4

A Community Health Improvement Process

Many factors influence health and well-being in a community, and many entities and individuals in the community have a role to play in responding to community health needs. The committee sees a requirement for a framework within which a community can take a comprehensive approach to maintaining and improving health: assessing its health needs, determining its resources and assets for promoting health, developing and implementing a strategy for action, and establishing where responsibility should lie for specific results. This chapter describes a community health improvement process that provides such a framework. Critical to this process are performance monitoring activities to ensure that appropriate steps are being taken by responsible parties and that those actions are having the intended impact on health in the community. The chapter also includes a discussion of the capacities needed to support performance monitoring and health improvement activities.

In developing a health improvement program, every community will have to consider its own particular circumstances, including factors such as health concerns, resources and capacities, social and political perspectives, and competing needs. The committee cannot prescribe what actions a community should take to address its health concerns or who should be responsible for what, but it does believe that communities need to address these issues and that a systematic approach to health improve-

ment that makes use of performance monitoring tools will help them achieve their goals.

PROPOSING A PROCESS FOR COMMUNITY HEALTH IMPROVEMENT

The committee proposes a community health improvement process (CHIP) 1 as a basis for accountable community collaboration in monitoring overall health matters and in addressing specific health issues. This process can support the development of shared community goals for health improvement and the implementation of a planned and integrated approach for achieving those goals.

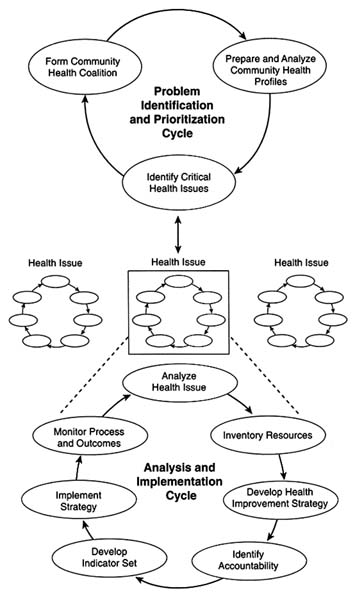

A CHIP would operate through two primary interacting cycles, both of which rely on analysis, action, and measurement. The elements of a CHIP are illustrated in Figure 4-1. Briefly, an overarching problem identification and prioritization cycle focuses on bringing community stakeholders together in a coalition, monitoring community-level health indicators, and identifying specific health issues as community priorities. A community addresses its priority health issues in the second kind of CHIP cycle—an analysis and implementation cycle. The basic components of this cycle are analyzing a health issue, assessing resources, determining how to respond and who should respond, and selecting and using stakeholder-level performance measures together with community-level indicators to assess whether desired outcomes are being achieved. More than one analysis and implementation cycle may be operating at once if a community is responding to multiple health issues. The components of both cycles are discussed in greater detail below.

The actions undertaken for a CHIP should reflect a broad view of health and its determinants. The committee believes that the field model (Evans and Stoddart, 1994), discussed in Chapter 2, provides a good conceptual basis from which to trace the multifactorial influences on health in a community. A CHIP must also

|

1 |

The CHIP acronym adopted for this report is not unique to the community health improvement process. In a health context, others use it to refer to community health information programs/partnerships/profiles. See, for example, the discussion of MassCHIP—the Massachusetts Community Health Information Profile—in Chapter 5. The committee anticipates that communities will adopt their own designations for their local community health improvement process. |

adopt an evidence-based approach to determining how to address a health issue. Evidence is needed not only to make an accurate assessment of the factors influencing health but also to select an appropriate process through which to make changes. For example, immunizations are an effective means of preventing some infectious diseases, but many children and older adults have not received recommended doses. Studies show that efforts to raise immunization rates should target both the barriers that keep people from using available immunization services and the provider practices that result in missed opportunities to administer vaccines (IOM, 1994b).

As envisioned by the committee, a CHIP can be implemented in a variety of community circumstances. Communities can begin working at various points in either cycle and with varying resources in place. The need to develop better data systems, for example, should not deter communities from using the CHIP framework. Using the process can focus attention on data needs and on finding ways in which they can be met. Participation from both the public and private sectors is needed, and leadership to initiate the process might emerge from either sector. The committee notes, however, that The Future of Public Health (IOM, 1988) suggests that public health agencies have a responsibility to assure that something like a health improvement process is in place. Thus, the committee recommends that local and state public health agencies assure that communities have an effective CHIP. At a minimum, these agencies should be CHIP participants, and in some communities they should provide leadership or an organizational home. Strong state-level leadership in places such as Illinois, Massachusetts, and Washington has helped promote progress at the community level.

The ongoing health improvement process must be seen as iterative and evolving rather than linear or short term. One-time activities, briefly assembled coalitions, and isolated solutions will not be adequate. A CHIP should not hinder effective and efficient operation of the accountable entities in the community that are expected to respond to specific health issues, and it must be able to accommodate the dynamic nature of communities and the interdependence of community activities. It should also facilitate the flow of information among accountable entities and other community groups and help them structure complementary efforts. Both community-level monitoring data and more detailed information related to specific health issues must feed back into the system on a continuing basis to guide subsequent analysis and

planning. This information loop is also the means by which a CHIP links performance to accountable entities among the community stakeholders.

In emphasizing the community perspective, the committee does not want to overlook the broader state and national contexts for community efforts. For example, health policymakers at the federal and state levels could consider community-level performance indicators when planning and evaluating publicly funded health services programs such as managed care for Medicaid populations. Community performance measures could also contribute to state management of federal block grants (e.g., Maternal and Child Health Title V grants or those under the Community Mental Health Services Block Grant program) and the proposed federal Performance Partnership Grants (PPGs) (USDHHS, no date).

Some state health departments are prominent participants in community-level health improvement efforts. In Massachusetts, for example, which has only one county health department, the state has taken a lead by establishing 27 Community Health Network Areas (CHNAs; see Chapter 3) to serve as the base for local health improvement activities (Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 1995). Elsewhere, state-level accreditation for local health departments can stipulate measurable targets for performance at the community level and require accountability for achieving targets during the term of accreditation. Illinois, for example, has implemented performance-based state certification of local health departments (Roadmap Implementation Task Force, 1990). Similarly, state agencies that license private-sector health plans or design Medicaid managed care programs have the opportunity to specify performance measures to be used to evaluate the services provided.

Origins of the Community Health Improvement Process

The committee's proposal for a community-based process for health improvement builds on many other efforts in health care, public health, and public policy, some of which are noted below.

The Health Care Sector

In the United States, proposals for collaborative community-wide efforts to address health issues date back at least to the early 1930s (Sigmond, 1995). One activity that emerged at this

time was comprehensive health planning (CHP), initially a voluntary effort to rationalize the configuration of personal health care facilities, services, and programs, often with a special emphasis on hospitals (Gottlieb, 1974). From the 1960s to the 1980s, the federal government supported formal programs for state- and community-level CHP as a strategy to improve the availability, accessibility, acceptability, cost, coordination, and quality of health care services and facilities (Benjamin and Downs, 1982; Lefkowitz, 1983). At the local level, however, CHP was hampered both by limited control over resource allocation and by its responsibilities to regulate the introduction of new health care facilities and programs (Sofaer, 1988). In addition, local ''ownership" of these activities was weakened by strict federal requirements regarding their organization and operation.

