4

The Growing American Indian Population, 1960–1990: Beyond Demography

Jeffrey S. Passel

Introduction

For decades through 1960, the American Indian1 population, as enumerated in U.S. censuses, grew little if at all. From a population of 248,000 in 1890, American Indians2 increased to 524,000 in 1960. While this does represent a doubling of the population, the average annual growth rate over the entire 70-year period was only 1.1 percent—a very low figure resulting from high fertility and very high mortality. Since 1960, the Native American3 population has exhibited explosive growth, increasing from 552,000 to 1,959,000, or 255 percent. The average annual growth rate of 4.3 percent, extending over a 30-year period, is demographically impossible without immigration. Previous research (Passel, 1976; Passel and Berman, 1986) has shown that this extraordinary growth was achieved through changing patterns of racial self-identification on the part of people with only partial or distant American Indian ancestry, coupled with relatively high fertility and improving mortality.

Data Collection Methods

Data on the American Indian population collected in the 1970, 1980, and 1990 censuses are based on self-identification. That is, persons answering the census choose their response to the race question. A person choosing the American Indian racial response did not have to provide any substantiation or documentation of this identification. There was no requirement that an "American Indian" be enrolled as a member of a recognized tribe or that any tribal group recognize the respondent as a member, and there was no "blood quantum" requirement. This method of identification differs from that of previous censuses, in which a person's racial identification tended to be assigned by an enumerator, usually based on observation, local knowledge, or custom. Thus before 1970, a person would be classified as American Indian if he or she ''looked" Indian, was recognized by the local community as American Indian, or lived in an American Indian area.

Collection of racial data based on self-identification aids overall census taking by permitting respondents to fill out their own census forms, thus reducing the need for expensive in-person interviews. At the same time, self-identification adds a temporal component to the data. The responses elicited from the same individual (or group of individuals) may change over time in response to social, political, or economic conditions or variations in question wording. New identities may emerge, or old ones may disappear. Even though the names of groups or categories often remain the same from census to census, each census actually represents a "snapshot" in time, capturing the content of the moment, especially when data are based on self-identification. Analysts and other data users must be aware of underlying response patterns to interpret changes correctly.

For the American Indian population, the changes in method of identification between the pre-1960 and post-1960 periods4 have been associated with substantial changes in the nature of the data. In addition, the American Indian population has undergone rapid demographic change, including sizeable population growth coupled with substantial geographic redistribution. Many of these decadal changes have already been documented—Passel (1976) for the 1960–1970 decade; Passel and Berman

(1986) and Snipp (1989) for 1970–1980; and Passel (1992), Eschbach (1993), and Harris (1994) for 1980–1990.

Overview of the Chapter

This chapter expands on previous work by using various demographic measures to illustrate the magnitude of changing self-identification among the American Indian population and draws some implications for data analysis. It provides some basic demographic background on the size, growth, and geographic structure of the American Indian population, while explaining some of the factors contributing to the extraordinary increase in this population. Specifically, the next section focuses on differentiating the growth nationally according to demographic versus nondemographic factors. For example, the 1990 census count of 1,959,000 American Indians exceeds by 10 percent or 189,000 the figure expected on the basis of the 1980 census and demographic components of change (i.e., births and deaths) during the 1980s. This relatively large "excess" count comes on top of a 26 percent "excess" in the 1980 census count (Passel and Berman, 1986). Put another way, of the 1.4 million growth in the American Indian population between 1960 and 1990, about 762,000 is attributable to natural increase (i.e., births minus deaths) and 645,000 to nondemographic factors.

The section that follows explores some of the sources of both the demographic and nondemographic dimensions of the increase in the 1980s and earlier. Specifically, we use data on self-reported ancestry to demonstrate how such large increases could have occurred and what potential there might be for further increases in the future. We then use various demographic measures to pinpoint changes in the age structure of the American Indian population. Census survival ratios for this population over the last three decades show clearly that large increases are occurring for all age groups above age 10, with very notable concentrations at ages 10-19 and above age 30. In spite of the basic demographic constraint that age cohorts should decrease in size over time as people die, the American Indian cohorts aged 10 to 59 in 1990 were all larger in 1990 than in 1980.

The next section uses additional demographic methods to demonstrate how the dramatic growth in the American Indian population is distributed unevenly across states. The analysis shows clearly that, with the exception of Oklahoma, most of the population increase attributable to changing self-identification has occurred in states that have not historically been major centers of the American Indian population. With minor exceptions, this pattern has persisted over the last three decades.

The paper closes with a discussion of the implications of response patterns for data analysis pertaining to American Indians.

National Demographic Factors

Population Size and Growth Rate

For three decades, from 1890 through 1920, the American Indian population hovered around 250,000, changing little from census to census (see Table 4-1). In 1930, the population jumped to roughly 330,000, where it remained for another two decades. Since 1950, the American Indian population has shown a steady upward trend, with huge numerical increases since 1970, culminating in a 1990 census count of 1,959,000.

