5

Retirement Age and Retirement Income: The Role of the Firm

Donald O. Parsons

Understanding the retirement behavior of American workers and their income security in retirement requires knowledge of the motivations of employers as well as workers and the government.1 For example, the federal government has implemented a wide range of laws to permit or encourage later retirement in the private sector. Legal restrictions were imposed on maximum age-of-hire rules and on mandatory retirement before age 70 in the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 (ADEA); both practices have since been effectively abolished. Other legislation has outlawed pension plans that stop pension accrual at age 65 or deny older new hires the right to participate in company pensions. In a different direction, the 1983 Amendments to the Social Security Act set up a time schedule for the raising of normal retirement under Social Security to age 67. At the same time, however, private employers are increasingly including special early retirement incentives in pension benefit formulas (Mitchell, 1992). Whether this trend is a passive response by employers to greater demands by workers for early retirement or an active attempt by employers to reduce the number of older workers is not clear, although one must at least entertain the second possibility.2

Firms contribute in two important ways to the income security of older

The comments of participants at the panel conference on retirement modeling, especially those of Dallas Salisbury and Eugene Steuerle, are gratefully acknowledged. I have also benefited from the suggestions of Robert Clark and Richard Ippolito and from the detailed comments of members of the panel.

individuals: by providing jobs to those who want to work and by providing pension income to those who do not. The ability and willingness of private employers to offer jobs and pensions has been changing in the last two decades. Large changes have occurred, not only in age-based legislation, but in the economy's industrial base, the economic platform that provides both work opportunities and post-retirement income. Among other changes are the widely noted decline in the relative share of the large-firm, highly unionized sector and the expansion of the service sector.

This sectoral shift offers both opportunities and dangers to older individuals. On the one hand, employment in the service sector appears to be much more open to older Americans (Ruhm, 1990; Quinn, Burkhauser, and Myers, 1990), so that older individuals should have greater access to jobs in the future. On the other hand, they may need to work for more years if the expanding sectors remain relatively ungenerous in their pension offerings. Indeed recent evidence indicates that pension coverage in the United States declined in the 1980s, driven in part by relative employment declines in high-pension-coverage sectors (Woods, 1989; Parsons, 1991b, 1994; Bloom and Freeman, 1992; and Even and Macpherson, 1994a), although preliminary evidence from the May 1993 pension supplement indicates that coverage rates have stabilized in the 1990s (Woods, 1993; U.S. Department of Labor et al., 1994). At the same time, there has been a shift in the composition of pension coverage away from the traditional final-salary-based, retirement annuity programs (defined benefit plans) and toward savings-like, lump-sum programs (defined contribution plans) with payouts dependent on the returns-to-plan assets.3 These compositional shifts can also be partly explained by the relative decline in industries that traditionally offered defined benefit plans, although both the general decline in pensions and the shift toward defined contribution plans are evident within industrial sectors as well. The trend toward defined contribution plans introduces an unwelcome element of uncertainty into policy planning because we lack broad experience with such plans.

What are the strategies underlying employers' retirement and pension policies? How and, of equal importance, why do these strategies vary across firms, workers, and market structures?4 Although one can occasionally uncover direct evidence on employer intentions (Gratton, 1990), usually this information must be gleaned indirectly from observations of the age-related elements of employment conditions, including maximum age-of-hire restrictions, compulsory retirement rules, actuarially unfair pensions, age-restricted eligibility for retirement plans, and special retirement incentive programs or ''windows." The motivations for age-based policies are often ambiguous. With pensions, for example, the firm has two plausible objectives: (1) to serve as an efficient conduit for fringe benefits that its workers value, for example, as a mechanism for securing tax-deferred retirement income, and (2) to structure compensation in a way that induces desirable behavior from workers at least cost, shaping compensation

profiles and bonding worker mobility and on-the-job performance. Evidence for each of these two objectives, which are not mutually exclusive, can be found in the literature, but the quantitative importance of each in molding the firm's behavior toward the aged remains unknown.

Throughout this review, special attention is paid to the impact of firm size on retirement policies. To anticipate later conclusions, retirement age and pension coverage are strongly shaped by firm size and union status, and a substantial part of recent trends in pension coverage and type (defined benefit and defined contribution) can be explained by shifts in industrial structure away from the large-firm, unionized sector. The effects of firm size and union status on retirement age and retirement income can themselves be explained by transactions costs, especially firm size differences in (1) the administrative costs of sorting and reassigning older workers as their productive attributes evolve and (2) the administrative costs of providing retirement income to separated workers. Recent trends in pension structure can be explained by changes in these same administrative costs, especially those changes induced by shifting government regulations, although permissive legislation that has expanded the range of tax-favored pension vehicles to include 401(k) plans has also had a major impact on recent pension developments. Alternative hypotheses, notably broader transactions-cost hypotheses that stress agency problems and/or contract reliability, can explain many of the same behaviors, and more detailed data and more carefully developed implications are required to assess the relative importance of these competing, but not mutually exclusive, hypotheses.

This paper proceeds in the following way. I begin in the next section by summarizing the "aging problem" as the firm might view it and then review aspects of the firm's employment contracting behavior that are of special relevance to aging policies. The function of this section is to gather together in one place a set of worker and firm behavioral characteristics that can explain the retirement and pension policies of the firm and the variation in these policies across firm size. In the section on "The Employment of Older Workers," I begin the review of what is known about the role of the firm in retirement behavior and retirement income, turning first to the employment question: what determines the firm's propensity to employ older workers? I examine the mechanisms firms use to alter the extent of employment of older workers—the age profile of compensation, mandatory retirement, and maximum age-of-hire. In the section "Employer-Provided Pensions," I then consider the closely related question of firm pension policies, again focusing on why firms establish the plans that they do. The answers to this question are then used to explain recent pension trends, in aggregate and by type of pension plan. I then conclude in the final section with a discussion of the data collection and research needed to develop more reliable retirement-age and pension policy models.

THE AGING WORKER AND THE FIRM

The Aging Worker

The aging worker faces a variety of problems that potentially affect his or her productivity. (That these effects exist does not mean that firms correctly estimate their magnitudes; I return to the question of age bias below.) At the most basic level, mortality rates increase with age. This reality may limit the worker's usefulness to the firm, especially if substantial training is involved. Two additional dimensions of the aging process may be important: (1) that physical and mental attributes, especially physical attributes, decline on average with age and (2) that the decline is not uniform across individuals—some workers suffer declines and others do not.5

Self-reported health data from the National Center for Health Statistics illustrate the age profile of depreciation of the human "machinery" along several dimensions; see Table 5-1.6 As the table indicates, certain physical problems arise early. In the age interval 55 to 65, about 16 percent of both men and women report difficulty walking a quarter of a mile, while 5 percent of men and 8 percent of women report difficulty lifting a 10-pound weight. In the oldest category, those 85 years of age or more, 50 percent of men and 60 percent of women report difficulty walking a quarter mile. On average, mental skills decline later in life.