Nevertheless, the governing bodies of local planning agencies brought together multiple constituencies, including health care professionals and other "experts," consumers, and in a few cases, private-sector health care purchasers (Sofaer, 1988). CHP efforts also combined data on a community's health care services, epidemiology, and socioeconomic characteristics to identify high priority health problems. Indeed, some planning theorists explicitly based their approach on a model of the determinants of health (Blum, 1981) that might be considered an early version of the field model.

Concerns about the quality of health care stimulated measurement and monitoring activities. Evidence of widespread variations in medical practice patterns (e.g., Wennberg and Gittelsohn, 1973; Connell et al., 1981; Wennberg, 1984; Chassin et al., 1986), inadequate information about the outcomes of common treatments (e.g., Wennberg et al., 1980; Eddy and Billings, 1988), and evidence of marked variations across providers in the outcomes of treatment (e.g., Bunker et al., 1969; Luft et al., 1979) prompted increased concern about the effectiveness of care (e.g., Brook and Lohr, 1985; Roper et al., 1988) and a recognition of the importance of monitoring health care practices (e.g., IOM, 1990). Continuous quality improvement (CQI) techniques have been adapted from their origins in industry for use in health care settings (e.g., Berwick et al., 1990; IOM, 1990; Batalden and Stoltz, 1993), and clinical practice guidelines are providing criteria for assessing quality of care (e.g., IOM, 1992; AHCPR, 1995). The basic Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle used in CQI is being applied to community health programs (Nolan and Knapp, 1996; Zablocki, 1996). Health departments are also exploring their role in promoting the quality

of health care (Joint Council Committee on Quality in Public Health, 1996).

Community-oriented primary care (COPC), which gained increased attention in the 1970s and 1980s, starts from a health care provider perspective to bring together care for individuals with attention to the health of the community in which they live (Kark and Abramson, 1982; IOM, 1984). Although performance monitoring is not an explicit focus of COPC, this approach to health care emphasizes the importance of community-based data for understanding the origins of health problems.

The emergence of managed care and various forms of integrated health systems has been another factor that is broadening the health care focus from individual patient encounters to the health needs of a population. Enrolled members are generally the population of primary interest, but many of these organizations participate in activities serving the larger community such as violence prevention, immunization, AIDS prevention, and school-based health clinics. Some have formalized their commitment to community-wide efforts through mechanisms such as the Community Service Principles adopted by Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound (1996). Nationally, organizations such as the Catholic Health Association (CHA, 1995) and the Voluntary Hospitals of America (VHA, 1992) have adopted community benefit standards that call for accountable participation in meeting the needs of the community. The attributes of a "socially responsible managed care system," proposed by Showstack and colleagues (1996), also support involvement in community-wide health improvement efforts.

More generally, financial incentives are encouraging health care organizations to consider community-wide health needs. Nonprofit hospitals and health plans, plus the foundations established by provider organizations and insurers, are responding to the "community benefit" requirements needed to preserve their tax status. In addition, managed care plans are serving an increasing proportion of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries (Armstead et al., 1995), whose health may be adversely affected by problems not easily resolved in the health care setting (e.g., violence, poverty, social isolation). Because limited periods of eligibility for Medicaid benefits mean frequent enrollment and disenrollment, health plans may increasing see value in services that improve the health of nonmembers who might be part of their enrolled population in the future.

The Public Health Sector

Renewed interest in the 1970s and 1980s in a population- and community-based approach to health improvement was also reflected in both national and international activities in the public health arena (Lalonde, 1974; Ashton and Seymour, 1988), including the World Health Organization's Health for All by the Year 2000 program (WHO, 1985). The Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities movement, an international activity that emerged from the WHO and related programs, emphasizes building broad community support for public policies that promote health by improving the quality of life (Hancock, 1993; Duhl and Drake, 1995; Flynn, 1996).

In the United States, the first Healthy People report in 1979 helped draw attention to issues of prevention and health promotion (USPHS, 1979). In the early 1980s, the Planned Approach to Community Health (PATCH), was developed to enhance the capacity of state and local health departments to plan, implement, and evaluate health promotion activities (Kreuter, 1992; CDC, 1995b). It emphasizes collaboration both within the community and across federal, state, and local levels. Among other tools that have been developed to guide community health assessment activities is the Model Standards program, which was initiated in 1976. The most recent report, Healthy Communities 2000: Model Standards (APHA et al., 1991), outlines an 11-step community-based process for assessing health department and other community resources, identifying health needs and priorities, selecting measurable objectives, and monitoring and evaluating results of interventions.

Another approach, described in APEXPH: Assessment Protocol for Excellence in Public Health (NACHO, 1991), provides an eight-step process for assessing community health, assembling a community-based group through which to work, identifying and prioritizing issues of concern, and formulating a plan for responding. The APEXPH process is designed to begin with action by a local health department, but initial steps can also be taken by others in the community. The Healthy Communities Handbook (National Civic League, 1993b), developed under the auspices of the Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities initiative in the United States, reviews a process divided into a planning phase and an implementation phase. Steps in the planning phase include assembling a stakeholder coalition, (re)defining "community health," assessing influences on health in and beyond the community, reviewing health indicators and community capacities, identifying key per-

formance areas, and creating an implementation plan. The implementation phase includes monitoring activities and their outcomes.

In a recent survey of local health departments, 47 percent reported using Model Standards for planning activities, 32 percent reported using APEXPH, 12 percent reported using PATCH, and 6 percent reported using Healthy Cities (NACCHO, 1995). Many hospitals and health systems in the private sector also are using the APEXPH model to guide their health assessment activities (Gordon et al., 1996).

The interest in community-based health improvement activities also led to several major intervention trials targeting specific health problems. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), for example, sponsored projects in California (Farquhar et al., 1985), Minnesota (Mittelmark et al., 1986), and Rhode Island (Elder et al., 1986) to test a community-based approach to primary prevention of coronary heart disease. The National Cancer Institute initiated the Community Intervention Trial for Smoking Cessation (COMMIT) in 11 pairs of communities (COMMIT, 1991). Community-based approaches to health improvement also received support from foundations, as in the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation Community Health Promotion Grant Program (Tarlov et al., 1987).

Health Status and Performance Measurement

The committee's proposal draws from a variety of indicator development and performance measurement efforts. Healthy People 2000 (USDHHS, 1991), one of the most prominent, provides more than 300 national health promotion and disease prevention objectives. A smaller set of related indicators was endorsed for use in monitoring key elements of community health status (CDC, 1991). Many states have assembled their own objectives for the year 2000, and Healthy Communities 2000: Model Standards (APHA et al., 1991) specifically addresses how communities can adapt these and other related objectives to their particular circumstances. With stated targets to be achieved, objectives such as these are not only measurement tools but also statements of intended performance. In addition, more specialized assessments are being made such as monitoring the status of children at the state and local levels (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 1996; Children Now, 1996).

