World Population and Health

Lincoln C. Chen, M.D., M.P.H.

Takemi Professor of International Health, Harvard University School of Public Health

WORLD POPULATION CHANGE

This discussion reviews the state of the world's population, its changes, and its implications for world health in the 21st century. My argument is that much of the future is already here in terms of demographic change and the globalization of health. Demography is the study of the size, composition, and distribution of human populations. Although quantitative methods are employed, demography is also centrally concerned with the quality of human populations, such as their health status.

Carbon dioxide emissions on planet earth are fingerprints of human activities. Such fingerprints would show large cities, as in North America, forest fires in the Amazon, and gas fires associated with petroleum production in the Middle East. For the first time in history, our human species has the technological capability to alter irreversibly our geophysical environment. These productive and consumptive patterns have generated remarkable wealth in some countries, although the wealth is concentrated mostly in three major regions—North America, Western Europe, and East Asia. There is a mismatch between wealth and where the world's people reside—overwhelmingly in the poorer regions of China, South Asia, and parts of Africa and Latin America.

In this our 20th century, world population experienced an unprecedented increase, from 1.7 billion in 1900 to more than 6.0 billion by the year 2000. Although forecasts about the future can reflect either "mumbo-jumbo" fortune-telling or statistical probabilities, population projections are neither, but are based upon assumptions about continuations of past trends modified according to assumptions about future changes in birth and death rates. The population projections performed by the United Nations, the World Bank,

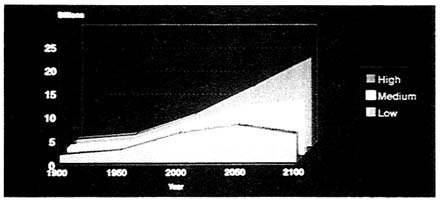

Figure 1 Population projection variants, 1900–2100.

and the U.S. Bureau of the Census all generate, however, remarkably similar demographic futures, as shown in Figure 1. By the end of the 21st century, we can expect a world population anywhere from about 8 billion to nearly 20 billion, depending on high, medium, or low assumptions of slow, medium, or very rapid reductions of human fertility. In these projections, mortality is assumed to continue its long-term secular decline—not an altogether safe assumption given the many human crises we are experiencing around the world. The annual number of new additions to planet earth is now peaking at about 90 million, and although this growth will continue for another decade, it will decline steadily throughout the next century. The peak rate of growth of the world's population was about 2.1 percent per year around 1970, having declined to today's rate of 1.6 percent. The net increment of population increase today is equivalent to adding one new Mexico or three new Canadas each year to the world's total population.

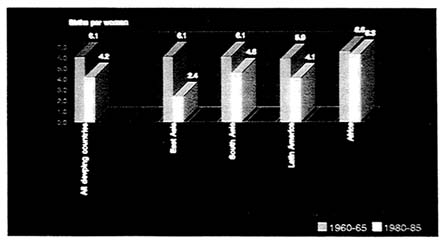

World population growth reflects a remarkable decline in fertility in the developing world, from an average of six children to four children between 1965 and 1985 (Figure 2). An unprecedented pace of decline has been experienced in much of Asia and Latin America. Slower declines were witnessed in South Asia and the Middle East, while little or no decline has been experienced in sub-Saharan Africa, although there is evidence that fertility has finally begun to decline in about four African countries. Throughout North America and Western, Central, and Eastern Europe, fertility has been near or even below replacement. The fertility declines have been associated with a marked increase in the prevalence of contraceptive use, from 9 to 45 percent of all eligible couples in the developing world.

Our demographic future over the next 25 years appears to be already with us. We will definitely have more people in the world, in large measure because of "population momentum," which is built-in growth due to reproduction among children already born. In other words, even if all couples were to achieve replacement fertility immediately, the youthful age structure of the world's population would still generate future growth because the

children already born will move through their reproductive years over the next three decades.

We will also have changing population compositions. Some have called the 20th century the "American century," in comparison to the 19th century—the "British century." The 21st century is likely to be the "Asian century" because of the shift in the gravity of people and wealth to East Asia, a process well under way at the close of this century. Whereas Europeans and North Americans constituted 34 percent of the world population in 1900, they will constitute only 14 percent by the year 2100. Asia's share of half the world's population will remain steady, but very large proportionate increases will come from Africa and Latin America. Another aspect of compositional change will be the aging of populations. High-fertility developing populations have a youthful (triangular) age structure in comparison to low-fertility industrialized countries, which have a more elderly (rectangular) age structure. In all countries, because of declining fertility, populations will continue to become more aged.