TABLE 5-1 Health Statistics for Persons Ages 55 and Over in the United States, 1984, in Percentages

|

Ages |

Annual Death Rate |

Have Difficulty |

|||

|

Walking 1/4 Mile |

Lifting 10 lbs. |

Managing Money |

|||

|

Males |

|

||||

|

55–64 |

1.7 |

15.5 |

5.2 |

1.0 |

|

|

65–74 |

3.8 |

21.9 |

6.6 |

2.8 |

|

|

75–84 |

8.4 |

29.1 |

9.9 |

5.4 |

|

|

85+ |

18.1 |

48.3 |

19.9 |

19.0 |

|

|

Females |

|

||||

|

55–64 |

0.9 |

16.3 |

8.8 |

1.0 |

|

|

65–74 |

2.1 |

24.5 |

12.6 |

1.8 |

|

|

75–84 |

5.2 |

39.4 |

23.7 |

6.8 |

|

|

85+ |

14.1 |

61.5 |

40.8 |

26.2 |

|

|

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics (1987): column 1, p. 7; column 2, p. 45; column 3, p. 46; column 4, p. 54. The activity data are based on the National Health Interview Survey 1984 Supplement on Aging. |

|||||

Self-reported difficulty managing money is almost nonexistent between 55 and 64.7 Even in the 75-to-84 age interval, only 5 percent of men report trouble "managing money," a proportion that increases to 19 percent by age 85 and over (for women the corresponding statistics are similar—7% and 26%, respectively). The data also make clear that the onset of self-reported impairments is not uniform across the population. Most older individuals do not have a problem with these basic physical and mental skills. Among the men 85 or older, 50 percent report that they do not have difficulty walking one-quarter mile, 80 percent that they do not have difficulty lifting a 10-pound weight or managing their money.

It is reasonable to assume that work productivity is related to the individual's physical abilities and to his or her mental ones, with the relative importance of each dependent on the worker's job, so that work productivity in the population declines with age. Less clear, and in many ways less relevant, is whether the attributes of older workers decline with age. See Levine (1988) and Hurd (1993) for sympathetic reviews of the age/productivity literature. One could imagine a work environment sufficiently rigid in requirements and pace that all who continue working are of the same productivity; the overall decline in capabilities with age would be reflected in a reduced work rate. Certainly employers act as if abilities decline with age; the internal assessments of line managers in the Pennsylvania Railway Company, when that company first adopted a modern retirement and pension system at the turn of the century, reveal this to be the case, Gratton (1990). In a broader sample much more recently, Medoff and Abraham (1981) find evidence that productivity (as reported by supervisors) declines among older workers while pay increases. Kotlikoff and Gokhale (1992) use a novel methodology on data from a single large firm's personnel records to estimate employer perceptions of the productivity profiles for male managers, male and female office workers, and male and female salespeople. The basic proposition is that the present value of productivity and compensation should be equal at the time of hire. From wage histories and exit probabilities for workers with different ages of hire, they can estimate age profiles of productivity. There is persuasive evidence of declining productivity with age and also of large wage/productivity gaps at older ages for all but male salespeople and, somewhat more ambiguously, female salespeople, both of whom work on commission. Recall, however, that these estimates are based on employer beliefs of worker productivity. For a skeptical summary of employer beliefs in this area, see Levine (1988, chap. 8).

A caveat is that employer perceptions may not reflect reality. It is unambiguous that individuals fall prey to various physical and mental impairments at an increasing rate with age and that employers design employment contracts to moderate the effect of the aging phenomenon on firm profitability. At a minimum, these firm policies are a form of statistical discrimination—workers are treated as a class, old—that legislators have in many cases chosen to prohibit.8 A deeper question is whether employers systematically overestimate the magnitude

of this decline (Levine, 1988). Hurd (1993) provides a review of early efforts to deal with this difficult measurement issue. I suspect that empirical validation will be difficult. In situations in which objective productivity measures are available to the researcher, they are also likely to be available to the employer, but the greatest potential for bias occurs in situations in which productivity measures are the most ambiguous. In the remainder of this review, I assume that employers are reacting to what they believe to be the life-cycle productivity trend.

Obviously aging is a problem for the worker as well as the firm; of special importance to the worker is insuring himself or herself against earnings losses following the onset of a disabling condition. Such protection can take one of two forms, disability insurance or "self-insurance," accumulating sufficient assets to provide adequate consumption for a terminal period of low or no earnings. Private disability insurance coverage is notoriously incomplete and Social Security disability benefits are subject to a stringent but error-prone disability screen, placing much of the burden of income maintenance in old age on retirement programs. Of course, not all workers are equally concerned about this danger, or indeed about the future at all. Of importance to the firm's incentive to provide a pension plan, workers with high rates of time preference will place little value on pension plans, especially when they are young. As a summary, I offer the following propositions about workers and aging:

-

Physical and mental attributes, especially physical attributes, decline on average with age, but the decline is not uniform across individuals—some workers suffer declines and others do not (W1).

-

Workers are underinsured, especially against the early onset of health conditions that reduce work productivity (W2).

-

Workers differ in the weights they place on the future; that is, they are heterogeneous in discount rates (W3).

One additional aspect of worker preferences deserves special mention because of its unusual importance in the design of retirement and retirement income plans: downward adjustments in pay and responsibility are, on average, resented by the worker, the more so the more direct and obvious the adjustment and the more individual-specific it is (W4).

The claim that workers resent negative job actions is consistent with empirical evidence in a wide set of situations, including employer design of wage and layoff policies (Bewley, 1993).9 For a more general statement of this proposition, see Kahneman, Knetsch, and Thaler (1986). Of special importance here, workers seem to more readily accept compensation cuts in the form of actuarially unfair adjustments in pension accrual than cuts in cash payments.

The Firm

Firm retirement policies and retirement income policies are largely a function of workplace characteristics, not individual ones (Slavick, 1966; Parsons, 1992). Although there is a major exception to this rule for part-time workers, age-based contract terms vary little within a given workplace for full-time workers.10 This workplace homogeneity is partly the result of government actions, such as nondiscrimination rules for qualified pension plans, but it is also the result of the firm's own decision calculus; when legal, one or two mandatory retirement rules have typically covered the whole workplace (Slavick, 1966).

The firm's relationship with its workers can be conceptualized as a "contact."11 At the extremes, the employment relationship may be a spot-market transaction, with the firm's purchasing services from the worker for a relatively brief, well-defined interval, or a long-term contract, explicit or implicit, with the firm and workers' agreeing to an exchange of resources and services over a much more extended period. The primary economic factors that determine the length of the "contract" governing the employment relationship are the same as those that foster any sort of long-run contract, a relationship-specific investment on one or both parts (Williamson, 1975). In the employment contract, hiring costs and job training are believed to be investments of this type.12 The high correlation of general and firm-specific training (Mincer, 1988) implies that, other things being equal, high-skilled workplaces will have more enduring relationships than will low-skilled ones; the returns to these investments accrue over time and a significant part may be lost if the employer/employee pair separate. In general, workers and firms find it advantageous to have long-term relationships. The worker is spared the costs and uncertainties of finding another job; the firm is able to train its workers, assess them over a longer period of time, and assign each one to an appropriate position. The volatility of demand or complementary factors may make such relationships infeasible, however, and the net returns to such relationships are likely to vary, so that some types of firms will find it optimal to have short-term relationships with their workers. To summarize: high hiring and training costs and stable demand and supply conditions foster long-term contracts (F1).

Beyond these real considerations, information processes are believed to play a major role in the determination of contract form. When compared with smaller firms, large firms appear to have two attributes important to these contracts:

-

The costs of routine transactions are less in large firms (F2).

-

The costs of individual, idiosyncratic decisions (in this case the assignment and monitoring of workers) are greater (F3).

Economies of scale are almost invariably large when the same activities are repeated. Setting up a payroll system or a pension plan requires a significant

fixed cost. As the scale of a single operation increases, however, important information is less and less likely to reach the appropriate decision maker, or to be fully comprehended if it does (Williamson, 1967). As a consequence, the idiosyncratic aspects of a particular circumstance are likely to be lost, and decisions are likely to depend more heavily on broad rules (Oi, 1983a, 1983b, 1991). In particular, large firms are likely to perform very poorly at assessing individual attributes and appropriately assigning individuals to tasks (Garen, 1985). As Oi (1983a:79) remarked about the product market, "Large firms specialize in the production of standardized goods, while small firms supply customized goods that are produced in small quantity." It is plausible that firm personnel policies follow a similar pattern.