Interest in performance-based assessments of health care has

resulted in the development of "report cards" by some individual health plans and in a variety of nationally used and proposed health care indicator sets (e.g., Nadzam et al., 1993; NCQA, 1993, 1996a; AMBHA, 1995; FAcct, 1995). Individually, many health care organizations are monitoring performance for their internal quality improvement purposes and for tracking community benefit activities.

A focus on performance and outcomes also is central to ideas on "reinventing government" (Osborne and Gaebler, 1992; Gore, 1993; Hatry et al., 1994). The Government Performance and Results Act, for example, requires federal agencies to develop annual performance plans and to identify measures to assess progress (GAO, 1996). The proposals to implement PPGs for several health-related block grants would apply a similar approach to state grantees (USDHHS, no date). Some observers, however, caution against an overreliance on measurement in managing government activities, suggesting that many important tasks of government cannot be adequately quantified and that even if measurable may not be adequately insulated from political pressures (Mintzberg, 1996).

ADVANCING THE PROCESS

The process proposed by the committee reflects the need to combine features of these various activities to produce both a community-wide perspective and the performance measures that support accountability and inform further improvements. The current health planning and health assessment models provide a comprehensive community perspective but generally put less emphasis on the linkage between performance monitoring and stakeholder accountability than either the problem identification and prioritization cycle or the analysis and implementation cycle of the proposed CHIP. The quality improvement and performance measurement activities that have developed in the personal health care sector bring accountability for performance to the fore explicitly. They are, however, generally applied to specific institutions or health plan services for their members, not to activities of many entities responding to the needs of the entire population of a community.

Both community-wide and organization-specific performance measurement processes are needed to improve the health of the general population. Applying the field model perspective encourages consideration of the diversity of opportunities and agents, both inside and outside the usual "health" setting, that can con-

tribute to health improvement efforts. Although the committee's recommendations for operationalizing a CHIP are based on a variety of theoretical and practical models for community health improvement and quality assurance or performance monitoring in health care, public health, and other settings, the complete set of components of the committee's proposal has not yet been tested in communities. That will be an essential step in validating and improving the process.

PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION AND PRIORITIZATION CYCLE

As proposed by the committee, the problem identification and prioritization cycle has three main phases:

-

forming a community health coalition;

-

collecting and analyzing data for a community health profile; and

-

identifying high-priority health issues.

Community efforts can begin with any phase of the cycle. For example, the availability of data from the health department on various aspects of health status might spark action on a specific health issue before any community-wide coalition is established. Alternatively, efforts around a specific health issue might be the catalyst both for more broadly based activities and for the collection of additional health status data.

Form Coalitions

A long-term community coalition is an essential element in a CHIP. As noted in Chapter 3, a coalition is an organization of individuals representing diverse organizations, factions, or constituencies who agree to work together to achieve common goals (Feighery and Rogers, 1990). In the context of a CHIP, a coalition provides the mechanism for bringing together the community's stakeholders and accountable entities to develop a broad perspective on health needs and how they might be addressed.

Leadership is essential, both to initiate and to maintain a coalition. Many may look to the health department to play this role, but private-sector initiatives or public-private collaborations can also be the motivating force. The coalition's roles include obtaining and analyzing community health profiles, identifying critical issues for action, supporting the development of improvement

strategies, fostering the allocation of responsibility for health improvement efforts among community stakeholders, and serving as a locus of accountability for performance by those stakeholders.

A CHIP coalition should operate in the configuration that best suits a community's particular circumstances. The organizational structure may be more or less formal, and the name applied to the group may vary (e.g., committee, alliance, network). Some communities will already have coalitions that can assume a role in a CHIP. In other communities, an existing group may need to expand or adapt to a new role. In some cases, a local board of health might provide a starting point. If several groups are already in place, perhaps to address specific health issues or to represent specific segments of the community, they should establish a workable forum for collaboration with a more broadly based coalition and with each other. Once a coalition is in place, continuing CHIP cycles should provide an opportunity to bring into the process community constituencies that are not yet represented.

Coalition participants should include a community's major stakeholders and accountable entities. Among these groups are health departments and other public agencies, individual and institutional health care providers in the public and private sectors, schools, employers, insurers, community groups, the media, and the general public. Participants should include not only those groups that implement health improvement activities but also those that will have to collect, analyze, and report data used in the health improvement process.

Efforts must also be made to ensure that the general public has opportunities to participate and that public- and private-sector entities that may not traditionally have assumed a role in health issues are brought to the table. Because community health and resources are influenced by factors such as federal and state programs and policies and by private-sector activities such as corporate practices and accreditation standards, communities should consider how those perspectives can be represented in a coalition.

In the committee's view, inclusiveness is an important principle for these coalitions, but it recognizes that some activities may warrant attention from a more strategically focused group of participants. For example, public schools might be expected to play a more limited role in examining the health needs of the elderly than in smoking prevention and cessation programs for adolescents.

In most cases a coalition will function on the basis of willing participation and acceptance of shared responsibility for improving health in the community, but incentives to participate may vary among stakeholders. For health departments, participation in a coalition may be an effective way to meet responsibilities to the community under the three "core functions" of assessment, policy development, and assurance (IOM, 1988).

For some, participation in health improvement activities reflects a basic commitment to the well-being of the community (e.g., CHA, 1995; Showstack et al., 1996). Good will may not always be sufficient, however, and financial responsibilities cannot be ignored. It was noted in discussions at the committee's workshops that despite a commitment to efforts on behalf of the community's health in an organization such as the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound, it will be difficult to sustain that commitment unless other health care organizations accept a similar responsibility, including public reporting on the extent to which their efforts are meeting expectations (see Appendix C). Sigmond (1995) proposes that the private sector use the influence of accreditation to encourage community involvement. Standards could be established for participation in community partnerships.

Self-interest can also be an effective motivation. Employers, for example, may expect to benefit from reduced health care costs if community efforts can improve the health status of the workforce. Some coalition participants may find that they can use resources more efficiently because they can coordinate their activities with others working on similar projects. For some hospitals and health plans, economic incentives to participate may exist because of "community benefit" requirements for nonprofit tax status or contract provisions for Medicaid and Medicare providers. Participants should not, however, allow a coalition to become a means of furthering a particular constituency's goals at the expense of the best interests of the community.

Missouri has assembled a Community Health Assessment and Resource Team (CHART) specifically to provide technical assistance to the state's communities in coalition formation and other steps in the health improvement process (see Box 4-1). Additional discussion of coalition building appears in Chapter 3.

