BIALOWIEZA NATIONAL PARK AND BIOSPHERE RESERVES

Czeslaw Okolow

Bialowiewa National Park

Vjacheslav Vasilievich Semakov

State National Park Belovezhskaja

GENERAL DESCRIPTION

Bialowieza Primeval Forest today encompasses 150,000 hectares on both sides of the Polish and Belarusian border. The Polish (western) part covers 62,500 ha, and the Belarusian (eastern) part, 87,500 ha. Over the course of time, the Forest has developed mature stands of undisturbed origin, a unique phenomen in this European lowland zone of deciduous and mixed forests. These stands developed naturally, practically free of human influence. Local soil and climatic conditions have guided the development of the stands' multi-species and multi-aged structures. The stands also have characteristic spatial distribution and a zonal character of vegetation specific to the post-glacial plains of this part of Europe. These factors have ensured the "biodiversity" of the Forest. Following are some data on the biodiversity:

|

Flora: |

Species |

Fauna; |

Species |

|

Vascular plants |

> 1000 |

Mammals |

62 |

|

Bryophytes |

> 250 |

Birds |

237 |

|

Lichens |

334 |

breeding permanently or irregularly |

167 |

|

Fungi |

> 3000 |

Reptiles |

7 |

|

mushrooms |

450 |

Amphibians |

12 |

|

Myxomycetes |

> 80 |

Fishes |

24 |

|

Aerophytic algae |

156 |

Insects |

> 9000 |

|

|

|

butterflies and lepidopterous |

> 1050 |

|

|

|

beetles |

> 2000 |

|

|

|

hymenopterous |

> 3000 |

|

|

|

dragonflies |

23 |

|

|

|

Snails and other gastropods |

61 |

|

|

|

Spiders |

> 200 |

Because the knowledge of many systematic groups is far from satisfactory, the above data are changed annually based on the results of current investigations. It should be noted that many rare species of Poland and Belarus are found only in Bialowieza Primeval Forest. Just as there are rare or threatened species through the world which are relics of natural habitats, such is the case with primeval forests. One example of such a species is the largest mammal in Europe, the European bison. The ecology of Bialowieza Primeval Forest and the lack of natural ecological barriers or isolation have resulted to many endemic flora and fauna species. But the unusual biodiversity of this ecosystems is exemplified by the fact that over 100 species of cryptogamous plants and invertebrates were first discovered here. In the Polish part of Bialowieza Forest, 25 natural plant communities (16 forest and brushwood, 9 non-forest), 51 seminatural plant communities, and 30 synantropic communities are known.

The extent of the biodiversity in this unique forest ecosystem is still unknown. For example, a study of only one forest section (144 ha) noted nearly 2000 species of cryptogamous plants, and this investigation, due to a lack of taxonomists, was restricted to certain chosen groups. The forest community of Tilio-Carpinetum, in which 425 species of Chalcid-wasps were found, provides another example. The process of differentiation and diversification still continues. The long-term influence of special habitat conditions provide niche characteristics and local ecotypes consisting of several organisms, such as trees like the Norway spruce. Daily investigations of butterflies found local races or subspecies characterized with larger size and darker colorations than those in populations outside forest.

STATE OF PRESERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF ECOSYSTEMS

Polish Part

The Bialowieza National Park, the oldest national park in Poland, was created in 1921 and encompasses 5,446 ha. The main focus of the park is the Strict Nature Preserve, which comprises 4,747 ha. Other components of the national park are the Palace Park (49 ha), the European Bison Breeding Centre (276 ha), and the buffer zone between the Strict Preserve and the surrounding farmland. However, even the largest portion of the park is not big enough to safeguard all the types of flora, fauna, and vegetation indigenous the Polish part of the forest. The Strict Nature Preserve does not, for example, contain a number of the forest communities common to the western part of the forest such as the cowberry pine forest (Vaccinio vitisideae Pinetum). Similarly, it has not been possible to reserve the necessary habitat for large predators. According to a recent study, an adult male lynx in the Bialowieza Forest inhabits a range between 10,000 and 20,000 ha.

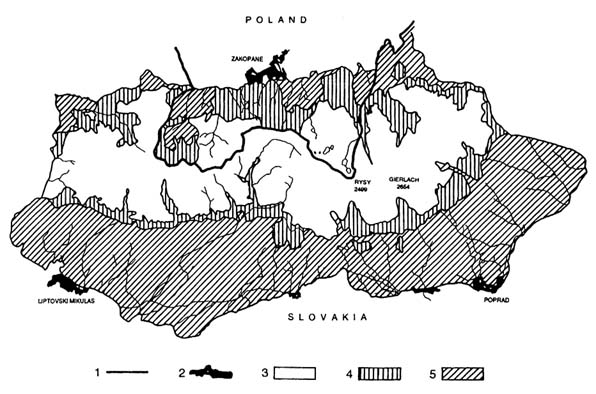

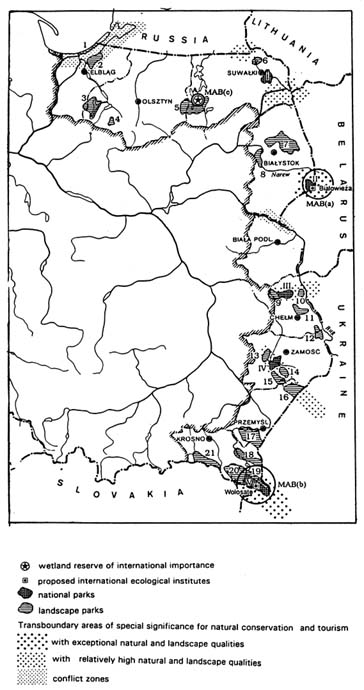

In the managed part (54,255 ha) of the forest, which occupies the remainder of the Polish part of the forest, there are 13 complementary nature reserves covering

2,364 ha, including a Permanent soil Plot (485 ha) (Fig. 1). There are also over 800 individual trees, mainly oaks, which are protected as monuments of nature. Seed stands are another form of protection. However, forests designated for recreation did not guarantee the necessary ecological protection. In the managed forest surrounding the national park, changes are taking place at an increasing rate. A water storage reservoir built at Narew river on the northern edge of the forest (3200 ha) threatens the national park. Another serious threat is air pollution, which not only comes from distant sources, but also from nearby heating installations which use low quality black coal and which are located sometimes less than 1 km from the Strict Nature Preservation.

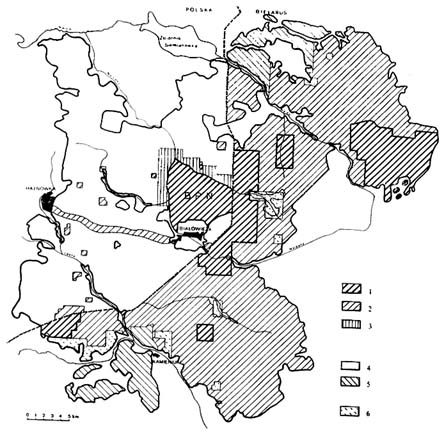

FIGURE 1 Bialowieza Primeval Forest. Categories of Protection and Land Use: 1. Strict Preserve, 2. Partial Preserve, 3. Buffer Zone of Strict Preserve of BNP, 4. Managed Forests, 5. Intensive Tourism and Recreation, 6. Traditional Farmland and Cattle Breeding

Since 1977, Bialowieza National Park has been designated as a biosphere reserve. However, it contains only the core zone without other zones with different levels of protection and human activity. In 1979 it was designated as the only natural World Heritage Site in Poland.

Belarussian Part

In the eastern part of the Bialowieza Forest, a ''zapovedenik" (the Strict Nature Preseve) was established after the war. Later, in 1957, a hunting and nature protection unit was set up to serve primarily as a hunting ground for officials. In 1991 it was designated a national park. The park consists of 87,500 ha, of which 15,600 ha are under strict protection, 57,000 ha are partially protected, and 11,300 ha are designated for public tourism and recreation. There is also a zone of traditional farmland and cattle breeding (3,900 ha). A buffer zone of 82,000 ha surrounds the park.

Today, the National Park "Belovezhskaja Pushha" is the only one in the Belarussian forest complex with mature stands (52 percent of the stands are over 100 years old). There are 48 species of plants listed in the Red Data Book (25 percent) and 82 species of animals. The only natural population of silver fir in Belarus is in this Forest, along with the largest herd of free-roaming European bison. In December, 1992, part of the park was joined with the World Heritage Site in Poland to create a unique international European environmental site. In 1993, UNESCO designated it a biosphere reserve. In a survey of the threats to the Belarussian biodiversity, it is necessary to mention the density of the red deer population. These and other game animals have had a negative influence on the structure of the stand. In addition, a 2-meter high fence along the national border serves as an artificial barrier for most of these animals as well as for the European bison.

SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

The following factors cause Bialowieza Primeval Forest to be a special research:

-

The exceptional natural state of the ecosystems, which have been altered only minimally by human activity;

-

The strict protection of large areas (especially in Bialowieza National Park), which allow the possibility to conduct long-term investigations on permanent study plots;

-

The presence in this Forest of complex zones which have varying levels of protection and human activity. Such zones include strict reservations, partial reservations, managed forests, forests designated for public tourism and recreation, and traditional farmland;

-

The biodiversity and genetic materials as well as numerous rare and endangered species of plants, fungi, and animals which are often relics of primeval forests;

-

The exceptional biogeographical setting within the natural distribution range of numerous species of plants, animals, and types of vegetation; and

-

The existing wealth of printed materials and documentation of the various studies conducted over almost a century.

Publications on Bialowieza Primeval Forest include the four volumes of "Bibliography of Bialowieza Forest" (Karpinski J. J., Okolow C. 1967, Okolow C. 1976, 1983, 1991); the fifth volume of this bibliography is now at press. There is also an bibliography of the Belarusian part of the Forest (Koval'kov M. P. et all 1985). There are over 3,900 publications which present the results of various original investigations conducted in Bialowieza Forest. (Over 1,600 include the Bialowieza National Park).

Polish Part

Thanks to the creation of Bialowieza National Park in 1921, today there are five scientific institutions in surrounding villages: the Department of Natural Forests, the Forestry Research Institute, Bialowieza Geobotanical Station of Warsaw University, the Mammals Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Science, the Laboratory of Plant Population Demography of the Polish Academy of Science's Institute of Botany, and the Workshop of Ecology and Protection of Natural Habitats. Bialowieza National Park also has its own small research unit. In addition to the local research organizations, scientific institutes from all over the country carry out projects at the National Park. The Scientific Council of Bialowieza National Park (an advisory body for park authorities) coordinates all investigations in the park. Changes in stands free from human impact are investigated at numerous long-term research sites, the oldest of which date from 1936. Editors of scientific papers such as "Acta Theriologica", "Phytocoenosis", and "Parki Narodowe i Rezerwaty Przyrody" (National Parks and Nature Reserves) are in Bialowieza, where the results of the studies are published. Such papers are also presented during numerous seminars carried out in the park. Finally, Bialowieza National Park is the editor of European Bison Pedigree Book.

Belarussian Part

The national park "Belovezhskaja Pushha" has its own research division which conducts research on topics such as climatology, flora, vegetation, and zoology, with special attention to select groups of insects, birds, mammals and European bison. Investigations of the forest structure are carried out at permanent research sites, the oldest of which have existed for nearly 50 years. Until now, external scientific institutes were not engaged in research in the National Park. However,

interest in this unique research environment is growing, and if more funding becomes available, the number of institutes conducting research in the park will be increase.

All investigations are accomplished under the coordination of the Scientific Council. In addition to the different research projects conducted in the park, the annual "Nature Chronicle" contains numerous systematic data concerning the course of phenology and other natural phenomena such as numbers of game and predatory animals or oak acorn crops. Employees of the national park participate in conferences and seminars where they present investigation results. The national park "Belovezhskaja Pushha" publishes its own periodical paper. Between 1958 and 1976, it issued a periodical called "Belovezhskaja PushhaIssle dovanija," which, since 1977, has been published under the name ''Zapovedniki Belorussii Issledovanija." Its contents include materials from all protected territories in Belarus.

TRANSBOUNDARY COOPERATION

The oldest area of cooperation is associated with the breeding of European bison. In 1961, the first Polish-Soviet conference on this subject took place, with subsequent conferences in 1963, 1967, and 1971. Irregular meetings have also been held without closer practical cooperation. Today, the situation is different. Directors of both national parks are officially members of the Scientific Councils of the park on either side of the border. Thanks to the support from GEF, a unified investigation was begun of air pollution and the impact of pollution on chosen indicator plants. Wide-ranging research on the genetics of native tree species was also begun, and the genetic bank was established. Traditionally, work has been coordinated on the ecology, biology, and physiology of the European bison. The year 1993 marked the beginning of the cooperative investigation using telemetry of the migration and range of wolves and lynxes. Signed in 1993, a protocol of cooperation for the park dictated that the park's employees can visit either part and participate in scientific conferences organized in Bialowieza or Kamieniuki. Employees can cross the state borders in the forest without an official border pass. Currently, the Academies of Sciences in both countries are trying to set up an international ecological institute located in Bialowieza Primeval Forest.

Management and protective measures on both side of the border must be coordinated in order to allow the development of cooperation in the field of protection and investigation in Bialowieza Forest. It is necessary to find uniform methods of scientific investigation which enable researchers to compare results obtained in both parts of the forest. It is especially important to prepare a unified classification of vegetation. Because both countries currently use completely different geobotanical methods, the results of the work (vegetation maps) cannot be compared. Another problem vital to practical cooperation is the communication between management authorities of both parks. (Today, the only fail-safe method

of communication is telex. Other methods, for example, by telephone, take too much time and are not reliable.)

REFERENCES

Koval'kov M.P., Baljuk S.S., and Budnicheanko N.I. 1985 Bialowieza Primeval Forest. An Annotative Bibliography of Homeland Literature (1835-1983) ed. V.I. Parfenov, Minsk (Russian).

Karpinski J.J., Okolow C. 1967 Bibliography of the Bialowieza Forest (up to the end of 1966), Warsaw. (Polish with English and Russian summary).

Okolow C. 1976, 1983, 1991. Bibliography of the Bialowieza Forest. Bialowieza, Part II. 1967-1972, Part III. 1973 1980, Part IV. 1981 1985. (Polish with English and Russian summary).

THE TATRA NATIONAL PARK AND TRANSBOUNDARY BIOSPHERE RESERVE

Zbigniew Krzan

Tatra National Park

The 217 km2 Tatra National Park (TNP), created in 1954, is now one of the largest of the 19 national parks in Poland. To the east, south, and west, TNP adjoins the Slovak Tatra Park, which is located across the border. The city of Zakopane and the Podhale region lie close to the northern park border. The lowest point of the park is 850 m above sea level, and the highest point, Mount Rysy, is 2,499 m above sea level.

The eastern part of the TPN, the "High Tatras," is predominantly composed of crystalline rocks (granite) and has a typical high-mountain glacial landscape with pointed peaks and a large number of lakes. The largest lake is Morskie Oko, which covers 35 ha, while Wielki Staw Polski is the deepest, with a depth to 79 m. The "Western Tatras" are mostly composed of limestones and dolomites and have typical karstic relief with underground streams and about 500 caves. The zonation of plant communities is clearly visible in TNP and is closely related to altitude. The lower slopes are dominated by mixed forests which are structurally and ecologically diverse. Tree species include beech, silver fir, spruce, sycamore and many other woody plants. In addition, the area has secondary spruce forests, artificial stands vulnerable to disease, infestations of insects, and other problems associated with monocultures. Growing higher up, from about 1,250 meters above sea level, are coniferous stands of spruce and arolla pine. Most of this upper forest is natural or seminatural. Above the timber line (at about 1,500 m above sea level), these forests gradually merge with a zone dominated by dwarf mountain pine. In turn, towards the tops of the ridges and peaks, the dwarf mountain pine is replaced by alpine grassland and arctic-alpine communities associated with bare rock and scree. The area has many plant and animal species, including Tatra or Carpathian endemics, glacial relicts, and many endangered or rare species.

The Tatra National Park is accessible for tourism, recreational skiing, and other sports. There is a well-developed and permanently-marked trail system for summer hiking, which has a total length of about 250 km and various levels of difficulty, ranging from typical walking paths to routes for experienced alpine climbers only. Park regulations permit tourists to walk on marked routes only, and

a fee is collected for entering the park. The developed tourist infrastructure is present in the town of Zakopane and nearby villages. The mountains themselves have a system of hostels and lodges which are open year-round, while the Park borders have parking areas, viewpoints, and restaurants. Both a cable car and chair lifts to Kasprowy Wierch summit allow those with different levels of expertise to participate in recreational skiing. There is also well-developed infrastructure for competitive skiing just inside the border of the park, with ski jumps, slalom slopes, down-hill runs, and cross-country areas. There are also designated areas for mountain climbing, with training centers and camping sites at various elevations.

The Park has a visitor center and a program for ecological education. The center introduces visitors to the environment of the Tatras, the history of its protection, and current nature conservation problems through both permanent and temporary exhibitions, videos, and occasional lectures and slide presentations. The visitor center is surrounded by a garden which, by simulating the Tatra plant zones, allows educational activities to be organized for schoolchildren and interested groups of specialists. The guide center also provides information and sells publications concerning the mountain environment.

Acting through four main departments (Forest Management, the Research Station and Museum, Touristic and Nature Protection, and Administration), the National Park Authority works towards the elimination or reduction of human activities, such as tourism and air and water pollution, which are likely to cause conflict with nature conservation.