One can find ample support for propositions F2 and F3 in the retirement and retirement income literature.

Scale Economies in Pension Administration

Proposition F2 finds strong support in the administration costs of employer-provided pensions.13 Pension provision ultimately involves resource collection, management, and disbursement. Each of these activities has significant fixed-cost components, so that considerable cost savings result if the worker can costlessly pool his or her pension efforts with others; for example, searching for a portfolio manager need be undertaken once, not once for each worker.

The administrative costs of a pension plan potentially include a variety of expenses incurred in the setup and maintenance of the plan and of individual accounts, including the collection of pension contributions, the tracking of workers until retirement, the financial handling of accumulated contributions, and the disbursement of funds at retirement. The cost functions of each of these various administrative activities—collection, portfolio management, disbursement, and others—may vary in form, but the total cost function seems well fitted by a log linear function (Caswell, 1976; Mitchell and Andrews, 1981).

Consider then the following model which captures the major elements of past studies:

(1)

where C denotes total administrative costs, P denotes number of plan participants, A denotes total plan assets, F denotes the number of firms participating in the plan, X is a vector of other plan characteristics, and ∈ is a random element, assumed to be iid normal (independently and identically distributed). This model asserts that plan costs are a function of the number of plan participants, the assets per participant, the number of participants per firm (a measure of internal coordination costs), and possibly other factors. The crucial scale parameter is β1, which indicates economies of scale in pension administration if less than one (β1 < 1).

Caswell (1976), using this model to estimate the administrative cost structure of multiemployer pension plans in the construction industry, found strong evidence of large-scale economies. Drawing his data from informational forms submitted on collectively bargained pension plans to the Department of Labor in 1970, Caswell reported pension administrative costs per participant of approximately 4 percent of total contributions. Holding firm size (P/F) constant, Caswell estimated that a doubling of pension plan size yielded about a 20 percent reduction in administrative costs: ![]() −1 = −0.202.

−1 = −0.202.

Mitchell and Andrews (1981) estimated a log linear cost model similar to that of Caswell on a broader sample of multiemployer pension plans. Their data was drawn from 5500 Forms filed in 1975 in accordance with the Employment Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) regulations. They considered only defined benefit trust plans, but did not limit their study to collectively bargained plans. In a multivariate analysis similar in form to Equation (1), they found evidence of scale economies in pension administration that were strikingly similar to Caswell's results for the construction industry. With assets per participant (A/P) held constant, a doubling of pension plan size yielded about a 20 percent reduction in administrative costs: ![]() −1 = −0.170.14

−1 = −0.170.14

Also using data from Form 5500 filings, Turner and Beller (1989:438) report pension administrative costs per participant by plan size for (multiemployer) benefit plans in 1985. Although the Turner-Beller tables provide no data on many of the controls in the Caswell and the Mitchell-Andrews studies, estimation of the log linear model for defined benefit plans yielded estimates of scale economies similar to the earlier studies:15

(2)

Evidence on administrative scale economies in single-employer plans is less abundant, because it is difficult to isolate pension administrative costs within the firm. An accounting cost study of single-employer plans by Hay/Huggins (1990) reveals, however, that scale economies in single employer plans are large as well. Hay/Huggins employs a task-pricing approach, estimating the cost of activities required to maintain a defined benefit pension plan for several different plan sizes. The study appears to emphasize accountancy costs—the purchase of actuarial services to design the plan, the accounting time required to prepare the annual report, and so forth. The cost estimates for the day-to-day functioning of management, record keeping, and disbursement are probably less reliable. The estimated economies of scale for ongoing administrative costs in a defined benefit plan is (absolutely) greater than in the statistical cost studies reported above: ![]() −1 = −0.324. Given the potential bias in the study toward accountancy costs with their large fixed-cost component, this figure does not appear inconsistent with the 20 percent estimates of the multiemployer plans.

−1 = −0.324. Given the potential bias in the study toward accountancy costs with their large fixed-cost component, this figure does not appear inconsistent with the 20 percent estimates of the multiemployer plans.

Given the magnitude of the scale economies in pension plan cost, a surpris

ing finding is that small pension plans exist; indeed they exist in great number. In 1985 there were 800,000 single-employer plans covering 65 million participants, and 3,000 multiemployer plans covering 9 million workers (Turner and Beller, 1989:350). Apparently cross-firm pooling is expensive. Caswell's analysis indicates that the number of employers in multiemployer plans affects internal plan costs, perhaps owing to higher negotiation, coordination, and collection costs. Caswell's estimate of the effect on log costs of the log of (active) plan participants per firm (P/F) or ![]() is −0.153, which implies that a doubling of the number of employers, holding constant the total participant size of the pension plan, increases total administrative costs by 15 percent.

is −0.153, which implies that a doubling of the number of employers, holding constant the total participant size of the pension plan, increases total administrative costs by 15 percent.

These costs no doubt rise with heterogeneity, and it is not surprising that many existing multiemployer plans are industry-specific. Indeed many are the result of collective bargaining with a single union, a situation that is likely to provide a variety of cost savings. Union effects on pension coverage are most substantial in workplaces that would otherwise not naturally support them, for example, small firm industries in which interfirm mobility is high (Slavick, 1966; Freeman, 1985). Skolnik (1976) concludes his historical review on a similar note; multiemployer pension plans supported by unions in small-firm industries were apparently a major factor in the expansion of pension coverage in the 1950s and 1960s.

Diseconomies of Scale in Idiosyncratic Decisions

The evidence that large firms use rules rather than discretion is pervasive. Although more elaborate models of mandatory retirement can be developed (see below), mandatory retirement can be viewed as no more than the wholesale substitution of rules for discretion in the separation decision. Consistent with diseconomies of scale in idiosyncratic decisions, mandatory retirement rules were almost universal in very large workplaces and much less common in small ones (Slavick, 1966; see also Parsons, 1983). Slavick undertook an ambitious mail survey of establishments to ascertain their pension and retirement policies in 1961. The sample was "a random sample, stratified by size, of all business and industrial units with 50 or more employees reporting to the Bureau of Old-Age and Survivors Insurance in March 1956" (Slavick, 1966:8). In the first wave of the survey, 466 usable returns were obtained. The relationships of retirement policy by company size is reported in Table 5-2. The strong effect of company size on retirement policy is clear; in firms of size 50 to 249, 63 percent of all plants responding reported flexible retirement plans; in firms of 10,000 or more, 10 percent reported flexible plans. Only a modest number of establishments, under 20 percent in all firm size categories, reported mixed plans such as a flexible one for some workers, a mandatory one for others.

