BIALOWIEZA PRIMEVAL FOREST: HABITAT AND WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT

Henryk Okarma and Wojciech Jedrzejewski

Mammal Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences

Boguslawa Jedrzejewska

Workshops for Ecology and Protection of the Natural Environment

INTRODUCTION

Bialowieza Primeval Forest (1451 km2) is one of the best preserved forest ecosystems in lowland temperate Europe (Falinski 1986). Due to historical changes, the forest complex has been divided between two countries, each of which follow different forest and wildlife management practices.

The aim of this paper is to describe the effects of these practices over the past 50 years on forest structure, ungulate community, and large predators. A further aim is to define the main threats to this unique forest and suggest measures to improve its current status.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Bialowieza Forest was a royal hunting ground of Polish kings and was strictly protected until the end of the 18th century. After Poland lost its independence in the 19th century, the forest became the czars' game reserve. Several measures were undertaken to promote ungulates, e.g., introduction of alien species (fallow deer, Siberian roe deer), supplementary winter feeding, and persecution of large carnivores. During the two world wars of the 20th century, most game species were decimated and some eradicated. After World War II, the whole forest complex was divided between the Soviet Union (874 km2) and Poland (577 km2), which resulted in two totally different methods of forest and wildlife management. Since 1981, the Polish and Belarusian parts of the forest have been separated from each other by a double wire fence built by the Soviets.

Most of the Polish part of the forest (530 km2) is a commercial forest (exploited for timber and subject to game management). Only a small part of it (47 km2) has been strictly protected since 1921 as the Bialowieza National Park (BNP),

where neither timber exploitation nor hunting is allowed (see map p. 111). It has been a UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve since 1977 and a World Heritage Site since 1979. The entire Belarusian part of the forest has State National Park status, under which several management measures are used. The forests are not exploited for timber, and only dead trees are removed. Ungulates are favored and large carnivores persecuted. In 1993, the entire Belarusian part of the forest was declared a biosphere reserve, with three protection zones (totally protected area, buffer zone, and ecological agriculture zone).

SOURCES OF DATA

Data on species structure and age of tree stands for the Bialowieza Forest were obtained from three sources. For the BNP, data came from the headquarters of Bialowieza National Park (1989 inventory), and for the exploited part from the office of the Bialowieza Forest Administration (1970 inventory). For the Belarusian part, data were provided by the Forestry Department of Belovezhskaya Pushcha State National Park (courtesy of A. Bunevich).

Information on species structure of the ungulate community and density of ungulates also came from three sources. Data for Bialowieza National Park came from a research project on predator community conducted by the Mammal Research Institute (Jedrzejewski et al. 1989, Jedrzejewski et al. 1992), in which snowtracking and driving censuses were used (Jedrzejewska et al. 1994). Data from the exploited part of the forest came from game inventories conducted by game wardens of the Bialowieza Forest Administration, where snowtracking and driving censuses were also used (courtesy of L. Miekowski). For the Belarusian part, the ungulate density data were obtained from the Game Management Department of the Belovezhskaya Pushcha State National Park (courtesy of A. Bunevich). Snowtracking was used for game inventory.

A detailed description of the methodology of forest and game inventory was provided by Jedrzejewska et al. (1994).

FOREST STRUCTURE

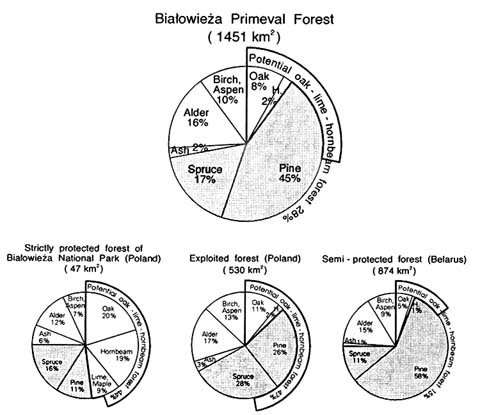

The major part of the tree stands in the pristine forest of BNP (72.5%) is dominated by deciduous species: oak (Quercus robur), hornbeam (Carpinus betulus), alder (Alnus glutinosa), lime (Tilia cordata), and Norway maple (Acer platanoides) (Fig. 1). In spite of the fact that a potential oak-lime-hornbeam forest should have formed in the exploited part of the forest, coniferous stands (54%) with spruce (Picea abies) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) predominate in nearly 50% of the tree stand. These species have been used for replanting, as they are economically valuable timber species. The practice of clear-cutting has promoted birch (Betula verrucosa and B. pubescens ) and aspen (Populus tremula) (13%).

Other deciduous tree species like Norway maple and lime have nearly disappeared as a result of management practices (Fig. 1).

In the Belarusian part of the forest, the natural dominant tree stands are mixed coniferous (mainly Scots pine) with a high proportion of oak. The potential area covered by oak-lime-hornbeam forest is smaller than that in the Polish part of the forest (15%), and the actual area where such tree stands predominate is less than half the size (31%). This decrease was a result of heavy timber exploitation in the 1920s and 1930s. In both the Belarusian part and in the Bialowieza National Park there is the same proportion of tree stands (25%) in which alder, aspen, birch, and ash predominate (Fig. 1).

AGE AND EXPLOITATION OF THE FOREST

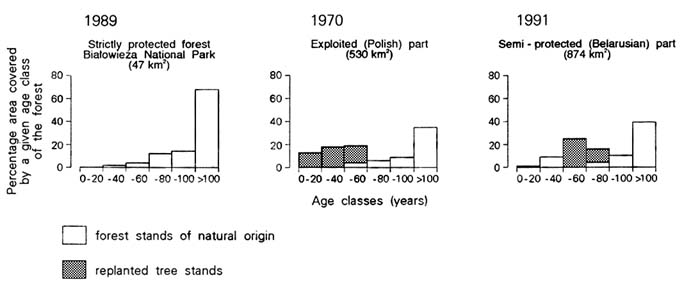

The age structure of the tree stands differs in the various areas. Nearly the entire forest of BNP consists of mature stands of natural origin. Stands over 100 years old comprise 67.4% of all tree stands, while young stands less than 40 years old represent only 2.4%. The average age of tree stands is 130 years (Fig. 2).

The majority of the exploited forests are of secondary origin (planted). In 1970, the oldest age classes (over 100 years) constituted 30%, and the youngest (less than 40 years) included 27% of all stands. The average age of tree stands was 72 years (Jedrzejewska et al. 1994). Since data on the age of the exploited forest came from 1970, we can expect that the current average age of tree stands is even lower. However, even comparing data of 20 years' difference for these two parks (Fig. 2), it is evident that management practices have had disastrous effects on the forest and have led to the total degeneration of the natural character of the Bialowieza Forest.

In the protected forest in the Belarusian part, the effect of the heavy cutting of the forest in the 1920s and 1930s is visible in the age structure (Fig. 2). A considerable number of tree stands consist of coniferous replanted tree stands (70 years old on average). Only in younger age classes has the lack of timber exploitation begun to lead to a restoration of the natural age structure of the forest. There is still a large percentage of tree stands older than 100 years, and as a result the average age of all tree stands is 97 years, more than in the Polish exploited part (Fig. 2).

There is an essential difference between the exploitation of the forest in the Polish and Belarusian parts. In the latter, only selective cutting of dead trees takes place, and there have been no clear-cuts or replantations since 1951. The level of timber exploitation per year (1951-1991) was 0.81.7 m3/ha. In the Polish part, heavy exploitation and large-scale replantation occurs. The level of timber harvest, at 3.04.8 m3/ha., is on average four times higher.

WILDLIFE DENSITY AND MANAGEMENT

Bialowieza Forest harbors a nearly pristine community of ungulates: European bison (Bison bonasus), moose (Alces alces), red deer (Cervus elaphus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), and wild boar (Sus scrofa ) (Jedrzejewski et al. 1992). They coexist with two species of large predators: wolf (Canis lupus) and lynx (Lynx lynx), which are at the westernmost limit of their range in lowland Europe (Okarma 1990, 1993).

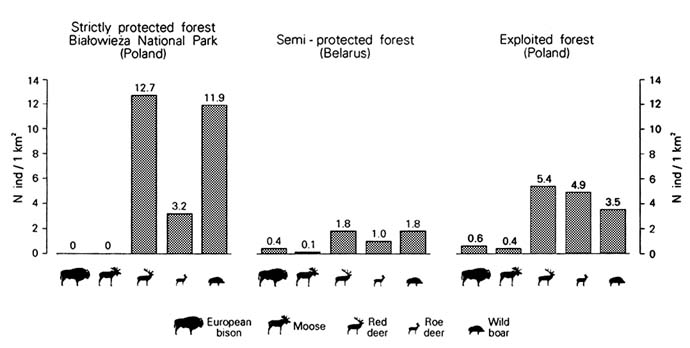

There are major differences in ungulate density in the Polish parts of the forest. Within the Bialowieza National Park, ungulate density is very high (Fig. 3). Two species predominate: red deer (12.7 ind/km2) and wild boar (11.9 ind/km2). In the exploited forest the density of red deer is two times lower, and wild boar three times lower, while roe deer were more numerous than in the National Park (Fig. 3). These differences in ungulate density could be explained by different species and age structure of the forest (Jedrzejewska et al. 1994). It was found that the total biomass of ungulates-herbivores (European bison, moose, red deer, and roe deer) per unit area was significantly correlated with the percentage of the area covered with tree stands dominated by deciduous trees, while the biomass of ungulates-omnivores (wild boar) correlated with the percentage of the area covered with old tree stands (over 80 years) where production of seeds (primarily acorns) is highest (the average yearly crop was 16.4 tons/km2 in the Bialowieza Forest). This is why many more ungulates inhabit old-growth deciduous forests in Bialowieza National Park than coniferous-dominated younger forests in the exploited part.