To achieve effective protection of TNP and its wildlife, it is essential that modern conservation legislation be in place. In 1991, a new state law on nature was passed which places the park management in a better position to negotiate with individuals and organizations concerned primarily with economic gain from activities in the park. The new law also enables TNP to exert influence over economic activities and development in areas next to the Park which could have an impact on the Park itself. In addition to effective legislation, a long-term management plan is needed which incorporates detailed plans for different habitats and threatened species or features. Plans for various aspects of management have already been drawn up, while others are still in preparation. To manage the National Park effectively, these different plans must be integrated in a single general strategy for the Park. Such a strategy, entitled a "Protection Plan for the Tatra National Park," is now in preparation.

Finally, the Polish and Slovak Tatra National Parks have been approved as an International Biosphere Reserve within UNESCO's MAB Program (figure 1). The idea of establishing a Biosphere Reserve in the Tatra Mountains originated in the 1980s in the National Park Councils of both the Polish and Slovak areas of the mountains. Groups of experts began to work on a concept for a future Biosphere Reserve covering both National Parks. Park areas which are most valuable and least transformed by man have been included in the core zone of the Reserve, while surrounding areas constitute a buffer zone. Zonation became the subject of numerous consultations and negotiations aimed at obtaining a single, dense core

numerous consultations and negotiations aimed at obtaining a single, dense core representing all the ecosystems which are most valuable and most characteristic of the Tatra Mountains. The Biosphere Reserve also has a transitional and cultural zone which includes traditionally developed areas. The Tatras are known for an unusually colorful folklore which is still active. The folklore is unique to the four cultural regions surrounding the Tatra Mountains: Podhale, Spisz, Orawa, and Liptow.

The joint work has resulted in a designated Biosphere Reserve covering 145,600 hectares, of which about 20,000 hectares are in Poland. One third of the area is within the core zone. This is a homogenous area, with a similar history of exploration, protection, and development on both sides of the border. The bilateral MAB Biosphere Reserve is the reward of the nearly two centuries of the endeavors of generations of Poles and Slovaks to attain the most efficient protection of the exceptionally valuable features of these unique mountains.

The Biosphere Reserve concept not only incorporates enhanced protection for the most sensitive areas in Park (where human activity should be strictly limited), but also encourages the conservation of cultural landscapes and traditions, such as pastoralism and sustainable forestry. Biosphere Reserve status has not precluded tourism, sport and recreation, which in fact continue. The concept of the international Polish-Slovak Biosphere Reserve should help to ensure harmonious coexistence between the local community and the protected wildlife and wilderness quality of the Tatra Mountains, as well provide a good example of effective cooperation between Poland and Slovakia in the field of nature conservation.

PROBLEMS OF NATURAL DIVERSITY PROTECTION IN THE TATRA NATIONAL PARK AND BIOSPHERE RESERVE

Zbigniew Krzan, Pawel Skawinski, and Marek Kot

Tatra National Park and Biosphere Reserve

Like the rest of Poland, the Tatra Mountains lie in the temperate climatic zone. This means that forests constituted their natural primordial vegetation cover. However, the high-mountain character of the area has ensured that the Tatras have considerably greater natural diversity than other regions of the country. The geological structure, relief, climate, and water relations in this area have influenced the richness of a specific vegetation and fauna. The high natural diversity of the Tatras has been a product of both natural variation and changes brought about by centuries of human intervention with nature in the area.

NATURAL DIVERSITY

The current geological structure of the Tatras is the result of long-lasting development. Acid, decay-resistant metamorphic and crystalline rocks constitute the core of the mountains. On the north side, this crystalline core is overlain by folded sedimentary rocks from the Mesozoic Era. These strata are composed mainly of limestones, dolomites, sandstones, and shales, which create a mosaic of very varied lithology. This lithological diversity has found its reflection in the diversity of soils developed on the substratum of these rocks.

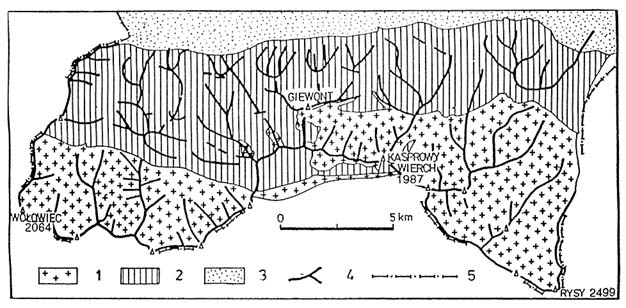

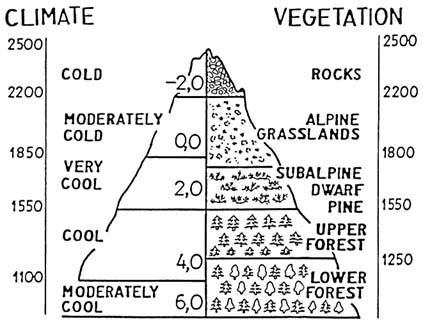

Residual fragments of Pliocene relief do remain in the Tatras, but the dominant relief was established in the Pliestocene as a result of the actions of glaciers. The lower sections of glaciated valleys were modified by fluvioglacial waters, while small unglaciated valleys were the result of the action of fluvial processes. Areas built from carbonate rocks exhibit karstic relief, with typical phenomena such as karstic springs, caves, and karst microrelief. This relief is currently being modified by contemporary morphogenetic processes (Kotarba, 1992) (Figure 1).

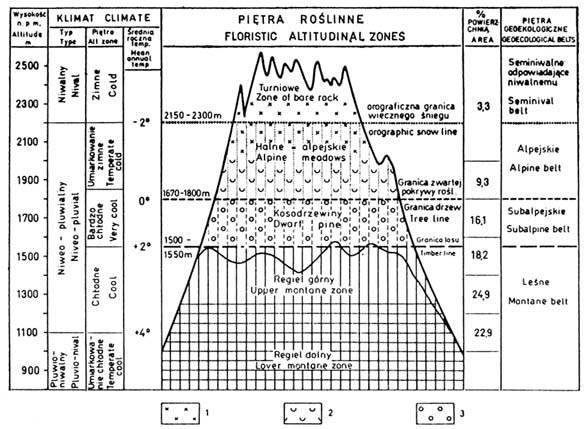

The climate of the Tatras is the result of the situation of the latitudinal mountain chains within the Carpathian are of central Europe. The mountains are located in the transitional zone between two types of climate (the polar-marine and the continental), and this has favored the creation and maintenance of higher biodiversity. In turn, the significant elevation of the Tatras is an important factor which differentiates mean annual temperatures along an altitudinal gradient and which results in the separation of altitudinal climatic belts. The great variety of landscapes gives rise to varied mesoclimatic conditions and the wide and mosaic-like variation in microclimatic conditions which are of overriding importance for biodiversity (Niedzwiedz, 1992).

The Tatras are characterized by a diversity of hydrographic phenomena, including permanent and periodically flowing streams, springs, underground flows, ultraoligotrophic high mountain lakes, and a smaller number of dystrophic lakes. The waters of the Tatras show typical features of mountain areas, including low temperatures, streams with high levels of oxygen, and lakes that are nutrient-poor and icebound for long periods of time. Simultaneously, however, variable climatic conditions and quality of the substrate have given rise to the great natural variations in the conditions for aquatic organisms in the different basins. The lakes of the Tatras are mostly isolated from one another, and this is a factor explaining the occurrence in them of rare communities of aquatic organisms.

As a consequence of the diversity of the abiotic environment, the Tatras are also highly varied floristically and faunistically. Altitudinal zonation is the most characteristic feature of the vegetation (Figure 2). The lower parts have lower montane mixed forest with a significant degree of biodiversity. Beech, fir, spruce, sycamore, and other species of trees grow in such areas, as well as a rich understory. Also occurring in this zone are the secondary stands, monocultures of spruce which remain as a result of the past industrial exploitation of the forests. Higher up, above 1250 meters above sea level, is the spruce-dominated upper montane forest. Stone pipes sometimes also occur in this belt. The majority of these forests are of natural character.

A belt of dwarf mountain pine occurs above the timberline in the Tatras (at altitudes of around 1550 m a.s.l.). Extending above this is a zone of alpine grassland meadows, and farther above this, arctic-alpine communities associated with summital zone of bare rock and scree. Plants occurring in the Tatra National Park include those encountered in the lowlands as well as typically montane species adapted to life in the difficult climatic and soil conditions (Mirek & Piekos-Mirkowa, 1992).