Collect, Analyze, and Publicize Community Health Data

Another phase of the problem identification and prioritization cycle is assessing the community's health status and health needs

|

BOX 4-1 MISSOURI'S COMMUNITY HEALTH ASSESSMENT AND RESOURCE TEAM Missouri has formed the Community Health Assessment and Resource Team (CHART) to provide resources and technical assistance to collaborative efforts to improve community health. CHART, based in the Missouri Department of Health, is itself a coalition, whose members are representatives of several health- and community-related agencies and organizations in the state. The members of the team bring expertise in community assessment and in development of strategies that improve community health. CHART also serves as a clearinghouse for information and resource materials for communities. The CHART partners include the Joint Committee on Health Care Policy and Planning, the Missouri Alliance for Home Care, the Missouri Association of Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons, the Missouri Chamber of Commerce, the Missouri Coalition for Primary Health Care, the Missouri Department of Health, the Missouri Department of Mental Health, the Missouri Department of Social Services, the Missouri Hospital Association, the Missouri Nurses Association, the Missouri Public Health Association, the Missouri State Medical Association, the Partnership Council, the Transition Advisory Team, and the University of Missouri—Columbia Health Services Management Department. Five "how-to" manuals for implementing local health assessment and improvement programs have been developed. They emphasize collaboration at the local level and provide state-of-the-art information on community health. The manuals are intended to be used, not in a "cookbook" approach, but rather as resources that should be adapted and revised over time to meet the needs of a continuing health improvement process in individual communities. Each manual contains explanatory text, as well as specially designed tools and worksheets. The tools and worksheets are intended to help communities organize their members, assess community health status, prioritize community health issues, and develop effective interventions for improving community health. Two of the manuals focus specifically on coalition issues. "Building a Community Health Coalition'' includes recommendations for securing a project sponsor, developing a team, defining leadership for the project, determining how to get the project started, and deciding on an overall project time frame. "Establishing a Foundation for a Successful Community Health Strategy" addresses defining the community, identifying key relationships, establishing a shared vision, refining team members' roles and responsibilities, and determining how to coordinate and use project resources. The other three manuals cover data collection and analysis issues in community health assessment, prioritizing community health issues, and developing and implementing a community health strategy. SOURCE: Missouri Department of Health (1996). |

by collecting and analyzing data and making that information available to inform community decision making. The committee sees a need, at a minimum, for these health assessment activities to produce a community health profile that can provide basic information about a community's demographic and socioeconomic characteristics and its health status and health risks. This profile would provide background information that can help a community interpret other health data. Comparing these data over time or with data from other communities may help identify health issues that require more focused attention. The committee's proposal for a basic set of indicators for a community health profile appears in Chapter 5. Where resources permit, states and communities may choose to develop a more extensive set of indicators.

The community health coalition should oversee the development and use of a health profile, but responsibility for data collection and analysis may lie with particular coalition participants that have resources suited to specific tasks. Health departments, in particular, have health assessment as a core function (IOM, 1988) and should, in the committee's view, be expected to promote, facilitate, and where necessary, perform the periodic health assessments needed to produce a community health profile. Profile updates should be produced regularly, and profile data should be compiled over time, ideally in electronic format, to facilitate assessment of trends. Annual updates may be possible for some measures, but others may depend on specialized data collection, such as the census, that occurs less frequently. The committee urges that all measures be updated at least once every five years and that more frequent updates be a goal.

Although some communities will have the resources and technical expertise to assemble a health profile on their own, many will not. The committee recommends that responsibility for assuring the availability of these data lie with state health departments. The state role includes collecting and publishing data and providing technical assistance to communities to use data and to collect community-level data that are not available from other sources. Working together, states and communities should seek to develop the information resources and technical skills that can support annual updates of most health profile measures. Some states, including Illinois, Iowa, and Massachusetts, are already making data available to communities electronically. Other states (e.g., Florida, Missouri, and New York) are beginning to publish some county-level data on the World Wide Web, which not only

facilitates access to this information for communities within the state but also allows other states and communities to use those data as points of comparison.

Data held in the private sector by health plans, indemnity insurers, employers, and others can also be valuable for community health assessments, and these organizations should provide appropriate data as part of their responsibility to the community, a position also taken by others (VHA, 1992; Showstack et al., 1996). To ensure access to essential data, however, the committee recommends that states and the federal government require that certain standard data be reported, including data on the characteristics and health status of enrolled populations, on services provided, and on outcomes of those services. In turn, these organizations should have access for their own decision-making purposes to other community data. This opportunity for mutual benefit should reinforce CHIP goals.

For all data collected and used for a community profile or other aspects of a CHIP, adequate safeguards for confidentiality will be essential. At the community level, ensuring that confidentiality is maintained will require special attention because of the small numbers of cases that many measures will produce. These issues are of continuing concern and have been discussed in the Institute of Medicine report Health Data in the Information Age (IOM, 1994a) and elsewhere (e.g., Gostin et al., 1993, 1996; Gostin and Lazzarini, 1995).

Discussions with the committee at its workshops emphasized the importance of involving both decision makers and community groups in assembling, reviewing, and responding to health data (see Appendixes C and D). A community coalition can undertake these collaborative assessments, but more extensive consultation with community constituencies may also be appropriate. The varied perspectives of these constituencies can produce a better understanding of points such as whether the results seem reasonable, whether there are gaps between findings and perceptions, and whether there are concerns that have not been identified through more quantitative approaches. The review can also identify areas of special interest to the community and generate guidance on how to treat sensitive issues. Involving the community and responding to its concerns may increase the community's interest in and support for health assessment activities. Experience in Seattle-King County, Washington, for example, suggests that making assessment data more readily available to the com-

munity can lead to increased support for these activities (see Appendix C).

Identify Critical Health Issues

The third phase of the problem identification and prioritization cycle is identifying those health issues that are of special concern to the community and determining which ones should be given the highest priority for additional attention. These priorities should reflect not only the judgment of public health agencies and health care providers but also the broader spectrum of community stakeholders, including the general public. A coalition should be able to bring many perspectives to these considerations, but views not represented within the coalition should not be neglected. A variety of specific techniques can be used for priority setting (e.g., see Krasny, 1980; Pickett and Hanlon, 1990; Vilnius and Dandoy, 1990; Chambers et al., 1996) and resources such as APEXPH (NACHO, 1991) can provide useful guidance to communities.

A health profile's standard epidemiologic data on morbidity, mortality, and health risk factors will influence but may not determine where a community's priorities lie. If a problem is of sufficient concern, small numbers of cases may be enough to motivate a community to respond (e.g., drug-resistant tuberculosis or adolescent suicides). Measures, from a community profile or other sources, that describe other aspects of the community's health-related environment, such as employment, housing, and transportation resources, can also be important in shaping priorities. The costs of possible interventions in relation to their potential benefits should be considered, and if available, formal economic analyses (e.g., cost-effectiveness studies) could help guide a community's priority setting.

A community may decide to respond to evidence that conditions have changed or that the community compares unfavorably with others or with a measure such as a Healthy People 2000 target. Benchmarks such as this can provide a basis for assess-

A benchmark is a standard established for anticipated results, often reflecting an aim to improve over current levels.

ing the acceptability of a health status level or the outcome of a health intervention.