Additional evidence that the pattern of mandatory retirement reflects the higher costs of sorting in large firms can be found in Table 5-3, in which differ-

TABLE 5-2 Distribution of Local Plants by Company Size and Compulsory Retirement Status, 1961, in Percentages (Parentheses show number of local plants)

|

|

Retirement Policy |

||||

|

Size of Company |

Flexible |

Mandatory Late |

Mandatory Normal |

Mixed |

Total |

|

50–249 |

63.3% |

6.7% |

30.0% |

— |

100.0% |

|

|

(19) |

(2) |

(9) |

|

(30) |

|

250–499 |

40.0 |

11.4 |

42.8 |

5.7 |

100.0 |

|

|

(14) |

(4) |

(15) |

(2) |

(35) |

|

500–999 |

33.3 |

13.3 |

36.7 |

16.7 |

100.0 |

|

|

(10) |

(4) |

(11) |

(5) |

(30) |

|

1000–9999 |

14.2 |

17.0 |

53.8 |

15.1 |

100.0 |

|

|

(15) |

(18) |

(57) |

(16) |

(106) |

|

10,000+ |

10.3 |

37.9 |

32.8 |

19.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

(6) |

(22) |

(19) |

(11) |

(58) |

|

SOURCE: Slavick (1966:77). Copyright © 1966 by Cornell University. Used by permission of the publisher, ILR Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press. |

|||||

TABLE 5-3 Distribution of Local Plants by Company Size and the "Percentage of Employees Reaching the Compulsory Retirement Age Who Were Excepted From Compulsory Retirement Policies," 1961 (Parentheses show number of local plants)

|

Size of Company |

Percent of Employees Excepted |

|||||

|

0% |

1%–9% |

10%–29% |

30%–49% |

50%+ |

Total |

|

|

50–249 |

— |

20.0% |

40.0% |

20.0% |

20.0% |

100.0% |

|

|

|

(1) |

(2) |

(1) |

(1) |

(5) |

|

250–449 |

36.4 |

— |

63.6 |

— |

— |

100.0 |

|

|

(4) |

|

(7) |

|

|

(11) |

|

500–999 |

44.4 |

— |

11.1 |

33.3 |

11.1 |

100.0 |

|

|

(4) |

|

(1) |

(3) |

(1) |

(9) |

|

(50–999) |

32.0 |

4.0 |

40.0 |

16.0 |

8.0 |

100.0 |

|

|

(8) |

(1) |

(10) |

(4) |

(2) |

(25) |

|

1000–9999 |

71.8 |

10.3 |

12.8 |

— |

5.1 |

100.0 |

|

|

(28) |

(4) |

(5) |

|

(2) |

(39) |

|

10,000+ |

80.0 |

20.0 |

— |

— |

— |

100.0 |

|

|

(12) |

(3) |

|

(15) |

||

|

SOURCE: Slavick (1966:114). Copyright © 1966 by Cornell University. Used by permission of the publisher, ILR Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press. |

||||||

ences are reported by firm size in the extent to which mandatory retirement rules were ''excepted." In the smallest firm category (50 to 249), all plants reported making some exceptions to the mandatory retirement age; in the largest, 80 percent report zero exceptions to the rule. Clearly, not only are large firms more likely to impose mandatory retirement rules; those that do are more likely to enforce them strictly.

An additional factor is important in forming long-term relationships, namely the reliability of the contracting partners. The following transactions costs regularity has emerged (from, e.g., Oi, 1983a): large firms are more reliable long-term contracting partners (F4). Reasons for this are not hard to enumerate. Reputational enforcement of implicit contracts is likely to be stronger in large firms (Parsons, 1986). A potential new hire is less likely to know of the reliability of a small firm than of a large one from casual hearsay. The new hire's odds of encountering a disaffected worker or a friend or relative of one from a small firm becomes vanishingly small in large labor markets. Small firms are also more likely to fail than are large ones and therefore they make less attractive contracting partners, even if much is known about their prior relationships with workers; a failed firm is a poor debtor.

Evidence for the greater contract reliability of large firms can be found in the pension literature. To the extent that employers are more reliable, they can offer a greater number of "insurance" features in the pensions they provide. Inflation protection would seem an important feature of a pension plan, one that would be valuable to most workers. A potentially valuable inflation insurance attribute of a pension is the inflation adjustment of retiree benefits after retirement. If not an explicit part of a collective bargaining agreement, such a process relies heavily on reputation mechanisms for enforcement. The presence of such post-retirement pension income protection is, therefore, an indicator of reliable implicit contracting between the organization and the worker.

Clark, Allen, and Sumner (1986) report on the post-retirement adjustment of pensions during the high (and unexpected) inflation period of the 1970s; between 1973 and 1979, the consumer price index increased by 63.3 percent. In the pension sample they analyzed, the change in benefits as a percentage of the change in the consumer price index over the 1973–1979 period among pre-1972 retirees was 37.9 percent (1986:185).16 The relative adjustment was 45.2 percent among union plans, only 29.2 percent among nonunion ones. Much of this difference, however, appears to be due to the disproportionate union representation in large firms. Consider the reported variation in post-retirement adjustments in benefits by collective bargaining status and plan size in Table 5-4. It would appear that post-retirement adjustments within pension plans of equal size are largely unaffected by collective bargaining status within plans of similar size.

Evidence from a wide variety of sources indicates that the implicit contract is a surprisingly strong one. Allen, Clark, and McDermed (1995) report that the incidence of post-retirement benefit adjustments in the 1980s, although propor-

TABLE 5-4 The Change in Mean Pension Benefits between 1973 and 1979 as a Percentage of the Change in the Consumer Price Index Among Pre-1973 Retirees, by Plan Size (1979) and Collective Bargaining Status, in Percentages

|

Size of Firm |

With Collective Bargaining |

Without Collective Bargaining |

|

1–99 |

6.3 |

5.2 |

|

100–499 |

18.8 |

26.7 |

|

500–999 |

17.9 |

25.0 |

|

1000–4999 |

13.3 |

15.8 |

|

5000–9999 |

33.3 |

32.5 |

|

10,000+ |

66.7 |

42.8 |

|

SOURCE: Clark, Allen, and Sumner (1986:Tables 13 and 14). |

||

tionately less generous than in the high inflation 1970s, were independent of the financial performance of the pension plan, a result that suggests that firms did not renege on expected inflation adjustments simply because plan performance was poor. (They provide weak evidence that the magnitude of the inflation adjustment was affected by plan performance.) Cornwell, Dorsey, and Mehrzad (1991) find no evidence that firms strategically lay off workers prior to retirement when inflation rates are unusually high so that the "quit" value of the pension is much less than the "stay value." (These terms are more carefully defined below.) Curme and Kahn (1990) find only weak evidence that the likelihood of business failure affects the incidence of pensions (only among nonunion, nonmanufacturing workers is the industry failure rate significantly and positively related to pension coverage rates), suggesting that workers are in general not concerned about this contingency. The data, it should be noted, are drawn from the post-ERISA period (1983).

In a somewhat different direction, Ippolito (1986:Chap. 13) reports that "reversions" of overfunded pension plans—terminating the program and capturing the value of the plan above the level required by ERISA (the pension's quit value), was relatively rare and was frequently accompanied by the establishment of a new plan. Moreover, the probability of a voluntary reversion was not significantly affected by the recent prosperity of the industry. In a more exhaustive study, Petersen (1992) does find modest evidence of strategic reversions that might have breached the implicit contract between firm and workers, at least before a federal excise tax was placed on the activity in 1986. (Ippolito's data were also from the pre-1986 period.) "Firms that are experiencing income short-falls and that are least able to obtain additional funding in the financial markets are most likely to revert their pensions" (Petersen, 1992:1047). As Ippolito

(1986) stresses, it is impossible to know with current data whether this is a loan or a breach of contract. However, Pontiff, Schleifer, and Weisbach (1990) report that reversions are more frequent after takeovers and especially after hostile takeovers, when a breach of the implicit contract would seem most plausible, but the effects are not large: 15 percent of hostile acquirers revert within 2 years of the takeover; only 8 percent of friendly acquirers do so.