Good conditions for a considerable number of animal species are created by the variations in vegetational environments and by the limited degree to which these have been degraded. Occurring here are animals once widespread throughout the country but later restricted by man to less accessible terrain. Examples of these are predators like bears, wolves, lynxes, and golden eagles, as well as numerous species restricted to high-mountain areas, of which the most

FIGURE 2 Zonality in the Tatras

notable are the chamois and the alpine marmot. The natural faunistic richness of the Tatras is exceptional by international standards (Glowacinski & Makomaska-Juchiewicz, 1992).

SECONDARY DIFFERENTIATION

The natural diversity of the Tatras has undergone far-reaching modifications as a result of diverse human activities. Some of these have resulted in increased biodiversity, while others have impoverished nature in the Tatras in a significant way. While human management of the lands that are now Poland has been continuing for over 15,000 years, its influence in the Tatra Mountains was not clearly felt until the thirteenth century, when settlers bent on developing pastoral life appeared at the foot of the mountains. Settlement took place at least half a century after that in the Polish lowlands. Significant settlement and shepherding were only in evidence in the area from the sixteenth century onwards. However, grazing thereafter constituted the main form of economic utilization until as recently as 1960 to 1980, when gradual limitation occurred as a consequence of

the purchase of the alpine meadows from private hands and the increasingly uneconomic nature of this type of management. Pastoral life in the Tatras is now carried on in a limited way as a cultural activity.

The most important effect of grazing on nature in the area was the felling and burning of forests to enlarge grazing areas. The grazing of sheep led to penetration of the Tatras from the piedmont (at 900 m) to the zone of mountain meadows at 2300 m. In woodland clearings, grass was fertilized naturally, cut, and taken down to the villages at the foot of the mountains, where it served as winter fodder. This activity lasted for several centuries and resulted in the creation in clearings of seminatural communities with light-demanding vegetation requiring a fertile substrate. Floristic and faunistic components entered the clearings from meadows, herb communities, light alder woods, and lichenaceous grasslands. It is probable that some components of the flora (for example, the crocus) were brought in by shepherds but are now totally adapted to life in the Tatras. This type of management undoubtedly led to the destruction of forest vegetation, but on the other had, it also had a colossal impact in enriching the floristic and faunistic biodiversity of the area. It is true that the natural timberline has been lowered along 70 percent of its length (in some places, even by 300 m) and that the area of the belt of dwarf mountain pine has been reduced by about 30 percent. However, it is also true that possibilities have a the same time been afforded for the development of floristically-rich grassland communities.

From the fifteenth century onwards, industry joined settlement and shepherding as one of the human activities in the Tatra Mountains. The area's forests were the raw material base for this expansion, which was to embrace mining, steel making, and the timber industry. The exploitation of trees was mainly concentrated in the more easily accessible, multi-species stands of the lower montane forest, where faster-growing spruce was increasingly introduced.

Industry in the mountains gradually ceased to be a viable economic proposition, and as the associated activities ended, the transformation of forests also ceased. Nevertheless, the effects of several centuries of industry can still be seen in the form of widespread deforestation and the considerable area of artificial monocultures of spruce which occupy rich mixed-forest habitats alien to them. The result of this has been the drastic impoverishment of the floristic and faunistic diversity of large areas of the Tatras, and, as a further consequence, the now clear sensitization of this impoverished lower montane forest to the action of destructive factors, especially the most dangerous, air pollution (Mirek, 1992). The issues presented here are only two of the many and are cited to illustrate the different effects of human activities on nature.

THE PROBLEMS OF PROTECTING BIODIVERSITY IN THE TATRAS

The first activity for the protection of biodiversity should be the definition of the scope and limits of the natural diversity which is to be subject to protection. Protection should not extend to everything which provides secondary enrichment of nature int he Tatras, but neither should all the artificially induced phenomena of elevated diversity be eliminated. The questions which arise are therefore which particular facets of diversity should be protected, and in which regions. Whatever the answers, they will always be arbitrary, but they should at least result from scientific analysis of the problems.

The clearings in the Tatras provide an excellent example. On one hand, they serve biodiversity in an outstanding way, but on the other, they are formations that have arisen artificially as a consequence of the past economic utilization of the mountains. Should they then be left to be eliminated naturally, or should they be protected via human intervention in natural processes? And if the choice is made to protect them, then what is the motive? Is it merely for biodiversification? Other protected areas are witnessing the elimination of so-called ''weeds," exotic species of trees and shrubs, and of their animal equivalents introduced by man. This is done in spite of the fact that these weeds enrich biodiversity. Perhaps a reason for the protection of the clearings should be the fact that they were created a long time ago. In these circumstances, there arises a question as to the age limits for features of biodiversity that are to be protected. Is it to be 10, 100, or 300 years, and if one rather than another, then why? Finally, a reason for protecting the clearings might be their landscape and economic functions. But in this case, why not also extend and utilize them?

Sometimes the need to increase natural diversity in the Tatras does not create such controversies. An example here might be replacing artificial forestry monocultures with more natural mixed forest. It is, after all, clear that the latter will be more appropriate to the habitat, will show greater natural stability, and will in addition be more attractive in terms of landscape.

However, questions arise here, too, albeit ones of a technical nature concerning the way in which the reconstruction is to be achieved. Should the work involve the intensive forestry associated with the gathering of seeds and the cultivation, introduction, nursing, and protection of seedlings and saplings? Or should it happen via a longer route, leaving spontaneous natural processes to take their own course? In the latter case, it is necessary to be aware of the fact that the return to the natural state will take an unusually long time, will involve different successional stages, and will necessitate the protection of all natural factors and influences, including those destructive to the forest like windthrow, disease, and infestations of insects. So in this case, the area will need to be embraced by strict protection, with all the consequences that this has.

A PLAN OF PROTECTION

As in other protected areas, the protection of the natural diversity of the Tatrzanski National Park raises many questions and concerns and not-easily-resolved dilemmas: what to protect, why to protect, and how to protect? Such decisions, however well founded on solid scientific bases, will always be arbitrary in the end, and the goals should be made more precise in a protective plan. TNP is now preparing its own plan of this kind and will define therein the particular natural objects in the Park for which the main aim of protection will be to preserve natural diversity. For each of these objects, there must be a strictly defined and concrete aim for active protection, as well as definitions of the types and scope of the steps to be taken to achieve this aim. The introduction for realization of the plan of protection should be followed by active protective measures which must be subject to constant control in the form of monitoring observations. The plan itself must be modified continually in relation to the effects of the measures applied.

CONCLUSIONS

-

The current natural differentiation of the Tatra Mountains is the result of natural biodiversity and human activities over long periods of time.

-

The high natural biodiversity is an expression of the unusually complex geological structure, the varied relief, the specifics of the climate, the multiplicity of aquatic phenomena, and the richness of the vegetation cover and fauna.

-

Human influences on nature in the Tatras have had various effects on biodiversity. Some, like shepherding, enriched the area's vegetation and fauna, while others (for example, industry) had a decisive effect in limiting the diversity of nature.

-

The protection of the biodiversity of nature requires the making of arbitrary decisions to define the particular objects which should receive such protection, as well as precise definitions of the aims of protection and the ways in which this is to be realized.

-

The active protection of biodiversity in the Tatras will be one of the basic elements of the plan for the protection of TPN. As they are implemented, the aims and principles outlined in this plan must be subject to continuous control in the form of an extensive system for the monitoring of nature. In the light of the effects of the actions outlined, the protective plan must then be subject to periodic updating and modification.

REFERENCES

Glowacinski, Z., Makomska-Juchiewicz, M., 1992, Fauna of the Tatra Mountains. Mountain Research and Development, 12(2), pp. 175-191

Kotarba, A., 1992, National Environment and Landform Dynamics of the Tatra Mountains. Mountain Research and Development, 12(2), pp. 105-129

Niedzwiedz, T., 1992, Climate of the Tatra Mountains. Mountain Research and Development, 12 (2), pp. 131-146

Mirek, Z., Piekos-Mirkowa, H., 1992, Flora and Vegetation of the Polish Tatra Mountains. Mountain Research and Development, 12(2), pp. 147-173

THE FUNCTIONING OF THE GEOECOLOGICAL SYSTEM OF THE TATRA MOUNTAINS

Adam Kotarba

Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization

Polish Academy of Sciences

The massif of the Tatra Mountains meets most of the conditions needed to qualify it as a high-mountain area. Therefore, it may be recognized as the only such area in Central Europe besides the Alps (Troll 1972). The high-mountain character of the natural environment of the Tatras is defined by the following: hypsometry (relative altitudes, and the length and inclination of slopes); geomorphology (classic glacial relief with the group of forms created by mountain glaciers); climate (altitudinal differentiation of climatic parameters); and flora (altitudinal zonation of the natural vegetation) (Fig. 1).