Average annual growth rates track these trends. From the 1890–1900 decade through 1940–1950, only the decade of the 1920s (3.1 percent) showed average annual growth exceeding 1.1 percent. In fact, for the 1890s and 1910s, the growth rates were negative as the enumerated American Indian population decreased. In 1950, growth rates began to jump

TABLE 4-1 American Indian Population: 1890-1990 Censuses

|

|

|

Decadal Change |

|

|

Census Year |

Population |

Amount |

Average Annual Rate |

|

American Indian, Eskimo, Aleut (50 states and D.C.) |

|||

|

1990 |

1,959,200 |

538,800 |

3.27 |

|

1980 |

1,420,400 |

593,100 |

5.55 |

|

1970 |

827,300 |

275,600 |

4.13 |

|

1960

|

551,700 |

208,300 |

4.01a |

|

American Indian Only (48 states and D.C.)

|

|||

|

1960 |

508,700 |

165,300 |

4.01 |

|

1950 |

343,400 |

9,400 |

0.28 |

|

1940 |

334,000 |

1,600 |

0.05 |

|

1930 |

332,400 |

88,000 |

3.12 |

|

1920 |

244,400 |

-21,200 |

-0.83 |

|

1910 |

265,700 |

28,500 |

1.14 |

|

1900 |

237,200 |

-11,100 |

-0.45 |

|

1890 |

248,300 |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

NOTE: Populations rounded to hundreds. a Rate set equal to 48 state rate. n.a., not applicable. |

|||

substantially—to 4 percent for the 1950s and 1960s and reaching a measured annual rate of 5.6 percent in the 1970s, before dropping to 3.3 percent in the 1980s. Such rates are extremely high, and the 5.6 percent rate for the 1970s is demographically impossible without international migration—a situation that characterizes the American Indian population, as shown below.

Error of Closure

We can gain some insight into the nature of these recent increases in the American Indian population with some simple analytic tools of demography. For a population not experiencing immigration, demographic increases come only from births and decreases only from deaths. We can express this relationship with the demographic "balancing equation," which relates the size of the population at one point in time to its size in the past:

where P1 = the population at time 1 (e.g., 1990)

P0 = the population at time 0 (e.g., 1960)

B = births during the time interval (e.g., 1960–1990)

D = deaths during the time interval

e = error of closure.

The final term in the equation, e or error of closure, is the amount needed to make the equation balance. Error of closure is normally small and usually represents changes in census coverage, unmeasured demographic change (such as immigration), or shifts in the makeup of the population. As we will see, errors of closure since 1960 have been large for the American Indian population. They appear to have resulted from increases in the population caused by changes in self-identification, that is, individuals who previously did not choose to call themselves American Indian, but did so in more recent censuses.

Table 4-2 shows the growth of the American Indian population and errors of closure for the last four decades (1950–1960 through 1980–1990). For the 1950–1960 decade, the error of closure amounts to only 1,900, or 0.4 percent of the 1960 American Indian population. This error is negligible and can easily be attributed to inaccuracies in measuring any of the four components in the balancing equation. For the 1960–1970 decade, however, the error of closure is very large, amounting to 91,000, or 11 percent of the 1970 population. In earlier work, Passel (1976) proved that the

TABLE 4-2 Components of Change and Error of Closure for American Indians: 1950–1990 Censuses

|

|

|

Intercensal Period |

|||

|

Component or Population |

30-Year Period 1960-1990 |

1980-1990 |

1970-1980 |

1960-1970 |

1950-1960a |

|

Final census |

1,959,200 |

1,959,200 |

1,420,400 |

827,300 |

508,700 |

|

Error of closure |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Amount |

645,400 |

188,700 |

365,500 |

91,200 |

1,900 |

|

Percentb |

32.9 |

9.6 |

25.7 |

11.0 |

0.4 |

|

Estimated population at final census |

1,313,900 |

1,770,600 |

1,054,900 |

736,100 |

506,900 |

|

Component for period |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Natural increase |

762,200 |

350,200 |

227,600 |

184,400 |

163,500 |

|

Births |

948,700 |

422,200 |

290,700 |

235,800 |

207,000 |

|

Deaths |

186,500 |

72,100 |

63,100 |

51,300 |

43,500 |

|

Initial census |

551,700 |

1,420,400 |

827,300 |

551,700 |

343,400 |

|

Average annual rate of natural increasec |

27.2 |

21.9 |

24.2 |

28.6 |

38.5 |

|

Births |

33.9 |

26.5 |

30.9 |

36.6 |

48.7 |

|

Deaths |

6.7 |

4.5 |

6.7 |

8.0 |

10.2 |

|

a American Indian only. b Base of percent is final census. c Per 1,000 mid-period population, as estimated. |

|||||

error of closure could not be attributed to errors in measuring the population (i.e., changes in census coverage), immigration, births, or deaths, but could be explained only by the creation of "new Indians," that is, individuals who had not previously identified as American Indian but chose to do so in the 1970 census.

For the 1980 census, the error of closure was unprecedented, amounting to 366,000, or 26 percent of the 1980 census count. This increase, too, can be attributed only to changing self-identification (Passel and Berman, 1986). The 1970–1980 increase is particularly noteworthy in that it occurred after the large 1960–1970 increase. Thus, not only did new individuals choose to identify as American Indian, but the previous shifts were maintained.

With the 1990 census, not only were these historical shifts further consolidated, but the trend toward shifting identity continued. The 1990 census count of 1,959,000 resulted in an error of closure for the decade of the 1980s of 189,000, or almost 10 percent. Given that the 1980s were marked by unprecedented levels of immigration (Fix and Passel, 1994), some of the error of coverage in 1990 has been attributed to the immigration of American Indians from Canada, Latin America, or the Caribbean (e.g., Harris, 1994). However, the foreign-born American Indian population increased only slightly between the 1980 and 1990 censuses—from 41,700 to 48,700,—while the percentage foreign-born decreased—from 2.7 to 2.4 percent. Although the error of closure is not as large, numerically or in percentage terms, as those of the previous decades, the continued, considerable shift in identity in 1990 again shows the enduring nature of the change.