In the Belarusian part of the forest, where coniferous stands predominate, the density of ungulates is much lower (Fig. 3). Red deer and wild boar are dominant species there, but their density is on average six times lower than in Bialowieza National Park.

In the Polish part, all ungulates except European bison are hunted under an annual harvest plan. European bison is a protected species and is excluded from regular game management; its population size is kept stable (recently at a level of about 230-250 individuals) by the National Park authorities by culling several individuals per year (primarily sick and injured ones). Recently there has been a lot of controversy concerning bison management strategy. Foresters have claimed that bison density is too high and that this species causes heavy damage to the forest. Despite the fact that most of this damage is probably caused by red deer (Pucek 1993), the forest authorities still required the number of bison to be reduced.

Until 1990, the harvest of ungulates was on a moderate level in comparison to estimated population size (Table 1). Relatively more wild boar were harvested, but this species also exhibits the fastest potential reproduction rate. During the last two years, the harvest increased drastically (for wild boar up to 50% of the estimated population size). Such a management tendency clearly reflects the attitude of forest authorities toward ungulates (the case of the bison was already mentioned), which they also believe cause excessive damage to replantations.

TABLE 1 Harvest of Ungulates from the Polish and the Belarusian Part of the Bialowieza Forest in 1988-92. Estimated population Size N (average yearly values), harvest (average yearly values), a

|

|

1988-90 |

1991-92 |

||||

|

|

N1 |

Harvest |

N2 |

Harvest |

||

|

|

|

N |

% |

|

N |

% |

|

POLAND |

||||||

|

Red deer |

2000 |

289 |

14% |

286 |

700 |

25% |

|

Roe deer |

1900 |

230 |

12% |

2590 |

540 |

21% |

|

Wild boar |

1200 |

340 |

28% |

1850 |

930 |

50% |

|

BELARUS3 (1988-92) |

||||||

|

Red deer |

1550 |

156 |

10% |

|

|

|

|

Roe deer |

900 |

54 |

6% |

|

|

|

|

Wild boar |

1590 |

350 |

22% |

|

|

|

|

1 Since officially reported numbers of ungulates were heavily underestimated (only snowtracking over a grid of 100 ha), estimated numbers of ungulates were taken as to be somewhat lower than an accurate 1991 estimates. Number of ungulates estimated on the basis of driving censuses conducted in winter 1991. 2 Number of ungulates estimated on the basis of snowtracking censuses. These censuses were conducted over a 3 grid of 25 ha, which gives an estimate of ungulate density similar to the driving census (Z. Pucek, unpubl. data). |

||||||

In the Belarusian part of the forest, the bison is also a protected species (about 300 individuals). Only sick individuals are culled, and there is very limited hunting by Western hunters. Red deer, roe deer, and wild boar are harvested under an annual harvest plan, and the harvest is at a similar levels as in the 1970s (Table 1). The level of harvest there was comparable to the harvest in the Polish part up to the late 1980s (Table 1).

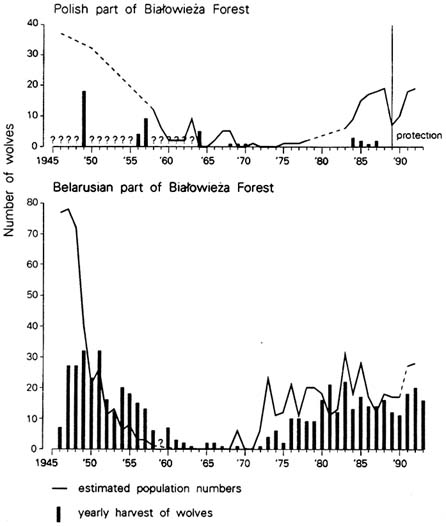

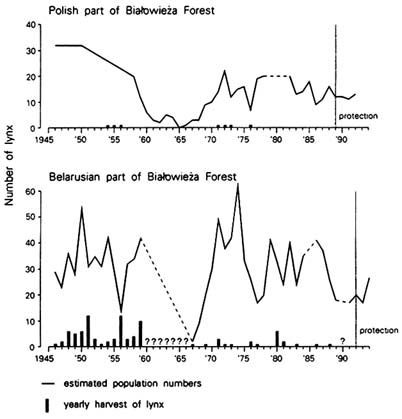

Wolf and lynx were persecuted both in the Soviet Union and in Poland in the 1950s. During this period, more than 30 wolves were reported to have been killed in the entire complex of the forest, most of them in the Belarusian part (Fig. 4). In the 1960s and 1970s, the numbers of these predators decreased considerably, and as a result only a few of them were killed (Fig. 4, 5). In the 1980s and 1990s there was a sharp increase in the numbers of wolves killed. More lynx were also killed (Fig. 5). It is impossible to give an accurate number of wolf and lynx inhabiting the forest, because methods of estimating the population size of these species are

unreliable (Okarma 1989, 1993; Okarma et al. 1992). However, the numbers given (especially the level of harvest) do reflect some population trends.

Since the late 1980s, management of these species has become different in the two parts of Bialowieza Forest (Okarma 1993). In the Polish part, wolf and lynx have been protected since 1989, but in Belarus lynx only became a protected species in 1993 (Sachanka et al. 1993). Wolves are still heavily controlled, with more than 60% of the estimated population being taken (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4 Estimated Population Size and Yearly Harvest of Wolves in the Polish and Belarusian Part of Bialowieza Forest in 1948-93

FIGURE 5 Estimated Population Size and Yearly Harvest of Lynx in the Polish and Belarusian Part of Bialowieza Forest in 1948-93.

CONCLUSIONS

-

The Bialowieza Forest is still relatively well preserved by European standards; however, it has dramatically lost its primeval character due to forest exploitation. Human intervention has also had a severe effect on the system of ungulates and large carnivores.

-

There has been practically no cooperation between the Polish and the Belarusian parts of the forest regarding forest and game management. There is an urgent need for such cooperation, which should include the following:

-

stopping the exploitation of the forest and initiating restoration of the natural character of replanted tree stands;

-

-

unifying game management practices in both parks (comparable methods to be employed for the game number inventory, protection of large carnivores in the Belarusian part, and termination of the excessive killing of ungulates in the Polish part of the forest).

-

European bison should be considered a priority species in the ungulate community of Bialowieza Forest. This species should be protected, with its number kept approximately at the present level. Accordingly, the density of other ungulates should be limited so that their numbers do not exceed the carrying capacity of the forest. Several measures should be taken to achieve a balance between the food requirements of ungulates and the food supply (e.g., restoration of meadows which underwent secondary forest succession in forest clearings and along river valleys) (Pucek 1993).

-

The Bialowieza National Park should be enlarged to include the entire Polish part of the forest (with the three protection zones). The UNESCOMAN requirements for Biosphere Reserves would then be met.

Acknowledgments: We thank K. Zub for preparing the figures.

REFERENCES

Falinski J. B. 1986. Vegetation Dynamics in Temperate Lowland Primeval Forest. Dr W. Junk Publishers, Dordrecht. Geobotany, 8:15-37.

Jedrzejewska B., Okarma H., Jedrzejewski W, Miekowski L. 1994. Effect of Exploitation and Protection on Forest Structure, Ungulate Density, and Wolf Predation in Bialowieza Primeval Forest, Poland. J. Appl. Ecol. [In press]

Jedrzejewski W. Jedrzejewska B., Okarma H., Ruprecht A. L. 1992. Wolf Predation and Snow Cover as Mortality Factors in the Ungulate Community of Bialowieza National Park, Poland. Oecologia (Berl.) 90: 27-36.

Jedrzejewski W., Jedrzejewska B., Szymura A. 1989. Food Niche Overlaps in a Winter Community of Predators in the Bialowieza Primeval Forest. Acta theriol. 34: 487-496.

Jedrzejewski W., Schmidt K., Minkowski L., Jedrzejewska B., Okarma H. 1993. Foraging by Lynx and its Role in Ungulate Mortality: the Local (Bialowieza Forest) and Palaearctic Viewpoints . Acta theriol. 38: 385-403.

Okarma H. 1989. Distribution and Number of Wolves in Poland. Actatheriol. 34: 497-503.

Okarma H. 1990. Status, Distribution and Numbers of Lynx in Poland. Seminar on the Situation, Conservation Needs and Reintroduction of Lynx in Europe. Switzerland, October 1990.

Okarma H. 1992. Following the Lynx. Lowiec Polski 11: 16-17. [In Polish]

Okarma H. 1993. Status and Management of the Wolf in Poland. Biol. Conserv. 66: 153-158.