The Tatras differ from classic alpine ecosystems in the incomplete development of the nival altitudinal zone. However, a seminival zone representing a variety within the nival type does exist, and it occurs in mountains lacking the appropriate geomorphological conditions for the development of snowfields and glaciers (Hess 1965). The seminival or bare rock zone is peculiar to the Tatra Mountains, occurring in neither the highest glaciated mountains of Europe, nor the mountain massif elsewhere in the Carpathian-Balkan arc but lower than the Tatras (Pawlowska 1962). It is also difficult to separate the subnival altitudinal zone, which lies between the snowline and the alpine zone identified by the range of the more or less complete cover of soil and vegetation (the "high alpine zone" in the Alps.) From the geoecological point of view, the features characteristic of this zone are present in the Tatras in an altitudinal belt slightly above and slightly below the orographic boundary of the snowline, which occurs at an altitude of 2150 to 2300 m above sea level. This zone is characterized by the presence of frost debris and contemporarily-developing structural soils. Floristically, this corresponds to the zone of open pioneer vegetation.

The feature identifying the Tatras most closely with the Alps is a well-developed zone of alpine meadows. However, this zone does not occur immediately above the treeline, but rather is separated by the zone of dwarf mountain pine, which is again a feature unique to the Tatras.

Although relatively small in comparison with Europe's other high mountains, the Tatra Massif nevertheless represents a significant climatic barrier to masses of air penetrating from the north. A consequential characteristic feature of these mountains is therefore the high annual, monthly, and daily rainfall totals (with the last particularly evident in summer). There is a considerable difference in the amounts of atmospheric precipitation reaching the northern and southern slopes of the Tatras. The maximum annual totals—on the order of 1600 to 1900 mm of precipitation per year—are noted on the slopes with a northern exposure and at altitudes of between 1400 and 2000 m above sea level. (Niedzwiedz 1992). The greatest daily fall of summer rain was 300 mm, noted at Hala Gasiennicowa in the High Tatras on June 30, 1973. However, daily falls exceed 200 mm about once in 50 years and reach or exceed 85 mm every two years at the altitude of the treeline (Cebulak 1983). The action on the substrate of elements of the climate (heat, precipitation, snow cover, and wind) leads to its destabilization and a reduction in its resistance to the destructive processes widely understood as erosional. Particular geoecological belts of the mountains differ in the geomorphic processes controlled by the climate, vegetation cover, geological and soil conditions, and in the ways in which they are affected by these conditions.

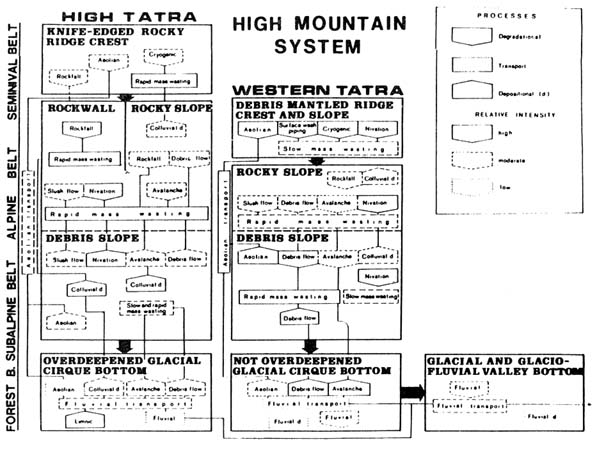

Consideration of the intensity, duration, and vertical differentiation of processes occurring in the Tatras allows one to determine whether the processes are altitude-related or not. Additionally, consideration of these factors permits recognition of processes of short duration and high intensity that create relief, as well as recognition of processes acting continuously but with moderate or weak intensity. Altitude-related processes limited to the geoecological zones above the timberline include frost creep, free and bound solifluction, a group of nivational processes, and deflational/aeolian processes. Processes not related to altitude, or those which may occur at all geoecological altitudinal belts of the Tatras, include physical weathering and rockfalls, chemical denudation, slope wash, and linear/fluvial erosion, soil creep, and talus creep.

The geomorphological activity of avalanches and debris flows is possible in two or three altitudinal zone, especially in those above the timberline. The range of influence of the high-mountain morphogenetic system is presented in Fig. 2. Detailed research into the course and intensity of contemporary geomorphic processes in the Tatras shows that the different geoecological zones are vulnerable to differing extents to their destructive or constructive action (Kotarba 1976). Geomorphic processes of high intensity create micro- and mesoforms within slopes and valley bottoms. Falls of debris, avalanches of snow and earth, and rockfalls transform scree slopes. These falls can create either erosional troughs, depressions, and niches, or they can create hummocks, levees, and accumulation tongues. These forms are created in the course of a few minutes and may change the relief of a slope so significantly that it may alter local topographic conditions.

The morphological consequences of the action of these fall processes remain visible to the naked eye for hundreds of years. Their ages may be defined with the aid of lichenometric dating (Kotarba 1989). Many of the forms created by these high-energy processes originated in the period of the Little Ice Age, especially during its decline in the first half of the 19th century, when a clear deterioration in the climate was observed generally around the world. At this time in the Alps and other glaciated mountains of the world, the largest advances of glaciers in the last 10,000 years were observed. In the Tatras, however, the effects were restricted to intensified alluviation of the high-mountain slopes, which manifested itself through frequent and high-energy geomorphic processes of the debris-flow, avalanche, and rockfall types. Processes of these kinds have been clearly limited for much of the 20th century. However, a tendency towards the renewed enhancement of the alluviation of debris slopes has been noticed in the last 15 to 20 years (Kotarba & Stromguist 1984; Kotarba 1989).

Table 1 presents the main processes leading to the transformation of Tatra debris slopes in the different climatic and altitudinal zones. An index of the activeness of processes, based on long-term measurements of their intensity, shows clear vertical differentiation. The highest values are attained in the section between 1550 and 1850 m above sea level, which is in the very cool climatic zone and which coincides with the cover of dwarf mountain pine. Similar, but somewhat lower, values were calculated for the zone at an altitude between 1850 and 2200 m above sea level in the cold zone with alpine meadows. This indicates that the area of the Tatras located directly above the timberline is particularly threatened by natural geomorphic processes which produce significant transformations in the geoecological system. Thus, it is especially important to realize that the earliest and clearest environmental impacts of changing global trends in climatic indices will be visible in borderline landscape/altitudinal zones, particularly in the timberline zone. The fact that intensified alluviation has been noted in the last 15 to 20 years in areas of the northern slopes of the Tatras above the timberline may thus be a signal that such changes are occurring in the mountains of the temperate zone (Kotarba & Stomguist 1984).

There are significant changes in the relief of the Tatras at altitudes between 1550 and 1850 m above sea level. In the Slovak part, the debris flow tracks are as long as 2 km (Nemook 1982). Janacik (1971) described a catastrophic debris flow which occurred in the Osobota Group of the Western Tatras in July 1970. This flow shifted a 21,675 m3 mass of debris. According to Midriak (1984), the greatest volume of debris ever transported in Tatra debris flow tracks was 25,000 m3. However, in the last decade, large debris flows have occurred with increasing frequency in an area above the timberline around the Research Station of the Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization of the Polish Academy of Sciences, which is located at Hala Gasienicowa in the High Tatra. Masses of debris of 5000 m3 each were eroded and displaced along the routes of several debris flow tracks created during this period. These amounts are small in comparison with those in the Alps, where a single catastrophic debris flow may involve the

TABLE 1 Dominant Morphogenetic Processes on Basal Debris Slope Forms in the Polish Tatra Mountains

|

Present-day activity in vertical climate zones |

|||||||

|

Principal factor |

Principal transfer process |

Principle slope form |

temperate cool 900-1100 |

cool 11001550 |

very cool 1550-1850 |

temperate cold 1850- 2200 |

cold 2200-2663 |

|

Gravity |

falling, rolling, bouncing, sliding |

rockfall talus |

+ |

++ |

+++ |

+++ |

? |

|

Snow |

snow avalanching slow-moving snow sliding on snow surface |

avalanche talus |

- - |

+ - |

++ no information ++ |

+++ ++ |

++ ++ |

|

Snow and water Snow meltwater Rain storm

water |

slush avalanching ephemeral stream flow rainwash, debris flow |

alluvial talus |

- + + |

- + + |

++ ++ +++ |

+ +++ + |

- + + |

|

Interstitial ice |

internally induced mass movement of debris, creep |

rock glaciers |

|

|

- |

- |

|

|

Freeze-thaw changes |

creep frost creep, sliding |

block slope debros- mantled slope |

- + |

- ++ |

++ +++ |

+ +++ |

+ ++ |

|

|

|

Activity index: |

4 |

7 |

19 |

17 |

9 |

|

Process: - inactive, + weak, ++ strong, +++ very strong |

|||||||

These data indicate that the greatest threats to the geoecological system of the Tatras are posed to the interior of the mountains in the area above the treeline. The threats decrease towards the highest summits of the Tatras as well as towards the foot of the mountains. Increased anthropogenic pollution and the acidification of precipitation (Kot 1992) weaken the stability of Tatra ecosystems and may lead to faster degradation of the geoecological system in the near future.