Combining the data for the 1960–1990 period shows the magnitude of the shifts that have occurred. Between 1960 and 1990, the American Indian population increased by 1,407,000, from 552,000 to 1,959,000. During these three decades, the measured natural increase of the American Indian population (i.e., the excess of births over deaths) amounted to 762,000 (see Table 4-2). This leaves almost 645,000 persons, or 33 percent of the 1990 census count of American Indians, that cannot be accounted for by demographic factors, but must be explained by the changing nature of American Indian self-identification during the 30 years.

Sources Of Nondemographic Increase

The 1980 and 1990 censuses provide some data that point to the source of the shifts in American Indian self-identification. In addition, some simple demographic measures can be used to demonstrate which age groups have been driving these changes.

Ancestry and Race

The data discussed above are from decennial census questions defining the "race" of the population; more specifically, the data for 1980 and 1990 represent individuals choosing American Indian in response to the census question on racial identification. This question required respondents to pick among specified categories and allowed only one response in both the 1980 and 1990 censuses. However, both censuses also asked a broader question on "ancestry." The 1990 census question—worded "What is this person's ancestry or ethnic origin?"—required respondents to write in their own response and permitted more than one ethnic identification. These "ancestry" data are thought to elicit a broader ethnic identification, including some with lesser degrees of attachment than the racial classification (Waters, 1990).

The ancestry data show a very large population that claims some degree of Indian ancestry—a much larger population than that choosing to identify with the American Indian in racial terms. In 1980, 6.8 million persons claimed American Indian ancestry, of which only 21 percent, or 1.4 million persons, chose to identify with the American Indian racial group (Table 4-3). Likewise, in 1990, only 22 percent of the 8.8 million people claiming American Indian ancestry identified as American Indian by race. Thus, there is very large pool of "potential" American Indians, i.e., persons with some American Indian ancestry who may or may not choose to identify as American Indian by race. In this context, the errors of closure in 1980 and 1990 represent very small fractions of the "potential" American Indian population—5 percent in 1980 and only 2 percent in 1990. Thus, the possibility exists for further large increases in the American Indian population in the future, if social, political, economic,

TABLE 4-3 American Indian Population by Race and Ancestry: 1990 and 1980 Censuses

|

|

1990 Census |

|

1980 Census |

|

|

American Indian Definition |

Amount |

Percent |

Amount |

Percent |

|

By ancestry, total |

8,798,000 |

100 |

6,766,000 |

100 |

|

By race |

|

|

|

|

|

Census count |

1,959,000 |

22 |

1,420,000 |

21 |

|

Estimate from previous census |

1,771,000 |

20 |

1,055,000 |

16 |

|

Error of closure |

189,000 |

2 |

366,000 |

5 |

|

By ancestry, but not by race |

6,839,000 |

78 |

5,346,000 |

79 |

and methodological factors continue to encourage the shifts in identification.

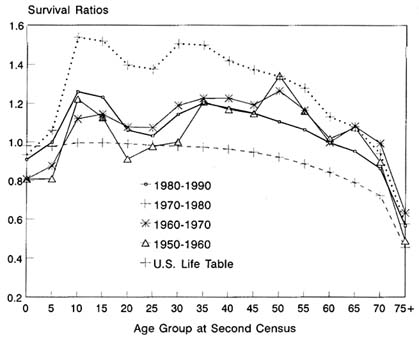

Age Patterns of Increase

Another demographic measure, the census survival ratio (CSR), offers a tool for ascertaining whether the large increases in the American Indian population over the last four decades are concentrated in specific age groups or cohorts. The CSR is a simple measure: it is the ratio of the population in a given age cohort in one census to the same group of people in the previous census, i.e., the age group 10 years younger in the census 10 years earlier:

where CSRx,t = census survival ratio for age × at time t (e.g., ages 10–14 in 1990)

Px,t = population aged × at time t (e.g., aged 10–14 in 1990)

Px - 10,t - 10 = population age × - 10 at time t - 10 (e.g., aged 0–4 in 1980).

Since the American Indian population experiences negligible immigration, the CSRs should all be less than 1.0 because the population in an age cohort can only decrease through mortality. If CSRs are greater than 1.0, they indicate movement into a cohort, in the case of American Indians through shifts in self-identification. The greater the CSR, the larger the shift into the population.

For the 1980 and 1990 censuses, the American Indian CSRs show a very strong age pattern of increases. For ages 10–19, the CSRs exceed 1.2, indicating increases of more than 20 percent in these cohorts as they aged from 0–9 in 1980 to 10–19 in 1990. In addition, all cohorts aged 30–59 have large CSRs, indicating sizeable increases at these ages. Thus, the figures for ages under 10 and 20–29 are consistent with data from the previous 10-year period, but other cohorts show increases that can be attributable only to "new" individuals identifying as American Indian. A virtually identical pattern shows up for the 1950–1960 and 1960–1970 decades (Figure 4-1). For 1970–1980, all of the CSRs are much higher than in other decades because the overall error of closure was much greater. For ages 10–49 in 1980, the CSRs exceed 1.40, indicating at least 40 percent increases in size beyond demographic changes.