Finally, world populations will demonstrate changing geographic distributions. Rapid urbanization will translate into megacities throughout the world, especially in developing countries. Urbanization will be accelerated in part by continuing rural–urban migration. International migration also can be expected to accelerate in the 21st century. As described later, international migration may develop into a most important demographic feature of the 21st century.

DEMOGRAPHY IN THE UNITED STATES

High-, medium-, and low-variant projections of the U.S. population into the 21st century result in population sizes between 300 million and 400 million. Here, assumptions about rates of growth are generated mostly by dif-

Figure 2 Fertility trends in the developing world, by region.

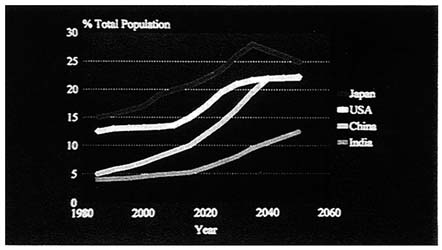

Figure 3 Percentage of population aged 65 and over. SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of the Census.

ferent levels of immigration, not fertility. Rather than population size, it is age structure that will experience the most pronounced change. Figure 3 shows the proportion of the population over age 65 years in the United States, Japan, China, and India. By the year 2020, the United States will have more than 20 percent of its population older than 65 years, higher than today's most aged society, Sweden, at 18 percent. Japan and China, the latter with its one-child family policy, will experience similar aging processes. Among the aged, the proportion of those who are "very old" (over 75 or 80) will also increase. Aging raises concerns not only about the economic and social aspects of care for the elderly, but also about the ratio of elderly dependents to productive adults, whose caring responsibilities will shift increasingly from children to the elderly.

A third demographic feature of America's population change will be migration. Population redistribution away from the Northeast to the Southwest will likely continue. Equally pronounced will be a shift in the ethnic composition of Americans due to immigration. By assuming high rate of immigration, the ethnic composition of Americans from 1950 to 2050 with generate two striking changes. Anglo Americans will be a minority group and the Hispanic population will grow to become almost twice the size of the black population in the second half of the next century. Medium and low levels of immigration will mute some of these changes, but the directions will remain constant.

HEALTH: THE WORLD AND THE UNITED STATES

Demographic change, worldwide and within the United States, will powerfully affect all aspects of the quality of life—the environment, food, the economy, schools, jobs, and health. In world health, this century has witnessed a remarkable revolution. Unprecedented progress has been enjoyed

Table 1. Epidemiologic Transitions

|

First Generation of Diseases |

|

Common Childhood Infections |

|

Malnutrition |

|

Reproductive Risks |

|

Second Generation of Diseases |

|

Cardiovascular |

|

Oncotic |

|

Degenerative |

|

Third Generation of Diseases |

|

Environmental Threats |

|

Air, water, chemical |

|

Ozone depletion, global warming |

|

New/Emerging Infections |

|

HIV/AIDS, Ebola virus, plague |

|

Tuberculosis, dengue, cholera |

|

Sociobehavioral Pathologies |

|

Violence |

|

Drug abuse |

|

Mental and psychosocial illness |

by all countries, industrialized and developing. In terms of health, our grandparents lived in an entirely different health world from that we enjoy today. It is worth recalling that the infant mortality rate in New York City at the beginning of this century was higher than it is today in Bangladesh. Health advances, however, have been uneven, with many countries, especially the economically poor and politically unstable, being left behind. Infant mortality rates still vary more than a log order between the best and worst countries. The positive picture of progress, therefore, is counterbalanced by concerns about health inequity and health diversity between and within countries.

The heterogeneous health situation is due to the complex epidemiologic and health transitions taking place around the world. Table 1 shows how the epidemiologic pattern of the causes of death changes as life expectancy improves. At low life expectancies, poverty-linked causes of death due to common childhood infections, malnutrition, and risks associated with childbearing predominate among women and children. As life expectancy is extended, affluence-related cardiovascular, oncotic, and degenerative diseases begin to predominate among adults and the elderly.