REFERENCES

Cebulak E., 1983. Maximum Daily Rainfalls in the Tatra Mountains and Podhale Basin. Zesz. Nuk. UJ, Prace geogr. 57, 337-343.

Hess, M., 1965. Pietra Klimatyczne w Polskich Karpatach Zachodnich. Zesz. Nauk. UJ, Prace geogr. 11.267 p.

Janacik, P. 1971. Niektore poznatky z inventarizacneho vyskumu v chranenej krajinej oblasti Mala Fatra. Geogr. casop. 23: 2, 186-191.

Kot., M., 1992. Recent Changes of Surface Waters Chemistry in the Granitic Part of the Tatra National Park - Poland. Acid Rain Research report No. 19/1992. Norwegian Institute for Water Research NIVA, Oslo.

Kotarba A., 1976. Wspolczesne modelowanie weglanowych stokow wysokogorskich. Prace geogr. IGiPZ PAN, 120, 128 p.

Kotarba, A., 1989. On the Age of Debris Flows in the Tatra Mountains. Studia Geomorph. Carpatho-Balcanica 23, 139-152.

Kotarba A., Kaszowski L., Krzemien K., 1987. High-Mountain Denudational System of the Polish Tatra Mountains. Geogr. Studia Special Issue 3, Inst. Geogr. and Spatial Org. PAS, 106 p.

Kotarba A., Stromguist L., 1984. Transport, Sorting and Deposition Processes of Alpine Debris Slope Deposits in the Polish Tatra Mountains. Geogr. Annaler 66A, 4, 285-294.

Midriak R., 1984. Debris Flows and their Occurrence in the Czechoslovak Carpathians, Studia Geomorph. Carpatho-Balcanica 18, 135-149.

Nemcok A., 1982. Zosuvy v Slovenskych Karpatoch, VEDA, Bratislava.

Niedzwiedz T., 1992. Climate of the Tatra Mountains. Mountain Research and Development 12: 2, 131-146.

Pawlowska S., 1962. Plant World of the Tatras. Tatrzanski Park Narodowy, Krakow, 187-239. (in Polish).

Troll C., 1972. Geoecology and World-Wide Differentiation of High-Mountain Ecosystems. In: Geoecology of the High Mountain Regions of Eurasia. Proc. Symp. IGU Commission of High Altitude Geoecology, November 1969. Mainz. 1-16

VYCHODNE KARPATY/EAST CARPATHIAN BIOSPHERE RESERVE

Zuzana Guziova

Slovak Ministry of the Environment

INTRODUCTION

Situated in eastern Slovakia at the junction of the boundaries of Slovakia, Poland, and Ukraine, the Vychodne Karpaty/East Carpathians Biosphere Reserve is part of the tri-national Eastern Carpathians Biosphere Reserve. The area, being part of the Eastern Carpathians, coincides ecologically with the important transition between the Western and Eastern Carpathian ecosystems. This unique geographical position distinguishes the area in Slovakia, which is mostly within the Western Carpathian ecosystems.

Although the area only became a Biosphere Reserve (BR) in 1992, nature conservation dates back to 1906, when the Stuzica reserve was founded near the current border with Poland and Ukraine. Between that time and 1977, several other nature reserves were established, primarily to protect the well-preserved fragments of Eastern Carpathian virgin forests. More complete protection was granted to the area in 1977 when it became a Protected Landscape Area (PLA) of 96,910 ha under the national Nature Conservation Law.

The Biosphere Reserve coincides with the eastern part of the PLA and covers 40,601 ha. In accordance with the Biosphere Reserve concept, the area is further divided into three zones. Each zone falls under a different management regime that corresponds with the natural values of the zones. The core area, covering 2,643 ha, has seven separate parts which represent the best preserved natural ecosystems of beech and fir-and-beech forests, as well as of mountain meadows. The buffer zone of 14,373 ha comprises mostly forest land where stands generally have appropriate species composition, but where spatial and age structure reflect inappropriate management practices in the past. The second buffer zone of 23,585 ha is the largest zone. It differs from the others in having agricultural and forest land, which is used intensively, as well as permanently settled villages.

MANAGEMENT

The Biosphere Reserve is managed by the Administration of the Eastern Carpathians PLA, which is based in Humennne. Under the supervision of the Director, specialists coordinate the management of natural resources within the territory. They help prepare silvicultural and agricultural management plans for enterprises active in the territory of the reserve. The Administration also proposes new Nature Reserves, Protected Sites, and gene pool plots on the basis of scientific recommendations. For rare and endangered plant and animal species, the Administration prepares specific conservation strategies based on the knowledge of population biology. Conservation volunteers from several local NGOs assist the Administration with necessary conservation measures, such as mowing mountain meadows to minimize both direct and indirect risks to species and their biotopes.

The state environmental authorities have overall jurisdiction in the activities and management of the Eastern Carpathians PLA/BR. They verify and provide legal support for the scientific recommendations and proposals submitted by the Administration.

VALUABLE NATURAL FEATURES

The bedrock of the Eastern Carpathian BR is formed almost entirely from flysch rocks of the Dukla Unit of the Upper Cretaceous period and Palaeocene. Sandstone and shale create a complex of strata more than 5,000 m deep. Most of the slopes of the area are covered by deluvial clay and clay-sand loams and talus deposits.

The region has typical smooth flysch relief. The eastern part of the Reserve is in the Bukovske Vrchy Hills. The border ridge with Poland, the highest point of the Reserve, dominates the landscape at altitudes between 797 and 1,208 m. From the main east-west ridge, several smaller mountain ridges stretch southward (separated by the valleys of the Ruske, Runina, Nova Sedlica, and Ulic rivers). The lowest point of the Biosphere Reserve, at 200 m, is in the Ulic Valley, where the Ulicka Riverflows out of Slovakia. The western part of the BR is within the Laborecke Highlands at 600 to 800 m. Their relief reflects their relatively late development and the resistance and structure of their bedrock.

Cambisols and luvisols on flysch sandstone are dominant in the Eastern Carpathians BR. Below 700 m, they are base saturated, while at higher elevations, they are unsaturated and loamy to clay-loamy. Brown and illimeric soils prevail on the agricultural land at lower altitudes.

Since the flysch rocks weather rapidly, and erosion, especially by water, endangers the soils. The mean potential soil loss in the BR is 32.7 m3 per hectare per year. Landslides are common, particularly on slopes with clay bedrock. The weathering products of flysh bedrock tend to swell in wet conditions and subsequently slide.

The Polish border ridge is the European watershed between the Baltic and Black Seas. The Slovak section of the Eastern Carpathians BR is drained by the fan-shaped Ulicka, Ublianka Zbojsky Potok, Cirocha, and Udava basins, whose streams feed into the Bodrog river. The region has very low accumulation capacity despite the abundance of woodland. The Starina reservoir was constructed on the Cirocha river in 1987 to accumulate and permit the use of surface waters. The reservoir has a volume of 60 mil m3 and supplies drinking water to the largest towns of Eastern Slovakia.

The climate reflects the diversity of the relief. Three zones of the Slovak climatic classification can be recognized. The warm zone, with a mean annual temperature of 7 to 8 degrees celsius and mean annual precipitation of 800 mm, is found in the lowest parts of the Cirocha and Ublianka Valleys. The moderately warm zone extends from 400 to 800 m and has a mean annual temperature of 5 degrees celsius and a mean annual precipitation of 900 mm. The highest parts of the region are in the cold zone and have a mean annual temperature of 4 to 5 degrees celsius and a mean annual precipitation above 1000 mm. Highest temperatures usually occur in July, when the maximum mean temperatures range from 20.2 to 24.2 degrees celsius. The coldest month is January, when minimum temperatures fall between -8.6 and -8.2 degrees celsius.

The flora of the Eastern Carpathians Biosphere Reserve is species-rich and biogeographically outstanding. The Bukovske Vrchy Hills form the botanical frontier between the Eastern and Western Carpathians; several Eastern Carpathian endemics reach their western limits in the BR. Other species such as the flax (Linum trigynum) and traveller's joy (Clematis vitalba) reach their northern limits here. Other notable species are medium nipplewort (Lapsana intermedia) and Hacquetia epipactis from the northwest. A detailed inventory of vascular plants has identified over 1,000 species in the Slovak section of the Biosphere Reserve. The known occurrence of 800 species of fungi, more than 300 bryophytes, and more than 100 lichens further illustrates the floristic wealth of the reserve.