Okarma H. 1993. Protection and Management of Large Carnivores (Wolf, Lynx) in the Bialowieza Primeval Forest, Poland. Proc. of the Seminar on the Management of Small Populations of Threatened Mammals. Bulgaria, October 1993.

Pucek Z. 1993. European Bison in the Bialowieza Primeval Forest. Echa Lesne 9: 14. [In Polish]

Sachanka B. I., Kurlovich M. M., Malashevich Y. V., Samuel S P. , Khauratovich I. P. (eds.). 1993. Khyrvonaya Kniga Respubliki Belarus. In: Belarusi, Minsk: 35-36.

THE MANAGEMENT OF LARGE MAMMALS IN THE EASTERN CARPATHIANS BIOSPHERE RESERVE

Kajetan Perzanowski, Boguslaw Bobek, W. Frackowiak,

R. Gula, Beata Kabza, and Doreta Merta

Jagiellonian University

INTRODUCTION

Protected areas in Poland are generally rather small, and their management lacks coordination with such surrounding units as state forests and hunting districts (Kabza 1994). Like other protected units in Europe, they are prone to the loss, isolation, and fragmentation of suitable wildlife habitats (Wallis de Vries 1994). Populations of large mammals are particularly difficult to manage due to the considerable home ranges of individuals, and this task becomes even more difficult in the mountains, because of the vertical gradient of habitat conditions (Bobek et al. 1992c).

This paper uses the results of research projects carried out in the Bieszczady Mountains by the Jagiellonian University Department of Wildlife Research to discuss the status of several mammal species in the Eastern Carpathians Biosphere Reserve and to consider the possible implications for management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Four species were surveyed to various extents: red deer (Cervus elaphus ), wolf (Canis lupus), brown bear (Ursus arctos), and otter (Lutra lutra).

The longest and most thorough study involved red deer and considered the following population parameters:

-

sex and age structure (Bobek and Kosobucka 1985, Godawa 1989);

-

recruitment rate (Kadziela 1984);

-

mortality factors, including hunting (Okarma 1984, Perzanowski 1992);

-

spatial distribution (Bobek et al. 1984);

-

physiological factors (Kapral 1984, Bobek et al. 1990a);

-

predator-prey relationships (Bobek et al. 1987, Lesniewicz and Perzanowski 1989, Bobek et al. 1992d); and

-

diet composition, habitat selection, and use (Perzanowski et al. 1986, Pis 1986, Bobek et al. 1992c).

In wolves, studies were conducted on nutritional aspects (diet composition, consumption and digestibility of natural foods, and basic metabolism), the impact on potential prey, and conflicts with man (Okarma 1984, Okarma and Koteja 1987, Lesniewicz and Perzanowski 1989, Bobek et al. 1992d, Bobek et al. 1994, Bobek and Perzanowski 1994).

The study on the brown bear focused on population estimates, composition of the natural diet, and damage to livestock and property (Frackowiak and Gula 1992, Frackowiak 1992, Gula 1992, Bobek and al. 1994, Gula and Frackowiak 1994). The population of otters was studied with regard to seasonal changes in the composition of the diet (Harna 1993).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Analysis and discussion will focus on the following factors considered important for the management of the red deer population: a) population trends and distribution; b) interactions with vegetation; c) habitat selection and use; and d) antler quality.

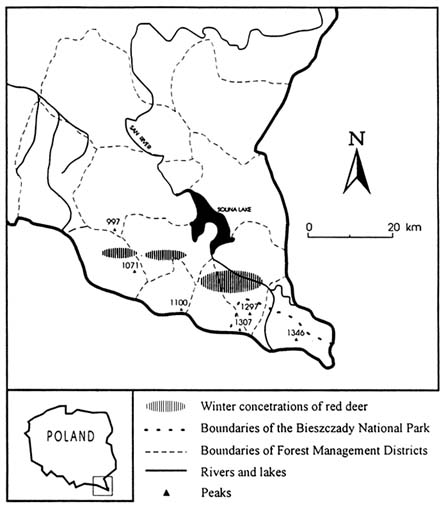

To assess population trends, it is necessary to develop the least intrusive method of population census possible. The proposed method for protected areas, already tested in Bieszczady, is the Langvatn formula, which is based on direct observations and a count of roaring stags (Langvatn 1977, Bobek et al. 1986). Harvest and losses due to predation are undoubtedly the most important mortality factors (Table 1). The spatial distribution of the red deer population in Bieszczady (which has been studied with traditional methods, but soon it is hoped with radiotelemetry) undergoes considerable seasonal changes. Especially important in management are the vertical movements, which begin from wintering areas of high population density and follow the availability of high-quality forage (Fig. 1). This pattern has altered in the last few years as a result of the bankruptcy of former state farms.

Studies on the interactions of the red deer population with vegetation include estimates of the composition of the red deer diet, especially in winter. It has been found that the most important item in that critical season are the evergreen leaves of blackberry (Lankof 1991). This has direct implications for forest management in terms of the appropriate pattern of timber harvest to ensure the maintenance of optimal basal tree area for the regeneration and growth of blackberry (Bobek et al. 1991).

TABLE 1 Average Population Numbers, Harvest and Reported Losses for Five Big Game Species in the Eight Forest Districts of the Bieszczady Mountains (according to State Forest Administration records)

|

Species |

Season |

1989/90 |

1990/91 |

1991/92 |

1992/93 |

1993/94 |

Average numbers estimated after season |

|

Red deer |

H |

810 |

1170 |

2040 |

1422 |

928 |

2800 |

|

|

L |

232 |

241 |

315 |

253 |

294 |

|

|

Roe deer |

H |

69 |

134 |

292 |

370 |

283 |

1800 |

|

|

L |

63 |

128 |

93 |

123 |

122 |

|

|

Wild boar |

H |

171 |

128 |

142 |

44 |

92 |

550 |

|

|

L |

83 |

87 |

52 |

54 |

38 |

|

|

Wolf |

H |

22 |

13 |

17 |

16 |

17 |

130 |

|

|

L |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

|

Lynx |

H |

2 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

60 |

|

|

L |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Habitat changes caused by forest management have a direct influence on the growth of deer bodies and antlers. There is an optimal ratio of habitats providing food and cover for the rate of growth of an individual (Bobek et al. 1991). That proportion may be disturbed easily by the common practice of planting spruce on former meadows and farmlands.

A still largely unrecognized opportunity to improve habitat for deer is to increase the length of certain ecotones, which may potentially offer better quality food than neighboring forest stands (Moranda 1993, Bobek et al. 1992, Bobek and Merta 1994). This may not only stimulate the growth of bodies and antlers, but also may help to reduce browsing pressure on young stands in the forest. This problem is closely connected with the need to develop environmentally-friendly methods of preventing undesirable browsing and bark stripping. Quite promising results have been obtained from experiments with repellents based on egg yolks, which have already been carried out in Baligrod Forest District (Kasprowicz 1992).

Deer antlers may not seem like a very important factor to be considered in deer management in protected areas, but it is impossible to overlook the fact that, according to rough estimates, the annual revenue from hunting licenses in Bieszczady is approximately 2.5 million dollars. At present, game management remains the most profitable element of forest management within the area of the Biosphere Reserve, and the future development of ecotourism is likely to allow the famous antlers of Bieszczady stags to bring even more income to the region. In

FIGURE 1 Winter Concentrations of Red Deer in Bieszczady National Park

addition to genetic and habitat constraints, antler growth may also be reduced seriously by human-related disturbance (Bobek at al. 1990b). This factor should also be considered and controlled by management.

Another crucial component of wildlife in Bieszczady is the wolf. Studies of the diet of wolves in winter (on the basis of stomach contents) and over the entire year (on the basis of scat analyses) reveal that deer are the most important item (Lesniewicz and Perzanowski 1989, Smietana and Klimek 1993). The old questions regarding the influence of wolves on a deer population were answered by a study of the condition, sex, and age of wolf kills, as were suspicions about the

possibility of wolves killing prime stags at the end of winter. It was proved that even if some stags, exhausted after the rut, do fall prey to wolves by the spring, the frequency of such cases is low, and the majority of animals killed under normal weather conditions were individuals almost depleted of fat reserves (Bobek et al. 1990, Okarma 1991, Bobek et al. 1992d).

The population of brown bears in Bieszczady has grown considerably since the 1960s. The most visible effect is the seasonal increase in bear activity in the spring, when they feed on carrion laid out by hunters as bait for wolves and wild boar. A study of diet shows quite a high percentage of agricultural crops, and the bear may become one of the most important nuisance species in Bieszczady if its numbers continue to grow (Table 2) (Frackowiak 1992, Gula 1992, Bobek et al. 1994). Implementing a program for monitoring and assessing the population is thus absolutely necessary.

Finally, the otter, considered almost extinct a few years ago, was found to be relatively widely distributed across the range. The diet of this species is more than 60% fish, but the species eaten most frequently are small and unimportant from the recreational or economic viewpoints. However, since the trout (Salmo trutta) is the most important item in terms of biomass, otters may potentially compete to some extent for fish with anglers and become a nuisance at fish ponds (Harna 1993).