Some have hypothesized that we are entering an era of a "third wave" of environmental, infectious, and behavioral disease threats that are shared by all societies, rich and poor alike. Even as we have yet to overcome the first generation of environmental health problems due to lack of clean water and sanitation, we are confronting new environmental problems of ozone depletion, global warming, and the safe disposal of toxic waste. Because ecologi-

cal fragility and population growth threaten the food balance sheet, the age-old question arises of how many people the world can feed. Recently, Joel Cohen at the Rockefeller University reviewed estimates of the earth's capacity to feed its people. He found more than 65 studies over the past centuries that estimated the earth's food production capacity as feeding anywhere from 1 billion to 1,000 billion people, with most estimates ranging from 5 billion to 10 billion. In the review, he underscores that this may be the "wrong question," because the number of people that can be fed depends upon human choices in terms of the quality, style, distribution, and pattern of human consumption. In other words, this issue is not simply ecological but rather moral and within the choice of human agency.

The Institute of Medicine at its 25th anniversary annual meeting underscored concerns over new and emergent infectious diseases, such as HIV/AIDS, Ebola virus, cholera, plague, dengue fever, and the development of multiple resistant organisms. There are, furthermore, a host of sociobehavioral pathologies, such as violence, drug abuse, and mental illness.

This third wave of disease threats may reflect the emergence of health as part of the process of globalization. Acceleration in international trade of goods and services, rapid flows of financial capital through the global private marketplace, the communications and technology revolutions, and migration both temporary and permanent may be generating new transnational health linkages that will create world health interdependence, just like economic interdependence. Transnational connections in health imply that health threats no longer can be contained by national frontiers; most diseases do not require passports to travel. National sovereignty in health is eroding rapidly. Transnationalization, we already recognize, will carry international health processes across national borders. The 1991 cholera outbreak in Peru was probably transmitted by ships moving goods from Asia to Latin America. With the North American Free-Trade Agreement, nursing homes for elderly Americans may find the lower labor and energy costs in Mexico attractive. Communications and transport are compressing distance and time. More than 500 million air travelers cross national frontiers annually, and international migration—family reunification, economic migration, refugees—is likely to grow given the porous movement of investment, production, and consumption. An increasingly literate public will understand the science of health better than at any time in human history, propelling public health to develop its third "public" dimension—public governmental service, population approaches to public health problems, and public agency of its own health. International cooperation, therefore, may become even more essential for national health.

CONCLUSION

I close by underscoring three dimensions of world health and population in the 21st century. First, health is both part of the problem and part of the

solution to world population change. The unprecedented growth of human populations in the 20th century was due demographically to the very rapid decline of mortality in relation to fertility, especially in developing countries. Yet, as recently articulated at the Cairo population conference, the provision of basic reproductive and child health services and women's education and empowerment constitute the most effective approaches to population stabilization. Universal access to affordable, high-quality reproductive and child health services—contraception, control of sexually transmitted diseases including HIV/AIDS, maternal and child health—offers the most effective and humane approach to attaining good health, enabling couples to achieve smaller desired family sizes and accelerating the world's demographic and health transitions to stability and quality.

Second, America's health in the 21st century must wrestle successfully with equity between the young and the aged and among social and ethnic groups. The aging of America's population will have enormous social implications for family structure and care taking of the elderly, economic implications for health care costs, and will also affect our body politic. Imagine a voting population one third of whom are older than 65. President Clinton and Speaker Gingrich have been wresting with this phenomenon in recent debates over the future of Medicare and Social Security. The politics of health care access will also be accentuated by immigration and the changing ethnic composition of America's population, as the Anglo majority declines and Hispanic and other minority groups increase. How the poor and disadvantaged in the United States gain access to high-quality services, through programs such as Medicaid, is very much a part of this debate about national priorities and responsibilities.

Finally, America's health in the 21st century is already inextricably linked to world population and health. We are becoming part of a "global health village" because of health interdependence and the transnationalization of disease. Most health problems are commonly shared, and many health risks clearly have transnational properties. The imperative for international cooperation will intensify.