THE EMPLOYMENT OF OLDER WORKERS17

Firms differ greatly in their propensity to employ older workers. Before I explore that statement more carefully, it will be useful to decompose the universe of jobs by partitioning firm/worker matches into those expected to be short term and those expected to be long term. In the discussion below, these will be labeled short-term contracts and long-term contracts, although the contract may be an implicit one. For short-term contracts, the duration of the job is by definition limited and the firm can vary the age distribution of its employees only through age-of-hire restrictions. Moreover, short job tenure discourages pension coverage because, in the absence of unions or other trade group organizations, short tenure translates into small pension accounts, which are more expensive per dollar to administer than large ones. Short-term contract jobs are more likely to be part time, and part-time jobs are more likely to be short term, but the linkage is not a tight one. Full-year, part-week jobs are often quite stable over time (Blank, 1989), although even stable part-time jobs are typically associated with relatively low pension coverage.

In long-term relationships, the policy options multiply. As workers age, the firm can maintain them in their long-term jobs, with or without pay cuts; it can reassign them, typically reducing their responsibilities, again with or without pay cuts; or it can release them, with or without pensions. In the absence of legal restrictions, a firm can implement its age policies by rule, across broad classes of workers, or selectively, perhaps screening older workers more intensively than younger ones. Although job reassignment by rule at a given age is not unknown, most rules trigger separation from the firm (mandatory retirement). In another direction, long-term contracts make the provision of pensions less costly. In the dual labor market framework, short-term jobs are more likely to be "bad" jobs and bad jobs are more likely to be short term, but again the association is far from perfect; from jobs in construction to those in economic consulting, job duration may be limited yet the job very lucrative.

Consider now the measurement of employment propensity by age. A plausible, but simple measure of employment propensity by age is the share of the firm's work force that is over x years of age, say 55:

In a stationary world, this measure would appear to capture unambiguously the sense of the firm's age policy on employment, although it is less appealing in a nonstationary one. Because new hires are drawn disproportionately from new entrants, the proportion of new hires that is older will be lower (or higher) in a rapidly growing (or declining) firm than in the steady state. For example, the fact that workers in the farm sector are disproportionately older may say less about the intrinsic employment prospects of older workers in that sector than about the fact that employment in the farm sector has been in secular decline. Conversely a rapidly growing industry will, other things being equal, have fewer older workers.

The S55 measure is strongly and negatively related to both firm size and unionism (Parsons, 1983). The larger the firm size, the lower the fraction of the work force that is composed of older workers. The similarity of the large-firm effect and the union effect on the employment share of older workers suggests that the large-firm effect may be no more than a pension income effect, signifying nothing about firm demand—workers with pensions retire earlier than do those without pensions. If large firms serve as relatively cost-effective financial intermediaries, then by providing pensions they may make early retirement relatively more attractive to the worker. Similarly, if Internal Revenue Service (IRS) nondiscrimination clauses force firms to "oversave" on behalf of some workers, most plausibly low-income workers, then again workers might retire earlier than they otherwise would. Conversely, older workers may retire disproportionately because large firms find older workers especially unproductive, perhaps because of high sorting and reassignment costs. In short, the relative absence of older workers in some workplaces may be driven by supply or demand considerations.

To explore the demand factors that influence the older worker employment share, it is useful to look at the policies that the firm can use to manipulate the fraction of older workers in its work force: (1) the age profile of compensation, which influences voluntary job-departure decisions, and (2) quantity constraints on the employment of older workers, including more or less formal policies on maximum age of hire and/or compulsory retirement. Because of the negative responses of workers to direct wage cuts (W4), firms seem to focus on pension structure and direct age-based hiring and retention practices to alter the worker's employment structure.

Compensation Profiles

In standard labor supply models of retirement, firms monitor the worker's

productivity and, in competitive markets, pass on that value to the worker in the form of a compensation offer. The worker then calculates his or her optimal work strategy based on current compensation and the expected lifetime wage profile. The shape of the compensation profile reflects the firm's estimate of the worker's productivity profile, which in turn is presumably a function of the worker's occupation and education. It may also be a function of the characteristics of the firm. For example, if firms of a particular type are very poor at reassigning workers as the worker's talents and physical and mental attributes change, the worker's wage offer in those firms will decline more precipitously than otherwise, perhaps inducing earlier departure from these firms. The standard argument is that large firms have greater difficulty making idiosyncratic decisions (F3) and may therefore be less efficient at transferring older workers to new positions that maximize their productivities. If this is true, workers in large firms should have greater declines in total compensation with age than do workers in other firms.

There is substantial evidence that long-term-contract firms historically reduced the compensation levels of workers as they aged, almost exclusively through actuarially unfair adjustments to pension benefits that are now illegal. There is also good evidence that these accrual strategies have the expected effects on retirement behaviors (see below and the reviews in Kotlikoff and Wise, 1989, and Quinn, Burkhauser, and Myers, 1990).

The standard wage model is, of course, only one of many, and other models imply quite different firm motivations. An alternative model of actuarially unfair pension structures derives the terminal provisions of employment contracts as an employer-employee response to the incompleteness of the disability-insurance market (see Nalebuff and Zeckhauser, 1985, and Merton, 1985).18 In this environment, actuarially unfair pensions arise in the optimal employment contract as implicit disability insurance: resources are shifted to early job leavers who are disproportionately individuals unable to work because of the early onset of a severe disability. There may be moral hazard problems; workers retire earlier under this incentive system, but that is an unwanted side effect rather than an objective of the firm.

Age-based quantity constraints suffer from no such ambiguity of interpretation. These constraints may restrict hiring practices and/or retention practices, both of which are important in the determination of the share of older individuals in the work force. The two mechanisms are potentially related in an important way; if firms retain workers because of heavy specific human capital investments, they are likely to prefer hiring younger workers to maximize the returns to training. (There is a limit, of course, to this process—very young workers with high intrinsic turnover rates would also be avoided.) In the spot market, of course, only hiring practices are important because, by definition, jobs are of limited duration.

At one level, the crucial policy issue is the share of older workers employed

by the firm; whether a firm employs large numbers of older workers because it hires many older new hires or because it retains many previously employed workers is not important. The openness of the firm to new hires of older workers is crucial, however, to unemployed older workers, so that the analyses of retention and new-hire behaviors hold a policy interest beyond their implications for employment levels. These two quantity constraints are considered in the remainder of this section.

Mandatory Retirement Rules

Because of recent legislation to make mandatory retirement rules illegal, such rules have been the subject of considerable study by economists and others. Most intensely studied has been the motivation for mandatory retirement rules (e.g., Lazear, 1979; Blinder, 1982; see also the literature reviews in Parsons, 1986; Leigh, 1984; and Lang, 1989). Although currently illegal in most circumstances in the United States, mandatory retirement rules surely reflect underlying employer demand considerations that are perhaps only imperfectly legislated away and therefore remain of policy interest. For example, one would conjecture that most "bridge" jobs between career jobs and complete withdrawal from the labor force are not characterized by rules on maximum age of hire or job retention. We return to this question below.

Why are long-term contracts so frequently characterized by fixed-age termination provisions in the absence of government regulation? The most prominent theory of mandatory retirement is that proposed by Lazear. Lazear's basic insight is that mandatory retirement is a quantity constraint, one imposed and enforced by management, so that net compensation at that point in the life cycle must exceed the value of product. This is a special case of the general result of Akerlof and Miyazaki (1980); employment contracts in which wages optimally deviate from productivity will typically require quantity specifications as well as wage specifications. The fundamental issue then is why wage premiums are being paid to workers near the mandatory retirement age and why the restriction on these wage premiums takes the form of an age limitation.

