the participants address six topics:

- practical problems of service operations under climatic stress,

- physiological responses of men to heat and cold,

- animal experimentation,

- human experimentation,

- summary of present knowledge, and

- survey of areas in which more research is needed.

This was a reasonable format in 1952 and also served the 1993 workshop on Nutrient Requirements for Work in Cold and High-Altitude Environments (on which this book is based). Speakers for the 1993 workshop addressed one or more of these topics in their presentations, but animal and human work were not treated as separate topics.

Speakers for the 1993 workshop also received the list of questions that were of particular interest to the Army and that were presented and addressed by the CMNR in Chapters 1 and 2 of this volume.

AUTHOR'S CONCLUSIONS

This brief historical review of cold and high-altitude issues relative to military operations illustrates that the Armed Forces traditionally have been aware of and keenly interested in the impact of these extreme environments on human performance. Nutrition has been viewed as a key factor for enhancing both physiological performance and morale during operations in these environments. Military interest in research on nutrition and human physiology in cold and high-altitude environments peaked during and after World War II and the Korean conflict, probably due to the extensive cold weather operations

that were conducted in these wars and the doctrinal and equipment shortfalls that were perceived. During the 1950s and 1960s civilian and military scientists jointly participated in several excellent environmental medicine conferences that were sponsored by the Armed Forces. It is apparent that many of the same concerns regarding physiological limitations to human performance in cold and high-altitude environments that were expressed by civilian and military scientists 30 to 40 years ago still exist today. Advances in technology, doctrine, and equipment have not eliminated the need for a better understanding of human physiology and nutritional needs in these environments that are still critical to current military operations. It is hoped that this conference and report will help document and update the advances that have been made in establishing nutrient requirements for work in cold and high-altitude environments and give direction to future research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The assistance of Sharon L. Askew and Deborah Jezior in the preparation of this manuscript is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

Askew, E.W. 1994 Nutrition and performance at environmental extremes. Pp. 455–474 in Nutrition in Exercise and Sport, 2d ed., I. Wolinski and J.F. Hickson, Jr., eds. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press.

Dugal, L.P. 1954 Acclimation to a cold environment. Pp. 70–81 in Nutrition under Climatic Stress, H. Spector and M.S. Peterson, eds. A report of the Committee on Foods, Advisory Board on Quartermasters Research and Development. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council.

Fisher, F.R., ed. 1961 Man Living in the Arctic. Proceedings of a conference at the Quartermaster Research and Engineering Center, Natick, Mass. A report of the U.S. Army Quartermaster Research and Engineering Command and Advisory Board on Quartermaster Research and Development. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council.

Glenn, J.F., R.E. Burr, R.W. Hubbard, M.Z. Mays, R.J. Moore, B.H. Jones, and G.P. Krueger. 1990 Sustaining health and performance in the desert: A pocket guide to environmental medicine for operations in southwest Asia. Technical Note 91-2. Natick, Mass.: U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine.

Glickman, N., R.W. Keeton, H.H. Mitchell, and M.K. Fahnestock 1946 The tolerance of man to cold as affected by dietary modifications: High versus low intake of certain water soluble vitamins. Am. J. Physiol. 146:538–558.

Hegnauer, A.H., ed. 1969 Biomedicine Problems of High Terrestrial Elevations. Proceedings of a symposium. Natick, Mass.: U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine.

Helfferich, C., ed. 1966 The Physiology of Work in Cold and High Altitude. Proceedings of a Symposium on Arctic Biology and Medicine. Ft. Wainwright, Alaska: Arctic Aeromedical Laboratory.

Horvath, S.M., ed. 1960 Cold Injury. Transactions of the Sixth (1958) Conference on Cold Injury at the U.S. Army Medical Research Laboratory, Ft. Knox, Ky. Montpelier, Vt.: Capitol City Press.

IOM (Institute of Medicine) 1991 Fluid Replacement and Heat Stress. A report of the Committee on Military Nutrition Research, Food and Nutrition Board. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

1993 Nutritional Needs in Hot Environments, Applications for Military Personnel in Field Operations. A report of the Committee on Military Nutrition Research, Food and Nutrition Board. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Keys, A. 1954 The coordination of research approaches. Pp. 195–200 in Nutrition under Climatic Stress, H. Spector and M.S. Peterson, eds. A report of the Committee on Foods, Advisory Board on Quartermaster Research and Development. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council.

Medical Nutrition Laboratory 1953 The effect of vitamin supplementation on physical performance of soldiers residing in a cold environment. Report #115. Chicago, Ill.: Medical Nutrition Laboratory.

Mitchell, H.H., and M. Edman 1949 Nutrition and Resistance to Climatic Stress with Particular Reference to Man. A report prepared for the Research and Development Branch, Office of the Quartermaster General. Chicago, Ill.: Quartermaster Food and Container Institute for the Armed Forces.

NRC (National Research Council) 1948 Recommended Dietary Allowances, Revised 1948. Reprint and Circular Series No. 129. Washington, D.C.: National Research Council.

Ralli, E.P. 1954 The effect of certain vitamins on the response of normal subjects to cold water stress. Pp. 81–90 in Nutrition under Climatic Stress, H. Spector and M.S. Peterson, eds. A report of the Committee on Foods, Advisory Board on Quartermasters Research and Development. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council.

Spector, H., and M.S. Peterson, eds. 1952 Nutrition under Climatic Stress. A report of the Committee on Foods, Advisory Board on Quartermaster Research and Development. Washington D.C.: National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council.

Thomas, C.D., C.J. Baker-Fulco, T.E. Jones, N. King, D.A. Jezior, B.N. Fairbrother, K.L. Speckman, and E.W Askew 1993 Nutrition for health and performance: Nutritional guidance for military field operations in temperate and extreme environments. Technical Note 93-3, AD 261 392. Natick, Mass.: U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine.

Vaughn, L., ed. 1965 Nutritional Requirements for Survival in the Cold and at Altitude. Proceedings of a Symposium on Arctic Biology and Medicine. Ft. Wainwright, Alaska: Arctic Aeromedical Laboratory.

Wilkins, H. 1954 Food problems in exploring the Arctic. Pp. 102–107 in Nutrition under Climatic Stress, H. Spector and M.S. Peterson, eds. A report of the Committee on Foods, Advisory Board on Quartermasters Research and Development. Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences/National Research Council.

| This page in the original is blank. |