Qualitative information should be considered as well. Information on the "who, what, when, where, and how" of a community provides a context for interpreting quantitative measures. A community coalition should encourage the use of mechanisms such as meetings with neighborhood or community groups to give those who may not consider themselves part of a coalition an opportunity to learn about and contribute to discussions regarding the community's health issues. Skilled meeting facilitators can help ensure that these discussions are effective, and the discussions may benefit from efforts to inform the community about the field model and the framework it provides for thinking about the determinants of health.

Other factors may also be operating when a community coalition decides which health issues will be targeted. Opportunities for an early "success" may be valued as a way to strengthen the coalition and increase support for the health improvement process. The coalition may find that an issue already being addressed by many groups provides an opportunity to build on available resources, including experience and prior commitment. In other cases, an issue that represents "neutral ground" for the various members of the coalition, because it is not a focus of competition for funding or does not target conflicting values, will be given priority. In Massachusetts, the CHNAs have found that considerations such as these influenced the selection of priority issues (D.K. Walker, personal communication, 1996). As a community gains experience with a CHIP, it will be possible to take up more challenging issues. The committee urges community coalitions to begin addressing specific health issues even if initial efforts are directed to topics that might not be seen by all as the "most important'' ones.

Communities should expect to develop, over time and as resources permit, a "portfolio" of health initiatives. The mix of initiatives in the community portfolio will change as a CHIP continues. Some may move ahead more quickly than others. If a community's circumstances change, issues once given a lower priority may assume greater importance. The community coalition must periodically review the health issue portfolio to ensure that appropriate issues are being addressed and that progress is being made or reasons for lack of progress are being examined.

A balance is needed between issues that lend themselves to quick, easily measurable success and those that require sustained

effort to produce a longer-term health benefit. Focusing only on the most difficult issues could undermine support for the health improvement process if progress is difficult to measure or will be evident only after many years. Important benefits of interventions that target critical developmental periods for infants and young children, for example, may not be evident until adolescence or adulthood. Communities and their coalitions should, however, guard against overemphasizing issues that are visible but have limited impact on community health. For example, "special event" immunization clinics will reach some children who have not received needed vaccinations but cannot provide the continuity necessary to ensure proper care for overall health and will not resolve the underlying problems in access to services or provider practices that contribute to underimmunization.

ANALYSIS AND IMPLEMENTATION CYCLE

Once an issue has been targeted by a community, the health improvement process proposed by the committee moves on to another series of steps:

-

analysis of the health issue;

-

an inventory of health resources;

-

development of a health improvement strategy;

-

discussion and negotiation to establish where accountability lies;

-

development of a set of performance indicators for accountable entities;

-

implementation of the health improvement strategy; and

-

measurement to monitor the outcome of efforts by accountable entities.

These steps are displayed and described as sequential (see Figure 4-1), but in practice they interact and are likely to be repeated varying numbers of times while a community is engaged in a particular initiative.

Analyze the Health Issue

A community, through its health coalition or a designated agent such as the health department, will have to articulate the specific issues of concern in the community and goals for a health improvement activity. An analysis of the health issue should ex-

amine the general underlying causes and contributing factors, how they operate in that specific community, and what interventions are likely to be effective in meeting health improvement goals. The committee encourages the use of a framework such as the field model (see Chapter 2) to guide the analysis so as to ensure that consideration is given not only to health care or health department issues but also to a broader array of factors, such as those in the social and physical environments. This approach is necessary to identify the strongest determinants of health or those that may present the most promising opportunities for strategic change. Sources such as APEXPH (NACHO, 1991) and PATCH (CDC, 1995b) can provide additional guidance and offer tools such as a "health problem analysis worksheet" that can be used with the field model framework.

Where the factors that influence health are well understood (e.g., disease protection provided by immunizations or the added risk of low-weight births from maternal smoking), the analysis should be able to help community stakeholders understand what kinds of health improvement activities may be useful and who in the community might be expected to assume responsibility for some aspect of health improvement. Expert advice can be especially valuable when the determinants of health status are less well understood. Such advice can help coalition participants, and the larger community, to interpret the available evidence and determine how the accepted "best practices" can be applied to meet the community's needs.

Inventory Health Resources

A community will also have to assess the resources that it can apply to a health issue. Within the community, these can include organizations, influence, expertise, and funding that can be applied to required tasks, as well as individuals willing to volunteer time and effort. Another type of community resource will be factors that operate (or could be developed to do so) as protective influences that can mitigate the impact of adverse conditions. For example, stable families appear to help overcome some of the health problems that might be expected in the lower-income immigrant population of New York City's Washington Heights/Inwood neighborhood (see Appendix C). Funding, technical assistance, and other forms of support may also be available from public- and private-sector sources outside the community. Tools such as APEXPH (NACHO, 1991) and the Civic Index (National

Civic League, 1993a,b) are available to assess community resources. APEXPH focuses in particular on the capacity of the local health department to perform a variety of functions important for health improvement activities such as building community constituencies, collecting and analyzing data, and developing and implementing health policy.

The experience of McHenry County, Illinois, described briefly in Box 4-2, illustrates one community's approach to a specific health concern.

Develop a Health Improvement Strategy

A health improvement strategy should reflect an assessment of how available resources can be applied most effectively to address the specific concerns associated with a health issue in a community. Several considerations should shape such strategies. Some actions can achieve short-term changes but may not ensure more fundamental improvements in health that can be seen only over a longer period. Interim goals for major health problems, such as risk reduction strategies, may help sustain a health improvement effort. If a community were interested in reducing cancer mortality, for instance, strategies might focus on a reduction in smoking initiation among teenagers and the implementation of workplace smoking restrictions as initial goals. Strategy development should also include consideration of the consequences of not taking any action.

Priority should be given to actions for which evidence of effectiveness is available. Evidence is needed not only that an action can be expected to have the desired health impact (e.g., immunization to prevent measles) but also that an effective form of implementation has been identified (e.g., reminders to providers that an immunization is due; e.g., Rosser et al., 1992). A source such as the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 1996) provides an authoritative review of evidence on specific clinical services. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is assisting a newly established task force in developing a similar report on "what works" in community-based preventive services (see Novick et al., 1995, for preliminary work in this area). Evidence from economic analyses (e.g., cost-effectiveness or cost-benefit analysis) should be considered as well. For many health issues, however, evidence for effective interventions will be limited, and communities are unlikely to have the expertise, funding, or time needed to conduct their own outcomes