Accompanying the large CSRs are, of course, numerical increases in cohort size that have occurred for all ages 10–59 in every census since 1960, with the exception of ages 20–34 in 1950. Particularly large increases

FIGURE 4-1 Census survival ratios for American Indians, 1950–1990.

occurred in the last two censuses for cohorts aged 10–49. Some actual numbers illustrate the striking character of these changes. For American Indians born in the 1940s, about 96,000 were enumerated in their first census, in 1950. By the time this group had reached their 40s in the 1990 census, they had more than doubled to 223,000. Those born in the 1950s showed an even greater increase in size, from 175,000 in 1960 (at ages 0–9) to 321,000 in 1990 (at ages 30–39). All birth cohorts of American Indians reaching adulthood in the post-World War II era have participated in the accretions from changing self-identification.

Birth Statistics

The exceptions to census survival ratios greater than 1.0 are the cohorts born in the decade before the census, i.e., at ages 0–9. Low CSRs are to be expected at these ages because young children are omitted from censuses at high rates, particularly in populations such as American Indians with large households, high poverty rates, and many difficult-to-enumerate situations (Robinson et al., 1992). Even for the 1970–1980 decade,

with its huge increases in self-identification, the CSRs for ages under 10 approximate the combined effects of undercoverage and mortality, implying that the shifts in identification may not occur for young children. However, for American Indians, another definitional complication arises in these early age groups.

In computing CSRs for ages under 10, births in the decade preceding the census are compared with the census counts for ages 0–9. The birth statistics are not collected in the census, but are compiled from registration data by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The system used by NCHS to assign births to racial groups differs considerably from that used in collecting census data. For every birth, NCHS collects information on the race of the mother and the race of the father, based on self-identification.5 Until 1989, births were assigned to race groups by a rule that tended to favor assignment to racial minorities. Specifically, if only one parent was white, the child was assigned the race of the nonwhite parent; otherwise, the child was assigned the race of the father (if known). Beginning in 1989, NCHS dropped its "old rule" for official classification of births by race in favor of tabulations based only on the race of the mother or the race of the father.

As Table 4-4 shows, the "old" NCHS classification scheme produced numbers of American Indian births that are 20 percent or so higher than those produced by either the "father" or "mother" classification. However, none of the three classification methods is consistent with the way children were identified in the censuses of 1980 and 1990. In their first census, the total number of young American Indian children (under age 10) was roughly comparable to the most inclusive classification method, i.e., the "old" NCHS rule. However, by the time the 1970s birth cohorts had reached their teens in 1990, even this rough comparability had disappeared as the 1990 census counts greatly exceeded the numbers of births. Thus, registration data on births of American Indians from NCHS cannot be considered comparable with decennial census figures and must clearly be used with caution. Further analyses presented below extend these cautions.

Geographic Distribution

The American Indian population is not uniformly distributed across the country; growth also has occurred differentially across states. American Indians are concentrated in the western region, which had 934,000 American Indians in 1990 (Table 4-5), or 48 percent of the U.S. total. The

TABLE 4-4 American Indian Births Based on Alternative Classification Procedures: 1968–1989

south had the next largest number with 563,000, or 29 percent. Just a handful of states have large American Indian populations. Only four had more than 100,000 in 1990: Oklahoma (252,000), California (242,000), Arizona (204,000), and New Mexico (134,355). There were another nine states with 45,000–100,000 American Indians: Alaska (86,000), Washington 81,000), North Carolina (80,000), Texas (66,000), New York (63,000), Michigan (56,000), South Dakota (51,000), Minnesota (50,000), and Montana (48,000). These top 13 states had 72 percent of the 1990 total U.S. population of American Indians.

The 1,959,000 American Indians represent only 0.8 percent of the 1990 total U.S. population. In every state, the American Indian population constituted only a small minority of the population, with Alaska having the largest percentage at 15.6 percent. In only 7 other states did American Indians represent as much as 2 percent of the total population: New Mexico (8.9 percent), Oklahoma (8.0), South Dakota (7.3), Montana (6.0), Arizona (5.6), North Dakota (4.1), and Wyoming (2.1).

Errors of Closure for States

The geographic concentration of American Indians has actually decreased substantially over the last 40 years. In the 1950 census, 19 states plus Alaska had 3,000 or more American Indians and accounted for 93 percent of the total U.S. American Indian population. These states have represented a steadily decreasing percentage of the American Indian population since then: 90 percent in 1960, 84 in 1970, 81 in 1980, and only 78 percent in 1990. This deconcentration has occurred in part because of migration from the original 19 states to the other 31 (Eschbach, 1993). However, most of the deconcentration is actually attributable to changes in self-identification because increased reporting as American Indian, as measured by error of closure, has occurred disproportionately in the states that did not have large American Indian populations in 1950.