Since the majority of the area in Bieszczady is either intensively penetrated by people or directly managed and exploited in various ways, relations between wildlife species and human populations are quite important. Wolves and bears occasionally prey on livestock (Table 3). According to the latest findings, the best way to reduce the possibility of such conflicts is to maintain high densities of potential prey in the forest and to continue the harvest of large predators outside protected areas at a stable level (Perzanowski 1992, Bobek et al. 1994).

CONCLUSIONS

High densities of deer are desirable not only for hunters but also from the recreational point of view. This can be achieved if forest management measures are oriented towards improving the habitat for wildlife rather than increasing maximal

TABLE 2 Damages Done by Bears to Livestock and Beehives in the Bieszczady Mountains in the Period 1988-92 (Kwiatkowski 1993)

|

Year |

1988 |

1989 |

1990 |

1991 |

1992 |

|

Item |

|||||

|

Bee-hives |

16 |

90 |

138 |

56 |

27 |

|

Cattle |

11 |

20 |

15 |

4 |

— |

|

Sheep |

79 |

92 |

29 |

69 |

— |

|

Other |

1 |

3 |

2 |

7 |

— |

TABLE 3 The Numbers (A) and the Percentage of Total Number of Sheep Grazing in the Bieszczady Mountains (B) Killed by Wolves in the Period 1988-92 (Lesniak 1993)

|

Years |

1988 |

1989 |

1990 |

1991 |

1992 |

|

A |

295 |

315 |

243 |

296 |

307 |

|

B |

0.36 |

0.30 |

0.32 |

0.49 |

1.06 |

timber yields. Since the size of the average protected area is generally too small to encompass viable populations of large herbivores, let alone large predators, it is absolutely necessary to have a management plan for game species which is coordinated with the State Forest Administration. It is also essential to carry out management of the entire Bieszczady range instead of continuing with today's ineffective and unrealistic attempts to treat protected areas as isolated units. A future approach to the management of large mammals should follow the basic principles of ecology and should thus take the natural trends and requirements of these animals into account.

Finally, there is an unavoidable need to limit to a reasonable level the degree of human interference within the area designed for strict protection. The creation of the Biosphere Reserve in Bieszczady provides at least an opportunity to separate the tasks of wildlife protection and management among the areas belonging to various zones of the Reserve.

REFERENCES

Bobek B., Boyce M.S., Kosobucka M. 1984. Factors Affecting Red Deer (Cervus elaphus) Population Density in Southeastern Poland. J. Appl. Ecology 22, 3: 881-891

Bobek B., Perzanowski K., Zielinski J. 1986. Red Deer Population Census in Mountains: Testing of an Alternative Method. Acta theriol. 31: 423-431.

Bobek B., Perzanowski K., Weiner J. 1990a. Energy Expenditure for Reproduction in Male Red Deer. J. Mamm. 70, 2: 230-232.

Bobek B., Kosobucka M., Krzakiewicz A., Perzanowski K., Wolf R. 1990b. Food, Cover and Human Disturbance as the Factors Influencing Antler Weight in Red Deer (Cervus elaphus L.). Proc. 19th IUGB Congr., Trondheim, 1989: 27-34.

Bobek B., Perzanowski K., Bielak M. 1991. Analysis of Forest Habitats for Successful Roe and Red Deer Management in Central Europe. In: Wildlife Conservation - Present Trends and Perspectives for the 21th Century. N. Maruyama, B. Bobek, Y. Ono, W. Regelin, L. Bartos, P.R. Ratcliffe (eds.). Proc. Int. Symp. on Wildlife Conservation, Tsukuba and Yokohama, 1990: 244pp.

Bobek B., Kosobucka M., Perzanowski K., Rebisz S. 1992a. Seasonal Changes in the Group Size and Sex Ratio in Various Populations of Red Deer in Southern Poland. In: B. Bobek, K.Perzanowski, W. Regelin (eds.). Global Trends in Wildlife Management. Trans. 18th IUGB Congress. Vol.2. Swiat Press. Cracow-Warsaw: 185-192.

Bobek B., Kossak S., Merta D. 1992b. The Effect of Ecotone Length on Quality of Red Deer Habitat in Mountain Forest. Sylwan 6: 51-58. (in Polish with English summary)

Bobek B., Morow K., Perzanowski K., Kosobucka M. 1992c. Red Deer (Cervus elaphus L.) - Its Ecology and Management. Swiat Press, Warsaw: 200pp. (in Polish)

Bobek B., Perzanowski K., Smietana W. 1992d. The Influence of Snow Cover on the Patterns of Selection within Red Deer Population by Wolves in Bieszczady Mountains, Poland. In: B. Bobek, K. Perzanowski, W. Regelin (eds.). Global Trends in Wildlife Management. Trans. 18th IUGB Congress. Vol.2. Swiat Press, Cracow-Warsaw: 341-348.

Bobek B., Perzanowski K., Merta D. 1993. The Workplan for Eastern Carpathians Biosphere Reserve. Msc. presented as a poster at 4th EURO MAB Conference. Zakopane, 1993: 6pp.

Bobek B., Merta D. 1994. The Effects of Ecotones on the Weight of Red Deer Antlers in Southeastern Poland. Proc. 1st Int. Wildlife Manage. Congr. Wildlife Society. San Jose, Costa Rica, 1993. (in print)

Bobek B., Perzanowski K. 1994. Intake and Digestibility of Various Natural Diets by Wolves. J. Wildl. Res. (in print)

Bobek B., Perzanowski K., Kwiatkowski Z., Lesniak A., Seremet B. 1994. The Economic Aspects of Brown Bear and Wolf Predation in Southeastern Poland. Proc. 1st Int. Wildlife Manage. Congr. Wildlife Society. San Jose, Costa Rica, 1993. (in print)

Frackowiak W. 1992. The Seasonal Changes in the Diet Composition of Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) in the Bieszczady Mountains. Ninth International Conference on Bear Research and Management, Grenoble, France. Abstract 3.6.

Frackowiak W., Gula R. 1992. The Autumn and Spring Diet of Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) in the Bieszczady Mountains of Poland. Acta theriol. 37,4: 339-344.

Godawa J. 1989. Age Determination in the Red Deer (Cervus elaphus). Acta theriol. 34, 28: 381-384

Gula R. 1992. The Density and the Age Structure of the Population of Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) in the Bieszczady Mountains, Poland. Ninth International Conference on Bear Research and Management, Grenoble, France. Abstract 2.7.

Gula R., Frackowiak W. 1994. Size and Age Structure of the Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) Population in the Bieszczady Mountains, Poland. J. Wildl. Res. 1: 000-000. (in print)

Harna G. 1993. Diet Composition of the Otter (Lutra lutra) in the Bieszczady Mountains, Southeast Poland. Acta theriol. 38,2: 167-174.

Kabza B. 1994. Biosphere Reserves in Poland: Expectation, Realization and Projection. J. Wildl. Res. 1: 000-000. (in print)

Kadziela M. 1984. The Analysis of Fecundity in Red Deer Hinds. Msc. Jagiellonian University, Krakow. (in Polish).

Kapral M. 1984. Seasonal Dynamics of Body Weight in Red Deer in Southeastern Poland. M.Sc. Thesis. Jagiellonian University, Krakow. (in Polish).

Kasprowicz A. 1992. Estimation of Damage Caused by Red Deer in Fir Plantations and Efficiency of ''Emol" Repellents. Sylwan 11: 19-33. (in Polish with English summary)

Kwiatkowski Z. 1993. The Evaluation of Damages Caused by Brown Bears in Southeastern Poland. M.Sc. Thesis, Jagiellonian University. Krakow, Poland. (in Polish).

Langvatn R. 1977. Social Behavior and Population Structure as a Basis for Censusing Red Deer Population. Proc. 13th IUGB Congr., Atlanta: 77-89.

Lankof 1991. The Diet of Red Deer in Bieszczady Mountains. M.Sc. Thesis, Jagiellonian University, Krakow. (in Polish).

Lesniak A. 1993. The Evaluation of Damages Due to Wolf Predation in Southeastern Poland. M.Sc. Thesis, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland. (in Polish).

Lesniewicz K., Perzanowski K. 1989. The Winter Diet of Wolves in Bieszczady Mountains. Acta theriol. 34,27: 373-380.

Moranda J. 1994. The Evaluation of Ecotone Length in Selected Forest Habitats of Bieszczady. M.Sc. Thesis, Jagiellonian University, Krakow, Poland. (in Polish).

Okarma H., Koteja P. 1987. Basal Metabolic Rate in the Gray Wolf in Poland. J. Wildl. Manage. 51,4: 800-801.

Okarma H. 1984. The Physical Condition of Red Deer Falling Prey to the Wolf and Lynx and Harvested in the Carpathian Mountains. Acta theriol. 29,23: 283-290

Okarma H. 1991. Marrow Fat Content, Sex and Age of Red Deer Killed by Wolves in Winter in the Carpathian Mountains. Holarctic Ecology 14: 169-172.

Perzanowski K., Pucek T., Podyma W. 1986. Browse Supply and its Utilization by Deer in Carpathian Beechwood (Fagetum carpaticum). Acta theriol., 31,8: 107-118.