Lazear's discussion of mandatory retirement is diffuse and includes the implausible argument that pensions are deferred payments with the property that they can be altered after retirement to adjust for late-arriving information on worker productivity. More appealing is the proposition that can perhaps be summarized as follows:

-

Compensation grows faster over the life cycle than does productivity because of lifelong monitoring problems: at some point wages exceed productivity as a consequence.

-

The deviation between wage and productivity may lead to a deviation away from the worker's (unconstrained) choice of retirement age.

Under this argument, mandatory retirement rules simply induce workers to retire at the age they would choose if they faced a compensation scheme that reflected their productivity rather than their age.

Blinder (1982) has proposed a variant on argument (2), that the divergence of wages from productivity may be the consequence of specific human capital. The existence of specific human capital, however, does not itself generate overpayment in the final period: as in the Lazear model, additional assumptions on the age profiles of wages and productivity are required. In both cases the models are "completed" with an appeal to the notion that a continuing, indeed growing, gap between wages and productivity requires a well-specified terminal point for the contract to "balance" as it must for a profit-maximizing firm in a competitive market. This argument does not hold in a model that recognizes the existence of disability and death. Even without mandatory retirement, work is not forever. If able to contract freely, employers and workers appear to prefer a fixed-end-point contract, but that is a choice, not a requirement.

In one direct attempt to assess the validity of the Lazear hypothesis, Hutchens (1987) estimates the impact of detailed job characteristics, including an index of work repetitiveness and of firm-specific human capital, on firm personnel policies, including pensions, mandatory retirement, long tenure, and wage rates.19 First introducing work repetitiveness, he concludes, "Within this population of older workers, jobs with repetitive tasks tend to be characterized by low wages, short job tenures, lack of pensions, and absence of mandatory retirement, ceteris paribus" (1987:S163). As Hutchens notes, this pattern of results is consistent with virtually all theories, but he takes special note of the fact that it is consistent with Lazear's "delayed payment" theory of pensions; if the work activity is simple, the malfeasance detection lag should be short. Subsequent analyses by Hutchens in the same paper reveal that the job repetitiveness finding may simply reflect its (negative) correlation with the training and education requirements of the job; when a general educational development index is included, the repetition measure is insignificant and indeed of the wrong sign.

The fact that mandatory retirement rules are disproportionately found in large, unionized firms could be the result of the agency problems laid out by Lazear or Blinders. Alternatively it could be no more than a reflection of the fact that large, unionized firms have more formal rules of all types, itself a reflection of the high cost of dealing with idiosyncratic decisions in large firms. There is strong evidence that large firms have high transactions costs in such matters, including the lack of exceptions to the mandatory retirement rules (see "The Aging Worker and the Firm" above). The number of mandatory retirement plans in the typical firm is one or two (Slavick, 1966), with little or no distinction made across workers in different occupations. A broad distinction is occasionally made across blue collar and white collar workers, with the blue collar workers typically having the later compulsory retirement age.

Other evidence also casts doubt on the Lazear and Blinder hypotheses, at least in the simple form in which they were originally presented. For example, when the minimum legal mandatory retirement age was pushed to 70, a number of researchers predicted that the legislation would have little effect on retirement behavior because the rules were binding on the decisions of a relatively few workers. Most workers covered by mandatory retirement provisions planned to retire by the age at which the original rules would become effective (Barker and Clark, 1980; Burkhauser and Quinn, 1983; Parnes and Nestel, 1981). This prediction seems to have been validated by subsequent events.

The fact that mandatory retirement rules do not appear to be targeted on the average worker suggests, however, that the answer to the question of why mandatory retirement rules exist must be sought somewhere other than the representative-worker models of Lazear or Blinder; the best evidence is that employers can move older workers out of their work places with appropriate uses of the pension carrot if they are long tenured in the firm; the stick is not needed. For excellent reviews, see Quinn, Burkhauser, and Myers (1990) and Kotlikoff and Wise (1989). I argue that the rationale for mandatory retirement lies instead in the age-of-hire heterogeneity of the work force (Parsons, 1991a). The rules are binding, not on the standard case of those with long tenure and comfortable prospective pension incomes, but on those who entered the pension-covered job later in life and therefore carry with them more limited pension rights.20 These rules provide a mechanism for limiting the wage premiums captured by these late arrivals (who will have accumulated less generous pension rights at the traditional retirement age and will therefore be more likely to desire continued employment into their less productive older years).

New-Hire Policies

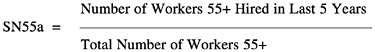

Before I turn to the review of firm new-hire policies and what they imply about the firm's demand for older workers, consider the measurement question. One measure of the firm's desire to hire older workers is the share of older workers who are recent hires, that is, the ratio of new hires of older workers (say hires within the last 5 years) to the total employment of older workers in the firm or industry (Hutchens, 1986, 1987, 1993):

This measure is sensitive to hiring trends in the industry. Firms tend to reduce hiring before they begin laying off workers so that a declining firm or industry will, other things being equal, have a low SN55a measure. An alternative measure that is more robust to recent demand fluctuations would be the following:

This measure norms new hires of older workers by the number of new hires of all workers. Both measures are perhaps best interpreted as an index of the prevalence of long-term contracting in the industry. SN55a, for example, is simply an indicator of how the older worker came to be employed in the industry, as a new hire or a retention, and is silent on the question of how good a provider of jobs for older workers the firm may be.

In a series of studies, Hutchens (1986, 1987, 1993) examines the distribution of new hires of older workers across industries and occupations. Hutchens (1986) creates an index of older three-digit industry and occupation changers as a fraction of all older workers (a variant of SN55a) using data from the 1970 1-in-1,000 census data file. In the 28,000 occupational and industrial cells he created, the index ranged from 0.329 to 1.11.

Examples of jobs with low values of the index are lawyers in legal services and welders in miscellaneous fabricated metals. Jobs with high values include delivery- and route-men in miscellaneous wholesale trade and janitors in medical and other health services (Hutchens, 1986:453).

Hutchens reports that the share of older workers that have been recently hired is highly and inversely correlated with other indexes of long-term contracting, such as tenure, premium earnings, pension coverage, and the presence of mandatory retirement rules. Hutchens specifically notes that this constellation of results is consistent with agency-induced upward-sloping wage profiles of Lazear (1979, 1983), but again it is also consistent with any other long-term contract motivation—it is in fact a measure of long-term contracting. Using both SN55a and SN55b measures, he demonstrates that the new hires of older workers are much more concentrated by occupation and industry cell than the employment of older workers in general or new hires of younger workers (Hutchens, 1987).

In a subsequent paper, Hutchens (1993) creates the same SN55a index, using CPS data in the 1980s, and merges it into the 1988 Survey of Displaced Workers. He then examines various relationships on the merged data, including the impact of age on an index of post-displacement job quality and the impact of pre-displacement job tenure on the size of the decline in the index and compensation between pre- and post-displacement separation. Surprisingly, in a sample of married, male high school graduates, there was no relationship between the post-displacement job index and age. Or as Hutchens (1993:99) remarks, "There is no support for the hypothesis that older workers tend to obtain jobs in industries and occupations characterized by short job tenures." Indeed older workers were more likely to find jobs in their old industry and occupation, though they were also more likely to be not employed. The negative finding on short tenure is some

what puzzling and appears to be inconsistent with findings in the bridge-job literature.