We first divide the states into two groups: 19 states that historically have had large American Indian populations, i.e., more than 3,000 American Indians in 1950, and are designated ''Historical Indian" states6 or simply "Indian states;" and the remaining 31 states plus the District of Columbia, which historically have not had large American Indian populations

TABLE 4-5 American Indian Population and Components of Change, for Regions, Divisions, and States: 1980–1990

|

|

Census Counts |

|

|

Average Annual Ratea |

Estimated 1990 Population |

Error of Closure (Implied Migration) |

|||

|

Region, Division and State |

1990 |

1980 |

Births 1980–1990 |

Deaths 1980–1990 |

Birth |

Death |

|

Amount |

Percentb |

|

U.S., Total |

1,959,200 |

1,420,400 |

422,200 |

72,100 |

25.0 |

4.3 |

1,770,600 |

188,700 |

9.6 |

|

Indian States* |

1,287,500 |

951,100 |

317,600 |

60,000 |

28.4 |

5.4 |

1,208,700 |

78,700 |

6.1 |

|

Non-Indian States |

671,800 |

469,300 |

104,600 |

12,100 |

18.3 |

2.1 |

561,800 |

110,000 |

16.4 |

|

Northeast |

125,100 |

79,000 |

15,600 |

2,900 |

15.2 |

2.9 |

91,700 |

33,500 |

26.8 |

|

Midwest |

337,900 |

248,400 |

75,400 |

13,800 |

25.7 |

4.7 |

310,000 |

27,900 |

8.3 |

|

South |

562,700 |

372,200 |

90,100 |

16,300 |

19.3 |

3.5 |

446,000 |

116,700 |

20.7 |

|

West |

933,500 |

720,700 |

241,200 |

39,000 |

29.2 |

4.7 |

922,900 |

10,600 |

1.1 |

|

New England |

32,800 |

21,600 |

5,000 |

800 |

18.2 |

3.0 |

25,700 |

7,100 |

21.5 |

|

Maine |

6,000 |

4,100 |

1,200 |

200 |

23.8 |

4.3 |

5,100 |

900 |

15.4 |

|

New Hampshire |

2,100 |

1,400 |

200 |

0 |

11.8 |

1.3 |

1,500 |

600 |

28.1 |

|

Vermont |

1,700 |

1,000 |

100 |

0 |

7.0 |

0.5 |

1,100 |

600 |

36.9 |

|

Massachusetts |

12,200 |

7,700 |

1,900 |

200 |

19.4 |

2.3 |

9,500 |

2,800 |

22.7 |

|

Rhode Island |

4,100 |

2,900 |

800 |

200 |

24.2 |

6.1 |

3,500 |

500 |

13.3 |

|

Connecticut |

6,700 |

4,500 |

700 |

100 |

12.1 |

2.4 |

5,100 |

1,600 |

23.7 |

|

Middle Atlantic |

92,400 |

57,400 |

10,600 |

2,100 |

14.2 |

2.8 |

65,900 |

26,400 |

28.6 |

|

New York* |

62,700 |

39,600 |

7,000 |

1,600 |

13.7 |

3.1 |

45,000 |

17,600 |

28.1 |

|

New Jersey |

15,000 |

8,400 |

2,100 |

300 |

17.8 |

2.9 |

10,100 |

4,800 |

32.2 |

|

Pennsylvania |

14,700 |

9,500 |

1,500 |

200 |

12.4 |

1.7 |

10,800 |

4,000 |

27.0 |

|

East North Central |

149,900 |

105,900 |

24,100 |

4,300 |

18.8 |

3.4 |

125,700 |

24,300 |

16.2 |

|

Ohio |

20,400 |

12,200 |

3,100 |

400 |

18.9 |

2.5 |

14,900 |

5,500 |

26.8 |

|

Indiana |

12,700 |

7,800 |

1,100 |

100 |

10.8 |

0.6 |

8,900 |

3,800 |

30.2 |

|

Illinois |

21,800 |

16,300 |

3,300 |

500 |

17.1 |

2.7 |

19,000 |

2,800 |

12.9 |

|

Michigan* |

55,600 |

40,100 |

7,500 |

1,400 |

15.7 |

2.9 |

46,200 |

9,500 |

17.0 |

|

Wisconsin* |

39,400 |

29,500 |

9,200 |

2,000 |

26.6 |

5.7 |

36,700 |

2,700 |

6.9 |

|

West North Central |

188,000 |

142,500 |

51,300 |

9,500 |

31.1 |

5.7 |

184,400 |

3,600 |

1.9 |

|

Minnesota* |

49,900 |

35,000 |

14,100 |

2,100 |

33.1 |

5.0 |

47,000 |

2,900 |

5.9 |

|

Iowa |

7,300 |

5,500 |

1,600 |

200 |

25.6 |

3.9 |

6,800 |

500 |

6.8 |

|

Missouri |

19,800 |

12,300 |

1,900 |

200 |

11.9 |

1.3 |

14,000 |

5,800 |

29.2 |

|

North Dakota* |

25,900 |

20,200 |

8,500 |

1,600 |

36.8 |

6.7 |

27,100 |

-1,200 |

-4.5 |

|

South Dakota* |

50,600 |

45,000 |

17,800 |

4,100 |

37.2 |

8.5 |

58,700 |

-8,100 |

-16.0 |

|

Nebraska* |

12,400 |

9,200 |

3,600 |

800 |

33.6 |

7.1 |

12,100 |

300 |

2.8 |

|

Kansas |

22,000 |

15,400 |

3,800 |

500 |

20.4 |

2.7 |

18,700 |

3,300 |

15.0 |

|

|

Census Counts |