|

BOX 4-2 ASSESSMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH ISSUES, RESOURCES, AND RESPONSES IN McHENRY COUNTY, ILLINOIS As part of the Illinois Project for Local Assessment of Need (IPLAN), McHenry County undertook a local health needs assessment and developed a community health plan, which was issued in 1994. Following the APEXPH process (NACHO, 1991), the Community Health Committee reviewed IPLAN data provided by the state health department on the county's sociodemographic characteristics, general health status, and specific health issues such as maternal and child health, chronic disease, infectious disease, environmental health, injury, and access to care. Additional data from other sources supplemented IPLAN information. Environmental health issues emerged as one of the county's priorities, and four specific concerns were identified: protecting groundwater supplies, limiting exposure to radon, preventing foodborne illness, and reducing pesticide exposure. Outcome objectives were established for each of these issues, for example: by 1999, reduce the number of additional community wells contaminated with volatile organic chemicals to fewer than five (baseline: 9 wells currently contaminated). A set of impact objectives addresses how the county expects to achieve its desired outcomes. For reducing contamination of wells, the impact objective is to develop a water management plan by 1997. Process objectives and intervention strategies were also identified, for example: convening a technical advisory committee on groundwater protection. A diverse collection of resources was identified as being available in the county to respond these environmental health concerns: schools, media, conservation agencies, the Farm Bureau, the Environmental Protection Agency, hospitals, master gardeners and garden clubs, local consulting agencies, physicians in private practice, the McHenry County Medical Society, the Mental Health Board, and the McHenry County Department of Health. SOURCE: McHenry County Department of Health (1994). |

studies or economic analyses. A community should not ignore these issues or the interventions under consideration, but it will have to consider carefully what actions can make the best use of its resources. Advice from experts can help a community coalition identify and interpret available evidence and design appropriate interventions.

The strategy development step should also include consideration of potential barriers to success that may arise in trying to

implement a strategy. Issues to consider include whether an intervention can or will be implemented; whether it will reach all who need it; and whether intended beneficiaries can or will take advantage of health improvement efforts. Early consideration of these questions may make it possible to recast the strategy to overcome anticipated problems.

Work done on the evaluation of "comprehensive community initiatives" points to the value of a thoughtful articulation of the "theory of change" embodied in an intervention strategy—how and why an intervention is expected to work (Weiss, 1995; Connell and Kubisch, 1996). Specifying intended long-term and intermediate outcomes and how they would be achieved can help clarify assumptions about the purpose and operation of an intervention and guide the selection of performance indicators. Connell and Kubisch (1996) suggest that this process can promote collaboration and commitment to the intervention and help clarify pathways of accountability.

Establish Accountability for Health Improvement Activities

Establishing accountability is a key to using performance monitoring in the health improvement process proposed by the committee. Specific entities must be willing to be held accountable for undertaking activities, within an overall strategy for dealing with a health issue, that are expected to contribute to achieving desired outcomes. The committee sees a collective responsibility among all segments of a community to contribute to health improvements, but each entity must accept individual responsibility for performing those tasks that are consistent with its roles, resources, and capabilities. (See Chapter 3 for additional discussion of these issues.)

Depending on the health issue and the community stakeholders involved, different approaches may be necessary to reach agreement on who will be accountable for what. In some cases, community cooperation may be a sufficient basis for negotiating assignments of accountability. In other instances, incentives such as compliance with funding requirements or response to market pressures may make entities in the community willing to be held accountable. In some situations, however, accountability may result from regulatory or other legal requirements. Any combination of these factors may operate as a community resolves issues of accountability. For health departments, in particular, accountability under the "assurance" function (IOM, 1988) might be

viewed as encompassing facilitation of the overall intervention strategy in addition to responsibilities for specific services or activities.

Develop a Set of Performance Indicators

Accountability is operationalized in a CHIP through the adoption of concrete, specific, and quantitative performance indicators linked to accountable entities in the community that can contribute to health improvement. In contrast to a community health profile, which provides an overview of health status and community characteristics, performance indicators focus on a specific health issue and the activities undertaken as part of a health improvement strategy.

Because health issues have many dimensions and can be addressed by various sectors in the community, sets of indicators will be needed to make a meaningful assessment of overall performance. A set should include enough indicators to cover critical features of a health improvement effort but should not be so extensive that the details overwhelm the broader picture. As "indicators," these measures should be more than one dimensional, representing performance in important related areas (Sofaer, 1995).

Selecting indicators requires careful consideration of how to gain insight into progress achieved in the health improvement process. A set of indicators should be a balanced mix of population-based measures of risk factors and health outcomes and of health systems-based measures of services performed. An indicator set should include measures for the various accountable entities in the community, including those whose primary mission is not health specific. A balance is also necessary among indicators that reflect short-term gains and those that measure more fundamental long-term changes in community health.

Communities may also want to consider indicators of cooperation among organizations. The success of multiple organizations serving a particular community may depend on how well their services are coordinated. For example, senior citizens may be served by separate programs providing meals, transportation, outreach, and mental health services. Each program may be meeting its own goals, but if they are not working together, their overall impact may be diminished.

Communities will need criteria to guide the selection of indicators. In the committee's view, such criteria should include consis-

tency with a conceptual framework such as the field model for understanding factors that contribute to the production of health, salience to community stakeholders, and support for the social change processes needed to achieve health improvements. Indicators should also be assessed against criteria of validity and reliability, evidence linking performance and health improvement, sensitivity to changes in community health status, and availability of timely data at a reasonable cost. It is also essential to develop an operational definition for each measure to determine what data are needed and how (or if) they can be obtained. A review of existing indicator sets may suggest measures that could be adopted for community use and may be a source of tested operational definitions.2

The development of indicator sets and the selection of indicators are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 5. Appendix A illustrates the application of the committee's proposals with prototypical sets of community-level performance indicators for several specific health issues.

Implement the Improvement Strategy

Implementation of health improvement strategies and interventions requires action by many segments of a community. The particular mix of activities and actors will depend on the health issue being addressed and on a community's organization and resources. In most instances, these activities will require participation by public- and private-sector entities and often by entities that may not traditionally be seen as part of the health system. Finding ways to pool and redirect resources so that they can be

used as efficiently and effectively as possible is likely to be considerable challenge. For example, official waivers may be needed to remove restrictions on the use of categorical state and federal funding.

The tools of continuous quality improvement may be useful to some accountable entities as they determine how to meet the performance expectations of the health improvement process (e.g., see Worrall and Chambers, 1989; Nolan and Knapp, 1996). The community as a whole must also be able to respond successfully to the change processes that are set in motion. Some of the challenges and keys for success in social change have been examined in Chapter 3.

Monitor Process and Outcomes of the Improvement Strategy

Once a health improvement program is under way, performance monitoring becomes an essential guide. Information provided by the selected performance indicators should be reviewed regularly and used to inform further action. In assessing progress, a community coalition or other designated agent should consider whether accountable entities are taking appropriate actions and whether appropriate strategies and interventions have been adopted. As current goals are achieved and new ones adopted, the analysis and implementation cycle described by the committee should lead to other activities and the adoption of new performance indicators. Over time, a community, through its health coalition and the broader aspects of a CHIP, should reexamine its priorities and determine whether other health issues can be added to the health improvement portfolio or can replace issues on which good progress has been made.

The monitoring process will require access to comparable data from multiple sources that can be combined to produce a community-wide information resource. Comparability is affected by factors such as consistency over time and among community stakeholders in data definitions and measurement techniques. Efforts are needed to improve both the comparability of data from separate sources and the techniques for pooling these data. Further discussion of technical concerns related to data and data collection appears in Chapter 5 and Appendix B.