Given the prevalence of long-term contracting in large, unionized firms, it should not be surprising to find that, when legal, large and unionized firms hire relatively few older workers and indeed have formal age-of-hire restrictions. If the system is structured to encourage career jobs, then firms may avoid hiring older workers as an indirect result of their hiring/training system. The bridge-job literature suggests that job openings for older workers are found primarily in low wage/part-time jobs. Unfortunately the focus of this literature has been on the stability of occupation and industry between career jobs and bridge jobs rather than on the size and union status of the job as is the case in the pension literature. As Ruhm (1990:488) summarizes his findings based on data from the Retirement History Survey:

Despite the high financial costs of changing employment sectors, bridge jobs are rarely located in the same one-digit industry and occupation as career employment. Fewer than a quarter (23.9%) of respondents remain in their career industry and occupation in their first subsequent position, and barely half (51.6%) stay in either the same one-digit industry or occupation.

For those who consider themselves partially retired, the percentage who take bridge jobs in the same industry and occupation is only 11.4 percent (Ruhm, 1990:489). "Workers almost never partially retire on their career jobs" Ruhm, 1990:490). Using an alternative definition of career job, Quinn, Burkhauser, and Myers (1990:177) report that only 5 percent of male wage and salary earners in the Retirement History Survey who leave full-time career jobs move to part time status on the career job, less than half the fraction that are part-time on new jobs.21 See Hurd (1993) and Hurd and McGarry (1993) for reviews of this and related research.

A more interesting, but more empirically delicate question is whether large, unionized firms hire fewer older workers, given the firm's contracting status (long term or short). For example, if older job applicants are more heterogeneous, making assessment of their capabilities more difficult, larger firms may be more reluctant than small ones to hire or retain them (Parsons, 1983).

EMPLOYER-PROVIDED PENSIONS

Employers are a major supplier of retirement annuities in the United States. Below I first review what is known about the forces that determine the distribution of employer-provided pensions across sectors.22 I then turn to consideration of recent pension trends. Not all pensions are the same, and discussions of both the point-in-time equilibrium and secular trends would be incomplete without partitioning pensions by type. It is useful to distinguish three types of pension plans: defined benefit plans, traditional defined contribution plans, and 401(k)

plans. Defined benefit plans typically offer the retiree an annuity based on years of service and age, in contrast to defined contribution plans, which are essentially savings plans with investment risk on the worker's shoulders rather than the firm's.23 The employer may not even commit to contributing to the plan on a regular basis; in the recent past almost two-thirds of all defined contribution plans were deferred profit-sharing plans, with employer contributions specified in a variety of ways, including employer discretion, Kruse (1993). Although 401(k) plans have characteristics in common with traditional defined contribution plans, they have unique features that warrant separate consideration. The typical 401(k) plan involves voluntary employee participation in the plan through employee contributions and, in most cases, with employer matching. The 401(k) plans are popular as secondary plans, although our main interest will be in their use as primary plans.

The Locus of Pension Coverage

Consider first the locus of pension coverage without distinguishing specific types. As with age-based hiring provisions, pension coverage is a workplace phenomenon, not an individual one (Slavick, 1966; Parsons, 1992). IRS nondiscrimination rules reinforce the scale and transaction-cost economies that make coverage of employment rules so broad; employer-provided pensions qualify for favorable tax treatment only if they are available to a broad cross section of workers in the workplace.

Although it is not immediately relevant to the discussion, I should note that this workplace-wide characteristic makes problematic the usual interpretation of parameters in pension studies. Treating the estimated parameters in individual-pension-status regressions as individual-demand equations or reduced-form (demand and supply) equations just because the data are individual observations is incorrect in a heterogeneous workplace. For example, as a demand-driven phenomenon, individual pension coverage is the convolution of two processes: the firm's response to the aggregate characteristics of its workers and the worker's choice of firm. In a world of positive mobility costs and varying wage premiums across workplaces, the choice of employer will be driven by a wide range of forces other than pension status. Indeed, at the age many workers settle into lifetime contract jobs, there is little reason to imagine that pension coverage status is a crucial factor. The young are often ignorant of the nature of their pensions (Mitchell, 1988; Gustman and Steinmeier, 1989), an observation consistent with the finding that young workers do not pay compensating differentials for pension coverage (see below). Pension coverage is a function of the distribution of worker characteristics, not of individual ones.

The industrial locus of employer-provided pensions can be explained reasonably well by two factors: the tax advantages that tax deferral offers high-income workers and the economies of scale in pension administration costs that make

pension provisions cheaper the larger the pension pool (the firm or union) (Parsons, 1992. For example, pension coverage is much more prevalent in workplaces characterized by high average earnings and in large, unionized workplaces (Slavick, 1966 Lazear, 1979; Parsons, 1983; Freeman, 1985; Dorsey, 1982, 1987). For additional evidence on the responsiveness of pension provision to tax policies, see Woodbury and Huang (1991) and Reagan and Turner(1995); for a discussion of scale economies in pension provision, see section on ''The Aging Worker and the Firm" above.

That these two factors are sufficient to explain the industrial locus of pension status does not mean that other factors are not important, but that the other factors either are collinear with scale and income or are not of the same magnitude of effect. Chief among the set of alternative hypotheses is the agency argument, most systematically developed by Ippolito (1985, 1986, 1987). Nonvested pensions provide a form of mobility and performance bond.24 Historically, employer-provided pensions were overwhelmingly defined benefit plans, with the firm promising longtime, "loyal" workers the equivalent of an annuity upon retirement, but offering nothing if the worker left without employer approval. Pension bonding of this sort could have a number of objectives, including the following: (1) bonding against union activity (Latimer, 1932; Williamson, 1992; Gratton, 1990; and a variant on this argument by Ippolito, 1985);25 (2) bonding against voluntary job turnover; and (3) bonding against poor job performance.26 Gratton's review of internal deliberations at the Pennsylvania Railroad suggests that the first two objectives may have been especially important in the early development of employer-provided pensions (see also Williamson, 1992).

The importance of private pensions as voluntary job-mobility bonds is currently the focus of debate (e.g., Gustman and Steinmeier, 1995; Allen, Clark, and McDermed, 1993). Before summarizing the elements of this debate, it is useful to recall that pensions as a mobility bond have been severely constrained by legislation in the past two decades. In particular. ERISA has greatly restricted the firm's vesting options, thereby limiting the firm's ability to backload the contract. Prior to ERISA, 40 percent of all pensions were never vested. Now all pensions must be vested in a relatively short time; under recent amendments to ERISA, a firm using cliff vesting, for example, must vest its workers' pensions within 5 years. If the pension is vested, the penalty for quitting a job is more modest, the difference between the quit value of the pension and the stay value (Ippolito, 1986).27 This difference is largely driven by the incomplete inflation protection afforded benefits to those who separate from the firm long before retirement. In the typical defined benefit plan, benefits are payable only after a specified age, with payments based on a measure of final years' earnings. The final years' earnings base provides implicit inflation protection to employed workers, but the nominal earnings of job leavers are frozen in time. Although this quit penalty may be of serious concern to a potential job leaver, the penalty is less

than the total loss of pension rights associated with an unauthorized job departure in an unvested plan.