|

|

Average Annual Ratea |

Estimated 1990 Population |

Error of Closure (Implied Migration) |

|||

|

Region, Division and State |

1990 |

1980 |

Births 1980–1990 |

Deaths 1980–1990 |

Birth |

Death |

|

Amount |

Percentb |

|

South Atlantic |

172,300 |

118,700 |

23,700 |

4,900 |

16.3 |

3.3 |

137,600 |

34,700 |

20.1 |

|

Delaware |

2,000 |

1,300 |

200 |

100 |

11.3 |

4.5 |

1,400 |

600 |

28.6 |

|

Maryland |

13,000 |

8,000 |

1,500 |

100 |

14.7 |

1.2 |

9,400 |

3,500 |

27.2 |

|

District of Columbia |

1,500 |

1,000 |

100 |

0 |

5.2 |

2.6 |

1,100 |

400 |

27.5 |

|

Virginia |

15,300 |

9,500 |

1,300 |

200 |

10.5 |

1.5 |

10,600 |

4,700 |

30.8 |

|

West Virginia |

2,500 |

1,600 |

100 |

0 |

4.9 |

0.6 |

1,700 |

800 |

31.0 |

|

North Carolina* |

80,200 |

64,700 |

16,000 |

3,900 |

22.1 |

5.3 |

76,800 |

3,400 |

4.2 |

|

South Carolina |

8,200 |

5,800 |

800 |

100 |

12.1 |

1.3 |

6,500 |

1,700 |

21.0 |

|

Georgia |

13,300 |

7,600 |

900 |

100 |

9.0 |

0.8 |

8,500 |

4,900 |

36.5 |

|

Florida |

36,300 |

19,300 |

2,800 |

400 |

10.0 |

1.5 |

21,600 |

14,700 |

40.5 |

|

East South Central |

40,800 |

22,500 |

3,500 |

700 |

11.0 |

2.1 |

25,300 |

15,500 |

38.0 |

|

Kentucky |

5,800 |

3,600 |

400 |

0 |

9.1 |

1.0 |

4,000 |

1,800 |

30.9 |

|

Tennessee |

10,000 |

5,100 |

600 |

100 |

8.5 |

0.8 |

5,700 |

4,400 |

43.4 |

|

Alabama |

16,500 |

7,600 |

600 |

100 |

4.8 |

0.7 |

8,100 |

8,400 |

51.1 |

|

Mississippi |

8,500 |

6,200 |

1,800 |

500 |

25.1 |

6.5 |

7,600 |

1,000 |

11.4 |

|

West South Central |

349,600 |

231,000 |

62,900 |

10,800 |

21.7 |

3.7 |

283,100 |

66,500 |

19.0 |

|

Arkansas |

12,800 |

9,400 |

1,500 |

100 |

13.9 |

1.3 |

10,800 |

1,900 |

15.2 |

|

Louisiana |

18,500 |

12,100 |

2,900 |

300 |

19.1 |

1.9 |

14,700 |

3,900 |

20.8 |

|

Oklahoma* |

252,400 |

169,500 |

52,600 |

9,900 |

24.9 |

4.7 |

212,200 |

40,200 |

15.9 |

|

Texas |

65,900 |

40,100 |

5,800 |

500 |

10.9 |

0.9 |

45,400 |

20,500 |

31.1 |

|

Mountain |

480,500 |

364,400 |

135,200 |

23,600 |

32.0 |

5.6 |

476,000 |

4,500 |

0.9 |

|

Montana* |

47,700 |

37,300 |

15,000 |

3,100 |

35.3 |

7.2 |

49,200 |

-1,500 |

-3.1 |

|

Idaho* |

13,800 |

10,500 |

3,200 |

700 |

26.5 |

5.9 |

13,000 |

800 |

5.5 |

|

Wyoming* |

9,500 |

7,100 |

3,100 |

600 |

37.8 |

6.7 |

9,700 |

-200 |

-2.0 |

|

Colorado |

27,800 |

18,100 |

5,700 |

600 |

25.0 |

2.6 |

23,200 |

4,600 |

16.5 |

|

New Mexico* |

134,400 |

106,100 |

37,600 |

6,500 |

31.2 |

5.4 |

137,200 |

-2,800 |

-2.1 |

|

Arizona* |

203,500 |

152,700 |

58,600 |

10,300 |

32.9 |

5.8 |

201,100 |

2,500 |

1.2 |

|

Utah* |

24,300 |

19,300 |

6,900 |

800 |

31.8 |

3.9 |

25,300 |

-1,100 |

-4.3 |

|

Nevada* |

19,600 |

13,300 |

5,000 |

1,000 |

30.6 |

6.0 |

17,400 |

2,300 |

11.6 |

|

Pacific |

452,900 |

356,400 |

105,900 |

15,400 |

26.2 |

3.8 |

446,900 |

6,100 |

1.3 |

|

Washington* |

81,500 |

60,800 |

18,500 |

3,500 |

26.0 |

4.9 |

75,800 |

5,700 |

7.0 |

|

Oregon* |

38,500 |

27,300 |

7,100 |

1,200 |

21.6 |

3.7 |

33,200 |

5,300 |

13.8 |

|

California |

242,200 |

201,400 |

52,400 |

5,400 |

23.6 |

2.5 |

248,400 |

-6,200 |

-2.6 |

|

Alaska* |

85,700 |

64,100 |

26,300 |

5,100 |

35.1 |

6.8 |

85,300 |

400 |

0.4 |

|

Hawaii |

5,100 |

2,800 |

1,600 |

100 |

40.6 |

3.3 |

4,200 |

900 |

16.9 |

|

NOTE: All figures include Eskimos and Aleuts. Births projected for 1989–1990; deaths for 1988–1990. * Indian states include all states with 3,000+ Indians in the 1950 census, except California. a Rates per 1,000 mid-period population. b Base of percent is estimated 1990 population. |