As for the community health profile, it will be important to examine these quantitative indicators in conjunction with qualitative information that can contribute to a more complete picture of the community context. Valuable information about the imple-

mentation of a health improvement strategy and the interpretation of indicator data (e.g., what is and is not working, alternative approaches that could be considered) can be gained from sources such as focus groups, key informant interviews, and town meetings.

In regard to access to data, health departments and other public agencies are generally expected to support the collection, analysis, and publication of data (e.g., IOM, 1988; Roper et al., 1992; NACHO and CDC, 1994; Turnock et al., 1994), although new approaches and new skills may be needed for performance monitoring programs. Data collection and analysis are also well established in various parts of the private sector, but those data have not always been shared with the community on a routine basis.3

Because data on all accountable entities are essential for effective performance monitoring, the committee has recommended that states and the federal government (in their policy development and regulatory roles) facilitate access to relevant data held by the private sector. As noted above in the discussion of community profiles, the committee recommends requiring that health plans, indemnity insurers, and other private-sector entities report standard types of data. The principle of helping meet the community's information needs should extend to providing more specialized data in support of performance monitoring focused on a specific health issue.

LEARNING FROM AND ABOUT HEALTH IMPROVEMENT PROCESSES

The cooperative and collaborative arrangements that are essential features of the health improvement process outlined by the committee are based on shared responsibility and mutual accountability among peers within a community rather than hierar-

chical relationships inside or outside a community. They will depend on goodwill and respect for diverse participants in the process. Experience suggests that using performance monitoring as a form of inspection and a basis for punishing those who are not producing as expected is not an effective way to alter behavior to improve outcomes (Berwick, 1989; Osborne and Gaebler, 1992). The monitoring process can become distorted by efforts to demonstrate adequate performance and thus lose its value as a tool to identify opportunities for improvement. Furthermore, in a voluntary collaboration, some participants may choose to leave rather than to change.

Instead, a CHIP should use performance monitoring to encourage productive action and broad collaboration. Because the health improvement process outlined by the committee is new, participants should see themselves as part of ''learning organizations" (e.g., Senge, 1990a,b; Ulrich et al., 1993) that can examine their own experience and use that knowledge to improve their operations. Thus, CHIP activities should include periodic examination of past health improvement efforts in the community. Valuable insight can be gained from both successful and unsuccessful experiences. Efforts to improve the CHIP itself can serve as a model for the improvement process being applied to community health issues.

A learning approach should be applied not only to the process but also to the science base for health improvement activities. Communities should draw on sources such as program reports and evaluations for local activities and on findings in the published research and evaluation literature that can help them identify the most promising opportunities. Evaluations of several major community health intervention projects are producing findings on specific interventions to address health problems, on the community intervention process itself, and on the analytic techniques to apply to community studies.

For example, the NHLBI programs to reduce coronary heart disease can provide both practical guidance on a variety of community-based approaches and cautionary lessons about their limitations (e.g., Elder et al., 1993; Fortmann et al., 1995; Murray, 1995; Luepker et al., 1996). Although interventions were often successful in reducing disease risk at the individual level, they generally were not able to reach a sufficiently large proportion of the population to alter community-level health outcomes. In addition, the unanticipated strength of other influences that were reducing risks for heart disease largely overwhelmed the

community-level impact of the interventions. Among the contributions of the studies of the Kaiser Family Foundation's Community Health Promotion Grant Program are methodological developments such as approaches to examine the element of "community activation" in health promotion efforts (Wickizer et al., 1993) and determining that community-level indicators (e.g., grocery store shelf space, amount of nonsmoking seating in restaurants) can be effective and less costly alternatives to individual-level measures for monitoring the impact of interventions (e.g., Cheadle et al., 1992).

The recently established Task Force on Community Preventive Services, organized by the CDC, is expected to compile evidence on the effectiveness of many kinds of community interventions. CDC has also collaborated with the University of Kansas to develop a handbook for evaluating community efforts to control and prevent cardiovascular disease (Fawcett et al., 1995). The handbook, which outlines an evaluation process and proposes many indicators that might be used, is being tested in a community setting. Additional guidance can be expected to emerge from the work of the 25 community coalitions participating in the Community Care Network research and demonstration grant program (AHA, 1995). Evaluation of Healthy Cities/Healthy Communities activities is just beginning and will require establishing a basis for assessing health impact. The diversity of the participating communities and their approaches to health promotion in the absence of a formal theoretical framework will, however, pose a challenge (Hancock, 1993).

The health improvement process and performance monitoring components presented by the committee in this report must be examined systematically from a broader perspective. The committee's proposal should be seen as a part of an evolving body of knowledge and expertise, but both the CHIP and the performance monitoring indicators discussed in Chapter 5 need to be tested and improved over time. The committee recommends implementing and assessing the proposed CHIP in a variety of communities across the country. These communities should differ in terms of size, political structure, socioeconomic and racial composition, region of the country, and specific health issues addressed. There should also be differences in how the health improvement process is operationalized in terms of the composition of the community coalition, how health issues are identified, the way in which performance indicators are selected and monitored, and the role played by state and local health departments.

An assessment will require documenting that the many aspects of the process have been implemented and examining its impact on a community in terms of structure, process, and outcomes. Points to be examined will include the sustainability of the health improvement process overall, the participation of various stakeholders (do most continue to participate?), the ability to obtain and use data for community profiles and performance indicators, and the impact on targeted health issues. Evaluation of the CHIP and other research on community health improvement should include consideration of the effectiveness of various approaches to the selection, collection, and presentation of data. Also needed is an assessment of the full range of public and private costs of carrying out the CHIP and of ways to achieve efficiencies in these efforts. Any examination of the impact on health outcomes must take into account the time needed to achieve desired changes; assessments conducted too soon may produce misleading results. Methodological issues addressed in other evaluation activities (e.g., Koepsell et al., 1992; Green et al., 1995) should be considered in developing a framework for an assessment of the community health improvement process. In addition, experience gained in evaluating multisectorial community programs that target social issues other than health can also help inform these assessment efforts (Connell et al., 1995).

Lessons drawn from the experiences of nine communities participating in the Community-wide Health Improvement Learning Collaborative, which was organized to demonstrate the application of CQI methods to community health issues, illustrate the potential value of looking back over a community's own experience and of looking at the experiences of others (see Box 4-3). Lessons such as these can be used by a CHIP already in operation or by a community that is just starting the process.