Accurate measurement of causal influences becomes correspondingly more important, but measurement is a problem here, especially the separation of the mobility-disincentive effect of the quit-stay differential from the pay premium effect of the pension. The existence of a pension plan is correlated with reduced early and midlife mobility (Schiller and Weiss, 1979; Mitchell, 1982). What is less clear is whether this effect is due to a compensation premium or to a specific pension effect. Allen, Clark, and McDermed(1993) believe they have separated these effects successfully and estimate a large disincentive effect. Gustman and Steinmeier (1995) question this finding on a number of grounds, including their own estimates, which suggest a much smaller role for the capital loss effect. They also argue that the losses implied by the quit-stay differential are rather small compared with even a modest raise, the end result, presumably, of a quit. Perhaps most compelling is their finding that the mobility-reducing effect of defined contribution plans, which have no significant quit penalty, is almost identical to that of defined benefit plans, which do (see also Even and Macpherson, 1992). Unfortunately the identification of pension type (defined benefit versus defined contribution) is subject to large errors in these data sets, so the power of this finding is correspondingly diminished.28

Measurement of the pay premium is especially difficult, involving as it does the question of whether the worker is paying for his or her pension through a compensating differential (reduced wages). Although economists are generally willing to assume the existence of compensating differentials, there is little solid empirical evidence of this phenomenon. The majority of the compensating differential studies report small and imprecise effects of pension coverage on earnings, although at least one recent effort finds stronger evidence for such an effect (Montgomery, Shaw, and Benedict, 1992). Because earnings affect pension coverage and pension coverage affects earnings, the empirical analysis inevitably involves instrumental variables and inclusion restrictions that would fail rather modest plausibility standards.

Defined benefit plans can also be used to "gracefully" sculpt the age profile of compensation without inducing serious worker morale problems (W4), and indeed economists have accumulated a great deal of evidence that the structure of defined benefit plans can be used to induce exit from the firm (e.g., Burkhauser, 1979, 1980; Lazear, 1983; Lazear and Moore, 1988; Ippolito, 1986; Kotlikoff and Wise, 1989; and Stock and Wise, 1990. For important surveys, see Fields and Mitchell, 1984; Ippolito, 1986; Kotlikoff and Wise, 1989; and Quinn, Burkhauser, and Myers, 1990). The basic notion is that the age profile of earnings tends to be stable but that variations in the accumulation of pension benefit rights by age can be structured to reduce effective compensation, providing firms with a graceful way to reduce a worker's compensation. For example, it was once common to stop pension accruals at age 65, so that future benefits would not increase with

continued work after 65. The actuarial value of compensation is reduced because pension income is postponed a year, which not only reduces the present value of the benefit flow, but also reduces its actuarial value because of positive mortality rates. With pension benefits of reasonable size, these effects can be very large relative to annual earnings although it should be again noted that the options available to the firm in constructing an age-based benefit are now severely restricted by government regulation.

Kotlikoff and Wise (1989:Chap. 4) present the beginnings of an analysis of how pension accrual rates vary with attributes of the firm and worker although confidentiality restrictions on their data, the Bureau of Labor Statistics' 1979 Level of Benefits Survey, limit firm characteristics to an industry identifier. Kotlikoff and Wise report that pension accrual rates are quite similar across industries (and occupations) for plans with the same early and normal retirement ages. They report large differences across industries in normal retirement age, however, including an especially low "normal age of retirement" in the transportation sector (55 years). The reasons for this differential are not explored. Clearly much remains to be done in this area. A critical question is the economic importance to the firm of this mechanism for reducing worker compensation.

Although defined benefit plans have historically been the predominant form of coverage in the United States, defined contribution plans, often equated with savings plans, have grown rapidly in the last decade. Before a discussion of these trends, it will be useful to consider the factors that determine the industrial locus of pensions by type. In defined contribution plans, the firm's contributions typically vest immediately and lump-sum settlements at the time of job separation are common. Administrative costs are low, even for small plans, much less than those in a defined benefit plan. For plans with 50 to 99 participants, the absolute administrative cost differential between defined benefit and defined contribution plans was equal to $100 in 1985, approximately the same as the total cost of supplying a defined contribution plan. The absolute cost differential is only $39 for plans with 20,000 to 49,999 participants. Defined contribution plans are also more easily transportable across firms, an appealing attribute when firm mobility is intrinsically high as in seasonal work.29

Other factors may also explain the concentration of defined benefit plans in large workplaces. These plans have a number of agency properties that are likely to be more highly valued in large firms; for example, the various bonding and wage-sculpting attributes of pensions discussed in the last section are in fact characteristics of defined benefit plans. However, defined contribution plans may also have agency functions. The great majority of defined contribution plans are deferred profit-sharing plans, with employer contributions based on profits, wages, and simple "employer discretion" (Kruse, 1993). Economists are prone to assume that worker payments contingent on the success of the firm serve to align worker motivations with those of the firm and therefore increase productivity, although Kruse's efforts to measure the productivity effect of profit-sharing plans

are disappointing from that perspective. Estimated productivity effects are positive on average, but the dispersion is large and the magnitude of effect small. Surprisingly, strict profit-sharing plans (employer contributions based on a prespecified profit share) are less productive than those in which employer contributions are at the firm's discretion (Kruse, 1993). Andrews (1992) argues that profit-sharing plans are attractive to employers for a quite different reason, the flexibility of contributions. In a bad year, firms can contribute less to the pension plan, in good years more. This literature has not been integrated with the bonding literature discussed above.

The average 401(k) plan is surely more costly to administer than is a traditional defined contribution plan, simply because the element of employee volunteerism adds an idiosyncratic element to the program, but it also has important coal-saving properties—the employer contributes only to workers who themselves contribute. The targeting effect endows this program with a tremendous total cost advantage over universal plans despite the higher administrative costs. Ippolito (1992, 1994) argues that 401(k) plans have agency effects as well. Specifically. they selectively encourage high discounters, possibly less reliable workers, to choose other employers, both by providing greater compensation to workers who choose to save and by effectively offering cash bonuses to workers who choose to separate now—the bulk of such plans offer lump-sum payment options at the time of job separation. The empirical importance of these effects has not yet been established; disentangling these effects from the targeting effect of 401(k) plans will not be easy.

Primary 401(k) plans are more prevalent in small firms, although perhaps too much can be made of this fact. IRS guidelines for tax-exempt status for this type of pension were not circulated until 1982, and historicity appears to be a major factor in the choice of pension plans. Primary pension plans were already well established in larger firms, and replacing these plans with 401(k) plans would be expensive, certainly more expensive than the adoption of such a plan by a firm that had no plan. That said, 40l(k)-type plans appear to be the pension plan of choice for firms adopting pension plans for the first time, superior to both defined benefit and traditional defined contribution plans.

Trends in Pension Coverage

Much of the recent literature has explored the determinants of two basic trends, a decline in the 1980s in male pension coverage rates and household pension coverage rates and a shift in coverage from defined benefit plans to defined contribution plans. Research in both areas suggests that responsibility for these trends is more or less evenly divided between (1) a structural effect, resulting from changes in industrial structure, and (2) a behavioral effect—changes in firm behavior, given workplace characteristics. The latter may be induced by regulatory changes, of which there have been many in this period, and

by nonstructural changes in the workplace, for example, the squeeze on profits by more intense international competition in the heavy manufacturing sector.

Regulatory changes with direct effects on pension coverage have been both negative and positive. The most obvious trend has been a negative one, the ever-tightening regulatory restrictions on the form of defined benefit plans. Not only have these regulatory shifts limited the usefulness of defined benefit plans to the firm, but the constant flow of regulatory changes has meant that firms with such plans have faced several decades of "one-time" transactions costs in order to bring their programs in line with changing regulations. A positive change has been the innovation in a whole new class of pension instruments, 401(k) plans, which offer important targeting advantages, as was noted earlier. Certainly these regulatory changes are consistent with the almost continuous decline in defined benefit plans as a fraction of all primary plans and the explosion of 401(k) plans, both primary and secondary. Indeed one could conjecture that the permissive legislation on 401(k) plans was a response to the increasing regulatory burden on defined benefit plans.