Perzanowski K. 1992. The Economic Aspects of Wolf Predation in Bieszczady Mountains. Proc. Conf. "Wolf in Europe: Current Status and Prospects" Wildbiologische Gesellschaft, Munchen: 126-129

Pis M. 1986. Debarking of Fir (Abies alba) in Cisna Forest District. M.Sc. Theses, Jagiellonian University, Krakow. (in Polish)

Smietana W., Klimek A. 1993. Diet of Wolves in the Bieszczady Mountains, Poland. Acta theriol. 38,3: 245-251.

Wallis se Vries M.F. 1994. Foraging in a Landscape Mosaic. Cip- Gegevens Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag. 161pp.

OLYMPIC ELK: PARALLELS TO RED DEER MANAGEMENT IN TRANSBOUNDARY PROTECTED AREAS OF CENTRAL EUROPE

David M. Leslie, Jr.

U.S. National Biological Service

INTRODUCTION

Biological diversity in any protected area is affected, in part, by the manner in which populations of large herbivores are managed. Any management activities that influence densities of large herbivore populations, such as harvesting or feeding, will in turn affect qualitative and quantitative aspects of biological diversity in a given area. Those management activities that foster high-density populations of large herbivores are likely to have the greatest impact on biological diversity, although a conclusion that high densities will always reduce diversity is not clearly defensible (Denisiuk et al. 1992). In contrast, the complete absence of large herbivores, or their occurrence at very low densities, may result in a reduction of floral diversity (Happe 1993). Clearly, large herbivores—whether endemic or domestic—have the potential to play a key role in the conservation of biological diversity because of their trophic influence on vegetative composition and structure (Leslie 1983, 1986; Leslie et al. 1984, Happe 1993).

In the United States, large herbivores typically are not managed in national parks (i.e., our highest level of protected areas), which has resulted in high-density populations of a variety of ungulate species. Densities that are apparently in excess of some acceptable carrying capacity (Caughley 1976) have caused considerable debate in the United States for decades (e.g., Houston 1982, Wright 1992). Lack of hunting, the loss of major predators at primeval densities (often they were deliberately extirpated), ill-advised feeding programs that can artificially inflate carrying capacity, and refuging of individuals from altered landscapes or human activities outside a protected area can exacerbate problems associated with high density.

On several occasions during this workshop, the advantages and disadvantages of feeding programs for large wild herbivores, particularly red deer (Cervus elaphus; i.e., elk in North America) and European wisant (Bison bonasus) were discussed. Such programs are common and socially rooted throughout Europe and currently practiced in the transboundary biosphere reserves that were the focus of the workshop; they are uncommon in the United States (but see Boyce 1989, Smith and Robbins 1994). Feeding programs theoretically can be used to enhance winter survival and increase population levels of common game species beyond the existing carrying capacity of local habitats, so as to provide the public with more hunting opportunities. Alternately, feeding programs can be used to improve habitat conditions for and enhance recovery of endangered species such as the European wisant.

The population of Roosevelt elk (C. e. roosevelti) in Olympic National Park (Moorhead 1994) is a North American example of an ungulate population that is unregulated by man. The lack of human-induced regulation of this population and the extirpation of predators, particularly wolves (Canis lupus), have caused ongoing concern over the condition of the forage base and the elk themselves. Both conditions have permitted various elk herds in the Park to persist at high densities for over 60 years (Houston et al. 1978, 1990). Elk in Olympic National Park have not been fed by man. The overview that follows permits a general comparison to red deer management in transboundary protected areas of Central Europe, particularly the comparison of unfed and fed ungulate populations and their subsequent impact on biological diversity.

STUDY AREA

Olympic National Park encompasses 3,600 sq. km of pristine old-growth coniferous temperate rainforest in the center of the Olympic Peninsula, Washington, in the extreme northwestern corner of the United States. Copious rainfall typifies much of the Park, particularly on its western side; for example, precipitation at the Hoh Ranger Station on the west side of the Park averages about 350 cm annually. Most of the precipitation below 600 m is rain, but sporadic and ephemeral snowfall usually occurs each winter below this elevation. Temperatures are mild and reflect the maritime influence of the Pacific Ocean.

Vegetation in old-growth forests on the Olympic Peninsula is very heterogeneous. Dominant overstory species include Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), and Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). Forests of red alder (Alnus rubra) and willow (Salix spp.) occur in valley bottoms near glacial rivers, and big-leaf maple (Acer macrophyllum) stands dominate certain edaphic sites. Fonda (1974) associated forest development with a seral chronosequence along river terraces in valley bottoms and argued that given enough time, each would progress toward a western hemlock climax. Others have concluded that much of the Park is a Sitka spruce-western hemlock disclimax (Franklin 1982), perhaps due in part to herbivory by a high-density collective

population of elk and Columbian black-tailed deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus) (Leslie 1983). Because of the moderate and moist climate, many individual trees have a copious cover of cryptogams and other epiphytes; drapes of mosses about 1 m are common on big-leaf maple branches.

As many as 44 species of mammals have been documented in the Hoh Valley on the western side of Olympic National Park. Elk and black-tailed deer are the most conspicuous herbivores, but slugs (Ariolimax spp.), snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus), and mountain beaver (Aplodontia rufa) no doubt contribute significantly to the overall consumption of the flora, and thus influence biological diversity. Populations of predators in the Park were reduced greatly in the early 1900s, and little is known of their specific ecologies today. Extant predators include cougar (Felis concolor), black bear (Ursus americanus), coyote (Canis latrans), and bobcat (Lynx rufus). Cougar sightings have increased substantially in the Park during the past 10 years, which suggests that their populations are increasing.

HISTORY OF ELK IN OLYMPIC NATIONAL PARK

The 3,600 sq. km at the center of the Olympic Peninsula was set aside as a national monument under the initial jurisdiction of the U.S. Forest Service, primarily to protect populations of Roosevelt elk, which were decreasing at an alarming rate due to unregulated market hunting at the turn of the century (Moorhead 1994). Authority over the area was transferred to the U.S. National Park Service in the 1930s, and it became a national park in 1938. Concern over low numbers of elk helped establish Olympic National Park, originally proposed to be named Elk National Park, but concern over high numbers of elk, now protected with hunting prohibited, has dominated many of the subsequent years of the Park's history.

Happe (1993:9-12) recently provided a historical overview of research on the Roosevelt elk population in Olympic National Park, with specific reference to concern over elk densities. The relationship between elk and deer (referred to as cervids below) densities and the apparent overused condition of the vegetation in the Park have been of perennial concern to Park managers since at least the 1920s. Prior to settlement of the Olympic Peninsula in the late 19th century, cervids were plentiful. Within 10 years of settlement, however, cervid numbers were decimated due to market and subsistence hunting. With protection and deliberate predator extermination, cervid numbers (particularly elk) increased to the point that Park managers were concerned that the population had surpassed the ability of the habitat to support it.

Although thorough censuses of the Park's cervid population were not conducted in the 1920s and 1930s, it is possible (in my opinion, likely) that elk populations in particular exceeded carrying capacity during the period, which led to range or forage deterioration as described in early reports (Bailey 1918, Riley 1918, Murie 1935, Sumner 1938, Schwartz 1943, Schwartz and Mitchell 1945).

During several severe winters in the first third of the 20th century (1915-1916, 1917-1918, and two winters between 1933-1937), large winter kills of elk were reported, which suggested that the population was above carrying capacity and that the forage base had been negatively affected by a high-density cervid population. Population estimates of elk ranged from 5,000 to 8,000 during the period. Notable North American wildlife biologists of the time (e.g., A. Muire) expressed concern that elk were overpopulated in the Park. Interestingly, these were exactly the conditions that have prompted wildlife managers to begin feeding programs elsewhere in the United States, perhaps the most notable being the Jackson Hole elk herd in Wyoming, a population that is still fed in winter today largely because of socio-political rather than resource considerations (Boyce 1989, Smith and Robbins 1994). Feeding programs were never undertaken in Olympic National Park, perhaps because the very low-density human population in the area did not cause much public outcry over winter die-offs.

Because of concerns of overpopulation of elk, the prohibition on hunting in the Park was lifted in 1933, but hunting again ceased after the Park's establishment in 1938 (following legislative mandate, hunting generally is not permitted in national parks in the United States). Little attention was directed toward cervid numbers in the Park until the severe winter of 1949 and the associated large die-off of elk. Once again, park personnel focused on the population densities of elk and their apparent negative effect on forage resources. Newman (1954, 1958) concluded, however, that although (1) densities were high, (2) the potential for large winter kills existed, and (3) the forage base was heavily used, the situation appeared to be self-regulating and "natural," despite the lack of predators.

More recently, studies of elk in Olympic National Park have attempted to quantify the complex relationships between habitat and forage use (Jenkins 1980, 1981, Jenkins and Starkey 1982, 1984; Leslie 1983, 1986; Leslie and Jenkins 1985; Leslie et al. 1984, 1985, 1987; Schroer 1986; Happe et al. 1990; Happe 1993; Schroer et al. 1993) and ultimately test the hypothesis that cervid numbers in the Park are self-regulating around ecological carrying capacity, as determined by a dynamic equilibrium between herbivore numbers and availability of useable plant biomass (Caughley 1976). Herbivores at ecological carrying capacity are by definition at high density, have low reproductive output, increased longevity, and may not be in the best physical condition (i.e., just the opposite of the conditions we hope to see in actively managed game populations or domestic herds—a condition referred by Caughley [1976] as economic carrying capacity). Most of this research supports the notion that the collective cervid population in the Park, which is clearly dominated by Roosevelt elk (Leslie 1983), is at equilibrium with its forage base, as hypothesized by Leslie et al. (1984) and recently supported by Happe (1993).