|||||||||

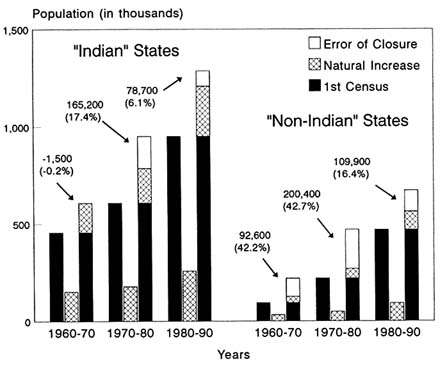

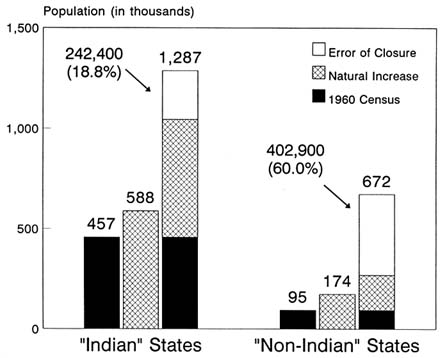

FIGURE 4-2 Error of closure by decade and state groups for American Indians, 1960–1990.

and are designated "non-Indian states." For each group of states, we can define error of closure as above. The measure is so large for many states that it must be interpreted as indicating changes in self-identification.

For the 1960–1970 decade, the "Indian" states had essentially no error of closure—actually a negative error of closure amounting to 1,500 persons, or 0.2 percent of the population (Figure 4-2). This magnitude indicates little change in reporting or possibly a small amount of out-migration from the "Indian" states. The remaining 32 "non-Indian" states, however, showed a growth exceeding natural increase (i.e., error of closure) of 93,000, or 42 percent of the 1970 population of these states. Thus, the large increase from changing self-identification in 1970 was completely confined to the states that historically had not had significant American Indian populations.

Similar patterns occurred in the next two decades, although not to the extreme shown in the 1960–1970 decade. For 1970–1980, the "Indian"

FIGURE 4-3 Error of closure by state groups for American Indians, 1960–1990.

states had an error of closure of 165,000 or 17 percent, whereas in the "non-Indian" states it amounted to 200,000, or fully 43 percent of the 1980 population in these states. The errors were more muted for 1980–1990:79,000 or 6 percent in the "Indian" states and 110,000 or 16 percent in the "non-Indian" states. (See Table 4-5 for full detail on the 1980–1990 errors of closure.) Thus, the percentage errors for each decade are all smaller in the "Indian" states than for every decade in the ''non-Indian" states. For the entire 30-year period, the error of closure in the "Indian" states is 242,000 or 19 percent of the 1990 population, whereas it is 403,000 or 60 percent in the "non-Indian" states (Figure 4-3). These patterns imply that shifts in identification are more likely to occur in areas without large concentrations of American Indians or significant reservation populations. In the "Indian" areas, which have reservations and large concentrations, identification as American Indian is more established by both self and community and so is less likely to change over time.

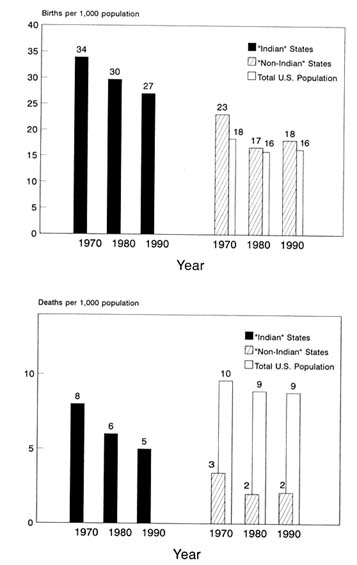

Births and Deaths

Crude birth and death rates demonstrate further the incompatibility of census and vital statistics data on American Indians. Direct observation of substantial inconsistencies in race reporting on matched birth and infant death certificates has been reported (Hahn et al., 1992). The crude rates also show inconsistencies and changes in racial identification of American Indians over time. Crude birth (and death) rates are measured as births (deaths) divided by population. The birth (death) data are collected by NCHS using its own data collection method and classification for racial identification. To the extent that changes in self-identification are captured in the census and not in vital statistics, birth and death rates will be excessively low in areas where there is a great deal of over reporting as American Indian in the census. In other words, the census figures will be inflated relative to the vital statistics in those areas.

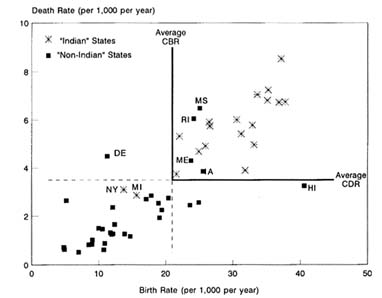

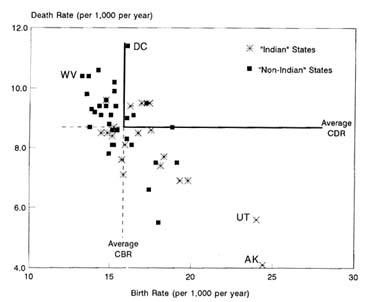

Figure 4-4 shows the differences in crude birth and death rates between "Indian" and "non-Indian" states for 1970, 1980, and 1990. Birth rates in "Indian" states are substantially higher than in the remaining ''non-Indian" states, which have American Indian birth rates approximating (but slightly higher than) the rates for the total population. This pattern does not, by itself, prove that there are data inconsistencies. Birth rates in the "non-Indian" states may simply be lower than the rates in the "Indian" states. However, taken together with the patterns of crude death rates, the birth rates do support the data inconsistency hypothesis.