Forests are the most common type of vegetation, covering almost 80 percent of the area. The meaning of the name Bukovske Vrchy—the Beech Hills—reflects the dominance of the beech (Fagus sylvatica) within the stands. Other species enrich the composition of the Biosphere Reserve forests based on their ecological tolerance of soil and weather conditions. Accordingly, the lowest parts of the reserve include oaks (Quercus robur, Quercus petraea) and hornbeam (Carpinus betulus ) along with limes (Tilia platyphylla, T. cordata) and maples (Acer platanoides and A. campestre.) Fir (Abies alba) occurs in higher and wetter locations. Valuable deciduous trees, such as Scotch elm (Ulmus montana), ash (Fraxinus excelsior) and sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus ), grow in sites with more humus on talus. Maple-beech forests at the highest elevations (between 1,000 and 1,190 m) are affected by negative ridge phenomena.

Non-forest communities are mostly secondary and arose due to cattle grazing. The most significant are ''poloninas," or grasslands at the timberline, which are species-rich and representative formations of the Eastern Carpathian mountains.

Grasses and rushes such as Nardus stricta, Deschampsia caespitosa, and Luzula luzuloides distinguish the poloninas, but they also include species recognized as Dacian migroelement (Campanula abietina, Aconitum lasiocarpum, Dianthus compactus). Since grazing has ended on the poloninas, the expansion of Calamagrostis arundinacea has lessened the richness of species. This loss of human-induced biodiversity is a specific management problem of the Biosphere Reserve.

Subdominant Anthoxantum odoratum and Agrostis tenuis characterize the meadows and pastures of low and middle elevations respectively. Non-forest communities are also represented by specific vegetation of wet meadows and springs which is of great nature conservation importance.

The zoological value of the region is also high. A unique range of animal species and communities reflects the geographical location at the junction of the Eastern and Western Carpathians. So far, about 1,400 animal species have been found, including more than 1,100 species of invertebrates. Invertebrates include representatives of almost all the principal systematic groups. Among invertebrates, the class of insects, with about 950 species, is the best represented. Populations of vertebrates were influenced in later years by the degree of disturbance of particular ecosystems. Of special note is the presence of large predators, including lynx and bear. Small carnivores such as wild cat and badger are abundant. Red and roe deer populations are too high and create specific management problems with respect to the regeneration of some tree species, especially fir. In recent year, the rare ungulates Bison bonasus and Alces alces have occasionally been observed. Several species occurring in the Biosphere Reserve can be traced to early stages of the development of the Carpathian fauna. For example, Dicellophilus carniolensis is a Tertiary relic, while Duvalius subterraneus, Sicista betulina, Picoides tridactylus, Turdus torquatus, and Sorex alpinus are glacial relics.

There are many endemics of the West Carpathians: Chromatoiulus sylvaticus, Agardia bielzii, Helicigona faustina, Trechus pulpani, Nebria fuscipes , and triturus montandoni. However, the East Carpathian endemics Leptoilus byconyensis stuzicensis, Polydesmus polonicus, Carpathica calophana, Stenus obscuripes and Deltomerus carpathicus are also present. Several species previously unknown to science have been discovered in the territory, such as Tachydromia carpathica and Lioides nitida sedlicensis.

The botanical and zoological importance of the Biosphere Reserve is further emphasized by the fact that 23 of its vascular plants are protected by law. Another 22 are seriously endangered, 33 very endangered, 52 endangered, and 86 rare in Slovakia. Similarly, a total of 27 species of invertebrate and 148 vertebrates found in the region are protected by law. The peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus ) is even included in the IUCN Red Data Book. The most valuable biotopes or best preserved ecosystems have been recognized as Nature Reserves or Protected Sites with strict protection regimes. These cover 1,384 ha or 3.4 percent of the area.

PEOPLE AND AREA

The region of the Eastern Carpathian Biosphere Reserve was settled in the Early Stone Age. The next wave of colonization occurred in the late 14th century when Ruthenian pastoral-agrarian people arrived. This was the beginning of the Wallachian colonization, a period which lasted until the 17th century. The Wallachian colonization was responsible for the essential landscape features of the region, including the basic settlement pattern and the botanical heritage of the poloninas.

Currently, more than 3,000 (3,721 in 1991) permanent inhabitants live in 10 villages in the eastern part of the area. Seven villages in the western part were evacuated during the construction of the Starina reservoir. The economic and cultural center of the region is the town of Ulic (1,200 inhabitants).

Most of the local people work in forestry. Although more than half of the forests are privately owned, they are all still managed by state enterprises. Of the total area of forest, some 23,334 ha serve chiefly for timber production, while 1,178 ha, mostly on steep slopes, are designated for protection against soil erosion. The remaining 7,391 ha include areas such as the fragments of the virgin forests, which are most important for nature conservation. These last "special use forests" also include forests in the sanitary zone around the Starina reservoir.

Agricultural land covers 6,480 ha. The climate dictates that agricultural activities are based primarily on the production of crops for fodder. Wheat, rye, barley, and oats are also cultivated, and the traditional crop is buckwheat.

The cultivation of private village plots over many generations has resulted in a mosaic of little fields and meadows that give the landscape a unique pattern. Agricultural enterprises remain active in the area but are in decline as a result of the re-privatization process in Slovakia.

Tradition and the production of crops dominantly for fodder were primary reasons that farmers bred cattle and sheep on the Biosphere Reserve. The Starina Reservoir and its sanitary zone have limited agricultural activities. Large pastures are now abandoned, as they become overgrown, biodiversity decreases.

Tourism and sports in the territory have been limited, but could, if developed, play an important role as a future source of income for local inhabitants.

The Eastern Carpathian Biosphere Reserve has not only preserved fragments of natural ecosystems, but also the biodiversity resulting from human activities. It therefore deserves to be a part of the international network of Biosphere Reserves and, as such, should be protected for future generations. Its future conservation and development should be parallel to the protection and development of the entire area of the tri-national Polish-Slovak-Ukraine reserve. This approach emphasizes the global importance of the region.

REFERENCES

Guziova, Z. and Bural, M. 1994. Vychodne Karpaty/East Carpathians Biosphere Reserve. In: Biosphere Reserve on the Crossroads of Central Europe, EMPORA Publishing house, Prague.

Guziova, Z. et al. 1992. Proposal for Poloniny National Park. Manuscript.

Guziova, Z. et al. 1992. Nomination of the Eastern Carpathians Biosphere Reserve. Manuscript.

Voloscuk, I. et al. 1988. Vychodne Karpaty- chranena krajinna oblast. Priroda, Bratislava.

BIESZCZADY NATIONAL PARK

Zbigniew Niewiadomski

Bieszczady National Park

The Bieszczady National Park covers 27,064 ha in the south-east corner of Poland, where the borders of Poland, Ukraine and Slovakia meet. The National Board for the National Parks of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, Natural Resources, and Forestry administers Bieszczady National Park, which was created on August 4, 1973.

The present borders of the Park should not be considered final. Many believe that the Park should be expanded to include the entire Upper San Valley and some forest complexes located to the north and west of the present boundary. Factors which support the enlargement of the Park include a sparse population in the area (low by Polish standards at 4 people per km2), the low usage of the land, the unprofitability of the forest-agriculture economic model in Bieszczady, and the wide state ownership of the forested and post-agricultural areas adjoining the Park. Consequently, the Park desires a final area of about 41,000 ha.

The development of the Bieszczady region is expected to include the gradual professional re-orientation of the population towards the tourism industry. Tourist villages should grow in the immediate vicinity of the Park and extensive areas of the San Valley should be devoted to hiking, horseback riding, and cycling, as well as to fishing, nature photography, and ecological education. The protection of the natural resources of the Bieszczady may thus gain allies in the local population, who will earn incomes by servicing the tourists visiting the National Park and the Eastern Carpathians International Biosphere Reserve (IBR).

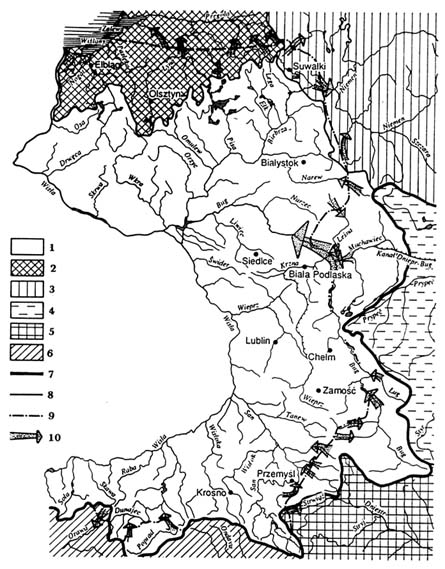

It was initially proposed 20 years ago that an internationally protected area be established in Bieszczady, but the political situation at the time did not favor implementation. In 1990, however, at the UNESCO MAB Conference in Kiev, the Polish party proposed the creation of a Biosphere Reserve in the Eastern Carpathians under the UNESCO Man and Biosphere Program. The Ministers of Environmental Protection of the three countries accepted the proposal and signed an agreement in Ustrzyki Dolne in 1991. Preparations to apply the project began immediately. The proposal gained official backing from the UNESCO MAB Headquarters in 1992 for the Polish and Slovak parts and in 1993 for the Ukrainian part.