DISCUSSION AND SUMMARY

Maintenance of large herbivore populations at ecological carrying capacity brings a number of consequences that, on the surface, may appear detrimental to objectives focused on the conservation of biological diversity. For example, numerous biologists working over the years in Olympic National Park have noted the impact of herbivory on the shrub layer; browsing maintains an open, park-like understory in many habitats in Olympic's old-growth forests by restricting growth of common shrub layer species. Several preferred shrubs (e.g., elderberry [Sambucus racemosa], thimbleberry [Rubus parviflorus], and Devil's club [Oplopanax horridum]) only grow out of reach of cervids or in areas of restricted access (e.g., on root wads of fallen trees, in steep ravines, or in areas of intense human activities) (Leslie 1983, Leslie et al. 1984). Similarly, growth of salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis ) and ladyfern (Athyrium filix-femina) is retarded dramatically by cervid herbivory (Happe 1993). Selective consumption of tree seedlings by high-density cervids may have influenced the present species composition of some of Olympic's old-growth forests (Leslie 1986).

Herbivory by high-density cervids in Olympic National Park perhaps has its most important impact on the herbaceous and shrub layers by creating and perpetuating grass-dominated patches in what would otherwise be fern- and shrub-dominated forest understories (Happe 1993). Exclosure studies to exclude cervid grazing and browsing at various locations throughout the Park have shown that the shrub layer of some forest types would be dominated by a near monoculture of salmonberry or ladyfern (Leslie 1983, Happe 1993), obviously resulting in a reduction of floral diversity at that site, due to the shading out of various herbaceous species. Happe (1993) concluded that herbivory in the Park created a "more favorable foraging environment" for cervids than would exist if their densities were low or if they were eliminated (as illustrated by exclosure studies). With regard to floral diversity, Happe (1993) documented increased floral species richness on small spatial scales, and long-term, cervid herbivory enhanced the diversity of plant associations in old-growth forest matrix. Grazing by both endemic and domestic ungulates enhances floral diversity in Karkonosze Biosphere Reserve (F. Krahulec, pers. commun.). Similarly, empirical observations in Polish protected areas indicate that grazed areas support higher floral diversity than ungrazed areas (see Denisiuk et al. 1992).

Alteration of the vegetative structure by high-density herbivores, as described above, likely has a pronounced impact on invertebrate and vertebrate taxa that are dependent on particular plant species and structure for food, shelter, etc. Clearly, complete removal of the shrub layer by herbivores in a forested ecosystem would eliminate, for example, shrub-dependent nesting birds, which may be the case in Bialowieza Biosphere Reserve in Poland (L. Tomialojc, pers. commun.) as a result of red deer and wisant herbivory. Alternately, such herbivory could enhance nesting or feeding opportunities for ground-dwelling species. Unfortunately, such effects have not been quantified or investigated in detail in Olympic National Park,

or in other protected areas to my knowledge. Typically, high rates of herbivory by large ungulates have been viewed as negative or destabilizing, but specific impacts to floral and faunal diversity are obscure or not available.

Clearly, herbivores can have an impact on the biological diversity of localized areas in which they occur, and the nature of that impact will vary depending on their densities. It seems plausible to conclude that if a feeding program had been established in Olympic National Park such that cervid densities were even higher, impacts to the flora would be even greater than those described above. Theoretically, winter feeding of cervids can elevate population levels (by increasing winter survival, normally a period of high mortality [Peek 1986]) beyond the capacity of the habitat to sustain the population at other times of the year, or at least force animals to depend on parts of the forage base not normally used due to low palatability and nutrition (e.g., bark or species of low preference, such as spruce [Picea spp.]). Under such conditions, pernicious impacts to biological diversity—first floral and in turn faunal—would be expected.

Clearly, more research is needed to refine the generalizations briefly outlined above. Much of the early work in Olympic National Park did not directly address the issue of herbivore impacts to biological diversity; one can only speculate from narrative accounts. Even contemporary work in the Park has not been designed with the particular intent to evaluate this timely issue. Similarly, effects of feeding programs in Central Europe to elevate herbivore population levels, or maintain artificially high levels, and the subsequent impact on biological diversity needs to be evaluated in detail. At this time, it is theoretically clear that overt manipulation of herbivore numbers, through programs such as feeding and habitat alterations to benefit a few species, affects our ability to conserve biological diversity. Further investigation is needed to quantify these interrelationships fully and to insure adequate conservation of the biological diversity of transboundary protected areas.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to the U.S. National Park Service for funding my research and that of others in Olympic National Park over the years and to K. J. Jenkins and E. E. Starkey, who continually advise me on technical aspects of elk research in temperate rainforests. My participation in this workshop was made possible by the National Research Council, Office for Central Europe and Eurasia; the Polish Academy of Sciences; and the U.S. National Biological Survey.

REFERENCES

Bailey, V. 1918. Report on Investigation of Elk Herds in the Olympic Mountains, Washington. Unpublished report, Olympic National Park files, Port Angeles, Washington, USA.

Boyce, M. S. 1989. The Jackson Elk Herd: Intensive Management in North America. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England.

Caughley, G. 1976. Wildlife Management and the Dynamics of Ungulate Populations. Pages 183-246. In: T. H. Croaker, editor. Applied Ecology, Volume I. Academic Press, London, England.

Denisiuk, Z., A. Kalemba, T. Zajac, A. Ostrowska, S. Gawlinski, J. Sienkiewicz, and M. Rejman-Czajkowska. 1992. Interactions Between Agriculture and Nature Conservation in Poland. Environmental Research Series 6, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, East European Program, Gland, Switzerland.

Fonda, R. W. 1974. Forest Succession in Relation to River Terrace Development in Olympic National Park, Washington. Ecology 55: 927-942.

Franklin, J. F. 1982. Ecosystem Studies in the Hoh River Drainage, Olympic National Park. Pages 1-8. In: E. E. Starkey, J. F. Franklin, J. W. Matthews, editors. Ecological Research in the Parks of the Pacific Northwest. Forest Research Laboratory, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

Happe, P. J. 1993. Ecological Relationships Between Cervid Herbivory and Understory Vegetation in Old-Growth Sitka Spruce-Western Hemlock Forests in Western Washington. Ph.D. Dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

Happe, P. J., K. J. Jenkins, E. E. Starkey, and S. H. Sharrow. 1990. Nutritional Quality and Tannin Astringency of Browse in Clearcuts and Old-Growth Forests. Journal of Wildlife Management 54: 557-566.

Houston, D. B. 1982. The Northern Yellowstone Elk: Ecology and Management. MacMillan Publishing Company, New York, New York, USA.

Houston, D. B., B. B. Moorhead, and R. W. Olson. 1987. Roosevelt Elk Density in Old-Growth Forests in Olympic National Park. Northwest Science 61: 220-225.

Houston, D. B., E. G. Schreiner, B. B. Moorhead, and K. A. Krueger. 1990. Elk in Olympic National Park: Will They Persist Over Time? Natural Areas Journal 10: 6-11.

Jenkins, K. J. 1980. Home Range and Habitat Use by Roosevelt Elk in Olympic National Park, Washington. M.S. Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

Jenkins, K. J. 1981. Status of Elk Populations and Lowland Habitats in Western Olympic National Park. Unpublished report, Oregon Cooperative Park Studies Unit, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

Jenkins, K. J., and E. E. Starkey. 1982. Social Organization of Roosevelt Elk in an Old-Growth Forest. Journal of Mammalogy 63: 331-334.

Jenkins, K. J., and E. E. Starkey. 1984. Habitat Use by Roosevelt Elk in Unmanaged Forests on the Hoh Valley, Washington. Journal of Wildlife Management 48: 642-626.

Leslie, D. M., Jr. 1983. Nutritional Ecology of Cervids in Old-Growth Forests in Olympic National Park, Washington. Ph.D. Dissertation, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

Leslie, D. M., Jr. 1986. How Animals Shape an Old-Growth Forest. American Forests 92(9): 42-44, 50.

Leslie, D. M., Jr., and K. J. Jenkins. 1985. Rutting Mortality among Male Roosevelt Elk. Journal of Mammalogy 66: 163-164.

Leslie, D. M., Jr., and E. E. Starkey. 1985. Fecal Indices to Dietary Quality of Cervids in Old-Growth Forests. Journal of Wildlife Management 49: 142-146.

Leslie, D. M., Jr., E. E. Starkey, and B. G. Smith. 1987. Forage Acquisition by Sympatric Cervids along an Old-Growth Sere. Journal of Mammalogy 68: 430-434.

Leslie, D. M., Jr., E. E. Starkey, and M. Vavra. 1984. Elk and Deer Diets in Old-Growth Forests in Western Washington. Journal of Wildlife Management 48: 762-775.