The patterns of crude death rates are much more extreme and striking than those of the birth rates. In fact, the death rates are not consistent with simple demographic differences across the states. The death rates in "Indian" states are higher—a great deal higher—than those for American Indians in the "non-Indian" states. In fact, the death rates in "non-Indian" states are so low that they suggest serious under identification in the vital statistics (numerator) or over reporting as American Indian in the census data (denominator). The patterns across time and across the groups of states provide another strong indication of increasing identification as American Indian in the "non-Indian" states, as well as substantial differences in identification between the census and vital statistics systems.

The strong influence of the denominator (i.e., the census count) in the vital rates can be demonstrated in another way. In the United States, high crude birth rates in states are normally associated with low crude death rates and vice versa, because of age-structure effects. In other words, the high crude birth rates usually lead to a relatively young population with large concentrations of children and adults of child-bearing age, i.e., low-death-rate age groups. Such age structures tend to have low

FIGURE 4-4 Crude birth and death rates by state groups for American Indians, 1970–1990.

crude death rates. Conversely, states with high crude death rates tend to have high percentages of elderly persons and thus low crude birth rates. Utah (crude birth rate of 24.0 per thousand total population and crude death rate of 5.6 in the 1980s) and Florida (crude birth rate of 14.2 and crude death rate of 10.6) provide extreme examples of this negative relationship.

Overall, the negative relationship between crude birth rates and crude death rates for the total population at the state level is very strong, with a correlation coefficient of -0.73 for the 1980s.

The American Indian population by state, however, shows just the opposite—a strong direct relationship between American Indian birth and death rates in the 1980s (shown in Table 4-5). The correlation coefficient between the two is extraordinarily high at +0.85. The "Indian" states have high American Indian birth and death rates, whereas the other states are low on both. (See Figure 4-5 and 4-6 for the strongly contrasting patterns in the relationship between crude birth rates and crude death rates for the total population and American Indians.) This pattern, so contrary to demographic expectations, must be driven by the size of the denominator (i.e., the census count), rather than the age structure and demographic behavior of the population. The very large denominators in "non-Indian" states artificially lower the computed crude birth rates and crude death rates because of the fundamental inconsistency between census data and vital statistics.

Conclusion

In general, the 1990 census data on American Indians appear to capture the basic demographic features of this population, such as the age structure and size, but shifts in self-identification suggest some caution in analyses of this population. The 1990 census data are somewhat more consistent with vital statistics and the previous census than in other decades, but some inconsistencies still remain. Although there were some changes in self-identification as American Indian over the 1980–1990 decade, the shifts were smaller, both absolutely and proportionately, than in the previous two decades. Even with these smaller shifts, however, individuals identifying as American Indian were much more likely to be associated with organized American Indian groups (e.g., tribes, recognized bands, Alaska Native villages) in some areas (e.g., "Indian" states) than in others. Similarly, community recognition of individuals as American Indian was more likely to agree with the individual's response to the census in these same areas.

In sum, the different patterns of population growth and change in "Indian" and "non-Indian" states imply a need for some caution in interpreting census data, but do not rule out the utility of the data for assessing the social, demographic, and economic situation of the American Indian population. Recognized inconsistencies between 1990 census data on American Indians, on the one hand, and vital statistics or the previous census, on the other, point to the desirability of restricting some analyses to certain areas and groups or proceeding with care and conducting specific

analyses to address data compatibility issues. However, for the areas with the largest concentrations of American Indians, the data should be extremely useful for analyzing socioeconomic and demographic conditions of different American Indian populations and other racial groups.

References

Eschbach, K. 1993 Changing identification among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Demography 30(4, November):635–652.

Fix, M., and J.S. Passel 1994 Immigration and Immigrants: Setting the Record Straight. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute.

Hahn, R. A., J. Mulinare, and S. M. Teutsch 1992 Inconsistencies in coding of race and ethnicity between birth and death in U.S. infants . Journal of the American Medical Association 267:259–263.

Harris, D. 1994 The 1990 Census count of American Indians: What do the numbers really mean? Social Science Quarterly 75 (September):580–593.

Passel, J. S. 1976 Provisional evaluation of the 1970 Census count of American Indians. Demography 13:397–409.

Passel, J. S. 1992 The growing American Indian population, 1960–1990. Unpublished paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Statistical Association, Boston, MA, August.

Passel, J. S., and P. A. Berman 1986 Quality of 1980 Census data for American Indians. Social Biology 33:163–182.

Robinson, J. G., B. Ahmed, P. Das Gupta, and K. A. Woodrow 1992 Estimation of Coverage in the 1990 United States Census Based on Demographic Analysis. Unpublished paper of the Population Division, U.S. Bureau of the Census, Washington, D.C.

Snipp, C. M. 1989 American Indians: The First of This Land. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Waters, M. C. 1990 Ethnic Options. Berkeley: University of California Press.