For the Institute of Medicine in its next 25 years, three questions are central: (1) How can America's powerful scientific capacity be shared with the rest of the world? (2) What can we learn from successes and failures from around the world? (3) How much isolated progress can we enjoy without parallel progress elsewhere? Health in America will not prosper if it cuts itself off from the wealth of scientific opportunities elsewhere, fails to learn from the successes and failures of others, and strives in isolation to advance health while others flounder. These are not purely academic questions; they are also practical and moral. I have no doubt that at its 50th anniversary celebration, the Institute will be able to report that its "2020 vision" has not only reacted to but led the world and the American public in addressing these questions for the sake of our common health.

DISCUSSION*

PARTICIPANT: How do global income disparities affect health?

DR. CHEN: We are witnessing global economic transformations in all countries. I think we must recognize that the private market, for all of its efficiencies, is not and can never be equitable. There needs to be an ethical basis and a social set of relationships underlying the equitable and efficient functioning of economies that are based on capitalism. We have not found a solution to that in the United States, as we search for our future, and the world is pursuing the same approach.

Now, there are conflicting data about what this means in terms of health conditions. On the one hand, there is a convergence in the rates of improvement of life expectancy across countries. Yet these data show a divergence in terms of capacity to command income between countries. So you have a diverging income stream and a converging life expectancy stream.

The best theory to explain this is ''disguised morbidity.'' Because of knowledge, we are more able to avert death, but we nevertheless carry heavier burdens of disease among those who are disadvantaged.

Second is the capacity of people with knowledge to protect themselves against mortality. I think that this is one of the real contributions of medical science in the 20th century. We can protect ourselves against mortality, but we cannot necessarily protect ourselves against sickness.

PARTICIPANT: What about cross-cultural values in shaping health in different cultures?

DR. CHEN: I certainly agree that the multiculturalism in the United States and internationally will pose many ethical dilemmas. Our technological capacity obviously is running far ahead of our moral and ethical consensus about how to deal with these questions, both domestically and internationally.

I am going to a workshop in February in Japan that will deal with Asian values and cultures with respect to health and population change in the next century. Some Japanese and Chinese, for example, feel that they have unique ways of viewing these issues.

I will mention two other dimensions very quickly. One is that there is a growing universalism in the recognition that good health is a human right, not just a privilege. This is something that I know is debated in the United States. We tend in American culture to view civil and political rights as human rights, but do not view socioeconomic matters, including health care, in terms of rights. Other cultures actually have more balanced views about civil or political and social or economic matters.

In your question, you were perhaps referring to the second dimension, which involves Sam Huntington's theory about the "clash of civilization and culture." In his theory, the future of world politics will not be a north–south or east–west clash, but a clash between large cultural civilizations.

PARTICIPANT: What are the differences between Asian and Western cultures in terms of care of the aged?

DR. CHEN: One difference is that, for example, Singapore, Japan, and China—historically and at the present—have made policies that they will go into the future with a family-based rather than institutionally based systems of nurturing and caring for the elderly. So they are not setting up institutionalized systems. They are counting on three-generational family residential capacity to manage the aged.

Now, this is fine if you are a man, but not if you are a woman. I gave a speech on this topic in Tokyo to an audience of Japanese men about 5 months ago. Actually, they took it quite seriously, because women are entering the work force in very large numbers and want to participate in the political, economic, and social life of the society. So the current policy, for example, in Asian society is to have a family-based system of care backed up by communities and institutionalized care. Yet, I am uncertain that Asian women, who would be required to manage the burden of care of the elderly, would be willing to accept such sacrifices. There has been very little work that I know of about the cost of technological intervention in the elderly age groups in these societies.

I might add that Asians, in the cultural area related to aging, feel very strongly that they have veneration and respect for the aged that has been lost in Western culture. However, in historical England, the same type of respect and veneration in the family toward the aged can be found, but Western culture has somehow lost these values. The Asians at the Japan conference, for example, were very sensitive to the fact that while something like this was lost in Western culture, it is not something that Asian cultures want to lose. I am a little skeptical, however, as to whether they will be successful with a family-based strategy.

PARTICIPANT: Could you comment on injury-related health problems?

DR. CHEN: We had a workshop at Harvard recently on the global burden of violence, and world homicide and suicide statistics were presented. Homicide rates are invariably higher among men than women around the world, but the higher female suicide rate in China was a puzzle. Actually, some of the Chinese who come from Beijing spoke to this question in terms of the ways in which young Chinese women are trapped into looking at their future without social choice and opportunity.