Moorhead, B. B. 1994. The Forest Elk: Roosevelt Elk in Olympic National Park. Northwest Interpretive Association, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Murie, O. J. 1935. Wildlife of the Olympics. Unpublished report, Olympic National Park files, Port Angeles, Washington, USA.

Newman, C. C. 1954. Special Report on the Roosevelt Elk of Olympic National Park. Unpublished report, Olympic National Park files, Port Angeles, Washington, USA.

Newman, C. C. 1958. Final Report on the Roosevelt Elk of Olympic National Park. Unpublished report, Olympic National Park files, Port Angeles, Washington, USA.

Peek, J. M. 1986. A Review of Wildlife Management. Prentice Hall Publishers, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA.

Riley, S. 1918. Memorandum to Washington Department of Fish and Game. Unpublished memorandum, Olympic National Park files, Port Angeles, Washington, USA.

Schroer, G. L. 1986. Seasonal Distribution and Movements of Migratory Roosevelt Elk in the Olympic Mountains, Washington. M.S. Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, USA.

Schroer, G. L., K. J. Jenkins, and B. B. Moorhead. 1993. Roosevelt Elk Selection of Temperate Rain Forest Seral Stages in Western Washington. Northwest Science 67: 23-29.

Schwartz, J. E. 1943. Range Conditions and Management of the Roosevelt Elk on the Olympic Peninsula. U.S. Forest Service files, Olympia, Washington, USA.

Schwartz, J. E., and G. E. Mitchell. 1945. The Roosevelt Elk on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington. Journal of Wildlife Management 9: 295-319.

Smith, B. L., and R. L. Robbins. 1994. Migrations and Management of the Jackson Elk Herd. U.S. National Biological Survey Resource Publication 199, Washington, DC, USA.

Sumner, L. 1938. Special Report on Elk in Olympic National Park. Unpublished report, Olympic National Park, Port Angeles, Washington, USA.

Wright, R. G. 1992. Wildlife Research and Management in the National Parks. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, Illinois, USA.

A PROPOSED SYSTEM OF CROSS-BORDER PROTECTED AREAS IN THE EASTERN BORDER REGION OF POLAND

Grzegorz Rakowski

Institute of Environmental Protection

INTRODUCTION

For many years, there has been insufficient investment in the areas along the eastern border of Poland (the ''eastern wall"), and consequently these areas now suffer from depopulation. This condition is also the result of the remoteness of these areas from economic centers and the almost total lack of cross-border traffic and local cross-border trade until 1989. Although it has had an obvious negative impact on the economy, this situation, which has lasted for over 45 years, has contributed to the retention of many relatively little-modified areas of high natural and landscape value. Devoid of industry, these sparsely-populated border regions were only rarely visited by tourists because of strict rules relating to stays and travel within the border zone. Similar areas have been retained on the other side of the border in the states which emerged after the disintegration of the USSR, where until recently the border rules were even more rigorous. A considerable portion of these areas on both sides of the border have lacked proper protection up to now.

The change in the political situation in 1989, and in particular the disintegration of the USSR in 1991, has encouraged a spontaneous and explosive development in the traffic of people and goods at the ever-increasing number of border crossings. Extensive areas near border crossings and along routes leading to them are undergoing systematic and rapid degradation, which poses a serious threat to nature. It is therefore essential that the most valuable border areas be brought under legal protection as quickly as possible. However, for this protection to be fully effective, similar steps also must be taken by Poland's eastern neighbors, who are facing similar problems.

The highly valuable natural and landscape features of border regions could also be a basis for promoting tourism in these areas. Currently, traffic at the Polish border crossings is dominated by visitors from neighboring countries who tend not to be involved in tourism. However, it may be supposed that genuine tourists and

citizens of western European countries will constitute an ever greater part of this traffic. Many tourists in transit may be attracted if border areas are protected and managed properly, if the infrastructure is developed (obviously while ensuring the protection of the most valuable natural features), and if the area is appropriately advertised. The enjoyment of the most valuable and attractive border areas, such as the Romincka, Augustowska, and Bialowieska Forests (Puszczas) or the Bieszczady Mountains, could become the main reason for Polish and foreign guests to visit. The attractiveness of these areas would be enhanced considerably were it possible for tourists to visit the entire area of an integral ecological complex regardless of state borders. Moreover, staking the future on tourism would provide an opportunity for the economic development of border regions in Poland and neighboring countries.

All those aspects are included in the concept of a system of Cross-Border Protected Areas (TOChs, a Polish abbreviation standing for Transgraniczne Obszary Chronione), the principles for which were established in 1992 at the Institute of Environmental Protection in Warsaw and the Institute of Tourism in Warsaw. In the first phase of preparation, data were collected on protected areas, valuable natural features, and the tourist economy of border areas of eastern Poland, Russia's Kaliningrad District, southwestern Lithuania, western Belarus, western Ukraine, and northeastern Slovakia. On the basis of the data, eight areas have been nominated as qualifying for protection as cross-border protected areas (TOCh), and a preliminary scheme has been produced. This plan includes the principles by which TOCh areas would function and by which tourism would develop in them.

CREATION OF CROSS-BORDER PROTECTED AREAS

Following are the main aims of the scheme for the system of Cross-Border Protected Areas (TOCh):

-

Protecting those areas in Poland's eastern border region that are most valuable from the standpoints of nature and landscape;

-

Intensifying cooperation between Poland and her eastern neighbors in environmental protection and tourism; and

-

Developing tourism in border areas, thus furnishing an opportunity for the voivodeships and gminas (provinces and civil parishes) of the "eastern wall" and the border regions of neighboring countries to emerge from economic stagnation.

The main principles of the scheme include:

-

Creating a system of Cross-Border Protected Areas along Poland's eastern border at sites selected as the most valuable in terms of nature and landscape. These areas can and should include currently-existing protected areas: national parks, landscape parks, nature reserves, zapovedniks and zakazniks (nature protection areas in the former USSR referred to as nature reserves), as well as other areas which are environmentally valuable but not yet protected.

-

Developing common nature protection regulations for the neighboring countries and establishing principles of tourist traffic within Cross-Border Protected Areas to allow for the possibility of visits to some areas lying either side of the border (e.g., by means of a special tourist zone or special border crossings for tourists).

-

Designating special zones with a primarily touristic function around, at the edges of, and within these areas (in cooperation with the authorities of neighboring countries), and constructing or enhancing the infrastructure in these areas while preserving valuable natural features.

-

Jointly organizing tourism in these areas (guides, specialist groups, ecotourism) and conducting advertising and promotional campaigns (e.g., by producing brochures, tourist maps, books, press advertisements, and offers for travel agencies).

Following is a proposal on the operating principles and status of Cross-Border Protected Areas:

-

Cross-Border Protected Areas are to be ecological corridors connecting Poland's Extensive System of Protected Areas (WSOCh) with the systems of protected areas of our eastern neighbors. These areas should have a status similar to that of Polish Landscape Parks. Independent of the international status of the protected area, individual parts of a given TOCh should be under the protection of a given state in a form typical of that state, e.g., as national parks, landscape parks, nature reserves, zakazniks, zapovedniks, etc.

-

The parts of a TOCh on the territories of each of the neighboring countries should be composed of designated functional areas. For the Polish parts, the most appropriate form would seem to be a union of gminas (civil parishes). Such gminas making up a TOCh should acquire the status of ecological gminas.

-

In the course of drawing up spatial management plans, several zones of different status must be distinguished within the TOCh:

-

A zone of strict protection, including the areas most valuable for nature: strict reserves and national parks, or parts of them. Economic activity should be completely banned in these areas, and only tourism of a specialized nature should be permitted, such as hikes along

-

-

designated scientific or didactic trails, guided groups of specialists, and visits by individual tourist-naturalists who have obtained suitable permit-passes.

-

A zone of landscape protection, including the areas most valuable in terms of landscape. Forestry management should be permitted in these areas, along with traditional forms of management (agricultural production without fertilizers, health foods, beekeeping, etc.). This zone would be earmarked for qualified tourism, including hiking, boating, bicycling, and skiing, as well as more sedentary forms based on stays in guesthouses or private accommodations.

-

A recreational and economic zone, including the edges of the areas most valuable in terms of nature and landscape, as well as some settlement enclaves in the interior. Various forms of economic activity would be permitted here, provided they are in accord with the principles of sustainable development (harmonious coexistence between human activities and the functioning of nature). Industry and intensive agriculture would be excluded. Sedentary forms of tourism would develop primarily in this zone, with small hotels and lodges, centers for tourist services and information, and tourist equipment rental establishments.

-

The appropriate implementation of the protective aims of individual TOCh areas should be overseen by an international scientific board. Such boards should be composed of scientists from the neighboring countries who know the area and its problems very well, directors of smaller autonomous protected areas (e.g., national parks, landscape parks and zapovedniks) within the TOCh, and environmental protection officials of the local governments.