The total area of the Eastern Carpathians IBR is about 164,000 ha, of which 66 percent (108,725 ha) is in Poland, 24.7 percent (40,601 ha) is in Slovakia, and

8.9 percent (approximately 14,600 ha) is in Ukraine. The Polish section includes the National Park, as well as the San Valley and Cisna-Wetlina Landscape Parks, which were created in 1992 and which cover 36,635 and 46,025 ha respectively. The Slovak section includes a part of the "Vychodne Karpaty" CHKO (Area of Protected Landscape), which to be upgraded to the status of a national park under the name "Poloniny" National Park. On the Ukrainian side, the IBR currently includes the Stuzyca Nature Reserve. It is also possible that the Ukrainian sector could implement the planned Nadsanie Landscape Park, a move that would allow for extensive protection of the drainage basin of the Upper San River on both sides of the border.

The concept of the Biosphere Reserve is founded upon the idea of a zonal system of protected land. In this system, the most naturally valuable core zone is subject to strict protection, while the surrounding buffer zone is partially protected. In the outermost transition zone, attempts are made to minimize the negative impacts of human activities. In Poland, the core and buffer zones are both within the boundaries of Biesczadzki National Park, while the surrounding transition zone is administered separately.

The Eastern Carpathians IBR was created to promote cooperation in the protection and rational use of the natural resources of the Bieszczady Mountains, in scientific research, and in monitoring the environment and ecological education. In addition, the IBR seeks to strengthen the links between the people of the Eastern Carpathians through cooperation and the joint protection of cultural heritage. The Carpathian forests play a significant role in water protection, and hence in the agriculture and industry of central European countries. The IBR is also an important element within the officially recognized European region of the Eastern Carpathians, which was established by Poland, Slovakia, Ukraine, and Hungary.

Poland's Bieszczadzki National Park is dominated (84 percent cover) by forests. Beech forest is the major type, constituting 80 percent, with a mixture of fir and sycamore. The natural, and sometimes even primordial, character of these stands is unique in Europe. Also unique, at least from the Polish point of view, are the floristically-rich alpine pastures and meadows which the Park protects. The area's raised bogs are also of interest. The geographical location of the Park ensures the occurrence of species from both the Western and Eastern Carpathians, resulting in the wealth of the flora. In Poland, 57 rare species of plants are protected, with 12 of these being classified as endangered in the country as a whole. The fauna is also of interest; the Park preserves all of the original mammalian predators, including the brown bear (Ursus arctos), wolf (Canis lupus), lynx (Felis lynx ), wild cat (F. silvestris), and otter (Lutra lutra). The majority of the original group of large herbivores can also be found in the Park: European bison (Bison bonasus) and red deer (Cervus elaphus). The red deer, in its Carpathian form, is the most magnificent to be found in Europe. Rare birds are also well represented in the Park, with notable species including golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), lesser spotted and spotted eagles (A. pomarina, A, clanga), short-toed eagle (Circaetus gallicus), eagle owl (Bubo bubo), and Ural owl (Strix uralensis).

Bieszczady National Park is divided into zones that are under strict or partial protection. Strict protection covers 18,536 ha, which, as of December 1991, represents 44 percent of the total area of this type found within all Poland's National Parks. This attests to the unique value of the Park's natural resources on the Polish scale. The areas under strict protection fall within six legally recognized Strict Nature Reserves. All human activities are excluded from these areas, with the goal of observing natural ecological processes and maintaining nature without disturbing it through protective measures. Activities are thus restricted to scientific research that will not cause changes in nature, and sightseeing is only allowed from marked tourist paths and nature trails.

Strict Nature Reserves located outside the Park, in the transition zone of the Biosphere Reserve, should enjoy the same status as the core zone. However, this would require their surroundings to be secured with a buffer zone.

Zones under partial protection, which cover 8,528 ha of the Park, act as buffer zones for the areas under strict protection. These buffer zones protect against the negative effects of human activities, particularly those resulting from traffic along communication routes and the anthropogenic influence of inhabited areas. Human intervention, tourism, and recreation are permitted in partially protected areas. Scientists also conduct research and collect plant and animal samples in these zones. However, the fundamental activity in the partially protected zones is the active protection of natural resources with the goal of returning the environment as closely as possible to its natural state. This is achieved through the restructuring of forest stands, regulation of animal populations, intervention in the species composition of plant communities, the nursing and cultivation of desirable elements, and the elimination of elements alien to the native biocoenoses. The Protective Plan for Bieszczadzki National Park, which will facilitate such protective actions, is now being drawn up. This Plan is expected to provide model solutions for other National Parks in Poland.

Attempts to use the mountain valleys for large-scale agriculture considerably damaged the Bieszczady area. Extensive areas in the San Valley and in Wolosate were cleared and drained in order to "recultivate" the land for cattle breeding and other agricultural industries. However, drainage reduced the land's retentiveness and often partially destroyed the raised bogs unique to the area. Agricultural activity also damaged the alluvial ecosystems and belts of trees along watercourses, which represent natural ecological corridors for flora and fauna. The inclusion of these areas within the National Park stopped such environmentally unfriendly processes, and work is now beginning to restore the level of retentiveness and the ecosystems which have been destroyed.

In addition to increasing economic utilization, the development of the settlements and roads (especially the Bieszczady "ringroad") crossing the most naturally valuable areas enabled motorized tourism to invade Bieszczady. The number of tourists to Bieszczady rose from only about 1500 in 1953 to around 3 million visitors per year just twenty years later (a small National Park was established in 1973). However, the trend of tourism is now changing again due to

society's reduced affluence. Specialized mountain tourism, which is less harmful to the Park, is taking the place of mass tourism, and the number of tourists visiting the Park annually has fallen to around 350,000. The Park intends to stimulate the development of tourist villages in the surrounding area. This strategy promotes the use of the Lake Solinski area for vacationing and recreation as well as the establishment of camping sites along the Park boundaries. These tourist villages will create a barrier system which will restrain and dissipate the influence exerted by tourists upon the areas most valuable from the point of view of nature conservation.

Ecotourism, or the linkage of walking or hiking with ecological education and wildlife photography, is continuing to grow in popularity. The Park intends to develop ski racing and mountain tourism by foot and horseback. Plans also include a network of ecological education points around the Park and IBR. The Park is working on a camp ground in Wetlina with the goal of reducing the number of stays within the Park itself. An unfavorable factor at present is the lack of a visitor center linked to the regional tourist information network.

In addition to all this, the Park is working with the Polish Tourist and Country lovers Society (PTTK) to conserve the network of marked tourist trails and to install shelters along them. Litter left by tourists must also be removed. A network of parking lots furnished with rest rooms will be built, and traffic and parking will gradually be limited in order to reduce the negative effects of traffic along the section of the Bieszczady ring road which passes through the Park. This project is being financed by the European Union.

Many tourists enjoy the research farm for East Carpathian ponies in the Park, and when they pass through Ustrzyki Dolne, they discover that the Park's Natural History Museum is one of the most attractive in any of the Polish National Parks. A further tourist attraction is Poland's oldest narrow-gauge mountain railway, which began operating almost a century ago. If Poland, Slovakia, and Ukraine sign an agreement on a tourist convention for the Eastern Carpathians Biosphere Reserve, the Park would attract international interest. In fact, potential border crossing points within the IBR have already been selected, but will be limited to tourists on foot, horseback, or bicycle. Encouraging motorized traffic would hinder the nature conservation in this unique European protected area.

The Park's main goal of protecting nature would be an impossible task without the cooperation of economically or socially active entities in the area. Such groups include the State Forests and the local authorities, as well as school children, local inhabitants, ecological and tourist organizations, and admirers of the Bieszczady Mountains throughout Poland. In turn, it is critical that the Park's representatives help design economic plans and the spatial management of the Bieszczady region. Volunteer groups also assist the Park constructively. Examples of valuable volunteer work include the "Clean Mountains" campaign run by young students and the activities of the Mounted Nature Conservation Guard in Przemysl. Volunteers have also cooperated to conserve and renovate cemeteries, an important element of the region's heritage.

The Park has taken steps to create a network of ecological education points for tourists, local people, and young students. As a sanctuary for nature in the Bieszczady Mountains, the Park may thus become a major center in Poland for the promotion of ecological knowledge and nature conservation. Brochures, information booklets, and guides also serve to advance popular knowledge about nature. The Scientific Research Institute of the Eastern Carpathians International Biosphere Reserve, created in 1993 in Wolosaty, facilitates scientific research within the Reserve and helps organize conferences. An IBR cooperation center is also to be established nearby in 1995. In turn, one of four International Ecological Institutes to be created in Poland is planned for Ustrzyki Dolne.