ENHANCING THE CAPACITY FOR COMMUNITY HEALTH IMPROVEMENT

To undertake activities aimed at maintaining and enhancing health, communities need certain basic capacities and resources to anticipate, prevent, and respond to health risks and to promote those community assets and protective factors that maintain and enhance the health of individuals, families, and populations. Some of these capacities include the authority to act, sufficient funds, access to data or data collection systems, varied expertise (coalition building, program management, data collection and

|

BOX 4-3 LESSONS FROM THE COMMUNITY-WIDE HEALTH IMPROVEMENT COLLABORATIVE In 1993, the Institute for Health Improvement and GOAL/QPC organized projects in nine communities, generally under the leadership of a health care organization, to demonstrate the application of continuous quality improvement techniques to respond to community health issues. The issues addressed were postneonatal mortality in Anchorage, Alaska; teen violence in Baton Rouge, Louisiana; health of women of childbearing age in Camden, New Jersey; child abuse and neglect in Edmonton, Alberta; motor vehicle injuries to children and adolescents in Kingsport, Tennessee; falls among the elderly in London, Ontario; cardiovascular Health in Monroe, Louisiana; preventive cardiovascular care in Rochester, New York; and teen traffic injuries and deaths in Twin Falls, Idaho. The projects began with basic questions on what was to be accomplished, how to know that a change was an improvement, and what changes to make to achieve improvements. Once those questions had been answered, a second set of questions guided the planning process: how to choose a topic; how to set up a measurement system; and how to select interventions. A review of experiences in planning and implementing these projects suggests several opportunities to move the health improvement process ahead more quickly:

SOURCE: Knapp and Hotopp (1995); Nolan and Knapp (1996). |

analysis, and so on), and the support of an array of community stakeholders. This section reviews capacities needed at the community level for health improvement efforts and performance monitoring and ways that activities in a broader context can improve the resources available to communities.

Community Capacities

"Capacity" includes those processes, products, and abilities that enable the entities contributing to the production of community health to perform varied functions. For example, the public health system should be able to maintain the readiness to respond to emerging health problems while operating population-based prevention and health protection programs on a routine basis. Similarly, health plans need the ability to provide high-quality clinical services and to maintain reliable administrative systems that support efficient operation of the organization. The ability of an individual or organization to perform according to expectations depends on motivation, capability, and preparedness to create the necessary infrastructure to carry out critical processes and thus achieve desired outcomes.

For the public health system, both core functions (IOM, 1988; see Box 4-4) and essential services (Baker et al., 1994)4 have been specified. These functions and the activities required to carry them out point to needed capacities. One source, Blueprint for a Healthy Community: A Guide for Local Health Departments (NACHO and CDC, 1994), proposes the following set of capacities: health assessment, including data monitoring and analysis; policy development; administration; health promotion; health protection; quality assurance; training and education for competent staff; and

|

BOX 4-4 CORE FUNCTIONS OF PUBLIC HEALTH

SOURCE: IOM (1988); Washington State Department of Health (1994). |

community empowerment. Adequate funding is also cited as an essential resource.

Other entities in a community also have specific functions that guide their participation in health improvement. These functions have been articulated in varying ways. For example, accreditation standards for hospitals and health plans point to clinical, organizational, and administrative functions that are deemed important (e.g., see JCAHO, 1996a; NCQA, 1996b). The NCQA (1996b) standards, for example, address quality improvement, physician credentials, member's rights and responsibilities, preventive health services, utilization management, and medical records.

Looking to the future, the Pew Health Professions Commission (1995) has proposed a set of "competencies" that the health professions should develop and enhance over the next decade (e.g., care for the community's health, clinical competence, prevention and health promotion, appropriate use of technology).

It is also possible to consider the capacities of a community as a whole—what the National Civic League (1993a) has called the civic infrastructure. The specific elements identified are citizen participation, community leadership, government performance, volunteerism and philanthropy, intergroup relations, civic education, community information sharing, capacity for cooperation and consensus building, community vision and pride, and inter-community cooperation. Various resources related to each of these areas have been identified (National Civic League, 1993a).

Capacities for the Community Health Improvement Process

The collaborative health improvement process described by the committee requires capacity in at least three interacting contexts: the community as a whole, a community health coalition, and a variety of individual community stakeholders. For the community, critical capacities for initiating a CHIP include an interest in protecting and improving health and a willingness to participate in a collective process toward that end. This support for health improvement can derive from individuals, organizations, or both and might develop from perceptions of unmet needs or promising opportunities. Valuable health-enhancing activities can, of course, be undertaken without a CHIP and bring considerable benefit to the community. Such efforts, however, may not reflect broad community priorities and may end up duplicating work being done on other projects or by other entities in the community. Part of the challenge a community will face is organizing the CHIP so that it can successfully blend these capacities and resources.

Where a CHIP can be instituted, the community coalition, or other agents of the process, will require a varied set of capacities to carry out all phases of the process. The ability to organize and sustain a CHIP, including the performance monitoring elements, is key. For some tasks, such as data collection or service delivery, a coalition may want or have to rely on the resources of individual participants. These participants must be able to support the CHIP and carry out the activities that implement a coalition's health improvement strategy. (The relationships among a community, a CHIP, and CHIP participants are presented here in a generic form that does not reflect the complexity and diversity of specific community settings.)

By examining the steps in a CHIP, it is possible to identify several capacities that will have to be available to the overall process.

-

Leadership: As proposed by the committee, a CHIP rests heavily on the willing collaboration of many community stakeholders and less on obligations created by law and regulation. Thus, a source of leadership is critical to initiate and sustain the process, particularly in reaching agreement among stakeholders regarding areas of accountable performance. In many communities, the health department is likely to lead a CHIP, but effective leadership may also come from others, in either the public or the

-

private sector. Communities may be able to draw on a variety of resources in the public and private sectors to enhance leadership capacity (e.g., Chamber of Commerce programs, regional and state-based public health leadership programs; also see resources identified by the National Civic League [1994]).

-

Community empowerment: This capacity which complements leadership, is necessary to help bring a broad spectrum of the community into all phases of a CHIP. A broad characterization suggests that community empowerment promotes participation by individuals, organizations, and communities in a process that aims at achieving increased individual and community control, political efficacy, improved quality of community life, and social justice (Wallerstein, 1992). Based on the health department role described in Blueprint for a Healthy Community (NACHO and CDC, 1994), community empowerment encompasses the ability to establish and maintain a community (versus an "expert") perspective on health priorities and activities and to establish an environment in which many stakeholders can work together. The ability to facilitate priority setting might also be included here.

-

Authority to act: Even though much of a CHIP depends on cooperative efforts, the need remains for formal authority to carry out some essential activities. Certain forms of data collection, for example, must have official sanction and must meet requirements for adequate protection of privacy and confidentiality. The implementation of specific health improvement strategies might also depend on having formal authority to act in the community at large or within a specific setting (e.g., to enforce environmental regulations, change a workplace smoking policy, or co-locate an immunization clinic with a public assistance office).

-

Expertise and skills: A CHIP will require access to diverse expertise and skills through its own staff (if one is created) and through the individuals and organization from the community who participate in the process. Two specific areas are noted here:

-

Subject matter expertise: A CHIP is likely to benefit from access to advice from subject matter experts to identify factors contributing to health problems, develop health improvement strategies that reflect evidence for the effectiveness of specific interventions, select performance indicators, and assess performance results. Academic health centers, schools of public health, and similar scholarly institutions could be particularly valuable sources of such assistance.

-

-