-

In order to fulfill the assumption that tourism in TOCh areas is to be one of the economic bases sustaining the local population, it would be useful if special tourist bureau-agencies could be created to organize, promote, and advertise ecotourism in the areas of a TOCh on both sides of the border. Among other things, these agencies would handle hotel bookings; organize the rental of private accommodations; develop a network of guesthouses and tourist equipment rental centers; organize services for specialized groups; train guides; publish brochures, maps, guidebooks, and other materials; draw appropriate attention to the region's greatest natural and landscape attractions capable of attracting foreign tourists; and promote concepts of sustainable development and ecotourism among the local population. By regulating the scale of tourist traffic within a TOCh, these agencies would ensure that the number of tourists staying in a given place at a given time would not exceed the maximum permissible number. The income from these bureau-agencies would augment the finances of the union of gminas making up the TOCh areas.

The most important problems associated with the creation of a TOCh are:

-

Differences in nature protection regulations between Poland and neighboring countries;

-

Different forms and systems of protected areas in individual countries, as well as different principles by which they function;

-

Differences in the system of administrative divisions, in the legal status of individual administrative units, and in the rights of local governments;

-

Border crossings within a TOCh and the principles by which they would function, as well as international tourist traffic in these areas;

-

Acceptance by the local population and local government of the idea of the TOCh and of the principles by which such areas function (sustainable development, eco- and agrotourism); and

-

Threats to the valuable natural features of cross-border areas posed by mass traffic in transit, uncontrolled tourist traffic, and the contamination of waters air.

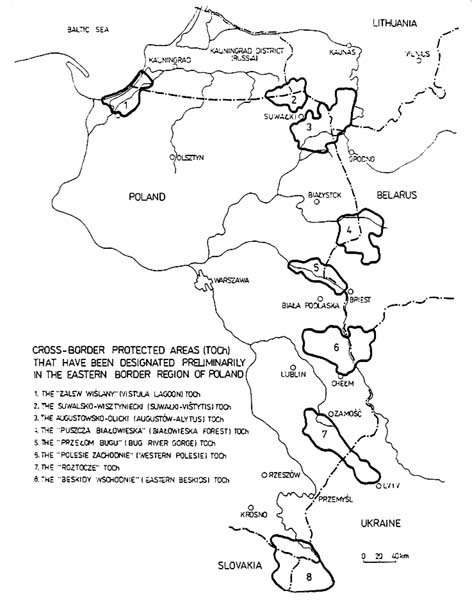

Eight Cross-Border Protected Areas have been preliminarily designated and are shown on the map:

Zalew Wislany (Vistula Lagoon) TOCh

Located on the border between Poland and the Kaliningrad District of Russia, this area will include the Vistula Spit (of which the Polish part is at present a landscape park, while the Russian part is a nature reserve) and almost the entire Vistula Lagoon and its western edges (which includes the Elblag Elevation Landscape Park in the Polish part and the Balga Reserve in the Russian part).

This area has exceptionally favorable conditions for the development of sailing tourism in summer and ice-boating in winter with a large marine basin sheltered from the sea and the proximity of the urban cluster of The Triple City (Gdansk-Gdynia-Sopot), Elblag, and Kaliningrad. There are very good conditions here for sedentary tourism associated with sunbathing and swimming. Almost devoid of people, the Vistula Spit is ideal for ecotourism. Furthermore, the leeward shore of the Vistula Lagoon is characterized by exceptionally valuable landscape as well as by the presence of valuable groupings of historic buildings.

The Suwalsko-Wisztyniecki (Suwalki-Vistytis) TOCh

This area lies on the borders of three countries: Poland, Russia (Kaliningrad District), and Lithuania. On the Polish side, it would comprise the southern part of Puszcza Romincka (the Romincka Forest), as well as Suwalki Landscape Park. On the Russian side, this TOCh would include the northern part of Puszcza Romincka with two areas enjoying landscape protection: the Krasnaya (Bledzianka) River

valley and Lake Vistytis, situated on the border with Lithuania. On the Lithuanian side, this area would encompass Vistytis Regional Park, which is situated east of Lake Vistytis near the border with Poland and Kaliningrad District.

The Romincka Forest area is of outstanding natural value. For several centuries it has been a hunting area famous throughout Europe, a favorite of the rulers of Prussia and later of Germany, and it enjoyed strict protection prior to World War II. The natural and historical value of the Romincka Forest can be compared to that assigned to the Bialowieza Forest, and the opening up of this area for sightseeing and exploration will certainly attract many tourists, especially from Germany. In turn, Suwalski Landscape Park and Vistytis Regional Park in Lithuania are areas of particularly valuable landscape with post-glacial landforms. The attractive landscape and suitable climatic conditions (allowing for winter skiing) create favorable conditions for the development of varied forms of tourism here all year round.

The Augustowsko-Olicki (Augustow-Alytus) TOCh

This area is situated on the borders of three countries: Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus. On the Polish side, it would include Wigierski National Park, as well as Puszcza Augustowska (the Augustow Forest) and parts of the Sejny Lakeland east of Sejny. On the Lithuanian side, this area would encompass the northeastern edge of Puszcza Augustowska, as well as Meteliai and Veisiejai Regional Parks and the adjacent part of the Neman River Valley. On the Belarusian side, this area would include the southeastern edge of Puszcza Augustowska along with Sopockinskij Reserve and part of the adjacent Neman River Valley.

The huge forested area of Puszcza Augustowska combines with lakelands of outstanding landscape value to create perfect conditions for the development of ecotourism. An additional attraction is the prospect of bringing the cross-border section of the Augustow Canal back into use. A European-scale tourist attraction would be created by setting up canoe routes joining the Augustow Lakes, or Lake Wigry, with the Neman River, and by establishing tourist passenger transport from Augustow (Poland) to Grodno (Belarus) or Druskininkai (Lithuania).

In the future, it would be possible to increase the area of the TOCh considerably by adding environmentally valuable areas on the border between Lithuania and Belarus. The TOCh would then include a large, compact area of forest stretching from Augustow almost as far as Vilnius.

The Puszcza Bialowieska (Bialowieska Forest) TOCh

An area straddling the border between Poland and Belarus, this TOCh would embrace the whole of Puszcza Bialowieska, including Belovezhskaya Pushcha National Park and Dikoye Reserve on the Belarus side, as well as Poland's Bialowieski National Park. The creation of an international Polish-Belarusian Biosphere Reserve is also proposed for the whole of the Bialowieska Forest.

The Bialowieska Forest has an established international reputation as an area of outstanding natural value and as a natural refuge of the European bison. The chance to visit both parts of the forest will certainly encourage increase interest in this area and will attract many tourist-naturalists.

The Przelom Bugu (Bug River Gorge) TOCh

This area is situated on the border between Poland and Belarus. It would include the part of the Bug River Valley between Brest and Drohiczyn, as well as adjacent areas on both sides of the border. Plans call for creating a landscape park in the Polish part.

This valuable landscape has a the gorge-like river valley and high morainic hills. This area also has features of sightseeing and cultural interest due to the large number of historic buildings preserved there. In the future, the TOCh should come to encompass the entire border section of the Bug River Valley. It is a phenomenon unique in Europe that the valley of such a large river has a landscape which, as a result of its border location, has changed so little.

The Zachodnie Polesie (Western Polesie) TOCh

Situated on the border between Poland and Ukraine, this area includes on the Polish side Poleski National and Landscape Parks, Leczna Lakeland Landscape Park, Bubnow Marsh Nature Reserve, and Sobiborski, Chelmski, and Strzelecki Landscape Parks. On the Ukrainian side, the area would include Satsk National Park and adjacent areas, as well as the proposed Liubomelskij, Lukivskij, and Pribuzskij Landscape Parks and a fragment of the Bug River Valley forming the national border.

The proposed TOCh is an area of outstanding natural value, protecting the Polesie landscape with its marshes, lakes, forests and numerous sites for rare flora. This landscape is ideal for ecotourism. The area could possibly be enlarged considerably by including large, naturally-valuable marshes on the border between Ukraine and Belarus.

The Roztocze TOCh

This area lies on the border between Poland and Ukraine. On the Polish side, it would embrace Roztoczanski National Park, Szczebrzeszynski Landscape Park, Puszcza Solska Landscape Park, and Krasnobrodzki and Poludniowo-roztoczanski (South Roztocze) Landscape Parks. On the Ukrainian side, it would include Roztocze Zapovednik, the proposed Roztocze National Park, the proposed Potielieckij and Niemirivskij Landscape Parks, and adjacent areas.

Featuring outstanding terrain both in terms of nature and landscape, its attractiveness is increased by the proximity of valuable groups of historic buildings (Zamosc, Zovkva, Lviv), which make it possible for various forms of qualified and sedentary tourism to be enjoyed here.

The Wschodnie Beskidy (Eastern Beskid Mountains) TOCh

This area is located on the borders of Poland, Ukraine, and Slovakia. Included on the Polish side are Bieszczadzki National Park, Cisniansko-Wetlinski Landscape Park, and Dolina Sanu (San River Valley) and Jasliski Landscape Parks. Included on the Slovak side will be the Vychodne Karpaty Protected Area (Chranena Krainna Oblast). Included on the Ukrainian side will be Stuzica Zapovednik, the proposed Skolivski Beskidy National Park, the proposed Orivskij and Sianskij Landscape Parks, and adjacent areas. The central part of the proposed TOCh was brought under protection in 1993 as East Carpathian International Biosphere Reserve.